Abstract

We provide a comprehensive review of the growth of multinational enterprises (MNEs) based on a quarter-century (25 years) of scholarly international business publications. We synthesize research insights on the determinants of the growth of MNEs through the lens of Penrose’s theory of firm growth, which is the most influential theoretical perspective on firm growth. The review takes stock of the research findings on the facilitators, constraints, and the trajectory of growth of MNEs, and elaborates on the commonalities and differences between research on the growth of MNEs that draws on Penrose’s theory and research that does not. This comparison highlights the opportunity to build an internally coherent theory of the growth of MNEs, that is, a theory that connects ‘what an MNE is’ to ‘what determines an MNE’s growth.’ It also indicates that past research placed a strong emphasis on exogenous factors (e.g., cross-country distances) as key constraints on growth even though the Penrosean lens suggests a close consideration of endogenous factors that drive international growth, as well as endogenizing the ostensibly exogenous growth determinants. The review highlights the importance of firm-specific managerial knowledge and learning, which shapes the direction of the growth of MNEs and ensures its administrative coherence.

Résumé

Nous proposons une étude complète sur la croissance des entreprises multinationales (EMN) fondée sur un quart de siècle (25 ans) de publications scientifiques relatives à l’international business. Nous synthétisons les résultats des recherches sur les déterminants de la croissance des EMN à travers le prisme de la théorie de Penrose sur la croissance des entreprises, qui est la perspective théorique la plus influente sur la croissance des entreprises. L’étude fait le point sur les résultats des recherches sur les facteurs de facilitation, les contraintes et la trajectoire de croissance des EMN, et précise les points communs et les différences entre les recherches sur la croissance des EMN qui s’appuient sur la théorie de Penrose et les recherches qui ne l’utilisent pas. Cette comparaison met en évidence la possibilité de construire une théorie cohérente en interne sur la croissance des EMN, c’est-à-dire une théorie qui relie «ce qu’est une multinationale à «ce qui détermine la croissance d’une EMN». Elle indique également que les recherches passées ont mis l’accent sur les facteurs exogènes (par exemple, les distances entre pays) comme contraintes clés de la croissance, même si l’approche de Penrose suggère de prendre en compte les facteurs endogènes qui sont le moteur de la croissance internationale, ainsi que d’endogénéiser les déterminants de la croissance apparemment exogènes. L’étude souligne l’importance des connaissances et de l’apprentissage managériaux propres à l’entreprise, qui déterminent l’orientation de la croissance des EMN et assurent sa cohérence administrative.

Resumen

Proporcionamos una revisión exhaustiva del crecimiento de las empresas multinacionales (EMNs por sus iniciales en inglés) basada en un cuarto de siglo (25 años) de publicaciones académicas de negocios internacionales. Sintetizamos ideas de investigación sobre los determinantes del crecimiento de las empresas multinacionales a través de la lente de la teoría de Penrose sobre el crecimiento de la empresa, que es la perspectiva teórica más influyente sobre el crecimiento de la empresa. La revisión hace un balance de los hallazgos de la investigación sobre los facilitadores, las limitaciones y la trayectoria del crecimiento de las empresas multinacionales, y profundiza en los puntos en común y las diferencias entre la investigación sobre el crecimiento de las empresas multinacionales que se basa en la teoría y la investigación de Penrose que no lo hace. Esta comparación resalta la oportunidad de construir una teoría internamente coherente del crecimiento de las empresas multinacionales, es decir, una teoría que conecta “lo que es una empresa multinacional” con “lo que determina el crecimiento de una empresa multinacional. También indica que investigaciones anteriores pusieron un fuerte énfasis en los factores exógenos (por ejemplo, distancias entre países) como restricciones clave en el crecimiento a pesar de que la lente Penrosiano sugiere una consideración estrecha de los factores endógenos que impulsan el crecimiento internacional, así como endogenizar los determinantes del crecimiento ostensiblemente exógeno. La revisión destaca la importancia del conocimiento y aprendizaje gerenciales específicos de las empresas, lo que da forma a la dirección del crecimiento de las empresas multinacionales y asegura su coherencia administrativa.

Resumo

Fornecemos uma revisão abrangente do crescimento de empresas multinacionais (MNEs) com base em um quarto de século (25 anos) de publicações acadêmicas em negócios internacionais. Sintetizamos insights de pesquisa sobre os determinantes do crescimento de MNEs através da lente da teoria de Penrose sobre o crescimento da firma, que é a perspectiva teórica mais influente sobre o crescimento da firma. A revisão faz um balanço de achados da pesquisa sobre facilitadores, restrições e trajetória de crescimento de MNEs e elabora sobre pontos em comum e diferenças entre a pesquisa sobre o crescimento das MNEs que se apoia na teoria de Penrose e a pesquisa que não se apoia. Essa comparação destaca a oportunidade de construir uma teoria internamente coerente do crescimento de MNEs, isto é, uma teoria que conecta ‘o que uma MNE é’ a ‘o que determina o crescimento de uma MNE’. Ela igualmente indica que pesquisas anteriores enfatizaram fortemente fatores exógenos (por exemplo, distâncias entre países) como principais restrições ao crescimento, embora a lente de Penrose sugira uma consideração cuidadosa de fatores endógenos que impulsionam o crescimento internacional, bem como da endogenização de determinantes de crescimento ostensivamente exógenos. A revisão destaca a importância do conhecimento e aprendizado gerenciais específicos da empresa, que molda a direção do crescimento de MNEs e assegura sua coerência administrativa.

摘要

我们基于四分之一世纪(25年)的国际商务学术出版物, 对跨国企业(MNE)成长进行了全面的综述。我们通过关于公司成长最有影响力的彭罗斯(Penrose)公司成长理论的视角, 综合了关于MNE成长决定因素的研究见解。本综述总结了MNE成长的推动因素、制约因素和发展轨迹的研究结果, 并阐述了借鉴与没借鉴彭罗斯理论的MNE成长研究之间的共性和差异。这种比较凸显了建立内部贯连的MNE成长理论的机会, 也就是将“MNE是什么”与“什么决定MNE的成长”联系起来的理论。它也表明, 以往的研究重点强调外生因素(例如,跨国距离)是成长的主要限制因素, 尽管彭罗斯视角建议周密考虑驱动国际成长的内生因素, 以及表面上的外生成长决定因素的内生化。本综述强调了决定MNE成长方向并确保其行政连贯性的公司特定的管理知识和学习的重要性。

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Growth is a fundamental concept in the research related to multinational enterprises (MNEs). In mainstream international business (IB) research, such as research on the entry into foreign markets and the internationalization processes, growth is essentially an implicit corporate objective, although some studies have focused explicitly on the growth of MNEs (Belderbos & Zou, 2007; Hutzschenreuter, Voll, & Verbeke, 2011; Tan, 2009). International expansion involves the corporate-level decision to pursue profitable growth in foreign markets (Buckley & Casson, 2007; Meyer, 2006). The growth of MNEs is manifested by sequential expansion of their subsidiaries in existing host countries as well as their entries into other countries. Since growth constitutes “an evolutionary process” (Penrose, 1959/1995: xiii), research on divestments and exits of MNEs also contributes to our understanding of the growth trajectory of multinational firms.

In this review paper, we synthesize research insights on the determinants of the growth of MNEs through the lens of Edith Penrose’s (1959) seminal book, The Theory of the Growth of the Firm,1 to develop a more coherent and comprehensive understanding of research on the growth of MNEs and envision opportunities for future research. We chose Penrose (1959) as a guiding framework in our review because her theory is the most influential reference (highest citation count) in management research on the growth of firms (Zupic & Drnovsek, 2014). The IB research community also has recognized the importance of Penrose’s work.2 Penrose was the second scholar to receive the John Fayerweather Eminent Scholar Award given by the Academy of International Business fellows. Prominent IB scholars, including Buckley, Casson, Dunning, Pitelis, Teece, and Verbeke, have shown that Penrose’s (1959) insights on the nature of the firm and its growth have implications for MNE research. Her work also influenced the development of the influential internationalization process model (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017). Although Penrose’s work, especially her conceptualization of a firm as a collection of productive resources, has been extended to resource- and capability-based theories of firms, these theories focus primarily on the characteristics of resources and capabilities to explain and predict the heterogeneity of firm-level performance. Yet, at the center of Penrose’s (1959) theory is the profitable growth of the firm (Augier & Teece, 2007; Kor & Mahoney, 2000, 2004; Rugman & Verbeke, 2002). Penrose’s attention to the drivers, constraints, and processes of growth provides a framework for organizing and synthesizing the various determinants found in research on the growth of MNEs. Resource-based and in particular dynamic capabilities approaches (Teece, 2014) also offer important insights about how versatile resources and (dynamic) capabilities of firms can enable them to achieve long-term profitable growth in fast-paced changing environments. Thus, we take note of these insights in our review of firm-specific resources as facilitators of the growth of MNEs.

We submit that taking stock of research related to the growth of MNEs with a framework inspired by Penrose’s growth theory can enable scholars to make better sense of the accumulated research insights, which are rich but remain scattered across different studies with different theoretical roots, levels of analysis (e.g., firm vs. subsidiary growth), and national contexts. With a focus on the facilitators, constraints, and processes of a firm’s growth, this framework facilitates the organization and synthesis of the insights, which then can guide new research on the growth of MNEs.

In addition, this review provides an opportunity to elaborate on the similarities and differences between research on the growth of MNEs that draws on Penrose’s growth theory and research that does not. This comparison enables us to reflect on concepts and ideas that have not been examined thoroughly in the research related to the growth of MNEs. One of these under-examined ideas is firm-specific managerial learning. Even though the extant research regularly cites Penrose’s (1959) conceptualization of the firm as a unique bundle of resources, it often neglects the idea that managerial choices shape the productive services of resources, and the interactions between managers and resources jointly drive the growth of firms. Thus, managerial knowledge about the firm’s unique resources or firm-specific managerial learning can contribute to the creation of new productive resources that facilitate international growth. Our review of research on the growth of MNEs suggests that this research has emphasized the role of host-country knowledge while giving insufficient attention to firm-specific managerial knowledge and learning. However, for an MNE, either as a hierarchy (administrative organization) that relies on managers to allocate resources (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Hennart, 1982) or as a group of geographically dispersed and goal-disparate organizations (Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1990), firm-specific managerial knowledge can be crucial in maintaining organizational coherence (Teece, Rumelt, Dosi, & Winter, 1994). Such firm-specific knowledge and organizational coherence are needed for effective coordination and knowledge transfer (Cantwell, Dunning, & Lundan, 2010), and for curbing managerial opportunism (Hoenen & Kostova, 2015) as part of the successful pursuit of long-term profitable growth for the overall MNE.

This comparison also allows scholars to consider developing an internally coherent theory of the growth of MNEs, which connects ‘what an MNE is’ to ‘what determines an MNE’s growth.’ Penrose and dominant foreign direct investment (FDI) theories (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Hennart, 1982) share a similar notion of firms as administrative organizations that rely on managers to allocate resources. In Penrose’s theory, ‘what a firm is’ explains ‘how the firm grows,’ and the underpinning logic derives the necessary and sufficient conditions for growth as well as its constraints. However, in IB research, discussions on how ‘an MNE functions’ and ‘how an MNE grows’ are in different streams of research. This separation results in an incomplete understanding of the process by which an MNE grows as an administrative organization.

Finally, Penrose (1959) offers an endogenous growth model in which growth determinants are generated internally, and the external environment is perceived subjectively and could be strategically influenced by managerial actions. While MNE research recognizes some of the endogenous aspects of profitable growth (such as experiential learning in foreign markets), it places a strong emphasis on exogenous factors, such as cross-country distances, as key constraints on growth. Our review highlights research opportunities based on a close consideration of endogenous factors that drive international growth, as well as endogenizing some of the ostensibly exogenous growth determinants.

The next section provides an overview of Penrose’s theory of the growth of the firm to develop a framework for organizing our review of research on the growth of MNEs. Next, we explain our review methodology and present our review and synthesis of the literature through a Penrosean lens. Then, in connection with the review and research gaps we identified, we offer our suggestions for new directions for future research.

PENROSE’S GROWTH THEORY

In Penrose’s (1959) theory, the determinants of the growth of the firm derive from a conceptualization of the firm and its objective. Thus, we summarize the theory in terms of (1) the nature of a firm, (2) the objective of the firm, (3) the (facilitating and constraining) determinants of the growth of the firm, and (4) the growth trajectory of the firm.

What is a firm? In Penrose’s (1959) theory, a firm is an administrative organization that requires managerial decision-making (Barnard, 1938; Simon, 1947). As Penrose elaborates, “a firm is… a collection of productive resources the disposal of which between different uses and overtime is determined by administrative decision” (1959: 24). This conceptualization of a firm offers a foundation for firm heterogeneity based on the firm’s bundle of resources and the central role of managers in shaping and utilizing these resources. Specifically, managers act as catalysts in converting a firm’s resources into productive services (Mahoney, 1995) through decisions on resource development, deployment, utilization, and combination. We note that Penrose’s conceptualization of a firm, as an administrative organization, is similar to international business (IB) research on internalization theory. In particular, the use of authority or managerial fiat to organize exchanges is the raison d’être for multinational firms and what distinguishes them from market mechanisms (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Hennart, 1982).

What is the objective of the firm? Penrose submits that the objective of the firm is long-term growth through investing in profitable expansion (1959: 29). Because a firm is not confined to particular products or locations, “there are opportunities for profitable investment open somewhere in the economy” (1959: 43). Penrose offers product diversification as a solution for unfavorable external conditions, and, in this vein, a firm’s entry into new foreign markets also can be a profitable growth solution to stagnant home and host markets. Therefore, new foreign entries, along with subsequent growth in existing host markets, constitute the MNE’s overall growth.

What facilitates the growth of the firm? Penrose maintains that the growth of the firm is derived from internal facilitators, which include underutilized firm resources, innovation, and managerial learning. She posits that, as long as current operations do not fully utilize productive resources, “there is an incentive for a firm to find a way of using them more fully” (1959: 67). In Penrose’s theory, what makes resources underutilized is their indivisibility (e.g., lumpy physical capital) and fungibility (Augier & Teece, 2007), as well as ‘resource learning’ (the creation of new knowledge) during ongoing operations of the firm (1959: 69). These underutilized resources facilitate further innovation as managers experiment with new resource combinations to more fully and productively utilize existing resources through the growth of the firm (1959: 86).

Managerial learning also is an important driver of the growth of firms. Learning increases and enriches managers’ tacit knowledge about the bundle of resources in the firm, which in turn expands the range of productive services from those resources (1959: 5). Thus, the growth of a firm is a dynamic process of management interacting with resources (Kor, Mahoney, Siemsen, & Tan, 2016). In addition, Penrose considers managers’ entrepreneurial capabilities as crucial for the firm’s growth (1959: 8). Entrepreneurial capabilities consist of the ability to shape creative imagination and vision for the firm (1959: 36), the ability to create confidence in investors (1959: 38), and the ability to develop and utilize information-gathering and consulting facilities that enable managers to evaluate and manage risk and uncertainty in different growth directions (1959: 41). These capabilities enable firms to continue to create or discover new markets to utilize their resources fully.

What constrains the growth of the firm? Penrose emphasizes that the binding constraint on the profitable growth of a firm arises from the need for managers to accumulate firm-specific knowledge, which is essential for formulating and implementing growth plans. However, it takes time for managers to accumulate this knowledge. Thus, firms face an inelastic supply of managerial services in the short run because no such labor market exists.

Penrose does not consider external conditions as serious barriers to growth because a firm can always escape stagnant markets by diversifying into other product markets or geographical locations (1959: 43). According to Penrose, the notion that a firm’s growth is inhibited by external conditions typically should be attributed to its lack of entrepreneurial capabilities. She acknowledges that it is difficult for a firm to diversify into entirely new areas of specialization, and she favors finding new markets in which the firm can build on its existing competencies (1959: 130). This early Penrosean insight is consistent with research that empirically corroborates and explains why firms are more successful when conducting related rather than unrelated product diversification (Teece, 1982). Similarly, for international expansion, it is difficult for a firm to penetrate a distant host country because its under-utilized resources can be costly to transfer across borders (Rugman & Verbeke, 2003). Dissimilarity between the firm’s existing activities and markets and the new activities (and the new market conditions) increases the amount of managerial services required for the successful execution of international entrepreneurial activities (Verbeke & Yuan, 2007); this managerial bottleneck reduces the speed of international expansion (Hutzschenreuter et al., 2011).

Growth trajectory The managerial constraint on the growth of a firm, or the so-called “Penrose effect” (Shen, 1970; Slater, 1980), predicts that a fast-growing firm will encounter managerial problems that impede its growth in the subsequent time period. The Penrose effect has been corroborated empirically in both domestic and international contexts (e.g., Hashai, 2011; Mohr, Batsakis, & Stone, 2018). Penrose (1959) describes an endogenous model of the growth of a firm in which managerial learning within the firm can facilitate and constrain the growth of the firm (Pitelis, 2000). This endogenous model implies that firms can manage their own growth through careful organizational design. The upshot of Penrose’s theory is the message that management matters.

Even though Penrose (1959) did not explain the process and the growth of MNEs explicitly,3 a few prominent IB scholars have extended Penrosean theory to explain and predict the growth of MNEs. For example, internationalization process theory (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 1990), which is influenced by Penrose’s growth theory, presents the process of international expansion as an iterative process of commitment to host markets and learning that leads to the accumulation of knowledge about the markets. Dynamic capabilities (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), for which Augier and Teece (2007) credit Penrose (1959) as being an inspiration, consider the firm’s ability to shape and configure resource bases to respond to changing technologies and markets as the foundations for long-term profitable growth of firms. Augier and Teece (2007) suggest that, while Penrose might not have fully developed the capability concept for MNEs, the development of the dynamic capability approach can be applied usefully to MNEs. Teece (2014) emphasizes dynamic capabilities and the importance of entrepreneurial management and transformational leadership in enabling MNEs to sustain performance in changing global environments. Furthermore, Buckley and Casson (2007) offer a mathematical model of Penrose’s growth theory that considers international expansion and product diversification as alternative growth directions, and it incorporates technological innovation as a key driver of growth in which decreasing returns to R&D act as a growth constraint. Building on Penrose, Dunning (2003) identifies a number of conditional ownership advantages that accrued to large, multinational firms, which can be the basis for MNEs achieving profitable growth. Relatedly, Pitelis (2002) articulates Penrosean insights relevant to Dunning’s (1980) ownership, location, and internalization (OLI) paradigm and explained how Penrose’s work can contribute to theories on foreign direct investment (FDI) and enhance the understanding of the growth of MNEs. Pitelis and Verbeke (2007) propose three ways of extending Penrose’s theory to explain the growth of MNEs, including technology-based firm-specific advantages, dynamic capabilities, and integrating location-bound and internationally transferable knowledge. Verbeke and Yuan (2007) apply Penrose’s ideas to propose three conditions under which firms are more likely to encounter managerial constraints, such as a broad scope and high complexity of international activities, dissimilarity between existing and new activities, and dissimilarity between existing and new market conditions. In addition to these conceptual contributions, several empirical studies have drawn from Penrose (1959) to examine the growth of MNEs, which we discuss in the review section of this paper.

REVIEW METHODOLOGY

Penrose’s (1959) theory provides useful guidance for constructing our review of research on the determinants of the growth of MNEs. In particular, Penrose considers diversification as a general growth policy in which growth is not restricted to particular geographical or product markets. Therefore, new entry and sequential expansion in a particular foreign market (either in the form of growth of the subsidiary or establishment of additional subsidiaries) contribute to the growth of MNEs. In addition, Penrose’s assumption that firms seek profitable growth implies that divestments and exit activities of MNEs ultimately are part of the growth process. Thus, we consider such research relevant in our literature review.4 Given space limitations and the considerable amount of literature on foreign market entry, we focused on the conceptual and empirical articles published between 1995 and 2019 in leading management journals, e.g., Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review, Administrative Science Quarterly, Journal of Management, Journal of Management Studies, Organization Science, and the Strategic Management Journal. Also, we focused on leading IB-specific journals from 1995 to 2019, including the Journal of International Business Studies, Global Strategy Journal, Journal of World Business, and Management International Review. Thus, we curated scholarly publications dating back for a quarter of a century. We searched titles and abstracts of these targeted journals for the keywords of grow/growth, market entry, expand/expansion, internationalize/internationalization, (internationalise/internationalisation), speed, trajectory, evolve/evolution, exit/survival, divest/divestment, downsize/downsizing, and Penrose/Penrosean. Our initial search identified 3020 articles, and we reviewed the titles and abstracts of the articles for relevance. Many articles were eliminated due to their lack of international content. Further, for the Journal of International Business Studies, the flagship journal that focuses on international business research, we reviewed the title and abstract of each article for all issues over the study period, thereby identifying six additional articles. These search processes produced 190 articles that are of interest. Next, we searched titles and abstracts of the targeted journals for the keywords of international performance and international diversification, because studies that focus on these topics might measure performance based on growth. This search yielded 1244 articles, 68 of which appeared in our earlier keyword search. We reviewed the titles, abstracts, and the methodology sections of all of the remaining articles; we identified nine additional articles with dependent variables that consist of at least one measure of growth. Combining this with the 190 articles, our final sample consists of 199 articles (see Online Appendix).

Note that our review focus on research related to the growth of MNEs. Although Penrose’s work on MNEs (e.g., 1959, 1968, 1973) focused mainly on the impact of MNEs on the economic welfare of host countries (Dunning, 2003; Pitelis, 2004; Rugman & Verbeke, 2002), our review does not cover this topic because it has been well covered elsewhere. On this topic, interested readers could refer to recent reviews on the impact of MNEs on host economies, such as spillovers (Abebe & Begum, 2016; Meyer & Sinani, 2009) and host-country competition (Forte, 2015).

A REVIEW OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS RESEARCH ON MNE GROWTH

Overview of the Focus in Research on MNE Growth

Our literature review consists of 199 articles in which the research inquiries are focused on the determinants of the growth of MNEs, which could be the result of entering new foreign markets as well as expansion/divestment in the host country. To understand how the focus of the research evolved, we classified all articles into five key categories: (1) growth via initial entry into foreign markets; (2) sequential expansion in the foreign markets; (3) survival, exit, or divestment; (4) overall growth of the MNE in the form of international scope and intensity (including international diversification and multinationality); and (5) the growth trajectories of the MNEs. These categories are not mutually exclusive, and we assigned some articles to more than one category. For example, Nachum and Song (2011) examine whether MNE characteristics have different impacts on their foreign expansion and contraction. Therefore, this journal article was classified under both category (1) and category (3). Figure 1a shows the number of articles in each category for every 5-year period from 1995 to 2019. Overall, the number of studies on the growth of MNEs has been increasing in recent years. Studies on foreign market entry constitute the largest research category in the research relative to the growth of MNEs (approximately 32% of our review articles), and this is followed by studies on the international scope and intensity (28%). These two categories received substantial research attention because they represent fundamental inquiries associated with the existence of MNEs. Approximately 24% of the studies focus on survival, exit, and divestment as well as subsequent expansion (21%). Research on the trajectory of the growth of MNEs received less attention (9%), probably because this topic requires longitudinal data, which are difficult to attain. In summary, Fig. 1a shows that four areas of research, i.e., foreign market entry, sequential expansion, multinationality, and growth trajectory, increased over the study period (1995–2019), indicating that the growth of MNEs is a trending issue in the IB research literature.

a Proportion of sample articles by topic. Note: The sum of all of the percentages is greater than 100% because some articles were classified under two or more topics. The percentage of articles in 2016-2019 includes six articles that were accepted in 2018, 2019, or early 2020 but not in print as of March 2020. b Numbers of articles in the review that cite Penrose (1959) by topic. Note: Some articles were classified under two or more topics. Percentages are calculated as the numbers of articles that cite Penrose divided by the total numbers of articles in each of the specific topics on growth.

Given that we use Penrose’s growth theory to organize our review, we consider how many and what types of studies on MNE growth cited Penrose. Figure 1b classifies the articles that cite Penrose by our five categories, and it shows that Penrose’s theory is relevant to every topic related to MNE growth, but it is particularly influential concerning the topic of growth trajectory, in which 39% of the articles cite Penrose’s work. Her direct influence on the other categories is reflected by the citation percentages of 32% for expansion in foreign markets, 23% for foreign market entry, 15% for survival, exit, and divestment, and 16% for international scope and intensity.

Overview of the Determinants of MNE Growth

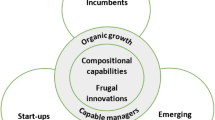

Given that Penrose’s theory pays central attention to the facilitators, constraints, and process of the growth of firms, we present our review in three sections that summarize and synthesize research findings of the facilitators, constraints, and trajectory of the growth of MNEs. Facilitators are theoretically grounded factors that enhance the growth of MNEs, where growth can take the form of new entries into foreign markets, subsequent expansion in a particular market, or an increased level of internationalization of the MNE. Constraints are theoretically grounded factors that impede the growth of MNEs, including those that deter the entry to and expansion in host countries and those that lead to exits from or divestments in host countries. In addition, our review reveals that certain factors moderate the effects of facilitators and constraints, and we report these findings in the sections on facilitators and constraints. Given that we review the growth of MNEs through a Penrosean lens, we conclude each subsection with a discussion of Penrose’s insights into the research findings related to MNEs’ growth. Figure 2 shows a conceptual diagram for determinants (including facilitators, constraints, and moderators) of the growth of MNEs.

Facilitators of MNE Growth

Several mainstream IB theories have offered key theoretical insights concerning the facilitators of the growth of MNEs. The internalization theory of FDI explains the existence of multinational firms, and it maintains that firm-specific advantages, the transfer of which involves high transaction costs, facilitate the growth of firms in foreign markets (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Hennart, 1982; Rugman 1981). Internationalization process theory, which has its roots in Penrose’s theory of the firm, suggests that experiential learning of knowledge about the host country increases a firm’s commitments in pursuing growth in the host country (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). Recent research on emerging-economy MNEs (EMNEs) suggests that resource deficiency at home motivates these firms to seek strategic assets in advanced economies (Luo & Tung, 2007; Makino, Lau, & Yeh, 2002).

In our review, we find that factors that facilitate the growth of MNEs can be categorized broadly into the following categories, i.e., underutilized firm-specific resources, managerial resources, experiential learning, and external drivers. Concerning the facilitators of growth, not all research on the growth of MNEs draws explicitly on Penrose’s theory, but this research is consistent with Penrose’s theory in that it focuses on under-utilized, firm-specific resources, managerial resources, and experiential learning as key drivers of the growth of the firm. In terms of the fourth facilitator, i.e., external drivers, the two lines of research differ in how they view the role of external conditions. Penrose suggests that managers perceive and interpret market conditions subjectively; hence, markets are ‘created.’ She focuses on purposeful internal drivers of growth (i.e., endogenous growth), and attributes the lack of growth opportunities to weak entrepreneurial capabilities and/or a lack of impregnable resource bases in the firm. In contrast, many studies of the growth of MNEs have attributed a firm’s international growth primarily to external conditions. From a Penrosean perspective, the fact that favorable conditions in the host market encourage a firm to expand indicates that its managers are aware of market conditions and are capable of responding to them. Thus, knowledge of these market conditions and the vision of how to penetrate such markets are understood as part of the firm’s entrepreneurial capabilities. Below we report findings from our review concerning the effects of the four key facilitators on the growth of MNEs. Table 1 summarizes these findings.

Firm-specific resources

Internationalization theory (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Hennart, 1982; Rugman, 1981) views firm-specific resources, especially those that are intangible, as the main reason firms pursue international growth because the economic value of such resources does not depreciate through use. Since these resources constantly are underutilized (Caves, 1971), managers are motivated to pursue further exploitation in foreign markets. Given that intangible resources are fraught with contractual hazards and incur substantial costs when exchanged in the market, it often is relatively cost-efficient for firms to exploit them through FDI rather than through market mechanisms. Thus, the exploitation of firm-specific intangible resources largely explains the emergence of MNEs and their growth in foreign markets. In addition, firm-specific intangible resources often are proprietary, resist imitation (Chi, 1994), and provide monopolistic advantages that enable MNEs to overcome the liability of foreignness (Hymer, 1960). These resources enable firms to outcompete rival firms in foreign markets, and achieve and sustain profitable growth. Classic examples of firm-specific intangible resources shown to facilitate the growth of MNEs include technological knowledge and marketing knowledge (Chang, 1995; Delios & Beamish, 1999; Hennart & Park, 1994; Tan & Vertinsky, 1996; Tseng, Tansuhaj, Hallagan, & McCullough, 2007). A meta-analysis (Kirca et al., 2011) reports that technological knowledge has a more significant positive effect on the internationalization of firms than does marketing knowledge. R&D activities help generate a continuous stream of new products and enable firms to maintain competitiveness and profitability when pursuing growth in global markets (Buckley & Casson, 2007). Firm-specific resources include production-related proprietary resources as well as “an organizational capability to efficiently coordinate and control the MNEs’ asset base” (Rugman & Verbeke, 2001: 238). An example, documented by Pedersen and Shaver (2011), is firm-specific management infrastructure for international expansion, which has natural economies of scale that promote further international growth.

Exploiting firm-specific intangible resources requires a firm to transfer or replicate resources in foreign operations (Teece, 1977). The costs of transferring intangible resources increase with the tacitness of resources (Kogut & Zander, 1992; Teece, 1981). Martin and Salomon (2003) show that the tacitness of a firm’s technology has an inverted U-shaped relationship with the likelihood of a firm choosing FDI, which suggests that even though technology assets in general encourage international growth, the cost of transferring highly tacit technology can hamper a firm’s growth in foreign markets. In addition, the (limited) fungibility of resources across national borders influences international growth. Some of the intangible resources of the firm might be valuable for all regions (i.e., non-location-bound), while others may be relevant only for certain regions or countries (i.e., location-bound) (Rugman & Verbeke, 1992, 2004). Location-bound resources inhibit the firm’s growth in other locations (Mauri, Song, & de Figueiredo, 2017).

Firm-specific resources may lose value not only in different geographical locations but also in changing environments. Therefore, MNEs must develop dynamic capabilities to adapt to changing environments (Luo, 2000; Pitelis & Teece, 2010; Teece, 2007, 2014; Teece et al., 1997). Vahlne and Ivarsson (2014) propose that the dynamic capabilities of MNEs might consist of their entrepreneurial ability and transformational leadership to identify and implement growth opportunities (Teece, 2007, 2014), networking capability (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009), technology development capability (Buckley & Casson, 2007; Dunning & Lundan, 2008), and the capacity to develop knowledge on managing foreign operations. Research on MNE growth also emphasizes operational flexibility (Chi, Li, Trigeorgis, & Tsekrekos, 2019), which is associated with the ability of firms to relocate sourcing, production, or distribution activities from one geographical location to another in short time-periods when facing environmental changes. Further, international expansion can be viewed as a mechanism through which firms can renew their firm-specific resources through (1) their interaction with foreign environments (Cantwell, 1989, 2009; Dunning, 1979; Pitelis & Teece, 2010; Rugman & Verbeke, 1992, 2001), (2) acquiring new strategic assets in advanced economies (Luo & Tung, 2007), and (3) leveraging subsidiaries’ initiatives (Birkinshaw, 1997; Birkinshaw & Hood, 1998). Finally, foreign subsidiaries can play an important role in shaping the overall capabilities of MNEs (Birkinshaw, 1997; Cantwell & Mudambi, 2005), but, in our sample, only two empirical studies (Kafouros & Aliyev, 2016; Lee, Chung, & Beamish, 2019) focus on resources at the subsidiary level.

In summary, research concerning the growth of MNEs has provided ample evidence for the materiality of the firm-specific (especially intangible) resources for expansion of firms into foreign markets. The value to be derived from firm-specific intangible resources depends on the degree of tacitness, fungibility, and adapt-ability of those resources. It is noted that the research streams on the growth of MNEs and on Penrose (1959) consider underutilized, firm-specific resources as the basis on which firms can expand into new geographical or product markets. For research on the growth of MNEs, resources are underutilized primarily because of their intangible nature, whereas, in Penrose’s theory, resources are underutilized due to the indivisibility of assets, fungibility, and continuous managerial learning about resources. In terms of enablers of long-term, profitable growth, the research on MNE growth emphasizes the dynamic capabilities and operating flexibility that help firms adapt to changing technological, economic, and institutional environments. Also, this research considers international expansion as an opportunity to adapt and strengthen firm-specific resources. Similarly, Penrose emphasizes the capability to build versatile and impregnable (technological) “bases” (1959: 137) that enables the pursuit of growth via (related) product diversification (Buckley & Casson, 2007), which creates a virtuous cycle of ‘resource learning’ and innovation.

Managerial resources

Research on the growth of MNEs has shown that managers have a key role in orchestrating the growth of their firms. In addition to Penrose’s growth theory, this research draws on upper echelon theory, agency-theoretic corporate governance, and internationalization process theory, and it focuses on managerial attributes and governance conditions that shape managerial incentives and capabilities to formulate or implement international growth strategies.

An extensively examined managerial attribute is international work experience, which, in theory, enhances managers’ awareness of promising international business opportunities and effective implementation of international expansion. Empirical research has corroborated that MNEs whose managers have greater international experience achieve a higher level of internationalization (Athanassiou & Nigh, 2002; Carpenter & Fredrickson, 2001; Chen, Chang, & Hsu, 2017; Nielsen, 2010; Sambharya, 1996). However, case-study research indicates that an imprinting effect of prior international experience may reduce managerial motivation to learn, which can have a negative effect on the long-term growth of the firm (Bingham & Davis, 2012). Other managerial attributes, such as industry experience and elite education, also are shown to facilitate international growth (Chen et al., 2017; Tihanyi, Ellstrand, Daily, & Dalton, 2000).

In addition to managerial experience, managers’ network connections also are an important driver for identifying opportunities for profitable international growth (Johanson & Vahlne, 2006, 2009). Managerial connections can be particularly useful when MNEs seek to penetrate a foreign market. For example, managers’ cooperative relationships with local and central governments in host countries provide firms with preferential access to scarce resources, such as permits and licenses, resulting in higher subsidiary growth (Luo, 2001). Co-ethnic networks in one location of the host country increase the likelihood of subsequent investment in other co-ethnic locations, and they accelerate the overall pace of growth in the host country (Stallkamp, Pinkham, Schotter, & Buchel, 2018). However, managerial connections also might constrain growth opportunities in terms of the geographical locations that managers favor due to close ties and/or prior experience (Musteen, Francis, & Datta, 2010). Similarly, home country network connections tend to promote domestic growth at the expense of international expansion (Bai, Chen, & He, 2019; Fernández-Méndez, García-Canal, & Guillén, 2018; Iurkov & Benito, 2018). Overall, international diversity is the type of managerial connection that leads to long-term international growth (Hagen & Zucchella, 2014; Stoian, Dimitratos, & Plakoyiannaki, 2018).

Given that managers work collectively as a team, the composition of the management team matters. Top management team (TMT) diversity, which implies heterogeneity in experience, skills, and viewpoints, can facilitate the exploration of new growth opportunities in foreign markets. TMT diversity is shown to increase the novelty of FDI locations (Barkema & Shvyrkov, 2007), but the link between the diversity of the TMT and the growth of MNEs remains unclear. Some empirical studies find a positive association between the growth of MNEs and the diversity of the TMT’s international experience (Sambharya, 1996), education (Carpenter & Fredrickson, 2001), and firm/team tenure (Carpenter & Fredrickson, 2001; Tihanyi et al., 2000), but other research studies fail to find such associations (Barkema & Shvyrkov, 2007). It may be that too much diversity on a team can lead to difficulties in reaching consensus when making decisions, thereby hampering international growth. Yet, few attempts are made to test the curvilinear relationship between the growth of MNEs and the diversity of the TMT, and those attempts lack empirical support (Carpenter & Fredrickson, 2001).

Several research studies have utilized the upper echelon theory, the corporate governance literature, and information processing theory to examine the managerial characteristics or corporate governance mechanisms that influence managers’ incentives to pursue growth in risky international markets. Narcissistic CEOs tend to be aggressive and have more confidence in pursuing international growth (Agnihotri & Bhattacharya, 2019). A young and elitely educated TMT or a large board expands a firm’s information processing capacity, and increases managers’ willingness to assume risk and undertake international expansion (Hitt, Tihanyi, Miller, & Connelly, 2006b; Singh & Delios, 2017; Tihanyi et al., 2000). Outside directors and institutional investors (such as mutual funds or pension funds) can assist managers in identifying international opportunities and thus promote international expansion (Majocchi & Strange, 2012; Tihanyi, Johnson, Hoskisson, & Hitt, 2003). CEO duality, which agency theory predicts to be an undesirable board leadership structure, is found to be linked positively with international expansion because CEO duality can serve as unified leadership and expedite decision-making (Singh & Delios, 2017). Similarly, CEOs who are owners of the firms have the power to take on strategic decisions, including undertaking international expansion (Chittor, Aulakh, & Ray, 2019). In addition, contingent pay and firm-level resource slack increase managerial incentives to seek new international growth opportunities (Dagnino, Giachetti, La Rocca, & Picone, 2019; Lin, 2014, Tihanyi, Hoskisson, Johnson, & Wan, 2009). Similarly, in state-owned enterprises (SOEs), soft-budget constraints and long-term investment horizons can encourage managers to take on risky projects, such as international investments (Rudy, Miller, & Wang, 2016), especially when the governance framework in the country curtails SOE managers’ pursuits for private benefits (Estrin, Meyer, Nielsen & Nielsen, 2016) or even sets goals for SOEs to pursue international growth (Mariotti & Marzano, 2019). On the negative side, top managers’ inertia and unwillingness to take risk inhibit decisions to expand into foreign markets (Dow, Liesch, & Welch, 2018).

Several studies have drawn on the research literature on expatriate managers (Boyacigiller, 1990; Edström & Galbraith, 1977) and Penrose (1959) to examine the utilization of expatriates on subsidiary growth. Given that expatriate managers serve as knowledge transfer and coordinating mechanisms between the headquarters (HQ) of the MNEs and their subsidiaries, multinational firms that send more expatriates (most of whom are managers) to their subsidiaries in initial periods and those who replace expatriates with foreign personnel at a slower rate achieve higher growth rates over time. Essentially, these firms are better able to transfer knowledge (Kawai & Chung, 2019) and to train and integrate the new members in their subsidiaries (Riaz, Rowe, & Beamish, 2014; Tan & Mahoney, 2007).

Note that the empirical results reviewed in this section are based on the managers at the HQs of the MNEs. However, subsidiary initiatives are an important part of corporate entrepreneurship that can drive the growth of MNEs in foreign markets (Birkinshaw, 1997). Thus, additional empirical research is needed to examine how subsidiary managers influence the overall growth of MNEs.

Overall, the extant growth research of MNEs on managerial resources has focused primarily focused on managerial attributes and governance conditions that might affect managerial incentives and capabilities to formulate and implement international growth strategies as opposed to firm-specific managerial capabilities in maintaining coordination within MNEs, which receives central attention in Penrose’s growth theory. Given that an MNE consists of a group of geographically dispersed, goal-disparate organizations (Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1990), maintaining internal coordination and control within the MNE involves challenging managerial problems, such as potential conflicts and the incongruence of goals between the HQ and the foreign operations (Nohria & Ghoshal, 1994; Verbeke & Yuan, 2005). Thus, whether and how firm-specific managerial experience at the HQs of MNEs enhances the management of foreign operations and facilitates growth is likely a worthy research direction.

Recent developments in the dynamic capabilities approach (Teece, 2014) and dynamic managerial capabilities (Adner & Helfat, 2003; Helfat & Martin, 2015) have emphasized the entrepreneurial qualities of the TMT as a key factor in sustaining long-term competitive advantages in global markets. Our review suggests that the diversity of the experiences of the TMT might contribute to such qualities. More research is needed to understand what constitutes the entrepreneurial capabilities of MNEs that facilitate continued entries into new foreign markets.

Experiential learning

The growth of MNEs requires general knowledge of international management and market-specific knowledge, much of which is less structured and gained mainly through experience (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). Internationalization process theory (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 1990) suggests that experiential learning enables managers to recognize growth opportunities better, and reduces the perceived risk associated with growth, thereby increasing commitments in foreign markets. Experiential learning takes the form of direct learning and indirect learning (i.e., learning from the experience of other people) (Bingham & Davis, 2012). Extant research has drawn on internationalization process theory, organizational learning literature, and the behavioral theory of the firm to examine the impact of both types of learning on the growth of MNEs. In terms of direct learning, a firm’s experience in international activities increases the speed of its overall international expansion (Hutzschenreuter, Kleindienst, Guenther, & Hammes, 2016), but its impact is decreased when the firm already has host-country experience (Henisz & Delios, 2001). The transferability of general international experience to a particular subsidiary is also reduced when the cultural context of the subsidiary is more distant from the cultures in which the firm has accumulated experience (Barkema, Bell, & Pennings, 1996). In addition, the geographical makeup of a firm’s international activities makes a difference. Specifically, the depth of international activities (as reflected by a firm’s experience in a certain host country) has an inverted U-shaped relationship with the speed of international expansion (Casillas & Moreno-Menendez, 2014). This outcome occurs because, even though it is easier for firms to expand in markets where they already have experience, opportunities for further learning are limited in such markets. The impact of the diversity of international activities (i.e., host-country dispersion) on growth is found to be mixed (i.e., direct positive and indirect negative effects). A high level of international diversity enables firms to accumulate extensive knowledge of the markets, which supports international growth in the long term (Casillas & Moreno-Menendez, 2014; Nachum & Song, 2011; Zhou & Guillén, 2015). However, high international diversity also creates coordination costs (Schu, Morschett, & Swoboda, 2016) and information overload that impedes technological learning, which has an indirect negative effect on international growth (Zahra, Ireland, & Hitt, 2000).

Market-specific experience matters when it comes to international growth. Research shows that experience in the host country increases a firm’s sales growth in that market (Luo, 1999) and reduces the exit rate in both the host country (Delios & Beamish, 2001; Gaur & Lu, 2007; Li, 1995) and other countries with similar institutional environments (Perkins, 2014). The positive effect of host-country experience on growth is even greater in countries in which the quality of institutions is poor (Lu, Liu, Wright, & Filatochev, 2014). However, once exiting from a host country, the experience the firm accumulated during its stay in that country has no impact on the firm’s further decisions in that country (Surdu, Mellahi, & Glaister, 2019). Moreover, experiential learning at home is found to contribute to international growth. A firm’s experience with a certain technology in its home country can reduce the cost of transferring the technology to foreign operations, thereby enabling greater international growth (Martin & Salomon, 2003). Firms with substantial experience in making domestic and foreign acquisitions have built and refined acquisition routines that facilitate the firm’s international growth through acquisitions (Nadolska & Barkema, 2007). Similarly, a firm’s domestic dispersion enables the firm to develop capabilities to coordinate remote business units, which can subsequently be used to support international growth (Santangelo & Stucchi, 2018). Finally, a firm’s prior experience of inward internationalization at home, such as export and original equipment manufacturing activities, nurtures its international management capabilities and enables faster international growth (Luo & Bu, 2018).

In addition to direct experiential learning, indirect learning also can facilitate international growth. Observing or interacting with other firms that have experience in the host country enables a firm to gain knowledge and information that help to reduce uncertainty about the host country. Research shows that firms can achieve greater international growth and a lower exit rate if they have foreign alliance partners (Cesinger, Hughes, Mensching, Bouncken, Fredrich, & Kraus, 2016; Hong & Lee, 2015), interlocking partners (Xia, Ma, Tong, & Li, 2018), and inward international activities (Li, Li, & Shapiro, 2012; Li, Yi, & Cui, 2017), as well as following a shared industry recipe (Monaghan & Tippmann, 2018). Firms also can obtain information spillover from other firms (Henisz & Delios, 2001; Shaver, Mitchell, & Yeung, 1997), such as other firms from the same country of origin (Hernandez, 2014; Tan & Meyer, 2011) unless agglomeration with other firms creates a knowledge leakage hazard that threatens survival (Mariotti, Mosconi, & Piscitello, 2019; Shaver & Flyer, 2000). Although these different sources of external experiential knowledge all make positive contributions to international growth, their relative impacts might be different. For example, prior acquisition experience of a firm’s interlocking partners has a greater impact on the growth of MNEs than that of joint venture partners (Xia et al., 2018). In addition, intra-MNE networks or business groups can be a reservoir for learning (Eriksson, Johanson, Majkgård, & Sharma, 1997). Subsidiaries achieve greater growth by learning from strategic decisions of the intra-MNE network (Banerji & Sambharya, 1996; Gaur, Kumar, & Singh, 2014; Gaur & Lu, 2007; Guillén, 2003; Kim, Lu, & Rhee, 2012). The learning opportunities within the intra-MNE networks are greater in the presence of diversity. For example, a subsidiary’s learning from its sister subsidiaries yields more non-redundant knowledge if they are from different entry cohorts (Kim et al., 2012).

Research has indicated that direct learning and indirect learning are alternative sources of knowledge about foreign markets. Firms with direct experience are less influenced by other firms’ experience in making their decisions concerning international expansion (Gupta & Misangyi, 2018; Henisz & Delios, 2001). Similarly, in the presence of indirect learning, direct experience is less influential on the firm’s international growth (Cui, Li, Meyer, & Li, 2015; Hutzschenreuter et al., 2016). Even so, empirical evidence shows that direct learning can be supportive of indirect learning by enhancing a firm’s ability to absorb knowledge from other firms. For example, Kim et al. (2012) report that the prior experience of sister subsidiaries can reduce the exit rate of a subsidiary more effectively when the parent has experience in the host country or general international experience. In sum, direct and indirect sources of learning have been found to be substitutive, but these sources of learning also can be complementary and reinforcing. These substitution and synergistic effects constitute a fertile ground for future empirical studies.

Overall, MNE growth research and Penrose’s theory are similar in that they indicate that growth can be generated internally through experiential learning. Penrose’s growth theory suggests that the process of learning-by-doing that occurs within a firm generates new knowledge for further utilization. The research on the growth of MNEs corroborates that experiential learning through international expansion enables a firm to accumulate knowledge concerning the host country (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 1990), combine locational advantages with its own resources (Dunning, 1993), and locally adapt their firm-specific advantages (Rugman & Verbeke, 2001). Yet, there is a notable difference between the two approaches when it comes to the main objects of learning. Penrose focuses on (direct) firm-specific learning that facilitates the integration of new knowledge and enhances the coordination of the complex (i.e., internationally diversified) organization. In contrast, much of the MNE growth research focuses singularly on the need to address differences in foreign markets, and thus pays attention to any learning (direct or indirect) that provides knowledge about foreign markets (Steen & Liesch, 2007). Other streams of research in the IB literature have substantial discussions on maintaining integration within MNEs (e.g., O’Donnell, 2000; Prahalad & Doz, 1987), but most do not connect the notion of administrative coordination to the growth of MNEs.

External drivers

Extant research has drawn on emerging economy research and institutional economics to examine a wide range of host and home country-level conditions that drive a firm’s profitable growth in international markets. Empirical studies have shown that improved conditions in the host country, such as high demand growth, pro-market reform, market-supporting institutions and infrastructure, and regulatory support from the country’s governments, enhance the survival and growth of subsidiaries in the host country (Belderbos & Zou, 2007; Dau, 2012; Dunning & Kundu, 1995; Guler & Guillén, 2010a; Liao & Yu, 2012; Paul & Wooster, 2008; Surdu et al., 2018; Surdu, Mellahi, Glaister, & Nardella, 2019; Tschoegl, 2002; Van Den Bulcke, Zhang & Li, 1999). Support from home governments also can facilitate the international expansion of firms (Finchelstein, 2017; Gaur, Ma, & Ding, 2018). In addition, a firm’s international growth can be an outcome of its attempt to escape unfavorable conditions at home, such as having a small home market (Lindqvist, 1991), poor protection of investors and a limited market for external capital (Li & Yue, 2008), corruption (Bertrand, Betschinger, & Laamanen, 2019), and institutional uncertainty and turbulence (Fathallah, Branzei, & Schaan, 2018; Shi, Sun, Yan, & Zhu, 2017), especially for young and non-group affiliated firms that have substantial disadvantages at home (Kumar, Singh, Purkayastha, Popli, & Gaur, 2020). In particular, home-based scarcity of advanced technology motivates the expansion of EMNEs into advanced countries so they can acquire advanced technological knowledge (Gaur et al., 2018; Luo & Tung, 2007). However, inward FDI activities in the EMNEs’ home countries might provide similar benefits and reduce such a propensity (Li et al., 2012, 2017). Expanding into more advanced countries gives EMNEs access to strategic resources (Luo & Tung, 2007; Madhok & Keyhani, 2012; Young, Huang, & McDermott, 1996) and facilitates organizational change in the EMNEs (Kalasin, Dussauge, & Rivera-Santos, 2014). Then, with stronger competitive positioning, these firms can pursue sequential expansion in global markets.

A wide spectrum of competitive and cooperative conditions in the industry can shape the growth of MNEs. Early FDI research shows that a firm’s international expansion can be an oligopolistic reaction to domestic competitors (i.e., follow-the-leader) or foreign competitors (exchange-of-hostage) (Flowers, 1976; Hennart & Park, 1994; Knickerbocker, 1973; Yu & Ito, 1988). Studies that are more recent have corroborated that firms are more likely to expand in a host market as a response to foreign competitors (Hutzschenreuter & Gröne, 2009; Ito & Rose, 2002). Firms also follow their domestic competitors’ FDI moves (Guillén, 2002; Li, Xia, Shapiro, & Lin, 2018), but they only do so when they have a large or comparable market share compared to their competitors in domestic markets (Gimeno, Hoskisson, Beal, & Wan, 2005). In addition, firms are less likely to follow either foreign or domestic competitors to enter a host market when competition in the market is intense (Chan, Makino, & Isobe, 2006; Martin, Swaminathan, & Mitchell, 1998).

Empirical studies have reported that a firm’s expansion in foreign markets can be motivated by its domestic client’s entry into the host market (Martin et al., 1998). Firms that occupy central positions in home networks are in a better position to attract exchange partners, which facilitates their expansion into foreign markets (Guler & Guillén, 2010b). When MNEs are early entrants into a host market, they tend to capture early mover advantages over competitors and achieve greater sales growth (Luo, 1998). Industries that are rapidly globalizing also push firms to expand their foreign activities to achieve economies of scale and scope so they can remain competitive with their global rivals (Chang & Rosenzweig, 1998).

Overall, research has shown that host and home country-level and industry-level conditions have significant effects on a firm’s profitable growth in international markets. From a Penrosean perspective, the fact that these external conditions encourage a firm to expand indicates that its managers are aware of market conditions and are capable of responding to them. Thus, knowledge of these external conditions and the ambition to penetrate the foreign markets constitute part of the firm’s entrepreneurial capabilities.

Relationships between facilitators

Penrose’s theory and the research on the growth of MNEs take slightly different approaches to theorizing the relationships among facilitators. In Penrose’s theory, the three main facilitators, i.e., firm-specific resources, managerial resources, and experiential learning, are interrelated and have their roots in the conceptualization of the firm. Penrose (1959) considers a firm as an administrative unit and a collection of productive resources, the disposal of which is determined by managers’ decisions. Managerial firm-specific learning results in an increase in managers’ knowledge and understanding about firms and their resources, which, in turn, increases the services available from those resources. Accordingly, Penrose predicts positive interactive effects between managerial firm-specific learning and resources. In comparison, in much of the MNE research, the growth effects of underutilized firm-specific resources, managers, and experiential learning are examined separately. The conceptualization of the firm typically is not used to derive the sources of facilitators of the growth of MNEs or to examine the interrelationships among them. Even so, our review of the research indicated that facilitators interact to make impacts on the growth of the MNEs. For example, managerial experience and the managers’ connections with clients have a synergic effect on a firm’s level of internationalization because experience enables managers to exploit their connections more effectively (Hitt, Bierman, Uhlenbruck, & Shimizu, 2006a). International experience makes unfavorable conditions at home a stronger motivator for international growth (Gaur et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2017). International experience also increases the tendency of a firm to follow its clients (Qian & Delios, 2008), but it decreases the firm’s likelihood of matching its peers’ entry into foreign markets (Gupta & Misangyi, 2018). In terms of experiential learning, managerial characteristics and external conditions can influence how firms/managers learn. For example, narcissistic CEOs rely more on direct learning rather than indirect learning (Zhu & Chen, 2015). The Internet might speed up experiential learning and facilitate international expansion (Petersen, Welch, & Liesch, 2002), especially for firms with prior international experience (Rhee, 2005). In summary, we have preliminary empirical evidence of interactions among the key facilitators of growth. However, more studies are needed to provide a theoretically grounded, empirical examination on how all four facilitators interact to influence the growth of MNEs.

Constraints on MNE Growth

Several research streams have provided insights concerning what constrains the growth of MNEs. Monopolistic advantage theory (Hymer, 1976) and research on the liability of foreignness (Zaheer, 1995) contend that MNEs incur additional costs when doing business abroad. The integration-responsiveness framework, which elaborates on the contingent strategies of MNEs based on their organizational setting (Prahalad & Doz, 1987), underscores the importance of adapting to host-country differences while maintaining internal coordination. Research on cross-cultural management (Hofstede, 1984) and emerging economies (Hoskisson, Eden, Lau, & Wright, 2000) also recognizes the challenges for MNEs in dealing with cross-country differences in cultural and institutional environments. Our review of the research on the growth of MNEs indicated that many of the studies focused on cross-country differences and risk/uncertainty, which are related to external conditions for MNEs. There are also studies that examined internal constraints, such as financial and managerial constraints, with the latter drawing explicitly on Penrose’s growth theory. Penrose does not consider external conditions as serious barriers to growth, and she attributes any inability of a firm to alleviate external constraints to its insufficient managerial capabilities. Thus, Penrose would predict that managerial attributes/actions moderate (e.g., alleviate the negative) impact of external constraints on growth. This logic is consistent with many of the studies that discuss the conditions and strategies (managerial choices) that are likely to moderate the impacts of the external constraints on the growth of the MNEs. Below, we report the findings of these studies, which are summarized in Table 2.

Cross-country differences

Cross-country differences in terms of cultures, institutional conditions, and economic development increase a firm’s knowledge gaps in host countries, create difficulties in transferring firm-specific resources and in building legitimacy (Ghemawat, 2001; Xu & Shenkar, 2002), thus creating extra costs of doing business (Cuervo-Cazurra, Maloney, & Manrakhan, 2007) and the liability of foreignness (Mata & Freitas, 2012; Qian, Li, & Rugman, 2013; Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997). As a result, firms might withhold their resource commitment to such host countries (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 1990). Empirical evidence suggests that, in general, cross-country differences inhibit market entry (Berry, Guillén, & Zhou, 2010), reduce the speed of expansion (Hutzschenreuter et al., 2011; Schu et al., 2016), and result in an exit from the host country (Demirbag, Apaydin, & Tatoglu, 2011; Kang, Lee, & Ghauri, 2017). These studies also show that cross-country distances have differential effects on firms. For example, the negative impact of cultural distance on the longevity of subsidiaries has been found to be stronger for joint ventures and acquisitions than for wholly owned investments and greenfield investments because the former modes require MNEs to accommodate both host-country and corporate cultures of the target subsidiaries (Barkema et al., 1996). The negative impacts of cultural distance on the growth of MNEs also are stronger for larger and older firms because these firms tend to be bureaucratic and rigid, and they have difficulties in adapting to culturally distant host countries (Li, Zhang, & Shi, 2020). Cross-country differences typically take the form of the Euclidean or Mahalanobis distance between home and host countries. However, given that a firm’s stock of foreign market knowledge expands when it grows into different foreign locations, the concept of cross-country distance can be dynamic and firm-specific. Zhou and Guillén (2015) show that a firm’s foreign location portfolio, or “home base,” can better predict its foreign market entry than its home country.

Early FDI theories posit that the liability of foreignness might be alleviated if MNEs possess monopolistic advantages (Dunning, 1980; Hymer, 1976). Empirical evidence has corroborated that a firm’s technological capabilities reduce the negative impact of cross-country distance on the exit of its subsidiary (Kang et al., 2017). Yet, Xu and Shenkar (2002) propose that MNEs with strong firm-specific, routine-based, competitive advantages might be more vulnerable to normative institutional distances, because such firms tend to impose their own institutional norms and rules on foreign subsidiaries, and, thus, they are likely to find it costly to do so in host countries that are normatively distant.

Given that cross-country differences create a firm’s knowledge gap, host-country experience should help to reduce the gap and the negative impact of cross-country differences (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 1990). Indeed, cross-country differences are more strongly linked to the exits of the subsidiaries of MNEs that do not have experience in the host countries (Berry et al., 2010). However, research shows that the moderating effects of host-country experiences might be complex. Zeng, Shenkar, Lee, and Song (2013a) report that, at low levels, host-culture experience increases the mortality of subsidiaries in the host country until the MNEs have made four or more investments in the host culture. Moreover, Zeng, Shenkar, Song, and Lee (2013b) report similar empirical results for the growth of firms with limited (general) international experience in culturally dissimilar countries. Thus, it is likely that low levels of experience increase the propensity of the firms to make erroneous inferences from their experience.

In general, cross-country differences are viewed as a source of complexity and additional costs, but these differences can provide MNEs with arbitrage opportunities (Ghemawat, 2007; Nachum & Song, 2011), and empirical evidence corroborates this view. For example, Tsang and Yip (2007) find that the exit rates of subsidiaries are lower in both economically less-developed countries and more developed countries (as opposed to moderately developed countries), because such variance provides opportunities for MNEs to explore or exploit the economic differences. Arregle, Miller, Hitt, and Beamish (2016) show that a moderate level of institutional diversity within a region enables firms to arbitrage institutional differences across countries within the region, but institutional diversity at high levels can create managerial and organizational problems for MNEs. In addition, cross-country differences can provide learning opportunities for the MNE as a whole. Two meta-analyses find that, even though cultural distance influences an MNE’s entry and exit in a host country, it does not diminish its overall performance and the extent of its internationalization as a whole (Beugelsdijk, Kostova, Kunst, Spadafora, & van Essen, 2018; Tihanyi, Griffith, & Russell, 2005). Such empirical findings suggest that operating in culturally different countries might provide potential learning benefits for the entire MNE. Indeed, Zeng et al., (2013a) report that prior experience in dissimilar cultures improved the ability of the firm to generalize and apply its learning to a distant culture, resulting in reduced mortality of its subsidiaries.

Risk and uncertainty in host countries

Risk and uncertainty make it difficult for firms to assess the economic value of their investments in the host countries and hence deter entry. Once investments are made, unexpected events can change the payoff prospect of investments and increase the likelihood of divestments. Economics literature and the real options literature distinguish between endogenous and exogenous uncertainty (Bowman & Hurry, 1993; Dixit & Pindyck, 1994; Folta, 1998). Endogenous uncertainty arises from insufficient knowledge about foreign markets, and it can be mitigated by the acquisition of knowledge about the markets through direct or indirect learning (Buckley, Chen, Clegg, & Voss, 2020; Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 1990) or by a real options approach in investment strategies, which can be applied to equity joint ventures (Kogut, 1991). Exogenous uncertainty is unaffected by the firm’s actions and is typically reduced over time.

Our review finds that host-country uncertainty leads to slower growth as manifested by modest, incremental investments (Delios & Henisz, 2003a, 2003b; Rhee & Cheng, 2002) and delayed entry (Gaba, Pan, & Ungson, 2002). Research also has examined exogenous uncertainty in a variety of forms, including political hazards (Dai, Eden, & Beamish, 2013; Fernández-Méndez, García-Canal, & Guillén, 2019; Henisz & Delios, 2001; Zhong, Lin, Gao, & Yang, 2019), institutional weakness (Dhanaraj & Beamish, 2009; Getachew & Beamish, 2017; Sartor & Beamish, 2020), the fluctuation of exchange rates and labor costs (Fisch & Zschoche, 2012; Song, 2014, 2015), economic crises (Belderbos & Zou, 2009; Chung, Lee, Beamish, & Isobe, 2010; Chung, Lee, & Lee, 2013), and discontinuous shocks, such as war, terrorist attacks, natural disasters, and technological shutdowns (Dai, Eden, & Beamish, 2017; Oetzel & Oh, 2014; Pek, Oh, & Rivera, 2018). These forms of uncertainty are found to deter investments or to lead to an exit from the host country, but the overall effect of uncertainty is more prominent when the macroeconomic environmental change in the host country is highly correlated with other countries in which the MNE has operations (Belderbos & Zou, 2009). In addition, some forms of exogenous uncertainty have greater impacts than other forms. For example, Oh and Oetzel (2011) find that MNEs react more to technology disasters and terrorist attacks (via divestments) than they do to natural disasters. This outcome likely occurs because the impacts of the former types of disasters are more amplified socially.