Abstract

This paper examines the conditions under which foreign subsidiaries of multinational corporations (MNCs) are less prone to divestments. In the study, we examine the importance of foreign subsidiaries to MNCs based upon (1) product-level vertical integration, (2) human capital investments, and (3) technological investments in the subsidiaries. Given that we examine the probability that a subsidiary divestment will occur under the condition that all other subsidiaries are also at risk during the same time period, we employ a Cox proportional hazard rate model as a commonly used statistical method in the event history analysis. For empirical testing, we utilized a sample of Korean 439 MNCs and its 5306 foreign subsidiaries over a period of 1990–2011. We find that even under hostile host market demand conditions, MNCs are less likely to divest their foreign subsidiaries when those subsidiaries are vertically integrated with their headquarters, benefiting from a top management team dispatched from their headquarters or other affiliates, or possessing technological knowledge shared by their headquarters. These findings imply that relationship-specific investments with headquarters cause a hysteresis effect that deters these subsidiaries from being divested, even during times when divestments seem most likely because of unfriendly economic conditions in their host countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Divestments of the foreign subsidiaries of multinational corporations (MNCs) have long been of interest to international business researchers. MNCs’ sales or closures of their foreign businesses reflects the level of MNC performance (Bauer 2006; Lee and Madhavan 2010; Yan and Zeng 1999), changes in their global strategies, and changes to their cross-country management of foreign asset portfolios (Bauer 2006; Chow and Hamilton 1993; Kumar 2005). For this reason, subsidiary divestment decisions are at least as important as subsidiary establishment decisions. Given that foreign subsidiaries are exposed to a variety of macroeconomic uncertainties (e.g., adverse macroeconomic conditions in host countries), not all subsidiaries survive and thus MNCs have to be strategic in their subsidiary divestment decisions (Benito 2005; Hennart et al. 1998; Kumar 2005; Mata and Portugal 2000).

However, not all foreign subsidiaries are uniformly divested under the same host market conditions; some subsidiaries are long lived even in hostile host country situations. In particular, the literature on hysteresis argues that some environmental and organizational factors induce the hysteresis effect and thus retard MNCs’ divestment decisions. The notion of hysteresis indicates that certain deterrents make a firm less motivated to change its established choices even when situations change (Belderbos and Zou 2009; Bragger et al. 2003; Christophe 1997; Dixit 1989, 1992). The literature adopting this notion finds that certain environmental and organizational factors trigger a firm’s counterintuitive behavior to stick to its established investment even though changes in underlying causes for the past choice have invalidated it (Belderbos and Zou 2009; Christophe 1997; Dixit 1992; O’Brien and Folta 2009). Hence, in terms of subsidiary divestments, the hysteresis effect, heightened by certain environmental and organizational factors, increases organizational inertia and deters MNCs from abandoning their foreign subsidiaries even when they are exposed to hostile host market conditions.

The purposes of this study are twofold. First, taking the hysteresis perspective as a point of departure, we examine why MNCs do not abandon their foreign subsidiaries under hostile market conditions. Second, we investigate the organizational factors that explain subsidiary divestments. Compared with environmental and investment factors which are frequently examined in real options and/or sunk cost studies, organizational factors are under-researched. Further, the hysteresis effect, owing to the specific relationship between headquarters and their foreign subsidiaries, is a crucial but rarely examined phenomenon. Given that certain investments in foreign subsidiaries by parent MNCs reflects the strategic importance of those subsidiaries, it is thus important to examine whether the hysteresis effect reduces the divestment rates of MNC subsidiaries facing unfavorable market conditions in their host countries.

By using a dataset of Korean MNCs’ foreign subsidiaries, we examine both the environmental conditions of host countries and the nature of intra-firm connectedness between subsidiaries and their headquarters, the latter of which indicates each subsidiary’s level of strategic importance. Since the hysteresis perspective focuses on continued commitment to a current strategic position even under new hostile conditions, we first assess the impact of unfavorable economic conditions in the host country that trigger a subsidiary’s divestment. We next examine three contingent factors that reflect the level of importance of subsidiaries to their headquarters: (1) product-level vertical integration, (2) human capital investment, and (3) technological investment. We find that all independent variables show the expected impact on foreign subsidiaries’ divestments when exposed to declining market demand in their host countries, thereby supporting the hysteresis perspective.

2 Theory and Hypothesis Development

2.1 Subsidiary Divestments: The Hysteresis Effects of Relationship to Headquarters

For MNCs, foreign divestments are a challenging managerial issue given the decision requires the reversal of past diversification (Benito and Welch 1997; Haynes et al. 2003; Madura and Whyte 1990; Madura and Murdock 2012) and thus careful adjustments to international portfolios (Bauer 2006; Chow and Hamilton 1993; Kumar 2005). Aligning a firm’s international portfolio with its new asset and resource allocations can lead to increased firm performance and longevity. The foreign divestment literature finds that divestments of MNC foreign subsidiaries are caused by several internal and external factors. In particular, MNCs are exposed to a variety of external uncertainties including changes in exchange rates, demand, and institutions (Cuypers and Martin 2010). Unpredictable and uncontrollable changes in macroeconomic factors within and across countries incur a large cost burden, leading to low performance and eventually divetment (Belderbos and Zou 2009; Buckley and Casson 1998; Chung et al. 2010; Huchzermeier and Cohen 1996). If an MNC cannot either overcome these cost pressures or find new business opportunities from its foreign subsidiary exposed to hostile host market conditions, the firm is more likely to abandon the subsidiary of concern (Benito 2005; Hennart et al. 1998; Mata and Portugal 2000).

Contrary to the traditional perspective on subsidiary exits, however, foreign subsidiaries exposed to unfriendly host market conditions are not necessarily exited. As noted in the Introduction, the literature adopting the notion of hysteresis argues that certain environmental and organizational factors widen the “hysteresis band” in which a firm neither increases nor decreases its established investment (Bowman and Hurry 1993; Christophe 1997; Dixit 1992; O’Brien and Folta 2009). In other words, a firm delays its response to changes in the underlying cause and maintains its initial choice considering that the effects of a current input (or stimulus) persist (Dixit 1989, 1992; Oliva et al. 1988). The hysteresis effect indicates that certain conditions increase organizational inertia; therefore, firms will engage in counterintuitive behavior such as continued investment following negative feedback (Bragger et al. 2003; Dixit 1989, 1992; Oliva et al. 1988). Relevantly, Gaur and Lu (2007) argue that institutional unfamiliarity may give MNCs arbitrage benefits. Once a subsidiary is divested, the arbitrage benefits and learning attached to these benefits also dissipate, giving another reason for slow responses.

A common argument of hysteresis-based research in the area of divestment is that the specificity of an investment increases organizational inertia, thereby maintaining the investment in the longer run without divestment decisions changing significantly. In the international business context, considering that foreign subsidiaries’ operations are heavily dependent upon their headquarters’ support, relationship-specific investment between foreign subsidiaries and their headquarters is thus expected to affect hysteresis-driven organizational inertia. Such relationship-specific investment is affected by the governance structure related to the headquarters–subsidiary relationship. The specificity of foreign direct investment is more salient when foreign subsidiaries are controlled and managed by the headquarters. The greater the strategic importance of certain subsidiaries from the headquarters’ standpoints, the more they receive special care and a favorable allocation of physical, human, and intangible resources. Hence, foreign subsidiaries’ close ties with their headquarters can provide organizational slack and thus help them buffer against the environmental challenges associated with adverse host market conditions.

This close relationship between headquarters and foreign subsidiaries is observed among emerging market MNCs. Compared with MNCs from developed countries, MNCs from emerging markets or newly industrialized economies have a more headquarters-centered strategy based around vertical integration. Further, these MNCs have unique organizational cultures, which are embedded in business groups to address institutional voids. For example, compared with their counterparts in Japan, Samsung Electronics and LG Electronics, as two representative Korean MNCs, have more vertically integrated governance and owner family-centered control as the way of overcoming the institutional void in their home country.

Below, we first hypothesize the negative impacts of hostile host market conditions on subsidiary exits. We then hypothesize how three contingencies that represent the specific headquarters–foreign subsidiaries relationships affect reduced exit rates. In particular, we examine each subsidiary’s vertical integration with its headquarters and consider the impacts of the assigned top management team (TMT) and of shared technological knowledge. We predict that strong intra-firm connectedness based upon this relationship-specific investment is positively associated with the hysteresis effect and negatively related to subsidiary divestment.

2.2 Hostile Economic Conditions and Subsidiary Divestment

MNC foreign subsidiaries are exposed to diverse macroeconomic uncertainties and threats that affect their businesses in host countries (Chung et al. 2010; Cuypers and Martin 2010; Dai et al. 2013; Erramilli and D’Souza 1995). More specifically, the degrees and directionalities of changes in exchange rates, labor costs, market demand, and the institutional environment affect their input costs and output prices (Belderbos and Zou 2009; Fisch and Zschoche 2011; Kogut and Kulatilaka 1994; Miller and Folta 2002; Pantzalis et al. 2001), thus affecting the performance and longevity of these subsidiaries (Cuypers and Martin 2010; Dai et al. 2013; Kogut and Kulatilaka 1994).

For MNCs, the host country environment influences their production and sales in their target locations. For example, in favorable market situations, MNCs are more actively engaged in production and sales in their host countries. To exploit market opportunities, for example, they may increase their investment level (Fisch and Zschoche 2012; Lee and Song 2012). On the contrary, when a foreign subsidiary faces a hostile market environment in its host country, it may experience greater difficulty operating there, which increases its cost burden and requires strategic changes (Belderbos and Zou 2009; Buckley and Casson 1998; Fisch and Zschoche 2011; Kogut and Kulatilaka 1994). Since MNCs have a greater incentive to terminate these operations in light of their diminishing value, foreign subsidiaries subject to these adverse conditions are targets for divestment (Benito 2005; Fisch and Zschoche 2011; Hennart et al. 1998; Kumar, 2005; Mata and Portugal 2000).

In sum, an unfavorable host country market can negatively affect the subsidiary’s local production and sales, leading to losses and possibly short longevity. Given the high cost of MNCs managing subsidiaries in different countries, particularly those with unfavorable economic conditions, they are likely to reposition their international investment portfolios by abandoning subsidiaries.

2.3 Vertically-Integrated Subsidiary with Its Headquarters

The specificity of an investment may depend on the degree of headquarters integration. The function of a subsidiary at the production level determines whether it is strongly connected to the headquarters. At the production level, the impact of intra-firm connectedness on investment irreversibility and heightened hysteresis is reflected in the level of vertical integration among affiliated companies (Driver et al. 2010; Helper and Sako 2010; Kotabe and Murray 1990; Turnbull et al. 1992). Here, vertical integration is defined as the connection via the value chain activities of a product, thus reflecting the MNC’s global configuration (Hennart 2009; Masten et al. 1991).

Once a subsidiary is vertically integrated with its headquarters as part of the MNC’s production process, it may require careful deliberation by the headquarters as to whether it should disengage the subsidiary from the value chain activity, even in cases where the subsidiary is experiencing an unfavorable environmental change (Cho 1990; Driver et al. 2010; Helper and Sako 2010; Martin 1996). Such deliberation is necessary because when a link is missing in value chain activities, the impact does not stop at the specific subsidiary, but rather reaches the remaining value chain activities. For example, one Korean mobile phone maker manufactures the printed circuit boards for its mobile phones in its subsidiary in China. Without this component, the assembly plant in Korea would have great difficulty in producing the final cell phone product. As this example implies, reducing or even stopping the operations of a subsidiary may be challenging for the headquarters, even when the subsidiary is stricken by adverse market conditions in its host country. Under these circumstances, the subsidiary’s divestment decision is made by the parent firm rather than by the subsidiary itself.

Given that a subsidiary’s vertical integration with its headquarters is a relationship-specific investment that cannot be easily reversed, there may be heightened hysteresis and thus reduced subsidiary divestment even under adverse economic conditions when divestment might have otherwise occurred earlier (Cho 1990; Driver et al. 2010; Helper and Sako 2010; Martin 1996). If the subsidiary were divested, it would be costly for the MNC to restore the value chain. On the contrary, when a foreign subsidiary independently operates in a given host country with little interaction with its headquarters, it is likely to be divested when exposed to hostile macroeconomic conditions in its host country. Hence,

Hypothesis 1: Under hostile host market conditions, a subsidiary vertically integrated to its headquarters in high degree is less likely to be divested than those in low degree.

2.4 TMT Member Dispatched from the Headquarters

Nhoria and Ghoshal (1994, p. 492) argue that “[a]s the principal, the headquarters cannot effectively make all the decisions in the MNC since it does not possess and must, therefore, depend on the unique knowledge of subsidiaries. At the same time, the headquarters cannot relinquish all decision-rights to the subsidiaries since the local interests of subsidiaries may not always be aligned with those of the headquarters or the MNC as a whole.” Hence, the dilemma is how to make the best use of local knowledge while not losing control. In particular, when a subsidiary is important to the MNC, the headquarters must ensure that it does not lose control. In such a case, the coordinating role of expatriates becomes important. In addition, expatriates dispatched from the headquarters are more likely to have a single, global commitment to their headquarters, because they might already have internalized the headquarters-initiated MNC-wide shared values and common goals (Gong 2003; Gregersen and Black 1996; Kobrin 1988).

In this sense, the decision to dispatch expatriates from the headquarters is principally based on the notions of integrating subsidiary and headquarters operations and improving control and coordination in MNCs (Gaur et al. 2007). Among the many levels of expatriates, TMT members are best positioned to signal that the subsidiary is an important part of the MNC (Harzing 2001). Further, TMT members can make decisions on behalf of the headquarters. For this reason, the enhanced organizational inertia and hysteresis associated with a subsidiary’s importance to its headquarters are also tied to the level of an MNC’s commitment to sending their TMT members to subsidiaries (Luo 2002). Hence, dispatching a TMT member to a subsidiary clearly indicates the strategic importance of the focal subsidiary from the headquarters’ standpoint (Edström and Galbraith 1977; Edström and Lorange 1984; Forstenlechner and Mellahi 2011; Harzing 2001) and reflects the headquarters’ centralized strategy (Caligiuri and Colakuglu 2007).

This is especially true given the very high cost of sending a home country TMT member to a foreign subsidiary (Tarique et al. 2006). For this reason, foreign subsidiaries that have sent TMT members are likely to be actively managed and controlled by the headquarters compared with their counterparts without TMT members. In addition, since the future prospects of TMT members are mainly evaluated by the headquarters rather than by the subsidiaries, sending a TMT member to a subsidiary is a strong signal that the subsidiary is important to the headquarters (Bjorkman et al. 2004). For instance, the cases of two Korean Electronics echo this phenomenon. Specifically, the first company has dispatched Korean managing directors to all of its main manufacturing subsidiaries in China, while the second company has also dispatched TMT members to all its main manufacturing subsidiaries in India. Such actions have enhanced the significance of these subsidiaries and thus made it more difficult for the headquarters to abandon them, even in times of macroeconomic decline. Indeed, receiving a TMT member from the headquarters reflects the subsidiary’s importance to the achievement of its parent MNC’s global strategic objectives (Luo 2002). Hence,

Hypothesis 2: Under hostile host market conditions, a subsidiary having more TMT members from headquarters is less likely to be divested than those less.

2.5 Technological Knowledge Shared by the Headquarters

A subsidiary’s operation cannot easily be abandoned if its headquarters have transferred sufficient technological knowledge to make it a critical asset (Kim et al. 2012; Shane 1995). While technological knowledge assets in the form of tacit knowledge are critical for MNC success (Beret et al. 2003), they do not easily transfer (Dhanaraj et al. 2004; Jensen and Szulanski 2004). Indeed, Bjorkman et al. (2004, p. 447) argue that “knowledge transfer is carried out within the context of [the] interpersonal relationships” between headquarters and their subsidiaries.

The literature on knowledge transfer further argues that knowledge is “tacit” (Kogut and Zander 1993) and “sticky” (Szulanski 1996), indicating that knowledge transfer among companies is difficult and costly. The nature of inter-firm knowledge transfer requires a great deal of effort and time. Thus, headquarters’ investment in a subsidiary’s technological knowledge base becomes a relationship-specific investment that increases the irreversibility of the investment and hysteresis effect. In other words, greater technological knowledge transfer from the headquarters to its subsidiaries means a closer connection between these parties (Szulanski 1996; Tsai and Ghoshal 1998).

Dispatching engineers and R&D personnel from the headquarters to its subsidiaries is critical for facilitating technological knowledge transfer (Fang et al. 2010; Gaur et al. 2007; Inkpen and Beamish 1997). This may make subsidiaries more likely to better understand the breadth and depth of the headquarters’ technological knowledge base (Bjorkman et al. 2004; Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000). Fang et al. (2010, 2013) emphasize the criticality of the interplay between the headquarters’ technological knowledge resources and its subsidiary’s technological relatedness. For these reasons, the organizational inertia associated with this close headquarters–subsidiary relationship can heighten the investment irreversibility and hysteresis effect (Kim et al. 2012; Shane 1995).

For example, two Korean Electronics illustrated earlier have dispatched director-level R&D personnel to their main manufacturing subsidiaries in China, Vietnam, and India; moreover, even in the early stages of these manufacturing subsidiaries, all R&D personnel dispatched were Korean. The close connections between these manufacturing subsidiaries in China, Vietnam, and India and their headquarters make it hard for the decision-makers in Korea to ignore the existence of these subsidiaries, complicating any decision to divest them, even when suffering deteriorating macroeconomic market conditions. For these reasons, the higher the technological knowledge transfer to a subsidiary from its headquarters, the more likely organizational stickiness and the less likely a subsidiary’s divestment is to take place. Hence,

Hypothesis 3: Under hostile host market conditions, a subsidiary having more transferred technological knowledge from its headquarters is less likely to be divested than those less.

3 Research Methodology

3.1 Data and Sample

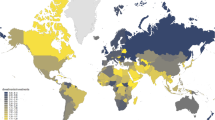

We empirically test our hypotheses utilizing 5306 observations of foreign production subsidiaries of 439 Korean multinational companies that were publicly listed on the Korea Stock Exchange (KSE) during the period 1990 through 2012. We believe that FDIs of Korean MNCs are well suited for empirically testing our primary hypotheses, since their FDIs are present in all continents of the world and exposed to diverse rates of market growth across international borders. During this period, 583 subsidiaries from our sample of observations were divested.

We refer to multiple data sources to collect information about Korean MNCs and their foreign subsidiaries. Three primary sources are (1) the Korean Ministry of Strategy and Finance (KMSF) database for investment flows between headquarters and foreign subsidiaries; (2) DataPro database for financial information on parent MNCs; (3) the Korea Listed Companies Association (KLCA) database for investment information on Korean MNCs’ foreign subsidiaries.

3.2 Dependent Variable

In order to capture how much earlier a subsidiary was divested relative to other subsidiaries during each observation year (i.e., the hazard rate of each subsidiary), we consider both the survival duration and divestment event (i.e., divested or not) using an event history analysis. We explain how the dependent variable is computed in the analytical procedure and model specification section.

3.3 Independent Variables

3.3.1 Hostile Host Market Conditions

Considering that changes in host market demand reflect favorable or hostile economic conditions for MNCs’ production and sales in their host countries, we employ two alternative indices for market demand at the host country level. We measure hostile market demand conditions as the negative value of the annual percentage change in consumer spending is multiplied by the number of years when the negative value of the annual percentage change in consumer spending persists at each host country (Fox et al. 2004; Mankiwand and Summers 1986). We refer to a commercial database of TradingEconomics.

3.3.2 Vertically-Integrated Subsidiary with Its Headquarters

To test hypothesis 2, we operationalize this variable as a ratio of a focal subsidiary’s intermediate goods sales to headquarters which it belongs (including both the parent and other peer subsidiaries) in a particular year to the total sales of the subsidiary in the same year. In some cases, we also consider the cases of which headquarters provide intermediate goods to foreign assembly factories from a home country. We locate the information on the vertical integration of Korean MNCs from the KMSF database. For example, Samsung Electronics has 28.7% of subsidiaries that are vertically integrated with its headquarters, and LG Electronics has 27.9%.

3.3.3 Top Management Team Member Dispatched from Headquarters

To test hypothesis 3, following previous studies (Benson and Pattie 2009; Forstenlechner and Mellahi 2011; Harzing 2001; Mitsuhashi et al. 2000), we measure this variable as a continuous variable, with a ratio of a member of the top management team members who is dispatched (or rotated) from MNC headquarters (or from subsidiaries) to a focal subsidiary in a particular year to the total employees of the subsidiary in the same year. We excluded an expatriate executive(s) whose terms are below one year at a focal subsidiary because we would like to reflect the characteristic of hysteresis effect. We collect the information on the dispatching of top management teams of Korean MNCs using the same sources regarding vertical integration.

3.3.4 Technological Knowledge Shared by Headquarters

To test hypothesis 4, following previous studies (Benson and Pattie 2009; Kim et al. 2012; Mitsuhashi et al. 2000; Shane 1995), we measure this variable as a continuous variable, with 1 indicating that a ratio of engineers and R&D personnel from its headquarters who are dispatched to a focal subsidiary in a particular year to the total employees of the subsidiary in the same year. We find the information on the dispatching of engineers and R&D personnel of Korean MNCs using the same sources regarding vertical integration.

3.4 Control Variables

We control for a set of factors also thought to influence subsidiary divestments. First, we include each subsidiary’s performance measured as each subsidiary’s return on assets (ROA). Since the profitability of a subsidiary can be an indicator with regard to a subsidiary divestment decision, we control for the ROA of each subsidiary. Degree of subsidiary ownership reflects the MNC’s involvement in the investment and effective control of a subsidiary operation. We measure this variable as a percentage of ownership shares for a focal subsidiary by its parent. We predict that if a degree of subsidiary ownership by its parent is higher, the subsidiary is considered to have lower divestment ratios (Hennart et al. 1998). In addition, subsidiary size is also expected to influence the survival of subsidiaries since foreign affiliates with greater resources or capabilities have additional organizational slack that helps them cope with financial difficulties (Reuer and Leiblein 2000). Specifically, larger subsidiaries (Dhanaraj and Beamish 2004) are predicted to live longer. We measure subsidiary size as the log of total assets for each subsidiary. Larger investment has the inherent risks of irreversibility and sunk cost, affecting a firm’s slow response to new changes (Dixit 1992; O’Brien and Folta 2009). Hence, we control investment as the log of total investment amount for each subsidiary.

We also take into account of host country effects by including each country’s log of GDP since this may entice firms to maintain businesses in order to capture growth opportunities or larger market merits. We use an International Monetary Fund dataset for the host country GDP. The cultural distance and geographic distance between Korea and each host country are also controlled. The cultural distance is measured using Kogut and Singh’s (1988) index, and the geographic distance is measured using the log of great circle distance between a home and host countries according to the coordinates of the geographic center of the countries (Berry et al. 2010). The source of a great circle distance between countries is from CIA Factbook (Berry et al. 2010). The political openness and social openness of each host country are measured using numerous interview feedbacks noted in the World Competitiveness Report as the same operationalization by Dhanaraj and Beamish (2009).

Factor scores for political openness that is excerpted from “national protectionism, government control on international alliances, popularity of international alliances, openness of trade policies, and openness to foreign firms’ acquisitions” and factor scores for social openness that is excerpted from “equal treatment of foreigners, openness to foreign cultures, and openness to immigration laws to foreign employment” from a factor analysis of these eight measures are exploited in this study. We did a confirmatory analysis for these two variables, and Cronbach’s alpha for political openness is 0.874, and that for social openness is 0.891. Higher scores of political openness and social openness means more politically and socially open and fewer restrictions to foreigners and foreign firms.

Cultural distance and geographic distance are expected to increase foreign subsidiaries’ management costs and positively affect their divestments, whereas political openness and social openness are expected to decrease foreign subsidiaries’ management costs and negatively affect their divestments. The hassle factor is operationalized by an 11-item measure suggested by Schotter and Beamish (2013) with the same sources that were used by them. According to Schotter and Beamish (2013, p. 525), “contextual hassles…affect individual managers’ well-being when spending time in creation locations.” In other words, “location determinants…matter to managers personally” related to “human resources, tourism…international relocation and business travel”, etc. This personal context of hassle factor may cause “managerial location shunning” that in turn it is likely to increase foreign subsidiaries’ management costs and positively affect their divestments.

Foreign exchange rate uncertainty is one of the most important environmental factors that have positive effects of external uncertainty on firm’s temporary inactivity and tardy responses to challenging transitions (Dixit 1992; O’Brien and Folta 2009). Hence, following the previous literature (Chung et al. 2015), we control for foreign exchange uncertainty which is measured by host country currency change relative to the currency of the home country, and currencies of third countries where affiliated foreign subsidiaries and customers are located.

Parent firm-level variables are also expected to influence the survival of subsidiaries since foreign affiliates with greater parental resources or capabilities have additional organizational slack to cope with financial difficulties (Reuer and Leiblein 2000). We measure parent firm size as the log of total assets for each subsidiary’s parent firm. Second, a parent firm’s prior experience of operating within foreign countries helps its subsidiaries better respond to volatile environments within other countries (Chung et al. 2010). We use a count-year of experience based on the sum of operating years for all subsidiaries at the end of each year to measure each parent firm’s international experience (Delios and Beamish 2001; Padmanahan and Cho 1999).

MNCs’ international diversifications can benefit these firms “by shifting operations in response to changes such as foreign exchange rate fluctuations or product market condition vacillations” (Chung et al. 2013, p. 124). These MNCs can have more benefits from their international diversifications when volatility increases as the value of the option increases, and hence, these firms’ investment in international diversification can cause to increase option values so does irreversibility. Therefore, if MNCs have more international diversifications, it is predicted that they are less likely to be divested their subsidiaries. International diversification is measured by the same operationalization of Chung et al. (2013), which used the same procedure of a composite measure by Lu and Beamish (2004).

When a foreign subsidiary is isolated from other subsidiaries within a given host country, then the subsidiary is more likely to be divested when faced with the host country’s hostile market uncertainty. On the other hand, a subsidiary integrated with its headquarters and/or subsidiaries is less likely to be divested and may survive longer. Following Feinberg and Gupta (2009), the intra-firm trade ratio is measured as the ratio of a specific subsidiary’s sales to other subsidiaries in the MNC to which it belongs (including both the parent and other subsidiaries) to the total sales of the subsidiary at each year. This variable ranges from 0 to 1.

The presence of parental top management team members in the subsidiary would dampen the effect of hostile environment on subsidiary performance. Yet, there may be a greater need of local top management team members at the helm if the host environment is not supportiveFootnote 1 since local top management team members who would represent an MNC’s local commitment and have a more importance of local employees would be another source of hysteresis. Given that our main focus on key own expatriates associated with headquarters-subsidiary relationship, we control for local top management team ratio in examining its impact on subsidiary exit. Local top management team is measured by a ratio of a specific subsidiary’s local top management team members in a particular year to the total employees of the subsidiary in the same year.

We also include industry dummies using the two-digit Korea standard industry code in order to take into account the potential impact of unobserved differences in capital intensity or competition associated with different industrial characteristics on subsidiary divestment. We also control for parent firm dummies to take unobserved firm-specific factors into consideration.

3.5 Analytical Procedure and Model Specification

Since we examine the probability that a subsidiary divestment will occur under the condition that all other subsidiaries are also at risk during the same time period (Hennart et al. 1998), we adopt a Cox proportional hazard rate model as a commonly used statistical method in the event history analysis (Thomas et al. 2007). A Cox proportional hazard model takes the following form:

where h i (t) is the dependent variable denoting the hazard rate for a foreign subsidiary i to be divested at time t, h 0(t) is the baseline hazard function, x i1 to x ik are the independent variables, and β 1 to β k are the coefficients to be estimated.

A Cox hazard rate model enables us to address both censored data problems (i.e. no event in the cut-off year) and aging effects by considering duration (i.e., survival time = the ending (or be divested) year − the starting (or establishment) year of study) and event (divested or not during the years of study). Compared to parametric hazard rate models that require a prior hazard distribution function, a Cox hazard model does not assume any functional form for the underlying hazard function (Cleves et al. 2004). This method is based upon a partial likelihood and produces the instant hazard rate, i.e. the probability that the divestment of a subsidiary will occur on the condition that all other cases are also at risk at the same time (Chang and Rhee 2011; Hennart et al. 1998).

In spite of its statistical convenience since it makes no assumption of any functional form for the underlying hazard function (Cleves et al. 2004), a Cox proportional hazard rate model requires two statistical checks. For this reason, we first used the STATA command “stphtest” and found that our null hypothesis that the log hazard ratio function is constant over time was not rejected. Second, for right-censored data (i.e., cases of no divestments at the end of the observation year) the duration covers the number of years between a subsidiary’s first establishment year and final survival year. With respect to the left-censoring issue (the omission of affiliates that both entered and divested before the first year of study), we used all cases surviving at least one year at the end of 1985. Since approximately 96.3% of the firms in our data were founded after 1985, we find that left-censoring was not a concern for our samples.

4 Results

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics and correlation ratios for all variables. In order to diagnose any potential multicollinearity among variables we check the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each variable; a VIF in excess of 10 is indicative of a multicollinearity problem (Menard 1995). Our results reveal that the VIFs associated with our independent variables do not exceed 1.81, and we conclude that our sample is devoid of multicollinearity.

Table 2 includes the results for all hypotheses. Model 1 includes control variables only. Model 2 additionally includes the primary independent variables. Models 3–7 incorporate each interaction term relating to a subsidiary’s vertical integration with its headquarters (Model 3), top management team dispatched from the headquarters (Model 4), and technological knowledge shared with headquarters (Model 5) respectively. Model 6 includes all variables.

We basically find that a hostile market condition reflected in declining host market demand triggers earlier divestments. This variable affects the divestiture ratio in all models positively and significantly [e.g. β = 0.28, p < 0.001 (Model 2), β = 0.29, p < 0.001 (Model 6)].

Hypothesis 1 posits that when a subsidiary is vertically integrated with its headquarters and thus takes part in production or sales activity, hysteresis effect is heightened. This may be due to a careful decision by the headquarters to disengage the subsidiary from the whole value chain, even under an unfavorable changing environment. Its interactive relationship with declining market growth is significant [β = −0.06, p < 0.05 (Model 3), β = −0.07, p < 0.05 (Model 6)]. When we interpret this interaction effect we should consider the nonlinear nature of Cox proportional hazard rate model, and we accordingly used the recent advance of a simulation-based approach in the political science and management literature to facilitate the interpretation of our interaction results (King et al. 2000; Zelner 2009).

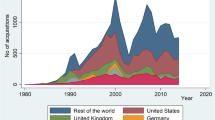

As can be seen in Fig. 1, a simulation graph illustrates the average value of these simulation estimations with vertical bars and scattered dots surrounding the two lines representing the 95% confidence intervals; as the subsidiary divestment hazard rate increases as the levels of hostile host market condition increases; however, different from the narrow intersection of the beginning of the two lines, the low level of subsidiary’s vertical integration with headquarters is curved higher up with the subsidiary hazard rate gap of approximately 1.5 than the high level of subsidiary’s vertical integration with headquarters at the highest end of hostile host market condition.

Interestingly, Fig. 1 indicates that the difference in the predicted hazard rate between low and high levels of subsidiary vertical integration with headquarters is negligible at low levels of hostile host market condition. However, at high levels of hostile host market condition the difference in the predicted hazard rate between low and high levels of subsidiary’s vertical integration with headquarters is much greater. Therefore, this simulation graph meaningfully supports Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2 tackles the negative impact of expatriate executives from headquarters on subsidiary divestments, in consideration of the strategic importance of a top management team member dispatched from headquarters (or other peer subsidiaries). This variable negatively interacts with a declining market growth rate, reducing the rate of subsidiary divestment [β = −0.15, p < 0.05 (Model 4), β = −0.18, and p < 0.05 (Model 6)]. Using the same approach in Fig. 1, the simulation-based interaction graph in Fig. 2 shows that the likelihood of subsidiary divestment hazard rate increases as the hostile host market condition levels increase when either the headquarters dispatched a top management team member ratio is high or low.

Figure 2 also reveals that the difference in the predicted likelihood of hazard rate between no dispatched top management team from headquarters and existing top management team from headquarters is extremely small, but when the hostile host market condition increases the difference between these two lines generally increases. However, interestingly, different from Fig. 2, the solid line of low top management team dispatched from headquarters shows a shape of very gentle S-curve, while the dotted line of high top management team dispatched from headquarters shows a shape of U-curve. This difference reflects the differential tendency of whether there is a high or low ratio of dispatched top management team from headquarters.

Hypothesis 3 expects a negative impact of technological knowledge shared by headquarters on subsidiary divestments because a subsidiary’s operation cannot be easily shrunk or abandoned if its headquarters transfers sufficient technological knowledge for it to become an asset to build up organizational inertia. In Model 5 (β = −0.14, p < 0.01) and Model 6 (β = −0.12, p < 0.005), the coefficients of the interaction term between declining market growth and technological knowledge transfer from headquarters are negative and significant. These results are consistent with hypothesis 4. Exploiting the same approach in Figs. 1 and 2, the simulation-based interaction graph in Fig. 3 illustrates that the likelihood of subsidiary divestment hazard rate increases, generally, as the hostile host market condition levels increase when either a subsidiary’s technological knowledge is shared with its headquarters highly or lowly. However, similar to but unlike Fig. 2, both a solid line of low technological knowledge sharing with headquarters and the dotted line of high technological knowledge sharing with headquarters show the shape of a very clear S-curve (the solid line) and that of a very faint S-curve (the dotted line). This difference reflects that there is a similar but differential tendency of whether there is high technological knowledge shared with its headquarters or there is low technological knowledge shared with its headquarters.

Some of the control variables are also worthy of discussion. The irreversibility associated with larger investment amounts or ownership share explains the lower likelihood of subsidiary divestment under hostile host market conditions. This finding also supports the argument that irreversibility is largely a function of both the amount of capital at risk and the specificity of the investments (Bragger et al. 2003; Kumar 2005; Miller and Folta 2002). The irreversibility of international investments is stronger when the size of the investments is larger or the ownership share by a parent is larger, as larger investments make it more difficult to liquidate capital assets in one country and relocate the funds to another country than do small investments (Dixit and Pindyck 1994). Firms with larger investments (or large ownership shares) in a subsidiary would have a more difficult time deciding to divest it compared to those with smaller investments, since divesting a larger subsidiary (or a subsidiary with large ownership shares by its parent) means potentially greater losses.

Cultural distance shows the predicted impact on divestments while geographic distance shows the mixed and relatively weak anticipated impact on divestments. Hence, cultural distance may significantly and practically increase foreign subsidiaries’ management costs and positively affect their divestments, while geographic distance weakly supports this phenomenon. MNC international diversification shows the expected impact on divestments, which supports our rationale of option and irreversibility. Intra-firm trade ratio shows the predicted impacts on divestments, indicating the influence of intra-firm connectedness on the factors of hysteresis. Finally, local top management team also shows the assumed impact on divestments, suggesting that an MNC’s local commitment and a strategic importance of local employees would be another source of hysteresis and, thus, may hinder divestments.

5 Discussion

In this study, we examine why foreign subsidiaries of MNCs are not divested even when they face hostile market conditions in their host countries. We take the hysteresis perspective, arguing that relationship-specific investment between foreign subsidiaries and their headquarters generates the hysteresis effect, thereby reducing the probability of subsidiary divestment even in unfriendly host country market conditions. We contribute to the hysteresis and foreign divestment literature by conceptualizing how the hysteresis effect caused by organizational and environmental factors deters the divestment of a firm’s foreign subsidiaries.

According to the profitmaking motivation of for-profit firms, MNCs divest a subsidiary undergoing economic hardship in its host country market. However, not all subsidiaries are divested when tough economic conditions in the host market make it hard for subsidiaries to survive or prosper. We find that even under hostile host country market conditions, those subsidiaries with higher importance to the headquarters are less likely to be divested. To be more specific, while our empirical results show that subsidiaries exposed to declining market growth are more likely to be divested, a subsidiary’s vertical integration with its headquarters delays its divestment even under hostile economic conditions. This result implies that a subsidiary’s divestment decision is not based solely on its host country’s economic conditions, but is entangled with its relation-specific investment from its headquarters. In other words, divestment does not take place as expected traditionally, but is rather delayed due to the hysteresis associated with a subsidiary’s importance to the headquarters.

In addition, while the nature of production is an important factor in the subsidiary divestment decision, there are other important dimensions. Among the investment that an MNC might make in its foreign subsidiaries, human capital and technological investment are among the most important. With regard to the former, our findings support the dispatching of TMT members from the headquarters as a factor that delays subsidiary divestment. Human capital investment in foreign subsidiaries reflects the strong relationship between them and their headquarters as well as their strategic importance. An MNC’s higher investment in a foreign subsidiary indicates that the subsidiary contributes to the achievement of the parent MNC’s global strategic objectives (Dossi and Patelli 2008; Gates and Egelhoff 1986).

In cases where the headquarters engage in committed and, therefore, difficult-to-reverse actions such as investing in human resources and knowledge in foreign subsidiaries, MNCs may face higher opportunity costs when divesting foreign subsidiaries because of the potentially high sunk costs of those investments (Bragger et al. 2003; Kumar 2005; Miller and Folta 2002). Assigning a TMT member to a subsidiary is not only costly, but also results in the TMT making subsidiary-specific investments during its tenure at the subsidiary. Subsidiary divestment may thus mean the knowledge accumulated on how to manage in that specific local market is wasted.

We also find that technological investment in subsidiaries makes it hard for MNCs to divest them, even under hostile economic conditions in their host countries. Kogut and Kulatilaka (2001) note that the costs of altering tightly coupled technology imply that firms persist in their old ways beyond what is advisable to maintain present net value. In other words, when a tightly knit technological relationship between headquarters and their subsidiaries exists, the cost of divestment is higher since relation-specific investment in the technological relationship makes the divestment of the subsidiary less attractive.

From these empirical results, we can draw practical implications. For example, value chain activities are critical to an MNC. If any parts of a final product are in short supply, this shortage of parts can be detrimental to the success of the whole company. For this reason, even when it makes sense to divest a subsidiary because of the host country’s market conditions, it may not be the best strategy to divest a subsidiary whose production is a critical part of the whole value chain activities of a firm, which we call the hysteresis effect.

Our results also support the concept that a subsidiary connected to the headquarters has strategic importance. Our findings imply that whether MNCs are more likely to keep a subsidiary alive may depend not on the number of other subsidiaries in the country but on how tightly they are connected to the headquarters. In today’s knowledge economy, the heightened level of competition makes it difficult for firms to forgo learning on managing in foreign markets, which should be a good reason not to divest the subsidiary. Given that aligning different value chain activities globally requires relationship-specific investment, divesting a subsidiary may mean forgoing all previous learning. In addition, as Gaur and Lu (2007) argue, should subsidiaries be divested, the arbitrage benefits gained from the investment may be wasted as well. In particular, managing in hostile environments may provide MNCs with opportunities to learn things that are rare, giving another incentive to keep the subsidiary in trouble. In addition, if a subsidiary of importance is divested for economic reasons unrelated to the competence of the TMT, it would be hard for the MNC to attract other talented TMT members to take on overseas assignments, thus hampering potential learning further. Therefore, firms tend to be reluctant to abandon their current investments and instead continue their projects.

Our research has some limitations, which provide ideas for possible future research directions. First, while we examined the drivers of the hysteresis effect by using hostile host country economic conditions as the context, future studies may investigate the performance implications of the hysteresis effect. While the finding that relation-specific investment by the headquarters in their foreign subsidiaries serves as a source of hysteresis is meaningful, the resource-based view suggests that specific investments rather make firms competitive. Future studies may thus examine if relation-specific investment by the headquarters in their subsidiaries is valuable when the economic conditions of the host markets favor divestment.

Second, it would also be informative to examine how local people in a subsidiary’s TMT affect the hysteresis effect and subsidiary divestment, since increased localization has enticed MNCs to depend more on local people when making decisions. It would also be interesting to study the impact of knowledge created by a foreign subsidiary itself. Such a knowledge-generating subsidiary can be considered to be a “center of excellence” in the age of “creative destruction”, lending it further importance from its parent MNC’s standpoint. Lastly, other countries’ foreign direct investment datasets can be compared to allow for the generalization of our primary arguments and findings. It would be particularly interesting to examine geographic differences in the hysteresis effects of the same factor(s), given that MNCs in different countries are exposed to different levels of environmental challenges and threats.

Notes

We thank an insightful comment for an anonymous reviewer who raised this issue.

References

Bauer, M. (2006). What have we acquired and what should we acquire in divestiture research? A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 32(6), 751–785.

Belderbos, R., & Zou, J. (2009). Real options and foreign affiliate divestments: A portfolio perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(4), 600–620.

Benito, R. G. (2005). Divestment and international business strategy. Journal of Economic Geography, 5(2), 235–251.

Benito, G. R. G., & Welch, L. S. (1997). Internationalization processes—new perspectives for a classical field of international management. Management International Review, 37(2), 7–25.

Benson, G. S., & Pattie, M. (2009). The comparative roles of home and host supervisors in the expatriate experience. Human Resource Management, 48(1), 49–68.

Beret, P., Mendez, A., Paraponaris, C., & Richez-Battersti, N. (2003). R&D personnel and human resource management in multinational companies: between homogenization and differentiation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(3), 449–468.

Berry, H., Guillen, M. F., & Zhou, N. (2010). An institutional approach to cross-national distance. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 1460–1480.

Bjorkman, I., Barner-Rasmussen, W., & Li, L. (2004). Managing knowledge transfer in MNCs: The impact of headquarters control mechanisms. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 443–455.

Bowman, E. H., & Hurry, D. (1993). Strategy through the option lens: An integrated view of resource investments and the incremental choice process. Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 760–782.

Bragger, J., Bragger, D., Hantula, D., Kirnan, J. P., & Kutcher, E. (2003). When success breed failure: History, hysteresis, and delayed divestiture decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 6–14.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. C. (1998). Analyzing foreign market entry strategies: Extending the internalization approach. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(3), 539–562.

Caligiuri, P. M., & Colakuglu, S. (2007). A strategic contingency approach to expatriate assignment management. Human Resource Management Journal, 17(4), 393–410.

Chang, S. J., & Rhee, J. H. (2011). Rapid FDI expansion and firm performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(8), 979–994.

Cho, K. R. (1990). The role of product-specific factors in intra-firm trade of U.S. manufacturing multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(2), 319–330.

Chow, Y. K., & Hamilton, R. T. (1993). Corporate divestment: An overview. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 8(5), 9–13.

Christophe, S. E. (1997). Hysteresis and the value of the U.S. multinational corporation. Journal of Business, 70(3), 435–462.

Chung, C. H., Lee, S. H., Beamish, P., & Isobe, T. (2010). Subsidiary expansion/contraction during times of economic crisis. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(3), 500–525.

Chung, C. C., Lee, S.-H., Beamish, P. W., Southam, C., & Nam, D. (2013). Pitting real options theory against risk diversification theory: international diversification and joint ownership control in economic crisis. Journal of World Business, 48, 122–136.

Chung, C. C., Park, H. Y., Lee, J. Y., & Kim, K. (2015). Human capital in multinational enterprises: Does strategic alignment matter? Journal of International Business Studies, 46, 806–829.

Cleves. M. A., Gould, W. W., & Gutierrez, R. G. (2004). An introduction to survival analysis using STATA. Texas: A STATA press publication.

Cuypers, I. R. P., & Martin, X. (2010). What makes and what does not make a real option? A study of international joint ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(1), 47–69.

Dai, L., Eden, L., & Beamish, P. W. (2013). Place, space, and geographical exposure: Foreign subsidiary survival in conflict zones. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(6), 554–578.

Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. (2001). Survival and profitability: The roles of experience and intangible assets in foreign subsidiary performance. Academy of Management Journal, 44(5), 1028–1038.

Dhanaraj, C., & Beamish, P. W. (2004). Effect of equity ownership on the survival of international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 25(3), 295–305.

Dhanaraj, C., & Beamish, P. W. (2009). Institutional environment and subsidiary survival. Management International Review, 49(3), 291–312.

Dhanaraj, C., Lyles, M. A., Steensma, H. K., & Tihanyi, L. (2004). Managing tacit and explicit knowledge transfer in IJVs: The role of relational embeddedness and the impact on performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 428–442.

Dixit, A. K. (1989). Entry and exit decisions under uncertainty. Journal of Political Economy, 97(3), 620–638.

Dixit, A. K. (1992). Investment and hysteresis. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 6(1), 107–132.

Dixit, A., & Pindyck, R. S. (1994). Investment under uncertainty. Princeton: Princeton U Press.

Dossi, A., & Patelli, L. (2008). The decision-influencing use of performance measurement systems in relationships between headquarters and subsidiaries. Management Accounting Research, 19(2), 126–148.

Driver, I. V. C., Yip, P., & Dakhil, N. (2010). Large company capital formation and effects of market share turbulence: Micro-data evidence from the PIMS database. Applied Economics, 28(6), 641–651.

Edström, A., & Galbraith, J. R. (1977). Transfer of managers as a co-ordination and control strategy in multinational organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(2), 248–263.

Edström, A., & Lorange, P. (1984). Matching strategy and human resource management in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 15(2), 125–137.

Erramilli, M. K., & D’Souza, D. E. (1995). Uncertainty and foreign direct investment: The role of moderators. International Marketing Review, 12(3), 47–60.

Fang, Y., Jiang, F., Makino, S., & Beamish, P. W. (2010). Multinational firm knowledge, use of expatriates, and foreign subsidiary performance. Journal of Management Studies, 47(1), 27–54.

Fang, Y., Wade, M., Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. (2013). An exploration of multinational enterprise knowledge resources and foreign subsidiary performance. Journal of World Business, 48, 30–38.

Feinberg, S. E., & Gupta, A. K. (2009). MNC subsidiaries and country risk: Internalization as a safeguard against weak external institutions. Academy of Management Journal, 52, 381–399.

Fisch, J. H., & Zschoche, M. (2011). Do firms benefit from multinationality through production shifting? Journal of International Management, 17(2), 143–149.

Fisch, J. H., & Zschoche, M. (2012). The effect of operational flexibility on decisions to withdraw from foreign production locations. International Business Review, 21(5), 806–815.

Forstenlechner, I., & Mellahi, K. (2011). Gaining legitimacy through hiring local workforce at a premium: The case of MNEs in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of World Business, 46(4), 455–461.

Fox, E. J., Montgomery, A. L., & Lodish, L. M. (2004). Consumer shopping and spending across retail formats. The Journal of Business, 77(S2), 25–60.

Gates, S. R., & Egelhoff, W. (1986). Centralization in headquarters–subsidiary relationships. Journal of International Business Studies, 17(2), 71–92.

Gaur, A. S., Delios, A., & Singh, K. (2007). Institutional environments, staffing strategies, and subsidiary performance. Journal of Management, 33(4), 611–636.

Gaur, A. S., & Lu, J. W. (2007). Ownership strategies and survival of foreign subsidiaries: Impacts of institutional distance and experience. Journal of management, 33(1), 84–110.

Gong, Y. (2003). Subsidiary staffing in multinational enterprises: Agency, resources, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 728–739.

Gregersen, H. B., & Black, J. S. (1996). Multiple commitments upon repatriation: The Japanese experience. Journal of Management, 22(2), 209–229.

Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge flows within multinational corporations. Strategic Management Journal, 21(4), 473–496.

Hamilton, L. C. (2006). Statistics with Stata. Updated for version 9. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Harzing, A. W. K. (2001). Who’s in charge? An empirical study of executive staffing practices in foreign subsidiaries. Human Resource Management, 40(2), 139–158.

Haynes, M., Thompson, S., & Wright, M. (2003). The determinants of divestment: A panel data analysis. Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organisation, 52(1), 147–166.

Helper, S., & Sako, M. (2010). Management innovation in supply chain: Appreciating Chandler in the twenty-first century. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(2), 399–429.

Hennart, J. F. (2009). Down with MNE-centric theories! Market entry and expansion as the bundling of MNE and local assets. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9), 1432–1454.

Hennart, J. F., Kim, D. J., & Zeng, M. (1998). The impact of joint venture status on the longevity of Japanese stakes in U.S. manufacturing affiliates. Organization Science, 9(3), 382–395.

Huchzermeier, A., & Cohen, M. A. (1996). Valuing operational flexibility under exchange rate risk. Operations Research, 44(1), 100–113.

Inkpen, A. C., & Beamish, P. W. (1997). Knowledge, bargaining power, and the instability of international joint ventures. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 177–202.

Jensen, R., & Szulanski, G. (2004). Stickiness and the adaptation of organizational practices in cross-border knowledge transfer. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(6), 508–523.

Kim, Y. C., Lu, J. W., & Rhee, M. (2012). Learning form age difference: Interorganizational learning and survival in Japanese foreign subsidiaries. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(8), 719–745.

King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2), 341–355.

Kobrin, S. J. (1988). Expatriate reduction and strategic control in American multinational corporations. Human Resource Management, 27(1), 63–75.

Kogut, B., & Kulatilaka, N. (1994). Operating flexibility, global manufacturing, and the option value of a multinational network. Management Science, 40(1), 123–139.

Kogut, B., & Kulatilaka, N. (2001). Capabilities as real options. Organization Science, 12(6), 744–758.

Kogut, B., & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(3), 411–432.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1993). Knowledge of the firm and the evolutionary theory of the multinational corporation. Journal of International Business Studies, 24(4), 625–645.

Kotabe, M., & Murray, J. Y. (1990). Linking product and process innovations and modes of international sourcing in global competition: A case of foreign multinational firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(3), 383–408.

Kumar, M. V. S. (2005). The value from acquiring and divesting a joint venture: A real options approach. Strategic Management Journal, 26(4), 321–331.

Lee, D., & Madhavan, R. (2010). Divestiture and firm performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 36(6), 1345–1371.

Lee, S. H., & Song, S. (2012). Host country uncertainty, intra-MNC production shifts, and subsidiary performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11), 1331–1340.

Lu, J. W., & Beamish, P. W. (2004). International diversification and firm performance: The S-curve hypothesis. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 598–609.

Luo, Y. (2002). Stimulating exchange in international joint ventures: An attachment-based view. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(1), 169–181.

Madura, J., & Murdock, M. (2012). How and why corporate divestitures affect risk. Applied Financial Economics, 22(22), 1919–1929.

Madura, J., & Whyte, A. M. (1990). Diversification benefits of direct foreign investment. Management International Review, 30(1), 73–85.

Mankiwand, N. G., & Summers, L. H. (1986). Money demand and the effects of fiscal policies. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 18(4), 415–429.

Martin, S. (1996). Protection, promotion and cooperation in the European semiconductor industry. Review of Industrial Organization, 11(5), 721–735.

Masten, S. E., Meehan, J. W., & Snyder, E. A. (1991). The costs of organization. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 7(1), 1–25.

Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (2000). Closure and divestiture by foreign entrants: The impact and entry and post-entry strategies. Strategic Management Journal, 21(5), 549–562.

Menard, S. (1995). Applied logistic regression analysis: Sage University series on quantitative applications in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing.

Miller, K. D., & Folta, T. B. (2002). Option value and entry timing. Strategic Management Journal, 23(7), 655–665.

Mitsuhashi, H., Park, H. J., Wright, P. M., & Chua, R. S. (2000). Line and HR executives’ perceptions of HR effectiveness in firms in the People’s Republic of China. International Journal of Human Resources Management, 11(2), 197–216.

Nhoria, N., & Ghoshal, S. (1994). Differentiated fit and shared values: Alternatives for managing headquarters-subsidiary relations. Strategic Management Journal, 15(6), 491–502.

O’Brien, J. P., & Folta, T. B. (2009). Sunk costs, uncertainty and market exit: A real options perspective. Industrial and Corporate Change, 18(5), 807–833.

Oliva, T. A., Day, D. L., & MacMillan, I. C. (1988). A generic model of competitive dynamics. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 374–389.

Padmanahan, P., & Cho, K. R. (1999). Decision specific experience in foreign ownership and establishment strategies: Evidence from Japanese firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(1), 25–43.

Reuer, J. J., & Leiblein, M. J. (2000). Downside risk implications of multi-nationality and international joint ventures. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 203–214.

Schotter, A., & Beamish, P. W. (2013). The hassle factor: An explanation for managerial location shunning. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(5), 521–544.

Shane, S. (1995). Uncertainty avoidance and the preference for innovation championing roles. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(1), 47–68.

Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 27–43.

Tarique, I., Schuler, R., & Gong, Y. (2006). A model of multinational enterprise subsidiary staffing composition. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(2), 207–224.

Thomas, D., Eden, L., Hitt, M., & Miller, S. (2007). Experience of emerging market firms: The role of cognitive bias in developed market entry and survival. Management International Review, 47(6), 845–867.

Tsai, W., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital and value creation: The role of intra-firm networks. Academy of Management Journal, 41(5), 464–476.

Turnbull, P., Oliver, N., & Wilkinson, B. (1992). Buyer-supplier relations in the UK—automotive industry: Strategic implications of the Japanese manufacturing model. Strategic Management Journal, 13(2), 159–168.

Yan, A., & Zeng, M. (1999). International joint venture instability: A critique of previous research, a reconceptualization, and directions for future research. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(2), 397–414.

Zelner, B. A. (2009). Using simulation to interpret results from logit, probit, and other nonlinear models. Strategic Management Journal, 30(12), 1335–1348.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2015S1A3A2046811).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Song, S., Lee, J.Y. Relationship with Headquarters and Divestments of Foreign Subsidiaries: The Hysteresis Perspective. Manag Int Rev 57, 545–570 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-017-0317-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-017-0317-z