Abstract

Summary

We estimated primary non-adherence to oral bisphosphonate medication and examined the factors associated with primary non-adherence. Nearly 30 % of women did not pick up their new bisphosphonate within 60 days. Identifying barriers and developing interventions that address patients’ needs and concerns at the time a new medication is prescribed are warranted.

Introduction

To estimate primary non-adherence to oral bisphosphonate medications using electronic medical record data in a large, integrated healthcare delivery system and to describe patient and prescribing provider factors associated with primary non-adherence.

Methods

Women aged 55 years and older enrolled in Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) with a new prescription for oral bisphosphonates between December 1, 2009 and March 31, 2011 were identified. Primary non-adherence was defined as failure to pick up the new prescription within 60 days of the order date. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to investigate patient factors (demographics, healthcare utilization, and health conditions) and prescribing provider characteristics (demographics, years in practice, and specialty) associated with primary non-adherence.

Results

We identified 8,454 eligible women with a new bisphosphonate order. Among these women, 2,497 (29.5 %) did not pick up their bisphosphonate prescription within 60 days of the order date. In multivariable analyses, older age and emergency department utilization were associated with increased odds of primary non-adherence while prescription medication use and hospitalizations were associated with lower odds of primary non-adherence. Prescribing providers practicing 10 or more years had lower odds of primary non-adherent patients compared with providers practicing less than 10 years. Internal medicine and rheumatology providers had lower odds of primary non-adherent patients than primary care providers.

Conclusion

This study found that nearly one in three women failed to pick up their new bisphosphonate prescription within 60 days. Identifying barriers and developing interventions aimed at reducing the number of primary non-adherent patients to bisphosphonate prescriptions are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interventions have been developed to increase medication adherence among patients who have filled their prescriptions; however, if a patient does not possess the medication, initiatives for improvement of secondary adherence will fail. Despite being essential to the characterization of medication adherence, there has been little research on primary non-adherence. Primary non-adherence occurs when a provider orders a medication for a patient and the order is never picked up or dispensed [1].

Historically, primary non-adherence has been difficult to capture, especially in the situation where the patient never takes their prescription to the pharmacy. With the advent of electronic medical records, this type of non-adherence is now easier to identify. However, there are few data on primary non-adherence to osteoporosis therapies. In a systematic review of studies reporting primary non-adherence, Gadkari and McHorney included three studies that reported primary non-adherence to osteoporosis medications [2–5]. Primary non-adherence ranged from 28.4 % to 37.5 % in those studies. However, the estimates were based on relatively small samples from select populations. Additionally, only one of the studies assessed primary non-adherence from administrative pharmacy records [3]. Data from closed-network integrated healthcare delivery systems with electronic medical records may provide the best estimates of primary non-adherence since patients have a financial incentive to pick up prescriptions within the network, which allows more comprehensive capture of prescription fills and more accurate calculations of primary non-adherence [2, 6].

Efforts to understand and improve primary adherence to bisphosphonate therapy, the most commonly prescribed therapy for treatment of osteoporosis, are essential to improving overall adherence. Using electronic medical record data from a large, integrated healthcare delivery system, we estimated primary non-adherence to oral bisphosphonates and examined patient and prescribing provider factors associated with primary non-adherence.

Methods

Setting and study population

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC). KPSC provides comprehensive care for approximately 3.5 million members. The population is diverse and highly representative of the region [7]. Data on the medical care patients receive are captured through structured administrative and clinical databases and an electronic medical record.

The study cohort included women aged 55 years or older who were KPSC members with a new order for a daily or weekly oral bisphosphonate medication between December 1, 2009 and March 31, 2011. We restricted the study to women prescribed daily or weekly bisphosphonate regimens as other dosing schedules are uncommon at KPSC. Women were eligible for inclusion if they were continuously enrolled in the health plan and had a drug benefit for 365 days prior to the initial oral bisphosphonate order in this time period. Women with a prior order for an oral bisphosphonate within 365 days of the initial bisphosphonate order date in the study period were considered prevalent users and excluded from all analyses as were women with a paper prescription. Women with a diagnosis of cancer, Paget’s disease, osteogenesis imperfecta or osteomalacia based on two or more outpatient or one or more inpatient ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification) diagnosis codes in the 12 months prior to the bisphosphonate order were also excluded.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the KPSC Institutional Review Board. Compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations was ensured.

Medication orders

Prescription orders are placed and routed electronically to the KPSC pharmacy information management system (PIMS). Prescriptions sold through KPSC pharmacies are linked with electronic medical record orders through an established electronic interface allowing for the identification of those patients who had a prescription order but never picked it up. The system also captures cancelled orders and paper prescriptions. Paper prescriptions and cancelled orders were identified and excluded. Only electronic orders intended to be dispensed at a KPSC pharmacy were included as we were not able to determine whether paper prescriptions were picked up at a non-KPSC pharmacy.

Patient and prescriber characteristics

Based on published adherence literature, we extracted information from the electronic medical records and administrative databases including patient demographics (age and race/ethnicity), socioeconomic status (geocoded median household family income), a diagnosis of osteoporosis based on one or more outpatient ICD-9 diagnosis codes within 12 months prior to and 6 months after the bisphosphonate order date and a diagnosis of a fragility fracture (hip, distal radius/ulna, spine, humerus, pelvis, and other femur) based on one or more outpatient or inpatient ICD-9 codes in the absence of a concurrent major trauma code and depression based on two or more outpatient or one inpatient ICD-9 diagnosis code within 12 months prior to the bisphosphonate order date (see Appendix 1 for specific ICD-9 codes). Information on healthcare utilization in the 12 months prior to the order date included the number of unique prescription medications obtained (based on the generic product identifier subclass), the number of office visits, and the numbers of emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions. The Deyo adaption of the Charlson Comorbidity Index was determined using ICD-9 diagnosis codes from inpatient and outpatient encounters as an overall measure of disease burden [8]. Ordering prescriber demographics (age and gender), specialty and years practicing at KPSC were also identified to determine if specific provider characteristics were associated with primary non-adherence.

Statistical analysis

The main outcome of primary non-adherence was defined as the patient not picking-up their new bisphosphonate prescription at a KPSC pharmacy within 60 days of the order date. Descriptive statistics were used to compare primary non-adherent patients to those who were adherent to their new bisphosphonate prescription. Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables and percentages were used for categorical variables. Differences in characteristics were assessed using t-tests for continuous variables and χ 2 tests for categorical variables.

Patient and prescribing physician characteristics independently associated with the likelihood of primary non-adherence were investigated using multivariable logistic regression modeling. Variables permitted to enter the model were required to have bivariate p values less than 0.25 [9]. Age and a diagnosis of osteoporosis were considered clinically important and were included in the model regardless of the statistical association with primary non-adherence.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to exclude participants with less than 3 months of continuous enrollment after the bisphosphonate order and by varying the 60-day definition of primary non-adherence to 30 and 90 days. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Study participants

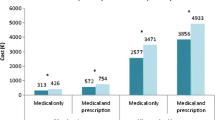

During the study period, 26,508 women received a prescription for a daily or weekly oral bisphosphonate. The majority of women were excluded from the final study cohort because they either did not have 12 months of continuous membership prior to the bisphosphonate order or they had received a bisphosphonate order in the prior 12 months (Fig. 1). Of the 8,454 women who met the inclusion criteria, primary non-adherence was observed among 2,497 (29.5 %) patients. Among the 5,957 women who picked up their prescription, 18.4 % did so on the first day, 64.3 % did so within 7 days and 81.1 % within 14 days of the order date (Fig. 2).

The characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1 stratified by primary adherence status. Compared with women who picked up their new bisphosphonate prescription (primary adherent women), primary non-adherent women were taking fewer prescription medications, were less likely to have a diagnosis of depression, had fewer comorbidities based on their Charlson Comorbidity Index score, and had lower hospitalizations and other healthcare utilization (hospice visits, home health, skilled nursing facility and non-hospital visits) in the prior 12 months. There were no statistically significant differences in mean age, median household family income, diagnosis of osteoporosis, or a history of fragility fracture between adherent and primary non-adherent women.

The characteristics of the prescribing providers are presented in Table 2. Primary non-adherent women were more likely to have their prescription written by a primary care provider compared with adherent women and less likely to have their prescription written by providers in endocrinology, internal medicine or rheumatology. On average, the prescribing providers of primary non-adherent women had been practicing for fewer years at KPSC than prescribing providers of adherent women. There were no statistically significant differences in the gender or mean age of the prescribing provider between the primary adherent and non-adherent women.

In unadjusted models (Table 3), a higher number of prior prescription medications filled, depression diagnosis, a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, hospitalizations, and other healthcare utilization (hospice visits, home health, skilled nursing facility and non-hospital visits) were associated with a lower odds ratio of primary non-adherence. In adjusted models, older age and ED utilization in the prior 12 months were associated with an increased odds ratio of primary non-adherence while prior prescription medication use and hospitalizations were associated with a lower odds ratio of primary non-adherence. In unadjusted models, bisphosphonate prescriptions written by a provider in internal medicine or rheumatology were associated with a lower odds ratio of primary non-adherence than those written by a provider in primary care. Prescribing providers with 10 or more years of practice at KPSC were also less likely to have primary non-adherent patients. Provider characteristics associated with bisphosphonate primary non-adherence were similar after multivariable adjustment.

Results were unchanged after excluding 165 patients (52 in the primary non-adherent group and 113 in the adherent group) who did not have 3 months of continuous enrollment in the health plan following their bisphosphonate order date. Results were also consistent in sensitivity analyses that varied the 60-day definition of primary non-adherence to 30 and 90 days. Defining primary non-adherence as not picking up a bisphosphonate order at 30 days, rather than the 60-day period used in the main analysis, resulted in an increase in the primary non-adherence rate from 29.5 % to 34.4 %. Allowing 90 days for the bisphosphonate to be picked up resulted in a primary non-adherence rate of 27.4 % (data not shown).

Discussion

In the current study of women newly prescribed a daily or weekly oral bisphosphonate in a large, integrated healthcare delivery system, 29.5 % did not pick up their prescription within 60 days after the order date and were considered primary non-adherent. Varying the definition to 30 days and 90 days resulted in primary non-adherence rates of 34.4 % and 27.4 %, respectively. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have reported primary non-adherence to prescription medications for treatment of osteoporosis [3–5, 10]. However, caution should be observed when making comparisons of the findings in our study to corresponding data from previous studies due to differences in study populations and definitions of primary non-adherence. Additionally, the majority of the previous studies were conducted in relatively small samples of selected patient groups and two of the studies relied on patient self-report to capture adherence. In a recent study of antiosteoporosis medications including all calcium regulators and hormone receptor modulators, Shin and colleagues [10] reported a primary non-adherence rate of 22.4 % at 14 days. Waalen and colleagues [3] reported a 28.4 % primary non-adherence rate at 12 months in 102 women aged 60 years and older who were newly diagnosed with osteoporosis and assigned to the usual care group of a randomized trial of a telephone-based intervention. Similarly, Cook and colleagues [4] evaluated a telehealth program delivered to 402 participants who received a new bisphosphonate prescription. Primary non-adherence in that study was 31.0 % at 4 months. Greenwald and colleagues [5] surveyed 144 post-menopausal women aged 49 to 89 years with no prior treatment for osteoporosis and found a primary non-adherence rate of 37.5 % at 30 days.

Few studies have examined factors associated with primary non-adherence [11–14]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine both patient and physician characteristics associated with primary non-adherence to bisphosphonates in the same population. We found that women who were older and had prior ED visits were more likely to be primary non-adherent while women who had prior hospitalizations were less likely to be primary non-adherent. As found in other primary non-adherence studies [10, 15], women in our study who had prior prescriptions filled were also less likely to be primary non-adherent suggesting that these women are willing and comfortable with taking medication. Compared with primary care prescribers, bisphosphonate prescriptions written by internal medicine and rheumatology prescribers were more likely to be picked up as were bisphosphonate prescriptions written by providers with 10 or more years of practice at KPSC compared with providers with less experience at KPSC. These findings may indicate that the quality of the patient–provider relationship influences the patients’ decisions about filling prescriptions. Future research should explore the patient–healthcare provider relationship to determine if this is an important factor in primary non-adherence to bisphosphonate medication.

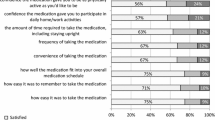

Historically, primary non-adherence has been difficult to measure because it requires the capture of the order and the dispensation of the medication. The increasing use of electronic prescribing will potentially allow healthcare providers to rapidly identify patients who do not fill an initial prescription and intervene on these patients. Although a number of interventions have been conducted to reduce secondary non-adherence to medications [16], there have been few interventions to reduce primary non-adherence. In a recent study, Derose and colleagues [17] demonstrated a modest increase in primary medication adherence to statins with the use of a relatively simple, automated intervention that included a telephone reminder call followed by a letter. Interventions to reduce primary non-adherence will likely be most effective if targeted towards those who are least likely to fill their prescription. Previous studies have indicated that women may perceive osteoporosis to be less of a serious health condition compared to other conditions and they do not perceive themselves to be risk for osteoporosis; both of these factors may lead to primary non-adherence [18–20]. Other commonly cited reasons for failing to initiate bisphosphonate therapy include fear of side effects, the difficult dosing regimen, and a generic distrust of all medications [20–23]. Results from these studies suggest that interventions aimed at reducing primary non-adherence to bisphosphonates should address the patients’ perceived lack of need for the medication and their medication concerns.

There are several limitations to our study that should be considered. The current study was limited to electronic medical record data from a single health plan where the majority of patients have a drug benefit. Therefore, one major barrier to medication adherence, cost, has been essentially eliminated. As such, our findings may not be generalizable to other populations, such as uninsured women. However, the KPSC population has been shown to be generalizable to the Southern California population. The extremely poor and highly educated were only marginally underrepresented among KPSC members in 2010 compared with the general population living in Southern California [7]. This study was limited to daily or weekly oral bisphosphonates and thus the results may not be generalizable to other therapeutic classes or dosing schedules. No direct contact was made with patients to determine their perception of the severity of their disease or the effectiveness of their prescribed therapy or other individual-level experiences and beliefs that may influence primary non-adherence. Additionally, some patients may have been misclassified as non-adherent if they picked up their prescription at a non-KPSC pharmacy, which would not be captured in our databases. However, more than 95 % of KPSC members have a drug benefit providing a strong financial incentive to use only KP pharmacies as KPSC benefits are not honored at non-KP pharmacies. Additionally, to diminish the possibility of this bias, we excluded patients without a KPSC drug benefit. Finally, we did not assess whether patients received any adherence counseling through an outreach program which may have influenced their decision to pick up their new bisphosphonate prescription.

This study has many strengths. One of the strengths of this study was our ability to capture all prescription transactions between the electronic medical record and the dispensing pharmacy. Thus, we were able to exclude prescriptions that were printed and provided to a patient (5.3 % of the oral bisphosphonate prescriptions during the study period), which limits the possibility that prescriptions were provided to non-KPSC pharmacies. Additional strengths of this study include the relatively large and racially diverse population of woman prescribed a new bisphosphonate order and the comprehensive clinical data and information on patient and physician characteristics that are not available in adherence studies limited to claims data. Lastly, patients can receive free medication samples in some healthcare settings. Patients then may opt to try the free samples before filling a new prescription and the dosing regimen and/or perceived side effects may impact whether or not the prescription is picked up. However, KPSC providers are not permitted to receive or provide patients with free samples; therefore, our estimates of primary non-adherence to bisphosphonates would not be affected by such a situation.

Bisphosphonates are the most commonly prescribed therapy for the treatment of osteoporosis. Low adherence to bisphosphonates is common and contributes to increased fracture risk and increased healthcare costs [24]. Therefore, it is essential for healthcare providers to identify patients with sub-optimal adherence so that individualized strategies to improve adherence can be implemented. Efforts have traditionally focused on improving adherence in ongoing users which potentially misses large numbers of patients who receive a prescription but never initiate therapy. In the current study, 29.5 % of women did not pick up their new bisphosphonate prescription within 60 days of the order being placed. Identifying barriers and developing interventions that address the patients’ perceived needs and concerns at the time a new medication is prescribed are warranted to reduce primary non-adherence to bisphosphonates.

References

Beardon PH, McGilchrist MM, McKendrick AD, McDevitt DG, MacDonald TM (1993) Primary non-compliance with prescribed medication in primary care. Bmj 307:846–848

Gadkari AS, McHorney CA (2010) Medication nonfulfillment rates and reasons: narrative systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin 26:683–705. doi:10.1185/03007990903550586

Waalen J, Bruning AL, Peters MJ, Blau EM (2009) A telephone-based intervention for increasing the use of osteoporosis medication: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Manag Care 15:e60–70

Cook PF, Emiliozzi S, McCabe MM (2007) Telephone counseling to improve osteoporosis treatment adherence: an effectiveness study in community practice settings. Am J Med Qual 22:445–456. doi:10.1177/1062860607307990

Greenwald B, Bardwell A, Malinak J, Rude R, Silverman SL, White-Greenwald M (2002) New bone density report format influences patient compliance in filling prescriptions for osteoporosis. Clin J Wom Health 2:13–18

Karter AJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, Ahmed AT, Schmittdiel JA, Selby JV (2009) New prescription medication gaps: a comprehensive measure of adherence to new prescriptions. Health Serv Res 44:1640–1661. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00989.x

Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, Chao CR, Iyer RL, Smith N, Chen W, Jacobsen SJ (2012) Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. The Permanente Journal 16:37–41

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA (1992) Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 45:613–619

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (1989) Applied logistic regression. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Shin J, McCombs JS, Sanchez RJ, Udall M, Deminski MC, Cheetham TC (2012) Primary nonadherence to medications in an integrated healthcare setting. Am J Manag Care 18:426–434

Fischer MA, Choudhry NK, Brill G, Avorn J, Schneeweiss S, Hutchins D, Liberman JN, Brennan TA, Shrank WH (2011) Trouble getting started: predictors of primary medication nonadherence. Am J Med 124(1081):1089–1022. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.05.028

Raebel MA, Ellis JL, Carroll NM, Bayliss EA, McGinnis B, Schroeder EB, Shetterly S, Xu S, Steiner JF (2012) Characteristics of patients with primary non-adherence to medications for hypertension, diabetes, and lipid disorders. J Gen Intern Med 27:57–64. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1829-z

Shah ND, Dunlay SM, Ting HH, Montori VM, Thomas RJ, Wagie AE, Roger VL (2009) Long-term medication adherence after myocardial infarction: experience of a community. Am J Med 122(961):967–913. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.021

Shah NR, Hirsch AG, Zacker C, Taylor S, Wood GC, Stewart WF (2009) Factors associated with first-fill adherence rates for diabetic medications: a cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 24:233–237. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0870-z

Liberman JN, Hutchins DS, Popiel RG, Patel MH, Jan SA, Berger JE (2010) Determinants of primary nonadherence in asthama-controller and dyslipidemia pharmacotherapy. Am J Pharm Benefits 2:111–118

Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X (2008) Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane database of systematic reviews CD000011. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3

Derose SF, Green K, Marrett E, Cheetham TC, Chiu VY, Harrison TN, Reynolds K, Vansomphone SS, Scott RD (2012) Automated outreach to increase primary adherence to cholesterol-lowering medications. Arch Intern Med Published online: doi:10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.717

Gerend MA, Erchull MJ, Aiken LS, Maner JK (2006) Reasons and risk: factors underlying women's perceptions of susceptibility to osteoporosis. Maturitas 55:227–237. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.03.003

Hsieh C, Novielli KD, Diamond JJ, Cheruva D (2001) Health beliefs and attitudes toward the prevention of osteoporosis in older women. Menopause 8:372–376

McHorney CA, Spain CV (2011) Frequency of and reasons for medication non-fulfillment and non-persistence among American adults with chronic disease in 2008. Health Expect 14:307–320. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00619.x

Reginster JY, Rabenda V (2006) Patient preference in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis with bisphosphonates. Clin Interv Aging 1:415–423

Scoville EA, de Leon P, Lovaton P, Shah ND, Pencille LJ, Montori VM (2011) Why do women reject bisphosphonates for osteoporosis? A videographic study. PLoS One 6:e18468. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018468

Yood RA, Mazor KM, Andrade SE, Emani S, Chan W, Kahler KH (2008) Patient decision to initiate therapy for osteoporosis: the influence of knowledge and beliefs. J Gen Intern Med 23:1815–1821. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0772-0

Danese MD, Badamgarav E, Bauer DC (2009) Effect of adherence on lifetime fractures in osteoporotic women treated with daily and weekly bisphosphonates. J Bone Miner Res 24:1819–1826. doi:10.1359/jbmr.090506

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a contractual agreement between Kaiser Permanente Southern California and Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. O’Malley is an employee of Amgen Inc. and owns stock in Amgen Inc. Drs. Muntner, Gold, Silverman, and Morisky have served as advisors for Amgen Inc. Drs. Muntner, Gold and Silverman have served as consultants for Amgen Inc. Drs. Reynolds and Muntner received research support from Amgen Inc. Dr. Silverman has served as an advisor for Lilly, Novartis and Pfizer/Wyeth. Dr. Silverman has served as a consultant for Genentech, Lilly, Novartis and Pfizer/Wyeth. Dr. Silverman has received research support from Lilly and Pfizer/Wyeth. This study was funded by a contractual agreement between Kaiser Permanente Southern California and Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reynolds, K., Muntner, P., Cheetham, T.C. et al. Primary non-adherence to bisphosphonates in an integrated healthcare setting. Osteoporos Int 24, 2509–2517 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2326-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2326-5