Abstract

Purpose of review

Musculoskeletal disorders are a leading contributor to healthcare resource use and reduced quality of life, particularly in osteoarthritis of the hip/knee. Consequently, the volume of arthroplasty procedures continues to rise and there is a critical need to identify interventions that provide value-based care. Economic evaluations that assess both cost and health outcomes simultaneously allow clinicians and policymakers to make informed decisions regarding cost-effective interventions. The purpose of this review was to summarize and evaluate the methodological quality of economic evaluations of hip/knee interventions in arthroplasty.

Recent findings

We identified 384 studies. Two-thirds did not meet the criteria for full economic evaluations (compared costs independently). Several studies (28%) inappropriately concluded interventions were cost-effective. Using a validated quality assessment tool, we determined the quality of full economic evaluations in hip/knee arthroplasty is generally good; however, important areas for quality improvement are related to reporting perspective, costing methodology, and funding.

Summary

Value-based care in arthroplasty relies on the quality of the literature. Although the quality is generally good, few full economic evaluations are published in arthroplasty. Yet, these are necessary to appropriately infer intervention cost-effectiveness. Unfortunately, clinical decisions continue to be made using highly cited low-quality or partial economic evaluations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The burden of musculoskeletal disorders is substantial, contributing heavily to worldwide disability [1, 2] and healthcare costs [3, 4]. After lower back and neck pain, osteoarthritis (OA) is the next leading cause of the burden for MSK disorders and the 11th highest contributor to the global burden of disability worldwide [5]. The hip and knee are the most commonly affected joints, with arthroplasty (i.e., surgical reconstruction or replacement of the joint) often recommended as a primary treatment for the OA patient population. Hundreds of thousands of arthroplasty procedures are performed annually [6] and the volume continues to rise with an estimated increase of > 70% for hip arthroplasty and > 80% for knee arthroplasty over the next 5 to 10 years [7,8,9]. In Australia, arthroplasty utilization is expected to grow by approximately 250% by 2030, leading to more than 8 billion dollars in healthcare costs for Australia alone [10]. It is essential to identify ways to minimize healthcare spending for arthroplasty treatments while providing optimal value-based care for patients.

Research methodologies that include economic evaluation allow comparison of cost and health outcomes simultaneously between different treatments and can help policymakers make informed decisions on the distribution of scarce healthcare resources [11]. Accordingly, guidelines have been established internationally for conducting economic evaluations [12, 13]. Given the substantial volume of arthroplasty procedures performed globally, it is important to evaluate the overall quality of the economic evaluations in the arthroplasty literature.

The quality of economic evaluations in arthroplasty has previously been studied through systematic reviews [14, 15, 16••]. Overall, study quality has been reported as good. However, despite the rich volume of available arthroplasty literature, previous reviews have only summarized small samples of studies (i.e., n < 25) due to restrictive eligibility criteria including the exclusion of studies that evaluate pre- or post-surgical treatment, prophylaxis treatment, or non-elective arthroplasty (e.g., to treat hip fracture) and the exclusion of studies that were not conducted in the United States (US). All three reviews focus on full economic evaluations only and the most recent review only included studies up until 2016. Given the recent changes in the delivery of care with emphasis on outpatient arthroplasty and comparisons of arthroplasty to non-surgical interventions, an updated review is warranted. We also believe it is important to systematically evaluate arthroplasty economic evaluations globally and to include all components of arthroplasty interventions to get a more comprehensive assessment of economic evaluations in the field, including studies that evaluate cost independently.

To meet the criteria of a full economic evaluation, a study must compare two or more treatment alternatives and include both health benefits and costs in the outcome analysis [11]. A full economic evaluation is crucial for decision-makers to make an appropriate assessment of the cost-effectiveness of an intervention. Partial economic evaluations compare costs independently from health outcomes and therefore do not meet the necessary criteria. To date, no study has evaluated the quality of all forms of economic evaluation globally for arthroplasty interventions of the hip and/or knee.

Therefore, the aims of our study were as follows (1) to summarize and evaluate the reporting of economic evaluations in the arthroplasty literature for hip and knee interventions; (2) to evaluate the quality of published full economic evaluations and; (3) to identify important areas where study quality can be improved.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

We completed a systematic search of the literature from inception to March 1, 2020, using four databases (Medline, EMBASE, AMED, and OVID Health Star). We identified articles published in the English language using combined and/or truncated terms that included economic, economic evaluation, cost, cost-utility, cost-minimization, cost-effectiveness, or cost-benefit as well as hip, or knee. We included studies that met the following three criteria: (1) evaluated hip and/or knee arthroplasty interventions; (2) compared two or more interventions and; (3) reported a cost outcome. We included studies that evaluated a variety of areas in arthroplasty including comparisons of different surgical techniques and/or implants, pre- or post-operative rehabilitation techniques, anesthetics and/or medications, intraoperative tools/equipment, and surgical to non-surgical interventions.

Abstract and full-text screening

Three reviewer pairs independently screened titles and abstracts to establish whether each study met the eligibility criteria to be included for a full-text review. We excluded study protocols, conference abstracts, and duplicates. For abstracts that met the criteria (or those where one or both of the reviewers were uncertain of eligibility), we retrieved the full article and further evaluated whether studies fully met the eligibility criteria. We manually searched the reference lists of systematic reviews and meta-analyses pulled from the initial search strategy to identify any other relevant studies that met the criteria. Four independent reviewer pairs then screened the full-text articles for eligibility. Reviewer pairs extracted data from full texts of eligible studies and once completed, met to discuss the data and resolve any conflicts. We asked a third reviewer to help resolve conflicts for articles where the reviewer pair could not reach consensus.

Data abstraction

We used a custom data abstraction form to extract several variables from the full texts including the following:

-

Year of publication

-

Country of origin

-

Interventions studied

-

Type of economic evaluation (i.e., cost-minimization analysis, cost-utility analysis, cost-benefit analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost analysis, or more than one)

-

Study design (i.e., model- or trial-based)

-

Trial design for trial-based studies (i.e., randomized controlled trial, prospective, retrospective) or model design for model-based studies (i.e., Markov model, decision tree, or decision tree and Markov)

-

Summary measure reported (i.e., mean difference, incremental net benefit [INB], incremental cost-effectiveness, or cost-utility ratios [ICER & ICUR])

-

Uncertainty reported

-

Sensitivity analyses completed

-

Perspective of the analysis

Quality assessment

We used the Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) tool (Supplemental Table 1) [17, 18] to evaluate the quality of full economic evaluations. The QHES is a valid and reliable tool that uses 16 questions (binary, yes or no) to assess whether studies report the fundamental components required for an economic evaluation of high quality. The questions are scored from 1 to 9 points [17, 18], where a “yes” answer receives all points for the given question and a “no” answer receives no points. The individual question scores are then tallied to obtain a final summary score (0 to 100) with higher scores indicating better overall study quality.

We established clearly defined criteria for each of the QHES questions at the beginning of the study, made available for all reviewers. As recommended by previous studies [19], we had the same four reviewer pairs independently complete the quality assessments. In addition to the conventional QHES standards, we used the detailed criteria established by Marshall et al. [20] to supplement question scoring. We also used the criteria from Supplemental Table 2 to further clarify questions. We pilot tested with the assessment of five studies at random prior to completing all QHES scoring to ensure consistent interpretation of questions among reviewers. After completing all of the quality assessments, each reviewer pair met to discuss the data and resolve any conflicts. We asked a third reviewer to help resolve conflicts for articles where the reviewer pair could not reach consensus.

Inter-rater agreement

We used Cohen’s Kappa statistic to evaluate agreement for abstract screening between each of the three reviewer pairs. Kappa statistic values can be interpreted as almost perfect agreement (0.81–0.99), substantial agreement (0.61–0.80), moderate agreement (0.41–0.60), fair agreement (0.21–0.40), or slight agreement (0.01–0.20) [21]. We also evaluated agreement for each of the 16 QHES questions among each of the four full-text reviewer pairs. This was done by calculating the percentage of agreements observed (i.e., both said yes or both said no).

Descriptive analyses

We summarized our results using descriptive analyses. We reported the frequency (percentage [%]) of studies by year of publication and design characteristics and interventions studied. We reported the mean quality score (standard deviation [SD]) of the QHES for all studies, by year of publication, by intervention and by geographical location. Finally, we reported the frequency (%) of studies that addressed each of the 16 QHES questions. We also categorized studies for overall quality by quartile using the final QHES scores [22]. The quartiles are classified as high quality (75–100 points), fair quality (50–74 points), poor quality (25–49 points), or extremely poor quality (0–24 points).

Results

Studies summary

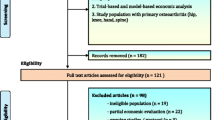

A total of 477 studies met the eligibility criteria following the initial titles and abstracts screening. After reviewing full texts, we determined 107 studies did not fully meet the criteria and were excluded. Fourteen additional articles that met inclusion criteria were identified through systematic reviews. A total of 384 [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,260,261,262,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313,314,315,316,317,318,319,320,321,322,323,324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331,332,333,334,335,336,337,338,339,340,341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348,349,350,351,352,353,354,355,356,357,358,359,360,361,362,363,364,365,366,367,368,369,370,371,372,373,374,375,376,377,378,379,380,381,382,383,384,385,386,387,388,389,390,391,392,393,394,395,396,397,398,399,400,401,402,403,404,405] studies were ultimately included in the systematic review (Fig. 1).

Table 1 summarizes all of the included studies (n = 384). The table also provides a summary of studies that specifically completed a full economic evaluation (n = 127). Interestingly, several studies (n = 72; 28%) that did not carry out a full economic evaluation (i.e., cost analyses—only costs compared directly) drew conclusions concerning cost-effectiveness. Overall, the frequency of studies published increased over time between the years of 1980 and 2020 (Fig. 2). Although the number of partial economic evaluations continued to rise over the years, the number of published full economic evaluations peaked between 2010 and 2014 (Fig. 2). Individual summaries for each study are presented in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4.

Studies most frequently evaluated surgical techniques/implants (n = 120; 31%) or anesthetics/medications (n = 117; 30%). Studies also evaluated pre- or post-operative rehabilitation techniques (n = 59; 15%), intraoperative tools and/or equipment (n = 65; 17%), or compared surgical interventions to non-surgical interventions (n = 23; 6%).

Inter-rater agreement

For the titles and abstracts screening, inter-rater agreement was strong. Cohen’s Kappa statistics indicated substantial (0.61 to 0.80) to almost perfect (0.81 to 0.99) agreement between each of the three reviewer pairs (0.81, 0.76 and 0.63) [21].

For the quality assessment, the average inter-rater agreement across all 16 questions was also strong for each of the four reviewer pairs (95%, 89%, 89%, and 88%). Agreement was particularly strong for 11 of the 16 questions of the QHES (Q1, Q3–9, Q13 and Q15–16) with agreement exceeding 80% in all four pairings (Supplemental Table 5).

Quality assessment

We assessed the quality of 127 full economic evaluations. The mean QHES was 83.5 (SD = 17.8). According to Spiegel et al.’s [22] quartiles, 96 studies (76%) were considered high quality, while fewer studies were considered fair (n = 22; 17%) and poor (n = 9; 7%) (Supplemental Fig. 1). The overall quality of studies did not show a trend over time (Fig. 3).

Studies conducted in North America, the UK or Europe were generally considered of high quality, while the pooled estimate of the remaining countries was considered fair overall (Table 2). Most full economic evaluations compared surgical techniques/implants or anesthetics/medications and the mean quality of these study types was high (Table 2). The mean study quality was also high for studies that compared pre- or post-operative rehabilitation techniques and those that compared surgical interventions to non-surgical interventions (Table 2), despite a smaller volume of published studies. Studies that evaluated intraoperative tools and/or equipment were considered fair quality (Table 2) with a smaller volume of published studies as well.

QHES questions

Thirteen of the 16 QHES tool questions were addressed frequently (i.e. over 80% of the time) across all full economic evaluations: Q1, Q3–8, and Q10–15 (Fig. 4). Questions that were addressed less frequently were related to whether authors appropriately stated and justified the costing perspective (Q2), reported costing methodology (Q9), and whether a funding statement was provided (Q16).

Discussion

We summarized data from 384 economic evaluations that assessed arthroplasty interventions of the hip and/or knee. According to international health economic guidelines, clinical and policy decision-making should be made based on evidence that evaluates the cost and effect of treatment alternatives simultaneously (i.e., full economic evaluations) [12, 13]. Although there was a large volume of studies identified in our review, approximately two thirds (67%) did not complete a full economic evaluation. Many of these studies (n = 72; 28%) also made conclusions regarding the cost-effectiveness of interventions despite not conducting a full economic evaluation. This is particularly concerning as several of these studies are highly cited. For example, one study (cited 245 times) concluded that tranexamic acid was a cost-effective intervention compared to placebo; however, cost and health outcomes were evaluated independently [193]. To avoid potential confusion and misinterpretation of study findings for readers, authors should be mindful of the use of similar terms in studies. There was an increasing trend in the number of partial economic evaluations published over the years, while the number of published full economic evaluations peaked between 2010 and 2014. Our results, therefore, highlight the dire need for more full economic evaluations of high quality in the field arthroplasty to assist with informed policy decision-making.

Nevertheless, evaluation of the identified full economic evaluations (n = 127) showed that overall, studies were typically considered high quality (76%). Over the last 3 years, several studies have even scored a perfect 100 on the QHES [36••, 134••, 141••, 398••] and provide great examples for researchers to reference when designing studies and drafting manuscripts or for critical appraisal of studies. Few studies were considered fair quality (17%) or poor quality (7%) [22]. The overall mean QHES score was 83.5 ± 18 with no observable trend in study quality over time (Fig. 3). Although the volume of published studies is small, these results are encouraging for the future of health economic research in arthroplasty. Studies conducted in North America, the UK, and European countries accounted for 92% of studies and generally scored high on the QHES (Table 2), suggesting economic evaluation methodologies are likely well-established in these countries. Comparatively, studies conducted in other countries were considered fair, on average (Table 2). When evaluating quality by intervention type, studies that evaluated anesthetics and/or medications, pre- or post-operative rehabilitation, or that compared surgical to non-surgical treatment scored very well on the QHES. The lowest scores were shown in studies evaluating surgical techniques/implants, as well as studies evaluating intraoperative tools and equipment. These results highlight the importance of ensuring arthroplasty surgeons follow international guidelines for reporting economic evaluations to help improve the overall quality of studies in these areas.

Previous systematic reviews evaluating full economic evaluations for arthroplasty interventions have also reported good overall study quality. Daigle et al. [14] reported a mean study quality of 5.8 out 7 (n = 13) using a self-designed scoring tool. Nwachukwu et al. [16••] reported a mean study quality of 86.4 (range, 63–100; n = 23) in US-based studies while also using the QHES tool. Although not the primary goal of their paper, Kamaruzaman et al. [15•] reported individual QHES scores for their review (n = 23) and concluded study quality to be moderate overall. However, there are important differences between the previous reviews and the present study. We included studies globally which enabled a much larger study sample of full economic evaluations to be included (n = 127). We also assessed all components related to arthroplasty intervention such as prophylaxis, pre- or post-operative rehabilitation and intraoperative tools and equipment. Importantly, we evaluated both full and partial economic evaluations to get a more comprehensive understanding of the arthroplasty literature and potential pitfalls for readers in the interpretation of study results. When compared with other fields of health, the quality of full economic evaluations in the field of arthroplasty is high (i.e., QHES ≥ 75). Studies evaluating ischemic heart disease [406], and physical therapy [407] have also reported overall good study quality, while other fields of health have reported poor to fair (QHES = 25 to 74) study quality including the literature for digestive diseases [22], nursing [20], and oncology [408].

Through the QHES tool, we were able to identify important areas to improve overall study quality in the arthroplasty literature. Although 13 of the 16 QHES questions were appropriately addressed by studies, Q2, Q9, and Q16 were addressed less frequently (Fig. 4). The most problematic QHES question was Q2 which addresses whether a study states and justifies the costing perspective of the analysis. A mere 65% of studies addressed the question in this review. Transparency of the costing perspective is crucial to ensure that all of the necessary costs are being included in the analysis for answering the given question. Moreover, Primeau et al. [409] showed the cost-effectiveness of treatments can be dependent on the perspective analyzed. Their results showed that evaluating from a healthcare payer perspective (includes direct costs chargeable to the public payer) compared to a societal perspective (includes direct costs and indirect costs such as time away from work) provided contradictory results on treatment cost-effectiveness. Therefore, the perspective of the analysis is incredibly important for the appropriate interpretation of the study results in making health policy decisions. Guidelines now recommend that economic evaluations be conducted from multiple perspectives (e.g., healthcare payer and societal) to broaden the interpretability of study results. Interestingly, only 10 of the 127 included studies (8%) evaluated their data from multiple perspectives. Many studies evaluated their data from a hospital perspective (i.e., surgical and inpatient costs), which is considered a narrower viewpoint when compared with other perspectives.

The other two questions that were less frequently addressed related to whether appropriate costing methodology was used (Q9) and whether a funding statement was provided (Q16). Authors should be transparent in the reporting of costing sources and providing specific unit costs as costs can be quite variable from one healthcare system to another (e.g., private vs. public systems). Funding statements are also important for disclosing any conflicts of interest that could potentially bias the results of the study. For example, it is important to consider the funding source of a study that concludes a knee implant is cost-effective when it was funded by the manufacturer of the implant. On another note, although most studies scored well on Q5 (87%) which addresses whether authors handled uncertainty, we awarded points for the question if the study either (1) accounted for uncertainty through the use of bootstrapping, cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, cost-effectiveness planes, and/or 95% confidence intervals or (2) if authors performed sensitivity analyses to cover a range assumption. Most studies completed sensitivity analyses (88%); however, 55 of the 129 studies (43%) did not account for statistical uncertainty (Table 1). All possible levels of uncertainty should be accounted for in a full economic evaluation. As a general recommendation, investigators should follow guidelines for conducting economic evaluations when designing studies [12, 13] to improve study quality. It may be more difficult for reviewers to use full guidelines when critically appraising studies; however, the use of more user-friendly tools such as the QHES is highly encouraged.

Lastly, average cost-effectiveness ratios (ACER) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) are often used interchangeably in economic evaluations. Although both provide summary measures of the relationship between cost and effect, they answer very different questions. The important difference between the two is the ACER provides an overall estimate for each treatment (ACER = Cost/Effect), while the ICER provides an incremental estimate between treatments (i.e., ICER = ΔCost/ΔEffect). The ACER summary measure can be misleading as it distributes the difference in cost across all participants and assumes all health effects are produced at an equivalent cost [410]. Current guidelines recommend the use of the ICER as the summary measure [12, 13]. However, 11 of the 127 studies (9%) in this review reported the ACER in their study results while making inferences on cost-effectiveness. Another problematic finding is that very few studies (n = 12, 9%, full economic evaluations; n = 23, 6%, all studies overall) compared surgical to non-surgical interventions and even fewer included indirect costs in their analysis. It is particularly important to complete full economic evaluations that consider the impact of both direct (e.g., procedure and treatment costs) and indirect costs (e.g., loss in productivity or time away from work) to compare surgical and non-surgical interventions to make informed clinical decisions concerning cost-effectiveness.

Indeed, there are limitations to the present study. First, the QHES tool evaluates internal validity, not the generalizability of results (i.e., external validity). Therefore, studies that score well on the QHES may not necessarily provide study results that are clinically relevant or applicable. Policy decision-makers will also need to take this into consideration when assessing studies. Second, there are some restrictions associated with using the QHES tool to assess quality. There is a possibility that studies with great research methodology could have lost points for questions if the explanations that were provided lacked clarity or if specific information was omitted. Finally, there is a degree of subjectivity with using the QHES tool for quality scoring. To account for this, we had reviewer pairs follow additional criteria established by Marshall et al. [20] to supplement their scoring of the QHES and we also provided further clarifications to the question criteria (Supplemental Table 2). Additionally, we had all reviewers pilot test five studies with the QHES tool prior to evaluating all of the included articles to ensure measurement consistency among reviewer pairs. Accordingly, we showed excellent inter-rater agreement in our assessment of study quality (Supplemental Table 5).

Optimization of value-based care and healthcare resource allocation for hip and knee arthroplasty depends heavily on the quality of available literature. Generally, arthroplasty study quality is high; however, the volume of published full economic evaluations is still quite small when compared to studies that evaluate cost independently. Full economic evaluations are required to infer appropriate conclusions concerning cost-effectiveness, yet only 33% of studies from this review met the necessary criteria. There is a dire need for more full economic evaluations in the field of arthroplasty. Research consumers also need to be aware of common pitfalls in the literature including the inappropriate use of the term “cost-effective” in partial economic evaluations as several studies have been cited over 100 times. When designing studies, investigators need to prioritize strong research methodology and follow available criteria to improve study design and quality including guidelines for economic evaluation (e.g., Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine) or scoring instruments such as the QHES tool.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Briggs AM, Cross MJ, Hoy DG, Sanchez-Riera L, Blyth FM, Woolf AD, et al. Musculoskeletal health conditions represent a global threat to healthy aging: a report for the 2015 World Health Organization world report on ageing and health. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 2):S243–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw002.

Vos T, Allan C, Arora M, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet (London, England). 2016;388(10053):1545–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31678-6.

Dieleman JL, Cao J, Chapin A, Chen C, Li Z, Liu A, et al. US health care spending by payer and health condition, 1996-2016. JAMA. 2020;323(9):863–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.0734.

Losina E, Dervan EE, Paltiel AD, Dong Y, Wright RJ, Spindler KP, et al. Defining the value of future research to identify the preferred treatment of meniscal tear in the presence of knee osteoarthritis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130256. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130256.

Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323–30. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763.

Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Widmer M, Maravic M, Gómez-Barrena E, et al. International survey of primary and revision total knee replacement. Int Orthop. 2011;35(12):1783–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-011-1235-5.

Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991-2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227–36. https://doi.org/10.1001/2012.jama.11153.

Hooper G, Lee AJ, Rothwell A, Frampton C. Current trends and projections in the utilisation rates of hip and knee replacement in New Zealand from 2001 to 2026. N Z Med J. 2014;127(1401):82–93.

Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(17):1455–60. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.17.01617.

Ackerman IN, Bohensky MA, Zomer E, Tacey M, Gorelik A, Brand CA, et al. The projected burden of primary total knee and hip replacement for osteoarthritis in Australia to the year 2030. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2411-9.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies: Canada. In: CADTH. Ottawa: 2017 Mar.

Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, Brock DW, Feeny D, Krahn M, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093–103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.12195.

Daigle ME, Weinstein AM, Katz JN, Losina E. The cost-effectiveness of total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review of published literature. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26(5):649–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2012.07.013.

Kamaruzaman H, Kinghorn P, Oppong R. Cost-effectiveness of surgical interventions for the management of osteoarthritis: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1540-2. A systematic review summarizing full economic evaluations in the surgical arthroplasty literature. Although there is no summary score for all studies using the Quality of Health Economics Studies (QHES) tool, individual QHES scores are provided for each study.

Nwachukwu BU, Bozic KJ, Schairer WW, Bernstein JL, Jevsevar DS, Marx RG, et al. Current status of cost utility analyses in total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5):1815–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3964-4. A systematic review reporting the quality of cost-utility analyses for surgical arthroplasty interventions (excluding prophylaxis, rehabilitation, etc.) in the United States alone. The study reports a mean study quality of 86.4 on the Quality of Health Economics Studies (QHES) tool.

Chiou CF, Hay JW, Wallace JF, Bloom BS, Neumann PJ, Sullivan SD, et al. Development and validation of a grading system for the quality of cost-effectiveness studies. Med Care. 2003;41(1):32–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200301000-00007.

Ofman JJ, Sullivan SD, Neumann PJ, Chiou CF, Henning JM, Wade SW, et al. Examining the value and quality of health economic analyses: implications of utilizing the QHES. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9(1):53–61. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.1.53.

Gerkens S, Crott R, Cleemput I, Thissen JP, Closon MC, Horsmans Y, et al. Comparison of three instruments assessing the quality of economic evaluations: a practical exercise on economic evaluations of the surgical treatment of obesity. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2008;24(3):318–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266462308080422.

Marshall DA, Donald F, Lacny S, Reid K, Bryant-Lukosius D, Carter N, et al. Assessing the quality of economic evaluations of clinical nurse specialists and nurse practitioners: a systematic review of cost-effectiveness. Nurs Plus Open. 2015;1:11–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2015.07.001.

Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):360–3.

Spiegel BM, Targownik LE, Kanwal F, Derosa V, Dulai GS, Gralnek IM, et al. The quality of published health economic analyses in digestive diseases: a systematic review and quantitative appraisal. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(2):403–11. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.020.

Abdel MP, Miller LE, Hanssen AD, Pagnano MW. Cost analysis of dual-mobility versus large femoral head constructs in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2019;34(2):260–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.09.085.

Abdool-Carrim T, Adler H, Becker P, Carides M, Ginsberg J, Golele R, et al. The cost and benefit of prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis in elective hip replacement. DVT/PE prophylaxis consensus forum. S Afr Med J. 1997;87(5):594–600.

Adeyemi A, Trueman P. Economic burden of surgical site infections within the episode of care following joint replacement. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1):196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-019-1224-8.

Agarwal N, Rao N, Mekheil M, Tancredi N, Oken J. Safety, efficacy and cost analysis of Rivaroxaban versus Fondaparinux for thromboprophylaxis after joint replacement at an inpatient rehabilitation facility. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2015;3:538–43. https://doi.org/10.17265/2328-2150/2015.11.006.

Akindolire J, Morcos MW, Marsh JD, Howard JL, Lanting BA, Vasarhelyi EM. The economic impact of periprosthetic infection in total hip arthroplasty. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E52-e6. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.004219.

Allen LR, Bonck MJ, Lofgren KL, Mayo KW, Mozaffari E. Low-molecular-weight heparin therapy for patients undergoing total knee replacement surgery: cost and outcomes. Hosp Pharm. 2003;38(9):833–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/001857870303800908.

Alshryda S, Mason J, Sarda P, Nargol A, Cooke N, Ahmad H, et al. Topical (intra-articular) tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates following total hip replacement: a randomized controlled trial (TRANX-H). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1969–74. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.L.00908.

Andreasen SE, Holm HB, Jorgensen M, Gromov K, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Husted H. Time-driven activity-based cost of fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(6):1747–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.12.040.

Arana M, Harper L, Qin H, Mabrey J. Reducing length of stay, direct cost, and readmissions in total joint arthroplasty patients with an outcomes manager-led interprofessional team. Orthop Nurs. 2017;36(4):279–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/nor.0000000000000366.

Arterburn D, Wellman R, Westbrook E, Rutter C, Ross T, McCulloch D, et al. Introducing decision aids at group health was linked to sharply lower hip and knee surgery rates and costs. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2012;31(9):2094–104. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0686.

Asche CV, Ren J, Kim M, Gordon K, McWhirter M, Kirkness CS, et al. Local infiltration for postsurgical analgesia following total hip arthroplasty: a comparison of liposomal bupivacaine to traditional bupivacaine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(7):1283–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2017.1314262.

Ast MP, Mayman DJ, Su EP, Gonzalez Della Valle AM, Parks ML, Haas SB. The reduction of implant-related errors and waste in total knee arthroplasty using a novel, computer based, label and compatibility system. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(1):132–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.03.013.

Aydin BK, Durgut F, Erkocak OF, Acar MA. Other benefits of intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid in primary total knee arthroplasty apart from reducing blood transfusion rates. Joint Dis Relat Surg. 2017;28(1):25–9. https://doi.org/10.5606/ehc.2017.52725.

Barlow BT, McLawhorn AS, Westrich GH. The cost-effectiveness of dual mobility implants for primary total hip arthroplasty: a computer-based cost-utility model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(9):768–77. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.16.00109.A full economic evaluation of a Markov model comparing dual-mobility to conventional implants in total hip arthroplasty that scored a perfect 100 on the Quality of Health Economics Studies (QHES) tool. The paper provides a great reference for researchers when designing studies and drafting manuscripts or for critical appraisal of studies.

Barrack RL. The economics of revision arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 1995;18(9):874–5.

Barrack RL. Economics of the infected total knee replacement. Orthopedics. 1996;19(9):780–2.

Barrack RL. The evolving cost spectrum of revision hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 1999;22(9):865–6.

Barrack RL, Castro F, Guinn S. Cost of implanting a cemented versus cementless femoral stem. J Arthroplast. 1996;11(4):373–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0883-5403(96)80025-8.

Barrack RL, Hoffman GJ, Tejeiro WV, Carpenter LJ Jr. Surgeon work input and risk in primary versus revision total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 1995;10(3):281–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0883-5403(05)80175-5.

Barrack RL, Ruh EL, Williams BM, Ford AD, Foreman K, Nunley RM. Patient specific cutting blocks are currently of no proven value. J Bone Joint Surg Br Vol. 2012;94(11 Suppl A):95–9. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.94b11.30834.

Batsis JA, Naessens JM, Keegan MT, Huddleston PM, Wagie AE, Huddleston JM. Resource utilization of total knee arthroplasty patients cared for on specialty orthopedic surgery units. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(3):218–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.299.

Baxter K, Bevan G. An economic model to estimate the relative costs over 20 years of different hip prostheses. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(9):542–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.53.9.542.

Beard DJ, Davies LJ, Cook JA, MacLennan G, Price A, Kent S, et al. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of total versus partial knee replacement in patients with medial compartment osteoarthritis (TOPKAT): 5-year outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2019;394(10200):746–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31281-4.

Bedair H, Cha TD, Hansen VJ. Economic benefit to society at large of total knee arthroplasty in younger patients: a Markov analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(2):119–26. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.L.01736.

Bedair H, Yang J, Dwyer MK, McCarthy JC. Preoperative erythropoietin alpha reduces postoperative transfusions in THA and TKA but may not be cost-effective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(2):590–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3819-z.

Bell GK, Goldhaber SZ. Cost implications of low molecular weight heparins as prophylaxis following total hip and knee replacement. Vasc Med (London, England). 2001;6(1):23–9.

Benninger E, Zingg PO, Kamath AF, Dora C. Cost analysis of fresh-frozen femoral head allografts: is it worthwhile to run a bone bank? Bone Joint J. 2014;96-b(10):1307–11. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.96b10.33486.

Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr, Adams JB. Simultaneous vs staged cementless bilateral total hip arthroplasty: perioperative risk comparison. J Arthroplast. 2007;22(6 Suppl 2):111–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.043.

Bergqvist D, Lindgren B, Matzsch T. Comparison of the cost of preventing postoperative deep vein thrombosis with either unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin. Br J Surg. 1996;83(11):1548–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800831117.

Bernasek TL, Burris RB, Fujii H, Levering MF, Polikandriotis JA, Patterson JJ. Effect on blood loss and cost-effectiveness of pain cocktails, platelet-rich plasma, or fibrin sealant after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2012;27(8):1448–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2012.02.018.

Bilgili MG, Ercin E, Peker G, Kural C, Basaran SH, Duramaz A, et al. Efficiency and cost analysis of cell saver auto transfusion system in total knee arthroplasty. Balk Med J. 2014;31(2):149–53. https://doi.org/10.5152/balkanmedj.2014.13267.

Billote DB, Glisson SN, Green D, Wixson RL. A prospective, randomized study of preoperative autologous donation for hip replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(8):1299–304. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-200208000-00002.

Bjerke-Kroll BT, Sculco PK, McLawhorn AS, Christ AB, Gladnick BP, Mayman DJ. The increased total cost associated with post-operative drains in total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(5):895–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.10.027.

Blin P, Samama CM, Sautet A, Benichou J, Lignot-Maleyran S, Lamarque S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants versus low-molecular weight heparins for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip or knee replacement: a nationwide database cohort study. Pharmacol Res. 2019;141:201–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2018.12.018.

Blumberg N, Kirkley SA, Heal JM. A cost analysis of autologous and allogeneic transfusions in hip-replacement surgery. Am J Surg. 1996;171(3):324–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9610(97)89635-3.

Boese CK, Gallo TJ, Weis M, Baker R, Plantikow CJ, Cooley B. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a blood salvage system in primary total knee arthroplasty‑a retrospective match-controlled chart review. Iowa Orthop J. 2011;31:78–82.

Boese CK, Weis M, Phillips T, Lawton-Peters S, Gallo T, Centeno L. The efficacy of continuous passive motion after total knee arthroplasty: a comparison of three protocols. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(6):1158–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.12.005.

Bolz KM, Crawford RW, Donnelly B, Whitehouse SL, Graves N. The cost-effectiveness of routine follow-up after primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2010;25(2):191–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2008.12.009.

Botteman MF, Caprini J, Stephens JM, Nadipelli V, Bell CF, Pashos CL, et al. Results of an economic model to assess the cost-effectiveness of enoxaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin, versus warfarin for the prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis and associated long-term complications in total hip replacement surgery in the United States. Clin Ther. 2002;24(11):1960–86; discussion 38. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80091-1.

Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Laupacis A, Feeny D, Wong C, Tugwell P, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing cemented to cementless total hip replacement in 250 osteoarthritic patients: the impact on health related quality of life and cost effectiveness. Iowa Orthop J. 1994;14:108–14.

Boylan MR, Riesgo AM, Paulino CB, Sheskier SC. Does Total ankle arthroplasty belong in the comprehensive care for joint replacement? J Foot Ankle Surg. 2018;57(1):69–73. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2017.08.008.

Bozic KJ, Morshed S, Silverstein MD, Rubash HE, Kahn JG. Use of cost-effectiveness analysis to evaluate new technologies in orthopaedics. The case of alternative bearing surfaces in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(4):706–14. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.E.00614.

Bozic KJ, Pui CM, Ludeman MJ, Vail TP, Silverstein MD. Do the potential benefits of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing justify the increased cost and risk of complications? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2301–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-010-1301-0.

Breeman S, Campbell M, Dakin H, Fiddian N, Fitzpatrick R, Grant A, et al. Patellar resurfacing in total knee replacement: five-year clinical and economic results of a large randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(16):1473–81. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.J.00725.

Breeman S, Campbell MK, Dakin H, Fiddian N, Fitzpatrick R, Grant A, et al. Five-year results of a randomised controlled trial comparing mobile and fixed bearings in total knee replacement. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-b(4):486–92. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.95b4.29454.

Briggs A, Sculpher M, Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Malchau H. The use of probabilistic decision models in technology assessment: the case of total hip replacement. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2004;3(2):79–89. https://doi.org/10.2165/00148365-200403020-00004.

Brothers TE, Frank CE, Frank B, Robison JG, Elliott BM, Del Schutte H, et al. Is duplex venous surveillance worthwhile after arthroplasty? J Surg Res. 1997;67(1):72–8. https://doi.org/10.1006/jsre.1996.4962.

Brown ML, Plate JF, Holst DC, Bracey DN, Bullock MW, Lang JE. A retrospective analysis of the merits and challenges associated with simultaneous bilateral THA using the direct anterior approach. Hip Int. 2017;27(2):169–74. https://doi.org/10.5301/hipint.5000449.

Browne JA, Dempsey IJ, Novicoff W, Wanchek T. When would a metal-backed component become cost-effective over an all-polyethylene Tibia in total knee arthroplasty? Am J Orthop (Belle Mead, NJ). 2018;47(6). https://doi.org/10.12788/ajo.2018.0039.

Brunenberg DE, van Steyn MJ, Sluimer JC, Bekebrede LL, Bulstra SK, Joore MA. Joint recovery programme versus usual care: an economic evaluation of a clinical pathway for joint replacement surgery. Med Care. 2005;43(10):1018–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000178266.75744.35.

Bulthuis Y, Mohammad S, Braakman-Jansen LM, Drossaers-Bakker KW, van de Laar MA. Cost-effectiveness of intensive exercise therapy directly following hospital discharge in patients with arthritis: results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(2):247–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.23332.

Callaghan JJ, Liu SS. Ceramic on crosslinked polyethylene in total hip replacement: any better than metal on crosslinked polyethylene? Iowa Orthop J. 2009;29:1–4.

Capra R, Bini SA, Bowden DE, Etter K, Callahan M, Smith RT, et al. Implementing a perioperative efficiency initiative for orthopedic surgery instrumentation at an academic center: a comparative before-and-after study. Medicine. 2019;98(7):e14338. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000014338.

Caprini JA, Arcelus JI, Kudraa JC, Sehgal LR, Oyslender M, Maksimovic D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip replacement. Phlebology. 2002;17(3–4):126–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/026835550201700309.

Chan VWK, Chan PK, Chiu KY, Yan CH, Ng FY. Does barbed suture lower cost and improve outcome in total knee arthroplasty? A randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(5):1474–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.12.015.

Chang P, Okamoto M, Chen J, Frame D. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ondansetron and prochlorperazine for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(4):317–21. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.4.317.

Chawla H, Nwachukwu BU, van der List JP, Eggman AA, Pearle AD, Ghomrawi HM. Cost effectiveness of patellofemoral versus total knee arthroplasty in younger patients. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-b(8):1028–36. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.99b8.Bjj-2016-1032.R1.

Chen JJ, Frame DG, White TJ. Efficacy of ondansetron and prochlorperazine for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after total hip replacement or total knee replacement procedures: a randomized, double-blind, comparative trial. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(19):2124–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.19.2124.

Chen JY, Lo NN, Jiang L, Chong HC, Tay DK, Chin PL, et al. Simultaneous versus staged bilateral unicompartmental knee replacement. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-b(6):788–92. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.95b6.30440.

Chi D, Mariano ER, Memtsoudis SG, Baker LC, Sun EC. Regional Anesthesia and readmission rates after Total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(6):1319–27. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000003830.

Chimento GF, Huff T, Ochsner JL Jr, Meyer M, Brandner L, Babin S. An evaluation of the use of topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2013;28(8 Suppl):74–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.06.037.

Chow J, Fitch DA. In-hospital costs for total hip replacement performed using the supercapsular percutaneously-assisted total hip replacement surgical technique. Int Orthop. 2017;41(6):1119–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-016-3327-8.

Clarke A, Pulikottil-Jacob R, Grove A, Freeman K, Mistry H, Tsertsvadze A, et al. Total hip replacement and surface replacement for the treatment of pain and disability resulting from end-stage arthritis of the hip (review of technology appraisal guidance 2 and 44): systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England). 2015;19(10):1–668, vii-viii. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta19100.

Clement ND, Deehan DJ, Patton JT. Robot-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty for patients with isolated medial compartment osteoarthritis is cost-effective: a markov decision analysis. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-b(9):1063–70. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.101b9.Bjj-2018-1658.R1.

Clement RC, Kamath AF, Derman PB, Garino JP, Lee GC. Bipolar sealing in revision total hip arthroplasty for infection: efficacy and cost analysis. J Arthroplast. 2012;27(7):1376–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2011.11.016.

Cohen EM, Marcaccio S, Goodman AD, Lemme NJ, Limbird R. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of topical vancomycin powder in primary Cementless Total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2019;42(5):e430–e6. https://doi.org/10.3928/01477447-20190321-05.

Colwell CW, Froimson MI, Mont MA, Ritter MA, Trousdale RT, Buehler KC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis with a new mobile device after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2012;27(8):1513–7.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2012.03.024.

Colwell CW Jr, Morris BA. Patient-controlled analgesia compared with intramuscular injection of analgesics for the management of pain after an orthopaedic procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(5):726–33. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-199505000-00009.

Confalonieri N, Manzotti A, Pullen C. Navigated shorter incision or smaller implant in knee arthritis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;463:63–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/BLO.0b013e31811f3a30.

Cool CL, Needham KA, Khlopas A, Mont MA. Revision analysis of robotic arm-assisted and manual Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2019;34(5):926–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.018.

Corman S, Shah N, Dagenais S. Medication, equipment, and supply costs for common interventions providing extended post-surgical analgesia following total knee arthroplasty in US hospitals. J Med Econ. 2018;21(1):11–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2017.1371031.

Courtney PM, Darrith B, Bohl DD, Frisch NB, Della Valle CJ. Reconsidering the affordable care Act's restrictions on physician-owned hospitals: analysis of CMS data on Total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(22):1888–94. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.17.00203.

Courville XF, Tomek IM, Kirkland KB, Birhle M, Kantor SR, Finlayson SR. Cost-effectiveness of preoperative nasal mupirocin treatment in preventing surgical site infection in patients undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(2):152–9. https://doi.org/10.1086/663704.

Dahl OE, Pleil AM. Investment in prolonged thromboprophylaxis with dalteparin improves clinical outcomes after hip replacement. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(5):896–906. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00236.x.

Dakin H, Gray A, Fitzpatrick R, Maclennan G, Murray D. Rationing of total knee replacement: a cost-effectiveness analysis on a large trial data set. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000332. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000332.

Davies DM, Johnston DW, Beaupre LA, Lier DA. Effect of adjunctive range-of-motion therapy after primary total knee arthroplasty on the use of health services after hospital discharge. Can J Surg. 2003;46(1):30–6.

Davies LM, Richardson GA, Cohen AT. Economic evaluation of enoxaparin as postdischarge prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in elective hip surgery. Value Health. 2000;3(6):397–406. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-4733.2000.36005.x.

de Verteuil R, Imamura M, Zhu S, Glazener C, Fraser C, Munro N, et al. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness and economic modelling of minimal incision total hip replacement approaches in the management of arthritic disease of the hip. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England). 2008;12(26):iii–v, ix-223. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta12260.

DeHaan AM, Adams JR, DeHart ML, Huff TW. Patient-specific versus conventional instrumentation for total knee arthroplasty: peri-operative and cost differences. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(11):2065–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2014.06.019.

Demeere JL, Merckx C, Demeere N. Cost minimisation and cost effectiveness in anaesthesia for total hip replacement surgery, in Belgium? A study comparing three general anaesthesia techniques. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2006;57(2):145–51.

Demos HA, Lin ZX, Barfield WR, Wilson SH, Robertson DC, Pellegrini VD Jr. Process improvement project using tranexamic acid is cost-effective in reducing blood loss and transfusions after Total hip and Total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(8):2375–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.068.

Derman PB, Kamath AF, Lee GC. Saline-coupled bipolar sealing in revision total knee arthroplasty for infection. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead, NJ). 2013;42(9):407–11.

Detournay B, Planes A, Vochelle N, Fagnani F. Cost effectiveness of a low-molecular-weight heparin in prolonged prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis after total hip replacement. PharmacoEconomics. 1998;13(1 Pt 1):81–9. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-199813010-00008.

Di Tanna GL, Ferro S, Cipriani F, Bordini B, Stea S, Toni A, et al. Modeling the cost-effectiveness for cement-less and hybrid prosthesis in total hip replacement in Emilia Romagna, Italy. J Surg Res. 2011;169(2):227–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2009.10.031.

Diamantopoulos A, Lees M, Wells PS, Forster F, Ananthapavan J, McDonald H. Cost-effectiveness of rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for the prevention of postsurgical venous thromboembolism in Canada. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(4):760–70. https://doi.org/10.1160/th10-01-0071.

D'Lima DD, Venn-Watson EJ, Tripuraneni P, Colwell CW. Indomethacin versus radiation therapy for heterotopic ossification after hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2001;24(12):1139–43.

Dobosz B, Dutka J, Dutka L, Maleta P. Clinical and cost effectiveness-related aspects of retransfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2012;14(5):421–8. https://doi.org/10.5604/15093492.1016367.

Doman DM, Gerlinger TL. Total joint arthroplasty cost savings with a rapid recovery protocol in a military medical center. Mil Med. 2012;177(1):64–9. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-11-00163.

Dong H, Buxton M. Early assessment of the likely cost-effectiveness of a new technology: a Markov model with probabilistic sensitivity analysis of computer-assisted total knee replacement. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006;22(2):191–202. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266462306051014.

Dramis A, Plewes J. Autologous blood transfusion after primary unilateral total knee replacement surgery. Acta Orthop Belg. 2006;72(1):15–7.

Dranitsaris G, Kahn SR, Stumpo C, Paton TW, Martineau J, Smith R, et al. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of fondaparinux versus enoxaparin for the prevention of thromboembolic events in orthopedic surgery patients. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2004;4(5):325–33. https://doi.org/10.2165/00129784-200404050-00005.

Drummond M, Aristides M, Davies L, Forbes C. Economic evaluation of standard heparin and enoxaparin for prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis in elective hip surgery. Br J Surg. 1994;81(12):1742–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800811212.

Dudley TE, Gioe TJ, Sinner P, Mehle S. Registry outcomes of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty revisions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1666–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0279-3.

Duncan CM, Hall Long K, Warner DO, Hebl JR. The economic implications of a multimodal analgesic regimen for patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery: a comparative study of direct costs. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(4):301–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181ac7f86.

Duncan CM, Moeschler SM, Horlocker TT, Hanssen AD, Hebl JR. A self-paired comparison of perioperative outcomes before and after implementation of a clinical pathway in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2013;38(6):533–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/aap.0000000000000014.

Duran A, Sengupta N, Diamantopoulos A, Forster F, Kwong L, Lees M. Cost and outcomes associated with rivaroxaban vs enoxaparin for the prevention of postsurgical venous thromboembolism from a US payer’s perspective. J Med Econ. 2011;14(6):824–34. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2011.623203.

Duran A, Sengupta N, Diamantopoulos A, Forster F, Kwong L, Lees M. Cost effectiveness of rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for prevention of post-surgical venous thromboembolism from a U.S. payer's perspective. PharmacoEconomics. 2012;30(2):87–101. https://doi.org/10.2165/11599370-000000000-00000.

Dutka J, Dutka L, Janiszewski M, Hajduk G. Cost analysis and sociomedical aspects of the conservative and surgical treatment of hip osteoarthritis. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2008;10(6):537–46.

Duwelius PJ, Brenner JS, Reyner DP, George JC. Cost effectiveness of minimally invasive Total hip arthroplasty. Semin Arthroplast. 2008;19(2):186–93. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sart.2008.02.005.

Duwelius PJ, Moller HS, Burkhart RL, Waller F, Wu Y, Grunkemeier GL. The economic impact of minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2011;26(6):883–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2010.09.011.

Edlin R, Tubeuf S, Achten J, Parsons N, Costa M. Cost-effectiveness of total hip arthroplasty versus resurfacing arthroplasty: economic evaluation alongside a clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001162.

Eggers MD, Fang L, Lionberger DR. A comparison of wound closure techniques for total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2011;26(8):1251–8.e1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2011.02.029.

Elawad A, Benoni G, Montgomery F, Hyddmark U, Persson U, Fredin H. Cost effectiveness of blood substitution in elective orthopedic operations. Acta Orthop Scand. 1991;62(5):435–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453679108996639.

Elbuluk AM, Slover J, Anoushiravani AA, Schwarzkopf R, Eftekhary N, Vigdorchik JM. The cost-effectiveness of dual mobility in a spinal deformity population with high risk of dislocation: a computer-based model. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-b(10):1297–302. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.100b10.Bjj-2017-1113.R3.

Elliott RA, Weatherly HL, Hawkins NS, Cranny G, Chambers D, Myers L, et al. An economic model for the prevention of MRSA infections after surgery: non-glycopeptide or glycopeptide antibiotic prophylaxis? Eur J Health Econ. 2010;11(1):57–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-009-0175-0.

Evans RL, Rubash HE, Albrecht SA. The efficacy of postoperative autotransfusion in total joint arthroplasty. Orthop Nurs. 1993;12(3):11–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006416-199305000-00004.

Farag E, Atim A, Ghosh R, Bauer M, Sreenivasalu T, Kot M, et al. Comparison of three techniques for ultrasound-guided femoral nerve catheter insertion: a randomized, blinded trial. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(2):239–48. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000000262.

Faulkner A, Kennedy LG, Baxter K, Donovan J, Wilkinson M, Bevan G. Effectiveness of hip prostheses in primary total hip replacement: a critical review of evidence and an economic model. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England). 1998;2(6):1–133.

Fawsitt CG, Thom HHZ, Hunt LP, Nemes S, Blom AW, Welton NJ, et al. Choice of prosthetic implant combinations in Total hip replacement: cost-effectiveness analysis using UK and Swedish hip joint registries data. Value Health. 2019;22(3):303–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.08.013.

Feng S, Yang Z, Sun JN, Zhu L, Wang S, Guo KJ, et al. Comparison of the therapeutic effect between the simultaneous and staged unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) for bilateral knee medial compartment arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):340. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2724-8.

Fennema P, Heyse TJ, Uyl-de Groot CA. Cost-effectiveness and clinical implications of advanced bearings in total knee arthroplasty: a long-term modeling analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2014;30(2):218–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266462314000129.

Fernandes L, Roos EM, Overgaard S, Villadsen A, Søgaard R. Supervised neuromuscular exercise prior to hip and knee replacement: 12-month clinical effect and cost-utility analysis alongside a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1369-0. A full economic evaluation of an RCT comparing a supervised neuromuscular exercise program and preoperative educational package to the preoperative educational package alone prior to total joint arthroplasty that scored a perfect 100 on the Quality of Health Economics Studies (QHES) tool. The paper provides a great reference for researchers when designing studies and drafting manuscripts or for critical appraisal of studies.

Fitzpatrick R, Shortall E, Sculpher M, Murray D, Morris R, Lodge M, et al. Primary total hip replacement surgery: a systematic review of outcomes and modelling of cost-effectiveness associated with different prostheses. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England). 1998;2(20):1–64.

Fordham R, Skinner J, Wang X, Nolan J. The economic benefit of hip replacement: a 5-year follow-up of costs and outcomes in the Exeter Primary Outcomes Study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000752.

Friedman RJ, Dunsworth GA. Cost analyses of extended prophylaxis with enoxaparin after hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;370:171–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200001000-00016.

Friesen E, Lier D, Bachynsky J, Jacobs P. An economic comparison of enoxaparin and warfarin in the prevention of deep vein thrombosis after hip and knee replacement. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2002;55:128–35.

Froemke CC, Wang L, DeHart ML, Williamson RK, Ko LM, Duwelius PJ. Standardizing care and improving quality under a bundled payment initiative for Total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2015;30(10):1676–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2015.04.028.

Furnes A, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Vollset SE. The economic impact of failures in total hip replacement surgery: 28,997 cases from the Norwegian arthroplasty register, 1987-1993. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67(2):115–21. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453679608994653.

Fusco F, Campbell H, Barker K. Rehabilitation after resurfacing hip arthroplasty: cost-utility analysis alongside a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2019;33(6):1003–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215519827628. A full economic evaluation of an RCT comparing telerehabilitation to usual care after total knee arthroplasty that scored a perfect 100 on the Quality of Health Economics Studies (QHES) tool. The paper also completes both a cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis. The paper provides a great reference for researchers when designing studies and drafting manuscripts or for critical appraisal of studies.

Fusco F, Turchetti G. Telerehabilitation after total knee replacement in Italy: cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis of a mixed telerehabilitation-standard rehabilitation programme compared with usual care. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e009964. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009964.

Ghomrawi HM, Eggman AA, Pearle AD. Effect of age on cost-effectiveness of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty compared with total knee arthroplasty in the U.S. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(5):396–402. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.N.00169.

Gililland JM, Anderson LA, Barney JK, Ross HL, Pelt CE, Peters CL. Barbed versus standard sutures for closure in total knee arthroplasty: a multicenter prospective randomized trial. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(9 Suppl):135–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.041.

Gill J, Chase E, Rosenstein A. The use of tranexamic acid in revision total hip arthroplasty: a pilot study. Curr Orth Pract. 2009;20:152–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/BCO.0b013e318191ebc0.

Gillette BP, Maradit Kremers H, Duncan CM, Smith HM, Trousdale RT, Pagnano MW, et al. Economic impact of tranexamic acid in healthy patients undergoing primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2013;28(8 Suppl):137–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.054.

Gioe TJ, Sharma A, Tatman P, Mehle S. Do "premium" joint implants add value?: analysis of high cost joint implants in a community registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(1):48–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-010-1436-z.

Gioe TJ, Sinner P, Mehle S, Ma W, Killeen KK. Excellent survival of all-polyethylene tibial components in a community joint registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:88–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/BLO.0b013e31812f7879.

Glennie RA, Korczak A, Naudie DD, Bryant DM, Howard JL. MONOCRYL and DERMABOND vs Staples in Total hip arthroplasty performed through a lateral skin incision: a randomized controlled trial using a patient-Centered assessment tool. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(8):2431–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.042.

Gonano C, Leitgeb U, Sitzwohl C, Ihra G, Weinstabl C, Kettner SC. Spinal versus general anesthesia for orthopedic surgery: anesthesia drug and supply costs. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(2):524–9. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000194292.81614.c6.

Goodnough LT, Despotis GJ, Merkel K, Monk TG. A randomized trial comparing acute normovolemic hemodilution and preoperative autologous blood donation in total hip arthroplasty. Transfusion. 2000;40(9):1054–7. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40091054.x.

Gordois A, Posnett J, Borris L, Bossuyt P, Jonsson B, Levy E, et al. The cost-effectiveness of fondaparinux compared with enoxaparin as prophylaxis against thromboembolism following major orthopedic surgery. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(10):2167–74. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00396.x.

Gothesen O, Slover J, Havelin L, Askildsen JE, Malchau H, Furnes O. An economic model to evaluate cost-effectiveness of computer assisted knee replacement surgery in Norway. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:202. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-14-202.

Gower A, Hussein AI, Briggs PJ, Dewar MS. Blood utilization in hip and knee arthroplasty: a cost-minimization study. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43(6):397–9.

Graves N, Halton K, Lairson D. Economics and preventing hospital-acquired infection: broadening the perspective. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(2):178–84. https://doi.org/10.1086/510787.

Green WS, Toy P, Bozic KJ. Cost minimization analysis of preoperative erythropoietin vs autologous and allogeneic blood donation in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2010;25(1):93–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2008.10.005.

Gustke KA, Gelbke MK. All-polyethylene Tibial component use for elderly, low-demand Total knee arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(8):2421–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.077.

Gutowski CJ, Zmistowski BM, Clyde CT, Parvizi J. The economics of using prophylactic antibiotic-loaded bone cement in total knee replacement. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-b(1):65–9. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.96b1.31428.

Gutowski CJ, Zmistowski BM, Lonner JH, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Direct costs of aspirin versus warfarin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after Total knee or hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2015;30(9 Suppl):36–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2015.04.048.

Haentjens P, De Groote K, Annemans L. Prolonged enoxaparin therapy to prevent venous thromboembolism after primary hip or knee replacement. A cost-utility analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(8):507–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-004-0720-3.

Halleberg Nyman M, Gustafsson M, Langius-Eklof A, Johansson JE, Norlin R, Hagberg L. Intermittent versus indwelling urinary catheterisation in hip surgery patients: a randomised controlled trial with cost-effectiveness analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(12):1589–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.05.007.

Hamidi V, Ringerike T, Hagen G, Reikvam A, Klemp M. New anticoagulants as thromboprophylaxis after total hip or knee replacement. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29(3):234–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266462313000251.

Hamilton DF, Clement ND, Burnett R, Patton JT, Moran M, Howie CR, et al. Do modern total knee replacements offer better value for money? A health economic analysis. Int Orthop. 2013;37(11):2147–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-013-1992-4.

Hansen TB, Jacobsen F, Larsen K. Cost effective interprofessional training: an evaluation of a training unit in Denmark. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(3):234–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820802602420.

Happe LE, Farrelly EM, Stanford RH, Sarnes MW. Cost and occurrence of thrombocytopenia in patients receiving venous thromboembolism prophylaxis following major orthopaedic surgeries. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2008;26(2):125–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-007-0170-1.

Harper RA, Sucher MG, Giordani M, Nedopil AJ. Topically applied epsilon-aminocaproic acid reduces blood loss and length of hospital stay after total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2017;40(6):e1044–e9. https://doi.org/10.3928/01477447-20170925-07.

Hawker GA, Badley EM, Croxford R, Coyte PC, Glazier RH, Guan J, et al. A population-based nested case-control study of the costs of hip and knee replacement surgery. Med Care. 2009;47(7):732–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181934553.

Hawkins DW, Langley PC, Krueger KP. Pharmacoeconomic model of enoxaparin versus heparin for prevention of deep vein thrombosis after total hip replacement. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1997;54(10):1185–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/54.10.1185.

Hawkins DW, Langley PC, Krueger KP. A pharmacoeconomic assessment of enoxaparin and warfarin as prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis in patients undergoing knee replacement surgery. Clin Ther. 1998;20(1):182–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80045-3.

Healy WL, Iorio R, Ko J, Appleby D, Lemos DW. Impact of cost reduction programs on short-term patient outcome and hospital cost of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(3):348–53. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-200203000-00003.

Hebert CK, Williams RE, Levy RS, Barrack RL. Cost of treating an infected total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;331:140–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-199610000-00019.

Heintzbergen S, Kulin NA, Ijzerman MJ, Steuten LM, Werle J, Khong H, et al. Cost-utility of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing compared to conventional total hip replacement in young active patients with osteoarthritis. Value Health. 2013;16(6):942–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2013.06.021.

Hejblum G, Atsou K, Dautzenberg B, Chouaid C. Cost-benefit analysis of a simulated institution-based preoperative smoking cessation intervention in patients undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasties in France. Chest. 2009;135(2):477–83. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-0897.

Henson KS, Thomley JE, Lowrie LJ, Walker D. Comparison of selected outcomes associated with two postoperative analgesic approaches in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. AANA J. 2019;87(1):51–7.

Herbold JA, Bonistall K, Walsh MB. Rehabilitation following total knee replacement, total hip replacement, and hip fracture: a case-controlled comparison. J Geriatr Phys Ther (2001). 2011;34(4):155–60. https://doi.org/10.1519/JPT.0b013e318216db81.

Higashi H, Barendregt JJ. Cost-effectiveness of total hip and knee replacements for the Australian population with osteoarthritis: discrete-event simulation model. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25403. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025403.

Ho DM, Huo MH. Are critical pathways and implant standardization programs effective in reducing costs in total knee replacement operations? J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(1):97–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.03.009.

Hodge WA. Prevention of deep vein thrombosis after total knee arthroplasty. Coumadin versus pneumatic calf compression. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;271:101–5.

Honorato J, Gomez-Outes A, Navarro-Quilis A, Martinez-Gonzalez J, Rocha E, Planes A. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of bemiparin and enoxaparin as prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in total knee replacement surgery. PharmacoEconomics. 2004;22(13):885–94. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200422130-00006.

Hsieh PH, Huang KC, Lee PC, Lee MS. Two-stage revision of infected hip arthroplasty using an antibiotic-loaded spacer: retrospective comparison between short-term and prolonged antibiotic therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64(2):392–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkp177.

Hsu AR, Gross CE, Bhatia S, Levine BR. Template-directed instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty: cost savings analysis. Orthopedics. 2012;35(11):e1596–600. https://doi.org/10.3928/01477447-20121023-15.

Huang SW, Chen PH, Chou YH. Effects of a preoperative simplified home rehabilitation education program on length of stay of total knee arthroplasty patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(3):259–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2011.12.004.

Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, Vanness D, Larson D, Trousdale R, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28–38. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-1-200407060-00012.

Hunt GR, Crealey G, Murthy BV, Hall GM, Constantine P, O'Brien S, et al. The consequences of early discharge after hip arthroplasty for patient outcomes and health care costs: comparison of three centres with differing durations of stay. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(12):1067–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509339000.

Hyland SJ, Deliberato DG, Fada RA, Romanelli MJ, Collins CL, Wasielewski RC. Liposomal bupivacaine versus standard periarticular injection in total knee arthroplasty with regional anesthesia: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplast. 2019;34(3):488–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.11.026.

Ilfeld BM, Mariano ER, Williams BA, Woodard JN, Macario A. Hospitalization costs of total knee arthroplasty with a continuous femoral nerve block provided only in the hospital versus on an ambulatory basis: a retrospective, case-control, cost-minimization analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32(1):46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rapm.2006.10.010.

Iorio R, Healy WL, Patch DA, Appleby D. The role of bladder catheterization in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;380:80–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200011000-00011.

Iorio R, Whang W, Healy WL, Patch DA, Najibi S, Appleby D. The utility of bladder catheterization in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;432:148–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000149823.57513.00.

Irisson E, Hemon Y, Pauly V, Parratte S, Argenson JN, Kerbaul F. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and financial cost in primary total hip and knee replacement surgery. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(5):477–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2012.05.002.

Jackson BR, Umlas J, AuBuchon JP. The cost-effectiveness of postoperative recovery of RBCs in preventing transfusion-associated virus transmission after joint arthroplasty. Transfusion. 2000;40(9):1063–6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40091063.x.

Jacobson JJ, Schweitzer SO, Kowalski CJ. Chemoprophylaxis of prosthetic joint patients during dental treatment: a decision-utility analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72(2):167–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(91)90159-a.

Jiang Y, Du H, Liu J, Zhou Y. Aspirin combined with mechanical measures to prevent venous thromboembolism after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Chin Med J. 2014;127(12):2201–5.

Johansson T, Pettersson LG, Lisander B. Tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty saves blood and money: a randomized, double-blind study in 100 patients. Acta Orthop. 2005;76(3):314–9.

Johnson CB, Steele-Moses SK. The use of continuous femoral nerve blocks versus extended release epidural morphine: a study comparing outcomes in total knee arthroplasty procedures. Orthop Nurs. 2011;30(1):44–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/NOR.0b013e31820574b2.

Johnson JP, Kleiner J, Goodman AD, Gil JA, Daniels AH, Hayda RA. Treatment of femoral neck fractures in patients 45-64 years of age. Injury. 2019;50(3):708–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2018.11.020.

Jonas SC, Shah R, Mitra A, Deo SD. 5-year cost/benefit analysis of revision of failed unicompartmental knee replacements (UKRs); not "just" a primary total knee replacement (TKR). Knee. 2014;21(4):840–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2014.04.012.

Jones HW, Savage L, White C, Goddard R, Lumley H, Kashif F, et al. Postoperative autologous blood salvage drains--are they useful in primary uncemented hip and knee arthroplasty? A prospective study of 186 cases. Acta Orthop Belg. 2004;70(5):466–73.

Jordan LR, Siegel JL, Olivo JL. Early flexion routine. An alternative method of continuous passive motion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;315:231–3.