Abstract

The purpose of this study is twofold: first, to establish the current themes on the topic of manufacturing and supply chain flexibility (MSCF), assess their level of maturity in relation to each other, identify the emerging ones and reflect on how they can inform each other, and second, to develop a conceptual model of MSCF that links different themes connect and highlight future research opportunities. The study builds on a sample of 222 articles published from 1996 to 2018 in international, peer-reviewed journals. The analysis of the sample involves two complementary approaches: the co-word technique to identify the thematic clusters as well as their relative standing and a critical reflection on the papers to explain the intellectual content of these thematic clusters. The results of the co-word analysis show that MSCF is a dynamic topic with a rich and complex structure that comprises five thematic clusters. The value chain, capability and volatility clusters showed research topics that were taking a central role in the discussion on MSCF but were not mature yet. The SC purchasing practices and SC planning clusters involved work that was more focused and could be considered more mature. These clusters were then integrated in a framework that built on the competence–capability perspective and identified the major structural and infrastructural elements of MSCF as well as its antecedents and consequences. This paper proposes an integrative framework helping managers keep track the various decisions they need to make to increase flexibility from the viewpoint of the entire value chain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Flexibility has long been a fundamental concept in operations management. The increasing demand for customized products and the volatility in business environments due to social, political, economic and natural factors have kept flexibility on the agenda of both managers and academics, as it is an effective coping mechanism with such forces (Merschmann and Thonemann 2011; Seebacher and Winkler 2013; Blomé et al. 2014; Xiao 2015; Ali and Murshid 2016; Teich and Claus 2017; Kaur et al. 2017). It has been discussed as part of operations strategy (Dey et al. 2019), as a cross-functionally and an inter-organizationally derived competence as well as a multidimensional, hierarchical system (Yu et al. 2015).

The earliest research on flexibility—commonly called manufacturing flexibility (MF)—considered it as part of operations strategy, examining its role among other competitive priorities, including cost, quality and delivery (Hayes and Wheelwright 1984). Particularly, manufacturing flexibility has been defined as the capability to react effectively (Mishra et al. 2014; Solke and Singh 2018) to competitive threats (Oberoi et al. 2007) adopting an internal and firm-specific view. MF research has a history of at least 3 decades (Sharma and Sushil 2002; Koste et al. 2004) and its maturity is evident from the large body of research on this topic encompassing multiple conceptualizations and frameworks (Beach et al. 2000; Jain et al. 2013, Mishra et al. 2014; Yu et al. 2015; Pérez-Pérez et al. 2016; Kumar and Mishra 2017; or Pérez-Pérez et al. 2018). In time, the focus of research shifted from this internal and firm-specific view, to the more contemporary concept of an external, supply chain-driven flexibility (Wadhwa et al. 2008a, b; Bernardes and Hanna 2009; Stevenson and Spring 2009; Malhotra and Mackelprang 2012; Kumar et al. 2013; Thomé et al. 2014; Xiao 2015; Esmaeilikia et al. 2016; Shibin et al. 2016; Chatzikontidou et al. 2017; Kumar and Mishra 2017; Maestrini et al. 2017; Song et al. 2018). Supply chain flexibility (SCF) is defined as “the ability to rapidly reconfigure key supply chain (SC) resources in an attempt to maintain competitiveness” (Rojo et al. 2018, p. 637). It follows a logical extension of MF (Lummus et al. 2003; Singh and Acharya 2013, 2014; Tiwari et al. 2015) complementing components of flexibility inherent at the firm level together with those at the inter-firm level (Stevenson and Spring 2007) derived from inter-organizational core processes in procurement/sourcing and distribution/logistics (Duclos et al. 2003; Singh and Sharma 2014; Esmaeilikia et al. 2016). Thus, SCF is a much broader concept, considering flexibility from the perspective of the entire value chain (Merschmann and Thonemann 2011; Singh and Sharma 2014) that has emerged as a potential weapon to deal with current competitive uncertainties and associated risks (Chirra and Kumar 2018).

The concepts of MF and SCF are strongly interlinked—the conceptual development of SCF exploits the knowledge gained in manufacturing flexibility research—but still distinct (Merschmann and Thonemann 2011; Kumar and Mishra 2017). As a consequence, “there is growing interest in the intersection of these two related, strategic concepts” (Li et al. 2018, 1), which collectively emerge “as the key objective for manufacturers and industrial supply chains” (Seebacher and Winkler 2013, 3415). The discussion of manufacturing and supply chain flexibility (MSCF) can prove useful for at least three reasons. One, there is value in taking an integrated perspective of the current state of these themes to understand its evolution and future direction. Two, it helps understand what kind of investments elevate flexibility by strengthening both MF and SCF simultaneously (Rao and Wadhwa 2002; Kumar and Deshmukh 2006; Kumar and Mishra 2017). Three, this review helps identify the antecedents and consequences of MSCF, the latter of which shows its relation to the wider SC field and link to other complex SC concepts such as SC agility (Fayezi et al. 2017).

For these reasons, the main purpose of the paper is to provide a general overview of the status, trends and potential future research areas of MSCF field applying systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis that identifies thematic areas of MSCF trough co-words. Co-word is a systematic and objective technique that focuses on the knowledge structure of the area studied. Thus, identifying the main topics of a research domain, assessing their level of development relative to each other, pinpointing the emerging ones and reflect on how these various themes can inform each other (Verbeek et al. 2002; Cobo et al. 2011). This study extends previous research on MSCF, such as Seebacher and Winkler (2013) and Kumar and Mishra (2017) through a systematic literature review of the most up-to-date research. Consequently, this paper contributes to the previous literature in four ways. First, the literature review covers until July 2018 and uses a large number of social sciences databases that helps to avoid potential bias towards a subset of journals and the likelihood of omitting significant work in this field. Second, we provide a systematic literature review, which starts when the scientific attention on flexibility began to grow in 1996 (Seebacher and Winkler 2013) and captures the fast-growing number of publications during the last 2 decades (Kumar and Mishra 2017). Third, it complements studies using co-citation analysis (Seebacher and Winkler 2013; Tiwari et al. 2015), where can one establish the intellectual base of a research field rather than the content picture of the research topics (Cobo et al. 2011). In co-citation analysis, for many articles, it also takes time to start getting cited heavily and thus get picked up by the analysis (Feng et al. 2017). Four, based on a critical reflection on the different thematic clusters identified by co-words, this study advances on the development of an integrative conceptual model by identifying research opportunities to make future research investments more productive.

The co-word analysis resulted in the identification of five thematic clusters: the value chain, capability and volatility clusters showed research topics that were taking a central role in the discussion on MSCF but were not mature yet. The SC purchasing practices and SC planning clusters involved work that was more focused and could be considered more mature. These clusters were then integrated in a framework that built on the competence–capability perspective and identified the major structural and infrastructural elements of MSCF as well as it antecedents and consequences.

The next section explains the methodology used in our literature review. Section three critically analyses the results, and section four discusses opportunities for future research through an integrative framework.

Methodology

The analysis started with literature search. Literature reviews are used to evaluate past body of literature through a systematic design that provides a general overview of the status, trends and potential future research areas of a research field. It is an integral part of the research process and makes a valuable contribution to almost every step of the research design. That is because literature reviews contribute to establishing the theoretical roots of a research study, clarifying research ideas and developing their research methodology. Also, literature review “serves to enhance and consolidate knowledge base and helps researchers to integrate their findings with the existing body of knowledge” (Kumar 2019, p. 46), thus contributing to the contextualization of research findings. In summary, literature review gives an insight into what other researchers have done on a subject matter and what is yet to be done.

Systematic reviews include an iterative cycle of determining primary and secondary search keywords for retrieving a sample of relevant literature followed up with a synthesis of the research to date as well as reflection on future opportunities. To this end, we use a three-step methodology (Durach et al. 2017; Maestrini et al. 2017) that is presented below:

Step 1: Collection of Past Literature and Evaluation for Appropriateness

A systematic keyword-based search covering six social sciences databases (Gligor and Holcomb 2012; Tiwari et al. 2015; Simangunsong et al. 2016; Moreira and Tjahjono 2016; Pérez-Pérez et al. 2018; Merigó et al. 2019), namely Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), SCOPUS, JSTOR, ABI, Business Source Complete and Science Direct, was performed in July 2018.

To ensure that we capture the overlap between MF and SCF, we included “suppl* chain* flexib*” and “manufact* flexib*” and the co-occurring terms “flexib* suppl* chain*”, “operat* flexib*” and “production flexib*” as primary terms of the search (Seebacher and Winkler 2013; Serrano-Bedia et al. 2013; Tiwari et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2015; Esmaeilikia et al. 2016; Singh et al. 2017). Additionally, the broader term “supply chain*” was included as a secondary keyword to guarantee the search being sufficiently inclusive to capture most relevant articles within the scope of our research objective. Thus, nine different Boolean two-by-two combinations of these primary and secondary keywords were used (see Fig. 1), considering as search criteria title, abstract and keywords, in line with the previous research (Fahimnia et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2015; Esmaeilikia et al. 2016; Grover and Kar 2017; Brozovic 2018; Abdelilah et al. 2018). Specifically, to capture the intersection of the MF and SCF domains, the connector AND was selected for these two-by-two combinations. Truncation symbol “*” was used to search all the ending variants of the selected keywords (Harkonen et al. 2015). This initial search attempts resulted in a total of 575 articles that was gradually cut down for appropriateness (see Fig. 1).

From 575 papers, those appearing in more than one database (192) were deleted, leaving 383 unique documents. Subsequently, two complementary searches were performed. Firstly, all references of the sampled papers (backward snowball search) and all works that cited papers contained in the sample (forward snowball search) were checked well through the use of Google Scholar as a secondary platform for completeness (Moussaoui et al. 2016). Secondly, those journals in our sample containing “Flexible” or “Flexibility” in the title and currently indexed in JCR (Journal Citation Reports) or SJR (Scimago Journal & Country Rank) were re-examined by extending the search of selected keyword combinations from title, abstract and keywords to “all fields”. Nineteen and 50 additional papers were identified, respectively, thus increasing the sample to 452.

Then, to guarantee reliability, the sample was screened for content refinement. Although in most cases the lack of fit with article’s scope could be identified from the title, abstract and keywords, sometimes it was necessary to read the article to ascertain its suitability. For this reason, and to gain sample robustness, all the authors of this paper examined those articles for which their research domain was unclear, until an agreement is reached. Furthermore, papers containing keyword combinations only in the references list were removed from the sample (Fahimnia et al. 2015; Tiwari et al. 2015; Musa and Dabo 2016), leading to a final sample of 222 papers.

Step 2: Thematic Identification Through Bibliometric Analysis: Co-word Technique

The co-word technique uses the keywords of a sample of studies to identify the major themes in the domain of interest, which are then analysed and interpreted (López-Fernández et al. 2016). The technique is based on a simple principle: the co-occurrence of particular keywords in individual papers collectively can help us identify the major research themes on a specific topic, in our case manufacturing and supply chain flexibility (Callon et al. 1995). Co-word analysis involves two steps: one, identification of thematic clusters and the networks of keywords that define each of them and two, a graphical representation of the thematic clusters’ maturity relative to each other, called the strategic matrix. Both steps, obtained through the specific bibliometric computer program REDES2005, are explained below.

The thematic clusters and the networks of keywords that define each of them are identified by the strength of the union of these keywords. In order to measure this strength, the frequency at which two keywords co-occur within a paper is measured by a normalized index, getting a symmetrical co-occurrence matrix. The value of this index depends on the frequency at which both keywords occur independently and their joint appears. The normalized index is calculated as eij = c2ij/cicj where cij is the number of documents in which two keywords i and j co-occur and ci and cj represent the number of documents in which each one appears. In REDES2005, the keywords are clustered into themes by using the simple centre algorithm (Coulter et al. 1998; Cobo et al. 2011). The keywords that represent the clusters and the papers in the clusters are then reviewed by the researcher to identify the themes.

The graphical representation of the thematic clusters’ standing relative to each other is constructed in REDES2005 using two dimensions: centrality and density (please refer to Callon et al. (1995) or Benavides-Velasco et al. (2013) for technical details). Centrality measures how often the theme under question appears with the other themes in the field, being understood as a measure of the importance of a theme in entire research field analysed. Density measures the strength of relations between the keywords that define a theme. It captures how well developed a theme is. Centrality (cr) and density (dr), are calculated as:

where rankci is the position of theme i among all the themes that have been sorted in ascending order with respect to centrality. Rankdi is the same with respect to density. N is the total number of themes and is used to standardize cr and dr values to the range [0, 1] (Muñoz-Leiva et al. 2012).

The combination of both parameters allows to map the research clusters within four possible quadrants of the strategic matrix. Core/central clusters, located in the upper right quadrant, are both well developed and take a quite central role in that field. Specialization clusters, located in the upper left quadrant, are well developed but are more niche themes. Peripheral clusters, located in the lower left quadrant, are both weakly developed and marginal. Emergent clusters, located in the lower right quadrant, are fundamental for the overall research domain but not yet well developed. The field’s overall level of maturity is determined by the collective configuration of all of the clusters (please see Callon et al. (1995) page 79 for specific details of meaning of strategic matrix positions).

Step 3: Labelling the Thematic Clusters and Critical Reflection

In order to complement and enrich the results of the previous step, a more fine-grained process is carried out (Maestrini et al. 2017) in order to identify potential future research areas of the research domain analysed and synthesizing them in an integrative framework. It consists, firstly, of a close examination of each of the articles in each thematic cluster to collect information about the main theoretical and methodological aspects, results and gaps identified. Secondly, all authors worked, both independently and together, to characterize the focus of the articles in each cluster and how they contribute to MSCF domain (Di Stefano et al. 2010).

Findings

This study concurs with the vast literature that considers SCF an extension of the flexibility beyond the manufacturing enterprise (MF) to a broader concept from the viewpoint of the entire value chain (Vickery et al. 1999; Blomé et al. 2013; Tiwari et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2015; Kumar and Mishra 2017). Unlike MF, defined as an ability to react effectively (Mishra et al. 2014; Solke and Singh 2018; Pérez-Pérez et al. 2018) to competitive threats (Oberoi et al. 2007) adopting a firm-specific view that considers merely the physical resources employed in manufacturing processes, “SCF entails the implicit requirement of flexibility within and between all partners in the chain” (Tiwari et al. 2015, p. 768). Thus, SCF complements flexibility inherent at the firm level together with flexibility at the inter-firm level (Stevenson and Spring 2007) derived from inter-organizational core processes in procurement/sourcing and distribution/logistics (Duclos et al. 2003; Singh and Sharma 2014; Esmaeilikia et al. 2016).

Different from recent bibliometric reviews adopting either citation analysis (e.g. Seebacher and Winkler 2013; Tiwari et al. 2015) or meta-analysis (e.g. Yu et al. 2015), co-word analysis is employed in this paper to address a general overview of the status, trends and potential future research areas of MSCF. As a complement of co-word analysis, this study identifies temporal distribution of scientific contributions and journal productivity in the MSCF field. Specific results are described below.

Figure 2 shows the number papers per year to illustrate the evolution of this area. The figure captures the fast-growing number of publications during the last 2 decades. Particularly, since the early 2000s papers on MSCF have been published regularly. The number of articles peaked during 2009–2014 and continued steadily since then, suggesting an enduring interest in the topic.

Table 1 shows journal productivity in the field. The research in the area is spread across a number of high-quality publications including International Journal of Production Economics, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, International Journal of Production Research, Journal of Operations Management, and Global Journal of Flexible Systems management as the top five leading the list with over 10 papers each. The high number of papers on MSCF in these journals, which are papers from a wide array of operations and supply chain topics, could indicate the level of interest in this topic.

By using co-word analysis for mapping science, clusters of keywords are obtained. In this case, the co-word analysis resulted in five thematic clusters. The keywords that delineate them are provided in Table 2. Clusters of keywords are particularly useful to future researchers and help them choose the most appropriate search keywords depending on their topic of interest (López-Fernández et al. 2016). In line with previous studies co-words were examined from available metadata such as author and index keywords provided by the six databases used on this study (Calma et al. 2019).

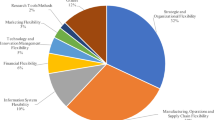

Then, each research cluster obtained in co-word analysis is mapped into a two-dimensional space which is shown in Fig. 3 by two parameters (“density” and “centrality”). According to the quadrant in which they are placed, we can find four kinds of clusters (see step 2 in “Methodology” section). Results in Fig. 3 show that MSCF field is still not fully developed. Two clusters are specialized—purchasing and planning—and the remaining three clusters—value chain, capability and volatility—are emergent and encompass transversal and important themes for MSCF field that they are not still well developed (Callon et al. 1995). Furthermore, a critical analysis revealed that the two biggest clusters identified have a high dynamism because they are composed of different sub-themes showing a rich and complex structure.

Figure 4 shows the articles published per year in each thematic cluster and, if available, its sub-themes between 1996 and 2018. Of the emergent clusters, the value chain and the volatility clusters seem to have been established more recently, in the early 2000s. Furthermore, both encompass sub-themes. All of the sub-themes have seen regular coverage, except for the distribution sub-theme, for which the published papers are almost all between 2010 and 2013. The capability cluster suggests regular research over the years. As for the two specialization clusters, the planning cluster shows a more recent and relatively constant stream of published papers, while the number of articles on purchasing shows a slowdown.

Using the clusters and sub-streams identified by the co-word analysis, Table 3 provides a general and comprehensive portrayal of each cluster and its subsequent sub-streams and the supporting literature base for each for guaranteeing literature review’s traceability.

Considering the rich tradition and complexity of each cluster, far more than its label suggests, we next proceed to provide a critical analysis of them:

Value chain cluster (44.14%) It concentrates the greatest number of papers and includes those papers that address some fundamental concerns of the field. While it does not rate highest on centrality and density, the body of literature in this thematic cluster and its closeness in position to the upper left quadrant suggest it to be the most fully developed among all the themes.

Specifically, the MSCF conceptualization and operationalization stream addresses several issues for the development and consolidation of the field, such as the conceptualization (Stevenson and Spring 2007; Reichhart and Holweg 2007; Bernardes and Hanna 2009; Esmaeilikia et al. 2016), operationalization (Saghiri 2011; Moon et al. 2012; Maestrini et al. 2017) and research evolution (Seebacher and Winkler 2013; Tiwari et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2015) of manufacturing and supply chain flexibilities, individually and in relation to each other. Other research lines raise more general questions about MSCF. Moving from the strategic to the operational.

The strategic MSCF management stream predominantly comprises qualitative studies on SC design (i.e. Goldsby and García-Dastugue 2003; Chandra et al. 2010). One line of research offers conceptual models on MSCF-related decision-making (Kumar et al. 2006; Manuj and Sahin 2011), while another investigates the effect of different MSCF design options (Salvador et al. 2007; Engelhardt-Nowitzki 2012; Tanrisever et al. 2012; Singh and Sharma 2014) and MSCF policies’ design (Lee and Kincade 2003; Soon and Udin 2011) on SC performance. The quantitative articles in this research line explore the relationships between SC strategy, manufacturing flexibility, visibility and performance. In general, the studies find evidence of positive direct effects of SC strategy on MSCF (Fantazy et al. 2009) and of MSCF on performance (Lo 2016; Dansereau et al. 2014). The effects of MSCF options and policies on SC sustainability are also of interest (Chandra et al. 2010; Dansereau et al. 2014; Fantazy and Salem 2016).

The collaboration and MSCF stream advocates strategic and integrated view of upstream production to obtain a competitive advantage (Omar et al. 2012). Most papers are empirical, with a limited presence of theoretical research discussing how MF is affected by the bullwhip effectFootnote 1 (Richardson 1996; Stank et al. 2001; Kayis and Kara 2005) and outsourcing (Dabhilkar and Bengtsson 2008; Fredriksson 2014). The most recent qualitative (Scherrer-Rathje et al. 2014; Manders et al. 2016) and quantitative empirical studies (Omar et al. 2012; He et al. 2014; Willis et al. 2016) build on strategic management theories and extend the collaboration–flexibility–performance relationship with the incorporation of inter-organizational information systems. These systems are considered a prerequisite for building effective cooperative relationships by allowing the sharing of real time information between business partners (Pierre and Luc 2007; Kume and Fujiwara 2016). Among the most frequently analysed inter-organizational systems are virtual integration, collaborative product commerce or vendor-managed inventory (Banker and Bardhan 2006; Wang et al. 2006).

Finally, the distribution and MSCF stream predominantly comprises case studies centred on transportation planning decisions, in both forward logistics (Yu et al. 2012, 2013; Ishfaq 2013) and reverse logistics (Sasikumar and Haq 2010; Bai and Sarkis 2013). Forward logistics has a more extensive empirical tradition in evaluating key logistic capabilities to ensure SC stability. The role of different transportation flexibility options in various contexts has been explored (Naim et al. 2010; Lagoudis et al. 2010). These vary from international distribution centre operations (Yu et al. 2012, 2013) to the container liner shipping sector (Mason and Nair 2013a, b). By contrast, there is little research on reverse logistic flexibility. It focuses on operational decision-making, such as choice of logistic operating modes (Sasikumar and Haq 2010) or programmatic evaluation (Bai and Sarkis 2013). The results suggest that, in general, reverse logistic networks are more complex than that of forward logistics, thus increasing the information management requirements.

The volatility cluster (22.98%) focuses on the link between MSCF and uncertainty (Fayezi et al. 2014). It is composed of three sub-themes.

The MSCF and business uncertainty stream sheds light on the use of MF—by type and level—to cope with uncertainty (Calvo et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2016). Much of the work within this line examines, either theoretically (Garavelli 2003; Sawhney 2006) or through case studies (Scavarda et al. 2015; Simangunsong et al. 2016), how the different flexibility strategies adopted by SC partners in response to various types of business uncertainties match (Candace et al. 2011). The limited quantitative studies explore either the direct (Wang et al. 2006; Nagarajan et al. 2013; Kim and Chai 2016) or the moderating (Wong et al. 2011; Qu et al. 2014) effects of business uncertainty on the MSCF performance relationship, as well as the development of MSCF capability to respond to dynamic and turbulent environments (Zhang et al. 2005; Lim et al. 2010, 2012). Theoretically, these quantitative studies tend to build on contingency theory (Wong et al. 2011; Kim and Chai 2016) or resource-based view (Zhang et al. 2005; Sawhney 2006; Nagarajan et al. 2013). This stream highlights the importance of matching flexibility strategies to the business uncertainty experienced (Candace et al. 2011; Fayezi et al. 2014).

The MSCF and risk management stream is dominated by conceptual and modelling-based papers. The general relationship between SC risk management and flexibility is well established; different forms of flexibility are some of the most effective options for risk mitigation (Bandaly et al. 2012) and even in reducing the link between business uncertainty and SC risks. MSCF has particularly received attention with respect to stakeholder-driven risks (Bandaly et al. 2013). Supply contracts are an effective means to reduce such stakeholder-driven risks and can be used to complement operational flexibility types (Reimann and Schiltknecht 2009a). Overall, the benefits of supply contracts are evident at even relatively low levels (Tang and Tomlin 2008). The quantity–flexibility contract provides value to both the buyer and supplier by reducing the trade-off between customer service level and inventory risk and is indeed useful even when a multiple-echelon SC is considered instead of dyads (Kim et al. 2013). However, other studies (Benaroch et al. 2010) have showed that it is not only the usage—i.e. quantity—but also the different sourcing options and pricing models by which the buyer could be offered flexibility. There are also studies that consider the impact of risk and risk attitudes on flexibility investments finding both positive (Tomlin 2006; Reimann and Schiltknecht 2009b) and negative relationships (Zhao et al. 2013). Finally, MSCF can also be considered in conjunction with financial hedging. Product flexibilities act as a complement to financial hedging in risk mitigation, whereas postponement flexibility acts as a substitute (Chod et al. 2010).

The MSCF and agility stream suggests SC agility and MSCF are tightly interlinked. At times, these terms are also used interchangeably, thereby creating an ambiguity about their differences (Bernardes and Hanna 2009; Um 2017). Thus, a main concern has been understanding whether and how these terms differ from each other (Giachetti et al. 2003; Yang 2014; Fayezi and Zomorrodi 2015) as well as from other related concepts such as leagility (Narasimhan et al. 2006; Purvis et al. 2014). Braunscheidel and Suresh (2009) have provided clarity for agility by conceptualizing and operationalizing it as a multidimensional measure that is distinctly different from MF. Studies that aimed to delineate these two concepts consider MF to be an antecedent of agility (Swafford et al. 2006a, b; Chan et al. 2017; Um et al. 2017). While not always articulated, a competence–capability perspective is prevalent in this relationshipFootnote 2 (Chiang et al. 2012). This research line also includes studies that focus on the organizational factors that significantly affect the flexibility–agility link, usually through survey-based research, with a few exceptions based on case studies (Fayezi et al. 2015), and analytical approaches (Wadhwa et al. 2007). The most notable factor is integration, which, unlike the supplier integration discussed in value chain cluster, also accounts for customer integration as a priority for developing agility (Braunscheidel and Suresh 2009; Chiang et al. 2012; Fayezi et al. 2015). The link between integration, MSCF and agility has been extended by considering other factors including learning (Tse et al. 2016) and technology (Swafford et al. 2008).

Capability cluster (13.06%) emerges as a central research cluster; the purpose of which is to understand MSCF from various theoretical perspectives (i.e. competence–capability, dynamic capability, resource-based view or knowledge-based view theories). It is dominated by empirical studies that try to shed light on the impact that different SC competences and capabilities (Shah and Sharma 2014)—specially technology (Chen et al. 2009; Devaraj et al. 2012; Jin et al. 2014) and knowledge (Kristal et al. 2010; Blomé et al. 2014; Rojo et al. 2016)—have on firm’s responsiveness. The various theories applied in this stream and the resultant differences in conceptualization makes cross-comparison of studies difficult, yet there can be significant overlaps in the variables of interest. There is a high heterogeneity in the proposed models for exploring the impact of these SC competences and capabilities on performance. These models explore both SC competence–capability direct effect on flexibility (Kristal et al. 2010; Hall et al. 2010; Gligor 2014; Blomé et al. 2014; Rojo et al. 2016) and the mediator effect of MF on different SC competence–capability–performanceFootnote 3 relationships (Devaraj et al. 2012; Jin et al. 2014). A small number of studies have also explored the possible complementary/substitutive impact of different SC competences and capabilities (Malhotra and Mackelprang 2012).

Finally, the analysis suggests two specialization clusters: the SC planning cluster (13.97%) includes research that develops mathematical models to help the decision-making process of MSCF management. Papers in this cluster focus on capacity planning (Zhang and Tseng 2009; Chou et al. 2011; Negahban et al. 2014) or supplier selection and the optimal order allocation (Boulaksil et al. 2011), using multiple-criteria models including the analytical hierarchy or network process, genetic algorithm or fuzzy set theory. The SC purchasing practices cluster (5.85%) comprises studies explaining the role of supply management practices on creating MSCF. Particularly they investigate what specific inter-firm practices, such as multiple sourcing, inventory buffers across the supply network and/or supplier long-term relationships (Tachizawa and Thomson 2007; Tachizawa and Giménez 2010; Gosling et al. 2010), are used to achieve MSCF, individually or collectively.

Discussion and Future Directions

The themes of planning, purchasing, value chain, capability and volatility identified during the co-word analysis highlight the main areas of interest in the MSCF literature. Considering these themes through the competence–capability perspective, which was explained in the capability cluster in the previous section, can help explain how these themes—and their sub-themes earlier—cumulatively define the MSCF domain. The resulting integrative framework is introduced in Fig. 5.

The building blocks of the manufacturing and supply chain flexibility competence are the interconnected and reinforcing approaches to planning (the planning cluster), partners—in procurement (the purchasing cluster) and distribution (the distribution and MSCF sub-cluster)—the processes that build manufacturing flexibility and finally information sharing and communication (the collaboration and MSCF sub-cluster). These can be considered as the key structural and infrastructural building blocks of manufacturing and supply chain flexibility (Slack 2005a; Merschmann and Thonemann 2011; Alves Filho et al. 2015). It is worth noting that these building blocks are still predominantly considered in isolation (Li et al. 2018), providing opportunities for integrative studies (Kumar and Mishra 2017; Singh and Kumar 2017). Kumar et al. (2006) and Tiwari et al. (2015) conceptual models are good starting points in addressing this need. The strategy that supports and drives manufacturing and supply chain flexibility has received significant attention, and relevant papers were captured in our value chain cluster (the conceptualization and operationalization, and the strategic MSCF management sub-clusters) (e.g. Fantazy et al. 2009; Soon and Udin 2011; Lo 2016). The antecedents and contingencies are discussed in all clusters but particularly the MSCF and business uncertainty sub-cluster. Luo and Yu (2016) also offer an in-depth argument on contingencies approach, which could be extended further with different contingency factors in the future. Investigating several contingencies holistically is important (Simangunsong et al. 2012; Singh et al. 2017; Kumar and Mishra 2017), as most of the previous studies are fragmented and cannot help identify the more prominent, and even perhaps conflicting ones. Sanchez and Perez (2005) is an illustration of this point and should be complemented with studies outside the automotive sector. Finally, the impact of manufacturing and supply chain strategy on other supply chain factors such as sustainability (strategic MSCF management sub-cluster), risk (MSCF and risk management sub-cluster) and agility (MSCF and agility sub-cluster) has been the focus of our volatility cluster and, given the interest in those topics, is likely to continue to be addressed in future studies. It also is in alignment with the conceptualization of flexibility as a competence and a means that feeds into each of these capabilities as an end (Zhang et al. 2003; Chiang et al. 2012).

Future Research Opportunities in MSCF

Given that no single cluster appeared as a motor cluster there is still significant potential in MSCF research development. A closer look at Fig. 3 suggests that while the value chain, capability and volatility clusters all are quite central to this topic none of the clusters have reached the maturity to be considered exhaustive. The clusters are placed low on the density axis, in other words, there is a significant yet fragmented body of research. We provide some suggestions on how to move towards a more interconnected field.

One approach is to go back to the roots of flexibility; at its heart, flexibility is a coping mechanism against uncertainty. Yet, the conceptual work in the volatility cluster, on the relationship between uncertainty and MSCF, suggests that there are distinct sources of uncertainty to be explored (Simangunsong et al. 2012). These can be grouped into three: uncertainties arising from the inside the company (i.e. intra-organizational uncertainty); uncertainties arising from the supply chain (i.e. inter-organizational uncertainty/risks); and finally, external uncertainties, which are outside a company’s direct control. While the MSCF literature has investigated some of intra-organizational or external uncertainties such as those driven by business context including suppliers and customers (Nagarajan et al. 2013; Kim and Chai 2016), other types of uncertainties have received insufficient attention, including human resource management practices (Lim et al. 2010), management style (Lin 2003), business culture (Lim et al. 2012), parallel interaction, partnerships quality and dependence (Chang and Huang 2012), knowledge ambiguity (Rojo et al. 2016; Tse et al. 2016), company’s financial position (Bandaly et al. 2012), customs dues (Braunscheidel and Suresh 2009) or country legislations (Fredriksson 2014). Furthermore, these uncertainties also need to be considered in relation to each other within the context of flexibility for two reasons. First, understanding the degree of different uncertainties could be relevant in prioritizing management actions (Govindan et al. 2017). Second, although some authors have claimed that a link may exist between different sources of uncertainty and risks, and thus is necessary to understand the effect that managing one source of uncertainty could have upon another (Yi et al. 2011), there is limited empirical work (Malhotra and Mackelprang 2012; Shah and Sharma 2014). This level of understanding of the context can help managers take a focused approach to the structural and infrastructural investments in MSCF (Slack 2005b).

An alternative to this approach would be to discuss MSCF as a means (Slack 2005b). The competence–capability perspective can be particularly effective. As we discussed earlier, flexibility has been considered as a competence that helps build capabilities in risk management, sustainability, and agility (e.g. Shukla et al. 2010; Chiang et al. 2012; Bag and Gupta 2017). Yet, we understand little in the underlying mechanism, in other words the “how”. Understanding this link, through qualitative research, would also help understand how the various planning, collaboration, process and information sharing elements reinforce each other to create the right MSCF competence. Furthermore, future research can explore the relationships between risk management and agility as well sustainability (Gunasekaran et al. 2016). The potential trade-off between risk management, agility and corporate social responsibility (CSR) is relatively unexplored. There even is little work on the direct link between CSR and MSCF (Chandra et al. 2010).

Even the individual structural and infrastructural elements of MSCF still have the potential for future research. For example, opportunities exist in studying MSCF in the context of multiple suppliers or customers and even the whole SC network rather than individual dyads. In the past, internal supplier and customer integration was investigated in separate, very context-specific models, limiting a general perspective. In addition, the focus of research has been mainly on supplier integration (Chang et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2006; Omar et al. 2012; Willis et al. 2016). Future research should consider the potential interactions among internal supplier and customer integration (Wong et al. 2011). Similarly, there are to date no empirical studies that investigate how to manage parallel interactions,Footnote 4 which is acquiring special relevance in the growing context of e-business. In SC relationships where the suppliers carry out a significant portion of the work originally handled by the buying organization, such as the lead suppliers for platforms in the automotive industry, agency theory could offer a potentially important interpretive frame in understanding their impact on MSCF (Simangunsong et al. 2012).

Similarly, inter-organizational information sharing and communication systems are critical, although less studied, in the context of uncertainties, risks and MSCF (Stevenson and Spring 2009). Not to mention, there has been relatively little work on technology and knowledge transfer as additional sources of risk and uncertainty; sometimes technology solutions can increase supply chain vulnerability due to complexity and reliance, thus reducing MSCF (Simangunsong et al. 2012). At the same time, these systems enhance the process and quality of decision-making and consequently improve SC alignment and reduce SC planning complexity (Blomé et al. 2014). There is also still room to explore how firms use their current information sharing and communication technologies and exploit the advantages generated by existing partner relationships with both suppliers and customers (Jin et al. 2014). Additional gaps in this context are the challenges for SMEs to adopt some of the existing technologies, thus disadvantaging them as well as preventing the buying firm to integrate technologies across suppliers. There are still unanswered questions around the fairness in distributing the gains from using such technologies, the role of the cultural contexts in knowledge sharing in global supply chains and the effectiveness of informal versus formal knowledge sharing mechanisms in developing MSCF. Likewise, some social media technologies have been relatively ignored in MSCF literature, yet they can potentially have disruptive effects.

Apart from these gaps in content, there are additional opportunities from a methodological perspective. Quantitative studies are scarce, relatively recent and very context-specific (Tipu and Fantazy 2014; Fayezi et al. 2015; Saghiri and Barnes 2016; Lo 2016). Most of them come from emerging economies (i.e. India, Taiwan), where supply chains are still developing and decision-making structures show differences. Multi-country studies are absent except for He et al. (2014). This is surprising given that several prominent supply chains cover vast geographic areas, and therefore, synchronizing a series of interrelated activities in these distributed, global networks is a major challenge. Finally, the MSCF purchasing practices cluster was dominated by studies from Spain. However, considering that sourcing practices can differ significantly across countries, future studies could extend their samples to other geographical contexts. Furthermore, in the international context, the adoption of these practices can result in the development of different ownership and control structures in the supply chain, e.g. control shared with other members or under responsibility of the focal firm, the selection of which may be affected by other variables such as power, level of dependency or country factors that are still absent from the literature, yet are likely to have significant impact on MSCF.

In summary, the results of this review suggest that MSCF requires a carefully planned, tailored and integrated network of organizations for whom the goal is (Kumar et al. 2006, Swafford et al. 2006, Tiwari et al. 2015): (1) adaptability, which is the ability to effectively adjust the SC network design and strategy to meet structural changes in markets; (2) alignment, which focuses on creating the incentives for the individual network partners to motivate all to work together in developing MSCF; and (3) awareness, that is, the ability to identify dynamic market requirements, customer needs and business risks. The fulfilment of these three objectives helps companies establish MSCF that can support customized products and better preparedness against disruptions.

Conclusion

This study reflects on the current state of MSCF research by identifying the major themes in this field and their respective level of maturity, integrating them through a framework and suggesting future research opportunities. Our sample is composed of 222 peer-reviewed papers published during the last 2 decades. It was analysed using co-word analysis, which resulted in five thematic clusters revealing a still evolving field. The analysis was extended with a critical reflection of these themes, discussing the current state and knowledge gaps for each individually. Finally, the five clusters were discussed through an integrative framework, the relationship between the thematic clusters was explained and the main research opportunities for MSCF were identified.

Despite the academic relevance of the paper, it also aims to have practical relevance to managers focused on improving their understanding of MSCF. Managers must plan, organize and manage MSCF that is in alignment with and supportive of the organization’s strategic goals. The integrative MSCF framework can help managers to see how the various themes in this larger, fragmented research domain fit together, the synergistic effects of some decisions and in some cases the trade-offs one faces. The integrative framework allows managers to keep track of the main structural and infrastructural decisions they need to make to support MSCF. In addition, it highlights some of the enablers such as procurement to MSCF. Finally, the framework links MSCF to some very contemporary challenges in supply chain management such as agility, risk management, and sustainability. The framework can be considered a high-level roadmap to building MSCF helping managers keep track the various decisions they need to make in relation to their planning, processes, relationships, and supporting activities.

Despite these contributions, this paper is not without limitations, which provide opportunities for further research. First, this article may have ignored some relevant knowledge as it focused only on peer-reviewed, English-published articles available at the time of search. Including additional knowledge from other sources might somewhat influence the results and the conclusions drawn. Further research may include a large set of academic publications, professional magazines and/or reports.

Notes

Bullwhip effect: “the progressive increasing of upstream production variability caused by demand variability at the retail level in the chain” (Pereira 2010, p. 6358).

This perspective conceptualized SCF as an internal competence, i.e. what the organization excels at the leads to the external capability of agility, which is the organization’s ability to use its resources and processes to effectively respond to its environment dynamic needs.

Measures employed have a wide range of indicators from logistics, flexibility or delivery performance to overall firm performance.

It considers the complexity arising due to the way in which customer interacts with multiple identical suppliers (Simangunsong et al. 2012).

References

Abdelilah, B., El Korchi, A., & Balambo, M. A. (2018). Flexibility and agility: Evolution and relationship. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management,29(7), 1138–1162.

Ali, M., & Murshid, M. (2016). Performance evaluation of flexible manufacturing system under different material handling strategies. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,17(3), 287–305.

Alves Filho, A. G., Nogueira, E., & Bento, P. E. G. (2015). Operations strategies of engine assembly plants in the Brazilian automotive industry. International Journal of Operations & Production Management,35(5), 817–838.

Aprile, D., Garavelli, A., & Giannoccaro, I. (2005). Operations planning and flexibility in a supply chain. Production Planning & Control,16(1), 21–31.

Arnold, V., Benford, T., Canada, J., & Sutton, S. (2015). Leveraging integrated information systems to enhance strategic flexibility and performance: The enabling role of enterprise risk management. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems,19, 1–16.

Asmussen, J., Kristensen, J., & Wæhrens, B. (2018). Outsourcing of production: The valuation of volume flexibiltiy in decision-making. LogForum Scientific Journal of Logistics,14(1), 73–83.

Avittathur, B., & Swamidass, P. (2007). Matching plant flexibility and supplier flexibility: Lessons from small suppliers of US manufacturing plants in India. Journal of Operations Management,25(3), 717–735.

Babazadeh, R., Razmi, J., & Ghodsi, R. (2013). Facility location in responsive and flexible supply chain network design (SCND) considering outsourcing. International Journal of Operational Research,17(3), 295–310.

Bag, S., & Gupta, S. (2017). Antecedents of sustainable innovation in supplier networks: A South African experience. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,18(3), 231–250.

Bai, C., & Sarkis, J. (2013). Flexibility in reverse logistics: A framework and evaluation approach. Journal of Cleaner Production,47, 306–318.

Balakrishnan, A., & Geunes, J. (2003). Production planning with flexible product specifications: An application to specialty steel manufacturing. Operations Research,51(1), 94–112.

Bandaly, D., Satir, A., Kahyaoglu, Y., & Shanker, L. (2012). Supply chain risk management—I: Conceptualization, framework and planning process. Risk Management,14(4), 249–271.

Bandaly, D., Shanker, L., Kahyaoglu, Y., & Satir, A. (2013). Supply chain risk management—II: A review of individual and integrated operational and financial approaches. Risk Management,15(1), 1–31.

Banker, R., & Bardhan, A. (2006). Understanding the impact of collaboration software on product design and development. Information Systems Research,17(4), 352–373.

Barad, M., & Sapir, D. (2003). Flexibility in logistic systems—Modeling and performance evaluation. International Journal of Production Economics,85(2), 155–170.

Bardhan, I., Whitaker, J., & Mithas, S. (2006). Information technology, production process outsourcing, and manufacturing plant performance. Journal of Management Information Systems,23(2), 13–40.

Bassamboo, A., Randhawa, R., & Mieghem, J. (2012). A little flexibility is all you need: On the asymptotic value of flexible capacity in parallel queuing systems. Operations Research,60(6), 1423–1435.

Beach, R., Muhlemann, A., Price, D., Paterson, A., & Sharp, J. (2000). A review of manufacturing flexibility. European Journal of Operational Research,122(1), 41–57.

Benaroch, M., Dai, Q., & Kauffman, R. (2010). Should we go our own way? Backsourcing flexibility in IT services contracts. Journal of Management Information Systems,26(4), 317–358.

Benavides-Velasco, C., Quintana-García, C., & Guzmán-Parra, V. (2013). Trends in family business research. Small Business Economics,40(1), 41–57.

Bernardes, E., & Hanna, M. (2009). A theoretical review of flexibility, agility and responsiveness in the operations management literature: Toward a conceptual definition of customer responsiveness. International Journal of Operations & Production Management,29(1), 30–53.

Bish, E., Muriel, A., & Biller, S. (2005). Managing flexible capacity in a make-to-order environment. Management Science,51(2), 167–180.

Bish, E., & Wang, Q. (2004). Optimal investment strategies for flexible resources, considering pricing and correlated demands. Operations Research,52(6), 954–964.

Blomé, C., Schoenherr, T., & Rexhausen, D. (2013). Antecedents and enablers of supply chain agility and its effect on performance: a dynamic capabilities perspective. International Journal of Production Research, 51(4), 1295–1318.

Blomé, C., Schoenherr, T., & Eckstein, D. (2014). The impact of knowledge transfer and complexity on supply chain flexibility: A knowledge-based view. International Journal of Production Economics,147, 307–316.

Bloss, D., & Pillai, D. (2001). E-manufacturing opportunities in semiconductor processing. Semiconductor International,24(8), 88–96.

Boonlua, S., & Photong, L. (2012). Comparative study of supply chain development in Thai and Malaysian firms. Journal of International Business Strategy,12(1), 30–38.

Boulaksil, Y., Grunow, M., & Fransoo, J. (2011). Capacity flexibility allocation in an outsourced supply chain with reservation. International Journal of Production Economics,129(1), 111–118.

Braunscheidel, M., & Suresh, N. (2009). The organizational antecedents of a firm’s supply chain agility for risk mitigation and response. Journal of Operations Management,27(2), 119–140.

Brozovic, D. (2018). Strategic flexibility: A review of the literature. International Journal of Management Reviews,20(1), 3–31.

Cachon, G., & Olivares, M. (2010). Drivers of finished-goods inventory in the US automobile industry. Management Science,56(1), 202–216.

Callon, M., Penan, H., & Courtial, J. (1995). Cienciometría: la medición de la actividad científica: de la bibliometría a la vigilancia tecnológica. Trea editions.

Calma, A., Martí-Parreño, J., & Davies, M. (2019). Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 1973–2018: An analytical retrospective. Scientometrics,119(2), 879–908.

Calvo, R., Domingo, R., & Rubio, E. (2006). A heuristic approach for decision-making on assembly systems for mass customization. Materials Science Forum,526, 1–6.

Calvo, R., Domingo, R., & Sebastián, M. (2007). Operational flexibility quantification in a make-to-order assembly system. International Journal of Flexible Manufacturing Systems,19(3), 247–263.

Candace, Y., Ngai, E., & Moon, K. (2011). Supply chain flexibility in an uncertain environment: Exploratory findings from five case studies. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal,16(4), 271–283.

Chambost, V., & Stuart, P. (2007). Selecting the most appropriate products for the forest biorefinery. Industrial Biotechnology,3(2), 112–119.

Chan, F., Bhagwat, R., & Wadhwa, S. (2009). Study on suppliers’ flexibility in supply chains: Is real-time control necessary? International Journal of Production Research,47(4), 965–987.

Chan, A., Ngai, E., & Moon, K. (2017). The effects of strategic and manufacturing flexibilities and supply chain agility on firm performance in the fashion industry. European Journal of Operational Research,259(2), 486–499.

Chandra, A., Deshmukh, S., & Kanda, A. (2010). Flexibility and sustainability of supply chains: Are they together? Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,11(1–2), 25–38.

Chang, S., Chen, R., Lin, R., Tien, S., & Sheu, C. (2006). Supplier involvement and manufacturing flexibility. Technovation,26(10), 1136–1146.

Chang, K., & Huang, H. (2012). Using influence strategies to advance supplier delivery flexibility: The moderating roles of trust and shared vision. Industrial Marketing Management,41(5), 849–860.

Chatzikontidou, A., Longinidis, P., Tsiakis, P., & Georgiadis, M. (2017). Flexible supply chain network design under uncertainty. Chemical Engineering Research and Design,128, 290–305.

Chaudhuri, A., Boer, H., & Taran, Y. (2018). Supply chain integration, risk management and manufacturing flexibility. International Journal of Operations & Production Management,38(3), 690–712.

Chen, M., Wang, S., & Chiou, C. (2009). The e-business policy of global logistics management for manufacturing. International Journal of Electronic Business Management,7(2), 86–97.

Chiang, C., Kocabasoglu-Hillmer, C., & Suresh, N. (2012). An empirical investigation of the impact of strategic sourcing and flexibility on firm’s supply chain agility. International Journal of Operations & Production Management,32(1), 49–78.

Chirra, S., & Kumar, D. (2018). Evaluation of supply chain flexibility in automobile industry with fuzzy DEMATEL approach. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,19(4), 305–319.

Chod, J., Rudi, N., & Van-Mieghem, J. (2010). Operational flexibility and financial hedging: Complements or substitutes? Management Science,56(6), 1030–1045.

Chou, C., Chua, G., Teo, C., & Zheng, H. (2010). Design for process flexibility: Efficiency of the long chain and sparse structure. Operations Research,58(1), 43–58.

Chou, C., Geoffrey, A., Chung-Piaw, T., & Zheng, H. (2011). Process flexibility revisited: The graph expander and its applications. Operations Research,59(5), 1090–1105.

Chu, Y., Chang, K., & Huang, F. (2011). The role of social mechanisms in promoting supplier flexibility. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing,18(2), 155–187.

Chu, Y., Chang, K., & Huang, F. (2012). How to increase supplier flexibility through social mechanisms and influence strategies? Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing,27(2), 115–131.

Clyde, E. (1999). Palletizing unit loads: Many options. Material Handling Engineering,54(1), 99–106.

Cobo, M., López-Herrera, A., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2011). An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the fuzzy sets theory field. Journal of Informetrics,5(1), 146–166.

Coronado, M., & Lyons, A. (2007). Evaluating operations flexibility in industrial supply chains to support build-to-order initiatives. Business Process Management Journal,13(4), 572–587.

Correll, D., Suzuki, Y., & Martens, B. (2014). Biorenewable fuels at the intersection of product and process flexibility: A novel modeling approach and application. International Journal of Production Economics,150, 1–8.

Coulter, N., Monarch, I., & Konda, S. (1998). Software engineering as seen through its research literature: A study in co-word analysis. Journal of the American Society of Information Sciences,49(13), 1206–1223.

Cucchiella, F., Gastaldi, M., & Koh, S. (2010). Performance improvement: An active life cycle product management. International Journal of Systems Science,41(3), 301–313.

Cvsa, V., & Gilbert, S. (2002). Strategic commitment versus postponement in a two-tier supply chain. European Journal of Operational Research,141(3), 526–543.

Dabhilkar, M., & Bengtsson, L. (2008). Invest or divest? On the relative improvement potential in outsourcing manufacturing. Production Planning and Control,19(3), 212–228.

Dabhilkar, M., Bengtsson, L., Von Haartman, R., & Åhlström, P. (2009). Supplier selection or collaboration? Determining factors of performance improvement when outsourcing manufacturing. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management,15(3), 143–153.

Dansereau, L., El-Halwagi, M., Mansoornejad, B., & Stuart, P. (2014). Framework for margins-based planning: Forest biorefinery case study. Computers & Chemical Engineering,63, 34–50.

Dansereau, L., El-Halwagi, M., & Stuart, P. (2012). Value-chain planning in the forest biorefinery: Case study analyzing manufacturing flexibility. J-for-Journal of Science & Technology for Forest Products and Processes,2(4), 60–69.

Das, K. (2011). Integrating effective flexibility measures into a strategic supply chain planning model. European Journal of Operational Research,211(1), 170–183.

Dauzère-Pérès, S., Nordli, A., Olstad, A., Haugen, K., Koester, U., Per Olav, M., et al. (2007). Omya Hustadmarmor optimizes its supply chain for delivering calcium carbonate slurry to European paper manufacturers. Interfaces,37(1), 39–51.

De Giovanni, D., & Massabò, I. (2018). Capacity investment under uncertainty: The effect of volume flexibility. International Journal of Production Economics,198, 165–176.

Devaraj, S., Vaidyanathan, G., & Mishra, A. (2012). Effect of purchase volume flexibility and purchase mix flexibility on e-procurement performance: An analysis of two perspectives. Journal of Operations Management,30(7), 509–520.

Dey, S., Sharma, R. R. K., & Pandey, B. K. (2019). Relationship of manufacturing flexibility with organizational strategy. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 20(3), 237–256.

Di Stefano, G., Peteraf, M., & Verona, G. (2010). Dynamic capabilities deconstructed: A bibliographic investigation into the origins, development, and future directions of the research domain. Industrial and Corporate Change,19(4), 1187–1204.

Duclos, L., Vokurka, R., & Lummus, R. (2003). A conceptual model of supply chain flexibility. Industrial Management & Data Systems,103(6), 446–456.

Dulluri, S., & Srinivasa, N. (2009). Stochastic operational planning model for production and distribution in a hi-tech manufacturing network. International Journal of Operational Research,5(2), 163–189.

Durach, C., Kembro, J., & Wieland, A. (2017). A new paradigm for systematic literature reviews in supply chain management. Journal of Supply Chain Management,53(4), 67–85.

Dwaikat, N., Money, H., Behashti, H., & Salehi-Sangari, E. (2018). How does information sharing affect first-tier suppliers’ flexibility? Evidence from the automotive industry in Sweden. Production Planning & Control,29(4), 289–300.

Engelhardt-Nowitzki, C. (2012). Improving value chain flexibility and adaptability in build-to-order environments. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management,42(4), 318–337.

Esmaeilikia, M., Fahimnia, B., Sarkis, J., Govindan, K., Kumar, A., & Mo, J. (2016). Tactical supply chain planning models with inherent flexibility: Definition and review. Annals of Operations Research,244(2), 407–427.

Fahimnia, B., Sarkis, J., & Davarzani, H. (2015). Green supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Production Economics,162, 101–114.

Fantazy, K., Kumar, V., & Kumar, U. (2009). An empirical study of the relationships among strategy, flexibility, and performance in the supply chain context. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal,14(3), 177–188.

Fantazy, K., & Salem, M. (2016). The value of strategy and flexibility in new product development. Journal of Enterprise Information Management,29(4), 525–548.

Fayezi, S., & Zomorrodi, M. (2015). The role of relationship integration in supply chain agility and flexibility development: An Australian perspective. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management,26(8), 1126–1157.

Fayezi, S., Zutshi, A., & O’Loughlin, A. (2014). Developing an analytical framework to assess the uncertainty and flexibility mismatches across the supply chain. Business Process Management Journal,20(3), 362–391.

Fayezi, S., Zutshi, A., & O’Loughlin, A. (2015). How Australian manufacturing firms perceive and understand the concepts of agility and flexibility in the supply chain. International Journal of Operations & Production Management,35(2), 246–281.

Fayezi, S., Zutshi, A., & O’Loughlin, A. (2017). Understanding and development of supply chain agility and flexibility: A structured literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews,19(4), 379–407.

Feng, Y., Zhu, Q., & Lai, K. (2017). Corporate social responsibility for supply chain management: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production,158, 296–307.

Ferdows, K., & Carabetta, C. (2006). The effect of inter-factory linkage flexibility on inventories and backlogs in integrated process industries. International Journal of Production Research,44(2), 237–255.

Foo, D., Tan, R., Lam, H., Aziz, M., & Klemeš, J. (2013). Robust models for the synthesis of flexible palm oil-based regional bioenergy supply chain. Energy,55, 68–73.

Francas, D., & Minner, S. (2009). Manufacturing network configuration in supply chains with product recovery. Omega,37(4), 757–769.

Fredriksson, A. (2014). Manufacturing and supply chain flexibility—Towards a tool to analyse production network coordination at operational level. Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal,7(2), 173–194.

Garavelli, A. (2003). Flexibility configurations for the supply chain management. International Journal of Production Economics,85(2), 141–153.

Giachetti, R., Martinez, L., Sáenz, O., & Chen, C. (2003). Analysis of the structural measures of flexibility and agility using a measurement theoretical framework. International Journal of Production Economics,86(1), 47–62.

Gligor, D. (2014). A cross-disciplinary examination of firm orientations’ performance outcomes: The role of supply chain flexibility. Journal of Business Logistics,35(4), 281–298.

Gligor, D., & Holcomb, M. (2012). Understanding the role of logistics capabilities in achieving supply chain agility: A systematic literature review. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal,17(4), 438–453.

Goldsby, T., & García-Dastugue, S. (2003). The manufacturing flow management process. The International Journal of Logistics Management,14(2), 33–52.

Gosling, J., Naim, M., & Towill, D. (2013). A supply chain flexibility framework for engineer-to-order systems. Production Planning & Control,24(7), 552–566.

Gosling, J., Purvis, L., & Naim, M. (2010). Supply chain flexibility as a determinant of supplier selection. International Journal of Production Economics,128(1), 11–21.

Govindan, K., Fattahi, M., & Keyvanshokooh, E. (2017). Supply chain network design under uncertainty: A comprehensive review and future research directions. European Journal of Operational Research,263(1), 108–141.

Govindarajulu, N., & Daily, B. (2009). Exploring the antecedents of externally-driven flexibilities. Journal of Management Research,9(2), 83.

Grawe, S., Daugherty, P., & Roath, A. (2011). Knowledge synthesis and innovative logistics processes: Enhancing operational flexibility and performance. Journal of Business Logistics,32(1), 69–80.

Grover, P., & Kar, A. K. (2017). Big data analytics: A review on theoretical contributions and tools used in literature. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,18(3), 203–229.

Gunasekaran, A., Dubey, R., & Singh, S. P. (2016). Flexible sustainable supply chain network design: Current trends, opportunities and future. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,17(2), 109–112.

Gunasekaran, A., & McGaughey, R. (2003). TQM is supply chain management. The TQM Magazine,15(6), 361–363.

Hall, D., Skipper, J., & Hanna, J. (2010). The mediating effect of comprehensive contingency planning on supply chain organisational flexibility. International Journal of Logistics: Research and Applications,13(4), 291–312.

Han, J., Wang, Y., & Naim, M. (2017). Reconceptualization of information technology flexibility for supply chain management: An empirical study. International Journal of Production Economics,187, 196–215.

Harkonen, J., Haapasalo, H., & Hanninen, K. (2015). Productisation: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Production Economics,164, 65–82.

Hasuike, T., & Ishii, H. (2009). On flexible product-mix decision problems under randomness and fuzziness. Omega,37(4), 770–787.

Hayes, R., & Wheelwright, S. (1984). Restoring our competitive edge: Competing through manufacturing. New York, NY: Wiley.

He, Y., Kin, K., Hongyi, S., & Chen, Y. (2014). The impact of supplier integration on customer integration and new product performance: The mediating role of manufacturing flexibility under trust theory. International Journal of Production Economics,147, 260–270.

Holweg, M. (2005). The three dimensions of responsiveness. International Journal of Operations & Production Management,25(7), 603–622.

Huchzermeier, A., & Cohen, M. (1996). Valuing operational flexibility under exchange rate risk. Operations Research,44(1), 100–113.

Indranil, B., Demirkan, H., Kannan, P., Kauffman, R., & Sougstad, R. (2010). An interdisciplinary perspective on IT services management and service science. Journal of Management Information Systems,26(4), 13–64.

Ishfaq, R. (2013). Intermodal shipments as recourse in logistics disruptions. Journal of the Operational Research Society,64(2), 229–240.

Jain, A. (2018). Responding to shipment delays: The roles of operational flexibility & lead-time visibility. Decision Sciences,49(2), 306–334.

Jain, A., Jain, P., Chan, F., & Singh, S. (2013). A review on manufacturing flexibility. International Journal of Production Research,51(19), 5946–5970.

Jin, Y., Vonderembse, M., Ragu-Nathan, T., & Smith, J. (2014). Exploring relationships among IT-enabled sharing capability, supply chain flexibility, and competitive performance. International Journal of Production Economics,153, 24–34.

Jitpaiboon, T., & Sharma, S. (2013). Comparative study of supply chain relationships, mass customization, and organizational performance between SME(s) and LE(s). Journal of Business Administration Research,1(2), 139–157.

Kara, S., Kayis, B., & O’Kane, S. (2002). The role of human factors in flexibility management: A survey. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries,12(1), 75–119.

Karrenbauer, J. (2012). Transforming the supply chain: Steps for understanding and reworking your entire network. Materials Management and Distribution,57(3), 22–23.

Kaur, S. P., Kumar, J., & Kumar, R. (2017). The relationship between flexibility of manufacturing system components, competitiveness of SMEs and business performance: A study of manufacturing SMEs in Northern India. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,18(2), 123–137.

Kavitha, C., & Vijayalakshmi, C. (2013a). Implementation of fuzzy multi objective linear programming for decision making and planning under uncertainty. Indian Journal of Computer Science and Engineering,4(2), 103–121.

Kavitha, C., & Vijayalakshmi, C. (2013b). Implementation of supplier evaluation and ranking by improved TOPSIS. Applied Mathematical Sciences,7(46), 2265–2270.

Kavitha, C., & Vijayalakshmi, C. (2015). Fuzzy multi objective mixed integer linear programming technique for supply chain management. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics,101(5), 781–790.

Kayis, B., & Kara, S. (2005). The supplier and customer contribution to manufacturing flexibility: Australian manufacturing industry’s perspective. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management,16(7), 733–752.

Kazaz, B., Dada, M., & Moskowitz, H. (2005). Global production planning under exchange-rate uncertainty. Management Science,51(7), 1101–1119.

Kazemian, I., & Aref, S. (2016). Multi-echelon supply chain flexibility enhancement through detecting bottlenecks. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,17(4), 357–372.

Kemmoe, S., Pernot, P., & Tchernev, N. (2014). Model for flexibility evaluation in manufacturing network strategic planning. International Journal of Production Research,52(15), 4396–4411.

Keong, O., Ahmad, M., Ismail, S., Sulaiman, N., & Yusuf, M. (2005). Proposing a non-traditional ordering methodology in achieving optimal flexibility with minimal inventory risk. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics,17(2), 31–43.

Kesen, S. (2014). Capacity-constrained supplier selection model with lost sales under stochastic demand behaviour. Neural Computing and Applications,24(2), 347–356.

Kim, W. (2011). Order quantity flexibility as a form of customer service in a supply chain contract model. Flexible Services and Manufacturing Journal,23(3), 290–315.

Kim, M., & Chai, S. (2016). Assessing the impact of business uncertainty on supply chain integration. The International Journal of Logistics Management,27(2), 463–485.

Kim, M., Suresh, N., & Kocabasoglu-Hillmer, C. (2013). An impact of manufacturing flexibility and technological dimensions of manufacturing strategy on improving supply chain responsiveness: Business environment perspective. International Journal of Production Research,51(18), 5597–5611.

Klueber, R., & O’Keefe, R. (2013). Defining and assessing requisite supply chain visibility in regulated industries. Journal of Enterprise Information Management,26(3), 295–315.

Koste, L., Malhotra, M., & Sharma, S. (2004). Measuring dimensions of manufacturing flexibility. Journal of Operations Management,22(2), 171–196.

Krajewski, L., Wei, J., & Tang, L. (2005). Responding to schedule changes in build-to-order supply chains. Journal of Operations Management,23(5), 452–469.

Kristal, M., Huang, X., & Roth, A. (2010). The effect of an ambidextrous supply chain strategy on combinative competitive capabilities and business performance. Journal of Operations Management,28(5), 415–429.

Kulkarni, S., & Francas, D. (2018). Capacity investment and the value of operational flexibility in manufacturing systems with product blending. International Journal of Production Research,56(10), 3563–3589.

Kumar, R. (2019). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners. London: Sage Publications Limited.

Kumar, P., & Deshmukh, S. G. (2006). A model for flexible supply chain through flexible manufacturing. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,7(3/4), 17–24.

Kumar, V., Fantazy, K. A., Kumar, U., & Boyle, T. (2006). Implementation and management framework for supply chain flexibility. Journal of Enterprise Information Management,19(3), 303–319.

Kumar, R., & Mishra, M. (2017). Manufacturing and supply chain flexibility: An integrated viewpoint. International Journal of Services and Operations Management,27(3), 384–407.

Kumar, A., Pal, A., Vohra, A., Gupta, S., Manchanda, S., & Dash, M. (2018). Construction of capital procurement decision making models to optimize supplier selection using Fuzzy Delphi and AHP-DEMATEL. Benchmarking: An International Journal,25(5), 1528–1547.

Kumar, R., Singh, R. K., & Shankar, R. (2013). Study on coordination issues for flexibility in supply chain of SMEs: A case study. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,14(2), 81–92.

Kume, K., & Fujiwara, T. (2016). Production flexibility of real options in daily supply chain. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,17(3), 249–264.

Lagoudis, I., Naim, M., & Potter, A. (2010). Strategic flexibility choices in the ocean transportation industry. International Journal of Shipping and Transport Logistics,2(2), 187–205.

Lee, Y., & Kincade, D. H. (2003). US apparel manufacturers’ company characteristic differences based on SCM activities. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal,7(1), 31–48.

Li, Y., Guo, H., & Zhang, Y. (2018). An integrated location-inventory problem in a closed-loop supply chain with third-party logistics. International Journal of Production Research,56(10), 3462–3481.

Liao, Y., & Marsillac, E. (2015). External knowledge acquisition and innovation: The role of supply chain network-oriented flexibility and organisational awareness. International Journal of Production Research,53(18), 5437–5455.

Lim, B., Ling, F., Ibbs, C., Raphael, B., & Ofori, G. (2010). Empirical analysis of the determinants of organizational flexibility in the construction business. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management,137(3), 225–237.

Lim, B., Ling, F., Ibbs, C., Raphael, B., & Ofori, G. (2012). Mathematical models for predicting organizational flexibility of construction firms in Singapore. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management,138(3), 361–375.

Lin, B. (2003). Cooperating for supply chain effectiveness: Manufacturing strategy for Chinese OEMs. International Journal of Manufacturing Technology and Management,5(3), 232–245.

Ling-yee, L., & Ogunmokun, G. (2008). An empirical study of manufacturing flexibility of exporting firms in China: How do strategic and organizational contexts matter? Industrial Marketing Management,37(6), 738–751.

Lo, S. (2016). The influence of variability and strategy of service supply chains on performance. Service Business,10(2), 393–421.

López-Fernández, M. C., Serrano-Bedia, A. M., & Pérez-Pérez, M. (2016). Entrepreneurship and family firm research: A bibliometric analysis of an emerging field. Journal of Small Business Management,54(2), 622–639.

Lummus, R., Duclos, L., & Vokurka, R. (2003). Supply chain flexibility: Building a new model. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management,4(4), 1–14.

Lummus, R., Vokurka, R., & Duclos, L. (2005). Delphi study on supply chain flexibility. International Journal of Production Research,43(13), 2687–2708.

Lummus, R., Vokurka, R., & Duclos, L. (2006). The produce-process matrix revisited: Integrating supply chain trade-offs. SAM Advanced Management Journal,71(2), 4–12.

Luo, B. N., & Yu, K. (2016). Fits and misfits of supply chain flexibility to environmental uncertainty: Two types of asymmetric effects on performance. The International Journal of Logistics Management,27(3), 862–885.

Maestrini, V., Luzzini, D., Maccarrone, P., & Caniato, F. (2017). Supply chain performance measurement systems: A systematic review and research agenda. International Journal of Production Economics,183, 299–315.

Malhotra, K., & Mackelprang, A. (2012). Are internal manufacturing and external supply chain flexibilities complementary capabilities? Journal of Operations Management,30(3), 180–200.

Manders, J., Caniëls, M., & Paul, W. (2016). Exploring supply chain flexibility in a FMCG food supply chain. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management,22(3), 181–195.

Mansoornejad, B., Chambost, V., & Stuart, P. (2010). Integrating product portfolio design and supply chain design for the forest biorefinery. Computers & Chemical Engineering,34(9), 1497–1506.

Manuj, I., & Sahin, F. (2011). A model of supply chain and supply chain decision-making complexity. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management,41(5), 511–549.