Abstract

Summary

Our objective was to assess the association of self-reported non-persistence (stopping fracture-prevention medication for more than 1 month) and self-reported non-compliance (missing doses of prescribed medication) with perceived need for fracture-prevention medication, concerns regarding long-term harm from and/or dependence upon medications, and medication-use self-efficacy (confidence in one’s ability to successfully take medication in the context of their daily life).

Introduction

Non-persistence (stopping medication prematurely) and non-compliance (not taking medications at the prescribed times) with oral medications to prevent osteoporotic fractures is widespread and attenuates their fracture reduction benefit.

Methods

Cross-sectional survey and medical record review of 729 patients at a large multispecialty clinic in the United States prescribed an oral bisphosphonate between January 1, 2006 and March 31, 2007.

Results

Low perceived necessity for fracture-prevention medication was strongly associated with non-persistence independent of other predictors, but not with non-compliance. Concerns about medications were associated with non-persistence, but not with non-compliance. Low medication-use self-efficacy was associated with non-persistence and non-compliance.

Conclusions

Non-persistence and non-compliance with oral bisphosphonate medication have different, albeit overlapping, sets of predictors. Low perceived necessity of fracture-prevention medication, high concerns about long-term safety of and dependence upon medication , and low medication-use self-efficacy all predict non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates, whereas low medication-use self-efficacy strongly predicts non-compliance with oral bisphosphonate medication. Assessment of and influence of these medication attitudes among patients at high risk of fracture are likely necessary to achieve better persistence and compliance with fracture-prevention therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fractures related to osteoporosis are a major public health problem. Women and men aged 60 have, respectively, a 44% and 29% chance of experiencing a fracture related to osteoporosis sometime in their remaining lifetime [1]. Medications can reduce fractures by 30% to 50% among those who have osteoporosis by bone density criteria or who already have had a vertebral fracture [2–7]. However, only 30% to 60% of those prescribed a fracture-prevention medication are still taking that medication 1 year later [8, 9]. Medication-use behavior has been conceptualized as having two distinct, albeit overlapping, components; non-persistence with medication, defined as stopping medication prematurely for extended periods of time, and non-compliance, defined as not taking medications at the prescribed times, in the prescribed dose, or prescribed manner [10]. Those at high risk of fracture who do not persist with fracture-prevention medication experience more fractures than those who do persist and comply with those medications [11–15].

Few studies, however, have attempted to explain why those at high risk of fracture do not comply with fracture-prevention medication. Some have postulated that a large proportion of non-persistence and non-compliance with chronic medication are driven by attitudes toward the underlying target disease and the medication proposed to treat it. Horne and colleagues postulate that medication-use behavior is driven by perceptions that specific medications are necessary to maintain or improve their health and by concerns regarding potential overuse of, the long-term safety of, and dependence upon medications [16, 17]. Among patients with heart failure and other cardiac diseases, diabetes mellitus, renal failure, depression, asthma, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome [16, 18, 19], increased perceived necessity for medicines that treat these illnesses is associated with lower non-persistence and non-compliance with these medications. In contrast, increased concerns about the long-term safety of and dependence upon medications are associated with higher medication non-persistence and non-compliance. If this is a valid explanatory framework for medication-use behavior among those prescribed fracture-prevention medication, then improvement of persistence and compliance with fracture-prevention medication may require more detailed assessment of these attitudes than what is typically done during clinical encounters when new medications are prescribed [20].

However, the expectation of a favorable outcome from medication use may be a necessary but insufficient condition for medication persistence and compliance. Belief in one’s ability to carry out a health behavior, or self-efficacy, may also be necessary for that behavior to occur [21–23]. Medication-use self-efficacy, the belief or confidence in one’s ability to successfully take medication in the context of one’s daily life, is associated with medication-use behavior in rheumatoid arthritis [24], HIV infection [25], and hypertension [26].

No study to date has investigated whether the necessity–concerns conceptual framework of Horne and colleagues explains fracture-prevention medication-use behavior among those at high risk of osteoporotic fracture, nor has any study investigated whether or not this framework predicts medication-use behavior independent of other barriers to medication-use and objective indicators of fracture risk. Moreover, no study to date has explored the explanatory power of medication-use behavior of the necessity–concerns framework with medication-use self-efficacy added as an explanatory variable. Finally, no study to date has explored whether attitudes regarding medications have different associations with non-persistence compared to non-compliance. In order to make studies of medication-use behavior more comparable, the medication compliance research community has encouraged standardization of the definitions of medication-use behavior by considering non-persistence and non-compliance separate but related constructs [10].

The primary aim of this study was to assess the association between self-reported non-persistence and non-compliance with oral bisphosphonate therapy and perceived need for fracture-prevention medication, concerns about the long-term safety of and dependence upon medications, and medication-use self-efficacy.

Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both Park Nicollet Heath Services and the University of Minnesota.

This dataset includes a survey and medical record review of patients given one or more prescriptions for oral bisphosphonate therapy, the most common type of oral medication used to prevent fractures related to osteoporosis, at Park Nicollet Clinic between the dates of January 1, 2006 and March 31, 2007. Candidate participants were those aged 21 to 84 with one or more prescriptions for a bisphosphonate medication in the electronic medication record in this time period, who had had a clinic visit within 6 months of the mailing date of the survey (to assure they were still receiving care at Park Nicollet Clinic), and did not have a diagnosis of dementia. All candidate participants had also signed the general Park Nicollet Clinic consent form allowing their medical records to be used for research purposes. Surveys were mailed from July 16 through July 20, 2007 to all 1,179 individuals within the Park Nicollet care system who appeared to meet all inclusion and exclusion criteria. Medical record review subsequently showed that 20 had received either intravenous bisphosphonate medication or subcutaneous teriparatide during the period January 1, 2006 through March 31, 2007, were deceased, had never been prescribed an oral bisphosphonate, or had a diagnosis of dementia.

Dependent variables

Self-reported persistence was assessed with two questions inquiring whether or not respondents had stopped their fracture-prevention medication for more than 1 month due to side effects or for other reasons. Those who answered “yes” to either question were considered non-persistent. Among those with a current prescription for an oral bisphosphonate medication at the time of the survey, non-compliance was defined as missing one or more doses of oral bisphosphonate medication by self-report over the month to receipt of the survey.

Medication attitude predictor variables

For most of the predictor variables that we measured with survey scales, we were unable to find any validated extant measures appropriate for this study and had to develop new scales to measure these. Details of the measurement (psychometric) properties of these scales are provided in the Appendix at the end of this paper.

Perceived need for fracture-prevention medication was assessed by a seven-item scale, adapted for those with osteoporosis and at high risk of fracture, analogous to the disease-specific necessity scales of Horne and colleagues [16]. This scale includes items that assess perceived necessity of bisphosphonate medication to prevent fractures and to preserve one’s health. Concerns about medications was measured by a 11-item scale that assessed patient perceptions regarding the perceived long-term safety of and dependence upon medications, and whether or not medications in their view are over-prescribed. Importantly, this scale does not assess actually experienced side effects (adverse reactions) to any medications. Medication-use self-efficacy was measured with a seven-item scale derived from that of Resnick and colleagues [27], assessing patients’ confidence that they could execute medication-use behavior in the context of their daily lives, even when busy, stressed, away from one’s home, feeling ill, feeling sad, when no one is around to remind them, or when the medication schedule is inconvenient.

Since perceived need for fracture-prevention medication includes items that bisphosphonate medication is needed to preserve one’s health, a high level of concern regarding the long-term safety of bisphosphonates may be associated with the belief that bisphosphonates may not be needed to preserve one’s health. Hence, we postulated that some of the effect of concerns about medication on non-persistence and non-compliance may be indirect, mediated by a negative association with perceived need for fracture-prevention medication (Fig. 1).

Control variables

Family history of hip or spine fracture in parents or siblings, personal history of fracture and perceived medication cost burden were assessed by single survey items.

Additional covariates were assessed by medical record review for all 729 full respondents and for all others (380) who were not deceased, had not actively refused participation, and who had been prescribed injectable fracture-prevention medications between January 1, 2006 and March 31, 2007. We used the number of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) recorded in the medical record as a surrogate marker of prior bad experiences with medications. Importantly, a one-way analysis of variance showed that the number of ADRs in the medical record was not associated with concerns about medications (p value = 0.45). We assessed proton pump inhibitor medication use as a surrogate marker of gastric acidity disorders which predispose to oral bisphosphonate side effects. Smoking status (recorded by nursing staff at clinic visits as current smoker, former smoker, and never a smoker) and oral glucocorticoid use for more than 3 months between January 1, 2006 and March 31, 2007 were recorded because they are objective indicators of increased fracture risk.

Bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine, total hip, femoral neck, and/or the forearm was available in the medical record on all but 43 participants, and was recorded from the bone density test done nearest in time to January 1, 2006. If a lateral spine image was done with the BMD test to document a prevalent vertebral fracture, the presence or absence of one or more prevalent vertebral fractures (which indicate a higher risk of subsequent fracture independent of BMD) documented in the BMD report was recorded.

Statistical analysis

Individuals whose surveys were missing data for one-half or more of the items making up any of the scales were excluded. The remainder of the missing data was filled in using univariate multinomial logit imputation models for each missing item using all other items (including those from other scales and demographic variables) as predictor variables. A posterior distribution for each missing variable was created from these models, and a value for each missing datum was randomly selected from these distributions and imputed into the dataset.

Validation of self-reported non-persistence and non-compliance

Pharmacy claims data for oral bisphosphonate used between January 1, 2006 and March 31, 2007 were available for a small subset of study participants with a current prescription (n = 69). The medication possession ratio (MPR) was calculated as the ratio of the number of days of medication available for use as prescribed between the first and last prescriptions divided by the total number of days between the first and last prescriptions. Non-compliance was defined as an MPR < 0.8, and “compliance” as an MPR ≥ 0.8. Medical record non-persistence was defined as documentation of a bisphosphonate being stopped and the passage of more than one month before a fracture-prevention medication was again prescribed. Agreements of self-reported non-compliance with MPR and of self-reported non-persistence with medical record non-persistence were assessed using kappa statistics.

Regression models

Separate logistic regression models were run with non-persistence and non-compliance as dependent variables. Each model included perceived need for fracture-prevention medication, concerns about medications, and medication-use self-efficacy. We also included the self-reported number of medication doses per day, the number of adverse drug reactions in the medical record, and proton pump inhibitor use (a surrogate marker for gastric acidity disorders) as predictors in the initial models. Control covariates included in the initial models included demographic variables (age, sex, educational attainment, and income level), objective indicators of fracture risk (bone mineral density, personal history of fracture, family history of fracture, prevalent vertebral fracture, smoking status, chronic oral glucocorticoid use), and perceived medication cost burden. For non-persistence, the medication first prescribed during the treatment period was included as a covariate. For non-compliance, the medication still being prescribed at the end of the treatment period was included as a covariate.

C-statistics (areas under receiver operating characteristics [ROC] curves) were calculated to assess the overall explanatory power of the dependent variable for each model without and with the inclusion of the medication attitude predictor variables. The fit of all models was assessed with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test [28]. For each model, Pregibon’s linktest was also used to look for evidence of misspecification of the dependent and predictor variables [29]. To be sure that the non-linear transformation of the perceived medication-need variable did not result in spurious associations with the dependent variables, a second perceived need variable was created by first doubling and then squaring the raw perceived need score, and the models re-run to be sure that the significance of the associations between all predictors and the dependent variables did not change.

For those medication-use-behavior-dependent variables significantly associated with concerns about medication, we tested for mediation of the effects of concerns about medication by perceived need for fracture-prevention medication using the four criteria for mediation of Baron and Kenny [30]. These criteria are (a) that concerns about medication is significantly associated with the mediator (perceived medication need); (b) that the mediator is significantly associated with the dependent variable; (c) that the effect of concerns about medication on the medication-use dependent variable is significant when the mediator is excluded from the set of predictor variables; (d) and that the parameter estimate for the effect of concerns about medication on the medication-use dependent variable significantly changes when the mediator is added to the set of predictor variables. The last of these criteria was tested using the Aroian version of the Sobel test [31–33]. Ordinary least squares was used to test the association of concerns about medication with perceived need for medication, adjusting for objective indicators of fracture risk, age, and educational status.

Secondary analyses were done excluding those on once monthly oral ibandronate at any time during the treatment period, and in subgroups defined by the bone density (worst T-score ≤−2.5 and >−2.5). The statistical significance of differences between the coefficients between these models was evaluated with chi-square tests.

Results

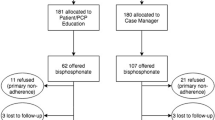

Of the 1,159 eligible participants, 794 returned surveys, four surveys were returned as undeliverable and 50 recipients called back actively refusing participation. Sixty-five respondents were excluded because more than one-half of the items for one or more of the scales measuring predictor variables were not answered. The final response rate was 729 of 1,159, or 62.9%. Among these 729 respondents, 59% sent their survey back by July 31, and 97% had returned their survey by August 31, 2007. Complete data was present for 510 (70%) and for the remaining 219 survey respondents, a mean 1.26 items (of a total of 57) per participant had to be imputed. Six hundred thirty two (86.7%) were first prescribed alendronate, 48 (6.6%) risedronate, and 49 (6.7%) ibandronate. Of the 607 participants still on an oral bisphosphonate medication at the end of the study period, 493 (81.2%) were on alendronate, 68 (11.2%) were on ibandronate, and 46 (7.6%) were on risedronate.

The characteristics of the 729 respondents with useable survey data and 380 non-respondents who did not actively refuse study participation are shown Table 1. Respondents were nearly 2 years older, were slightly more likely to have an active, current prescription for an oral bisphosphonate recorded in the medical record at the time the survey was mailed, had more adverse drug reactions listed in the medical record than non-respondents, and slightly more likely to be a current smoker. Otherwise, non-respondents and respondents were no different with respect to sex, weight, bone mineral density, documentation of prevalent vertebral fracture, use of oral glucocorticoids, or use of proton pump inhibitors.

Non-persistence was reported by 34.2% of the study population; and among the 607 participants with an active prescription for an oral bisphosphonate at the time of the survey, non-compliance was reported by 34.6%. Seventeen percent of compliant individuals had been non-persistent at some point during the prior 18 months compared to 30% of non-compliant individuals (chi2 = 12.8, p value < 0.001). The agreement between non-persistence and medical record documentation of oral bisphosphonate discontinuation was moderate (kappa = 0.47), as was the agreement between non-compliance and medication possession ratio <0.80 (kappa = 0.40).

The patterns of associations of medication attitudes with non-persistence and with non-compliance were different. Self-reported non-persistence was strongly associated with low perceived need for fracture-prevention medication, high concerns about the long-term safety of and dependence upon medications, two or more prior adverse drug reactions, proton pump inhibitor use, and current smoking (Table 2). Low medication-use self-efficacy was strongly associated with non-persistence but its effect was non-linear, with substantial reduction in the odds in non-persistence by improving medication-use self-efficacy from the bottom to second quartile, and no additional effect with further increases in self-efficacy. The c statistic of the model explaining overall non-persistence increased substantially from 0.65 to 0.73 (p value < 0.001) with the addition of perceived medication need and concerns about medication, and increased modestly from 0.73 to 0.76 (p value = 0.016) with the additional inclusion of medication-use self-efficacy. In contrast, non-compliance (missed doses) was not associated with perceived need for fracture-prevention medication or with concerns about medication, but was strongly associated with low medication-use self-efficacy (Table 2). The c statistic of the model explaining non-compliance did not change significantly with the addition of perceived medication need and concerns about medication (p value 0.139), but substantially increased from 0.69 to 0.78 (p value < 0.001) with the inclusion of medication-use self-efficacy in the model.

A one-standard-deviation (SD) increase of concerns about medication were associated with a −0.21 SD change in perceived need for fracture-prevention medication (95% C.I. −0.31 to −0.11). The Sobel test Z-score for mediation of the effect of concerns about medication on non-persistence by perceived need for medication was 1.99 (p value = 0.046), consistent with partial mediation of the effects of concerns about medications on non-persistence by perceived need for medication.

The associations of non-compliance and non-persistence with perceived need for medication, concerns about medication, medication-use self-efficacy (Table 3) and all other predictors were not significantly changed when excluding ibandronate users. However, perceived need for fracture prevention has a significantly stronger association with non-persistence in the subset with a T-score > −2.5 (odds ratio 0.29, 95% C.I.0.18–0.48) compared to the subset with a T-score ≤ −2.5 (odds ratio 0.63, 95% C.I. 0.48 to 0.83; chi2 test that these are equal 7.34, p value = 0.007). All other predictors did not have a significantly different association with non-persistence or non-compliance in those with a T-score > −2.5 compared to those with a T-score ≤ −2.5 (p value = 0.24).

Increases of perceived need for fracture-prevention medication from 1 (SD) below the mean to 1 SD above the mean reduces overall non-persistence by more than half (Table 4). In contrast, the proportion with self-reported non-compliance among those at the highest level of medication-use self-efficacy is one-fifth that of those in the lowest level of medication-use self-efficacy. A change of concerns about medication score from 1 SD above the mean to 1 SD below the mean reduces non-persistence by about 40%.

Independent of these medication attitudes, younger age and higher bone mineral density were associated with self-reported non-compliance, but not with non-persistence. Although current smoking is a risk factor for osteoporotic fracture, current smoking was positively associated with non-persistence. Educational status, self-reported income, sex, the number of prescribed medication doses per day, family or personal history of fracture, and documentation of a prevalent vertebral fracture on VFA were not associated with either non-persistence or non-compliance, independent of medication attitudes or other predictors.

Discussion

Perceived need for medication and concerns about the long-term safety of and dependence on medication are significant predictors of patient-use non-persistence with oral bisphosphonate medication, independent of medication-use self-efficacy and objective indicators of fracture risk. These results are consistent with prior studies of the necessity–concerns framework in groups of patients being treated for hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and HIV. Our results, however, did not confirm the hypotheses that these attitudes are important predictors of self-reported non-compliance.

In contrast, medication-use self-efficacy was a significant predictor of both non-persistence and especially of non-compliance, and its addition to the necessity–concerns framework improves its explanatory power with respect to fracture-prevention-medication use. Self-efficacy and outcome expectations (that execution of a particular behavior will achieve desirable outcomes) are two of the central concepts in self-efficacy (social cognitive) theory and its applications to health behavior [23, 34]. The modified necessity–concerns framework presented in this paper resembles other applications of self-efficacy theory to health behavior in that the belief that a medication is necessary to maintain one’s health implies the expectation of a good outcome from its use, whereas concerns about the long-term safety of and dependence upon medication implies the expectation that bad outcomes may accrue from its use.

Medication-use behavior is multi-faceted, and our results show that non-persistence and non-compliance with oral bisphosphonate medication have different but overlapping sets of predictors, consistent with the conceptualization of these as separate constructs [10]. Clifford and colleagues have shown that perceived necessity and concerns about medications are associated with the intention to take medication, but not with forgetting to take medication [35]. Hence, it is possible that non-persistence is, to a significant degree, an intentional act, a choice more likely to be made if one becomes skeptical of the necessity of the medication or concerned about its long-term safety. Compliance, on the other hand, requires executing medication-use behavior in the context of one’s daily life, and conceivably non-compliance could be intentional or un-intentional. However, we did not measure intentions with respect to medication-use behavior in this study, and these possible explanations for our results will require additional research to be either confirmed or refuted. Nonetheless, based on this study, we believe that the expectation of overall favorable outcomes are necessary for patients to persist with fracture-prevention medication, but that medication-use self-efficacy is necessary to achieve consistent medication use in the context of one’s daily life. Therefore, a higher sense of perceived need for fracture-prevention medication and improved medication-use self-efficacy in particular might significantly reduce incident fractures, whereas reducing concerns about medication may have a more modest effect.

Independent of medication attitudes, bone mineral density was not associated with non-persistence, but for unclear reasons was associated with non-compliance. We believe that objective indicators of fracture risk may influence medication-use behavior indirectly by increasing perceived need for fracture-prevention medication. It is possible that low bone density is associated with other unmeasured confounders (such as a stronger recommendation from the physician and more social support from family members to take fracture-prevention medication) that in turn would reduce non-compliance.

The clinical implications of these results are that improvement of persistence and compliance with medication for those at high risk of fracture may require that physicians, when first prescribing a fracture-prevention medication, solicit and evaluate their patients’ attitudes toward medications, and assure as much as possible that these attitudes are consistent with their objective fracture risk and the known risks and benefits of these medications. However, a recent study has documented that when primary care providers prescribe new medications, they engage in little discussion with their patients regarding critical elements such as the specific need for the medication, how to take it, and potential adverse effects of the medication, let alone the more time-consuming task of engaging the patient in a discussion regarding their attitudes toward the medication and the underlying target condition being treated [20]. Conceivably, this could be addressed either by educating physicians about the importance of and compensating them for the extra time spent in medication counseling or by setting up separate patient-medication decision-making support programs. Further research on the effects of both approaches on medication persistence and compliance is required. Moreover, the cost-effectiveness of such approaches (health benefits gained from more effective medication use compared to the incremental costs for patient decision-making support) is worthy of further study.

Our study has important strengths. The response rate of this study (63%) is equivalent to or better than that reported in most other survey studies of fracture-prevention medication adherence. In contrast to other survey studies of compliance with fracture-prevention medication [36, 37], we had access to participants’ medical records, which allowed us to ascertain additional potential predictor variables (such as bone mineral density and number of adverse medication reactions) of medication-use behavior. Thus, we had a richer phenotypic description of the study population and were better able to compare survey respondents to non-respondents. Ours is the first investigation of the associations of medication attitudes with medication-use behavior to consider non-persistence and non-compliance as separate constructs, and to investigate predictors of non-persistence due to side effects and non-persistence for other reasons separately.

There are important limitations to our study. First, we measured medication-use behavior by self-report, which is only moderately correlated with other measures of medication-use behavior such as pharmacy refill records or electronic pill cap monitoring. However, these other measures of medication use have their own weaknesses [38–43]. For example, possession of medication documented in refill records does not indicate that it was actually taken at the correct time and in the proper manner, and multiple doses may be removed after opening a pill container with an electronic cap once in order to fill a weekly medication organizer. Second, we did not assess comprehensively certain other predictors of medication-use behavior, such as cost of medications (assessed in this study only with a single item as a control covariate). Third, as is true of other survey studies of medication attitudes [37], there is some response bias in our sample in that survey non-responders were less likely to have an active prescription for an oral bisphosphonate in the medical record at the time of the survey, which may indicate a higher rate of non-persistence. However, this is mitigated by the good response to our survey, and the fact that the absolute magnitude of this difference is relatively small. Fourth, our definitions of non-persistence and non-compliance are most appropriate for bisphosphonates taken weekly, and we cannot be certain that our results apply to monthly oral bisphosphonate use. This is strongly mitigated by the fact that our results change little when those prescribed ibandronate are excluded. Finally, ours is a cross-sectional study, and although the associations we have demonstrated in this study are for the most part consistent with our a priori hypotheses of the causality of medication-use behavior, prospective longitudinal studies are necessary to confirm this.

In conclusion, non-persistence and non-compliance with oral bisphosphonates have different but overlapping sets of predictors. Non-persistence with oral bisphosphonate medication to prevent fractures is strongly and negatively associated with perceived need for fracture-prevention medication, positively associated with concerns about medication, and negatively associated with medication-use self-efficacy. In contrast, non-compliance is strongly associated with medication-use self-efficacy, but not with perceived necessity of fracture-prevention medication or concerns about medication. Improvement of persistence and compliance with oral bisphosphonate medication for those at high risk of fracture may require that physicians solicit and evaluate their patients’ attitudes toward medications, and assure as much as possible that these attitudes are consistent with their objective fracture risk and the known risks and benefits of these medications.

References

Nguyen ND, Ahlborg HG, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV (2007) Residual lifetime risk of fractures in women and men. J Bone Miner Res 22:781–788

Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, Bauer DC, Genant HK, Haskell WL, Marcus R, Ott SM, Torner JC, Quandt SA, Reiss TF, Ensrud KE (1996) Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet 348:1535–1541

Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, McKeever CD, Hangartner T, Keller M, Chesnut CH 3rd, Brown J, Eriksen EF, Hoseyni MS, Axelrod DW, Miller PD (1999) Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA 282:1344–1352

McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, Zippel H, Bensen WG, Roux C, Adami S, Fogelman I, Diamond T, Eastell R, Meunier PJ, Reginster JY (2001) Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med 344:333–340

Reginster J, Minne HW, Sorensen OH, Hooper M, Roux C, Brandi ML, Lund B, Ethgen D, Pack S, Roumagnac I, Eastell R (2000) Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. Osteoporos Int 11:83–91

Wells G, Cranney A, Peterson J, Boucher M, Shea B, Robinson V, Coyle D, Tugwell P (2008) Risedronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD004523

MacLean C, Newberry S, Maglione M, McMahon M, Ranganath V, Suttorp M, Mojica W, Timmer M, Alexander A, McNamara M, Desai SB, Zhou A, Chen S, Carter J, Tringale C, Valentine D, Johnsen B, Grossman J (2008) Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of treatments to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med 148:197–213

Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM (2007) A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 18:1023–1031

Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ (2007) Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc 82:1493–1501

Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, Wong PK (2008) Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 11:44–47

Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ (2006) Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone 38:922–928

Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Huybrechts KF, Raggio G, Naujoks C (2004) The impact of compliance with osteoporosis therapy on fracture rates in actual practice. Osteoporos Int 15:1003–1008

Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, Barr CE, Arvesen JN, Abbott TA, Silverman S (2006) Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 81:1013–1022

Rabenda V, Mertens R, Fabri V, Vanoverloop J, Sumkay F, Vannecke C, Deswaef A, Verpooten GA, Reginster JY (2008) Adherence to bisphosphonates therapy and hip fracture risk in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int 19:811–818

Cotte FE, Mercier F, De Pouvourville G (2008) Relationship between compliance and persistence with osteoporosis medications and fracture risk in primary health care in France: a retrospective case-control analysis. Clin Ther 30:2410–2422

Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M (1999) The beliefs about medications questionnaire: the development of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation about medication. Psychol Health 14:1–24

Horne R (1999) Patients' beliefs about treatment: the hidden determinant of treatment outcome? J Psychosom Res 47:491–495

Horne R, Weinman J (2002) Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perception and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health 17:17–32

Horne R, Cooper V, Gellaitry G, Date HL, Fisher M (2007) Patients' perceptions of highly active antiretroviral therapy in relation to treatment uptake and adherence: the utility of the necessity-concerns framework. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 45:334–341

Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, Hays RD, Kravitz RL, Wenger NS (2006) Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch Intern Med 166:1855–1862

Becker MH, Rosenstock IM (1987) Comparing social learning theory and the health belief model. In: Ward WB (ed) Advances in health behavior and promotion. JAI, Greenwich, pp 245–249

O'Leary A (1985) Self-efficacy and health. Behav Res Ther 23:437–451

Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH (1988) Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q 15:175–183

Brus H, van de Laar M, Taal E, Rasker J, Wiegman O (1999) Determinants of compliance with medication in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the importance of self-efficacy expectations. Patient Educ Couns 36:57–64

Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Morin SF, Remien RH, Chesney MA (2007) The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: validation of the HIV treatment adherence self-efficacy scale (HIV-ASES). J Behav Med 30:359–370

Schoenthaler A, Ogedegbe G, Allegrante JP (2009) Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and medication adherence among hypertensive African Americans. Health Educ Behav 36:127–137

Resnick B, Wehren L, Orwig D (2003) Reliability and validity of the self-efficacy and outcome expectations for osteoporosis medication adherence scales. Orthop Nurs 22:139–147

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (2000) Applied logistic regression. Wiley, New York

Pregibon D (1980) Goodness of link tests for generalized linear models. Appl Stat 29:15–24

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Herr NR (2006) Mediation with dichotomous variables. URL: http://nrherr.bol.ucla.edu/Mediation/logmed.html. Accessed on July 15, 2009

MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V (2002) A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods 7:83–104

MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH (1993) Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Eval Rev 17:144–158

Schwarzer R, Fuchs R (1995) Self-efficacy and health behaviors. In: Connor M, Norman P (eds) Predicting health behavior. Open University Press, Philadelphia, pp 163–196

Clifford S, Barber N, Horne R (2008) Understanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional nonadherers, and intentional nonadherers: application of the necessity-concerns framework. J Psychosom Res 64:41–46

Cline RR, Farley JF, Hansen RA, Schommer JC (2005) Osteoporosis beliefs and antiresorptive medication use. Maturitas 50:196–208

McHorney CA, Schousboe JT, Cline RR, Weiss TW (2007) The impact of osteoporosis medication beliefs and side-effect experiences on non-adherence to oral bisphosphonates. Curr Med Res Opin 23:3137–3152

Blumberg EJ, Hovell MF, Kelley NJ, Vera AY, Sipan CL, Berg JP (2005) Self-report INH adherence measures were reliable and valid in Latino adolescents with latent tuberculosis infection. J Clin Epidemiol 58:645–648

Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, Lee ML, Cain E, Cordeiro-Breault M, Canning C, Platt R (1999) Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care 37:846–857

Farmer KC (1999) Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther 21:1074–1090 discussion 1073

Garber MC, Nau DP, Erickson SR, Aikens JE, Lawrence JB (2004) The concordance of self-report with other measures of medication adherence: a summary of the literature. Med Care 42:649–652

Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL, Gibson ES, Bernholz CD, Mukherjee J (1980) Can simple clinical measurements detect patient noncompliance? Hypertension 2:757–764

Mason BJ, Matsuyama JR, Jue SG (1995) Assessment of sulfonylurea adherence and metabolic control. Diabetes Educ 21:52–57

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Park Nicollet Institute and a small unrestricted grant from Proctor and Gamble, Inc.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Schousboe: current research support from Eli Lilly, Inc (2008–2009). Prior consultant work for Roche, Inc., 2008

Dr. Dowd: none

Dr. Davison: none

Dr. Kane: consultant for SCAN Health Plan, United Health Group, and Medtronics

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: psychometric (measurement) properties of survey scales

Appendix: psychometric (measurement) properties of survey scales

All survey items were pre-tested in detail with volunteers with osteoporosis (who were not participants in the main study) to assess whether or not they were clear and interpreted in the way we intended. We randomly split the study sample into two halves, and examined the psychometric properties of the multi-item scales separately in each half. Principal components analysis was done to establish the factor structure of all items within the multi-item scales in both groups. Internal consistency reliability of the multi-item scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, and item-scale correlations were evaluated. The unidimensionality of the summated rating (Likert) scales were established using principal components of each scale separately, and a ratio of the first to second eigenvalue greater than 3.0 was considered to be strong evidence of unidimensionality.

Perceived need for fracture-prevention medication was assessed by a seven-item scale, adapted for those with osteoporosis and at high risk of fracture, analogous to the disease-specific necessity scales of Horne and colleagues [16]. The raw summed scores were squared to achieve a normal distribution. The internal consistency reliability in each half of the study sample, respectively, was 0.87 and 0.86. There was also strong evidence of this being a unidimensional scale, in that principal components analysis showed the ratio of the first to second eigenvalue to be 4.77 and 4.09, respectively, in each half of the study sample. The item-scale correlation ranges were 0.69 to 0.80 and 0.74 to 0.82, respectively, in each half of the study sample.

Concerns about medications was measured by an 11-item scale that assessed patient perceptions regarding the perceived long-term safety of and dependence upon medications, and whether or not medications in their view are over-prescribed. Importantly, this scale does not assess actually experienced side effects (adverse reactions) to any medications. The internal consistency reliability of this scale was 0.85 in both halves of the study sample. The ratio of the first to second eigenvalue was 3.92 and 3.55, respectively, in each half of the study sample. The item-scale correlation ranges were 0.58 to 0.68 and 0.56 to 0.73, respectively, in each half of the study sample.

Medication-use self-efficacy was measured with a seven-item scale derived from that of Resnick and colleagues [27]. In our pre-test, participants expressed difficulty rating their self-efficacy with the original linear rating scale of Resnick and colleagues, and hence we converted this to a Likert scale with five response categories. We also eliminated items in Resnick’s original that referred to side effects or medication costs. We conceived of self-efficacy as confidence in the ability to execute medication-use behavior in the context of one’s daily life and that side effects or concerns about costs may lead one to choose not to take medication but would not influence the confidence to take it should they so choose. Our scale nonetheless had an internal consistency reliability in the two study sample halves, respectively, of 0.94 and 0.93, and was strongly unidimensional (ratio of first to second eigenvalues of 10.58 and 10.38, respectively, in the two study halves). The item-scale correlation ranges were 0.82 to 0.90 and 0.81 to 0.90, respectively, in the two study halves.

Principal components analysis with orthogonal rotation of all three scales together within both study halves showed the loadings of all items onto their hypothesized factor to be 0.51 or higher, and the loadings onto the other two factors to be 0.20 or lower.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schousboe, J.T., Dowd, B.E., Davison, M.L. et al. Association of medication attitudes with non-persistence and non-compliance with medication to prevent fractures. Osteoporos Int 21, 1899–1909 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1141-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1141-5