Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Uterine-sparing procedures are associated with shorter operative time, less blood loss and faster return to activities. Moreover, they are attractive for patients seeking to preserve fertility or concerned about the change of their corporeal image and sexuality after hysterectomy. This study aimed to compare outcomes of transvaginal uterosacral hysteropexy with transvaginal hysterectomy plus uterosacral suspension.

Methods

This retrospective study compared all patients who underwent uterosacral hysteropexy for symptomatic prolapse at our institute to matched control patients who underwent hysterectomy plus uterosacral ligament suspension. Anatomic recurrence was defined as postoperative prolapse stage ≥ II or reoperation for prolapse. Subjective recurrence was defined as the presence of bulging symptoms. PGI-I score was used to evaluate the patients’ satisfaction.

Results

One hundred four patients (52 for each group) were analyzed. Mean follow-up was 35 months. Hysteropexy was associated with shorter operative time and less bleeding compared with hysterectomy (p < 0.0001), without differences in complication rates. Moreover, overall anatomic and subjective cure rate and patient satisfaction were similar between groups. However, hysteropexy was found to be associated with a significantly higher central recurrence rate (21.2% versus 1.9%, p = 0.002), mostly related to cervical elongation, and subsequently a higher reoperation rate (13.5% versus 1.9%, p = 0.04). A 42.9% pregnancy rate in patients still desiring childbirth was found.

Conclusions

Transvaginal uterosacral hysteropexy resulted in similar objective and subjective cure rates, and patient satisfaction, without differences in complication rates, compared with vaginal hysterectomy. However, postoperative cervical elongation may lead to higher central recurrence rates and need for reoperation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a common clinical condition in parous women. Patients may be asymptomatic or bothered by bulging symptoms, urinary incontinence, voiding difficulties, bowel or sexual disorders [1, 2]. POP management includes both conservative interventions and surgical treatment according to prolapse stage, symptoms, general health status and patient preference [3]. Historically, uterine preservation has represented a milestone in POP surgery because of the lower risk of hemorrhagic and infective complications. However, over time hysterectomy became established as the preferred surgical procedure for prolapse repair worldwide [4, 5]. Recently, uterine-sparing procedures have been gaining back popularity with clinicians and patients. Uterus-sparing procedures are associated with shorter operative time, less blood loss and faster return to activities [6]. Moreover, uterine-sparing procedures are attractive not only for patients wanting to preserve fertility but also for women concerned about the change of their body image and sexuality after hysterectomy. However, accurate selection of candidates is needed, and relative contraindications include increased risk of endometrial/cervical/ovarian cancer, uterine abnormalities, post-menopausal bleeding and patients being unable to comply with routine gynecological surveillance [7]. When indicated, hysteropexy can be performed as either a vaginal or abdominal procedure, with or without mesh augmentation. Currently, a gold standard is missing. Despite efficacy, mesh-based surgery has been shown to be associated with complications specific to prosthetic materials. Although over time different strategies have been proposed—including low-weight materials and collagen and stem cell coatings—mesh-related complications are still an issue [8, 9]. Transvaginal native-tissue-based hysteropexy may provide alternative techniques for uterine preservation, without mesh- or trocar-related complications. Transvaginal uterosacral hysteropexy has been shown to be a feasible mesh-free uterine suspension technique with promising results [10]. However, comparative data are lacking. This study aimed to compare transvaginal uterosacral hysteropexy with transvaginal hysterectomy plus uterosacral suspension in terms of operative data, complications, mid-term efficacy and patient satisfaction.

Materials and methods

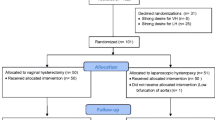

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of San Gerardo Hospital in Monza, Italy. All patients who underwent uterosacral hysteropexy for symptomatic prolapse at our institute from March 2009 to August 2018 were analyzed (group A). Every case was then matched to a control patient who underwent hysterectomy plus uterosacral ligament suspension (group B). A matching procedure was performed for age and preoperative vaginal supports, with blinding to outcomes, using a pre-existing data set.

Preoperative evaluation included a medical interview, clinical examination, urodynamics, pelvic ultrasonography and cervical smear. The presence of bulging symptoms, lower urinary tract symptoms, and sexual and bowel disorders was assessed. Genital prolapse was staged according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system (POP-Q). Women who desired uterus-sparing surgery were counseled about surgical alternative procedures and the lack of long-term outcomes. Patients with a personal history of menopausal uterine bleeding, voluminous uterine fibroids, endometrial hyperplasia or cervical dysplasia were precluded from conservative surgery.

Uterosacral hysteropexy

Patients underwent vaginal hysteropexy through bilateral high uterosacral ligament (USL) suspension according to the previously described technique [11]. Gentle traction was exerted on the cervix to expose the posterior vaginal fornix. A transverse incision of the posterior vaginal fornix was followed by opening of the pouch of Douglas with scissors. The bowel was packed out of the operative field to allow identification of uterosacral ligaments (USLs). Triple transfixion of USLs was performed on each side using double-armed delayed absorbable sutures. The lowest suture was placed at the level of the ischial spinal plane, and the two following were placed 1 cm above each, according to Shull’s technique [12]. To minimize ureteral injury risk, sutures were passed ventral to dorsal [13]. Each dorsal needle was passed posteriorly through the peritoneum and the posterior vaginal wall, encorporating rectovaginal connective tissue, while each ventral needle was passed anteriorly through the peritoneum, the pericervical ring and the vaginal fornix. On each side, the most distal suture was passed laterally, the proximal one medially and the intermediate one between the previous ones. All sutures were tightened to close both the pouch of Douglas and posterior vaginal fornix and suspend the cervix. Additional surgical procedures such as anterior or posterior compartment repair were performed when indicated. Partial trachelectomy was performed only in case of cervical elongation.

Hysterectomy plus uterosacral suspension

After vaginal hysterectomy, the bowel was packed out of the operative field to allow identification of the uterosacral ligaments (USLs). Triple transfixion of USLs was performed on each side using double-armed delayed absorbable sutures. The lowest suture was placed at the level of the ischial spinal plane, and the two following were placed 1 cm above each. Each dorsal needle was passed posteriorly through the peritoneum and the posterior vaginal wall, while each ventral needle was passed anteriorly through the peritoneum and the anterior vaginal wall [14]. On each side, the most distal suture was passed laterally, the proximal one medially and the intermediate one between the previous ones. All sutures were tightened to close and suspend the vaginal cuff. Additional surgical procedures such as anterior or posterior compartment repair were performed when indicated.

Postoperative evaluation

Follow-up visits were scheduled 1, 6 and 12 months after hysteropexy and then annually. Anatomic recurrence was defined as descent of at least one compartment ≥ stage II according to the POP-Q system. Subjective recurrence was defined as the presence of bulging symptoms. Need for POP reoperation was also recorded. Patient Global Impression of Improvement score (PGI-I) was used to evaluate the patients’ satisfaction [15].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP software version 9.0 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). Chi-square test was used for categorical data, Student's t-test for continuous parametrical data and Wilcoxon test for continuous non-parametrical data. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

From hospital records 54 patients who underwent uterosacral hysteropexy were identified. Fifty-two patients completed the minimum 1-year follow-up or relapsed within the first year (group A; 3.7% loss at follow-up). Each patient was matched—with respect to age and preoperative vaginal supports—to a control patient who underwent hysterectomy plus uterosacral ligament suspension (group B; 52 patients). Population characteristics are shown in Table 1. Notably, no differences between groups were noted for the principal risk factors proposed for prolapse surgery failure (age, parity, body mass index and preoperative prolapse severity) [16, 17]. Patients' baseline symptoms were similar between groups. Surgical data are shown in Table 2. Hysteropexy was associated with shorter operative time and less bleeding compared with hysterectomy (p < 0.0001). No differences were observed in terms of associated procedures, such as anterior and posterior compartment repair. Partial trachelectomy was performed in eight (15.4%) women in the hysteropexy group. The complication rate was similar between groups. Specifically, three complications (5.8%) were observed in group A. One patient had urinary tract infection treated with i.v. antibiotics; one patient had a monolateral suburethral sling cut to solve the persistent positive post-voiding residual; one patient had granuloma/suture complex removal in an outpatient setting. In group B, a unilateral ureteral kinking was identified and managed intraoperatively by suture revision. Mean follow-up was 35 months without differences between groups (p = 0.96). Objective and subjective outcomes are shown in Table 3 and in Supplementary Table 1. Anatomic cure rates were 73.1% in group A and 75.0% in group B (p = 0.82). However, while anterior and posterior recurrence was found similar between groups, apical recurrence was significantly higher in the hysteropexy group (21.2% versus 1.9%, p = 0.002). Notably, 9 out of 11 central recurrences (81.8%) in the hysteropexy group were associated with a relevant cervical elongation (mean 6.7 ± 1.5 cm). Moreover, the reoperation rate was significantly higher in the hysteropexy group (13.5% versus 1.9%, p = 0.04). Conversely, subjective recurrence rates and patient satisfaction evaluated with PGI-I were comparable between groups. Table 4 provides the reported functional and pregnancy outcomes. Notably, no differences were found in postoperative symptoms between groups. Three out of seven patients (42.9%) still desiring childbirth became pregnant and delivered at term by elective cesarean section. One patient not desiring childbirth terminated an unwanted pregnancy.

Discussion

The current study was aimed to compare transvaginal uterosacral hysteropexy with transvaginal hysterectomy plus uterosacral suspension in terms of operative data, complications, mid-term efficacy and patient satisfaction. Hysteropexy was associated with shorter operative time and less blood loss, without differences in complication rates. Moreover, objective and subjective cure rates and patient satisfaction results were similar between groups. However, hysteropexy was found to be associated with a significantly higher central recurrence rate, mostly related to cervical elongation, and subsequently a higher reoperation rate.

Uterosacral ligament suspension is a valid procedure for apical repair at the time of hysterectomy and for vaginal vault prolapse surgery [1, 18, 19]. Encouraging data have also been reported for uterosacral ligament uterine suspension [10]. However, to date there are few comparison studies on uterosacral hysteropexy; most describe the abdominal route. Rosen et al. compared laparoscopic total hysterectomy with laparoscopic uterosacral hysteropexy and found the latter to be associated with shorter operative time and less blood loss, without differences in complications [20]. Our surgical data supported these findings and confirmed that avoiding hysterectomy leads to a clear advantage in terms of operative time and bleeding without downsides concerning complications. Similar complication rates were also reported by two other studies comparing vaginal hysterectomy with either laparoscopic uterosacral hysteropexy or vaginal uterosacral hysteropexy [21, 22].

Our study showed uterosacral hysteropexy to have similar patient satisfaction rates and overall anatomic and subjective cure rates compared with hysterectomy. These findings are supported by all other available studies [20,21,22]. Haj-Yahya et al. found similar objective, subjective and patient satisfaction at short-term follow-up comparing laparoscopic uterosacral hysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy [21]. Similarly, Rosen et al. demonstrated equal outcomes when comparing laparoscopic hysterectomy to laparoscopic uterosacral hysteropexy [20]. Also, Romanzi et al. found similar anatomic outcomes evaluated with the half-way system at 1.5 years between vaginal hysterectomy and vaginal uterosacral hysteropexy, but subjective outcomes were not evaluated [22]. However, when we analyzed anatomic recurrence by compartment, we found a significantly higher rate of apical recurrence (21.2% versus 1.9%, p = 0.002), and this was related to severe cervical elongation in 81.8% of cases. This is not unexpected, since it is described as the main pitfall of conservative surgery and reported in up to 62.5% of patients [23]. Specifically, Rosen et al. found 14% of cervical elongation after laparoscopic uterosacral hysteropexy, which can potentially require further surgery [20]. Indeed, in our study, cervical elongation led to a significantly higher reoperation rate in the hysteropexy group (13.5% versus 1.9%, p = 0.04), even though we performed partial trachelectomy in case of preoperative cervical hypertrophy. This value is in the range of a 0–29% reintervention rate for recurrence reported by Meriwether et al. in a recent systematic review [24]. It might be speculated that a 15.4% trachelectomy rate is too low to successfully bring down the risk of postoperative cervical elongation, which still represents the main issue. Specifically, in our study, all but one patient with postoperative cervical elongation did not receive partial trachelectomy at the time of primary surgery. Probably the indication for this additional procedure should be extended to a greater proportion of patients undergoing hysteropexy.

Lastly, in our series, we registered an encouraging 42.9% pregnancy rate, although the population is small for reaching conclusions. This finding is difficult to compare with other studies since data regarding pregnancy following hysteropexy are scarce in the literature. As a result, a very limited amount of information is available for counseling women desiring childbirth [25].

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing transvaginal uterosacral hysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy plus uterosacral suspension in multimodal modes, including the POP-Q-based anatomic cure rate, subjective cure rate, functional outcomes and patient satisfaction. Other strengths include adequate population balancing for the main recurrence risk factors, mid-term follow-up and pregnancy data analysis. Limitations include the retrospective study design and small sample size. More studies are needed to define the role of uterine-sparing techniques for prolapse repair.

Conclusions

Transvaginal uterosacral hysteropexy resulted in similar objective and subjective cure rates, and patient satisfaction, without differences in complication rates, compared with vaginal hysterectomy. However, postoperative cervical elongation may lead to higher central recurrence rates and need for reoperation. This technique can be indicated as a uterine-sparing surgical option without the use of prosthetic material.

References

Milani R, Frigerio M, Cola A, Beretta C, Spelzini F, Manodoro S. Outcomes of transvaginal high uterosacral ligaments suspension: over 500-patient single-Center study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24(1):39–42.

Frigerio M, Manodoro S, Cola A, Palmieri S, Spelzini F, Milani R. Detrusor underactivity in pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(8):1111–6.

Palmieri S, Cola A, Milani R, Manodoro S, Frigerio M. Quality of life in women with advanced pelvic organ prolapse treated with Gellhorn pessary. Minerva Ginecol. 2018;70(4):490–2.

Jha S, Moran P. The UK national prolapse survey: 5 years on. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(5):517–28.

Vanspauwen R, Seman E, Dwyer P. Survey of current management of prolapse in Australia and New Zealand. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):262–7.

Ridgeway BM. Does prolapse equal hysterectomy? The role of uterine conservation in women with uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):802–9.

Gutman RE. Does the uterus need to be removed to correct uterovaginal prolapse? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;28(5):435–40.

Lo TS, Cortes EFM, Wu PY, Tan YL, Al-Kharabsheh A, Pue LB. Assessment of collagen versus non collagen coated anterior vaginal mesh in pelvic reconstructive surgery: prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;198:138–44.

Spelzini F, Manodoro S, Frigerio M, Nicolini G, Maggioni D, Donzelli E, et al. Stem cell augmented mesh materials: an in vitro and in vivo study. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(5):675–83.

Milani R, Frigerio M, Manodoro S, Cola A, Spelzini F. Transvaginal uterosacral ligament hysteropexy: a retrospective feasibility study. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(1):73–6.

Milani R, Frigerio M, Spelzini F, Manodoro S. Transvaginal uterosacral ligament hysteropexy: a video tutorial. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(5):789–91.

Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1365–73 discussion 1373-4.

Manodoro S, Frigerio M, Milani R, Spelzini F. Tips and tricks for uterosacral ligament suspension: how to avoid ureteral injury. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(1):161–3.

Spelzini F, Frigerio M, Manodoro S, Interdonato ML, Cesana MC, Verri D, et al. Modified McCall culdoplasty versus Shull suspension in pelvic prolapse primary repair: a retrospective study. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(1):65–71.

Srikrishna S, Robinson D, Cardozo L. Validation of the patient global impression of improvement (PGI-I) for urogenital prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(5):523–8.

Manodoro S, Spelzini F, Cesana MC, Frigerio M, Maggioni D, Ceresa C, et al. Histologic and metabolic assessment in a cohort of patients with genital prolapse: preoperative stage and recurrence investigations. Minerva Ginecol. 2017;69(3):233–8.

Manodoro S, Frigerio M, Cola A, Spelzini F, Milani R. Risk factors for recurrence after hysterectomy plus native-tissue repair as primary treatment for genital prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(1):145–51.

Milani R, Frigerio M, Spelzini F, Manodoro S. Transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension for posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(9):1421–3.

Milani R, Frigerio M, Vellucci FL, Palmieri S, Spelzini F, Manodoro S. Transvaginal native-tissue repair of vaginal vault prolapse. Minerva Ginecol. 2018;70(4):371–7.

Rosen DM, Shukla A, Cario GM, Carlton MA, Chou D. Is hysterectomy necessary for laparoscopic pelvic floor repair? A prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(6):729–34.

Haj-Yahya R, Chill HH, Levin G, Reuveni-Salzman A, Shveiky D. Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament hysteropexy vs total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension for anterior and apical prolapse: surgical outcome and patient satisfaction. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019.

Romanzi LJ, Tyagi R. Hysteropexy compared to hysterectomy for uterine prolapse surgery: does durability differ? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(5):625–31.

Hyakutake MT, Cundiff GW, Geoffrion R. Cervical elongation following sacrospinous hysteropexy: a case series. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(6):851–4.

Meriwether KV, Balk EM, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, Kim-Fine S, Murphy M, et al. Uterine-preserving surgeries for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(4):505–22.

Gutman R, Maher C. Uterine-preserving POP surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(11):1803–13.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R Milani: Project development, surgery.

A Cola: Project development, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing.

N Bellante: Project development, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing.

S Palmieri: Project development, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing.

S Manodoro: Project development, surgery, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing.

F Spelzini: Project development, surgery.

M Frigerio: Project development, surgery, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOC 32.5 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Milani, R., Manodoro, S., Cola, A. et al. Transvaginal uterosacral ligament hysteropexy versus hysterectomy plus uterosacral ligament suspension: a matched cohort study. Int Urogynecol J 31, 1867–1872 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04206-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04206-2