Abstract

Background

The incidence of internal hernia after gastrectomy can increase with the increasing use of laparoscopic surgery, although this trend has not been elucidated.

Methods

Clinical information was collected from medical records and by questionnaire for 18 patients who underwent surgical treatment for internal hernia after gastrectomy for gastric cancer in 24 hospitals from January 2005 to December 2009.

Results

Gastrectomy for gastric cancer was open/distal gastrectomy (DG) in five (28%) patients, open/total gastrectomy (TG) in seven (39%), laparoscopy-assisted/DG in three (17%), and laparoscopy-assisted/TG in 3 (17%). Reconstruction was by Roux-Y methods in all patients. The hernia orifice was classified as a jejunojejunostomy mesenteric defect in eight patients (44%), dorsum of the Roux limb (Petersen’s space) in eight (44%), and one (5%) each of esophageal hiatus and mesenterium of the transverse colon. Among 8,983 patients who underwent gastrectomy for gastric cancer, a postoperative survey revealed that 13 patients underwent surgical treatment for internal hernia in the same hospitals. The 3-year incidence rate of the internal hernia was 0.19%, which was significantly higher after laparoscopy-assisted than open gastrectomy (0.53 vs. 0.15%, p = 0.03). Patients with an internal hernia had a mean (±SD) low weight at hernia operation (body mass index 17.9 ± 1.6 kg/m2) and marked weight loss after gastrectomy (weight reduction 15.6 ± 5.8%).

Conclusions

Gastrectomy with Roux-Y reconstruction for gastric cancer leaves several spaces that can cause internal hernia formation. Laparoscopic surgery and postoperative body weight loss are potential risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intraabdominal adhesions are the most common cause of postoperative bowel obstruction after abdominal surgery, accounting for ~62–75% of cases [1–3]. These adhesions increase the risk of various subsequent complications, such as massive bowel infarction and pulmonary disease [3, 4]. Therefore, various contrivances, such as the use of antiadhesive material [5, 6], are employed to protect against the development of postoperative adhesions. Laparoscopic surgery is the most effective method that can reduce postoperative intraabdominal adhesions, and the incidence of bowel obstruction after laparoscopic surgery has decreased markedly relative to that with open surgery [7–10].

Another complication that has attracted attention in recent years is the postoperative internal hernia, representing bowel obstruction often irrelevant to intraabdominal adhesions [11, 12]. Postoperative internal hernia is an acute or chronic protrusion of a viscus through an iatrogenic mesenteric or peritoneal aperture [13]. With respect to gastrectomy, internal hernia often occurs after specific reconstruction procedures, such as Roux-Y [14] and Billroth II [15] reconstruction, probably because of the multiplicity and large size of the iatrogenically created artificial apertures compared with the less frequent incidence after other reconstruction procedures (e.g., Billroth I reconstruction, esophagogastrostomy after proximal gastrectomy).

Studies of complications after gastric Roux-Y bypass surgery for obesity have reported a a significantly higher incidence of internal hernia after laparoscopic surgery than open surgery [11], suggesting that a reduction of intraabdominal adhesion in fact increases the risk, contrary to adhesive bowel obstruction. For patients who undergo gastrectomy for gastric cancer, which often includes a similar reconstruction procedure, the incidence of internal hernia may be more frequent after laparoscopic surgery than after open surgery as reported after bariatric surgery [11]. It is thought that the development of internal hernia after gastrectomy for gastric cancer is rare compared to that with gastric bypass surgery. In today’s era of laparoscopic surgery, we should pay more attention to postoperative internal hernia, but to our knowledge there are only a few reports on the incidence of internal hernia after gastrectomy. The present retrospective multicenter study was designed to determine the true status of internal hernia after gastrectomy, including its developmental pattern, incidence, treatment, and outcome.

Methods

Patients

The study included analysis of questionnaires and medical and surgical records of 18 patients who underwent surgical treatment for internal hernia after gastrectomy between January 2005 and December 2009 in 24 high-volume centers (>40 gastrectomies per year) in the Kinki area, Japan. Based on the operative records, cases of intestinal herniation through adhesive bands that were treated by synechiotomy were excluded. Among the 18 patients, 13 underwent surgery for internal hernia in the same hospital where their gastrectomy was performed; the remaining five patients underwent gastrectomy in the same hospitals beyond the study period or in hospitals other than the 24 participating centers. None of the 18 patients developed cancer recurrence at or after surgical treatment of the internal hernia.

During the study period, 8,983 patients underwent curative gastrectomy in the participating 24 centers and adequate postoperative follow-up every 3 months until December 2010. Also, the medical charts indicated that none underwent surgical treatment for internal hernia in other hospitals. The mean follow-up period after gastrectomy in these patients was 30.3 months. Patients with pathologic stage II or higher diagnosed after 2007 generally received postoperative chemotherapy using S-1 (tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil potassium).

These 8,983 patients consisted of 7,721 who underwent open gastrectomy and 1,262 in whom laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy (LAG) was performed. The former group was subdivided into 4,756 with open/distal gastrectomy (OPDG), 2,748 with open/total gastrectomy (OPTG), and 217 with open/proximal gastrectomy (OPPG). Of the LAG group, 1,028 patients underwent LA distal gastrectomy (LADG), 218 LA total gastrectomy (LATG), and 16 LA proximal gastrectomy (LAPG).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. The incidence and 3-year cumulative incidence rates were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method. Correlations between incidences of surgical procedures were evaluated by the log-rank test. All analyses were carried out using JMP software version 8.0.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, SA) for Windows. A p value <0.05 denoted the presence of statistical significance.

Results

Clinical profile of internal hernia after gastrectomy

Eighteen patients underwent surgical treatment of internal hernia after gastrectomy for gastric cancer (Table 1). They included 4 women and 14 men, aged 51–81 years (median 72 years). The median interval between preceding gastrectomy and surgery for internal hernia was 411 days (range 3–3437 days). The mean body mass index (BMI) at time of surgery for the hernia was 17.9 ± 1.6 kg/m2, and the mean body weight reduction after gastrectomy was 15.6 ± 5.8%: 16.5 kg/m2 and 17.6%, respectively, for the 10 patients of the total gastrectomy group and 19.3 kg/m2 and 13.5% for the eight patients of the distal gastrectomy group. The operative procedures for preceding gastrectomy were OPDG in five (27%) patients, OPTG in seven (39%), LADG in three (17%), and LATG in three (17%). Reconstruction was by the Roux-Y method with antecolic route in nine patients and the retrocolic route in nine patients. Details of the preceding gastrectomy were available for 14 patients and showed the use of antiadhesion material in five patients and closure or fixation of both of the mesenterium of the transverse colon and jejunojejunostomy mesenteric defect in 10 patients. Petersen’s space was not closed in any of the patients.

The most common presentation of internal hernia was abdominal pain (n = 16, 89%) followed by nausea/vomiting (n = 6, 33%). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) was conducted in all cases, and there was a preoperative diagnosis of internal hernia in 14 cases (78%), as shown in Fig. 1. Emergency operation was required in four cases (22%). With regard to the approach used for surgery of the internal hernia, a laparoscopic procedure was adopted for two patients (11%) who had undergone the preceding gastrectomy via a laparoscopic approach, whereas the open procedure was applied in the remaining 16 patients. Figure 2 indicates the various hernia orifices in these patients, including jejunojejunostomy mesenteric defect in eight patients (44%), dorsum of the Roux limb (Petersen’s space) in eight (44%), and one (6%) each of esophageal hiatus and mesenterium of the transverse colon. Because of bowel necrosis, bowel resection was performed in three (17%) patients. The operating time was 270 ± 53 min, with intraoperative blood loss of 283 ± 126 ml (Table 2). With regard to the postoperative course, one (6%) patient developed sepsis with disseminated intravascular coagulation but recovered later and was discharged from the hospital without other complications. Another patient (6%), who underwent a 360-cm small bowel resection, developed short-bowel syndrome. There were no deaths in this series.

Analysis of frequency and cumulative incidence of internal hernia

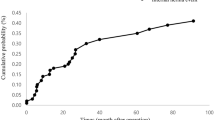

The frequency and incidence of internal hernia were calculated, excluding five patients who had undergone preceding gastrectomy beyond the dates of the study period and/or the surgery was conducted in a hospital other than the 24 participating centers. The frequency of internal hernia was calculated according to each gastrectomy surgical procedure among 8,983 curative gastrectomies conducted during this period. The overall frequency of the internal hernia was 0.14% but was not observed after open and laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy (Table 3). The median latency between gastrectomy and the diagnosis of internal hernia was 12.0 months. A trend was noted of a gradual increase in laparoscopic surgery (data not shown). The cumulative incidence rate of internal hernia was calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method (Fig. 3). The 3-year incidence was 0.19% for all patients, which was significantly higher for LAG than in open gastrectomy (0.53 vs. 0.15%, p = 0.03) (Fig. 3a). In particular, the rate for LATG was highest among all other procedures (Fig. 3b).

Cumulative incidence of internal hernia after gastrectomy according to the gastrectomy procedure for gastric cancer. A total of 8983 patients underwent gastrectomy between January 2005 and December 2009 in 24 hospitals. Among these patients, 13 underwent surgical treatment for internal hernia. a The 3-year cumulative incidence rate of internal hernia after laparoscopic gastrectomy (n = 4) was 0.53%, which was significantly higher than that after open gastrectomy (n = 9) (p = 0.03). b The 3-year cumulative incidence of internal hernia according to the gastrectomy procedure. The cumulative rate was the highest after laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) (1.22%, p < 0.05). OPDG open/distal gastrectomy, OPTG open/total gastrectomy, LADG laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy

Discussion

This is the first multiinstitutional cohort study of the incidence of internal hernia after gastrectomy performed for gastric cancer. The results showed a 3-year incidence of 0.19%, indicating that internal hernia is not a negligible postoperative complication.

The most considerable reason for this trend is the increased use of laparoscopic surgery. The decreased intraabdominal adhesions after laparoscopic surgery, which provides overall benefits associated with fewer various postoperative complaints and complications [7, 8], is widely regarded to be the major risk factor for the development of an internal hernia. For example, Capella et al. [11], who conducted a retrospective study of bariatric surgery, reported that the incidence of internal hernia following the Roux-Y gastric bypass was significantly higher after laparoscopic surgery than after open surgery (9.7 vs. 0%). In our study, although it included various surgical procedures, the cumulative incidence was also significantly higher after laparoscopic gastrectomy than after open gastrectomy (0.53 vs. 0.15%, p = 0.03). In Japan, the rate of LAG for gastric cancer has increased annually from 6.3% in 2000 to 25.7% in 2009 [16]. This rate could have a future impact on the incidence of internal hernia.

Another notable observation was that an internal hernia was observed only in patients with the Roux-Y reconstruction. Roux-Y reconstruction is the most popular procedure for total gastrectomy, being employed in more than 90% of the surgical procedures in Japan [17]. However, for distal gastrectomy, Billroth I and II and Roux-Y has been widely and preferentially used in many countries. Although there is no solid evidence based on randomized clinical trials, Billroth I, which allows physiological food passage through the duodenum, is popular in Japan [17], whereas the Roux-Y reconstruction is still used infrequently in Japan [17]. Therefore, the incidence of internal hernia after gastrectomy with Roux-Y reconstruction was considered to be much higher than our observation. Moreover, use of the reconstruction has been gradually increasing in recent years [17], most likely to avoid anastomotic leakage and reflux inflammation of the remnant stomach [18, 19]. In our study, the incidence of internal hernia tended to be higher after total gastrectomy than distal gastrectomy (3-year incidence rates: 0.29 vs. 0.15%, p = 0.358). Although information on the reconstruction procedure for all registered cases was not available, except for those with internal hernia, this difference may be attributed in part to the difference in the frequency of Roux-Y reconstruction. Therefore, internal hernias may increase in the future in parallel with the change in the reconstruction method used.

The high risk of internal hernia after Roux-Y reconstruction is probably related to the abdominal spaces specifically created after Roux-Y reconstruction, with each space becoming a potential orifice for an internal hernia. Therefore, treatment of these artificial spaces is an important surgical issue to be discussed. The greatest factor possibly affecting the incidence of internal hernia after gastrectomy is closure of the mesenteric defects. Intuitively, an obliterated mesenteric defect should prevent the incidence of internal hernias, and several groups have recommended routine closure of all mesenteric defects, citing a decrease in the incidence of internal hernias after gastric bypass [20–25]. In our experience, jejunojejunostomy-associated mesenteric defects were surgically closed in six of eight patients with a jejunojejunostomy-repaired mesenteric hernia. Therefore, firmer closure with nonabsorbable surgical suture might be required. In general, we do not surgically close Petersen’s spaces during gastrectomy. When the orifice is not closed, it is considered better to leave it large [25]. A large orifice may allow transposition of unfixed small intestine but rarely causes obstruction or strangulation, which clinically presents as an internal hernia. Management of the orifices during gastrectomy is still controversial, and further investigation should be carried out to identify the most effective procedure.

Body weight loss seems a risk factor for patients with a postgastrectomy internal hernia. In our study, the mean reduction in BMI in patients who developed an internal hernia after total gastrectomy was 17.6%, which was a larger loss than that reported in other studies (range 6.6–10.8%) [26, 27]. Similarly, the reduction (13.5%) after distal gastrectomy in our study was larger than in other studies (range 9.1–10.5%) [28, 29]. Weight loss, even when intentional after bariatric surgery, is considered a risk factor for internal hernia [21, 30]. The large decrease in mesenteric fat postoperatively constitutes a major part of the weight loss after surgery [31, 32]. Therefore, a large weight loss could increase the size of the mesenteric defect, thus enhancing the development of internal hernia [33].

The rare incidence and the associated nonspecific presentation make it difficult to diagnose an internal hernia preoperatively. However, CT can be helpful in depicting signs of internal herniation [34, 35]. The swirled appearance of mesenteric fat or vessels was found to be the best single predictor of hernia, with a sensitivity of ~80% and specificity of 90% [36]. In the present study, a preoperative diagnosis was achieved in 14 cases (78%) via abdominal CT scans. CT resolution has markedly improved, and 3D images can be constructed easily (Fig. 1b) with improved diagnostic power [37–40].

Conclusions

Roux-Y reconstruction creates several intraabdominal spaces that can promote internal herniation. The 3-year incidence rate of internal hernia after gastrectomy performed for gastric cancer was 0.19%. Laparoscopic surgery and body weight loss may be risk factors for internal herniation. With the increase in popularity of LAG, attention must be focused on preventing morbidity associated with internal hernia formation.

References

Ellis H, Moran BJ, Thompson JN et al (1999) Adhesion-related hospital readmissions after abdominal and pelvic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 353:1476–1480

Menzies D, Ellis H (1990) Intestinal obstruction from adhesions: how big is the problem? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 72:60–63

Fevang BT, Fevang J, Stangeland L et al (2000) Complications and death after surgical treatment of small bowel obstruction: a 35-year institutional experience. Ann Surg 231:529–537

Sosa J, Gardner B (1993) Management of patients diagnosed as acute intestinal obstruction secondary to adhesions. Am Surg 59:125–128

Fazio VW, Cohen Z, Fleshman JW et al (2006) Reduction in adhesive small-bowel obstruction by Seprafilm adhesion barrier after intestinal resection. Dis Colon Rectum 49:1–11

Mohri Y, Uchida K, Araki T et al (2005) Hyaluronic acid-carboxycellulose membrane (Seprafilm) reduces early postoperative small bowel obstruction in gastrointestinal surgery. Am Surg 71:861–863

Gervaz P, Inan I, Perneger T et al (2010) A prospective, randomized, single-blind comparison of laparoscopic versus open sigmoid colectomy for diverticulitis. Ann Surg 252:3–8

Sharma B, Baxter N, Grantcharov T (2010) Outcomes after laparoscopic techniques in major gastrointestinal surgery. Curr Opin Crit Care 16:371–376

Rosin D, Zmora O, Hoffman A et al (2007) Low incidence of adhesion-related bowel obstruction after laparoscopic colorectal surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 17:604–607

Dowson HM, Bong JJ, Lovell DP et al (2008) Reduced adhesion formation following laparoscopic versus open colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 95:909–914

Capella RF, Iannace VA, Capella JF (2006) Bowel obstruction after open and laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. J Am Coll Surg 203:328–335

Hosono S, Ohtani H, Arimoto Y et al (2007) Internal hernia with strangulation through a mesenteric defect after laparoscopy-assisted transverse colectomy: report of a case. Surg Today 37:330–334

Ghahremani GG (1984) Internal abdominal hernias. Surg Clin N Am 64:393–406

Aoki M, Saka M, Morita S et al (2010) Afferent loop obstruction after distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction. World J Surg 34:2389–2392

Gayer G, Barsuk D, Hertz M et al (2002) CT diagnosis of afferent loop syndrome. Clin Radiol 57:835–839

Education Committee of Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery (2010) 10th Nationwide survey of endoscopic surgery in Japan. J Jpn Soc Endosc Surg J 15:567–577

Morita S, Sano T, Tanaka N et al (2010) Trends in reconstruction and anastomosis for patients with gastric cancer. Jpn J Cancer Clin 56:9–14

Csendes A, Burgos AM, Smok G et al (2009) Latest results (12–21 years) of a prospective randomized study comparing Billroth II and Roux-en-Y anastomosis after a partial gastrectomy plus vagotomy in patients with duodenal ulcers. Ann Surg 249:189–194

Kojima K, Yamada H, Inokuchi M et al (2008) A comparison of Roux-en-Y and Billroth-I reconstruction after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg 247:962–967

Iannelli A, Facchiano E, Gugenheim J (2006) Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg 16:1265–1271

Comeau E, Gagner M, Inabnet WB et al (2005) Symptomatic internal hernias after laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc 19:34–39

Coleman MH, Awad ZT, Pomp A et al (2006) Laparoscopic closure of the Petersen mesenteric defect. Obes Surg 16:770–772

Bauman RW, Pirrello JR (2009) Internal hernia at Petersen’s space after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 6.2% incidence without closure—a single surgeon series of 1047 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 5:565–570

Miyashiro LA, Fuller WD, Ali MR (2010) Favorable internal hernia rate achieved using retrocolic, retrogastric alimentary limb in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 6:158–162

Steele KE, Prokopowicz GP, Magnuson T et al (2008) Laparoscopic antecolic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with closure of internal defects leads to fewer internal hernias than the retrocolic approach. Surg Endosc 22:2056–2061

Davies J, Johnston D, Sue-Ling H et al (1998) Total or subtotal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma? A study of quality of life. World J Surg 22:1048–1055

Tyrvainen T, Sand J, Sintonen H et al (2008) Quality of life in the long-term survivors after total gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 97:121–124

Nunobe S, Okaro A, Sasako M et al (2007) Billroth 1 versus Roux-en-Y reconstructions: a quality-of-life survey at 5 years. Int J Clin Oncol 12:433–439

Takiguchi S, Yamamoto K, Hirao M et al. (2011) A comparison of postoperative quality of life and dysfunction after Billroth I and Roux-en-Y reconstruction following distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: results from a multi-institutional RCT. Gastric Cancer. doi:10.1007/s10120-011-0098-1

Muller MK, Rader S, Wildi S et al (2008) Long-term follow-up of proximal versus distal laparoscopic gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Br J Surg 95:1375–1379

Hope WW, Sing RF, Chen AY et al (2010) Failure of mesenteric defect closure after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. JSLS 14:213–216

Miyato H, Kitayama J, Hidemura A et al (2010) Vagus nerve preservation selectively restores visceral fat volume in patients with early gastric cancer who underwent gastrectomy. J Surg Res. doi:10.1002/bjs.6453

Papasavas PK, Caushaj PF, McCormick JT et al (2003) Laparoscopic management of complications following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Surg Endosc 17:610–614

Mathieu D, Luciani A (2004) Internal abdominal herniations. Am J Roentgenol 183:397–404

Takeyama N, Gokan T, Ohgiya Y et al (2005) CT of internal hernias. Radiographics 25:997–1015

Lockhart ME, Tessler FN, Canon CL et al (2007) Internal hernia after gastric bypass: sensitivity and specificity of seven CT signs with surgical correlation and controls. Am J Roentgenol 188:745–750

Krajewski S, Brown J, Phang PT et al (2011) Impact of computed tomography of the abdomen on clinical outcomes in patients with acute right lower quadrant pain: a meta-analysis. Can J Surg 54:43–53

Kothari SN (2011) Bariatric surgery and postoperative imaging. Surg Clin N Am 91:155–172

Hong SS, Kim AY, Kwon SB et al (2010) Three-dimensional CT enterography using oral Gastrografin in patients with small bowel obstruction: comparison with axial CT images or fluoroscopic findings. Abdom Imaging 35:556–562

Kawkabani Marchini A, Denys A, Paroz A et al (2011) The four different types of internal hernia occurring after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass performed for morbid obesity: are there any multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) features permitting their distinction? Obes Surg 21:506–516

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted without any financial support. The authors thank all participants of the Osaka University Clinical Research Group for Gastroenterological Surgery. The following is a list of the 24 high-volume centers in Kinki area that participated in this study: National Hospital Organization Osaka National Hospital, Osaka; Toyonaka Municipal Hospital, Osaka; Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases, Osaka; Kansai Rosai Hospital, Hyogo; Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka; Osaka University Hospital, Osaka; Osaka General Medical Center, Osaka; Osaka Rosai Hospital, Osaka; Osaka Koseinenkin Hospital, Osaka; Nara Hospital Kinki University Faculty of Medicine, Nara; NTT West Osaka Hospital, Osaka; Higashiosaka City General Hospital, Osaka; Hyogo Prefectural Nishinomiya Hospital, Hyogo; Ikeda City Hospital, Osaka; Otemae Hospital, Osaka; Itami City Hospital, Hyogo; Bell Land General Hospital, Osaka; Moriguchi Keijinkai Hospital, Osaka; Social Insurance Kinan Hospital, Wakayama; Yao Municipal Hospital, Osaka; Kinki Central Hospital, Hyogo; Suita Municipal Hospital, Osaka; Minoh City Hospital, Osaka; Saiseikai Senri Hospital, Osaka, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miyagaki, H., Takiguchi, S., Kurokawa, Y. et al. Recent Trend of Internal Hernia Occurrence After Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. World J Surg 36, 851–857 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-012-1479-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-012-1479-2