Abstract

Alcohol use is highly prevalent globally with numerous negative consequences to human health, including HIV progression, in people living with HIV (PLH). The HIV continuum of care, or treatment cascade, represents a sequence of targets for intervention that can result in viral suppression, which ultimately benefits individuals and society. The extent to which alcohol impacts each step in the cascade, however, has not been systematically examined. International targets for HIV treatment as prevention aim for 90 % of PLH to be diagnosed, 90 % of them to be prescribed with antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90 % to achieve viral suppression; currently, only 20 % of PLH are virally suppressed. This systematic review, from 2010 through May 2015, found 53 clinical research papers examining the impact of alcohol use on each step of the HIV treatment cascade. These studies were mostly cross-sectional or cohort studies and from all income settings. Most (77 %) found a negative association between alcohol consumption on one or more stages of the treatment cascade. Lack of consistency in measurement, however, reduced the ability to draw consistent conclusions. Nonetheless, the strong negative correlations suggest that problematic alcohol consumption should be targeted, preferably using evidence-based behavioral and pharmacological interventions, to indirectly increase the proportion of PLH achieving viral suppression, to achieve treatment as prevention mandates, and to reduce HIV transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite an array of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) to prevent HIV [1], the HIV pandemic continues to affect 35 million people globally with 2.1 million new infections estimated annually [2]. HIV treatment as prevention (TasP) is proposed as a powerful strategy to reduce HIV transmission [3]. In July 2014, UNAIDS called for an ambitious new global target for 90 % of people living with HIV (PLH) to be diagnosed, 90 % of them to be prescribed with antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90 % of them to achieve sustained virological suppression, worldwide [4]. Achieving this 90-90-90 target by 2020 will, by 2030, decrease the HIV/AIDS burden by 90 % from that in 2010 [5]. The HIV care continuum provides a framework for the quantification of attrition, as PLH move in a step-wise fashion from being diagnosed with HIV, to linkage and retention in HIV care, to initiating and adhering to ART, and finally, to achieving sustained virological suppression—ART’s ultimate goal [6].

Despite the documented health and survival benefits from universal ART, irrespective of CD4 count [7••], a number of challenges at each step in the HIV treatment cascade exist. Suboptimal engagement at each step in the HIV treatment cascade limits the effectiveness of HIV prevention efforts, with negative consequences for individuals and public health, including increasing HIV transmission to others. Identifying factors that negatively contribute to poor outcomes in specific populations or resource settings are crucial for care providers, interventionists, policy-makers, and funders.

Though numerous factors have been correlated with decrements in the HIV care continuum, alcohol use disorders (AUDs) contribute prominently by virtue of their sheer societal magnitude. Despite complications from alcohol consumption being a major preventable cause of death [8•], extraordinarily few individuals having a treatable AUD receive treatment [9]. HIV and AUDs are intricately intertwined and mutually reinforcing epidemics that contribute to poor outcomes. These outcomes are exacerbated further in PLH co-infected with HCV infection [10, 11]. AUDs among PLH are two to four times higher than those in the general population [12]. AUDs are associated with increased HIV risk-taking behaviors [13, 14], delays in HIV diagnosis [15], decreased receipt of ART [16], and decreased adherence to ART [16], which may then lead to development of drug resistance, cognitive decline [17, 18], and premature mortality. AUDs potentially negatively impact every stage of the HIV treatment cascade. Interventions aimed towards treating AUDs, therefore, have enormous potential to improve outcomes and increase the number of individuals engaged at each step of the care continuum.

In this paper, we extend a previous systematic review of the impact of AUDs on ART adherence, health-care utilization, and treatment outcomes [16] and we systematically reviewed the more recent literature (2010–2015) on the impact that AUDs have on each stage of the HIV treatment cascade, in the era of recommendations to treat PLH with ART earlier in the course of their disease.

Methods

Literature Search

Ovid (including Medline), Scopus (including Embase), and the Web of Science were queried for original human research published in English from January 2010 until May 2015. References from selected articles were also reviewed for relevant publications. The search strategy combined keywords from each of three conceptual categories: (1) alcohol use disorders (including “alcohol,” “alcoholism,” or “alcohol drinking”), (2) HIV/AIDS (such as “human immunodeficiency virus” or “HIV-1”), and (3) stage of HIV treatment cascade (including “diagnosis,” “linkage to care,” “retention in care,” “adherence,” or “transition to care”).

Study Selection

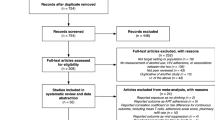

The search in the selected databases yielded a total of 658 articles (Ovid = 22, Scopus = 452, Web of Science = 184) of which 525 remained after eliminating duplicates. The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) patients who drank alcohol at any level or met screening or diagnostic criteria for having an AUD, (2) patients with HIV/AIDS, and (3) reference to one or more components of the HIV treatment cascade including (a) testing and diagnosis, (b) linkage to and (c) retention in care, (d) prescription and initiation of ART, (e) ART adherence, and (f) attainment and maintenance of viral suppression. Reviews, non-peer-reviewed articles, basic or translational science papers, and qualitative research describing experiences rather than associations of AUDs and the HIV cascade were excluded. Papers in languages other than English and those with outcomes other than stages of the HIV treatment cascade such as drinking outcomes, sexual risk behaviors, cognitive outcomes, and HIV risk reduction or HIV prevention were also eliminated. A total of 53 articles were selected after application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for this systematic review.

Data Extraction

Data from identified articles were extracted using a standardized extraction form and included the following: study authors, study site, year and duration of study, World Bank designation for income level of setting, World Health Organization designation of per capita alcohol consumption of the setting, study design, population characteristics, sample size, type of measurement used to measure alcohol use or screen for AUDs, and definition of AUD used. The component of the HIV cascade being evaluated was also noted, including measures of HIV testing, diagnosis, health-care utilization, antiretroviral prescription, ART adherence, and virologic suppression; some assessments targeted more than one step in the care continuum.

Results

Fifty-three studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria, and findings are presented in Table 1. Most studies examined the final stages of the HIV treatment cascade (Fig. 2), ART adherence, and viral suppression. Thirty-three studies focused on alcohol use and ART adherence [19–26, 27•, 28–49, 50•, 51], and 17 targeted viral suppression [21, 25, 33, 35, 50•, 51–53, 54•, 55–62]. Fewer studies, however, focused on the early stages of the cascade with only three examining the association on HIV diagnosis [63, 64, 65•], two on linkage to care [24, 66], four on retention in care [55, 66–68], and seven on ART initiation [24, 54•, 59, 60, 69–71].

Most of the studies (77 %) found that alcohol use, though variably defined, negatively impacted one or more stages of the HIV care continuum, while eight studies found no association. Two studies, which addressed more than one step in the cascade, found a negative association between alcohol use and at least one stage of the cascade as well as no association between alcohol use and another stage of the cascade. Finally, one study found a positive association between alcohol use and a stage of the HIV cascade, namely ART adherence.

Thirty-one studies used cross-sectional study designs and 20 used longitudinal cohort designs. Additionally, there was broad representation of study sites, including from low-, middle-, and high-income settings, as designated by the World Bank, with most settings being from countries that consumed moderate to high (>9 L) levels of alcohol per capita annually. Alcohol consumption was inconsistently defined in multiple ways. Validated screening instruments for AUDs included WHO’s Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [72], which is based on quantifying the number of standardized drinks, while others used the CAGE [73], which is based on symptom severity. Numerous studies, however, defined alcohol use or disorders without referring to standardized measures.

The average annual per capita consumption for each study setting is listed in Table 1 [74]. There is notable variation between countries, with Russia having the highest level, at 15.1 L/person, and Ethiopia, Benin, and Mali having the lowest alcohol consumption levels, at 4.2, 2.1, and 1.1, respectively. The majority of countries here, however, exhibit moderate levels of alcohol use, at 9–11 L/person, e.g., the USA with 9.2 and Uganda with 9.8. There is no association between income level or the annual per capita alcohol consumption and studies that did not find a negative association between alcohol use and a specific step in the HIV treatment cascade. For example, Switzerland is a high-income country with moderate per capita alcohol use (10.7 L), which is one of the studies that found no association between alcohol use and viral suppression. On the other hand, negative associations between alcohol use and specific steps in the HIV treatment cascade were seen in countries with a low level of per capita alcohol use, such as India (4.3 L), as well as those with a high level of per capita alcohol use, such as Russia (15.1 L).

Discussion

As expected based on previous reports [16], most studies reviewed here, but not all, found an association between alcohol consumption, variably and inconsistently defined, and negative consequences on various steps of the HIV treatment cascade. The overwhelming majority of studies focused specifically on how alcohol use affects ART adherence, the step that has previously been of particular interest to many researchers [16]. For most high-income settings, the largest level of attrition is earlier in the HIV treatment cascade, primarily in HIV diagnosis and linkage and retention in HIV care [75••, 76–79]. The mechanism that mediates the effect of alcohol on ART adherence is widely believed to involve cognition and decision-making: impairment after heavy drinking may lead to forgetfulness about taking one’s medications at the appropriate time. Seven studies reviewed here, however, did not find an association between alcohol use and reduced ART adherence [24, 26, 35, 38, 39, 45, 47]. This may be due to the way alcohol consumption and/or ART adherence was defined (self-report, pill count, pharmacy refills, etc.), both of which varied greatly between studies. Three of these studies did not use standardized screening measures for alcohol use [38, 39, 47], but the other four used either the AUDIT [72] or the AUDIT-C [80] or the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) cutoffs [81]. The reasons why these studies did not find an association between alcohol consumption and adherence, while all others did, may have to do with other confounding factors that could have impacted adherence like unstable housing [82] and food insecurity [83], or alternatively, it may be that only those with the highest severity of alcohol consumption (e.g., dependence rather than hazardous or harmful drinking) influenced ART adherence. One study found a positive association between alcohol use and CD4 counts, a measure indirectly related to ART adherence [51]. This unreplicated but provocative study from France showed that compared to no alcohol consumption, low alcohol consumption (<10 g/day) was associated with higher CD4 counts. This low level of alcohol consumption, however, is not associated with having an AUD and would therefore not be amenable to intervention. Lifestyle characteristics, including a culture of leisurely drinking and diet, may be mediating the positive effect of low/moderate alcohol consumption on HIV health outcomes. Moreover, it is important to note that while other studies were focused on problematic alcohol consumption, this was the only one focusing on low-level alcohol consumption.

Seventeen studies examined the impact of alcohol on viral suppression, the final and arguably most important stage of the HIV treatment cascade. Viral suppression has been shown to be of crucial importance for both the HIV-infected individual and the general population. HIV-infected people with early viral suppression are more likely to have direct positive HIV-related health outcomes [84, 85] but also do not contribute appreciably to onward HIV transmission to sexual partners [3]. Most (N = 14) of the 17 studies reviewed found a negative association between alcohol use and viral suppression, yet 3 did not [25, 35, 51]. All the studies used standardized measures of alcohol use, potentially leaving the reasons why no association was found having to do with the populations studied and/or the level of alcohol use severity, or other confounding factors noted previously for the adherence studies. The effect of alcohol use on viral suppression is likely mediated via ART adherence levels, although future studies are needed to address the possibility of a more direct link or, alternatively, the contribution of the types of ART prescribed, including those with longer half-lives that may be more forgiving to intermittent periods of non-adherence [86, 87]. Importantly, the definitions of alcohol consumption and alcohol use severity varied widely between studies and influenced the results of this review. For example, one study differentiated between regular alcohol use and daily alcohol use; it found daily alcohol consumption to be correlated with not achieving viral suppression, whereas regular use, defined by the authors as drinking “a few times a week,” was not [62]. Additionally, ART treatment-experienced patients compared to ART-naïve or newly diagnosed patients are less likely to achieve viral suppression, by virtue of either having baseline genotypic resistance mutations or having been non-adherent previously. Therefore, in studies that do not specify previous ART experience or baseline resistance mutations, the role of alcohol on viral suppression is not clear, making it important to clearly delineate these factors within studies. Last, it is well documented that physicians may defer or withhold ART for PLH with any underlying or perceived substance use disorder. Though most of the data confirming this finding is for people who inject drugs, stereotypes vary in terms of the ways that clinicians view alcohol and whether it is culturally normative for some settings.

A small number of studies focused on the earlier stages of the HIV treatment cascade, specifically those preceding ART adherence. Three studies examined the impact of alcohol use on HIV diagnosis, by primarily examining alcohol use and HIV testing behaviors [63, 64, 65•]. All three studies found that meeting screening criteria for having a treatable AUD was associated with lower levels of HIV testing or, importantly, with being HIV infected and unaware of their HIV-positive status. Two studies of PLH in jail, from the same study sample, did not find an association with having an AUD and being linked to HIV care [24, 66]. Though the sample was large, unique aspects of the sample (i.e., being comprised of jail detainees) who had multiple social, medical, and psychiatric comorbidities that may have interfered considerably with linkage to care or even the measure used for AUDs, previously used cutoffs for the alcohol subscale in the Addiction Severity Index may have influenced the lack of association. Four studies examined retention in care, including the two with jail detainees [24, 66]. Both studies that did not involve jail detainees found an association between alcohol use and poor retention in care [55, 67]. Finally, seven studies focused on ART prescription [24, 54•, 59, 60, 69–71] and most found a negative association between alcohol use and delays in being prescribed with ART, but two studies did not [24, 70]. Most of these studies, however, did not use standardized measures of alcohol use.

While most high-income countries, as classified by the World Bank, have concentrated HIV epidemics among key populations, like men who have sex with men, drug users, and others, many low- or middle-income countries (LMICs) experience generalized epidemics affecting the entire population [88]. Alcohol consumption is highly prevalent in all parts of the world [89], with the exception of a small number of countries where its use is banned or strongly discouraged due to religious restrictions. Importantly, most of the studies reported in this review are from countries with a moderate level of annual drinking per capita (9 to 11 L). With the exception of one study from Russia [68], almost none of the studies were from countries with the highest levels of consumption. In such settings, it will be crucial to not only examine the impact of AUDs on the HIV continuum of care but to also design targeted or structured interventions to reduce problematic alcohol use (e.g., higher taxation for alcohol, increased legal sanctions for intoxication, social marketing campaigns, etc.). When reviewing the presented studies from high-income and LMICs, nearly half (25 out of 53) was conducted in LMICs. Only 2 of 25 studies from LMICs [26, 47] did not find an association between alcohol use and various stages of the cascade. Though there are likely biological and/or sociocultural factors that underlie patterns and severity of alcohol consumption, the World Health Organization recommends standardizing levels of alcohol consumption, though recognizing that quantifying alcohol consumption levels may be challenging as drink sizes vary greatly [90]. Nonetheless, findings here suggest that LMICs face similar issues as high-income countries, where alcohol and HIV treatment are concerned. While there has been an abundance of data stemming from high-income countries, in the past, there were few studies from LMICs. With the majority of PLH now residing in LMICs, the number of studies from these settings included in this review confirms many findings gleaned from high-income settings. It should be noted that the HIV continuum of care has not been standardized globally and each one of its steps is often defined differently based on location [91]. For example, viral suppression has been variably defined at less than 50, 200, and 500 copies/mL thresholds. Thus, in order to better correlate the impact of alcohol and AUDs on the HIV care continuum, it is also crucial to standardize each step of the care cascade.

While countries develop their national guidelines and strategies to combat the HIV epidemic, it will be necessary to incorporate evidence-based interventions (EBIs) that target all types of substance use disorders, including alcohol and drugs, as well as to focus on every step in the continuum of care [92]. Despite CDC’s Compendium of Evidence-Based Interventions and Best Practices for HIV Prevention, which is divided into primary HIV prevention, linkage and retention in care, and ART adherence, few EBIs specifically target problematic alcohol consumption. Absent from most care continuums are primary prevention programs that might include expanded coverage of pre-exposure prophylaxis [93] and increased types (e.g., point-of-care) and frequency of HIV testing [94] for people at risk of HIV infection. An emphasis for using these EBIs for individuals with AUDs is crucial to ensure that the interventions are used for the right target group. Once people are diagnosed with HIV, it is important that they become seamlessly linked to care and stay retained in care. Despite an array of EBIs currently available that targets various components of the HIV care continuum [92], the emergence of interventions that is effective at more than one step in the continuum is likely to have the most effectiveness and traction by public health administrators and policy experts. Moreover, such interventions must be tested and found to be effective in patients with AUDs. Most HIV prevention interventions have either not been tested or adapted to address problematic alcohol consumption. Indeed, detailed analysis of some EBIs shows that individuals with underlying substance use disorders do not fare as well as those without them when the intervention is provided. An important finding here is that, generally, alcohol consumption and/or AUDs negatively contribute to all components of the HIV treatment cascade. Importantly, interventions that directly address alcohol consumption may have a high likelihood of influencing the HIV care continuum for PLH and AUDs.

Evidence from the treatment of opioid use disorders convincingly suggests that addiction treatment is effective for both primary [95] and secondary [69, 96] HIV prevention. The data for treating alcohol use disorders, however, is still emerging. A systematic review of several types of psychosocial interventions (i.e., cognitive-behavioral coping skills, brief interventions, motivational interviewing, and hepatitis health promotion) found little support for their use in reducing alcohol consumption [97]. Though several pharmacological interventions (e.g., naltrexone, acamprosate) have reduced several outcomes associated with alcohol consumption (time to relapse, number of heavy or any drinking days, etc.) [10], the best evidence in comparative controlled trials, however, is the use of pharmacological therapies like naltrexone [98], either in the oral or extended-release injection formulation [99–101]. A systematic review and meta-analysis, however, showed no differences between most pharmacological agents in their ability to reduce relapse to any alcohol use but did find a reduction in days of heavy drinking for most approved (i.e., naltrexone and acamprosate) and some off-label medications [102]. The acceptability of pharmacological treatments for AUDs, however, will be crucial for their uptake [103]. The extent to which alcohol reduction, rather than complete elimination of use, will translate to improvements in each step of the HIV treatment cascade remains likely but unknown and needs empiric support from prospective controlled trials.

Conclusion

This systematic review examined the impact of alcohol use and AUDs on the HIV treatment cascade in recent years, as ART is being expanded to more patients. As guidelines emerge to include immediate ART for all patients irrespective of CD4 counts, factors that influence the HIV care continuum may differ, especially for the latter part of the cascade since ART is sometimes withheld from patients perceived to have problems with alcohol. It is, thus, crucial to holistically establish broad-based interventions that target problematic alcohol consumption so that they may exert their influence across the entire spectrum of the HIV care continuum. Moreover, findings here point to the need for standardization of measures, not only for each step of the treatment cascade but also for measures of alcohol consumption, with an eye towards AUDs that are amenable to treatment. From an international perspective, the use of the AUDIT is validated on every continent and is highly specific and sensitive for identifying AUDs, including levels of severity. The challenge with using the AUDIT, however, is that it relies on individuals to accurately quantify a standard drink, when drinks are context specific, have varying levels of alcohol content, and are not consistently quantified. EBIs that target alcohol use, as well as those targeting the individual stages of the continuum, are needed and should be adequately scaled for high-risk individuals and PLH globally, as part of a concerted effort to reduce both primary and secondary HIV transmission, to improve both individual and public health mandates, and to help eliminate HIV for future generations. Such EBIs may include the Holistic Health Recovery Program (HHRP) [104], which has previously been used to reduce HIV risk and promote ART adherence specifically for PLH with opioid use disorders. Recently, this EBI has been adapted for individuals with AUDs [105] and, if found to be effective, can be disseminated in a variety of settings, including in clinical care, addiction treatment, and community-based settings. Additionally, the CDC, WHO, and UNAIDS have called for integration of addiction treatment in HIV specialty and primary care settings [106, 107], including pharmacological interventions, and there is ongoing research to determine best practices. Such integration has not yet included alcohol treatment within clinical care settings. Ultimately, the best results for improving HIV treatment outcomes in PLH with AUDs will be to ensure high-quality integration of prevention and treatment services that use a wide range of options that are suitable to patients.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Compendium of Evidence-Based Interventions and Best Practices for HIV Prevention Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/complete.html.

Report G. UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2012.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. 90-90-90—an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. New York. 2014. p. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/4/90-90-90. Accessed 12 Mar 2015

Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57.

Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800.

INSIGHT START Study Group, Lundgren JD, Gordin F, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:795–807. The START trial showed that early initiation of antiretroviral therapy (CD4+ count >500) provided net benefits over starting therapy after the CD4+ was <350.

Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E109. Excessive drinking accounts for 1 in 10 deaths among working-age adults in the USA.

Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014

Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):367–87.

Soriano V, Vispo E, Labarga P, Medrano J, Barreiro P. Viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. Antiviral Res. 2010;85(1):303–15.

Petry NM. Alcohol use in HIV patients: what we don’t know may hurt us. Int J STD AIDS. 1999;10(9):561–70.

Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey KB, Cunningham K, Johnson BT, Carey MP, MASH Research Team. Alcohol use predicts sexual decision-making: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental literature. AIDS Behav. 2015 (in press).

Scott-Sheldon LA, Walstrom P, Carey KB, Johnson BT, Carey MP, MASH Research Team. Alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among individuals infected with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis 2012 to early 2013. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(4):314–23.

Zarkin GA, Bray JW, Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC. Alcohol drinking patterns and health care utilization in a managed care organization. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(3):553–70.

Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(3):178–93.

Anand P, Springer SA, Copenhaver MM, Altice FL. Neurocognitive impairment and HIV risk factors: a reciprocal relationship. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1213–26.

Green JE, Saveanu RV, Bornstein RA. The effect of previous alcohol abuse on cognitive function in HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):249–54.

Ajithkumar K, Neera PG, Rajani PP. Relationship between social factors and treatment adherence: a study from South India. Eastern J Med. 2011;16(2):147–52.

Alemu H, Mariam DH, Tsui AO, Shewamare A. Correlates of highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence among urban Ethiopian clients. Afr J AIDS Res. 2011;10(3):263–70.

Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, Sales S, Page JB, Campa A. Alcohol use accelerates HIV disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(5):511–8.

Bhat VG, Ramburuth M, Singh M, Titi O, Antony AP, Chiya L, et al. Factors associated with poor adherence to anti-retroviral therapy in patients attending a rural health centre in South Africa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29(8):947–53.

Broyles LM, Gordon AJ, Sereika SM, Ryan CM, Erlen JA. Predictive utility of brief Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) for human immunodeficiency virus antiretroviral medication nonadherence. Subst Abus. 2011;32(4):252–61.

Chitsaz E, Meyer JP, Krishnan A, Springer SA, Marcus R, Zaller N, et al. Contribution of substance use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes and antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-infected persons entering jail. AIDS Behav. 2013;17 Suppl 2:S118–S27.

Conen A, Wang Q, Glass TR, Fux CA, Thurnheer MC, Orasch C, et al. Association of alcohol consumption and HIV surrogate markers in participants of the Swiss HIV cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(5):472–8.

Farley J, Miller E, Zamani A, Tepper V, Morris C, Oyegunle M, et al. Screening for hazardous alcohol use and depressive symptomatology among HIV-infected patients in Nigeria: prevalence, predictors, and association with adherence. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2010;9(4):218–26.

Ferro EG, Weikum D, Vagenas P, Copenhaver MM, Gonzales P, Peinado J, et al. Alcohol use disorders negatively influence antiretroviral medication adherence among men who have sex with men in Peru. AIDS Care. 2015;27(1):93–104. This study demonstrates that AUDs are associated with sub-optimal adherence among HIV-infected MSM.

Freeman A, Newman J, Hemingway-Foday J, Iriondo-Perez J, Stolka K, Akam W, et al. Comparison of HIV-positive women with children and without children accessing HIV care and treatment in the IeDEA Central Africa cohort. AIDS Care. 2012;24(6):673–9.

Harris J, Pillinger M, Fromstein D, Gomez B, Garris PA, Kanetsky PA, et al. Risk factors for medication non-adherence in an HIV infected population in the Dominican Republic. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(7):1410–5.

Jaquet A, Ekouevi DK, Bashi J, Aboubakrine M, Messou E, Maiga M, et al. Alcohol use and non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients in West Africa. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1416–21.

Jones AS, Lillie-Blanton M, Stone VE, Ip EH, Zhang Q, Wilson TE, et al. Multi-dimensional risk factor patterns associated with non-use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(5):335–42.

Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, White D, Swetsze C, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, et al. Alcohol and adherence to antiretroviral medications: interactive toxicity beliefs among people living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;23(6):511–20.

Kalichman SC, Cherry C, White D, Jones M, Grebler T, Kalichman MO, et al. Sexual HIV transmission and antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort study of behavioral risk factors among men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(1):111–9.

Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, McNerey M, White D, Kalichman MO, et al. Intentional non-adherence to medications among HIV positive alcohol drinkers: prospective study of interactive toxicity beliefs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):399–405.

Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, McNerney M, White D, Kalichman MO, et al. Viral suppression and antiretroviral medication adherence among alcohol using HIV-positive adults. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21(5):811–20.

Kekwaletswe CT, Morojele NK. Patterns and predictors of antiretroviral therapy use among alcohol drinkers at HIV clinics in Tshwane, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2014;26 Suppl 1:78–82.

Kenya S, Chida N, Jones J, Alvarez G, Symes S, Kobetz E. Weekending in PLWH: alcohol use and ART adherence. Pilot Stud AIDS Behavior. 2013;17(1):61–7.

Kowalski S, Colantuoni E, Lau B, Keruly J, McCaul ME, Hutton HE, et al. Alcohol consumption and CD4 T-cell count response among persons initiating antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(4):455–61.

Kozak MS, Mugavero MJ, Ye JT, Aban I, Lawrence ST, Nevin CR, et al. Patient reported outcomes in routine care: advancing data capture for HIV cohort research. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(1):141–7.

Kreitchmann R, Harris DR, Kakehasi F, Haberer JE, Cahn P, Losso M, et al. Antiretroviral adherence during pregnancy and postpartum in Latin America. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(8):486–95.

Malbergier A, Do Amaral RA, Cardoso LD. Alcohol dependence and CD4 cell count: is there a relationship? AIDS Care. 2015;27(1):54–8.

Marks King R, Vidrine DJ, Danysh HE, Fletcher FE, McCurdy S, Arduino RC, et al. Factors associated with nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive smokers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(8):479–85.

Medley A, Seth P, Pathak S, Howard AA, DeLuca N, Matiko E, et al. Alcohol use and its association with HIV risk behaviors among a cohort of patients attending HIV clinical care in Tanzania, Kenya, and Namibia. AIDS Care. 2014;26(10):1288–97.

Morojele NK, Kekwaletswe CT, Nkosi S. Associations between alcohol use, other psychosocial factors, structural factors and antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence among South African ART recipients. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):519–24.

Parsons JT, Starks TJ, Millar BM, Boonrai K, Marcotte D. Patterns of substance use among HIV-positive adults over 50: implications for treatment and medication adherence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;139:33–40.

Rosen MI, Black AC, Arnsten JH, Goggin K, Remien RH, Simoni JM, et al. Association between use of specific drugs and antiretroviral adherence: findings from MACH 14. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):142–7.

Sharma A, Sachdeva RK, Kumar M, Nehra R, Nakra M, Jones D. Effects of lifetime history of use of problematic alcohol on HIV medication adherence. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13(5):450–3.

Teixeira C, Dourado MDL, Santos MP, Brites C. Impact of use of alcohol and illicit drugs by AIDS patients on adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Bahia. Brazil AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(5):799–804.

Venkatesh KK, Srikrishnan AK, Mayer KH, Kumarasamy N, Raminani S, Thamburaj E, et al. Predictors of nonadherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected South Indians in clinical care: implications for developing adherence interventions in resource-limited settings. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(12):795–803.

Woolf-King SE, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Carrico AW, Johnson MO. Alcohol use and HIV disease management: the impact of individual and partner-level alcohol use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2014;26(6):702–8. Hazardous drinkers were shown to be less likely to achieve viral suppression, compared to non-drinkers.

Carrieri MP, Protopopescu C, Raffi F, March L, Reboud P, Spire B, et al. Low alcohol consumption as a predictor of higher CD4+ cell count in HIV-treated patients: a French paradox or a proxy of healthy behaviors? The ANRS APROCO-COPILOTE CO-08 cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(4):e148–e50.

Dahab M, Charalambous S, Karstaedt AS, Fielding KL, Hamilton R, La Grange L, et al. Contrasting predictors of poor antiretroviral therapy outcomes in two South African HIV programmes: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10.

Iralu J, Duran B, Pearson CR, Jiang Y, Foley K, Harrison M. Risk factors for HIV disease progression in a rural southwest American Indian population. Public Health Rep. 2010;125 Suppl 4:43–50.

Kader R, Seedat S, Govender R, Koch JR, Parry CD. Hazardous and harmful use of alcohol and/or other drugs and health status among South African patients attending HIV clinics. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):525–34. This study shows that hazardous/harmful drinkers are less likely to be prescribed with ART.

Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, McKerey M, White D, Kalichman MO, et al. Assumed infectiousness, treatment adherence and sexual behaviours: applying the Swiss Statement on infectiousness to HIV-positive alcohol drinkers. HIV Med. 2013;14(5):263–72.

Lima VD, Kerr T, Wood E, Kozai T, Salters KA, Hogg RS, et al. The effect of history of injection drug use and alcoholism on HIV disease progression. AIDS Care. 2014;26(1):123–9.

Marcellin F, Lions C, Winnock M, Salmon D, Durant J, Spire B, et al. Self-reported alcohol abuse in HIV-HCV co-infected patients: a better predictor of HIV virological rebound than physician’s perceptions (HEPAVIH ARNS CO13 cohort). Addiction. 2013;108(7):1250–8.

McMahon JH, Manoharan A, Wanke C, Mammen S, Jose H, Malini T, et al. Targets for intervention to improve virological outcomes for patients receiving free antiretroviral therapy in Tamil Nadu, India. AIDS Care. 2014;26(5):559–66.

Shacham E, Agbebi A, Stamm K, Overton ET. Alcohol consumption is associated with poor health in HIV clinic patient population: a behavioral surveillance study. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):209–13.

Skeer MR, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, O’Cleirigh C, Covahey C, Safren SA. Patterns of substance use among a large urban cohort of HIV-infected men who have sex with men in primary care. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):676–89.

Sullivan KA, Messer LC, Quinlivan EB. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV/AIDS (SAVA) syndemic effects on viral suppression among HIV positive women of color. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29 Suppl 1:S42–8.

Wu ES, Metzger DS, Lynch KG, Douglas SD. Association between alcohol use and HIV viral load. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(5):e129–e30.

Bengtson AM, L’Engle K, Mwarogo P, King’ola N. Levels of alcohol use and history of HIV testing among female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2014;26(12):1619–24.

Fatch R, Bellows B, Bagenda F, Mulogo E, Weiser S, Hahn JA. Alcohol consumption as a barrier to prior HIV testing in a population-based study in rural Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1713–23.

Vagenas P, Ludford KT, Gonzales P, Peinado J, Cabezas C, Gonzales F, et al. Being unaware of being HIV-infected is associated with alcohol use disorders and high-risk sexual behaviors among men who have sex with men in Peru. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):120–7. This study with a large sample of MSM in Peru showed that AUDs are associated with being unaware of being HIV infected.

Althoff AL, Zelenev A, Meyer JP, Fu J, Brown SE, Vagenas P, et al. Correlates of retention in HIV care after release from jail: results from a multi-site study. AIDS Behav. 2013;17 Suppl 2:S156–70.

Lifson AR, Demissie W, Tadesse A, Ketema K, May R, Yakob B, et al. Barriers to retention in care as perceived by persons living with HIV in rural Ethiopia: focus group results and recommended strategies. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2013;12(1):32–8.

Pecoraro A, Mimiaga M, O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA, Blokhina E, Verbitskaya E, et al. Depression, substance use, viral load, and CD4+ count among patients who continued or left antiretroviral therapy for HIV in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation. AIDS Care. 2015;27(1):86–92.

Altice FL, Bruce RD, Lucas GM, Lum PJ, Korthuis PT, Flanigan TP, et al. HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected, opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone treatment within HIV clinical care settings: results from a multisite study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S22–32.

Neblett RC, Hutton HE, Lau B, McCaul ME, Moore RD, Chander G. Alcohol consumption among HIV-infected women: impact on time to antiretroviral therapy and survival. J Womens Health. 2011;20(2):279–86.

Santos GM, Emenyonu NI, Bajunirwe F, Rain Mocello A, Martin JN, Vittinghoff E, et al. Self-reported alcohol abstinence associated with ART initiation among HIV-infected persons in rural Uganda. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134(1):151–7.

Babor TF, Delafuente JR, Saunders J. AUDIT: the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905–7.

WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Lourenco L, Hull M, Nosyk B, Montaner JSG, Lima VD. The need for standardisation of the HIV continuum of care. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(6):e225–e6. This paper describes how stages of the HIV continuum of care are defined differently in different locations and urges for standardization across the world.

Pineirua A, Sierra-Madero J, Cahn P, Guevara Palmero RN, Martinez Buitrago E, Young B, et al. The HIV care continuum in Latin America: challenges and opportunities. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(7):833–9.

Skarbinski J, Rosenberg E, Paz-Bailey G, Hall HI, Rose CE, Viall AH, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus transmission at each step of the care continuum in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015;175(4):588–96.

Parchure R, Kulkarni V, Kulkarni S, Gangakhedkar R. Pattern of linkage and retention in HIV care continuum among patients attending referral HIV care clinic in private sector in India. AIDS Care. 2015;27(6):716–22.

Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ, Van Handel MM, Stone AE, LaFlam M, et al. Vital signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(47):1113–7.

Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–95.

McLellan AT, Cacciola JC, Alterman AI, Rikoon SH, Carise D. The Addiction Severity Index at 25: origins, contributions and transitions. Am J Addict. 2006;15(2):113–24.

Palepu A, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Zhang R, Wood E. Homelessness and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among a cohort of HIV-infected injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2011;88(3):545–55.

Anema A, Weiser SD, Fernandes KA, Ding E, Brandson EK, Palmer A, et al. High prevalence of food insecurity among HIV-infected individuals receiving HAART in a resource-rich setting. AIDS Care. 2011;23(2):221–30.

Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Westfall AO, Crane HM, Zinski A, Willig JH, et al. Early retention in HIV care and viral load suppression: implications for a test and treat approach to HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(1):86–93.

Costagliola D, Ledergerber B, Torti C, van Sighem A, Podzamczer D, Mocroft A, et al. Predictors of CD4(+) T-cell counts of HIV type 1-infected persons after virologic failure of all 3 original antiretroviral drug classes. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(5):759–67.

Bruce RD, Moody DE, Altice FL, Gourevitch MN, Friedland GH. A review of pharmacological interactions between HIV or hepatitis C virus medications and opioid agonist therapy: implications and management for clinical practice. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6(3):249–69.

Ing EC, Bae JW, Maru DS, Altice FL. Medication persistence of HIV-infected drug users on directly administered antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):113–21.

NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Sexually transmitted disease and HIV prevalence and risk factors in concentrated and generalized HIV epidemic settings. AIDS. 2007;21 Suppl 2:S81–90.

WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

World Health Organization (WHO). International guide for monitoring alcohol consumption and related harm. Geneva: Dependence DoMHaS; 2000.

Lourenço L, Hull M, Nosyk B, Montaner JS, Lima VD. The need for standardisation of the HIV continuum of care. Lancet HIV. 2015;2:e225–6.

Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Challenges in managing HIV in people who use drugs. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2015;28(1):10–6.

Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2587–99.

Stevens W, Gous N, Ford N, Scott LE. Feasibility of HIV point-of-care tests for resource-limited settings: challenges and solutions. BMC Med. 2014;12:173.

MacArthur GJ, Minozzi S, Martin N, Vickerman P, Deren S, Bruneau J, et al. Opiate substitution treatment and HIV transmission in people who inject drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345, e5945.

Edelman EJ, Chantarat T, Caffrey S, Chaudhry A, O’Connor PG, Weiss L, et al. The impact of buprenorphine/naloxone treatment on HIV risk behaviors among HIV-infected, opioid-dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;139:79–85.

Klimas J, Tobin H, Field CA, O’Gorman CS, Glynn LG, Keenan E, et al. Psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12, CD009269.

Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003–17.

Pettinati HM, Silverman BL, Battisti JJ, Forman R, Schweizer E, Gastfriend DR. Efficacy of extended-release naltrexone in patients with relatively higher severity of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1804–11.

O’Malley SS, Garbutt JC, Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Kranzler HR. Efficacy of extended-release naltrexone in alcohol-dependent patients who are abstinent before treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(5):507–12.

Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, Gastfriend DR, Pettinati HM, Silverman BL, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1617–25.

Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, Bobashev G, Thomas K, Wines R, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889–900.

Brown SE, Vagenas P, Konda KA, Clark JL, Lama JR, Gonzales P, et al. Men who have sex with men in Peru: acceptability of medication-assisted therapy for treating alcohol use disorders. Am J Mens Health. 2015 (in press).

Copenhaver MM, Tunku N, Ezeabogu I, Potrepka J, Zahari MM, Kamarulzaman A, et al. Adapting an evidence-based intervention targeting HIV-infected prisoners in Malaysia. AIDS Res Treat. 2011;2011, 131045.

Armstrong ML, LaPlante AM, Altice FL, Copenhaver MM, Molina PE. Advancing behavioral HIV prevention: adapting an evidence-based intervention for people living with HIV and alcohol use disorders. AIDS Research and Treatment. 2015 (in press).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Integrated prevention services for HIV infection, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and tuberculosis for persons who use drugs illicitly: summary guidance from CDC and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-5):1–40.

WHO/UNODC/UNAIDS. Policy guidelines for collaborative TB and HIV services for injecting and other drug users: an integrated approach 2008. December 16, 2008. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596930_eng.pdf. Accessed 16 Dec 2008.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Funding Source

This review was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) through research (R01 DA032106) and career development (K24 DA017072 and K02 DA033139) awards and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (R01 AA018944 and U01 AA021995). The funding sources played no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Vagenas, Dr. Azar, Dr. Copenhaver, and Dr. Springer declare that they have no conflict of interest. Dr. Molina reports personal fees and non-financial support from the National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Council Member), outside the submitted work. Dr. Altice reports Speakers Bureau (Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Gilead, Rush University Simply Speaking HIV, Practice Point Communications Grant Funds to Yale University) with Dr. Altice as PI (NIH, NIAAA, SAMHSA, HRSA, Gilead Foundation).

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

Research involving human subjects, human material, or human data was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the appropriate ethics committee (Institutional Review Boards of Yale University, Asociacion Civil Impacta Salud y Educacion (Peru), Emory University, and Abt Associates). All research was carried out within the appropriate ethical framework.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Behavioral-Bio-Medical Interface

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vagenas, P., Azar, M.M., Copenhaver, M.M. et al. The Impact of Alcohol Use and Related Disorders on the HIV Continuum of Care: a Systematic Review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 12, 421–436 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-015-0285-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-015-0285-5