Abstract

More and more firms are entering foreign markets. However, while research on international entry and expansion has been a particularly important topic in the literature, there has been a dearth of empirical research explaining firms’ exit decisions from foreign markets. To address this gap in the literature, this study examines the exit behavior of emerging market MNCs. More specifically, we explore the firms’ exit behavior in the context of the headquarters-foreign affiliate relationship. To this end, this study develops a model whereby the impact of performance on the firms’ exit decision is moderated by innovation capability and international experience. Using secondary and primary data collected from multiple respondents from Chinese outward foreign direct investment firms, the findings indicate that innovation capability moderates the relationship between performance and exit decision. However, and contrary to expectations, the study suggests that incremental and radical innovation have an opposite contingent effect on the performance-exit relationship. In addition, the moderating effect of innovation capability on the performance-exit relationship was further moderated by international experience. Implications of these findings along with the limitations of the study are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The trend toward globalization has stimulated many firms to enter foreign markets. However, the decision by a firm to enter a foreign market is not irreversible. Not surprisingly, news media regularly report on firms which have been forced to exit foreign markets. Target’s withdrawal from the Canadian market, and Avon Products’ exit from the Irish and South Korean market, provide good examples of firms which have recently faced such a decision (Wahba 2015).

While studies on exit strategies were first presented in the 1970s by scholars such as Boddewyn (1979), since then research focused on exit strategies has tapered off in scholarly journals (Kotabe and Ketkar 2009). Consequently, and despite the importance of the topic, we know relatively little about the factors leading firms to exit their foreign markets (Berry 2013; Soule et al. 2014). This gap in the literature is important because it has been argued that firms learn more from past failures than from past successes (Madsen and Desai 2010). Failure suggests that the firm’s existing strategy is inadequate and challenges the status quo, thereby encouraging the manager to engage in deep or mindful reflection and search for solutions to correct problems (Morris and Moore 2000; Sitkin 1992; Tsinopoulos et al. 2019).

To address this gap in the literature, this study examines the exit behavior of multinational corporations (MNCs). Exit refers to a foreign direct investment (FDI) firm’s decision to liquidate or sell an active operation in a foreign market. While poor performance is expected to play a crucial role in the firm’s exit decision, other perspectives are also worth considering (Kolev 2016; Song 2014a). This study builds on the resource-based view (RBV) and its recent dynamic capabilities theory, and focuses on the moderating impact of innovation capability and international experience to account for the firm’s exit decision.

Although poor performance may drive firms to exit a foreign market, recent studies have shown that innovation plays a crucial role in the survival and exit of firms (Cefis and Marsili 2011; Deng et al. 2014; Velu 2015) and is considered a critical element for firms that aim to achieve sustained competitive advantage (Porter 1990). This is particularly the case for firms competing in foreign markets whereby the trend towards globalization and intense global competition emphasizes the need for the firms to develop and deliver a continuous stream of innovations. Innovations are, therefore, critical for firms wishing to grow and survive in foreign markets (Hortinha et al. 2011; Tellis et al. 2009). Thus, while poor performance is expected to drive firms to exit foreign markets, innovation capabilities are expected to have an opposite effect on the firms’ exit decision. Examining how innovation capabilities may interact with performance, by strengthening or weakening the effect of performance on the exit decision is, therefore, particularly interesting. Moreover, the need to consider the moderating impact of innovation capability has been recently emphasized in studies (e.g., Menguc et al. 2014), and echoes arguments by the RBV and dynamic capabilities theory that how well the firm deploys its resources is dependent on the firms’ capabilities. In addition, by adopting the idea of ‘resource orchestration’ (see Sirmon et al. 2011), this study examines how the moderating effect of innovation capabilities can be further influenced by its international experience.

To this end, the paper addresses the following research questions: (1) what is the moderating impact of innovation capability on the performance-exit relationship? And (2) how does international experience further influence the moderating impact of innovation capability?

Addressing these research questions offers a number of contributions. Firstly, our study empirically investigates the determinants of the firm’s exit decision. Considering its recognized importance, it is crucial that more attention is paid to provide a more in-depth understanding on this issue. The focus of innovation capability is particularly interesting because it allows us to assess the opposing roles played by poor performance (that should favor the decision to exit) and innovation capability (which should favor the decision to remain) in determining whether to exit or remain in a foreign market.

Secondly, we contribute to the RBV theory by considering the moderating role of innovation capability. A long-standing criticism that has been raised in the RBV literature is that the level of resources is not sufficient to explain different outcomes (Menguc et al. 2014). Indeed, researchers have questioned whether it is the level of resources or the deployment of such resources that leads to different outcomes (Kraaijenbrink et al. 2010; Newbert 2007). Capabilities refer to a firm’s capacity to deploy resources effectively so that inputs can be transformed into desirable outcomes (Barney 1991). The degree to which these resources are deployed to develop effective strategies and make optimal strategic decisions depends on the firms’ capabilities (see Ndofor et al. 2015). To this end, the inclusion of innovation capability as a moderator allows us to examine the firm’s capacity to deploy resources to achieve the desirable outcomes. Moreover, we also distinguish between incremental and radical innovations to provide a better understanding of the complexities surrounding their effects on the relationship between performance and exit decision. By treating both constructs distinctively, we also address Slater et al. (2014) suggestion that in order to advance knowledge in this area future studies are encouraged to differentiate between incremental and radical innovation. In exploring these constructs separately, the present research shows how incremental and radical innovation capabilities have an opposite effect on the performance-exit relationship, thereby revealing a novel and interesting finding.

Thirdly, this study not only empirically examines previously untested theoretical propositions, but also adds to previous studies by adopting the idea of ‘resource orchestration’ and exploring how the moderating effect of innovation capabilities can be further influenced by its international experience. Recent developments of both the RBV and dynamics capabilities theory embrace the idea of resource orchestration, suggesting that capabilities need to be further leveraged, and that there is a need to examine the contingencies related to the firms’ strategy implementation (Sirmon et al. 2011). We extend both the RBV and dynamics capabilities arguments by theorizing that the ability of firms to leverage their capabilities is further dependent on the firm’s international experience. As international experience enables managers to have a better understanding of the foreign market (Casillas et al. 2012), it should influence the firm’s ability to leverage its innovation capability in the foreign market.

2 Theory and Research Hypotheses

2.1 Research on Foreign Exit Decision

It has been four decades since the initial research on foreign exit in the 1970s, with the pioneering contributions from Boddewyn and his colleagues (e.g., Boddewyn 1985; Boddewyn and Torneden 1973). Empirical research on the antecedents of exit decision and foreign divestment, however, is still in the early stages of research (Berry 2013). Unlike research on entry and expansion, progress in research on exit has been relatively slow due to the greater difficulty in persuading managers to share data (Benito and Welch 1997; McDermott 2010; Paul and Benito 2018). Based on different perspectives, extant studies have identified various antecedents of foreign exit decision. At the firm level, prior studies mainly focused on factors related to: (1) RBV-based theory; (2) organization learning-based theory; (3) strategy-based theory; and (4) relationship/network-based theory.

In the first research stream, RBV scholars argue that the more resources and capabilities the subsidiaries and their parent firms have, the more likely the subsidiaries will survive in the foreign markets, because these resources and capabilities are the foundation of competitive advantages and superior performance (Barney 1991). Accordingly, empirical research based on RBV has examined and found subsidiaries’ and/or the parent firms’ performance (Berry 2013; Dai et al. 2013; Song 2015), size (Belderbos and Zou 2009), advantages in intangible assets such as marketing, R&D, and technological resources (Lee et al. 2012) and capabilities (Franco et al. 2009; Giovannetti et al. 2011) have significant impact on the subsidiaries’ likelihood of foreign exit.

The second research stream paid special attention to organizational learning theory and argued that the success of foreign subsidiaries relies on the accumulation and utilization of relevant experience (Kang et al. 2017; Paul and Benito 2018), because it helps to overcome the liabilities of foreignness and avoid the pitfalls in foreign operations (Kim et al. 2010). Accordingly, empirical studies based on organizational learning theory generally found foreign exit was negatively associated with subsidiaries’ and/or the parent firms’ age (Delios and Beamish 2004), international experience (Mata and Portugal 2002), and failure experience in the same country (Yang et al. 2015).

The third research stream showed interest in the influence of strategic aspects. Strategy management scholars believe that specific strategic choices are critical to the success of foreign operations, because different strategies indicate different motivations (Mata and Portugal 2000) and costs in initial investment and subsequent management in the foreign market (Li 1995), which in turn determine the likelihood of subsidiary’s subsequent foreign exit. Accordingly, empirical studies found that the likelihood of foreign exit is significantly associated with strategies such as a subsidiary’s foreign ownership (Kim et al. 2012), entry mode strategy (Li 1995), entry destination (Koch et al. 2016), business relatedness (Tan and Sousa 2018), the parent firm’s degree of diversification and internationalization (Chung et al. 2013), and the strategic fit between the subsidiary and the parent firm (Sousa and Tan 2015).

The fourth research stream explained the foreign exit determinants from the relationship-based perspective and argued that a strong connection with its parent firm decreases the chance of a subsidiary’s being withdrawn from the foreign market, because such close relationship makes not only increases the parent firm’s commitment to the subsidiary’s business (Berry 2013) but also makes the divestment of the foreign subsidiary harmful to the related parent firm’s interest (Song and Lee 2017). Accordingly, empirical studies found that foreign subsidiaries are less likely to exit when they are vertically integrated with the parent firm (Song and Lee 2017) or when their business is highly related with that of the parent firm (Pehrsson 2010).

At the market/industry and country level, extant research on foreign exit have mainly focused on three research streams: (1) evolution-based perspective; (2) real options-based perspective; and (3) institutional theory. Studies using the evolution-based perspective have argued that the survival chance of the foreign subsidiary largely depends on the competition and population density (Hannan and Freeman 1993) due to the rule of survival of the fittest. The more intensive the foreign market competition is, the more likely a foreign subsidiary will exit. Accordingly, empirical studies found that seller concentration and industrial foreign penetration are positively associated with foreign exit (Mudambi and Zahra 2007; Sui and Baum 2014).

The second research stream using real options-based perspective paid much attention to the role of environmental uncertainty and sunk cost (O’Brien and Folta 2009). The basic argument is that when environment is uncertain, it is wise not to make a foreign exit decision because the initial entry cost (sunk cost) will reoccur if the company wants to re-enter the foreign market later (Dixit 1989). Accordingly, empirical studies found environmental uncertainty (Tan and Sousa 2018), technological turbulence, country risk (Efrat and Shoham 2012), and sunk cost (Dai et al. 2017) to have a significant association with foreign exit.

The last research stream focused on the critical role of institutions in foreign exit decision. The institutional theory has gained increasing attention as many firms have entered emerging markets as well as the surge of MNCs from emerging economies entering foreign markets. The basic argument is that institutions are quite different (particularly in the case of emerging versus developed economies) and that all kinds of institutional distance such as economic distance, cultural distance, demographic distance, and political distance increases the liability of foreignness (Barkema and Vermeulen 1997; Sousa and Bradley 2006; Xu and Shenkar 2002). Therefore, the larger the institutional distance is, the more likely a subsidiary will exit from the foreign market (Barkema et al. 1996; Kang et al. 2017).

Overall, exit studies have identified a variety of factors can influence the firm’s exit decision. However, it is important to note that extant literature tends to highlight the importance of poor performance on firm’s divestment decisions (Berry 2013). Poor performance has been generally illustrated as the most important and the strongest trigger of foreign divestment (Berry 2013; Markides and Berg 1992; Torneden 1975).

2.2 International Experience and Innovation Capability

International experience has been identified in the literature as an important determinant of the firm’s foreign operations (Dow and Larimo 2009; Oehme and Bort 2015; Tan and Sousa 2013). Given its importance, it is not surprising that studies have examined its impact across a number of different topics, including the firm’s exit decision. Specifically, some studies have suggested international experience to be an important contributor to the survival of a subsidiary (Pattnaik and Lee 2014; Shaver et al. 1997). However, whereas these studies suggest that international experience has direct impact on foreign exit decision, they differ in the expected direction of influence on international experience on foreign exit. Some argue that firms with experience in the host country are more likely to survive (Li 1995; Shaver et al. 1997), because they have more information and knowledge about the local environment than first-time foreign entrants to overcome the liability of foreignness (Kang et al. 2017; Shaver et al. 1997), and can build upon the existing network of foreign value-added activities to reduce operational uncertainties (Kogut 1983). Others believe experience may not always be helpful because firms may draw incorrect inferences from experience and misapply it to dissimilar contexts (Levinthal and March 1993; Zeng et al. 2013). Therefore, experience could have a beneficial, detrimental, or neutral effect on FDI survival (Zeng et al. 2013). This is consistent with the findings of empirical studies where international experience has negative (Chung et al. 2013; Song 2014b), positive (Kim et al. 2010; Nadolska and Barkema 2007), and no direct impact (Hennart et al. 1998; Song 2015; Yang et al. 2015) on the subsidiary exit. Due to the inconclusive effects, some studies propose that international experience should be considered as a moderator in the foreign exit decision (Gaur and Lu 2007; Kang et al. 2017; Pattnaik and Lee 2014).

The increasing importance of innovation has been acknowledged in the international business literature. Studies on innovation have recognized the vital role of innovation capability in a firm’s exit/survival (Cefis and Marsili 2005; Santos et al. 2014). The key reason is that innovation capability, defined as the ability to generate, accept, and implement new ideas, processes, products and services (Calantone et al. 2002), helps a firm to both maintain competitive advantage for short-term survival and build its competitive advantage for long-run survival (Hughes et al. 2010). Although extant studies have identified different types/dimensions of innovation, distinguishing between incremental and radical innovation based on innovation magnitude merits further attention due to its underdeveloped research state (Slater et al. 2014). Incremental (also termed as ‘exploitative’ or ‘continuous’) innovation capability refers to the ability to generate innovations that refine and reinforce existing products and services. Radical (also termed as termed as ‘explorative’, ‘discontinuous’, ‘revolutionary’, ‘pioneering’, ‘disruptive’, or ‘breakthrough’) innovation capability refers to the ability to generate innovations that substantially transform existing products and services (O’Reilly and Tushman 2004; Subramaniam and Youndt 2005).

2.3 Theoretical Foundation

The resource-based view (RBV) posits that a firm’s current level of resources constrain its strategic choice (Collis 1991). It also holds that a firm’s performance indicates the amount of excess resources (Barney 1991). As such, good performance allows a firm to experiment with new strategies, whereas poor performance greatly limits the firm’s strategic choice (Hambrick and Snow 1977). In many cases poor performance means a firm cannot provide adequate resources for it to remain in business (Fredrickson and Mitchell 1984). As such, a foreign affiliate’s (FA) performance which falls below a certain level of satisfaction may lead to the MNC’s strategic decision to exit the FA from the foreign market. Moreover, poor performance also implies that the FA’s previous strategy choice has failed to achieve the aspiration level in the host foreign market. Poor performance also suggests that future performance will stay poor or become even poorer if no changes are made (Duhaime and Grant 1984). Therefore, poor performance is likely to trigger strategic changes (Day and Wensley 1988). In this case, it is very likely that many managers make an exit decision. In contrast, strong firm performance leads to satisfaction with the current status quo and suggests that there is no need to engage in divestment decisions (Kolev 2016). Overall, this leads us to our baseline hypothesis:

Baseline hypothesis: An FA’s international performance has a negative impact on the FA’s exit decision from the foreign market.

While RBV is used to develop our baseline hypothesis, one key criticism of the RBV is that possession of resources is not sufficient to explain firm heterogeneity in strategies (Kraaijenbrink et al. 2010). Organizational capabilities, such as innovation capability which help to reconfigure and integrate resources, has become a more important determinant (Teece 2007). The reason is that, the possession of more or less resources only determines the breadth of a firm’s resource base for strategies, but whether and/or how well the firm’s existing resources can be utilized to develop effective strategies and make an optimal strategic decision, depends on the firm’s capabilities (see Ndofor et al. 2015). In this study, yielding poor performance indicates that the FA has a narrow resource base to support its strategic choice of remaining in the foreign market, thereby increasing the likelihood of a foreign exit decision. However, high innovation capabilities enable the FA to effectively use the narrow resource base to formulate better innovative strategy for business recovery, which could decrease the likelihood of exiting from the foreign market. By following this line of investigation, this present study will provide empirical evidence on whether each type of innovation capability is an effective moderator of resources in the strategic management area (e.g., Menguc et al. 2014).

Although, capabilities may enable firms to utilize existing resources in potentially effective ways, they do not guarantee organizational success (Zahra et al. 2006). And despite the close association between capabilities and the development of good strategies, how to make these good strategies work in practice involves the firms’ strategy implementation (Karna et al. 2016). The RBV, however, has been criticized for not dealing with strategy implementation issues (Barney 2001; Newbert 2007; Priem and Butler 2001). To echo this criticism, the recent development of both the RBV and dynamic capabilities theory has embraced the idea of ‘resource orchestration', suggesting that the extent of possessed resources’ value that can be realized, depends on the degree to which those resources are effectively managed (Sirmon et al. 2011). Hence, the examination of contingences related to firms’ strategy implementation and managers’ strategic choices, has been identified as an important research agenda for the RBV (see Crook et al. 2008; Sirmon et al. 2011).

Therefore, to advance research in the area it is critical to examine possible contingency effects influencing MNCs’ strategy implementation and strategic choice. Given the aforementioned moderating effect of innovation capabilities on the performance-exit link, we further theorize that the ability of firms to leverage their capabilities is further dependent on the firm’s international experience.

Resource orchestration theory argues that the possession of resources is not enough, instead firms must leverage their resources to achieve their aims (Sirmon et al. 2011). It is concerned “with the actions leaders take to facilitate efforts to effectively manage the firm’s resources” (Hitt et al. 2011, p. 64). Therefore, the conceptual framework of resource orchestration suggests that firms are dependent on their ability to effectively and efficiently leverage their resources (Wales et al. 2013). We posit that international experience is crucial in allowing the firms to more effectively and efficiently orchestrate their resources. Specifically, international experience increases the management’s ability to integrate an FA’s innovation capabilities into the existing resources bundle to improve strategic decisions (see Klepper and Simons 2000; Rothaermel and Deeds 2006; Wiklund and Shepherd 2009). Hence, in this study, international experience interacts with the FA’s innovation capabilities, such that the moderating effect of these capabilities on the performance-exit relationship is further moderated by the FA’s international experience.

To sum up, our study proposes that a foreign affiliate’s performance affects the firm’s exit decision. However, we further assert that this impact is contingent on the firm’s innovation capability and international experience. Consequently, we propose the following research framework, as shown in Fig. 1.

2.4 The Moderating Role of Innovation Capability

Our baseline hypothesis indicates that an FA’s poor performance is likely to trigger its exit from the foreign market. However, the negative relationship between the two may become different if we take the level of the FA’s innovation capability into consideration.

Incremental innovation capability refers to the ability to generate innovations that refine and reinforce existing products and services. If an FA has a high level of incremental innovation capability, MNC managers should perceive the FA to be capable of delivering innovative products that improve existing customers’ experience (Menguc et al. 2014) and thus, compete favorably among the current market players (Slater et al. 2014). In this case, if the FA yields poor performance in the foreign market, the FA with the above-mentioned capability is perceived to be in a better position to win back its customers and regain its competitive advantage through incremental innovation. Therefore, MNC managers are more likely to believe that the FA will turn the situation around in the near future and less likely to make an exit decision.

In addition, as incremental innovation capability is, to some extent, embedded in the existing market, MNC managers tend to perceive that the FA with a high level of incremental innovation capability is mostly likely to regain its competitive advantage in the current foreign market (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013), instead of in other new foreign markets. Namely, it is in the current foreign market that an FA’s incremental innovation capability has the best chance to be transformed into competitive advantage, thereby enabling MNC managers to foresee a quick turnaround. In this case, MNC managers are less likely to exit a poorly-performing FA with high incremental innovation capability. Moreover, compared with low incremental innovation capability, high incremental innovation capability enables a poorly-performing FA to formulate and implement innovation strategies more effectively. Hence, MNC managers should perceive the chance of the FA’s success in the current market to be higher if the FA has high incremental innovation capability, and are therefore, less likely to make an exit decision. In contrast, yielding poor performance, FAs with low incremental capability are perceived by MNC managers to be less able to attract customers back to them or compete favorably with existing competitors in the current market, by generating effective innovations to improve existing products and services (Baker and Sinkula 2007). This means that with low incremental capability, the FAs will be perceived to be less able to deal with the challenges of operating in the foreign market, and this perception will be more likely to lead to an exit decision. Therefore, we propose,

Hypothesis 1: The negative relationship between an FA’s international performance and the FA’s exit from the foreign market is weakened by the FA’s incremental innovation capability.

Radical innovation capability refers to the ability to generate innovations that substantially transform existing products and services. Unlike incremental innovation capability, which is short-term oriented and focuses on maintaining competitive advantage in the existing market, radical innovation capability is long-term oriented and focuses on building competitive advantage for the future (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013). If an FA has a high level of radical innovation capability, MNC managers should perceive the FA to have the ability to deliver substantially innovative products that satisfy potential customers in new market segments (Andriopoulos and Lewis 2010) and/or compete favorably among potential rivals in new segments of the current foreign market (Menguc et al. 2014; Slater et al. 2014). In this case, if an FA yields poor performance in the foreign market, the FA with high radical innovation capability is in a better position to attract new/potential customers in the existing foreign market. This releases a signal to MNC managers that, with time, the FA will be able to successfully gain more customers and regain the competitive advantage in the current foreign market. Therefore, MNC managers are less likely to exit the poorly-performing FA from the current foreign market.

Moreover, radical innovation usually involves high return (see Velu 2015), and MNC managers tend to expect that, with a high level of radical innovation capability, a poorly-performing FA should be able to obtain higher profit margin from consumers than other competitors in the current foreign market, through the development of significantly new product. In this case, MNC managers should perceive a higher chance of turning around the FA’s business and, therefore, are more likely to keep the poorly-performing FA in the foreign market. In contrast, if the poorly-performing FAs have low radical innovation capability, they are more likely to leave the foreign market. The reason is that their current products/services are already in a disadvantageous position in the current market and MNC managers tend not to believe that FAs with low radical innovation capability will be capable of developing and delivering substantially innovative products to transform current products/services to satisfy potential customers. Therefore, we expect that,

Hypothesis 2: The negative relationship between an FA’s international performance and the FA’s exit from the foreign market is weakened by the FA’s radical innovation capability.

2.5 The Moderating Role of International Experience and Innovation Capabilities

International experience refers to the amount of knowledge and skills an MNC has accumulated when operating in a foreign market (see Dow and Larimo 2009). Such experience enables MNCs to have a better understanding of foreign markets and the way in which foreign businesses work (Lu et al. 2014), thereby better identifying customers, marketing strategies, opportunities for growth (Meyer and Gelbuda 2006; Sousa et al. 2008). Additionally, prior international experience helps MNCs to develop organizational capabilities in overcoming the difficulties of implementing strategies in foreign markets (Nielsen and Nielsen 2011). Therefore, if appropriately applied, international experience increases the probability of MNCs’ survival in foreign market operations (Barkema et al. 1996; Gaur and Lu 2007; Song and Lee 2017; Sousa et al. 2008).

A high level of incremental innovation capability indicates a high ability to generate innovative strategies that makes it more likely for a poorly-performing business to stay in the market by refining and reinforcing existing products/services. However, it is likely that FAs with high levels of incremental innovation capabilities may not be sufficiently knowledgeable about their capabilities in identifying the best innovative strategy among alternatives and effectively implementing it. In this case, international experience, which shapes the FAs’ ability to select the most effective innovative strategy (see Cavusgil and Zou 1994; Sousa et al. 2008), and effectively implement it (see Gaur and Lu 2007), should complement and reinforce the effect of the FAs’ incremental and radical innovation capability in creating the perception of that FA’s ability to turn poor performance and remain in the foreign market.

Specifically, international experience enables an FA to identify potential advantages and pitfalls associated with different innovative strategies aimed at making a poorly-performing business successful (see Dow and Larimo 2009), based on which MNCs are able to more accurately estimate the probability of business recovery among alternative strategic solutions. In addition, international experience allows MNCs to have a better understanding of the foreign market mechanism (Lu et al. 2014) and therefore, MNCs are able to make the best out of their innovation capabilities to develop an optimal scheme to turn the business around. Moreover, international experience helps managers to deal with the challenges in the foreign market (Sousa et al. 2008) and, therefore, MNC managers are more optimistic/confident when making strategic decisions about the recovery of a poorly-performing business (see Nielsen and Nielsen 2011).

Finally, international experience enables an FA to implement innovative strategies more effectively to improve poor performance across borders (see Gaur and Lu 2007), thereby increasing the perception of future business recovery. Due to the above reasons, when an FA yields low international performance, FAs with high international experience should be perceived to be more able to take advantage of their innovation capabilities and turn the business around. In this case, FAs are less likely to exit from a foreign market. In contrast, FAs with a low level of international experience will perceived to be less able to make accurate estimation about the recovery probabilities of alternative innovation strategies, formulate optimal innovative strategy for recovery, and implement the innovative strategies in effective/efficient ways (see Hultman et al. 2011). Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3: High international experience strengthens the moderating effect of incremental innovation capability on the FA’s international performance-exit relationship, such that this negative relationship is strongest when both incremental innovation capability and international experience are low.

Hypothesis 4: High international experience strengthens the moderating effect of radical innovation capability on the FA’s international performance-exit relationship, such that this negative relationship is strongest when both radical innovation capability and international experience are low.

3 Methodology

3.1 Sample and Data Collection Procedure

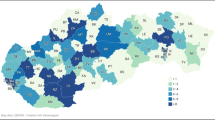

The data were collected from Chinese outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) firms. According to the OECD (2008) definition, a Chinese OFDI firm in our study refers to a firm which has registered in mainland China and has invested in another economy. The selection of China as our research setting is particularly interesting as China is currently a major investor and is expected to become the world’s number one international investor by 2020 (Anderlini 2015). In addition, Chinese companies abroad are reported to have one of the world’s highest failure rates (Hill 2012). We obtained the full list of 15,541 Chinese OFDI firms from the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, and used firms from the top 12 provinces/municipal cities on the basis of OFDI flows (Zhejiang, Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong, Fujian, Shanghai, Liaoning, Tianjin, Hunan, Heilongjiang, Henan, and Beijing) as our sampling frame. Due to the different number of MNCs in each province, a geographic area ‘province’-based stratified random sampling method was adopted to reach a representative final sample of 1000 OFDI firms.

Data were collected through a questionnaire survey, which was developed in English and translated into Chinese by a bilingual academic. Pilot tests were undertaken with nine managers to check the face validity as well as readability of the questionnaire. To ensure equivalence of the translated Chinese items, translation and back-translation of the questionnaire were independently performed by four bilingual researchers and then subsequently compared by the authors. The analysis of FDIs in the sample is made for the period 1980–2012. To get the data about foreign exit/non-exit decision, managers were asked to identify whether the OFDI firms have ever had foreign exit decisions. An answer “no” indicates the firms did not have any foreign exit. If the answer is “yes”, indicating the firms had foreign exit decisions, managers were further asked to select the most recently divestment decision so that they could easily recall the information requested (see Fowler 1995).

To prevent potential common method bias, we followed the Chang et al. (2010) suggestion and collected data from multiple respondents (one manager is responsible for the HQ’s business, and the other for the FA’s business). In addition, both primary and secondary sources were used. Specifically, the independent variables were evaluated by the respondents and the dependent variable (i.e., Exit from a foreign market) was from the official published archive. As such, common method bias should not be an issue for this study.

Of the 1000 sampled OFDI firms, 360 questionnaires from 180 firms were complete and valid, yielding an effective response rate of 18%. To test non-response bias, a t test was conducted to compare early and late responses (Armstrong and Overton 1977). No statistically significant differences were found, indicating that non-response bias was not an issue in the study. More information about the grouped sample (i.e., exit firms vs non-exit firms) is presented in Table 1.

Regarding the total 180 sampled OFDI firms, the Chinese parent companies have an average of 7260 full-time employees, with 22 years’, 11 years’, and 8 years’ operation in home market, international business, and the specific host market, respectively. More than 60% of the Chinese parent companies have annual sales volumes of one billion Chinese Yuan and above. The parent firms were broadly spread across 18 industries. High-tech manufacturing firms and low-tech manufacturing firms account for 18% and 27% of the whole sample, respectively. Overall, services account for 55% of the whole sample. In terms of destinations, Asia (58%), America (27%), and Europe (9%) are the most popular regions. The majority (83%) of the host countries are developed countries. Regarding their ownership, more than 80% of the parent companies are privately-owned. In terms of the FA establishment method, greenfield investments account for 78% of the sample firms.

3.2 Measurement

3.2.1 Dependent Variable

The dependent variable exit is a binary variable representing the decision of an FA to exit from a foreign market. Exit takes a value of 1 if the FA made an exit decision, otherwise it equals 0. In our dataset, 102 MNCs take a value of 0 and 78 MNCs take a value of 1.

3.2.2 Independent Variables

Following the suggestion that researchers should use multidimensional measures for capturing innovation capability, in this study Incremental Innovation Capability was measured via a three-item scale and Radical Innovation Capability was also measured by three items based on the work by Subramaniam and Youndt (2005). The firm’s International Experience was measured as the number of years of the first foreign subsidiary. A firm’s decision on whether to exit is a function of performance relative to a firm-specific threshold rather than economic performance (Gimeno et al. 1997), and the measure of performance should be based on the comparison with that threshold. As such, International Performance was measured as the overall satisfaction with an FA’s international performance in the past three years using a five-item scale adapted from Lages et al. (2008).

3.2.3 Control Variables

The following variables that could threaten the accuracy of our model estimation are controlled in our study: HQ size, FA size, HQ age, FA age, PLC stage, product type, FA establishment method, HQ ownership, industry type, economic stage, political freedom, institutional distance, embeddedness, FA strength, and organizational slack. The Appendix provides an overview of the operationalization of the constructs.

4 Analysis and Results

4.1 Reliability and Validity

AMOS 20 was used to test the basic assumptions of multivariate analysis, including normality, homoscedasticity, linearity, independent errors, and multi-collinearity (Hair et al. 2010). To avoid collinearity between interaction terms, mean-centered z-standardizing values were used (Dawson 2014). For the two-way interactions, we first calculated the centered value of international performance and the two types of innovation capabilities. Then the centered value of international performance was multiplied by that of incremental innovation capability and radical innovation capability, respectively. The four three-way interaction terms were calculated using the same approach (see also Brouthers et al. 2015). The results suggest that all the assumptions are well met. We used AMOS 20 to conduct CFA. As shown in the Appendix, the CFA model indicates a close fit to the data (CFI = 0.92; TLI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.07). All scale reliabilities meet the threshold of 0.70, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values range from 0.64 to 0.76, well above the threshold of 0.50 (Bagozzi and Yi 1988). Overall, the results indicated the strong reliability and convergent validity of our measures. Moreover, we assessed discriminant validity using Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion that the square root of the AVE exceed the correlations between all pairs of constructs. All measures for which an AVE was available meet the criterion (see Table 2).

4.2 Endogeneity

A potential concern for the empirical analysis is that FA performance may be endogeneous, which results in biased estimation of parameters (Jean et al. 2016). In addition, the use of cross-sectional survey data may potentially cause endogeneity (e.g., omitted variables, omitted selection including when sample suffers from self-selection or is non-representative, simultaneity, common method bias) and threaten estimate validity (Antonakis et al. 2010). To address the issue of endogeneity, instrument variable (IV) approach is used (Baum 2006) since it can address nearly all types of endogeneity issues (Jean et al. 2016). Marketing capabilities are suggested to be among the most important factors that directly influence FA performance (Morgan et al. 2009; Tan and Sousa 2015), and usually do not have a direct impact on exit decision (Kolev 2016). Therefore, we chose two of the marketing capabilities promotion capability (measured by rating the FA’s general capabilities in advertising and promotion, personal selling, and public relations, see Vorhies and Morgan 2003) and pricing capability (measured as the rate of the FA’s capability in pricing when compared to its major competitors, see Vorhies and Morgan 2003) as our two IVs. We ran diagnostic tests to ensure the appropriateness of the IVs: (1) the two IVs are highly related to performance (r = 0.31 and 0.21, respectively) but not significantly related to exit (r = − 0.01 and 0.07, respectively); (2) the two IVs are jointly statistically significant (F = 10.99, p < 0.01); (3) the Hausman test result cannot reject the hypothesis that performance is exogenous (Chi square = 0.88, p > 0.10). Therefore, we employ the binary logistic regression to yield unbiased estimates.

4.3 Hypothesis Testing

As the dependent variable in the model was binary, the Binary Logistics Regression was deemed appropriate to test our hypotheses. The model involved interaction effects, and therefore, the variables were previously mean-centered (Aiken et al. 1991). In addition, to generating robust results, we used all possible cross-products of the existing indicators as indicators of the two latent interaction factors in our model (Marsh et al. 2004). Moreover, to allow for a simultaneous comparison of different models, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted.

The results of the four different binary logistic regression models are reported in Table 3. We also reported the value and statistical significance of an explanatory variable’s marginal effect, which indicates the effect of a unit change in an explanatory variable on the dependent variable (Hoetker 2007; Wiersema and Bowen 2009). Model 1 contains only the control variables. Model 2 includes FA international performance, incremental innovation capability, radical innovation capability, and international experience. Model 3 adds the two two-way interactions. The final Model 4 further adds the two three-way interactions. The details appear in Table 3.

A steady decrease in the Log Likelihood value indicates that Model 4 has the least unexplained variation. This is also demonstrated by the fact that Pesudo R2 of Model 4 explains the largest amount of variance (Pesudo R2 = 0.36).

Not surprisingly, the results suggest that an FA’s international performance in a foreign market has a negative impact on the FA’s exit from the foreign market (B = − 1.18, p < 0.01), supporting the baseline hypothesis. Hypothesis 1 predicted that incremental innovation capability would attenuate the negative relationship between the FA’s international performance and the FA’s exit from the foreign market. The results of Model 3 confirm this prediction, as the coefficient for this interaction is significant and positive (B = 1.78, p < 0.05). Further evidence is provided in Fig. 2a, which shows that a significant negative relationship between an FA’s international performance and its exit from the foreign market holds for a low level of incremental innovation capability (simple slope: b = − 2.63, p < 0.01). However, when the level of incremental innovation capability is high, the negative impact of an FA’s international performance on its exit from the foreign market is not significant (b = 0.10, p > 0.10).

Moderating effects. a Moderating effect of incremental innovation capability on the relationship between FA performance and exit from the foreign market (hypothesis 1). b Moderating effect of radical innovation capability on the relationship between FA performance and exit from the foreign market (hypothesis 2). Notes: Near each line is the t-value for the corresponding slope. (**) means that the slope is statistically significant at 0.01 level; (ns) means that the slope is not statistically different from zero

Model 3 shows that radical innovation capability would strengthen the negative relationship between an FA’s international performance and the FA’s exit from the foreign market (B = − 2.01, p < 0.01), therefore refuting hypothesis 2. Further evidence is provided in Fig. 2b, showing that when the level of radical innovation capability is high, the FA’s international performance has a negative impact on its exit from the foreign market (simple slope: b = − 2.86, p < 0.01). However, when the level of radical innovation capability is low, the effect of the FA’s international performance on its exit from the foreign market becomes non-significant (b = 0.33, p > 0.10).

Hypothesis 3 proposes that the negative relationship between an FA’s international performance and the FA’s exit from a foreign market is strongest when both incremental innovation capability and international experience are low. This hypothesis is supported. Model 4 indicates a significant, negative three-way interaction between incremental innovation capability, international experience, and international performance (B = − 2.09, p < 0.05). In Fig. 3a, we present the results of this three-way interaction, using the simple slope of the FA’s international performance at one standard deviation above and below the means of the FA’s incremental innovation capability and international experience (see Aiken et al. 1991; Schmitz and Ganesan 2014). We find that, when incremental innovation capability is low (see Fig. 3a), the negative relationship of an FA’s international performance with the FA’s exit from a foreign market is stronger in the case of a low level of international experience (t = 1.77, p < 0.10). As a result, this negative relationship between the FA’s international performance and the exit decision when incremental innovation capability is low is weakened as the level of international experience increases.

Three-way interaction effects. a Moderating effect of incremental innovation capability and international experience on the relationship between FA performance and exit from the foreign market (hypothesis 3). b Moderating effect of radical innovation capability and international experience on the relationship between FA performance and exit from the foreign market (hypothesis 4)

Hypothesis 4 posits that the negative relationship between an FA’s international performance and the FA’s exit from a foreign market is strongest when both radical innovation capability and international experience are low. Although our empirical results in Model 4 reveal a significant and positive three-way interaction between radical innovation capability, international experience, and international performance (B = 1.71, p < 0.05), our hypothesis is refuted. To facilitate the interpretation of these findings, in Fig. 3b, we present the results of this three-way interaction, using the simple slope of the FA’s international performance at one standard deviation above and below the means of the FA’s radical innovation capability and international experience. Examining Fig. 3b, the results indicate that contrary to expectations this negative relationship is strongest when radical innovation is high and international experience is low. More specifically, this negative relationship between the FA’s international performance and the exit decision when radical innovation capability is high holds only for a low level of international experience (b = − 3.84, p < 0.01).

Regarding the control variables, PLC stage and FA age are found to be positively related to an FA’s exit from the foreign market. FA establishment method via M&A and organizational slack are negatively associated with an FA’s exit from the foreign market. All the other control variables show no significant influences on an FA’s exit from the foreign market (see Table 3).

5 Discussion and Implications

5.1 Theoretical Implications

The study supports our baseline hypothesis that an FA’s international performance has a negative impact on the FA’s exit decision from the foreign market. It also supports our argument that the impact of international performance on the firms’ exit decision is moderated by innovation capability and international experience. Thus, the following implications can be drawn from the study: Firstly, our research findings confirmed that innovation capability moderates the relationship between performance and exit decision. This is also consistent with the arguments from dynamic capabilities theory that dynamic capabilities such as innovation capability are effective moderators in their relationships with performance and strategies (e.g., Menguc et al. 2014). Therefore, our study contributes to the RBV literature by supporting the argument that, to explain different outcomes, not only the level of resources but also the capabilities in deploying the resources, are critical. This echoes the long-standing criticism of the RBV that it only emphasizes the possession of resources alone as a critical source of superior outcome, and ignores the subsequent configuration, integration, and leverage of the resources (i.e., capabilities) that can be transformed into desirable outcomes (Sirmon et al. 2007). The insight from this study is that in subsequently managing (i.e., configuring/deploying, integrating, and leveraging) the resources, capabilities should be treated as equally, if not more, important than resources themselves when explaining different strategic outcomes. In this sense, the RBV can be advanced by treating capabilities as moderators instead of independent variables, thereby distinguishing capabilities from resources and better reflecting their function of resource deployment.

In addition, the interplays between innovation capabilities and international experience are shown to influence the performance-exit relationship, thereby supporting the argument that there is interaction between strategic resources (Crook et al. 2008). This also echoes another criticism of the RBV that the way in which managers use strategic actions to leverage the strategic resources (i.e., the issue of strategy implementation) is largely ignored by extant research (Crook et al. 2008). Therefore, the RBV can be further advanced with the idea of resource orchestration, by explicitly including variables/factors which reflect managers’ behavioral differences in managing resources to address the issue of strategy implementation, thereby better explaining different firm outcomes.

Secondly, our research findings reported that two types of innovation capability have opposite contingent effects on the performance-exit relationship. This is somewhat surprising but insightful in advancing our research on innovation capability. Specifically, although we confirmed that incremental innovation capability attenuates the performance–exit relationship, we refuted the same effect for radical innovation capability. This means that MNC managers are more likely to exit a poorly-performing FA with high versus low radical innovation. A possible explanation for this surprising result could be related to MNC managers’ low time tolerance, since the key characteristic distinguishing radical innovation capability from incremental innovation capability lies in its long-time orientation and focus on building future competitive advantage (Crossan and Apaydin 2010; Tushman and O’Reilly 1996). As a result, this finding may reflect the fact that when deciding on whether to exit a poorly-performing FA business from the foreign market, MNC managers tend to have a low tolerance of time. In this case, a poorly-performing FA with high radical innovation capability is more likely to exit because the managers’ perception is that it takes a relatively long time to turn it around. In addition, the formation and implementation of radical innovation strategy is substantially costly and risky (Velu 2015), and as a result MNC managers may be less willing to commit large resources to a poorly performing FA. This may also lead to the firm’s decision to divest the poorly-performing FA from the foreign market.

Thirdly, our research findings further indicate that it is necessary to differentiate the two types of innovation capability, as they may have different or even opposite influence on the same relationship. This also echoes the Slater et al. (2014) argument that a big limitation of extant research findings on innovation capability is that they did not distinguish between incremental and radical innovation. In this sense, only when we examine the differential influences of the two types of innovation capability, can we see the full picture of the proposed relationships and provide a more comprehensive answer to our research question. In addition, as an outpouring of studies has examined the topic of organizational ambidexterity in pursuing both types of innovation (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013), the difference between incremental innovation capability and radical innovation capability has been well acknowledged (Crossan and Apaydin 2010). However, whether and how the difference between the two types of innovation capabilities, especially when interacting with other factors, will lead to different strategic decisions or performance implications, remains an underdeveloped area (e.g., Menguc et al. 2014). While this study tried to address this gap in the literature, more research in this area is needed to generate new insights into the advancement of theories in dynamic capabilities and innovation.

Fourthly, our research findings show that international experience influences the moderating effects of innovation capabilities on the performance-exit relationship. This study suggests that the effectiveness of incremental innovation capability in reducing the probability of exiting a poorly-performing FA is further strengthened by the MNC’s international experience. This is consistent with the recent argument for resource orchestration that there are interactions between firms’ strategic resources (Sirmon et al. 2011). International experience plays an important role in effectively leveraging an FA’s incremental innovation capability for innovative strategy and implementing it, thereby achieving complementarity.

Lastly, our findings show that, in the case of high radical innovation capability, international experience weakens the relationship between performance and foreign exit. Consistent with our previous argument, one possible explanation is that, as an FA with high radical innovation capability takes a relatively long time to improve its current poor performance, managers are more likely to make the decision to exit it from the foreign market. However, high international experience reduces the likelihood of an exit decision, because it allows managers to understand better the relatively long time for a poorly-performing FA with high radical innovation capability to improve performance, and therefore is likely to give the FA a longer tolerance time. In addition, international experience gives managers confidence in his ability to implement an optimal innovation strategy. In this case, an exit decision is less likely to be made. This once again demonstrates the presence of interaction between strategic resources. Therefore, it is necessary for RBV theorists to incorporate the idea of resource orchestration and consider how interactions between strategic resources shape a firm’s performance and strategic decision.

5.2 Managerial Implications

Firstly, our results suggest that developing a high level of incremental innovation capability will not only generally contribute to an FA’s survival, but also to some extent, prevent an FA from exiting a foreign market when it yields poor performance. Namely, a high level of incremental innovation capability can leverage the negative influence of performance on an FA’s survival. In this case, it is very worthwhile for an FA to strive for high incremental innovation capability, which is beneficial to hold competitive advantage in the foreign market and helps the FA to gain a second chance to operate in the current foreign market.

Secondly, our results show that an FA’s radical innovation capability strengthens the relationship between FA performance and exit decision. As explained above, MNC managers’ low time tolerance of poor performance seems to be a possible explanation. If this is the case, this is not very beneficial to the MNC’s long-term benefit, considering that a high level of radical innovation capability is very likely to help the poorly-performing FA to break the competitive structure and become the future market leader (Tushman and O’Reilly 1996). Therefore, it may be wiser for MNC mangers to give a longer time for an FA with high radical innovation capability to recover, instead of making a hasty exit decision when the FA yields poor performance.

Lastly, our results show that firm international experience plays an important role in foreign exit decisions. Managers are encouraged to increase their level of international experience. As international experience cannot be suddenly obtained, MNCs could consider recruiting managers with more international experience to participate in the strategic decision making.

5.3 Limitations and Future Research Directions

A few limitations of this study need to be acknowledged in the interests of advancing future research. Firstly, our sample is focused on Chinese OFDI firms. In this case, extending our research findings to a larger research context should only be done with caution. Thus, future studies may test our model in a different emerging MNCs context to check whether our research findings have external validity.

Secondly, cross-sectional survey data is used, which cannot explain the dynamic processes of how the interacting effects of performance, innovation capabilities, and international experience on the exit decision change over time. Therefore, future research might use longitudinal data to better capture the dynamism of the proposed model. The use cross-lagged panel analysis would be a good way forward as it allows examination of causality in longitudinal data.

Thirdly, the literature provides many other measurements of international performance. In this study we used a subjective measure of international performance by asking managers their satisfaction level. This takes into consideration the heterogeneous aspirational performance of different MNCs and therefore can better capture whether the FA’s performance objective has been achieved, which is a more precise trigger of decision behavior (see Cyert and March 1963). However, future studies can complement such measurement by obtaining some objective data.

Lastly, future studies should explore the use of additional theories to explain the firm’s exit decision. The use of theories such as transaction cost economics (TCE), resource advantage theory, and upper echelon theory fits well with foreign exit studies and should facilitate the development of new conceptual models to advance knowledge in the field. For instance, the use of upper echelon theory would encourage us to focus more on the characteristics of the manager to explain the firm’s strategic decisions. This is consistent with the view that the manager and the choices exercised by the individual actors when making strategic decisions are paramount (Child 1972; Finkelstein et al. 2009). In this case, while the focus of this study is on the differential moderating effects of international experience and the two types of innovation capability (i.e., incremental and radical innovation capability) on the FA performance–FA exit relationship, in the future, the model could be expanded to include other relevant moderators that focus on the manager such as managers’ escalation of commitment and managers’ self-interests.

References

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Anderlini, J. (2015). China to become world’s biggest overseas investor by 2020 (Financial Times). London: Pearson PLC.

Andersson, U., & Forsgren, M. (1996). Subsidiary embeddedness and control in the multinational corporation. International Business Review, 5(5), 487–508.

Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. W. (2010). Managing innovation paradoxes: Ambidexterity lessons from leading product design companies. Long Range Planning, 43(1), 104–122.

Antonakis, J., Bendahan, S., Jacquart, P., & Lalive, R. (2010). On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 1086–1120.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94.

Baker, W. E., & Sinkula, J. M. (2007). Does market orientation facilitate balanced innovation programs? An organizational learning perspective. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 24(4), 316–334.

Barkema, H. G., Bell, J. H. J., & Pennings, J. M. (1996). Foreign entry, cultural barriers, and learning. Strategic Management Journal, 17(2), 151–166.

Barkema, H. G., & Vermeulen, F. (1997). What differences in the cultural backgrounds of partners are detrimental for international joint ventures? Journal of International Business Studies, 28(4), 845–864.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Barney, J. B. (2001). Is the resource-based “View” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 41–56.

Baum, C. F. (2006). An introduction to modern econometrics using stata. College Station: Stata Press Publication.

Belderbos, R., & Zou, J. (2009). Real options and foreign affiliate divestments: A portfolio perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(4), 600–620.

Benito, G. R. G., & Welch, L. S. (1997). De-internationalization. Management International Review, 37(S2), 7–25.

Berry, H. (2013). When do firms divest foreign operations? Organization Science, 24(1), 246–261.

Boddewyn, J. J. (1979). Foreign divestment: Magnitude and factors. Journal of International Business Studies, 10(1), 21–27.

Boddewyn, J. J. (1985). Theories of foreign direct investment and divestment: A classificatory note. Management International Review, 25(1), 57–65.

Boddewyn, J. J., & Torneden, R. (1973). U. S. Foreign divestment: A preliminary survey. Columbia Journal of World Business, 8(2), 25–29.

Bouquet, C., & Birkinshaw, J. (2008). Weight versus voice: How foreign subsidiaries gain attention from corporate headquarters. Academy of Management Journal, 51(3), 577–601.

Brouthers, K. D., Nakos, G., & Dimitratos, P. (2015). SME entrepreneurial orientation, international performance, and the moderating role of strategic alliances. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(5), 1161–1187.

Calantone, R. J., Cavusgil, S. T., & Zhao, Y. (2002). Learning orientation, firm innovation capability, and firm performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 31(6), 515–524.

Casillas, J. C., Moreno, A. M., & Acedo, F. J. (2012). Path dependence view of export behaviour: A relationship between static patterns and dynamic configurations. International Business Review, 21(3), 465–479.

Cavusgil, S. T., & Zou, S. (1994). Marketing strategy–performance relationship: An investigation of the empirical link in export market ventures. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 1–21.

Cefis, E., & Marsili, O. (2005). A matter of life and death: Innovation and firm survival. Industrial and Corporate Change, 14(6), 1167–1192.

Cefis, E., & Marsili, O. (2011). Born to flip. Exit decisions of entrepreneurial firms in high-tech and low-tech industries. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 21(3), 473–498.

Chang, S.-J., Van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2010). From the editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2), 178–184.

Child, J. (1972). Organizational structure, environment and performance: The role of strategic choice. Sociology, 6(1), 1–22.

Chung, C. C., Lee, S.-H., & Lee, J.-Y. (2013). Dual-option subsidiaries and exit decisions during times of economic crisis. Management International Review, 53(4), 555–577.

Collis, D. J. (1991). A resource-based analysis of global competition: The case of the bearings industry. Strategic Management Journal, 12(S1), 49–68.

Crook, T. R., Jr., Ketchen, D. J., Jr., Combs, J. G., & Todd, S. Y. (2008). Strategic resources and performance: A meta-analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 29(11), 1141–1154.

Crossan, M. M., & Apaydin, M. (2010). A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1154–1191.

Cyert, R. M., & March, J. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Dai, L., Eden, L., & Beamish, W. P. (2013). Place, space, and geographical exposure: Foreign subsidiary survival in conflict zones. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(6), 554–578.

Dai, L., Eden, L., & Beamish, P. W. (2017). Caught in the crossfire: Dimensions of vulnerability and foreign multinationals’ exit from war-afflicted countries. Strategic Management Journal, 38(7), 1478–1498.

Dawson, J. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19.

Day, G. S., & Wensley, R. (1988). Assessing advantage: A framework for diagnosing competitive superiority. Journal of Marketing, 52(2), 1–20.

Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. (2004). Joint venture performance revisited: Japanese foreign subsidiaries worldwide. Management International Review, 44(1), 69–91.

Deng, Z., Guo, H., Zhang, W., & Wang, C. (2014). Innovation and survival of exporters: A contingency perspective. International Business Review, 23(2), 396–406.

Dixit, A. (1989). Entry and exit decisions under uncertainty. Journal of Political Economy, 97(3), 620–638.

Dow, D., & Larimo, J. (2009). Challenging the conceptualization and measurement of distance and international experience in entry mode choice research. Journal of International Marketing, 17(2), 74–98.

Duhaime, I. M., & Grant, J. H. (1984). Factors influencing divestment decision-making: Evidence from a field study. Strategic Management Journal, 5(4), 301–318.

Efrat, K., & Shoham, A. (2012). Born global firms: The differences between their short- and long-term performance drivers. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 675–685.

Finkelstein, S., Hambrick, D. C., & Cannella, A. A. (2009). Strategic leadership: Theory and research on executives, top management teams, and boards. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Fowler, F. J., Jr. (1995). Improving survey questions: Design and evaluation (Vol. 38). London: Sage Publications.

Franco, A. M., Sarkar, M. B., Agarwal, R., & Echambadi, R. (2009). Swift and smart: The moderating effects of technological capabilities on the market pioneering—firm survival relationship. Management Science, 55(11), 1842–1860.

Fredrickson, J. W., & Mitchell, T. R. (1984). Strategic decision processes: Comprehensiveness and performance in an industry with an unstable environment. Academy of Management Journal, 27(2), 399–423.

Gaur, A. S., & Lu, J. W. (2007). Ownership strategies and subsidiary survival: Impacts of institutional distance and experience. Journal of Management, 33(1), 84–110.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T. B., Cooper, A. C., & Woo, C. Y. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(4), 750–783.

Giovannetti, G., Ricchiuti, G., & Velucchi, M. (2011). Size, innovation and internationalization: A survival analysis of italian firms. Applied Economics, 43(12), 1511–1520.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Hambrick, D. C., & Snow, C. C. (1977). A contextual model of strategic decision making in organizations. Academy of Management Proceedings, 1977(1), 109–112.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1993). Organizational ecology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

He, X., Brouthers, K. D., & Filatotchev, I. (2013). Resource-based and institutional perspectives on export channel selection and export performance. Journal of Management, 39(1), 27–47.

Hennart, J.-F., Dong-Jae, K., & Ming, Z. (1998). The impact of joint venture status on the longevity of Japanese stakes in U.S. manufacturing affiliates. Organization Science, 9(3), 382–395.

Hill, C. (2012). The china challenge: Why mergers and acquisitions often fail. China Daily Mail. https://chinadailymail.com/2012/05/20/the-china-challenge-why-mergers-and-acquisitions-often-fail/.

Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., Sirmon, D. G., & Trahms, C. A. (2011). Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating value for individuals, organizations, and society. Academy of Management Executive, 25(2), 57–75.

Hoetker, G. (2007). The use of logit and probit models in strategic management research: Critical issues. Strategic Management Journal, 28(4), 331–343.

Hortinha, P., Lages, C., & Filipe Lages, L. (2011). The trade-off between customer and technology orientations: Impact on innovation capabilities and export performance. Journal of International Marketing, 19(3), 36–58.

Hughes, M., Martin, S. L., Morgan, R. E., & Robson, M. J. (2010). Realizing product-market advantage in high-technology international new ventures: The mediating role of ambidextrous innovation. Journal of International Marketing, 18(4), 1–21.

Hultman, M., Katsikeas, C. S., & Robson, M. J. (2011). Export promotion strategy and performance: The role of international experience. Journal of International Marketing, 19(4), 17–39.

Jean, R.-J. B., Deng, Z., Kim, D., & Yuan, X. (2016). Assessing endogeneity issues in international marketing research. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 483–512.

Kang, J., Lee, J., & Ghauri, P. (2017). The interplay of Mahalanobis distance and firm capabilities on MNC subsidiary exits from host countries. Management International Review, 57(3), 379–409.

Karna, A., Richter, A., & Riesenkampff, E. (2016). Revisiting the role of the environment in the capabilities–financial performance relationship: A meta-analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 37(6), 1154–1173.

Kim, T.-Y., Delios, A., & Xu, D. (2010). Organizational geography, experiential learning and subsidiary exit: Japanese foreign expansions in china, 1979–2001. Journal of Economic Geography, 10(4), 579–597.

Kim, Y.-C., Lu, J. W., & Rhee, M. (2012). Learning from age difference: Interorganizational learning and survival in Japanese foreign subsidiaries. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(8), 719–745.

Klepper, S., & Simons, K. L. (2000). Dominance by birthright: Entry of prior radio producers and competitive ramifications in the U.S. television receiver industry. Strategic Management Journal, 21(10/11), 997–1016.

Koch, P. T., Koch, B., Menon, T., & Shenkar, O. (2016). Cultural friction in leadership beliefs and foreign-invested enterprise survival. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(4), 453–470.

Kogut, B. (1983). Foreign direct investment as a sequential process. In C. P. Kindleberger & D. Andretsch (Eds.), The multinational corporation in the 1980s (pp. 38–56). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kolev, K. D. (2016). To divest or not to divest: A meta-analysis of the antecedents of corporate divestitures. British Journal of Management, 27(1), 179–196.

Kotabe, M., & Ketkar, S. (2009). Exit Strategies. In M. Kotabe & K. Helsen (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of international marketing. London: Sage Publications.

Kraaijenbrink, J., Spender, J.-C., & Groen, A. J. (2010). The resource-based view: A review and assessment of its critiques. Journal of Management, 36(1), 349–372.

Lages, L. F., Jap, S. D., & Griffith, D. A. (2008). The role of past performance in export ventures: A short-term reactive approach. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(2), 304–325.

Lee, H., Kelley, D., Lee, J., & Lee, S. (2012). SME survival: The impact of internationalization, technology resources, and alliances. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(1), 1–19.

Levinthal, D. A., & March, J. G. (1993). The myopia of learning. Strategic Management Journal, 14(S2), 95–112.

Li, J. (1995). Foreign entry and survival: Effects of strategic choices on performance in international markets. Strategic Management Journal, 16(5), 333–351.

Lu, J., Liu, X., Wright, M., & Filatotchev, I. (2014). International experience and fdi location choices of Chinese firms: The moderating effects of home country government support and host country institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(4), 428–449.

Madsen, P. M., & Desai, V. (2010). Failing to learn? The effects of failure and success on organizational learning in the global orbital launch vehicle industry. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 451–476.

Markides, C. C., & Berg, N. A. (1992). Good and bad divestment: The stock market verdict. Long Range Planning, 25(2), 10–15.

Marsh, H. W., Wen, Z., & Hau, K.-T. (2004). Structural equation models of latent interactions: Evaluation of alternative estimation strategies and indicator construction. Psychological Methods, 9(3), 275–300.

Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (2000). Closure and divestiture by foreign entrants: The impact of entry and post-entry strategies. Strategic Management Journal, 21(5), 549–562.

Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (2002). The survival of new domestic and foreign-owned firms. Strategic Management Journal, 23(4), 323–343.

McDermott, M. C. (2010). Foreign divestment: The neglected area of international business? International Studies of Management and Organization, 40(4), 37–53.

Menguc, B., Auh, S., & Yannopoulos, P. (2014). Customer and supplier involvement in design: The moderating role of incremental and radical innovation capability. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(2), 313–328.

Meyer, K. E., Estrin, S., Bhaumik, S. K., & Peng, M. W. (2009). Institutions, resources, and entry strategies in emerging economies. Strategic Management Journal, 30(1), 61–80.

Meyer, K. E., & Gelbuda, M. (2006). Process perspectives in international business research in CEE. Management International Review, 46(2), 143–164.

Morgan, N. A., Vorhies, D. W., & Mason, C. H. (2009). Market orientation, marketing capabilities, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30(8), 909–920.

Morris, M. W., & Moore, P. C. (2000). The lessons we (don’t) learn: Counterfactual thinking and organizational accountability after a close call. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(4), 737–765.

Mudambi, R., & Zahra, S. A. (2007). The survival of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(2), 333–352.

Nadolska, A., & Barkema, H. G. (2007). Learning to internationalise: The pace and success of foreign acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(7), 1170–1186.

Ndofor, H. A., Sirmon, D. G., & He, X. (2015). Utilizing the firm’s resources: How TMT heterogeneity and resulting faultlines affect TMT tasks. Strategic Management Journal, 36(11), 1656–1674.

Newbert, S. L. (2007). Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strategic Management Journal, 28(2), 121–146.

Nielsen, B. B., & Nielsen, S. (2011). The role of top management team international orientation in international strategic decision-making: The choice of foreign entry mode. Journal of World Business, 46(2), 185–193.

O’Brien, J., & Folta, T. (2009). Sunk costs, uncertainty and market exit: A real options perspective. Industrial and Corporate Change, 18(5), 807–833.

OECD (2008). OECD benchmark definition of foreign direct investment (4th ed.). OECD Publications.

Oehme, M., & Bort, S. (2015). SME internationalization modes in the german biotechnology industry: The influence of imitation, network position, and international experience. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(6), 629–655.

O’Reilly, C. A., III, & Tushman, M. L. (2004). The ambidextrous organization. Harvard Business Review, 82(4), 74–81.

O’Reilly, C. A., III, & Tushman, M. L. (2013). Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 324–338.