Abstract

Background

D2 total gastrectomy combined with splenectomy or pancreaticosplenectomy reportedly increases morbidity and mortality. Totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG) for advanced gastric cancer (AGC) remains controversial because of its technical difficulties and lack of long-term results. We determined the feasibility and safety of TLTG for AGC.

Methods

A single-institution retrospective study was conducted. Ninety-two consecutive AGC patients who underwent radical TLTG were enrolled. The primary end point was morbidity. The patients were observed for 3 years following TLTG. We assessed short-term surgical and long-term outcomes, including 3-year overall survival rates (3yOS) and 3-year recurrence-free survival rates (3yRFS).

Results

Early and late morbidities (Clavien–Dindo grade ≥3) were 26.1 and 6.5 %, respectively. Operative time, estimated blood loss, number of dissected lymph nodes, and postoperative hospital stay were 444 (278–694) min, 100 (0–2267) g, 48 (16–89), and 23 (9–136) days, respectively, and 3yOS and 3yRFS rates were 70.7 and 60.9 %, respectively. Factors associated with postoperative complications and 3yOS were operative time [OR 1.011 (1.006–1.017), p < 0.01] and cancer recurrence within 3 years [HR 312.191 (1.126–86573.245], p = 0.045], respectively. 3yRFS was associated with tumor size (≥50 mm) [HR 10.325 (1.328–80.289), p = 0.026], pathological N factor ≥2 [HR 3.188 (1.196–8.495), p = 0.02], and postoperative pancreatic fistula combined with intra-abdominal abscesses Clavien–Dindo grade ≥2; [HR 3.670 (1.440–9.351), p = 0.006].

Conclusions

TLTG for AGC is sufficiently feasible and safe from both surgical and oncological point of view.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common malignant tumor and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. Surgical resection remains the only curative treatment option, and regional lymphadenectomy is recommended as part of radical gastrectomy [2]. According to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Cancer, D2 total gastrectomy is recommended for advanced proximal gastric cancer [3]; however, D2 lymphadenectomy combined with splenectomy or pancreaticosplenectomy has been reported to increase morbidity and mortality [4–6]. Therefore, the practical importance of station 10 lymph node (LN) dissection and splenectomy in D2 total gastrectomy is controversial [7–9].

Laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG) has been increasingly performed as a minimally invasive surgical approach that provides significant advantages for short-term outcomes as opposed to open surgical procedures for the early gastric cancer (EGC) patients [10, 11]. However, LG, including totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG), for advanced gastric cancer (AGC) remains controversial because of its technical difficulties and lack of long-term results [4, 12–14].

We started TLTG for AGC in 1997 [15] and have established a stable and robust methodology, including splenic hilar lymph node (SHLN) dissection. We herein determined the technical and oncological feasibility as well as safety of TLTG for AGC.

Materials and methods

Patients

We conducted a single-institution retrospective study between January 2007 and May 2012. The patient selection process is summarized in Fig. 1. During this period, 855 consecutive primary gastric cancer patients for whom surgical treatment was applicable were referred to our division. Of these patients, 234 patients with gastric cancer infiltrating into the upper third of stomach underwent total gastrectomy. Ninety-two consecutive AGC patients (cStage IB, II, or III) who underwent radical TLTG were enrolled. A minimally invasive approach was also used for all the 234 patients, except for the one patient who underwent open total gastrectomy. All patients were evenly offered open, laparoscopic, and robotic surgery. These patients were observed for 3 years following surgical resection; short-term surgical outcomes, including operative time, estimated blood loss, postoperative complications, length of postoperative hospital stay, number of harvested LNs, and clinicopathological characteristics, as well as long-term outcomes, including 3-year overall survival (3yOS) and 3-year recurrence-free survival (3yRFS) rates, were assessed. The primary end point was morbidity. Postoperative complications for grades greater than II or III determined according to the Clavien–Dindo (CD) classification were recorded [16, 17]. The types of postoperative complications were classified in accordance with the Japan Clinical Oncology Group Postoperative Complication Criteria according to CD ver. 2.0 [18]. Total operative time was the time from the start of the abdominal incision to the completion of wound closure. Blood loss was estimated by weighing suctioned blood and gauze pieces absorbing blood. Survival was estimated from the date of initial diagnosis of gastric cancer. All operations were supervised by I.U. All the participating surgeons had previously performed ≥30 LGs. Details of indications for radical gastrectomy, assessment of physical function, operative procedures, and perioperative management in radical gastrectomy, extent of gastric resection and LN dissection, and postoperative chemotherapy as well as oncological follow-up have been previously reported [4, 13, 19]. All patients were completely involved in the decision-making process, and informed consent was obtained from them. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fujita Health University.

Splenic hilar LN dissection in TLTG

TLTG followed by intra-corporeal anastomosis using linear staplers was performed using the 6-port system. Gastric resection combined with radical lymphadenectomy, except for SHLN dissection, was performed in the same manner as that of previously reported [20–22].

Extent of splenic hilar LN dissection

Regarding the extent of SHLN dissection, D2 lymphadenectomy combined with distal pancreaticosplenectomy (D2 + PS) was performed in patients with tumors infiltrating into the pancreatic body or tail. D2 lymphadenectomy combined with splenectomy (D2 + S) was performed in patients with LN metastasis at the station 11d or 10 or in those with greater curvature invasion. Spleen-preserving D2 lymphadenectomy (D2-S) was performed in patients with tumor depths ≥cT3 without LN metastasis at the station 11d or 10, whereas D2 lymphadenectomy with preservation of station 10 LNs and the spleen (D2-10) was performed in patients without greater curvature invasion and with tumor depths ≤cT2.

Operating procedures

Additional care to control the extent of SHLN dissection in TLTG was given to (1) the layer on the fusion fascia at the infrapancreatic border of the pancreatic tail, (2) the layer on the subretroperitoneal fascia on the left diaphragmatic crus around the upper pole of the spleen, and (3) the outermost layer of the splenic artery (Fig. 2). Using these layers, the aforementioned four different types of SHLN dissection could easily be performed. Procedural details are summarized in Supplemental Video clips 1–3.

Type of anastomosis

Following total gastrectomy, intra-abdominal Roux-en-Y anastomosis was performed mostly using functional end-to-end anastomosis with linear staplers [15, 23], whereas intra-thoracic Roux-en-Y anastomosis was performed using the overlap method [24]. OrVilTM (Covidien, Mansfield, MA) was used in some cases according to the operating surgeons’ preference.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Independent continuous variables were compared by the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test, and categorical variables were compared by the χ [2] (Chi-square) test or Fisher’s exact test. Univariate Chi-square test and multivariate logistic regression analysis were used to determine the factors associated with postoperative complications. Long-term outcomes were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier methods with the log-rank test and Cox regression. Univariate analyses were performed for all potential confounding variables and effect modifiers. Considering the relatively small sample size, all variables with a significant level of p < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were included as independent variables. Data were expressed as the median (range) or odds/hazard ratio [OR/HR; (95 % confidence interval)], unless otherwise noted. A p value of < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant. A Bonferroni correction factor was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the 92 patients, 61 (66.3 %) were male. Age and body mass index (BMI) were 65 (34–88) years and 21.7 (15.0–32.4) kg/m2, respectively. Fifty-one (55.4 %) patients had American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status (ASA-PS) comorbidities > Class 1. Nineteen (20.7 %) patients had histories of laparotomy. Tumor size was 50 mm. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) and adjuvant chemotherapy were used in 54 (58.7 %) and 64 (69.6 %) patients, respectively.

Surgical outcomes and short-term postoperative courses

Surgical outcomes and short-term postoperative courses are summarized in Table 1. Operative time, estimated blood loss, and number of dissected LNs were 444 min, 100 g, and 48, respectively. Regarding the extent of SHLN dissection, D2-10, D2-S, D2 + S, and D2 + PS were performed in 5, 36, 32, and 19 patients, respectively. Duration of postoperative hospital stay was 23 days. There was no conversion to laparotomy or mortality in this series.

Early and late postoperative complications

Postoperative complications are summarized in Table 2. Within 30 days following TLTG, 24 (26.1 %) patients developed ≥ one complication classified as CD grade ≥III, including pancreatic fistula in 11 (12.0 %), anastomotic leakage in 8 (8.7 %), and intra-abdominal abscess in 4 (4.3 %). There was no anastomotic stenosis. Late complications occurring after >30 days following TLTG classified as CD grade ≥III were observed in six (6.5 %) patients, three (3.3 %) of whom suffered from internal hernia requiring laparoscopic repair.

Factors associated with postoperative complications

Univariate analyses showed that BMI, clinical N factor of ≥2, use of NAC, operative time, estimated blood loss, and pancreaticosplenectomy were significant factors for early morbidity (CD grade ≥III). However, operative time [OR 1.011 (1.006–1.017); p < 0.01] was the only significant independent risk factor in multivariate analyses.

Differences in short-term outcomes according to the extent of splenic hilar lymphadenectomy

Greater extent of SHLN dissection led to longer operative time (p = 0.010) and more frequent postoperative complications (CD grade ≥III; p = 0.034), including pancreatic fistula (p < 0.001) (Table 3). Particularly, combined splenic resection increased operative time (p = 0.015) and pancreatic fistula (p = 0.002). Addition of pancreaticosplenectomy induced pancreatic fistula even more frequently than that induced by splenectomy alone (p = 0.001). No significant differences were seen in the number of dissected LNs and anastomotic leakage among the groups.

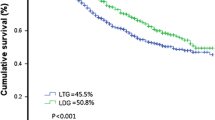

Three-year long-term outcomes

The 3yOS rates according to the clinical JCGC stages of cIB, cII, and cIII were 67.4, 68.2, and 67.6 %, respectively, and the 3yRFS rates were 70.8, 56.5, and 59.1 %, respectively. The 3yOS rates according to the pathological JCGC stages of pCR, pI, pII, and pIII were 100.0, 93.8, 72.7, and 58.7 %, respectively (Fig. 3), and the 3yRFS rates were 100.0, 100.0, 66.7, and 39.0 %, respectively. Peritoneal dissemination was the most frequent type of recurrence. Of the 36 patients with any type of cancer recurrence ≤3 years after TLTG, peritoneal dissemination was detected in 24 (66.7 %) patients. Liver and distant LN metastasis occurred in seven (19.4 %) and five (13.9 %) patients, respectively. Here, no local recurrence and loco-regional LN metastasis occurred.

Factors associated with 3-year long-term outcomes

Univariate analyses revealed that tumor size (≥50 mm, p = 0.023), pathological responder to NAC (grade ≥1b, p = 0.007), pathological T factor (≥SE, p < 0.001), pathological N factor (≥2, p = 0.026), pathological stage (≥II, p = 0.022), morbidity (CD grade ≥II, p = 0.012), total early postoperative local complications (CD grade ≥II, p = 0.006), postoperative pancreatic fistula combined with intra-abdominal abscesses (CD grade ≥II, p = 0.006), and longer hospital stay (≥25 days, p = 0.011) were associated with 3yOS, whereas the multivariate analysis demonstrated that cancer recurrence ≤3 years was the only significant factor associated with 3yOS [HR 312.191 (1.126–86573.245); p = 0.045]. Univariate analyses showed that tumor size (≥50 mm, p = 0.009), pathological responder to NAC (grade ≥1b, p = 0.005), use of adjuvant chemotherapy (p = 0.025), pathological T factor (≥SE, p < 0.001), pathological N factor (≥2, p < 0.001), pathological stage (≥II, p = 0.001), total early postoperative local complications (CD grade ≥II, p = 0.01), and postoperative pancreatic fistula combined with intra-abdominal abscesses (CD grade ≥II, p = 0.022) were associated with 3yRFS, whereas the multivariate analysis demonstrated that tumor size ≥50 mm [HR 10.325 (1.328–80.289), p = 0.026], pathological N factor of ≥2 [HR 3.188 (1.196–8.495), p = 0.02], and postoperative pancreatic fistula combined with intra-abdominal abscesses CD grade ≥II [HR 3.670 (1.440–9.351), p = 0.006] were significant factors associated with 3yRFS. Since postoperative pancreatic fistula combined with intra-abdominal abscess formations (CD grade ≥II) took place more frequently in the D2 + PS group than in the other groups (10/19 in D2 + PS vs. 11/73 in the others p = 0.0013), and most of the patients (17/19) in the D2 + PS group had pStage II or III disease, extent of SHLN dissection and pathological stage might confound the association between postoperative pancreatic fistula combined with intra-abdominal abscess formations and 3yRFS. To eliminate the influence of these confounding variables, this association was further examined in the patients who underwent D2 + PS stratified with the pathological stage. However, differences in 3yRFS of the patients with or without these complications were not sufficiently evaluated because of the limited sample size. The extent of SHLN dissection and late postoperative complications were not associated with the 3-year long-term outcomes.

Discussion

The study clearly demonstrates technical and oncological feasibility and safety of TLTG for AGC with three major findings

First, early morbidity (26.1 %) and mortality (0 %) of TLTG for AGC were quite acceptable considering that morbidities in laparoscopic (mostly for EGC) and open total gastrectomy currently range from 4.9 to 33.3 % [25–27] and 5.4–37.2 % [25, 28–31], respectively, and mortality after gastric cancer surgery has been approximately 1 % [19]. Operative time [444 (278–694) min], estimated blood loss [100 (0–2267) g], and number of dissected LNs [48 (16–89)], and postoperative hospital stay [23 (9–136) days] were also sufficient considering the results of previous studies [14, 25–27]. These data suggest the technical feasibility of our method. With regard to late complications, internal hernia occurred in up to three (3.3 %) patients; this appears paradoxical because an advantage of laparoscopic surgery is that little intra-abdominal adhesion is induced, leading to the induction of internal hernia through residual open mesenteric defects [32]. All of the mesenteric defects developing after TLTG, including Petersen’s defect, jejunojejunal mesenteric defect, and esophageal hiatus, should be closed using unabsorbable sutures [33].

Second, the 3yOS and 3yRFS rates of all the enrolled patients were 70.7 and 60.9 %, respectively. Pathological stage-stratified 3yOS and 3yRFS in this study were at least comparable with those in previous reports from high-volume centers, although pathological stage may be considerably affected by the effect of NAC [6, 29, 34–37]. These results suggest the oncological safety of our technique. According to multivariate analysis, the most important factor associated with 3yOS was tumor recurrence. Thus, to remove the influence of tumor recurrence on survival, 3yRFS was assessed. Not only oncological factors, including tumor size (≥50 mm) and pathological N factor of ≥2, but also a surgical factor, including postoperative pancreatic fistula, combined with intra-abdominal abscesses (CD grade ≥II) were associated with RFS, although stratified analyses failed to verify the association between these postoperative complications and RFS at least partly because of the limited sample size of the present study. These results were consistent with those of our previous report that postoperative local complications may deteriorate long-term outcomes [21], suggesting the oncological and surgical importance of preventing pancreatic fistula and intra-abdominal abscess. Use of a surgical robot in TLTG, which we previously determined was helpful in reducing local complications, including pancreatic fistula [19], is promising.

Third, our SHLN dissection technique appears to be versatile because it could be easily used for the four different extents of SHLN dissection. Here, multivariate analysis revealed that operative time was the only significant factor associated with postoperative complications. Operative time, morbidity, and pancreatic fistula increased with increasing extent of SHLN dissection. Therefore, the extent of SHLN dissection should be appropriately attenuated if this is allowed by oncological factors. At present, according to the latest Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4) [38], complete clearance of station 10 nodes by splenectomy should still be considered for potentially curable T2–T4 tumors invading the greater curvature of the upper stomach. However, in patients with T2–4/N0–2/M0 gastric cancer not invading the greater curvature, the JCOG0110 trial demonstrated that prophylactic splenectomy should be avoided to improve operative safety and survival [2, 39].

There were some limitations to this study. This was a single-institution retrospective study, the sample size was relatively small, and the observation period was relatively short. Therefore, the data may be biased and the overall results should be cautiously interpreted. A large multicenter prospective cohort study is warranted to determine whether our results are replicable.

In conclusion, TLTG for AGC was considerably feasible and safe from both surgical and oncological perspective. Our principle for SHLN dissection, in which the extent of dissection could be easily controlled, may be useful in reducing the risk of postoperative complications considering oncological validity.

Abbreviations

- TLTG:

-

Totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy

- AGC:

-

Advanced gastric cancer

- EGC:

-

Early gastric cancer

- LG:

-

Laparoscopic gastrectomy

- LN:

-

Lymph node

- SHLN:

-

Splenic hilar lymph node

- 3yOS:

-

Three-year overall survival rates

- 3yRFS:

-

Three-year recurrence-free survival rates

- D2-10:

-

D2 lymphadenectomy with preservation of station 10 lymph nodes and spleen

- D2-S:

-

Spleen-preserving D2 lymphadenectomy

- D2 + S:

-

D2 lymphadenectomy combined with splenectomy

- D2 + PS:

-

D2 lymphadenectomy combined with distal pancreaticosplenectomy

- NAC:

-

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ASA-PS:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status

- JCGC:

-

Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma

- CD:

-

Clavien–Dindo classification

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

References

Crew KD, Neugut AI (2006) Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 12:354–362

Sano T, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, Nishimoto A, Kurita A, Hiratsuka M, Tsujinaka T, Kinoshita T, Arai K, Yamamura Y, Okajima K (2004) Gastric cancer surgery: morbidity and mortality results from a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing D2 and extended para-aortic lymphadenectomy-Japan clinical oncology group study 9501. J Clin Oncol 22:2767–2773

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2011) Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer 14:113–123

Uyama I, Suda K, Satoh S (2013) Laparoscopic surgery for advanced gastric cancer: current status and future perspectives. J Gastric Cancer 13:19–25

Persiani R, Antonacci V, Biondi A, Rausei S, La Greca A, Zoccali M, Ciccoritti L, D’Ugo D (2008) Determinants of surgical morbidity in gastric cancer treatment. J Am Coll Surg 207:13–19

Aoyagi K, Kouhuji K, Miyagi M, Imaizumi T, Kizaki J, Shirouzu K (2010) Prognosis of metastatic splenic hilum lymph node in patients with gastric cancer after total gastrectomy and splenectomy. World J Hepatol 2:81–86

Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, Bancewicz J, Craven J, Joypaul V, Sydes M, Fayers P (1999) Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial, Surgical Co-operative Group. Br J Cancer 79:1522–1530

Hartgrink HH, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, Bonenkamp JJ, Klein Kranenbang E, Songun I, Welvaart K, van Krieken JH, Meijer S, Plukker JT, van Lanschot JJ, Taat CW, de Graaf PW, von Meyenfeldt MF, Tilanus H, Sasako M (2004) Extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: who may benefit? Final results of the randomized Dutch gastric cancer group trial. J Clin Oncol 22:2069–2077

Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ (2010) Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol 11:439–449

Bamboat ZM, Strong VE (2013) Minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol 107:271–276

Wei HB, Wei B, Qi CL, Chen TF, Huang Y, Zheng ZH, Huang JL, Fang JF (2011) Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 21:383–390

Kawamura Y, Satoh S, Suda K, Ishida Y, Kanaya S, Uyama I (2014) Critical factors that influence the early outcome of laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. doi:10.1007/s10120-014-0392-9June7

Shinohara T, Satoh S, Kanaya S, Ishida Y, Taniguchi K, Isogaki J, Inaba K, Yanaga K, Uyama I (2013) Laparoscopic versus open D2 gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Surg Endosc 27:286–294

Kunisaki C, Makino H, Takagawa R, Kimura J, Ota M, Ichikawa Y, Kosaka T, Akiyama H, Endo I (2015) A systematic review of laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 18:218–226

Uyama I, Sugioka A, Fujita J, Komori Y, Matsui H, Hasumi A (1999) Laparoscopic total gastrectomy with distal pancreatosplenectomy and D2 lymphadenectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2:230–234

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibanes E, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padburt R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M (2009) The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 250:187–196

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240:205–213

Japan Clinical Oncology Group (2013) Postoperative complication criteria according to Clavien–Dindo Classification ver. 2.0. Available at: http://www.jcog.jp/doctor/tool/Clavien_Dindo.html; Accessed 24 June 2015

Suda K, Man-I M, Ishida Y, Kawamura Y, Satoh S, Uyama I (2015) Potential advantages of robotic radical gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma in comparison with conventional laparoscopic approach: a single institutional retrospective comparative cohort study. Surg Endosc 29:673–685

Uyama I, Kanaya S, Ishida Y, Inaba K, Suda K, Satoh S (2012) Novel integrated robotic approach for suprapancreatic D2 nodal dissection for treating gastric cancer: technique and initial experience. World J Surg 36:331–337

Shinohara T, Kanaya S, Taniguchi K, Fujita T, Yanaga K, Uyama I (2009) Laparoscopic total gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Arch Surg 144:1138–1142

Kanaya S, Haruta S, Kawamura Y, Yoshimura F, Inaba K, Hiramatsu Y, Ishida Y, Taniguchi K, Isogaki J, Uyama I (2011) Video: laparoscopy distinctive technique for suprapancreatic lymph node dissection: medial approach for laparoscopic gastric cancer surgery. Surg Endosc 25:3928–3929

Okabe H, Obama K, Tanaka E, Nomura A, Kawamura J, Nagayama S, Itami A, Watanabe G, Kanaya S, Sakai Y (2009) Intracorporeal esophagojejunal anastomosis after laparoscopic total gastrectomy for patients with gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 23:2167–2171

Inaba K, Satoh S, Ishida Y, Taniguchi Y, Isogaki J, Kanaya S, Uyama I (2010) Overlap method: novel intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg 211:e25–e29

Guan G, Jiang W, Chen Z, Liu X, Lu H, Zhang X (2013) Early results of a modified splenic hilar lymphadenectomy in laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy for gastric cancer with stage cT1-2: a case-control study. Surg Endosc 27:1923–1931

Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E (2015) Evaluation of the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic total gastrectomy in clinical stage I gastric cancer patients. World J Surg 39:1782–1788

Nakata K, Nagai E, Ohuchida K, Shimizu S, Tanaka M (2015) Technical feasibility of laparoscopic total gastrectomy with splenectomy for gastric cancer: clinical short-term and long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc 29:1817–1822

Papenfuss WA, Kukar M, Oxenberg J, Attwood K, Nurkin S, Malhotra U, Wilkinson NW (2014) Morbidity and mortality associated with gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 21:3008–3014

da Costa WL Jr., Coimbra FJ, Ribeiro HS, Diniz AL, de Godoy AL, de Farias IC, Begnami MD, Soares FA (2015) Total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an analysis of postoperative and long-term outcomes through time: results of 413 consecutive cases in a single cancer center. Ann Surg Oncol 22:750–757

LaFemina J, Vinuela EF, Schattner MA, Gerdes H, Strong VE (2013) Esophagojejunal reconstruction after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer using a transorally inserted anvil delivery system. Ann Surg Oncol 20:2975–2983

Watanabe M, Miyata H, Gotoh M, Baba H, Kimura W, Tomita N, Nakagoe T, Shimada M, Kitagawa Y, Sugihara K, Mori M (2014) Total gastrectomy risk model: data from 20,011 Japanese patients in a nationwide internet-based database. Ann Surg 260:1034–1039

Filip JE, Mattar SG, Bowers SP, Smith CD (2002) Internal hernia formation after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Am Surg 68:640–643

Miyagaki H, Takiguchi S, Kurokawa Y, Hirao M, Tamura S, Nishida T, Kimura Y, Fujiwara Y, Mori M, Doki Y (2012) Recent trend of internal hernia occurrence after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Surg 36:851–857

Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N, Japanese Laparoscopic Surgery Study Group (2007) A multicenter study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in Japan. Ann Surg 245:68–72

Nagasako Y, Satoh S, Isogaki J, Inaba K, Taniguchi K, Uyama I (2012) Impact of anastomotic complications on outcome after laparoscopic gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Br J Surg 99:849–854

Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, Miyashiro I, Katai H, Kodera Y, Tsujitani S, Seto Y, Furukawa H, Oda I, Ono H, Tanabe S, Kaminishi M (2013) Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer 16:1–27

Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, Kinoshita T, Fujii M, Nashimoto A, Furukawa H, Nakajima T, Ohashi Y, Imamura H, Higashino M, Yamamura Y, Kurita A, Arai K, Acts-Gc Group (2007) Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med 357:1810–1820

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2014) Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines, 4th edn. Kanehara-Shuppan, Tokyo

Sano T, Sasako M, Mizusawa J, Katayama H, Katai H, Yoshikawa T, Yabusaki H, Ito S, Kaji M, Imamura H, Fukushima N, Fujitani K, Iwasaki Y, Kinoshita T (2015) Randomized controlled trial to evaluate splenectomy in total gastrectomy for proximal gastric carcinoma (JCOG0110): final survival analysis. J Clin Oncol 33:103

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Maruzen CO., LTD. (Tokyo, Japan) for their native English speaker’s review of this manuscript.

Funding information

This work was not supported by any grants or funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Masaya Nakauchi, Koichi Suda, Shinichi Kadoya, Kazuki Inaba, Yoshinori Ishida, and Ichiro Uyama have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakauchi, M., Suda, K., Kadoya, S. et al. Technical aspects and short- and long-term outcomes of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a single-institution retrospective study. Surg Endosc 30, 4632–4639 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4726-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4726-4