Abstract

Summary

The aim of this review was to identify factors that influence patients’ adherence to anti-osteoporotic therapy. Factors identified that were associated with poorer medication adherence included polypharmacy, older age, and misconceptions about osteoporosis. Physicians need to be aware of these factors so as to optimize therapeutic outcomes for patients.

Introduction

To identify factors that influence patients’ adherence to anti-osteoporotic therapy.

Methods

A systematic review of literature was performed for articles published up till January 2018 using PubMed®, PsychINFO®, Embase®, and CINAHL®. Peer-reviewed articles which examined factors associated with anti-osteoporotic medication adherence were included. Classes of anti-osteoporotic therapy included bisphosphonates, parathyroid hormone-related analogue, denosumab, selective estrogen receptor modulators, estrogen/progestin therapy, calcitonin, and strontium ranelate. Meta-analyses, case reports/series, and other systematic reviews were excluded. Identified factors were classified using the World Health Organization’s five dimensions of medication adherence (condition, patient, therapy, health-system, and socio-economic domains).

Results

Of 2404 articles reviewed, 124 relevant articles were identified. The prevalence of medication adherence ranged from 12.9 to 95.4%. Twenty-four factors with 139 sub-factors were identified. Bisphosphonates were the most well-studied class of medication (n = 59, 48%). Condition-related factors that were associated with poorer medication adherence included polypharmacy, and history of falls was associated with higher medication adherence. Patient-related factors which were associated with poorer medication adherence included older age and misconceptions about osteoporosis while therapy-related factors included higher dosing frequency and medication side effects. Health system-based factors associated with poorer medication adherence included care under different medical specialties and lack of patient education. Socio-economic-related factors associated with poorer medication adherence included current smoker and lack of medical insurance coverage.

Conclusion

This review identified factors associated with poor medication adherence among osteoporotic patients. To optimize therapeutic outcomes for patients, clinicians need to be aware of the complexity of factors affecting medication adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a prevalent public health problem which afflicts over 54 million adults in the USA [1]. Globally, osteoporosis has been implicated in nine million fractures [2]. With the aging population and increased lifespan, the annual prevalence of osteoporosis-related fractures is expected to increase [3]. Medication adherence refers to the extent to which a person takes their medication as prescribed by their healthcare professional. Non-adherence to anti-osteoporotic therapy has been linked with increased risk of fractures as well as healthcare costs [4]. Importantly, osteoporotic fractures have been associated with increased mortality, morbidity, and healthcare costs. Of note, a Swedish study found that fractures contribute to 0.5 billion Euros in healthcare costs annually [5].

Commonly used classes of anti-osteoporotic treatment include bisphosphonates, parathyroid hormone analogues, denosumab, and selective estrogen receptor modulators. These therapies vary in costs, side effect profiles, dosing frequencies, and routes of administration, which have differing implications on medication adherence [6]. A study by McHorney et al. showed that the presence of symptomatic side effects from oral bisphosphonate therapy was significantly associated with poorer medication adherence [7]. Pertaining to dosing frequency, data from literature has been conflicting. While a study showed that lower frequency of medication dosing was the strongest predictor of adherence to bisphosphonate therapy [8], another study showed no difference in medication adherence rates between weekly and monthly therapy [9]. Adherence to anti-osteoporotic therapy is also affected by other factors such as patients’ beliefs, demographics, and comorbidities [10]. Notably, the perceived lack of benefits from anti-osteoporotic treatment was identified in several studies as a common reason for non-adherence [7, 11, 12].

The multitude of factors that affect medication adherence confounds the ability of healthcare professionals to formulate effective interventions to improve outcomes for patients with osteoporosis. Reviews available in literature have only examined medication adherence rates and related outcomes in selected patient populations or among patients on specific drug therapies [4, 13]. To our best knowledge, there is no review performed which has summarized factors affecting medication adherence among patients with osteoporosis. Hence, the aim of this review is to identify and present factors influencing patients’ adherence to anti-osteoporotic therapy.

Methods

A search of literature was conducted in four online databases which included PubMed®, PsychINFO®, Embase®, and CINAHL®. Keywords utilized for the search included (Osteoporosis OR Osteoporoses OR age-related bone loss) AND (medication OR drug OR treatment OR medicine OR therapeutics OR therapy) AND (adherence OR compliance OR persistence OR non-compliance OR non-adherence) AND (factors OR barriers). In addition, hand-searches of references listed in related articles were performed. The literature review was current as of January 2018 with no restriction of articles’ start date.

Two reviewers (CT Yeam and HCC Tan) performed independent evaluation of the articles for inclusion and discussed where discrepancies occurred. Where discrepancies could not be resolved, further discussion was made with a third independent reviewer (JJB Seng).

The review included full-text, original articles published in English which examined usage of anti-osteoporotic treatment in both male and female patients aged 18 years old or more. Classes of treatment examined included bisphosphonates, parathyroid hormone-related analog, denosumab, selective estrogen receptor modulators, estrogen/progestin therapy, calcitonin, strontium ranelate, and calcium and vitamin D-related supplementation. We excluded meta-analyses, case reports, case series, and other systematic reviews.

Factors related to medication adherence that were identified from articles were grouped into categories as per World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation [14]. The five main categories were, namely, patient-related, therapy-related, condition-related, health system, and socio-economic factors. A human model for treatment adherence in patients with osteoporosis was proposed to aid physicians in better visualizing factors that impacted treatment adherence.

Results

A total of 2404 articles were retrieved from PubMed®, PsychINFO®, Embase®, and CINAHL® as shown in Fig. 1. After excluding 591 duplicated articles, a further 1722 articles were excluded for the following reasons: 1497 articles were irrelevant based on title and abstract; 100 articles were not full papers; 93 articles were meta-analyses, case reports, and systematic reviews; and 32 articles were not in English. After 33 additional articles were identified and added from reference search, a total of 124 articles were included and reviewed. Bisphosphonates were the most well-studied class of medication (n = 59, 48%), and most of the studies were conducted in Europe (n = 51, 41%), North America (n = 42, 34%), and Asia (n = 23, 18%). The prevalence of medication adherence across all studies ranged from 12.9 to 95.4%. Among randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies, the rates of medication adherence in ranged from 37.3 to 67.0%. A total of 24 factors with 139 sub-factors were identified and categorized into five categories based on the WHO’s five dimensions of adherence. The types and number of studies that presented for and against each specific factor were presented below. A pie chart (Fig. 2) was utilized to represent the frequency of sub-factors investigated in the studies included. Patient-related factors (29%) were the most commonly studied domain across all studies, followed by therapy-related domain (27%) and condition-related domain (27%). Details pertaining to the characteristics of included studies are reported in Supplementary Table 1.

Condition-related factors

Table 1 shows condition-related factors which were associated with poorer or better medication adherence. A total of three main factors with 35 sub-factors were identified, which were, namely, “past medical history,” “comorbidities,” and “medical screening for osteoporosis” (Table 1). Common past medical history factors associated with higher medication adherence included history of falls or fractures [9, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 52], while factors associated with poorer medication adherence included receiving concomitant treatment for comorbidities [26, 28, 32, 33, 44, 45, 47,48,49, 59] and having psychiatric conditions such as depression [9, 15, 32, 33, 50, 58]. Osteoporotic screening was also associated with better osteoporotic medication adherence [16, 25, 38, 45, 52, 58, 64, 66].

Patient-related factors

Table 2 shows patient-related factors which were associated with poorer or better medication adherence. Six main factors with 36 sub-factors were identified, which were, namely, “patient demographics,” “physical and mental function,” “menopausal-related,” “disease and treatment related,” “family history,” and “others” (Table 2). Demographic factors associated with poorer medication adherence included having lower education levels [6, 10, 40, 44, 47, 57, 66, 75, 80]. Factors related to physical and mental functions included lower levels of physical activity [44, 86, 87]. Higher age of menopause was shown to be associated with poorer medication adherence [26, 59, 88]. Among factors related to disease and treatment perceptions, misconceptions about osteoporosis [43, 65, 80, 87, 89,90,91,92,93,94,95] and the lack of perceived benefit of therapy [30, 41, 43, 48, 64, 81, 88, 93, 95, 96] were shown to lower medication adherence.

Therapy-related factors

Table 3 shows therapy-related factors which were associated with poorer or better medication adherence. Five therapy-related factors with 31 sub-factors were identified which included “medication dosing regimen,” “medication side effects,” “type of osteoporotic medication,” “other medication-related factors,” and “past osteoporotic medication history.” Regimen factors affecting medication adherence included higher dosing frequency [8, 31, 45, 49, 51, 52, 54, 61, 71, 76, 77, 87, 98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108]. The development of medication-related side effects [7, 23, 28, 44, 48, 59, 64, 65, 88, 89, 91,92,93, 97, 109, 111,112,113,114] was associated with poorer medication adherence.

Health-based system factors

Table 4 shows health system-based factors which were associated with poorer or better medication adherence. A total of seven health system-based factors with 16 sub-factors were identified, namely, “healthcare provider”- and “healthcare facilities”-related factors. Healthcare provider factors associated with poorer medication adherence included care under different medical specialities [16, 19, 22, 26, 34, 60, 116]. In addition, healthcare facility factors associated with poorer medication adherence included poor accessibility to medication [89, 91, 111].

Social-economic factors

Table 5 shows social-economic factors which were associated with poorer or better medication adherence. Three socio-economic factors with 21 sub-factors were elucidated, which were “social,” “economic,” and “lifestyle” factors. Social factors associated with poorer medication adherence included location of residence [6, 28, 44, 58]. Economic factors such as higher treatment costs [53, 67, 91, 92] were associated with poorer medication adherence. Lifestyle factors such as smoking [17, 28, 30, 44, 57, 64, 86, 126, 127] were also found to be associated with poorer medication adherence.

Femur model for medication adherence among osteoporosis patients

Incorporating the five broad categories of factors that affects adherence to anti-osteoporotic medication, a femur model for medication adherence, as depicted in Fig. 3, was proposed to aid clinicians in remembering the factors and applying it in their daily clinical practice.

Discussion

This is a systematic review which has evaluated literature extensively for factors that affect medication adherence among patients with osteoporosis. To our best knowledge, it is also the first review which provided an overview of the types and number of studies that supported or disagreed with the factors investigated.

The rate of anti-osteoporotic medication adherence was found to be highly varied across studies and ranged from 12.9 to 95.4%. Potential reasons for this high variability could be attributed to the differences in the characteristics of patient populations and the tools used for assessing adherence. While real-world medication adherence rates were anticipated to be lower, there appeared to be no significant differences in adherence rates in randomized controlled trials compared to non-randomized studies. Some of the tools used for evaluating medication adherence included patient self-reporting, electronic prescription filling records, and pharmacy clinical records, which have their inherent strengths and limitations. Proportion of days covered (PDC) has been recommended as the “gold standard” calculation method for evaluating medication adherence in long-term therapies [128]. However, this was not assessed in studies included in this review. Future studies should hence consider using this tool to assess medication adherence rates among patients with osteoporosis. More importantly, the heterogeneity observed reflects the complex nature of medication adherence and highlighted the need for identification of pertinent factors affecting medication adherence. This will in turn facilitate the development of targeted interventions to improve medication adherence.

Among condition-related factors, receiving concomitant medication for comorbidities was found to be associated with poorer medication adherence. Managing complex medication dosing regimens and instructions can be challenging for patients prescribed with polypharmacy, and this in turn contributes to poor medication adherence [129]. In the recent years, deprescribing of unnecessary medications has been suggested as an avenue to reduce polypharmacy and improve medication adherence [130]. Physicians should hence consider reviewing the medication lists of patients regularly and withdraw unnecessary medication therapies, so as to improve medication adherence among patients. Additionally, psychiatric disorders such as depression were found to be associated with poor medication adherence among patients with osteoporosis. Similar findings have been observed in studies evaluating medication adherence in patients with other chronic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, and rheumatoid arthritis [131,132,133]. A meta-analysis done by Grenard et al. showed that depressed patients were twice more likely to be non-adherent to their chronic disease medication than patients without depression, which was noted consistently across disease types [133]. Interestingly, there is growing evidence which suggests that depression has an unfavorable effect on bone health, and is associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures [134]. Depression has been shown to increase the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and TNF-α, which in turn leads to higher bone resorption [134]. Furthermore, it has also been shown to stimulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis, contributing to hypercortisolemia and increased bone loss [134]. Given the prevalence of depression among patients with chronic diseases such as osteoporosis and its negative consequences on patients’ health, appropriate screening and treatment of depression might aid in improving medication adherence among patients with osteoporosis.

Among patient-related factors, patients with misconceptions about osteoporosis and lack of perceived benefit of therapy were found to be associated with lower adherence to anti-osteoporotic medications. On a similar vein, the lack of patient education and support from healthcare professionals were associated with poorer medication adherence. Although the usage of phone reminders and targeted education sessions by healthcare professionals have been explored as potential interventions to improve medication adherence, data pertaining to their outcomes has been either conflicting or poor. A randomized controlled study by Cooper et al. showed that reminder phone calls from nurses to educate patients about osteoporosis medication and the importance of medication adherence led to a significant increase in medication adherence rates [119]. However, another randomized controlled trial by Bianchi et al. found that the provision of phone reminders and targeted educational programs for patients was not effective in improving compliance to anti-osteoporotic therapy [135]. A potential reason for the above findings could be due to the differences in anti-osteoporotic dosing regimens and frequency of phone reminders utilized in the two studies. While Cooper et al. utilized monthly phone call reminders for patients on monthly bisphosphonate therapy, the latter study included patients on daily, weekly, and monthly bisphosphonate therapy for which 3-monthly phone reminders were made. Hence, there may remain a potential role of utilizing frequent reminder phone calls to reinforce compliance among patients with poor medication adherence, although more studies should be conducted.

Among the therapy-related factors identified, our review found that higher dosing frequency of anti-osteoporotic medication and adverse side effects were associated with poor adherence among patients. For instance, a study by Goldshtein et al. found that the most common reason cited for discontinuation of oral bisphosphonates was due to gastrointestinal side effects such as heartburn and gastric reflux [81]. Hence, physicians should consider mitigating potentially avoidable side effects before initiation of therapy, by providing patient counseling on how to minimize the side effects of medications or even consider alternative route of drug administration (e.g., bisphosphonates). Additionally, regular evaluation and management of adverse effects associated with anti-osteoporotic medication should be performed by physicians on follow-up visits. A systematic review by Hiligsmann et al. found that simplification of dosing regimens has the most significant impact on improving medication adherence and persistence among patients with osteoporosis [136]. Hence, physicians should also endeavor to simplify medication dosing regimens where appropriate, to improve patients’ adherence to medication.

High treatment cost was one of the main socio-economic factors found to be associated with poorer medication adherence. The financial condition of patients should be assessed by physicians when prescribing anti-osteoporotic medications which are more expensive. For example, the annual cost of teriparatide is US$6700 as compared to alendronate acid which costs US$900 per year [137]. For patients requiring financial assistance, they should be referred to channels such as hospital social services for help where appropriate.

In this review, the five broad categories of medication adherence factors were incorporated in the proposed femur model. Each section of the model represents a domain of factors that clinicians should keep in mind during their daily practice when prescribing anti-osteoporotic medication for patients.

There were several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, while a total of 139 sub-factors were identified, the aggregate magnitude of each factor on medication adherence among patients with osteoporosis was not assessed. This should be explored in future meta-analysis. Additionally, while the search terms and strategy were designed to cover a comprehensive base of literature, the omission of potentially relevant articles could not be ruled out. Steps taken to minimize this included utilizing unrestricted search dates in the databases and hand-searching of references listed in the related articles.

Conclusion

In conclusion, through a systematic review of the literature available, factors which were associated with poorer anti-osteoporotic medication adherence were identified, of which several are potentially modifiable. These findings will aid researchers and clinicians in directing future research efforts to optimize medication adherence and outcomes for patients with osteoporosis. This would be of utmost importance with the aging population worldwide, which would see a rise in the number of patients with osteoporosis.

References

Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S, Dawson-Hughes B (2014) The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res 29(11):2520–2526. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2269

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17(12):1726–1733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4

Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA (1997) World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 7(5):407–413

Mikyas Y, Agodoa I, Yurgin N (2014) A systematic review of osteoporosis medication adherence and osteoporosis-related fracture costs in men. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 12(3):267–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-013-0078-1

Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N, Johnell O, Lidgren L, Ponzer S, Svensson O, Abdon P, Ornstein E, Lunsjo K, Thorngren KG, Sernbo I, Rehnberg C, Jonsson B (2006) Costs and quality of life associated with osteoporosis-related fractures in Sweden. Osteoporos Int 17(5):637–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-0015-8

Hansen C, Pedersen BD, Konradsen H, Abrahamsen B (2013) Anti-osteoporotic therapy in Denmark--predictors and demographics of poor refill compliance and poor persistence. Osteoporos Int 24(7):2079–2097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2221-5

McHorney CA, Schousboe JT, Cline RR, Weiss TW (2007) The impact of osteoporosis medication beliefs and side-effect experiences on non-adherence to oral bisphosphonates. Curr Med Res Opin 23(12):3137–3152. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079907x242890

Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, Altman R (2005) Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin 21(9):1453–1460. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079905x61875

Weycker D, Macarios D, Edelsberg J, Oster G (2006) Compliance with drug therapy for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 17(11):1645–1652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0179-x

Gomes DC, Costa-Paiva L, Farhat FC, Pedro AO, Pinto-Neto AM (2011) Ability to follow anti-reabsorptive drug treatment in postmenopausal women with reduced bone mass. Menopause 18(5):531–536. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181fda7e7

Cook PF, Emiliozzi S, McCabe MM (2007) Telephone counseling to improve osteoporosis treatment adherence: an effectiveness study in community practice settings. Am J Med Qual 22(6):445–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860607307990

Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Lyles K, Saag KG, Delzell E (2008) Benefit of adherence with bisphosphonates depends on age and fracture type: results from an analysis of 101,038 new bisphosphonate users. J Bone Miner Res 23(9):1435–1441. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.080418

Imaz I, Zegarra P, Gonzalez-Enriquez J, Rubio B, Alcazar R, Amate JM (2010) Poor bisphosphonate adherence for treatment of osteoporosis increases fracture risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 21(11):1943–1951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1134-4

Burkhart PV, Sabate E (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. J Nurs Scholarsh 35(3):207

Tasci I, Cintosun U, Safer U, Naharci MI, Bozoglu E, Aydogdu A, Doruk H (2017) Assessment of geriatric predictors of adherence to zoledronic acid treatment for osteoporosis: a prospective follow-up study. Acta Clin Belg:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/17843286.2017.1412863

Yu SF, Yang TS, Chiu WC, Hsu CY, Chou CL, Su YJ, Lai HM, Chen YC, Chen CJ, Cheng TT (2013) Non-adherence to anti-osteoporotic medications in Taiwan: physician specialty makes a difference. J Bone Miner Metab 31(3):351–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-013-0424-2

Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Papaioannou N, Gielen E, Feudjo Tepie M, Toffis C, Frieling I, Geusens P, Makras P, Boschitsch E, Callens J, Anastasilakis AD, Niedhart C, Resch H, Kalouche-Khalil L, Hadji P (2017) Factors associated with high 24-month persistence with denosumab: results of a real-world, non-interventional study of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis in Germany, Austria, Greece, and Belgium. Arch Osteoporos 12(1):58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-017-0351-2

Iwamoto J, Miyata A, Sato Y, Takeda T, Matsumoto H (2009) Factors affecting discontinuation of alendronate treatment in postmenopausal Japanese women with osteoporosis. J Chin Med Assoc 72(12):619–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1726-4901(09)70442-3

Yun H, Curtis JR, Guo L, Kilgore M, Muntner P, Saag K, Matthews R, Morrisey M, Wright NC, Becker DJ, Delzell E (2014) Patterns and predictors of osteoporosis medication discontinuation and switching among Medicare beneficiaries. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15:112. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-112

Roerholt C, Eiken P, Abrahamsen B (2009) Initiation of anti-osteoporotic therapy in patients with recent fractures: a nationwide analysis of prescription rates and persistence. Osteopor Int 20(2):299–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0651-x

Palacios S, Sanchez-Borrego R, Neyro JL, Quereda F, Vazquez F, Perez M, Perez M (2009) Knowledge and compliance from patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis treatment. Menopause Int 15(3):113–119. https://doi.org/10.1258/mi.2009.009029

Hadji P, Papaioannou N, Gielen E, Feudjo Tepie M, Zhang E, Frieling I, Geusens P, Makras P, Resch H, Moller G, Kalouche-Khalil L, Fahrleitner-Pammer A (2015) Persistence, adherence, and medication-taking behavior in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis receiving denosumab in routine practice in Germany, Austria, Greece, and Belgium: 12-month results from a European non-interventional study. Osteoporos Int 26(10):2479–2489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3164-4

Arden NK, Earl S, Fisher DJ, Cooper C, Carruthers S, Goater M (2006) Persistence with teriparatide in patients with osteoporosis: the UK experience. Osteoporos Int 17(11):1626–1629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0171-5

Cheen MH, Kong MC, Zhang RF, Tee FM, Chandran M (2012) Adherence to osteoporosis medications amongst Singaporean patients. Osteoporos Int 23(3):1053–1060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1635-9

Solomon DH, Avorn J, Katz JN, Finkelstein JS, Arnold M, Polinski JM, Brookhart MA (2005) Compliance with osteoporosis medications. Arch Intern Med 165(20):2414–2419. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.20.2414

Rossini M, Bianchi G, Di Munno O, Giannini S, Minisola S, Sinigaglia L, Adami S (2006) Determinants of adherence to osteoporosis treatment in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 17(6):914–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0073-6

Kyvernitakis I, Kostev K, Kurth A, Albert US, Hadji P (2014) Differences in persistency with teriparatide in patients with osteoporosis according to gender and health care provider. Osteoporos Int 25(12):2721–2728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2810-6

Wade SW, Satram-Hoang S, Stolshek BS (2014) Long-term persistence and switching patterns among women using osteoporosis therapies: 24- and 36-month results from POSSIBLE US. Osteoporos Int 25(9):2279–2290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2762-x

Dugard MN, Jones TJ, Davie MW (2010) Uptake of treatment for osteoporosis and compliance after bone density measurement in the community. J Epidemiol Community Health 64(6):518–522. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.084558

Ziller V, Wetzel K, Kyvernitakis I, Seker-Pektas B, Hadji P (2011) Adherence and persistence in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis treated with raloxifene. Climacteric 14(2):228–235. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2010.514628

Penning-van Beest FJ, Erkens JA, Olson M, Herings RM (2008) Determinants of non-compliance with bisphosphonates in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin 24(5):1337–1344. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079908x297358

Modi A, Siris S, Yang X, Fan CP, Sajjan S (2015) Association between gastrointestinal events and persistence with osteoporosis therapy: analysis of administrative claims of a U.S. managed care population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 21(6):499–506. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.6.499

Siris ES, Fan CS, Yang X, Sajjan S, Sen SS, Modi A (2016) Association between gastrointestinal events and compliance with osteoporosis therapy. Bone Rep 4:5–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bonr.2015.10.006

Cheng TT, Yu SF, Hsu CY, Chen SH, Su BY, Yang TS (2013) Differences in adherence to osteoporosis regimens: a 2-year analysis of a population treated under specific guidelines. Clin Ther 35(7):1005–1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.05.019

Papaioannou A, Ioannidis G, Adachi JD, Sebaldt RJ, Ferko N, Puglia M, Brown J, Tenenhouse A, Olszynski WP, Boulos P, Hanley DA, Josse R, Murray TM, Petrie A, Goldsmith CH (2003) Adherence to bisphosphonates and hormone replacement therapy in a tertiary care setting of patients in the CANDOO database. Osteoporos Int 14(10):808–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-003-1431-2

Carr AJ, Thompson PW, Cooper C (2006) Factors associated with adherence and persistence to bisphosphonate therapy in osteoporosis: a cross-sectional survey. Osteoporos Int 17(11):1638–1644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0166-2

Tanaka I, Sato M, Sugihara T, Faries DE, Nojiri S, Graham-Clarke P, Flynn JA, Burge RT (2013) Adherence and persistence with once-daily teriparatide in Japan: a retrospective, prescription database, cohort study. J Osteoporos 2013:654218. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/654218

Lo JC, Pressman AR, Omar MA, Ettinger B (2006) Persistence with weekly alendronate therapy among postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 17(6):922–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0085-2

Abobului M, Berghea F, Vlad V, Balanescu A, Opris D, Bojinca V, Kosevoi Tichie A, Predeteanu D, Ionescu R (2015) Evaluation of adherence to anti-osteoporosis treatment from the socio-economic context. J Med Life 8(Spec Issue):119–123

Roh YH, Koh YD, Noh JH, Gong HS, Baek GH (2017) Effect of health literacy on adherence to osteoporosis treatment among patients with distal radius fracture. Arch Osteoporos 12(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-017-0337-0

Ringe JD, Christodoulakos GE, Mellstrom D, Petto H, Nickelsen T, Marin F, Pavo I (2007) Patient compliance with alendronate, risedronate and raloxifene for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Curr Med Res Opin 23(11):2677–2687. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007x226357

Vestergaard P, Hermann AP, Gram J, Jensen LB, Kolthoff N, Abrahamsen B, Brot C, Eiken P (1997) Improving compliance with hormonal replacement therapy in primary osteoporosis prevention. Maturitas 28(2):137–145

Solomon DH, Brookhart MA, Tsao P, Sundaresan D, Andrade SE, Mazor K, Yood R (2011) Predictors of very low adherence with medications for osteoporosis: towards development of a clinical prediction rule. Osteoporos Int 22(6):1737–1743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1381-4

Tosteson AN, Do TP, Wade SW, Anthony MS, Downs RW (2010) Persistence and switching patterns among women with varied osteoporosis medication histories: 12-month results from POSSIBLE US. Osteoporos Int 21(10):1769–1780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1133-5

Cotte FE, Fardellone P, Mercier F, Gaudin AF, Roux C (2010) Adherence to monthly and weekly oral bisphosphonates in women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 21(1):145–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-0930-1

Garcia-Sempere A, Hurtado I, Sanfelix-Genoves J, Rodriguez-Bernal CL, Gil Orozco R, Peiro S, Sanfelix-Gimeno G (2017) Primary and secondary non-adherence to osteoporotic medications after hip fracture in Spain. The PREV2FO population-based retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 7(1):11784. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10899-6

de Castro Gomes DA, Valadares AL, Pinto-Neto AM, Morais SS, Costa-Paiva L (2012) Ability to follow drug treatment with calcium and vitamin D in postmenopausal women with reduced bone mass. Menopause 19(9):989–994. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318247e86a

Zanchetta JR, Hakim C, Lombas C (2004) Observational study of compliance and continuance rates of raloxifene in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 65(6):470–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.curtheres.2005.01.003

Tandon VR, Sharma S, Mahajan S, Mahajan A, Khajuria V, Gillani Z (2014) First Indian prospective randomized comparative study evaluating adherence and compliance of postmenopausal osteoporotic patients for daily alendronate, weekly risedronate and monthly ibandronate regimens of bisphosphonates. J Midlife Health 5(1):29–33. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-7800.127788

Jacob L, Dreher M, Kostev K, Hadji P (2016) Increased treatment persistence and its determinants in women with osteoporosis with prior fracture compared to those without fracture. Osteoporos Int 27(3):963–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3378-5

Penning-van Beest FJ, Goettsch WG, Erkens JA, Herings RM (2006) Determinants of persistence with bisphosphonates: a study in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Clin Ther 28(2):236–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.01.002

Curtis JR, Xi J, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Lyles K, Saag KG, Delzell E (2009) Improving the prediction of medication compliance: the example of bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Med Care 47(3):334–341. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818afa1c

Weiss TW, Henderson SC, McHorney CA, Cramer JA (2007) Persistence across weekly and monthly bisphosphonates: analysis of US retail pharmacy prescription refills. Curr Med Res Opin 23(9):2193–2203. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079907x226069

Cramer JA, Lynch NO, Gaudin AF, Walker M, Cowell W (2006) The effect of dosing frequency on compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy in postmenopausal women: a comparison of studies in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Clin Ther 28(10):1686–1694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.10.013

Reynolds K, Muntner P, Cheetham TC, Harrison TN, Morisky DE, Silverman S, Gold DT, Vansomphone SS, Wei R, O'Malley CD (2013) Primary non-adherence to bisphosphonates in an integrated healthcare setting. Osteoporos Int 24(9):2509–2517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2326-5

Modi A, Sen S, Adachi JD, Adami S, Cortet B, Cooper AL, Geusens P, Mellstrom D, Weaver JP, van den Bergh JP, Keown P, Sajjan S (2017) The impact of GI events on persistence and adherence to osteoporosis treatment: 3-, 6-, and 12-month findings in the MUSIC-OS study. Osteoporos Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4271-1

Castelo-Branco C, Cortes X, Ferrer M (2010) Treatment persistence and compliance with a combination of calcium and vitamin D. Climacteric 13(6):578–584. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697130903452804

Silverman SL, Siris E, Kendler DL, Belazi D, Brown JP, Gold DT, Lewiecki EM, Papaioannou A, Simonelli C, Ferreira I, Balasubramanian A, Dakin P, Ho P, Siddhanti S, Stolshek B, Recknor C (2015) Persistence at 12 months with denosumab in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: interim results from a prospective observational study. Osteoporos Int 26(1):361–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2871-6

Sanfelix-Genoves J, Gil-Guillen VF, Orozco-Beltran D, Giner-Ruiz V, Pertusa-Martinez S, Reig-Moya B, Carratala C (2009) Determinant factors of osteoporosis patients’ reported therapeutic adherence to calcium and/or vitamin D supplements: a cross-sectional, observational study of postmenopausal women. Drugs Aging 26(10):861–869. https://doi.org/10.2165/11317070-000000000-00000

Chiu CK, Kuo MC, Yu SF, Su BY, Cheng TT (2013) Adherence to osteoporosis regimens among men and analysis of risk factors of poor compliance: a 2-year analytical review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14:276. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-14-276

Park JH, Park EK, Koo DW, Lee S, Lee SH, Kim GT, Lee SG (2017) Compliance and persistence with oral bisphosphonates for the treatment of osteoporosis in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18(1):152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1514-4

Jones TJ, Petrella RJ, Crilly R (2008) Determinants of persistence with weekly bisphosphonates in patients with osteoporosis. J Rheumatol 35(9):1865–1873

Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, Chan KA (2008) Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacotherapy 28(4):437–443. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.28.4.437

Schousboe JT, Dowd BE, Davison ML, Kane RL (2010) Association of medication attitudes with non-persistence and non-compliance with medication to prevent fractures. Osteoporos Int 21(11):1899–1909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1141-5

Wozniak LA, Johnson JA, McAlister FA, Beaupre LA, Bellerose D, Rowe BH, Majumdar SR (2017) Understanding fragility fracture patients' decision-making process regarding bisphosphonate treatment. Osteoporos Int 28(1):219–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3693-5

Richards JS, Cannon GW, Hayden CL, Amdur RL, Lazaro D, Mikuls TR, Reimold AM, Caplan L, Johnson DS, Schwab P, Cherascu BN, Kerr GS (2012) Adherence with bisphosphonate therapy in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 64(12):1864–1870. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21777

Foster SA, Foley KA, Meadows ES, Johnston JA, Wang SS, Pohl GM, Long SR (2011) Adherence and persistence with teriparatide among patients with commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid insurance. Osteoporos Int 22(2):551–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1297-z

Ideguchi H, Ohno S, Takase K, Ueda A, Ishigatsubo Y (2008) Outcomes after switching from one bisphosphonate to another in 146 patients at a single university hospital. Osteoporos Int 19(12):1777–1783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0618-y

Ideguchi H, Ohno S, Hattori H, Ishigatsubo Y (2007) Persistence with bisphosphonate therapy including treatment courses with multiple sequential bisphosphonates in the real world. Osteoporos Int 18(10):1421–1427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0406-0

Klop C, Welsing PM, Elders PJ, Overbeek JA, Souverein PC, Burden AM, van Onzenoort HA, Leufkens HG, Bijlsma JW, de Vries F (2015) Long-term persistence with anti-osteoporosis drugs after fracture. Osteoporos Int 26(6):1831–1840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3084-3

Gold DT, Martin BC, Frytak JR, Amonkar MM, Cosman F (2007) A claims database analysis of persistence with alendronate therapy and fracture risk in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin 23(3):585–594. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079906x167615

Curtis JR, Yun H, Matthews R, Saag KG, Delzell E (2012) Adherence with intravenous zoledronate and intravenous ibandronate in the United States Medicare population. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64(7):1054–1060. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21638

Hui RL, Adams AL, Niu F, Ettinger B, Yi DK, Chandra M, Lo JC (2017) Predicting adherence and persistence with oral bisphosphonate therapy in an integrated health care delivery system. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 23(4):503–512. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.4.503

Segal E, Tamir A, Ish-Shalom S (2003) Compliance of osteoporotic patients with different treatment regimens. Isr Med Assoc J 5(12):859–862

Devold HM, Furu K, Skurtveit S, Tverdal A, Falch JA, Sogaard AJ (2012) Influence of socioeconomic factors on the adherence of alendronate treatment in incident users in Norway. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 21(3):297–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.2344

Confavreux CB, Canoui-Poitrine F, Schott AM, Ambrosi V, Tainturier V, Chapurlat RD (2012) Persistence at 1 year of oral antiosteoporotic drugs: a prospective study in a comprehensive health insurance database. Eur J Endocrinol 166(4):735–741. https://doi.org/10.1530/eje-11-0959

Casula M, Catapano AL, Piccinelli R, Menditto E, Manzoli L, De Fendi L, Orlando V, Flacco ME, Gambera M, Filippi A, Tragni E (2014) Assessment and potential determinants of compliance and persistence to antiosteoporosis therapy in Italy. Am J Manag Care 20(5):e138–e145

van Boven JF, de Boer PT, Postma MJ, Vegter S (2013) Persistence with osteoporosis medication among newly-treated osteoporotic patients. J Bone Miner Metab 31(5):562–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-013-0440-2

Netelenbos JC, Geusens PP, Ypma G, Buijs SJ (2011) Adherence and profile of non-persistence in patients treated for osteoporosis—a large-scale, long-term retrospective study in the Netherlands. Osteoporos Int 22(5):1537–1546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1372-5

Wu X, Wei D, Sun B, Wu XN (2016) Poor medication adherence to bisphosphonates and high self-perception of aging in elderly female patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 27(10):3083–3090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3763-8

Goldshtein I, Rouach V, Shamir-Stein N, Yu J, Chodick G (2016) Role of side effects, physician involvement, and patient perception in non-adherence with oral bisphosphonates. Adv Ther 33(8):1374–1384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0360-3

Lee YK, Nho JH, Ha YC, Koo KH (2012) Persistence with intravenous zoledronate in elderly patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 23(9):2329–2333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1881-x

Sheehy O, Kindundu CM, Barbeau M, LeLorier J (2009) Differences in persistence among different weekly oral bisphosphonate medications. Osteoporos Int 20(8):1369–1376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0795-8

Ganda K, Schaffer A, Pearson S, Seibel MJ (2014) Compliance and persistence to oral bisphosphonate therapy following initiation within a secondary fracture prevention program: a randomised controlled trial of specialist vs. non-specialist management. Osteoporos Int 25(4):1345–1355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2610-4

Thorsteinsson AL, Vestergaard P, Eiken P (2015) Compliance and persistence with treatment with parathyroid hormone for osteoporosis. A Danish national register-based cohort study. Arch Osteoporos 10:35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-015-0237-0

Berecki-Gisolf J, Hockey R, Dobson A (2008) Adherence to bisphosphonate treatment by elderly women. Menopause 15(5):984–990. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31816be98a

Huas D, Debiais F, Blotman F, Cortet B, Mercier F, Rousseaux C, Berger V, Gaudin A-F, Cotté F-E (2010) Compliance and treatment satisfaction of post menopausal women treated for osteoporosis. Compliance with osteoporosis treatment. BMC Womens Health 10:26–26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-10-26

Ziller V, Zimmermann SP, Kalder M, Ziller M, Seker-Pektas B, Hellmeyer L, Hadji P (2010) Adherence and persistence in patients with severe osteoporosis treated with teriparatide. Curr Med Res Opin 26(3):675–681. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990903538409

Kamatari M, Koto S, Ozawa N, Urao C, Suzuki Y, Akasaka E, Yanagimoto K, Sakota K (2007) Factors affecting long-term compliance of osteoporotic patients with bisphosphonate treatment and QOL assessment in actual practice: alendronate and risedronate. J Bone Miner Metab 25(5):302–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-007-0768-6

Nielsen DS, Langdahl BL, Sorensen OH, Sorensen HA, Brixen KT (2010) Persistence to medical treatment of osteoporosis in women at three different clinical settings—a historical cohort study. Scand J Public Health 38(5):502–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810371243

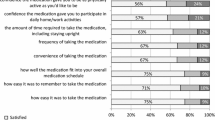

Orimo H, Sato M, Kimura S, Wada K, Chen X, Yoshida S, Crawford B (2017) Understanding the factors associated with initiation and adherence of osteoporosis medication in Japan: an analysis of patient perceptions. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 3(4):174–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afos.2017.10.002

Lindsay BR, Olufade T, Bauer J, Babrowicz J, Hahn R (2016) Patient-reported barriers to osteoporosis therapy. Arch Osteoporos 11:19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-016-0272-5

Salter C, McDaid L, Bhattacharya D, Holland R, Marshall T, Howe A (2014) Abandoned acid? Understanding adherence to bisphosphonate medications for the prevention of osteoporosis among older women: a qualitative longitudinal study. PLoS One 9(1):e83552. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083552

Iversen MD, Vora RR, Servi A, Solomon DH (2011) Factors affecting adherence to osteoporosis medications: a focus group approach examining viewpoints of patients and providers. Journal of geriatric physical therapy (2001) 34(2):72–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPT.0b013e3181ff03b4

Hall SF, Edmonds SW, Lou Y, Cram P, Roblin DW, Saag KG, Wright NC, Jones MP, Wolinsky FD (2017) Patient-reported reasons for nonadherence to recommended osteoporosis pharmacotherapy. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 57(4):503–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2017.05.003

Brask-Lindemann D, Cadarette SM, Eskildsen P, Abrahamsen B (2011) Osteoporosis pharmacotherapy following bone densitometry: importance of patient beliefs and understanding of DXA results. Osteoporos Int 22(5):1493–1501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1365-4

Lewiecki EM, Babbitt AM, Piziak VK, Ozturk ZE, Bone HG (2008) Adherence to and gastrointestinal tolerability of monthly oral or quarterly intravenous ibandronate therapy in women with previous intolerance to oral bisphosphonates: a 12-month, open-label, prospective evaluation. Clin Ther 30(4):605–621

Kertes J, Dushenat M, Vesterman JL, Lemberger J, Bregman J, Friedman N (2008) Factors contributing to compliance with osteoporosis medication. Isr Med Assoc J 10(3):207–213

Blotman F, Cortet B, Hilliquin P, Avouac B, Allaert FA, Pouchain D, Gaudin AF, Cotte FE, El Hasnaoui A (2007) Characterisation of patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis in French primary healthcare. Drugs Aging 24(7):603–614

Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison JJ, Freeman A, Saag KG (2006) Channeling and adherence with alendronate and risedronate among chronic glucocorticoid users. Osteoporos Int 17(8):1268–1274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0136-8

Ettinger B (1998) Alendronate use among 812 women: prevalence of gastrointestinal complaints, noncompliance with patient instructions, and discontinuation. J Manag Care Pharm 4(5):488–492. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.1998.4.5.488

Brankin E, Walker M, Lynch N, Aspray T, Lis Y, Cowell W (2006) The impact of dosing frequency on compliance and persistence with bisphosphonates among postmenopausal women in the UK: evidence from three databases. Curr Med Res Opin 22(7):1249–1256. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079906x112688

Tomkova S, Telepkova D, Vanuga P, Killinger Z, Sulkova I, Celec P, Payer J (2014) Therapeutic adherence to osteoporosis treatment. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 52(8):663–668. https://doi.org/10.5414/cp202072

Recker RR, Gallagher R, MacCosbe PE (2005) Effect of dosing frequency on bisphosphonate medication adherence in a large longitudinal cohort of women. Mayo Clin Proc 80(7):856–861. https://doi.org/10.4065/80.7.856

Downey TW, Foltz SH, Boccuzzi SJ, Omar MA, Kahler KH (2006) Adherence and persistence associated with the pharmacologic treatment of osteoporosis in a managed care setting. South Med J 99(6):570–575. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.smj.0000221637.90495.66

Kishimoto H, Maehara M (2015) Compliance and persistence with daily, weekly, and monthly bisphosphonates for osteoporosis in Japan: analysis of data from the CISA. Arch Osteoporos 10:231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-015-0231-6

Gold DT, Trinh H, Safi W (2009) Weekly versus monthly drug regimens: 1-year compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 25(8):1831–1839. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990903035604

Gold DT, Safi W, Trinh H (2006) Patient preference and adherence: comparative US studies between two bisphosphonates, weekly risedronate and monthly ibandronate. Curr Med Res Opin 22(12):2383–2391. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079906x154042

Hamilton B, McCoy K, Taggart H (2003) Tolerability and compliance with risedronate in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 14(3):259–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-002-1370-3

Lau E, Papaioannou A, Dolovich L, Adachi J, Sawka AM, Burns S, Nair K, Pathak A (2008) Patients’ adherence to osteoporosis therapy: exploring the perceptions of postmenopausal women. Can Fam Physician 54(3):394–402

Pasion EG, Sivananthan SK, Kung AW, Chen SH, Chen YJ, Mirasol R, Tay BK, Shah GA, Khan MA, Tam F, Hall BJ, Thiebaud D (2007) Comparison of raloxifene and bisphosphonates based on adherence and treatment satisfaction in postmenopausal Asian women. J Bone Miner Metab 25(2):105–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-006-0735-7

Conti F, Piscitelli P, Italiano G, Parma A, Caffetti MC, Giolli L, Di Tanna GL, Guazzini A, Brandi ML (2012) Adherence to calcium and vitamin D supplementations: results from the ADVICE survey. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 9(3):157–160

Modi A, Sen S, Adachi JD, Adami S, Cortet B, Cooper AL, Geusens P, Mellstrom D, Weaver J, van den Bergh JP, Nguyen AM, Sajjan S (2016) Gastrointestinal symptoms and association with medication use patterns, adherence, treatment satisfaction, quality of life, and resource use in osteoporosis: baseline results of the MUSIC-OS study. Osteoporos Int 27(3):1227–1238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3388-3

Vytrisalova M, Blazkova S, Palicka V, Vlcek J, Cejkova M, Hala T, Pavelka K, Koblihova H (2008) Self-reported compliance with osteoporosis medication-qualitative aspects and correlates. Maturitas 60(3–4):223–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.07.009

Zarowitz BJ, Cheng LI, Allen C, O'Shea T, Stolshek B (2015) Osteoporosis prevalence and characteristics of treated and untreated nursing home residents with osteoporosis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16(4):341–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.01.073

Turbi C, Herrero-Beaumont G, Acebes JC, Torrijos A, Grana J, Miguelez R, Sacristan J, Marin F (2004) Compliance and satisfaction with raloxifene versus alendronate for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in clinical practice: an open-label, prospective, nonrandomized, observational study. Clin Ther 26(2):245–256

Karlsson L, Lundkvist J, Psachoulia E, Intorcia M, Strom O (2015) Persistence with denosumab and persistence with oral bisphosphonates for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: a retrospective, observational study, and a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 26(10):2401–2411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3253-4

Steel SA, Albertazzi P, Howarth EM, Purdie DW (2003) Factors affecting long-term adherence to hormone replacement therapy after screening for osteoporosis. Climacteric 6(2):96–103

Cooper A, Drake J, Brankin E (2006) Treatment persistence with once-monthly ibandronate and patient support vs. once-weekly alendronate: results from the PERSIST study. Int J Clin Pract 60(8):896–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01059.x

Cheng LI, Durden E, Limone B, Radbill L, Juneau PL, Spangler L, Mirza FM, Stolshek BS (2015) Persistance and compliance with osteroporosis therapies among women in a commercially insured population in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 21(9):824–833, 833a. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.9.824

Strom O, Landfeldt E (2012) The association between automatic generic substitution and treatment persistence with oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporos Int 23(8):2201–2209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1850-4

Ringe JD, Moller G (2009) Differences in persistence, safety and efficacy of generic and original branded once weekly bisphosphonates in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis: 1-year results of a retrospective patient chart review analysis. Rheumatol Int 30(2):213–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-009-0940-5

van der Zwaard BC, van Hout W, Hugtenburg JG, van der Horst HE, Elders PJM (2017) Adherence and persistence of patients using oral bone sparing drugs in primary care. Fam Pract 34(5):525–531. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmw120

Papaioannou A, Khan A, Belanger A, Bensen W, Kendler D, Theoret F, Amin M, Brekke L, Erdmann M, Walker V, Adachi JD (2015) Persistence with denosumab therapy among osteoporotic women in the Canadian patient-support program. Curr Med Res Opin 31(7):1391–1401. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2015.1053049

Shehadeh-Sheeny A, Eilat-Tsanani S, Bishara E, Baron-Epel O (2013) Knowledge and health literacy are not associated with osteoporotic medication adherence, however income is, in Arab postmenopausal women. Patient Educ Couns 93(2):282–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.014

Hansen KE, Swenson ED, Baltz B, Schuna AA, Jones AN, Elliott ME (2008) Adherence to alendronate in male veterans. Osteoporos Int 19(3):349–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0471-4

Clark EM, Gould VC, Tobias JH, Horne R (2016) Natural history, reasons for, and impact of low/non-adherence to medications for osteoporosis in a cohort of community-dwelling older women already established on medication: a 2-year follow-up study. Osteoporos Int 27(2):579–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3271-2

Forbes CA, Deshpande S, Sorio-Vilela F, Kutikova L, Duffy S, Gouni-Berthold I, Hagstrom E (2018) A systematic literature review comparing methods for the measurement of patient persistence and adherence. Curr Med Res Opin:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2018.1477747

Gosch M, Jeske M, Kammerlander C, Roth T (2012) Osteoporosis and polypharmacy. Z Gerontol Geriatr 45(6):450–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-012-0374-7

Reeve E, Wiese MD (2014) Benefits of deprescribing on patients’ adherence to medications. Int J Clin Pharm 36(1):26–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-013-9871-z

Krass I, Schieback P, Dhippayom T (2015) Adherence to diabetes medication: a systematic review. Diabet Med 32(6):725–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12651

DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW (2000) Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med 160(14):2101–2107

Grenard JL, Munjas BA, Adams JL, Suttorp M, Maglione M, McGlynn EA, Gellad WF (2011) Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 26(10):1175–1182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1704-y

Erez HB, Weller A, Vaisman N, Kreitler S (2012) The relationship of depression, anxiety and stress with low bone mineral density in post-menopausal women. Arch Osteoporos 7:247–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-012-0105-0

Bianchi ML, Duca P, Vai S, Guglielmi G, Viti R, Battista C, Scillitani A, Muscarella S, Luisetto G, Camozzi V, Nuti R, Caffarelli C, Gonnelli S, Albanese C, De Tullio V, Isaia G, D'Amelio P, Broggi F, Croci M (2015) Improving adherence to and persistence with oral therapy of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 26(5):1629–1638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3038-9

Hiligsmann M, Salas M, Hughes DA, Manias E, Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Linck P, Cowell W (2013) Interventions to improve osteoporosis medication adherence and persistence: a systematic review and literature appraisal by the ISPOR Medication Adherence & Persistence Special Interest Group. Osteoporos Int 24(12):2907–2918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2364-z

Liu H, Michaud K, Nayak S, Karpf DB, Owens DK, Garber AM (2006) The cost-effectiveness of therapy with teriparatide and alendronate in women with severe osteoporosis. Arch Intern Med 166(11):1209–1217. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.11.1209

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 64 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yeam, C.T., Chia, S., Tan, H.C.C. et al. A systematic review of factors affecting medication adherence among patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 29, 2623–2637 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4759-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4759-3