Abstract

Background

Primary immunodeficiency disorders (PID) are a group of heterogeneous disorders mainly characterized by severe and recurrent infections and increased susceptibility to malignancies, lymphoproliferative and autoimmune conditions. National registries of PID disorders provide epidemiological data and increase the awareness of medical personnel as well as health care providers.

Methods

This study presents the demographic data and clinical manifestations of Iranian PID patients who were diagnosed from March 2006 till the March of 2013 and were registered in Iranian PID Registry (IPIDR) after its second report of 2006.

Results

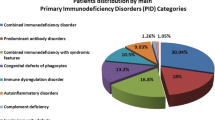

A total number of 731 new PID patients (455 male and 276 female) from 14 medical centers were enrolled in the current study. Predominantly antibody deficiencies were the most common subcategory of PID (32.3 %) and were followed by combined immunodeficiencies (22.3 %), congenital defects of phagocyte number, function, or both (17.4 %), well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency (17.2 %), autoinflammatory disorders (5.2 %), diseases of immune dysregulation (2.6 %), defects in innate immunity (1.6 %), and complement deficiencies (1.4 %). Severe combined immunodeficiency was the most common disorder (21.1 %). Other prevalent disorders were common variable immunodeficiency (14.9 %), hyper IgE syndrome (7.7 %), and selective IgA deficiency (7.5 %).

Conclusions

Registration of Iranian PID patients increased the awareness of medical community of Iran and developed diagnostic and therapeutic techniques across more parts of the country. Further efforts must be taken by increasing the coverage of IPIDR via electronically registration and gradual referral system in order to provide better estimation of PID in Iran and reduce the number of undiagnosed cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Primary immunodeficiency disorders (PID) are a heterogeneous group of hereditary defects in the development or the function of immune system [1–4]. PID patients are more likely to experience recurrent and/or severe infections and have a tendency to immunologic complications [5–8]. Since the identification of the first PID in 1952, more than 220 types of these disorders have been described in the literature [9, 10]. The increasing number of known types of PID in the past two decades is mainly due to the increasing knowledge regarding the function of immune system in addition to more accurate molecular and genetic diagnostic methods [11, 12]. Lack of awareness on PIDs in physicians, is the major reason in delayed diagnosis and inadequate treatment resulting in morbidity and mortality [13–15].

PID has been generally considered as rare disorders worldwide [12]. However, according to epidemiologic studies, the true incidence and prevalence of PID are enormously underestimated due to the lack of effective and available screening tests and it may affect around six million individuals at its upper estimation [12]. Registry reports of several countries show wide variations in geographical and racial prevalence as well as the frequency of different types of PID [12, 16]. Moreover, these data provide epidemiological information as well as increasing the awareness of physicians and health care system strategists [11].

Iranian Primary Immunodeficiency Registry (IPIDR) was established in August 1999 with the main aim of determining the prevalence of various types of PID in Iran [11]. The first registry report of Iran was published in 2002 consisted of 440 PID patients with primary antibody deficiencies as the most common group of these disorders [17]. The second report was published in 2006 included 930 patients (490 new cases) with similarities in the prevalence of different groups of PID in the first report [11]. This study presents the demographic and clinical presentation of Iranian PID patients who were diagnosed and registered in IPIDR from 14 participant medical centers between March 2006 and March 2013.

Patients and Methods

Iranian Primary Immunodeficiency Registry (IPIDR)

The main aim of IPIDR was to provide epidemiological data of PID in Iran. By the March of 2006, 930 PID patients from different provinces of the country were registered in IPIDR during a 30 years period of time and 731 new patients were registered from March 2006 till March 2013.

By the last estimation in 2011, Iran has a population of 75,669,750 registered Iranian citizens and an additional 1.959,000 citizens of other countries mainly refugees from its neighbor countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq. In addition to Iranian citizens, all PID cases who were a resident of Iran at the time of birth and diagnosis were also registered in IPIDR. The process of this study as well as data entry, analysis and reporting of IPIDR was approved by Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Science. Moreover, all patients who entered this registry, or their parents or legal guardians, if need, were asked to fill an informed consent guaranteeing patients’ names and personal data won’t be published under any circumstances.

Patients’ Enrollment

The diagnosis of PID patients was made according to the criteria of Pan-American Group for Immunodeficiency (PAGID), European society for immunodeficiencies (ESID) and the International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS), between March 2006 and March 2013[18]. Secondary defects of immune system such as HIV infection were ruled out by the use of standard tests in all cases. Laboratory evaluations were performed in the study group as indicated including immunoglobulin serum levels, IgG subtypes serum level, isohemagglutinin tests, assessment of post-vaccination serum antibody response such as anti-tetanus, anti-diphtheria and anti-pneumococcal, flow cytometry evaluation of lymphocyte subtypes, chemotaxis studies, nitro blue tetrazolium dye test, granulocyte function tests, complement component and hemolytic titration of complement (C3, C4, CH50), and DNA mutation analysis for diagnosis confirmation [11].

Participant Centers

Registry database is located in Children’s Medical Center (Tehran, Iran) which serves as a referral hospital for suspected or diagnosed cases of PID. In addition, 14 medical centers affiliated to 13 medical science universities collaborated in the registry program from 13 major states of the country including Tehran, Azerbaijan, Khorasan, Isfahan, Fars, Gilan, Mazandaran, Khuzestan, Yazd, Golestan, Qazvin, Ardabil and Sistan and Baluchestan (Fig. 1). All of the participated centers had access to mandatory laboratory equipments for immunological evaluation of patients according to the standard diagnostic approaches. It should be mentioned that cases with suspected diagnosis were referred and re-evaluated in Children’s Medical Center for definitive diagnosis.

Data Collection

All data were provided by the same immunologists who were at the charge of patients’ diagnosis and clinical care. Participant medical centers have been given the choice to register their patients by either the online access or the old paper and pencil method. In the online method, every participant immunologist has been given a user name and password at the registry website by using the following address: http://rcid.tums.ac.ir/. Participants could use their limited access for entering the diagnosis and demographic data of their patients. After reviewing the cases by the administrator of the system for duplicated or old cases, participants were able to enter the family history, clinical features, laboratory data, and paraclinical findings of the patients as well as the follow-up information of their patients.

In the second method, the following steps were made: Participants were asked to fill a one-page preliminary questionnaire including the diagnosis and the demographic data for each patient. After the primary review by secretary for elimination of duplicated or old cases, another four-page questionnaire was sent and the centers were asked to complete clinical features, laboratory data, and paraclinical findings of their patients as well as the follow-up information. After recheck for probable mistakes, all reported cases provided by the both methods were reviewed by the head of the registry program and then included in the database if they met the standard diagnostic criteria.

Database

All data, both sent by online method or paper questionnaire, were finally gathered at our online database with the ability to convert all desired parameters to Microsoft Excel 2010 data files (Microsoft, USA). All information were converted and saved in Excel data files after any change in the online database to prevent unexpected data loss. Participated physicians were able to access the full information of their own patients but were not allowed to see the data sent by other physicians or make any change in their own cases before the approval of system’s administrator. Online database was updated frequently and all follow-up data sent by the end of the study period were included. For ethical considerations, patients’ names in database were replaced with codes before analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data were collected in Excel database and were converted for analysis using the SPSS statistical software package version 19.0 (IBM corporation, USA). Linear regression analysis was performed to evaluate the chronological effect of time on the different parameters. A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ Characteristics and Distribution of PID

A total number of 731 PID patients (455 male and 276 female) from 14 medical centers were enrolled in the study in the time period between March 2006 and March 2013. Thirty-six types of diagnoses were made in the population study which was included into 8 groups of PID disorders according to the IUIS classification. Predominantly antibody deficiencies were the most common group of PID affecting 236 patients (32.3 %) and were followed by combined immunodeficiencies in 163 cases (22.3 %), congenital defects of phagocyte number, function, or both in 127 cases (17.4 %), well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency in 126 cases (17.2 %), autoinflammatory disorders in 38 cases (5.2 %), diseases of immune dysregulation in 19 cases (2.6 %), defects in innate immunity in 12 cases (1.6 %), and complement deficiencies in 10 cases (1.4 %). Figure 2 shows the share of each PID groups.

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) was the most common specific disorder consisting of 154 cases (21.1 %). Other prevalent disorders were common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) in 109 cases (14.9 %), hyper IgE syndrome (HIgE) in 56 cases (7.7 %), selective IgA deficiency in 55 cases (7.5 %), ataxia-telangiectasia (AT) in 52 cases (7.1 %), chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) in 51 cases (7 %), Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) in 37 cases (5.1 %), X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) in 33 cases (4.5 %), severe congenital neutropenia in 31 cases (4.2 %), leukocyte adhesion deficiency (LAD) in 29 cases (4 %), hyper IgM syndrome (HIgM) in 28 cases (3.8 %), Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome in 16 cases (2.2 %), Mendelian susceptibility of mycobacterial disease (MSMD) and hereditary angioedema each in 10 cases (1.4 %). The prevalence of other disorders consisting of less than 10 patients is summarized in Table I.

Geographical Distribution

Of 731 PID patients, 724 (99 %) had Iranian citizenship while 5 cases (0.7 %) had Iraqi citizenship, 1 case (0.1 %) had Tajik citizenship and another one (0.1 %) had Afghan citizenship, while all were the inhabitants of Iran. The approximate number of diagnosed cases of PID in each year was 104 without any significant difference during the past 7 years. The cumulative incidence of PID is about 9.7 per 1,000,000 populations during the last 7 years, with a regional variation from 1 to 22.4 per 1,000,000 populations. Of 731 cases, 327 (44.7 %) were living in Tehran province mainly in Tehran, the capital of the country. About 19 % of the country’s population lives in this province. Other provinces with high number of registered PID patients were north provinces including Azerbaijan in north west (16.1 %), Isfahan in center (7.5 %), and Khorasan in north east (7 %). There was significantly lower number of registered cases in west and south east provinces which was accompanied with a lack of participant medical centers in these provinces (Fig. 1). The number and the cumulative incidence of PID in various provinces of the country during the past 7 years are summarized in Table II.

Age Distribution and Diagnostic Delay

The median age of the patients at the end of the study was 8 years ranged from 2 months to 56 years. The median age of the patients at the onset of disease was 1 year ranged from shortly after birth to 40 years. One hundred and nineteen out of 731 cases (16.3 %) experienced the first symptom before the age of 1 month and 406 cases (55.5 %) showed the first symptom by the age of 1 year. Only 30 out of 731 cases (4.1 %) showed the first manifestation of disease after 14 years of age. This included, most notably, 8 patients with hereditary angioedema (80 % of cases), 12 patients with CVID (11 % of cases), and 5 patients with hyper-IgE syndrome (9 % of cases). The median age of the patients at the time of diagnosis was 3 years and 6 months ranged from 1 month to 51 years. The median diagnostic delay was 1 year ranged from 0 to 28 years. The highest diagnostic delay was observed in a CVID patient who suffered from diarrhea from 28 years prior to the diagnosis. Of 731 cases, diagnosis was made in 380 (52 %) within 1 year from the onset of disease and within 2 years from the onset of disease in 475 cases (65 %). Diagnostic delay was higher than 5 years only in 129 cases (17.6 %). Highest diagnostic delay was observed among patients with MHC II deficiency (median, 6.04 years), followed by NEMO deficiency (median, 6 years), Dock8 deficiency (median, 5 years), and CVID (median, 4 years). Patients’ demographic data are summarized in Table I. There was a direct association between the age of the patients at the onset of disease and diagnostic delay (r = 0.012, F = 4.767, P = 0.03). The same kind of association was observed between the current age of patients and diagnostic delay (r = 0.289, F = 154.707, P < 0.001). Figure 3 shows diagnostic delay in population study based on the age of the patients at the onset of disease and the current age of patients respectively.

Family History and Consanguinity

A family history of PID was found in 126 cases (17.2 %). Family history of recurrent infections without a known diagnosis of PID was positive in 86 cases (11.7 %). In 191 cases (26.1 %), a positive family history of death at an early age was documented. A history of diagnosed cancer was reported in the family of 36 patients (4.9 %); and 46 individuals (6.2 %) revealed a positive family history for autoimmune disorders.

Consanguineous marriage was observed in the parents of 461 cases (63.1 %). There was a significant difference between the consanguinity rates of various types of PID. Parental consanguinity was most common in diseases of immune dysregulation and combined immunodeficiencies and was observed in 100 % (19 out of 19 cases) and 71.2 % (116 out of 163 cases) of cases with these groups of PID respectively. In contrast, patients with complement deficiencies and autoinflammatory disorders had the lowest consanguinity rate with 40 % (4 out of 10 cases) and 39.5 % (15 out of 38 cases) respectively. Table I shows consanguinity rate among various groups and types of PID.

First Presentation

The most common first presentation of PID patients was pneumonia observed in 171 cases (23.4 %). It was followed by eczema and itching in 54 cases (7.4 %), diarrhea in 52 cases (7.1 %), ataxic gait in 50 cases (6.8 %), omphalitis and/or delayed umbilical cord detachment in 50 cases (6.8 %), otitis media in 46 cases (6.3 %), recurrent sinusitis in 35 cases (4.8 %), other upper respiratory tract infections in 39 cases (5.3 %), episodic fever and abdominal pain in 37 (5.1 %), superficial abscesses in 35 cases (4.8 %), lymphadenopathy in 15 cases (2.1 %), mucocutaneous candidiasis in 25 cases (3.4 %), BCGosis in 17 cases (2.3 %), swelling in various parts of skin in 10 cases (1.4 %), other cutaneous manifestations in 37 (5 %), failure to thrive in 7 cases (1 %). Other presenting features which were observed in less than 5 cases including fever of unknown origin, oral lesions, bacterial and viral meningitis, cellulitis, conjunctivitis, deep organ abscesses, alopecia, easy bruising, gingivitis, arthralgia and septic arthritis. Regarding the observation of rare PID complications as the presenting feature, PID was first presented in one patient affected by XLA with Kawasaki disease. In addition, Hodgkin’s lymphoma was the presenting manifestation in one patient with AT.

Early Outcome

From 731 patients, 137 cases (18.7 %) were confirmed to be dead (86 male and 51 female). Out of 731 cases, 114 (15.6 %) could not be located during the last 6 months of the study period. Beside the specific disorders with a frequency of less than 10 cases, mortality rate was highest in combined immunodeficiencies (115 SCID cases and 1 CD40 deficiency case) with a mortality rate of 71.1 % (136 out of 163 cases) and lost to follow up rate of 8.6 % (14 out of 163 cases). Four patients (1.7 %) with predominantly antibody deficiencies (3 CVID cases and 1 case of HIgM) and 8 patients (6.3 %) with defects of phagocyte number, function, or both (4 cases of LAD, 1 case of CGD, 1 case of severe congenital neutropenia, 1 Dock8 deficiency case, and 1 case of cyclic neutropenia,), 8 cases (6.3 %) with well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency (3 cases of AT, 3 cases of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, 1 case of hyper-IgE syndrome, and 1 case of Nijmegen syndrome), and 2 patients (13.3 %) with diseases of immune dysregulation (1 case of Chediak-Higashi syndrome, and 1 case of XLP) were also dead by the end of the follow-up period. Cardiopulmonary failure due to severe pneumonia and sepsis was the cause of death in all cases except of 1 case of SCID who died from intracranial hemorrhage, another 1 case of SCID who died of end stage renal disease, and 1 case of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome died of severe internal hemorrhage.

Total Number of Registered Iranian PID Patients

By the March of 2013, a total number of 1,661 PID patients (1,028 male and 633 female) were registered in IPIDR. This number includes 930 PID patients who were diagnosed during a 30 years period of time till the March of 2006 and 731 PID cases were diagnosed and registered in IPIDR afterwards (Table III). The cumulative incidence of PID in Iran during the past 10 years is estimated to be around 13 cases per 1,000,000 populations. The approximate number of diagnosed PID cases was reported to be 7 per year in 1980s, 30 per year 1990s, 58 per year from 2000 to the March of 2006, and 104 per year afterwards till the March of 2013. Figure 4 shows the number of registered PID patients during various time periods. Out of these 1,661 PID patients, 593 cases were diagnosed with predominantly antibody deficiencies (35.7 %), 390 cases (23.5 %) with congenital defects of phagocyte number, function, or both, 291 cases (17.5 %) with well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency, 265 cases (16 %) with combined immunodeficiencies, 40 cases (2.4 %) with diseases of immune dysregulation, 38 cases (2.3 %) with autoinflammatory disorders, 32 cases (1.9 %) with complement deficiencies, and 12 cases (0.7 %) with defects in innate immunity. Table III shows the prevalence of PID in reports from Europe, Latin America and Asia.

Discussion

The current study represents the demographic data of Iranian PID patients who were diagnosed from the March of 2006 till the March of 2013. A total number of 731 patients were registered in IPDR during this period. It is most likely that this number does not reflect the prevalence and the burden of PID in Iran due to multiple limiting factors; there is no screening test available for PID neither at the national level nor at any medical center; our registry system is hospital based and voluntary and in addition to the lack of enough immunologists, there are only a limited number of medical centers mainly in highly populated cities, which has access to sophisticated diagnostic and therapeutic techniques [11]. It is possible that patients with mild manifestations may be treated by general practitioners, pediatricians or other specialist at the private offices or clinics. On the other hand, patients with more severe types of PID like SCID may die before a definitive diagnosis is made [11, 19, 20]. Moreover, many PID patients may be referred and managed by other specialists especially in the absence of severe and recurrent infections as the main clinical presentation [21–24].

Considering the result of the current report, the distribution of different types of PID in Iran is in agreement with other reports from several countries. Predominantly antibody deficiencies were the most common group of PID similar to the reports of European, Latin American and some Asian registries including Japan, Korea and China [25–29]. It is noteworthy that these disorders were thought to be more prevalent according to the previous reports from the Europe in 2006 (66.9 % of PID cases) [11]. However, according to the recent reports from Europe [30], their prevalence became more similar to the reports from Iran (56.4 vs. 32.3 % respectively). Moreover, the percentage of Iranian PID patients with these disorders is similar in the current report and previous registry report of 2006 reducing the probable effect of incidental findings. Well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency were the second most prevalent group of PID in most of the previously reported registries [11, 21, 25, 27, 30–32]. However, in the current study, combined T- and B-cell immunodeficiencies were the second most prevalent group of PID observed in 22.3 % of cases. This finding was in agreement with the results of some PID registries of Asian countries including Qatar, China, Kuwait, Egypt and Japan with a near share of this disorders among their PID patients [25, 26, 31, 33, 34] but much higher than those of Europe and Latin America [27, 30]. Congenital defects of phagocyte number, function, or both and well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency were the third and fourth most common group of PID involving 17.4 % and 17.2 % of patients respectively. This rate is similar to the result of several reports from Asian countries including Japan, China, Oman and Qatar [26, 32, 33] but is higher than Europe, Latin America, and Australia [21, 27, 30] for congenital defects of phagocyte number, function, or both and in agreement to the results of almost all performed studies for the prevalence of well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency [25–27, 30, 31, 33, 34]. In this report, 5.2 % of PID cases were diagnosed with autoinflammatory disorders. In fact the only study which mentioned this PID group is ESID database representing the European PID registry (2 % of cases) [30]. This rate is higher than all of the previously reported studies probably due to two reasons. First, autoinflammatory disorders such as FMF were not recognized as a group of PID disorders until the IUIS classification of 2011 [9]. Second, the prevalence of such disorders, especially FMF, is mostly observed in specific genetic groups with a geographical pattern of distribution [35]. Diseases of immune dysregulation, and complement deficiencies were the least prevalent types of PID, a finding which was observed in most of the previously reported studies [21, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34].

SCID, CVID, hyper-IgE syndrome, and selective IgA deficiency were the most observed disorders in the current study. In contrast with the results of almost all other studies including previous registry reports from Iran, SCID was the most prevalent type of PID disorders in our registered patients. This finding is mainly due to the presence of numerous Azerbaijanis Turks in our study population since about 16 % of cases were registered from Azerbaijan province and it is most likely that many other patients with this ethnicity were registered from other provinces of the country. In a study by Shabestari et al. on the prevalence of PID in northwest Iran, with Azerbaijanis Turks as the main ethnic group, SCID was the most common disorder indicating a genetic background in this ethnicity which consists at least 24 % of Iran’s population [36]. Hyper-IgE syndrome was the third most observed disorder in the current registry. The higher prevalence of this disorder comparing to other reports is highly due to the higher detection as a result of some published and yet to be published studies on immunological aspects of dermatological diseases such as severe atopic dermatitis [37]. Selective IgA deficiency was more frequent in the registry reports of European countries [28, 30, 38], a finding which was in contrast with the result of studies performed in Asian countries including Japan, Iran and Australia [11, 21, 26]. The true prevalence of selective IgA deficiency may be underestimated in the mentioned studies since they were all hospital based and asymptomatic cases are not included [11, 39, 40]. In addition, patients with mild manifestation may be treated symptomatically by general practitioners without any referral to an immunologist or immunologic screening [41, 42]. In contrast, CVID patients are more prone to severe and recurrent infections and require IVIG replacement therapy in order to control the clinical course of their disease [21, 43–46]. These patients are more likely to be hospitalized, undergo additional work-ups, and refer to higher level medical centers for diagnostic and therapeutic approaches [47–49]. This phenomenon may explain the higher rate of CVID comparing to selective IgA deficiency in countries with a hospital based and voluntary registry system. There was a significant increase in the number of patients diagnosed with selective IgA deficiency. Before 2006, only 55 cases of this disorder were registered in IPIDR, while 55 new cases were included in the 7 years period of time afterwards. This trend is mainly due to the collaborations with other specialties in the field of research resulting in an increased awareness [13].

The male to female ratio of the study population was 1.65:1, similar to the previous IPIDR report in 2006 (1.7:1). This finding which is in agreement with previous reports on PID [21, 26–30] is probably due to the presence of several disorders with an X-linked pattern of inheritance such as XLA, X-linked SCID, X linked Hyper IgM syndrome, X linked lymphoproliferative diseases and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Consanguineous marriage of parents was observed in 63.1 % of cases, lower than the previous report of 2006 (68.5 %), but still much higher than the overall consanguinity rate of the country’s population (38.6 %) [50]. Consanguinity is considered to be associated with occurrence of PID, especially in disorders with autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance [11, 50, 51]. Moreover, it may affect the clinical phenotypes and onset of disease in disorders such as CVID [51, 52]. Although educational programs via multiple media methods are being already generated, cultural roots of this type of marriage remained as an obstacle in reducing the probable burden of these marriages’ outcome. In fact, despite many efforts in the field of family education, consanguineous marriages are frequently observed even in the relatives of some registered Iranian PID patients. Family history of death at an early age without a known cause was observed in 26.1 % of our cases. It is likely that the majority of these cases also suffered from PID but did not undergo mandatory diagnostic approaches for a definitive diagnosis.

Most of the cases diagnosed with PID are children [11]. In accordance with other studies, most of our cases were diagnosed in childhood and about 60 % were diagnosed by the age of 2 years. Early diagnosis and management of PID can result in decreased rate of morbidity and mortality, and a higher quality of life in PID patients [13, 53, 54]. There was a reverse association between the birth year of patients and the diagnostic delay showing a decreased diagnostic delay in the previous years. A same association was also observed in the previous report of IPIDR and also in the registry report of France over a 30 years period of time [11, 28]. Registration of Iranian PID patients might have played a main role in reducing the diagnostic delay since it increased the awareness of medical staff regarding such disorders as well as providing mandatory diagnostic techniques to cover a larger portion of the country’s population [11, 55]. Moreover, training of new clinical immunologists in the country and national wide media programs specially in immunology week are other factors resulting in an increased awareness of PID among Iranian population [13, 56].

The mortality rate of our study population was 18.7 % similar to the previous report of IPIDR in 2006 with a mortality rate of 17.2 %. It should be kept in mind that the true mortality rate in the follow-up period may be higher since patients who did not refer for follow-up or could not be located at the end of the study are more likely to be dead than the followed patients [57], especially in disorders like SCID with a severe and rapid course of disease. Iranian SCID patients suffer a high mortality rate due to the lack of enough bone marrow transplantation facilities and matched donors. Moreover, the short duration of follow-up could result in underestimation of mortality and should be compared to studies with a similar duration of follow-up. In fact, it is most likely that the mortality rate of this study is much higher than the previous report of 30 years from Iran due to its shorter follow-up period. Comparing the results of this study with other reports with a similar follow-up period, Wang et al. reported a mortality rate of 12.3 % in a study on Chinese PID patients during 2004 to 2009 [25]. Rhim et al. reported a mortality rate of 9.8 % among Korean PID patients during 2001 to 2005 [29]. Al-Herz et al. also reported a mortality rate 19.7 % in their study on Kuwaiti PID patients registered during 2004 to 2006 [31]. Although such studies demonstrated a similar mortality rate comparing to the current study, an accurate assessment of the outcome of PID in Iranian patients can only be achieved after establishing a national wide system for registration of death certifications similar to some countries such as Australia [21, 58].

Conclusion

Registration of Iranian PID patients has increased the awareness of Iranian medical community regarding such rare disorders resulting in reduced diagnostic delay. Providing diagnostic and therapeutic methods for a larger portion of the country’s population necessitates the enrollment of more contributing medical centers especially in areas of need. This step is also mandatory for a more accurate epidemiologic evaluation of PID in Iran.

References

Durandy A, Kracker S, Fischer A. Primary antibody deficiencies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:519.

Durandy A, Taubenheim N, Peron S, Fischer A. Pathophysiology of B-cell intrinsic immunoglobulin class switch recombination deficiencies. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:275.

Chinen J, Notarangelo LD, Shearer WT. Advances in basic and clinical immunology in 2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:675.

Pieper K, Grimbacher B, Eibel H. B-cell biology and development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:959.

Rezaei N, Hedayat M, Aghamohammadi A, Nichols KE. Primary immunodeficiency diseases associated with increased susceptibility to viral infections and malignancies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1329.

Aghamohammadi A, Abolhassani H, Mohammadinejad P, Rezaei N. The approach to children with recurrent infections. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;11:89.

Abolhassani H, Aghamohammadi A, Imanzadeh A, Mohammadinejad P, Sadeghi B, Rezaei N. Malignancy phenotype in common variable immunodeficiency. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012;22:133.

Behniafard N, Aghamohammadi A, Abolhassani H, Pourjabbar S, Sabouni F, Rezaei N. Autoimmunity in X-linked agammaglobulinemia: Kawasaki disease and review of the literature. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8:155.

Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Casanova JL, Chapel H, Conley ME, Cunningham-Rundles C, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update on the classification from the international union of immunological societies expert committee for primary immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. 2011;2:54.

Parvaneh N, Casanova JL, Notarangelo LD, Conley ME. Primary immunodeficiencies: a rapidly evolving story. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:314.

Rezaei N, Aghamohammadi A, Moin M, Pourpak Z, Movahedi M, Gharagozlou M, et al. Frequency and clinical manifestations of patients with primary immunodeficiency disorders in Iran: update from the Iranian Primary Immunodeficiency Registry. J Clin Immunol. 2006;26:519.

Bousfiha AA, Jeddane L, Ailal F, Benhsaien I, Mahlaoui N, Casanova JL, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases worldwide: more common than generally thought. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33:1.

Rezaei N, Mohammadinejad P, Aghamohammadi A. The demographics of primary immunodeficiency diseases across the unique ethnic groups in Iran, and approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1238:24.

Nourijelyani K, Aghamohammadi A, Salehi Sadaghiani M, Behniafard N, Abolhassani H, Pourjabar S, et al. Physicians awareness on primary immunodeficiency disorders in Iran. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;11:57.

Al-Herz W, Zainal ME, Salama M, Al-Ateeqi W, Husain K, Abdul-Rasoul M, et al. Primary immunodeficiency disorders: survey of pediatricians in Kuwait. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:379.

Boyle JM, Buckley RH. Population prevalence of diagnosed primary immunodeficiency diseases in the United States. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27:497.

Aghamohammadi A, Moein M, Farhoudi A, Pourpak Z, Rezaei N, Abolmaali K, et al. Primary immunodeficiency in Iran: first report of the National Registry of PID in children and adults. J Clin Immunol. 2002;22:375.

Conley ME, Notarangelo LD, Etzioni A. Diagnostic criteria for primary immunodeficiencies. Representing PAGID (Pan-American Group for Immunodeficiency) and ESID (European Society for Immunodeficiencies). Clin Immunol. 1999;93:190.

Srinivasa BT, Alizadehfar R, Desrosiers M, Shuster J, Pai NP, Tsoukas CM. Adult primary immune deficiency: what are we missing? Am J Med. 2012;125:779.

Al-Herz W, Zainal ME, Alenezi HM, Husain K, Alshemmari SH. Performance status and deaths among children registered in Kuwait National Primary ImmunoDeficiency Disorders Registry. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2010;28:141.

Kirkpatrick P, Riminton S. Primary immunodeficiency diseases in Australia and New Zealand. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27:517.

Mamishi S, Eghbali AN, Rezaei N, Abolhassani H, Parvaneh N, Aghamohammadi A. A single center 14 years study of infectious complications leading to hospitalization of patients with primary antibody deficiencies. Braz J Infect Dis. 2010;14:351.

Litzman J, Stikarovska D, Pikulova Z, Pavlik T, Pesak S, Thon V, et al. Change in referral diagnoses and diagnostic delay in hypogammaglobulinaemic patients during 28 years in a single referral centre. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;153:95.

Garcia JM, Gamboa P, de la Calle A, Hernandez MD, Caballero MT, Garcia BE, et al. Diagnosis and management of immunodeficiencies in adults by allergologists. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010;20:185.

Wang LL, Jin YY, Hao YQ, Wang JJ, Yao CM, Wang X, et al. Distribution and clinical features of primary immunodeficiency diseases in Chinese children (2004–2009). J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:297.

Ishimura M, Takada H, Doi T, Imai K, Sasahara Y, Kanegane H, et al. Nationwide survey of patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases in Japan. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:968.

Leiva LE, Zelazco M, Oleastro M, Carneiro-Sampaio M, Condino-Neto A, Costa-Carvalho BT, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases in Latin America: the second report of the LAGID registry. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27:101.

CEREDIH: The French PID study group. The French national registry of primary immunodeficiency diseases. Clin Immunol. 2010;135:264–72.

Rhim JW, Kim KH, Kim DS, Kim BS, Kim JS, Kim CH, et al. Prevalence of primary immunodeficiency in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:788.

ESID database statistics. In: European Society for Immunodeficiencies. 2013. http://www.esid.org/statistics.php. Accessed 26 Mar 2012

Al-Herz W. Primary immunodeficiency disorders in Kuwait: first report from Kuwait National Primary Immunodeficiency Registry (2004–2006). J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:186.

Al-Tamemi S, Elnour I, Dennison D. Primary immunodeficiency diseases in oman: five years’ experience at sultan qaboos university hospital. World Allergy Organ J. 2012;5:52.

Ehlayel MS, Bener A, Laban MA. Primary immunodeficiency diseases in children: 15 year experience in a tertiary care medical center in Qatar. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33:317.

Reda SM, Afifi HM, Amine MM. Primary immunodeficiency diseases in Egyptian children: a single-center study. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29:343.

Zadeh N, Getzug T, Grody WW. Diagnosis and management of familial Mediterranean fever: integrating medical genetics in a dedicated interdisciplinary clinic. Genet Med. 2011;13:263.

Shabestari MS, Maljaei SH, Baradaran R, Barzegar M, Hashemi F, Mesri A, et al. Distribution of primary immunodeficiency diseases in the Turk ethnic group, living in the northwestern Iran. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27:510.

Aghamohammadi A, Moghaddam ZG, Abolhassani H, Hallaji Z, Mortazavi H, Pourhamdi S, et al. Investigation of underlying primary immunodeficiencies in patients with severe atopic dermatitis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2013. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2013.02.004.

Nikfarjam J, Pourpak Z, Shahrabi M, Nikfarjam L, Kouhkan A, Moazeni M, et al. Oral manifestations in selective IgA deficiency. Int J Dent Hyg. 2004;2:19.

Mohammadi J, Ramanujam R, Jarefors S, Rezaei N, Aghamohammadi A, Gregersen PK, et al. IgA deficiency and the MHC: assessment of relative risk and microheterogeneity within the HLA A1 B8, DR3 (8.1) haplotype. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:138.

Aghamohammadi A, Cheraghi T, Gharagozlou M, Movahedi M, Rezaei N, Yeganeh M, et al. IgA deficiency: correlation between clinical and immunological phenotypes. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29:130.

Soheili H, Abolhassani H, Arandi N, Khazaei HA, Shahinpour S, Hirbod-Mobarakeh A, et al. Evaluation of natural regulatory T cells in subjects with selective IgA deficiency: from senior idea to novel opportunities. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;160:208.

Aghamohammadi A, Abolhassani H, Biglari M, Abolmaali S, Moazzami K, Tabatabaeiyan M, et al. Analysis of switched memory B cells in patients with IgA deficiency. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;156:462.

Rahiminejad MS, Mirmohammad Sadeghi M, Mohammadinejad P, Sadeghi B, Abolhassani H, Dehghani Firoozabadi MM, et al. Evaluation of humoral immune function in patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;12:50.

Rezaei N, Abolhassani H, Aghamohammadi A, Ochs HD. Indications and safety of intravenous and subcutaneous immunoglobulin therapy. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7:301.

Dashti-Khavidaki S, Aghamohammadi A, Farshadi F, Movahedi M, Parvaneh N, Pouladi N, et al. Adverse reactions of prophylactic intravenous immunoglobulin; a 13-year experience with 3004 infusions in Iranian patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009;19:139.

Aghamohammadi A, Farhoudi A, Nikzad M, Moin M, Pourpak Z, Rezaei N, et al. Adverse reactions of prophylactic intravenous immunoglobulin infusions in Iranian patients with primary immunodeficiency. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;92:60.

Abolhassani H, Sadaghiani MS, Aghamohammadi A, Ochs HD, Rezaei N. Home-based subcutaneous immunoglobulin versus hospital-based intravenous immunoglobulin in treatment of primary antibody deficiencies: systematic review and meta analysis. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:1180.

Aghamohammadi A, Abolhassani H, Moazzami K, Parvaneh N, Rezaei N. Correlation between common variable immunodeficiency clinical phenotypes and parental consanguinity in children and adults. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010;20:372.

Salek Farrokhi A, Aghamohammadi A, Pourhamdi S, Mohammadinejad P, Abolhassani H, Moazzeni SM. Evaluation of class switch recombination in B lymphocytes of patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Immunol Methods. 2013;394:94.

Rezaei N, Pourpak Z, Aghamohammadi A, Farhoudi A, Movahedi M, Gharagozlou M, et al. Consanguinity in primary immunodeficiency disorders; the report from Iranian Primary Immunodeficiency Registry. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2006;56:145.

Rezaei N, Abolhassani H, Kasraian A, Mohammadinejad P, Sadeghi B, Aghamohammadi A. Family study of pediatric patients with primary antibody deficiencies. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;12:377.

Rivoisy C, Gerard L, Boutboul D, Malphettes M, Fieschi C, Durieu I, et al. Parental consanguinity is associated with a severe phenotype in common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:98.

Zebracki K, Palermo TM, Hostoffer R, Duff K, Drotar D. Health-related quality of life of children with primary immunodeficiency disease: a comparison study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93:557.

Abolhassani H, Aghamohammadi A, Abolhassani F, Eftekhar H, Heidarnia M, Rezaei N. Health policy for common variable immunodeficiency: burden of the disease. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21:454.

Aghamohammadi A, Bahrami A, Mamishi S, Mohammadi B, Abolhassani H, Parvaneh N, et al. Impact of delayed diagnosis in children with primary antibody deficiencies. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011;44:229.

Aghamohammadi A, Montazeri A, Abolhassani H, Saroukhani S, Pourjabbar S, Tavassoli M, et al. Health-related quality of life in primary antibody deficiency. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;10:47.

Mohammadinejad P, Aghamohammadi A, Abolhassani H, Sadaghiani MS, Abdollahzade S, Sadeghi B, et al. Pediatric patients with common variable immunodeficiency: long-term follow-up. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012;22:208.

Vajdic CM, Mao L, van Leeuwen MT, Kirkpatrick P, Grulich AE, Riminton S. Are antibody deficiency disorders associated with a narrower range of cancers than other forms of immunodeficiency? Blood. 2010;116:1228.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aghamohammadi, A., Mohammadinejad, P., Abolhassani, H. et al. Primary Immunodeficiency Disorders in Iran: Update and New Insights from the Third Report of the National Registry. J Clin Immunol 34, 478–490 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-014-0001-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-014-0001-z