Abstract

To summarize the published evidence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) bone and joint infections. PubMed and Scopus electronic databases were searched. The annual incidence of invasive CA-MRSA infections ranged from 1.6 to 29.7 cases per 100,000, depending on the location of the population studied; bone and joint infections accounted for 2.8 to 43 % of invasive CA-MRSA infections. Surveillance studies showed that patients <2 years of age are mainly affected. Incidence rates were higher in blacks. Sixty-seven case reports and case series were identified; the majority of the patients included were children. Vancomycin and clindamycin were used effectively, in addition to surgical interventions. Seven patients out of 413 died (1.7 %) in total. Chronic osteomyelitis developed in 19 patients (data for 164 patients were available). The published evidence for CA-MRSA bone and joint infections refers mainly to children; their incidence depends on the location and race of the population. Vancomycin and clindamycin have been used effectively for their treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Worldwide, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains are among the most commonly isolated bacteria in patients requiring hospitalization or with significant healthcare exposure (HA-MRSA) [1–3]. The presence of the mecA gene, which induces resistance to almost all β-lactams is probably one of their most important characteristics [4]. At the turn of the 20th century, the first reports of community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) infections among healthy individuals (with no identifiable risk factors for HA-MRSA infections) and among injection drug users, incarcerated people, and athletes were published [5, 6].

Strains of MRSA are more frequently associated with skin and soft tissue infections, but more invasive infections, including bone and joint infections, also occur [4, 7]. In fact, MRSA has been identified as one of the most common causes of bone and joint infections [8, 9]. During the last decade CA-MRSA strains have been reported to be responsible for osteomyelitis or septic arthritis [10]. We sought to review systematically the available evidence in order to identify the incidence, characteristics, and outcomes of patients with CA-MRSA in bone and joint infections.

Materials and methods

Data sources

The studies included in this review were retrieved from searches performed in PubMed and Scopus (up to May 2012), using the search terms “bone and joint infections,” “osteomyelitis,” “septic arthritis,” “spondylodiscitis,” “spondylitis,” “bursitis,” “discitis” in combination with the terms “community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus” or “community-associated MRSA.” References of the retrieved articles and relevant reviews were also hand-searched.

Study selection criteria

Studies reporting data on the incidence, characteristics, and outcomes of patients with CA-MRSA bone and joint infections were included in this review. Therefore, studies of any design that enrolled patients of any age could be included. Prosthetic joint infections were also eligible. Abstracts of scientific conferences and studies published in languages other than English, Italian, German, Greek, French, and Spanish were excluded. Studies not fulfilling the definition of CA-MRSA infection (as described below) were excluded, even if the titles indicated that they were reporting data on patients with CA-MRSA bone and joint infection.

Definitions

A case of CA-MRSA bone or joint infection was defined as disease compatible with osteomyelitis or septic arthritis, in which MRSA was cultured from blood, synovial fluid, or bone biopsy. A culture from wound or abscess was eligible in cases of clinically and/or radiographically diagnosed bone or joint infections complicated with abscess formation or fistula. The culture should have been taken in an outpatient setting or within 48 h after hospital admission, and with none of the following healthcare risk factors: use of broad spectrum antibiotics during the previous 6 months, recent hospitalization, residence in a long-term care facility, dialysis, surgery 1 year before the onset of illness or permanent indwelling catheter or percutaneous medical device [11]. Moreover, the definition was broadened to include cases in which the molecular typing methods (pulsed-field gel electrophoresis [PFGE], multi locus sequence typing [MLST] or other techniques) provided evidence of a community-associated strain. This was allowed in order to study the potential penetration of MRSA strains with “community-associated” characteristics into the hospital environment.

Results

Epidemiology incidence of CA-MRSA bone/joint infections

A population-based surveillance program in Atlanta (GA, USA) and Baltimore (MD, USA) and a hospital laboratory sentinel surveillance of 12 hospitals in Minnesota (USA) performed in 2001 and 2002 showed that the annual incidence of invasive CA-MRSA infections was 25.7 cases per 100,000 in Atlanta and 18.0 per 100,000 in Baltimore. Bone and joint infections were responsible for 2.8 % of these cases in Atlanta, 5 % in Baltimore and 6 % in Minnesota. In both Atlanta and Baltimore CA-MRSA were more common in patients aged <2 years; in Atlanta CA-MRSA infections were more common among blacks than whites in all age groups [12]. In the Active Bacterial Core surveillance system during 2004–2005 the annual incidence of invasive CA-MRSA infections ranged between 1.6 and 29.7 per 100,000 among different regions. In this surveillance, the higher incidence was seen in patients aged >65 years (8.9 per 100,000) and the lower in patients aged 2–17 years (0.6-0.8 per 100,000) [13]. Osteomyelitis accounted for 8.1 % of all cases. Finally, data from a prospective surveillance in Sweden showed that during the period 2003–2005 the annual incidence of CA-MRSA-invasive infections was 16.6 per 100,000; bone and joint infections accounted for 43 % of the cases [14].

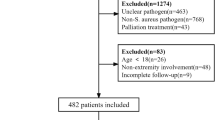

Selected studies

The searches performed in PubMed and Scopus generated a total of 130 and 233 search results respectively. The process of study selection is shown in details in Fig. 1. A total of 67 studies were included in the review [5, 15–80].

Case reports of CA-MRSA bone/joint infections

Table 1 summarizes the data available from patients described in case reports of CA-MRSA bone and joint infections; data for 45 patients from 35 reports were available [15, 17, 19, 24, 25, 27, 31, 34, 36, 38, 39, 41, 42, 44–48, 51, 52, 54–57, 61, 62, 65–68, 71, 73, 80]. The majority of the patients were young (25 out of 45 [56 %] were children ≤14 years, 30 out of 45 [67 %] were younger than 30 years old and almost all [44 out of 45, 98 %] were younger than 65 years). Most of them were male (31 out of 45, 69 %) with no known risk factors for CA-MRSA infections except for a history of skin and soft tissue infections (12 out of 42, 29 %). The median duration of symptoms prior to the diagnosis or hospitalization was 6 days. Fever, local tenderness, and articular disability were the main symptoms. Osteomyelitis was the main diagnosis (either alone [32 out of 45, 71 %] or in combination with septic arthritis [4 out of 45, 9 %]). Long bones were mainly affected followed by vertebrae. Diagnosis was confirmed by X-rays, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or scintigraphy. Further microbiological studies for the identification of toxins (Panton–Valentine leukocidin [PVL] positive in 14 out of 17) and typing (according to SCCmec type and MLST) was performed in 38 % of the cases. SCCmec IV was the predominant or sole type in all studies.

The majority of patients had bacteremia (27 out of 45, 60 %) with or without local complications, including abscesses, pyomyositis, and deep venous thrombosis. Sixteen patients had systemic complications, either on admission or during treatment; 13 patients had pulmonary complications (mainly septic emboli and pleural effusion), 4 patients had central nervous system and 3 cardiac involvement.

The empirical treatment (before the culture results were available) was provided for 29 cases; in 16 of them (55 %) the empirical regimen did not include an antibiotic effective against MRSA. Following treatment that employed surgical interventions in 24 patients (59 %) and antibiotics in all patients (mainly vancomycin [36 out of 42, 88 %] and in some cases clindamycin, fusidic acid, linezolid, fosfomycin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or teicoplanin) for a median duration of 8 weeks (range 1–30), the majority of patients were cured (39 out of 44, 87.5 %), while 3 patients died (8 %). Two patients died during the first week of the hospital stay; 1 had chronic kidney disease and diabetes and 1 developed respiratory insufficiency due to septic emboli. The last patient died on week 5: a 7-year-old girl who developed respiratory insufficiency. Four recurrences were reported, one of which was finally cured, and the other resulted in chronic osteomyelitis. Local complications at the end of treatment included pathological fractures in 7 patients and chronic osteomyelitis in 3.

Case series of CA-MRSA bone/joint infections

We identified 33 case series that included 510 patients with CA-MRSA bone and joint infections [16, 18, 20–23, 26, 28–30, 32–35, 37, 43, 49, 50, 53, 58–60, 63, 64, 69, 70, 72, 74–79]. The majority of the case series included described patients with bone and joint infections due to several pathogens and also included patients with MRSA osteoarticular infections. Therefore, specific data regarding patients with MRSA infections were limited (Table 2). Most of the studies included were performed on children (488 out of 510 patients, 96 %) [16, 18, 20–23, 26, 29, 30, 32–35, 37, 49, 50, 58–60, 63, 64, 69, 70, 72, 76–79], and only 5 included adults [28, 43, 53, 74, 75]. In studies that provided data, bacteremia was present in most of the patients (45–100 %) [18, 21, 22, 34, 35, 49, 50, 59, 60, 63, 72], while DVT was the major complication in 6 of them (4 % in the largest study that provided data [16], up to 100 % in small case series [22, 26, 34, 35, 49, 59, 63, 72, 76]. PVL was present in 166 out of 172 (97 %) of isolates in which it was tested. SCCmec IV USA300 was the predominant clone in the few studies that provided relevant data. One study from France reported that the European clone ST 80 was isolated. Surgical interventions were required in 202 out of 236 (86 %) of patients for whom data were available. Vancomycin and clindamycin were the most commonly prescribed antibiotics. Four patients died (4 out of 370, 1 %) and 16 out of 126 (13 %) developed chronic osteomyelitis.

Discussion

There are limited data regarding the annual incidence of CA-MRSA bone and joint infections. The available evidence shows that it varies according to the location and age of the studied population. Thus, the incidence of invasive CA-MRSA ranged from 1.6 to 29.7 cases per 100,000, while bone and joint infections accounted for 2.8 to 43 % of invasive CA-MRSA infections. In addition, surveillance studies showed that these infections affect mainly patients <2 years of age; the distribution of infections in other age populations depends on the study site and race. However, it seems that black race is associated with a higher risk of infections than white.

The published evidence from case reports and case series suggested that the majority of patients of CA-MRSA bone and joint infections were cured. A total of seven deaths were reported; 3 in case reports and 4 in case series. On the other hand, complications were relatively common; abscesses, pyomyositis, DVT, and chronic osteomyelitis were the most common local complications. Although systemic complications were also frequent (39 % in case reports), this did not seem to affect mortality. As expected, prolonged antibiotic treatment and hospitalization were employed in most of the cases.

Vancomycin was the most frequently used antibiotic in both case reports and case series. However, clindamycin monotherapy was also used effectively in case series as well as in combination with or following initial vancomycin treatment [16, 49, 50, 69, 72]. In these case series, inducible resistance to clindamycin was not detected. Vancomycin is the treatment of choice for MRSA bone and joint infections [81, 82]. However, specific data regarding the most effective treatment option for CA-MRSA infections are not available. Linezolid, teicoplanin, and daptomycin are alternative options that have been used effectively for the treatment of MRSA bone and joint infections [83–87].

S. aureus is the most commonly isolated pathogen from bone and joint infections [4, 7, 81, 82]. During the last decade, several studies showed that S. aureus infections increased, and the relative frequency of MRSA increase was more prominent than that of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), both in the community and in hospitals [88–90]. Therefore, it seems prudent to include in the empirical antibiotic regimen a drug that is effective against MRSA. In the limited available data in this review, approximately 50 % of patients did not receive appropriate empirical treatment. Fortunately, this did not seem to have an impact on mortality. However, complications were frequent. Owing to the limited data available, we were unable to identify whether or not the use of appropriate treatment could be associated with fewer complications. A recent review reported that MRSA osteomyelitis in children was associated with more DVTs than MSSA osteomyelitis [91].

Most of the patients included in the present review did not have risk factors for CA-MRSA infection, in accordance with previously published studies [92, 93]. Moreover, a site of entry was not identified, suggesting a hematogenous shedding of MRSA. Hematogenous osteomyelitis of long bones is most commonly seen in children, as was the case in this review. In addition, the propensity of CA-MRSA toward younger individuals has been confirmed in this review. The great majority in both case reports and case series were children. On the contrary, we have previously reported that the majority of published cases of CA-MRSA pneumonia were young adults [92, 93]. Other differences between the two reports included the higher severity of complications and mortality reported in patients with pneumonia.

One study provided data for 5 patients with CA-MRSA prosthetic joint infections [43]. All infections developed early after joint replacement. All patients required replacement of the affected joint and prolonged antibiotic therapy. The isolated strains had identical antibiograms. Molecular characterization of two of them revealed a PFGE type that was identical to the USA300 clone, SCCmec type IV. This report provides further evidence that “community-associated” strains have been identified as a cause of healthcare-associated or hospital-associated infections [94–96].

In conclusion, the currently limited available evidence from case reports and studies with different study designs and patients’ characteristics suggests that the incidence of bone and joint infections caused by CA-MRSA varies and depends on the geographic region (even within the same country), age, and race of the population. A propensity toward younger individuals is evident. The currently available treatment options seem to be adequately effective. However, the increase in the number of CA-MRSA infections both in the community and in the hospital among patients with no known risk factors requires increased awareness for early recognition and treatment.

References

National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) (2004) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control 32:470–485

Chambers HF (2001) The changing epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus? Emerg Infect Dis 7:178–182

Grundmann H, Aires-de-Sousa M, Boyce J, Tiemersma E (2006) Emergence and resurgence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a public-health threat. Lancet 368:874–885

Zetola N, Francis JS, Nuermberger EL, Bishai WR (2005) Community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an emerging threat. Lancet Infect Dis 5:275–286

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999) Four pediatric deaths from community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-Minnesota and North Dakota, 1997–1999. JAMA 282:1123–1125

Herold BC, Immergluck LC, Maranan MC et al (1998) Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children with no identified predisposing risk. JAMA 279:593–598

Kowalski TJ, Berbari EF, Osmon DR (2005) Epidemiology, treatment, and prevention of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Mayo Clin Proc 80:1201–1207, quiz 8

Archer GL (1998) Staphylococcus aureus: a well-armed pathogen. Clin Infect Dis 26:1179–1181

Baker ADL, Macnicol MF (2008) Haematogenous osteomyelitis in children: epidemiology, classification, aetiology and treatment. J Paediatr Child Health 18:75–84

Deleo FR, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF (2010) Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 375:1557–1568

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004) Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in Pacific Islanders—Hawaii, 2001–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 53:767–70

Fridkin SK, Hageman JC, Morrison M et al (2005) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in three communities. N Engl J Med 352:1436–1444

Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J et al (2007) Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 298:1763–1771

Jacobsson G, Dashti S, Wahlberg T, Andersson R (2007) The epidemiology of and risk factors for invasive Staphylococcus aureus infections in western Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis 39:6–13

Ahamed Puthiyaveetil S (2009) Osteomyelitis—a case report. Aust Fam Physician 38:521–523

Arnold SR, Elias D, Buckingham SC et al (2006) Changing patterns of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis and septic arthritis: emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Pediatr Orthop 26:703–708

Ash N, Salai M, Aphter S, Olchovsky D (1995) Primary psoas abscess due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus concurrent with septic arthritis of the hip joint. South Med J 88:863–865

Bocchini CE, Hulten KG, Mason EO Jr, Gonzalez BE, Hammerman WA, Kaplan SL (2006) Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes are associated with enhanced inflammatory response and local disease in acute hematogenous Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis in children. Pediatrics 117:433–440

Bukhari EE, Al-Otaibi FE (2009) Severe community-acquired infection caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Saudi Arabian children. Saudi Med J 30:1595–1600

Carrillo-Marquez MA, Hulten KG, Hammerman W, Mason EO, Kaplan SL (2009) USA300 is the predominant genotype causing Staphylococcus aureus septic arthritis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 28:1076–1080

Castaldo ET, Yang EY (2007) Severe sepsis attributable to community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an emerging fatal problem. Am Surg 73:684–687, discussion 7–8

Chen CJ, Su LH, Chiu CH et al (2007) Clinical features and molecular characteristics of invasive community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in Taiwanese children. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 59:287–293

Chen WL, Chang WN, Chen YS et al (2010) Acute community-acquired osteoarticular infections in children: high incidence of concomitant bone and joint involvement. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 43:332–338

Cherian MP (2008) Invasive community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection causing bacteremia and osteomyelitis simultaneously in two Saudi siblings. Pediatr Infect Dis J 27:272–278

Contreras GA, Perez N, Murphy JR, Cleary TG, Heresi GP (2009) Empyema necessitans and acute osteomyelitis associated with community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an infant. Biomedica 29:506–512

Crary SE, Buchanan GR, Drake CE, Journeycake JM (2006) Venous thrombosis and thromboembolism in children with osteomyelitis. J Pediatr 149:537–541

Crum NF (2005) The emergence of severe, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Scand J Infect Dis 37:651–656

D’Agostino C, Scorzolini L, Massetti AP et al (2010) A seven-year prospective study on spondylodiscitis: epidemiological and microbiological features. Infection 38:102–107

Dohin B, Gillet Y, Kohler R et al (2007) Pediatric bone and joint infections caused by Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatr Infect Dis J 26:1042–1048

Fang YH, Hsueh PR, Hu JJ et al (2004) Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children in northern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 37:29–34

Gelfand MS, Cleveland KO, Heck RK, Goswami R (2006) Pathological fracture in acute osteomyelitis of long bones secondary to community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: two cases and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci 332:357–360

Goergens ED, McEvoy A, Watson M, Barrett IR (2005) Acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children. J Paediatr Child Health 41:59–62

Gonzalez BE, Hulten KG, Dishop MK et al (2005) Pulmonary manifestations in children with invasive community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis 41:583–590

Gonzalez BE, Martinez-Aguilar G, Hulten KG et al (2005) Severe Staphylococcal sepsis in adolescents in the era of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatrics 115:642–648

Gonzalez BE, Teruya J, Mahoney DH Jr et al (2006) Venous thrombosis associated with staphylococcal osteomyelitis in children. Pediatrics 117:1673–1679

Graber CJ, Wong MK, Carleton HA, Perdreau-Remington F, Haller BL, Chambers HF (2007) Intermediate vancomycin susceptibility in a community-associated MRSA clone. Emerg Infect Dis 13:491–493

Hawkshead JJ 3rd, Patel NB, Steele RW, Heinrich SD (2009) Comparative severity of pediatric osteomyelitis attributable to methicillin-resistant versus methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. J Pediatr Orthop 29:85–90

Hsu LY, Koh TH, Tan TY et al (2006) Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Singapore: a further six cases. Singapore Med J 47:20–26

Kallarackal G, Lawson TM, Williams BD (2000) Community-acquired septic arthritis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 39:1304–1305

Kara A, Tezer H, Devrim I et al (2007) Primary sternal osteomyelitis in a healthy child due to community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and literature review. Scand J Infect Dis 39:469–472

Karapinar B, Ciftdogan DY, Bayram N, Aydogdu S, Vardar F (2009) Septic pulmonary emboli secondary to disseminated, community-acquired, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Pediatr Infect Dis 4:417–420

Kefala-Agoropoulou K, Protonotariou E, Vitti D et al (2010) Life-threatening infection due to community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: case report and review. Eur J Pediatr 169:47–53

Kourbatova EV, Halvosa JS, King MD, Ray SM, White N, Blumberg HM (2005) Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA 300 clone as a cause of health care-associated infections among patients with prosthetic joint infections. Am J Infect Control 33:385–391

Kuhfahl KJ, Fasano C, Deitch K (2009) Scapular abscess, septic emboli, and deep vein thrombosis in a healthy child due to community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: case report. Pediatr Emerg Care 25:677–680

Kulkarni GB, Pal PK, Veena Kumari HB et al (2009) Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pyomyositis with myelitis: A rare occurrence with diverse presentation. Neurol India 57:653–656

Lee MC, Tashjian RZ, Eberson CP (2007) Calcaneus osteomyelitis from community-acquired MRSA. Foot Ankle Int 28:276–280

Lin MY, Rezai K, Schwartz DN (2008) Septic pulmonary emboli and bacteremia associated with deep tissue infections caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 46:1553–1555

Luque Moreno A, Duran Nunez A, Bergada Maso A, Frick A, Galles C (2008) Community-acquired, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus acute osteomyelitis and pneumonia. An Pediatr (Barc) 68:373–376

Martinez-Aguilar G, Avalos-Mishaan A, Hulten K, Hammerman W, Mason EO Jr, Kaplan SL (2004) Community-acquired, methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 23:701–706

Martinez-Aguilar G, Hammerman WA, Mason EO Jr, Kaplan SL (2003) Clindamycin treatment of invasive infections caused by community-acquired, methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 22:593–598

Menif K, Bouziri A, Borgi A, Khaldi A, Ben Hassine L, Ben Jaballah N (2011) Community acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus preseptal cellulitis complicated by zygomatic osteomylitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis and meningitis in a healthy child. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 30:252–256

Mergenhagen KA, Pasko MT (2007) Daptomycin use after vancomycin-induced neutropenia in a patient with left-sided endocarditis. Ann Pharmacother 41:1531–1535

Moore CL, Hingwe A, Donabedian SM et al (2009) Comparative evaluation of epidemiology and outcomes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) USA300 infections causing community- and healthcare-associated infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 34:148–155

Ulug M, Ayaz C, Celen MK (2011) A case report and literature review: osteomyelitis caused by community-associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dev Ctries 5:896–900

Nourse C, Starr M, Munckhof W (2007) Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus causes severe disseminated infection and deep venous thrombosis in children: literature review and recommendations for management. J Paediatr Child Health 43:656–661

Okubo T, Yabe S, Otsuka T et al (2008) Multifocal pelvic abscesses and osteomyelitis from community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a 17-year-old basketball player. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 60:313–318

Olson DP, Soares S, Kanade SV (2011) Community-acquired MRSA pyomyositis: case report and review of the literature. J Trop Med 2011:970848

Paganini H, Della Latta MP, Muller Opet B et al (2008) Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in children: multicenter trial. Arch Argent Pediatr 106:397–403

Palombarani S, Gardella N, Tuduri A et al (2007) Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in a hospital for acute diseases. Rev Argent Microbiol 39:151–155

Peleg AY, Munckhof WJ, Kleinschmidt SL, Stephens AJ, Huygens F (2005) Life-threatening community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in Australia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 24:384–387

Pezzo S, Edwards CM (2008) Community-acquired, Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus Osteomyelitis secondary to a Hematogenous source case report and review. Infect Dis Clin Pract 16:398–400

Rozenbaum R, Sampaio MG, Batista GS et al (2009) The first report in Brazil of severe infection caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). Braz J Med Biol Res 42:756–760

Saavedra-Lozano J, Mejias A, Ahmad N et al (2008) Changing trends in acute osteomyelitis in children: impact of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. J Pediatr Orthop 28:569–575

Sdougkos G, Chini V, Papanastasiou DA et al (2007) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus producing Panton-Valentine leukocidin as a cause of acute osteomyelitis in children. Clin Microbiol Infect 13:651–654

Seybold U, Talati NJ, Kizilbash Q, Shah M, Blumberg HM, Franco-Paredes C (2007) Hematogenous osteomyelitis mimicking osteosarcoma due to Community Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infection 35:190–193

Shedek BK, Nilles EJ (2008) Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pyomyositis complicated by compartment syndrome in an immunocompetent young woman. Am J Emerg Med 26:737.e3–4

Soderquist B, Berglund C (2008) Simultaneous presence of an invasive and a carrier strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a family. Scand J Infect Dis 40:987–989

Stevens QE, Seibly JM, Chen YH, Dickerman RD, Noel J, Kattner KA (2007) Reactivation of dormant lumbar methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis after 12 years. J Clin Neurosci 14:585–589

Taylor ZW, Ryan DD, Ross LA (2010) Increased incidence of sacroiliac joint infection at a children’s hospital. J Pediatr Orthop 30:893–898

Trifa M, Bouchoucha S, Smaoui H, et al (2011) Microbiological profile of haematogenous osteoarticular infections in children. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 97:186–190

Tseng MH, Lin WJ, Teng CS, Wang CC (2004) Primary sternal osteomyelitis due to community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: case report and literature review. Eur J Pediatr 163:651–653

Vander Have KL, Karmazyn B, Verma M et al (2009) Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in acute musculoskeletal infection in children: a game changer. J Pediatr Orthop 29:927–931

Wang CM, Chuang CH, Chiu CH (2005) Community-acquired disseminated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection: case report and clinical implications. Ann Trop Paediatr 25:53–57

Wang SH, Sun ZL, Guo YJ et al (2010) Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from foot ulcers in diabetic patients in a Chinese care hospital: risk factors for infection and prevalence. J Med Microbiol 59:1219–1224

White HA, Davis JS, Kittler P, Currie BJ (2011) Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy-treated bone and joint infections in a tropical setting. Intern Med J 41:668–673

Williams DJ, Deis JN, Tardy J, Creech CB (2011) Culture-negative osteoarticular infections in the era of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatr Infect Dis J 30:523–525

Wong KS, Lin TY, Huang YC, Hsia SH, Yang PH, Chu SM (2002) Clinical and radiographic spectrum of septic pulmonary embolism. Arch Dis Child 87:312–315

Yamagishi Y, Togawa M, Shiomi M (2009) Septic arthritis and acute hematogenous osteomyelitis in childhood at a tertiary hospital in Japan. Pediatr Int 51:371–376

Young TP, Maas L, Thorp AW, Brown L (2011) Etiology of septic arthritis in children: an update for the new millennium. Am J Emerg Med 29:899–902

Gwynne-Jones DP, Stott NS (1999) Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a cause of musculoskeletal sepsis in children. J Pediatr Orthop 19:413–416

Esposito S, Leone S, Bassetti M et al (2009) Italian guidelines for the diagnosis and infectious disease management of osteomyelitis and prosthetic joint infections in adults. Infection 37:478–496

Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG et al (2004) Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis 39:885–910

Falagas ME, Giannopoulou KP, Ntziora F, Papagelopoulos PJ (2007) Daptomycin for treatment of patients with bone and joint infections: a systematic review of the clinical evidence. Int J Antimicrob Agents 30:202–209

Falagas ME, Siempos II, Papagelopoulos PJ, Vardakas KZ (2007) Linezolid for the treatment of adults with bone and joint infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 29:233–239

Falagas ME, Siempos II, Vardakas KZ (2008) Linezolid versus glycopeptide or beta-lactam for treatment of Gram-positive bacterial infections: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis 8:53–66

Falagas ME, Vardakas KZ (2008) Benefit-risk assessment of linezolid for serious gram-positive bacterial infections. Drug Saf 31:753–768

Vardakas KZ, Ntziora F, Falagas ME (2007) Linezolid: effectiveness and safety for approved and off-label indications. Expert Opin Pharmacother 8:2381–2400

Abrahamian FM, Snyder EW (2007) Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: incidence, clinical presentation, and treatment decisions. Curr Infect Dis Rep 9:391–397

Kaplan SL, Hulten KG, Gonzalez BE et al (2005) Three-year surveillance of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections in children. Clin Infect Dis 40:1785–1791

Purcell K, Fergie J (2005) Epidemic of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a 14-year study at Driscoll Children’s Hospital. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 159:980–985

Mantadakis E, Plessa E, Vouloumanou EK, Michailidis L, Chatzimichael A, Falagas ME (2012) Deep venous thrombosis in children with musculoskeletal infections: the clinical evidence. Int J Infect Dis 16:e236–e243

Vardakas KZ, Matthaiou DK, Falagas ME (2009) Comparison of community-acquired pneumonia due to methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus producing the Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 13:1476–1485

Vardakas KZ, Matthaiou DK, Falagas ME (2009) Incidence, characteristics and outcomes of patients with severe community acquired-MRSA pneumonia. Eur Respir J 34:1148–1158

Klein E, Smith DL, Laxminarayan R (2009) Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in outpatients, United States, 1999–2006. Emerg Infect Dis 15:1925–1930

Pichereau S, Rose WE (2010) Invasive community-associated MRSA infections: epidemiology and antimicrobial management. Expert Opin Pharmacother 11:3009–3025

Popovich KJ, Weinstein RA, Hota B (2008) Are community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains replacing traditional nosocomial MRSA strains? Clin Infect Dis 46:787–794

Funding

None

Conflict of interest

None

Ethical approval

Not required

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vardakas, K.Z., Kontopidis, I., Gkegkes, I.D. et al. Incidence, characteristics, and outcomes of patients with bone and joint infections due to community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 32, 711–721 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-012-1807-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-012-1807-3