Abstract

Victimization can harm youth in various ways and negatively affect their friendships with peers. Nevertheless, not all victimized youth are impacted similarly, and the literature is unclear regarding why some victims are more likely than others to experience friendship-based consequences. Using five waves of data on 901 adolescents (6th grade at wave 1; 47% male; 88% White) and a subsample of 492 victimized youth, this study assessed (1) whether victimization leads to decreases in perceived friend support, and (2) the factors that explain which victimized youth are most likely to experience decreases in perceived friend support. Explanatory factors included subsequent victimization, victims’ social network status (self-reported number of friends, number of friendship nominations received), and victims’ risky behaviors (affiliating with deviant friends, delinquency, aggression, binge drinking). Random effects regressions revealed that, among the full sample, victimization was linked to decreases in friend support. Among victimized youth, subsequent victimization and deviant friends decreased friend support. Having more friends was associated with increased friend support among victims, though this association weakened as the number of friends increased. The results emphasize that victimized youth are a heterogeneous group with varying risks of experiencing friendship-based consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

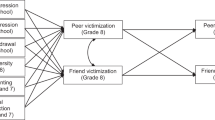

Adolescent victimization has been linked to many developmental harms. Of particular concern is the negative impact that victimization can have on youth’s social relationships—namely on their friendships and social standing among peers. Research shows that adolescent victims lose friends (Wallace & Ménard, 2017), experience peer rejection and avoidance by others (Turanovic & Young, 2016), occupy a lesser status within their peer groups (Tomlinson et al., 2021), and perceive a lack of social support from peers (Shaheen et al., 2019). Nevertheless, not all victims experience these negative peer-based consequences (Swirsky & Xie, 2021). Some adolescent victims are able to retain the support of their friends, yet the literature is unclear regarding for whom losses in support are most likely to occur after victimization. Accordingly, in this study, focus is placed on a subsample of youth who experienced victimization to identify factors that are linked to within-person changes in their perceived friend support over time. Attention is directed toward three broad factors that theory and research suggest can explain why some victims are more (or less) likely to experience decreases in perceived support: (1) victims’ status in their friendship networks (i.e., self-reported number of friends, number of friendship nominations received), (2) the degree to which victims engage in risky behaviors (i.e., affiliating with deviant friends, engaging in delinquency, aggression, or binge drinking), and (3) subsequent victimization. In carrying out this research, the goals are to better understand the conditions under which victimization produces negative peer consequences for youth, and to identify adolescent victims most in need of support services.

Friendships and Victimization in Adolescence

Adolescence is one of the most influential periods of human development—one marked by rapid physical, emotional, and social change (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). As youth transition out of childhood, they begin to establish more independence from their parents and friends start to play a central role in their lives. More so than before, adolescent friendships provide youth with support, companionship, and a sense of belonging—all of which can encourage and reinforce healthy behaviors that help youth stay resilient in the face of hardships. Friendships are important during times of difficulty, and youth without supportive ties to peers are more likely to suffer health, psychological, and behavioral problems—especially in response to events like victimization (Cooley et al., 2015). Without peer support, the harms of victimization may be magnified over time and adversely affect life outcomes.

Generally speaking, adolescent victims tend not to have access to strong, supportive friendships. While exceptions exist (e.g., Malamut et al., 2021, 2022), studies have found that victims are often disliked and rejected by their peers, and that youth are unlikely to come to the aid of victims (Graham & Juvonen, 2001). Attributional research shows that adolescents are not always sympathetic toward their victimized peers, and that they perceive victims are targeted because they deserve it—especially if their behaviors are annoying or provoking to others. For example, in their study of middle school students, Graham and Juvonen (2001, p. 59) found that most youth had victim-blaming attitudes, and that they “endorsed the belief that peers are picked on because of behavior within their control—that is, they show off, tattle-tale, or bad-mouth others.”

Victimization can also carry a social stigma in adolescence (Graham, 2016), and victims are often perceived to be of lower standing in their peer groups (Forsberg & Thornberg, 2016). Teenagers place value on peer status, and when choosing friends, they tend to gravitate toward those who are more popular and “cool” (Dijkstra et al., 2013). Existing work shows that adolescents tend to avoid victims as friends (Turanovic & Young, 2016), and that youth sometimes break off their ties to victims as a means of preserving their standing in the social network (Sentse et al., 2013). Youth may be concerned that, by being friends with victims, they too may be targeted, harassed, or otherwise stigmatized by peers (Boulton, 2013). In attempts to dodge this stigma, victims are avoided and rejected as friends—potentially leaving them to experience perceived losses in support.

Further, adolescent victims may lack the social skills necessary to gain support from others. Youth who are victimized are more likely to suffer impulse control problems (Pratt et al., 2014), depressive symptoms, and social anxiety (La Greca et al., 2016)—all of which can hinder the ability to sustain strong friendships. For instance, depressed or anxious youth tend to excessively seek reassurance from peers and negatively dwell on or ruminate about events (Borelli & Prinstein, 2006). Youth who are more impulsive also tend to be less considerate, more reactive, and hostile toward others (Evans et al., 2015)—qualities that tend to repel, rather than attract, supportive friends. Youth without supportive friendships also tend to lack support in other areas of their life, such as in their relationships with parents (Cui et al., 2002), and they tend to be less engaged in school (Estell & Perdue, 2013).

On top of these problems, victimization can coincide with social withdrawal. Out of embarrassment or fear of being harmed again, some victims avoid going to school, limit their time spent with other youth, and self-select out of social activities (Hutzell & Payne, 2012). Some victims may also distance themselves from peers out of concern that their problems will be a burden, or because victimization has shaken their confidence and trust in others (Gollwitzer et al., 2015). As such, victimized youth may suffer academically (Wang et al., 2014), have less access to peers, and fewer opportunities to form strong and supportive friendships. Cross-sectional research suggests that victimized youth perceive lower levels of peer support than youth who have not been victimized (e.g., Holt & Espelage, 2007), but the longitudinal impact of victimization on friend support has been understudied. Establishing this relationship longitudinally while accounting for known confounding factors (e.g., demographic, school, and family characteristics) is a necessary step in this line of work.

Variation in the Link between Victimization and Perceived Friend Support

Taken together, the literature suggests that victimization in adolescence can decrease levels of perceived friend support. However, not all victims are likely to suffer the same friendship-based consequences to the same degree. Thus far, research has focused largely on establishing whether an overall statistical association exists between victimization and perceptions of support among youth. Yet adolescent victims are a markedly heterogenous group (Turanovic, 2019), and there is meaningful variation to be explored in the outcomes that they experience (Malamut et al., 2022). Here the focus is on three potential factors that may explain why some victims are more likely than others to experience decreases in perceived friend support: victims’ status in friendship networks, their involvement in risky behaviors, and experiences with repeat victimization. These are also factors that can be targeted in school-based interventions for adolescent victims.

With respect to friendship network status, it is possible that victims with a higher social standing—those who report having more friends and who receive more friendship nominations from their peers—will be buffered from losses in peer support. Growing research indicates that victimization is not always limited to socially rejected, unpopular, or disliked youth (Dawes & Malamut, 2020), and that youth at the top of the status hierarchy can also be attractive targets for victimization (Malamut et al., 2021). Such youth may have a peer network expansive enough that other peers can “take up the slack” and provide support after victimization, even if some friendship losses are incurred (Stanton-Salazar & Spina, 2005, p. 409). In such circumstances, the burden of support is unlikely to fall on just one person, which can strain the friendship. More popular youth may also have more social resources to stand up to aggressors (Dawes & Malamut, 2020), and their perpetrators may be more readily vilified by the broader peer group, preventing losses in perceived friend support. In contrast, victimized youth who have a lower social standing or who are on the fringes of peer groups may not have many candidates who are willing to provide support or fill friendship voids. This may be especially true if potential friends are preoccupied with their own traumas, given that victimization is common among youth who are already socially marginalized (Graham, 2016).

Still, some research shows that higher status youth experience greater distress and social exclusion after victimization (Faris & Felmlee, 2014). In competitive social hierarchies, aggression can be a tool used to gain prestige—specifically when the target is someone higher up on the social ladder (Malamut et al., 2020). During early to mid-adolescence in particular, high-status youth tend to have fragile social positions that can be brought down by bullying and harassment (Dawes & Malamut, 2020). These youth may have “more to lose” by being victimized, or have more rivals in their friendship group who turn on them to increase their own social standing (Faris & Felmlee, 2014). Thus, an alternate possibility is that a higher social network status is not protective, but instead, that losses in peer support will be magnified among high-status victims. Either way, network status remains important to explore as a potential source of variation in changes to friend support following victimization.

Risky behavior is another factor that may help explain why some victimized youth are at greater risk of losing the support of their friends. More so than at other stages in the life course, in adolescence, peer group acceptance and social capital are facilitated by participation in risky activities. Such behaviors can include binge drinking, delinquency, acting aggressively toward others, and hanging around people who break the law. Several studies suggest that youth binge drink and participate in delinquent behaviors to “fit in” and bond with other peers (Gommans et al., 2017), and that the desire to be well-liked corresponds with aggression and deviance (Dumas et al., 2019). Research also shows that alcohol use is more common among youth who have a higher social status, including victimized youth (Malamut et al., 2022). It is possible, therefore, that youth who engage in risky behaviors are less likely to lose the support of their friends after victimization.

Of course, another possibility is that such youth are at greater risk for losses in support—particularly if their friends also engage in deviance. Because delinquent peers tend to be more self-centered and to have weaker social skills (Smångs, 2010), and because they are likely to be perpetrators of victimization themselves (Schreck et al., 2004), they may be unable or unwilling to provide warmth or support to their victimized friends. Peers may also perceive youth as contributing to their own victimization if they engage in risky activities or hang around delinquent others, and provide less sympathy or support (Graham & Juvonen, 2001). Indeed, there is much to clarify regarding how risky behavior affects perceived friend support after victimization.

Lastly, the support that victims receive can additionally be affected by their prior victimization experiences. To be sure, youth who have been victimized in the past may not receive the same degree of friend support after each subsequent victimization. Although little research has examined the effect of recurring victimization on friend support specifically, related work suggests that repeated victimization can weaken social ties, wear down others’ willingness to provide assistance, and gradually deplete support resources (Turanovic, 2018). For instance, youth who suffer recurring victimization are known to develop hostile attitudes (Yeung & Leadbeater, 2007), emotional dysregulation, and social avoidance problems (Randa et al., 2019). Recurrent victims are also at heightened risk of developing low self-esteem, depression, and other internalizing symptoms (Esbensen & Carson, 2009). These issues may ultimately strain friendships, increase social withdrawal, and lead to peer rejection. As such, subsequent victimization may be another factor that affects the amount of support victims receive from friends.

Current Study

Despite the salience of both victimization and peer support to youth development, there is much to clarify regarding how victimization impacts perceived support from friends, as well as the conditions under which losses in friend support are most likely to occur for victimized youth. Victims who perceive themselves to be without friend support may lack an important source of resiliency and be especially vulnerable to the developmental harms of victimization. To address these issues, the current study identifies the factors that explain changes (increases or decreases) in perceived friend support among youth who were victimized in early adolescence. Focus is placed specifically on network status (self-reported number of friends, number of friendship nominations received), risky behavior (affiliating with deviant friends, delinquency, aggression, and binge drinking), and subsequent victimization as sources of variability in perceived friend support among victims. It is expected that subsequent victimization will reduce perceived friend support, but it is unclear whether social network status or risky behaviors will increase or decrease friend support among victimized youth. For social network status in particular, it is possible that increases in victims’ status will increase friend support at low to moderate status levels, but decrease friend support at high status levels.

The study is carried out in two phases. First, using longitudinal data on youth from the PROmoting School-community-university Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) study, it is determined whether victimization is linked to decreases in perceived friend support, as expected from prior research. This first phase relies on data from the full analytic sample to determine the overall association between victimization and changes in perceived friend support, net of controls. Second, given that the study is focused primarily on victimized youth, the next phase determines whether network status, risky behavior, and subsequent victimization explain changes in perceived friend support among a subsample of youth who reported victimization during the first wave of the study. To strengthen inferences in each phase of the analysis, controls for demographic characteristics (sex, race/ethnicity), school factors (grades), and family factors (parent-child affective quality, family structure) are included, given their documented associations with friend support (Cui et al., 2002) and victimization (Wang et al., 2014).

Methods

Data

PROSPER is a longitudinal survey and social network study of adolescents in 28 school districts in Pennsylvania and Iowa (Spoth et al., 2004). PROSPER included school districts that enrolled between 1,300 and 5,200 students, and had student populations with at least 15% of families eligible for free or reduced cost school lunch. PROSPER’s original purpose was to test a delivery system for substance use prevention programming, and half of the districts were randomly assigned to receive such programming. The intervention condition was not significantly correlated with this study’s focal predictor (victimization) or the outcome (friend support), and was a time-stable factor for all but 8 respondents in the data (and thus was not a potential source of spuriousness). Accordingly, data from both conditions were used and intervention condition was not included in the models.

PROSPER sampled two successive cohorts of students who completed baseline in-school surveys in the fall of 6th grade (in 2002 and 2003) and follow-up surveys each spring from 6th through 12th grade. These in-school surveys were the source of the social network variables. A randomly selected subset of students from the 2003 cohort was recruited to complete in-depth in-home surveys at baseline and again each spring through 9th grade. These in-home data were the source of all other variables. Of the 2,267 students recruited for the in-home surveys, 977 (43%) participated at wave 1. Prior analyses revealed that these in-home participants resembled the larger sample on factors such as demographic characteristics and substance use but were slightly less delinquent, indicating that they were at slightly lower risk for problem behavior (Fosco & Feinberg, 2015; Lippold et al., 2011).

This study used all five waves of available data from respondents who participated in at least one in-home survey and who had valid social network data at the same wave. This reduced the full sample size by 8% from the 977 wave 1 in-home respondents to 901. Item-missing data were addressed using multiple imputation. Rates of item-missing data by wave were as follows: wave 1, 10%; wave 2, 5%; wave 3, 6%; wave 4, 5%; and wave 5, 5%. Most of these missing data were due to the grades variable (missing 2% across all observations), the two parent family variable (missing 1%), and the binge drinking variable (missing 1%). The individual items comprising all study variables, plus auxiliary variables capturing marijuana use and a range of internalizing problems, were included in the imputation model.Footnote 1 Twenty imputed datasets were created and estimates were combined across them. Standard errors were calculated using Rubin’s (1987) rules.

Measures

Perceived friend support

The dependent variable, perceived friend support, was measured at each wave using eight items from a modified version of the Friendship Quality Questionnaire—Revised (Parker & Asher, 1993). Each item asked respondents to report how true in general a statement was about their friends (1 = not at all true, 5 = really true). The statements were “my friends care about me,” “my friends don’t listen to me,” “my friends stick up for me when I’m being teased,” “my friends and I get mad at each other a lot,” “I talk to my friends when I am having a problem,” “I can count on my friends when I need them,” “my friends and I argue a lot,” and “I can always count on my friends to keep promises.” The negative items were reverse coded and the items were averaged to create a continuous scale where higher scores indicated more perceived friend support (α = 0.79).

Victimization

Victimization was measured at each wave using respondent reports of how often the following things were done to them in the past two months: “pushing or shoving,” “stealing or destroying things to be mean,” and “teasing or insulting” (α = 0.71). These items were derived from the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (Solberg & Olweus, 2003) and are commonly used in studies of victimization among youth. Items were dichotomized and summed to create a variety scale indicating the number of different types of victimization the respondent experienced at a given wave (range 0–3). A variety index was chosen over a frequency scale because variety indexes are less skewed and less sensitive to high frequency items, and because they have been shown to have high concurrent validity and equal predictive validity relative to other types of frequency scales (Sweeten, 2012). Respondents who experienced any victimization at wave 1 (yes, no) were included in the victim subsample.

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the study variables. At any given wave, slightly more than half of respondents reported experiencing at least one of the types of victimization.

Social network status

Social network status was measured at each wave using two variables: self-reported number of friends and the number of friendship nominations received.

Self-reported number of friends

At each wave, respondents were asked, “how many of the young people you know, males and females, do you consider to be your close friends?” (0 = none, 6 = nine or more). This was used as the indicator of self-reported number of friends.

Friendship nominations received

The in-school surveys asked adolescents to nominate up to two best friends and five additional close friends at each wave of data. Most respondents (94%) nominated at least one friend, and the PROSPER staff was able to match over 83% of friendship nominations to students on the schools’ class rosters. Since the entire grade-level was targeted for participation in the study, these data allowed for the construction of complete within-grade school friendship networks and the counting of the number of times each adolescent was nominated as a friend by student in the same grade. Friendship nominations received was a count of the number of students who named the adolescent as a friend at that wave. Exploratory analyses revealed a linear association of nominations received with the outcome and a curvilinear association of number of friends with the outcome. Self-reported number of friends thus was expressed as a second-order polynomial.

Risky behaviors

Four measures of risky behaviors were included: friend deviance, delinquency, aggression, and binge drinking.

Friend deviance

At each wave, respondents reported how many of their close friends (1 = none of them, 5 = all of them) had “drunk beer, wine, wine coolers, or liquor,” “drunk enough beer, wine, wine coolers, or liquor to get drunk,” “purposely damaged or destroyed things that do not belong to them,” “hit someone with the idea of hurting them,” “stolen something worth less than $25,” “stolen something worth more than $25,” “used marijuana or pot,” “used illegal drugs other than marijuana,” “sniffed glue, gas, or sprays to get high,” “skipped school without an excuse,” “shoplifted something from a store,” “used a weapon or force to get money or other things from people,” and “done things at school that got them into trouble” in the past 12 months. These items were averaged to create a measure of friend deviance (α = 0.94).

Delinquency

At each wave, respondents reported the number of times that they had “taken something worth less than $25 that didn’t belong to you,” “taken something worth $25 or more that didn’t belong to you,” “taken a car or other vehicle without the owner’s permission,” “beat up someone or physically fought with someone because they made you angry,” “shoplifted something from a store,” “snatched someone’s purse or wallet without hurting him/her,” “purposely damaged or destroyed property that did not belong to you,” “broken into or tried to break into a building just for fun or to look around,” and “broken into or tried to break into a building to steal or damage something” in the past 12 months. Consistent with recommendations for scaling criminal offending (Sweeten, 2012), items were dichotomized and summed to create a variety score of delinquency (α = 0.78). These items have been used in prior research (e.g., Kreager et al., 2011), and are part of a larger assessment of conduct problems in the PROSPER data (Spoth et al., 2015).

Aggression

At each wave, respondents reported how much the following statements were like them (1 = not at all, 5 = exactly): “if someone hits me first, I let them have it,” “when someone makes a rule I don’t like, I want to break it,” “when I get mad, I say nasty things,” “when people yell at me, I yell back,” “if someone annoys me, I tell them what they think of them,” “when someone is bossy, I do the opposite of what he/she asks,” “if I have to use physical force to defend my rights, I will,” “I do whatever I have to in order to get what I want,” and “I don’t care much about what other people think or feel.” These items come from a modified version of the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (Velicer et al., 1985) and are often used to measure aggression during adolescence (Archer, 2004). The items were averaged to create a measure of aggression (α = 0.83).

Binge drinking

Respondents at each wave reported how many times in the past month they had three or more alcoholic drinks in a row. This was used as a measure of binge drinking.

Control variables

The control variables included wave of data collection and the demographic variables male gender (0 = female, 1 = male); race/ethnicity (0 = Hispanic, African American, Asian, Native American, or other non-White race, 1 = White), and two parent family (0 = other family structure, 1 = two-parent family). Parent-child affective quality was constructed at each wave from items that asked respondents how often their mother, and separately their father, got angry at them, let them know they really cared, let them know they appreciated them, acted loving and affectionate, shouted or yelled at them, insulted or swore at them, and lost their temper and yelled when they did something wrong. The negative items were reverse coded and the items were averaged to create a continuous scale (α = 0.84). Finally, school grades was an item tapping the grades respondents usually got in school (1 = mostly Fs, 9 = mostly As).

Analytic Strategy

There were three phases to the analyses. The first two examined the first hypothesis regarding the link between victimization and decreases in future friend support. First, differences in perceived friend support were descriptively examined across waves 2–5 for victims and non-victims (i.e., youth who were victimized at wave 1 and youth who were not). To do this, t-tests were estimated comparing the means on each friend support item by victim status at wave 1. To illustrate the descriptive findings, the means on three of the friend support items were graphed by wave and victim status.

Second, two random effects regression models were specified to assess the within-person association of victimization with perceived friend support among the full analytical sample. One model included just victimization and the control variables, and the other model added the social network and risky behavior indicators. To illustrate, the substantive part of the equation for the second model was as follows (where ti indicates “this wave” and ranges from 1–5):

The resulting victimization coefficient indicated whether respondents had higher or lower perceived friend support during waves when they experienced more victimization.

The use of random effects models accomplished several things. For example, the data were nested (observations within respondents), and these models allowed the standard errors to be adjusted for clustering by adding a separate error term for the higher-order (here, respondent) level (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Preliminary analyses also indicated that these full-sample models needed an error term for wave of data collection (i.e., the time trend in support significantly differed across respondents), so one was included. Error terms for school district were not needed.

Of more substantive importance is the fact that the panel data and model allowed for the impacts of changes in victimization to be examined. One major concern in correlational studies is selection bias, or the concern that the observed associations reflect not the actual effects of the predictors of interest, but rather un-modeled differences between people with varying scores on those predictors. The models tackle this concern in two ways: through control variables (as in a single-level regression) and through the decomposition of the victimization predictor into a time-varying and a time-stable component. That is, the predictors included not only the respondent’s victimization score at a given wave, but also the respondent’s average victimization score across all waves. The average score acts thus as a control variable for victimization at each wave, leaving the latter coefficient to be determined only by within-individual change. That coefficient is comparable to a fixed-effects coefficient, and because it is based only on wave-to-wave change, it is free from bias due to unobserved time-stable confounds (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; see also Osgood, 2010 for a description of and variations on this method). This excludes a large pool of potential confounds.

The third phase of the analysis examined the remaining hypotheses regarding the factors that explain variability in perceived friend support among victimized youth. This entailed the estimation of another random effects regression model, this time among the subsample of respondents who had been victimized at wave 1. Indicators for subsequent victimization, social network status, and risky behaviors were the predictors of interest.

Results

Victimization and Changes in Perceived Friend Support

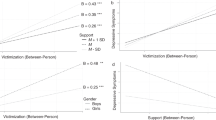

Using the full sample, descriptive analyses examined whether victimization was associated with lower perceived friend support. T-tests revealed that respondents who had been victimized at wave 1 scored significantly lower than those who had not on all of the perceived friend support items at all four follow-up waves (all p < 0.001). Fig. 1 shows illustrative descriptive findings for three indicators of support: whether respondents agreed that their friends cared about them, that their friends stuck up for them, and that they could count on their friends when they needed them. At wave 2, relative to respondents who were not victimized at wave 1, victimized respondents scored approximately half a standard deviation lower than non-victimized respondents on each of these items. Some of these gaps narrowed over the next three years, though none closed completely. Comparable patterns were found for the other support items (not shown). Thus, the key takeaways from Fig. 1 are that wave 1 victims and non-victims differ in their levels of peer support, but these differences may lessen over time.

The next analyses examined the within-person victimization-support association across all waves of the data. Model 1 of Table 2 shows that net of the controls and all time-stable factors, a one-unit increase in victimization (i.e., experiencing one additional type of victimization) was associated with a 0.08 decrease in perceived friend support. This represents a decrease of about 13% of a standard deviation (SDsupport = 0.62). Model 2 shows that this association was not explained by social network status or risky behaviors. Examination of the coefficients revealed that respondents perceived higher friend support during waves when they reported having more friends, though the magnitude of this association decreased as their reported number of friends increased. During waves when respondents had more deviant friends, they perceived lower friend support. As can be seen, however, the victimization coefficient was unchanged when these factors were added to the model.

Predictors of Perceived Friend Support among Victims

To determine the predictors of friend support among victims, the next step was to examine whether social network status, risky behaviors, or subsequent victimization explained variation in perceived friend support among the subset of respondents who were victimized at wave 1. Table 3 shows the results. Two factors were associated with decreases in perceived friend support among victims: increases in victimization (b = −0.07, p < 0.001) and increases in deviant friends (b = −0.10, p = 0.01). In contrast, increases in the self-reported number of friends was associated with increases in perceived friend support, though again a significant squared term indicated that this association weakened as the number of reported friends increased. Friendship nominations received had an independent positive association with perceived friend support (b = 0.02, p = 0.04). The four effect sizes were modest (e.g., experiencing one more type of victimization was associated with a decrease in support of 10% of a standard deviation, and receiving one more friendship nomination was associated with an increase of 3% of a standard deviation), but they were visible net of the control variables and all unobserved time-stable factors.Footnote 2

A comparison of the results from Table 3 with those from model 2 of Table 2 revealed that similar factors also predicted perceived friend support among the victim subsample and the full sample (comprised of victims and non-victims). A supplemental interaction term model (see appendix A) revealed only one significant difference between wave 1 victims and non-victims in the associations of subsequent victimization, friend deviance, number of friends and popularity with perceived friend support at waves 2–5. Specifically, delinquency scores were associated with lower perceived friend support among non-victims; the analogous association among victims was positive and close to 0. These results and their implications are discussed in more detail below.

Discussion

Adolescence can be a challenging period marked by numerous physiological and social changes. During this time, supportive friendships become increasingly important and can foster healthy development into adulthood (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). For youth who are victimized, however, these friendships may be disrupted. Research shows that adolescent victimization negatively affects peer relationships, although the impact of victimization on perceived friend support has been understudied. Questions also remained regarding why some youth, after being victimized, face greater risks for friendship-based consequences. With these issues in mind, in the current study it was examined whether victimization affects perceived friend support, as well as the factors that explain which victimized youth are most likely to experience decreased support. Given the findings presented, three broad conclusions are warranted.

First, it was found that victimization decreased friend support across adolescence. The overall effect was modest in magnitude yet robust given the methodological approach. This finding is notable given that perceived social support, especially from peers, is known to be a significant protective factor in the lives of youth (Mackin et al., 2017). With fewer supportive friendships to draw from, victimized youth may not have sufficient social resources to help them cope and recover in positive ways. Through processes of cumulative and interactional continuity, it is possible that decreased friend support further compounds the harms of victimization and leads to additional disadvantages over the life course (Turanovic, 2018). The results confirm related findings from cross-sectional research (Holt & Espelage, 2007) and suggest that, on average, victimization can be a stigmatizing and alienating experience in adolescence (Graham, 2016).

Nevertheless, the second key conclusion is that the effects of victimization on perceived friend support are heterogeneous—that is, not all victimized youth are likely to suffer this particular social consequence. Variation in perceived friend support among the victim sample could be attributed in part to the following factors: subsequent victimization, self-reported number of friends, friendship nominations received from the larger peer network, and affiliating with deviant friends. With respect to subsequent victimization, the results suggest, as hypothesized, that the more victimization happens, the more support from friends decreases. This is possibly because youth who are victimized more often are viewed as less sympathetic, more blameworthy, or more of a drain on their friends’ support resources (Bukowski & Sippola, 2001). Repeat victims may thus be particularly vulnerable to suffering negative consequences, where it becomes increasingly difficult to rebuild friend support after each subsequent victimization. Even though the effect of victimization on perceived friend support dissipates over time, as suggested in Fig. 1, repeated instances of victimization likely prolong these losses in support. This means that victimized youth who need friend support the most may have the greatest difficulty obtaining it.

Additionally, the results showed that the number of friends victims have, whether measured through self-reports or through a network-based measure, were associated with increased friend support. It may be that youth with more friends are viewed more sympathetically or that they have more people who are willing to take their side in the aftermath of victimization (Dawes & Malamut, 2020). With more perceived friend support, such youth should be better equipped to cope with and recover from victimization. Even so, this beneficial association was found to decrease as the number of friends increased. This is consistent with research suggesting that higher status youth suffer more after being victimized (Faris & Felmlee, 2014). Despite these findings, this study did not examine how short-lived or long lasting changes in perceived friend support were for victims, or whether increased support coincided with any gains in status, likability, or reduced distress. Friend support is just one facet of social acceptance, and there is more to unpack regarding the dynamic associations between victimization, social support, and social standing. Future work could build upon the findings by specifying causal pathways between victimization and perceived friend support via other social network indicators, or by examining the cascading harms of reduced friend support on social status and subsequent victimization across adolescence.

With respect to risky activities, the results showed that victims who affiliated with deviant friends experienced losses in perceived friend support. Research has indicated that deviant youth have lower empathy and social competence (Robinson et al., 2007), which can affect their ability and willingness to provide support to their victimized friends. Deviant friends may also carry attitudes that view victimization as a weakness, or they may even have been the perpetrators of victimization themselves (Schreck et al., 2004). In the broader peer group, it is possible, too, that youth are seen as more to blame for their own victimization if they hang around delinquent others, resulting in less support. Unlike the study hypothesized, affiliating with deviant friends was the only risky behavior linked to changes in friend support among victims. Considering that victims’ own levels of aggression, delinquency, and binge drinking were unrelated to changes in friend support, it could be that victimized youth are judged and evaluated more harshly for who they hang out with than their own behaviors. Attributional research that can directly assesses perceptions of victimized youth who affiliate with deviant peers is needed to clarify these explanations.

Third, from a policy perspective, the findings help to identify risk markers for youth who are most in need of support interventions during adolescence. Whereas most school-based interventions for victimization focus on changing normative beliefs about the acceptability of aggression (Maher et al., 2014), the findings emphasize the need to help victimized youth—especially those with deviant friends and who are of lower social status—develop better friendship skills and social competence (Turanovic et al., 2022).

Further, supplemental interaction analyses revealed that most predictors of friend support (subsequent victimization, number of friends, and affiliating with deviant friends) did not differ between victims and non-victims. Although delinquency was associated with lower perceived friend support among non-victimized youth, no factor uniquely predicted support among victimized youth. Most of the examined factors may therefore operate as more universal sources of friend support that could be recognized in programming and peer-based interventions for all youth (victims and non-victims). Indeed, support programs are likely to be most effective when they target the peer group as a whole (Garandeau et al., 2014). Still, it is unknown how effective friend support was in helping youth positively overcome their experiences with victimization, or how well victimized youth were able to activate support from their friends. To best inform policy, it is crucial to not only recognize the importance of friendship support networks, but also to help youth develop the tools needed to effectively garner support from their networks in times of need (Holt & Espelage, 2007).

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

While the findings add to the extant literature on the consequences of victimization, there are several limitations to recognize and various avenues for future research to build upon. For one, the focus of this study was solely on perceived friend support, but there are other forms of support to examine in relation to victimization. How well victimized youth can access support in other domains of their life—such as at home (e.g., from siblings, parents, or other family members), in the community (e.g., from mentors), or at school (e.g., from teachers, coaches, counselors)—is unknown. Some research shows that support from teachers can be protective for victims even when support from peers is low (Coyle et al., 2022). Still, the results from the current study raise the question: When support from friends dissipates, which victimized youth are able to access to support in other contexts? The answer to this can help to further identify youth most in need of victim assistance and support programs.

Moreover, the extent to which various consequences of victimization vary by gender should be examined, as the analyses indicated that male victims were most likely to suffer losses in support. Broader research suggests that girls perceive more social support than boys, and that girls’ friendships tend to be more intimate (Rose et al., 2016), which may explain these gendered differences. But given the nature of the data, it was not possible to assess directly how peers’ perceptions of victims varied by gender, or how the severity and type of victimization experienced by girls and boys affected their friends’ responses. The data also did not include details on victimization incidents that are relevant for understanding variation in friend support, such as how severe the victimization was perceived to be, if physical injuries were sustained, who the perpetrator was, or where it happened. These details are rarely available in longitudinal youth surveys, yet they should be considered in future research on the consequences of victimization.

Additionally, since this study relied on self-report measures, it is possible that the correlation that was observed between victimization and perceived friend support could be due, at least in part, to shared method variance. Even though there were several correlations between other self-reported indicators and perceived friend support that were near zero—suggesting that shared method variance was not a major concern (Brannick et al., 2010)—it would be beneficial in future work to use alternate measures of youth victimization (e.g., teacher reports, parent reports, official school reports) and friend support (e.g., reports from friends about the types and degree of support they provide) to assess the robustness of the findings.

The predictors that were examined also could interact to predict social support. This possibility follows from work suggesting that the consequences of deviance are different for high- and low-status youth (e.g., Gommans et al., 2017; Malamut et al., 2022). As was noted in the results section, the supplemental analyses revealed some evidence of this, but a full examination of these risky behavior-by-status interactions was beyond the scope of this paper. Future research should continue to explore whether the consequences of victimization differ for youth with different constellations of risk and protective factors for deviant behavior.

It should also be noted that the PROSPER sample is drawn from schools and towns that are relatively small, predominantly White, and in which a notable proportion of lower income families reside. The stigma of victimization and its impacts on friend support may vary in more populous urban settings, in communities and schools where violence is more common, or where cultural norms dictate the use of aggression to solve disputes. Future research aimed at examining how victimization impacts friendships should consider using more racially, ethnically, and economically diverse samples to determine whether the results of the current study extend to other populations.

Lastly, it is important to recognize that the study period spanned early to mid-adolescence, and it is unclear whether the patterns we presented would carry through to the later teen years. In early adolescence, concerns over status enhancement are particularly salient, and peer victimization during this developmental phase is often guided by a desire for social dominance and popularity (Graham, 2016). These sorts of motives may wane with age—especially as youth’s capacity for empathy increases (Allemand et al., 2015)—which can influence the amount of support victims are provided. As work in this area progresses, it would be useful to determine if the effect of victimization on friend support changes later in adolescence, or whether the sources of variability in friend support that we identified are age graded.

Conclusion

A wealth of research suggests that adolescent victimization can be a difficult experience that impacts social relationships. By directly linking within-person changes in victimization to reductions in peer support, this study helps to extend this line of work. Likewise, this study adds to the growing literature demonstrating that victimized youth are a heterogeneous group by determining that the effects of victimization on friend support vary by subsequent victimization, number of friends, and deviant friends. Among victims, it was found that subsequent victimization and affiliating with deviant friends decreased friend support, whereas having more friends increased friend support. However, the positive association between number of friends and peer support was weakened among more popular victims. Together, these findings confirm that peer contexts meaningfully shape the consequences of youth victimization. Moving forward, the conditions under which losses in friend support lead to additional disadvantages over the life course should be identified.

Notes

The multiple imputation routine included 63 items in total. These were the individual items that comprised all of the study’s variables in addition to 12 auxiliary variables, namely an indicator of marijuana use and 11 items assessing various internalizing symptoms. All scale variables were created following the imputation. Marijuana use was unrelated to friend support in the bivariate analysis and was not included in the final analyses. Internalizing symptoms were not included in the paper because they did not follow from our conceptual framework, which focused on risky behaviors and network status. However, these measures did inform the imputation of item-missing data.

Interactions were also examined between the risky behavior variables and the network status variables among the victim subsample. Only one association was statistically significant. This association (a three-way interaction between friend deviance, self-reported number of friends, and number of friends squared) suggested that the impact of friend deviance on perceived support was most strongly negative among respondents with few self-reported friends, but that as the self-reported number of friends increased, number of friends had an increasingly weak buffering effect on the influence of friend deviance. This interaction was not replicated when the friendship nominations received variable was used in the interaction term, nor was it replicated for any other of the three measures of respondents’ risky behaviors.

References

Allemand, M., Steiger, A. E., & Fend, H. A. (2015). Empathy development in adolescence predicts social competencies in adulthood. Journal of Personality, 83(2), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12098.

Archer, J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology, 8(4), 291–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291.

Borelli, J. L., & Prinstein, M. J. (2006). Reciprocal, longitudinal associations among adolescents’ negative feedback-seeking, depressive symptoms, and peer relations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34(2), 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-005-9010-y.

Boulton, M. J. (2013). The effects of victim of bullying reputation on adolescents’ choice of friends: Mediation by fear of becoming a victim of bullying, moderation by victim status, and implications for befriending interventions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 114(1), 146–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2012.05.001.

Brannick, M. T., Chan, D., Conway, J. M., Lance, C. E., & Spector, P. E. (2010). What is method variance and how can we cope with it? A panel discussion. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109360993.

Bukowski, W., & Sippola, L. (2001). Groups, individuals, and victimization: A view of the peer system. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 355–377). Guilford Press.

Cooley, J. L., Fite, P. J., Rubens, S. L., & Tunno, A. M. (2015). Peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and rule-breaking behavior in adolescence: The moderating role of peer social support. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 37(3), 512–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-014-9473-7.

Coyle, S., Weinreb, K. S., Davila, G., & Cuellar, M. (2022). Relationships matter: The protective role of teacher and peer support in understanding school climate for victimized youth. Child & Youth Care Forum, 51, 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09620-6.

Cui, M., Conger, R. D., Bryant, C. M., & Elder, Jr, G. H. (2002). Parental behavior and the quality of adolescent friendships: A social‐contextual perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(3), 676–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00676.x.

Dawes, M., & Malamut, S. (2020). No one is safe: Victimization experiences of high-status youth. Adolescent Research Review, 5, 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-018-0103-6.

Dijkstra, J. K., Cillessen, A. H. N., & Borch, C. (2013). Popularity and adolescent friendship networks: Selection and influence dynamics. Developmental Psychology, 49(7), 1242–1252. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030098.

Dumas, T. M., Davis, J. P., & Ellis, W. (2019). Is it good to be bad? A longitudinal analysis of adolescent popularity motivations as a predictor of engagement in relational aggression and risk behaviors. Youth & Society, 51(5), 659–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X17700319.

Esbensen, F. A., & Carson, D. C. (2009). Consequences of being bullied: Results from a longitudinal assessment of bullying victimization in a multisite sample of American students. Youth & Society, 41(2), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X09351067.

Estell, D. B., & Perdue, N. H. (2013). Social support and behavioral and affective school engagement: The effects of peers, parents, and teachers. Psychology in the Schools, 50(4), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21681.

Evans, S. C., Fite, P. J., Hendrickson, M. L., Rubens, S. L., & Mages, A. K. (2015). The role of reactive aggression in the link between hyperactive–impulsive behaviors and peer rejection in adolescents. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 46(6), 903–912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0530-y.

Faris, R., & Felmlee, D. (2014). Casualties of social combat: School networks of peer victimization and their consequences. American Sociological Review, 79(2), 228–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414524573.

Forsberg, C., & Thornberg, R. (2016). The social ordering of belonging: Children’s perspectives on bullying. International Journal of Educational Research, 78, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2016.05.008.

Fosco, G. M., & Feinberg, M. E. (2015). Cascading effects of interparental conflict in adolescence: Linking threat appraisals, self-efficacy, and adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 27(1), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000704.

Garandeau, C. F., Lee, I. A., & Salmivalli, C. (2014). Differential effects of the KiVa anti-bullying program on popular and unpopular bullies. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2013.10.004.

Gollwitzer, M., Süssenbach, P., & Hannuschke, M. (2015). Victimization experiences and the stabilization of victim sensitivity. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 439 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00439.

Gommans, R., Müller, C. M., Stevens, G. W., Cillessen, A. H., & Ter Bogt, T. F. (2017). Individual popularity, peer group popularity composition and adolescents’ alcohol consumption. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(8), 1716–1726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0611-2.

Graham, S. (2016). Victims of bullying in schools. Theory Into Practice, 55(2), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1148988.

Graham, S., & Juvonen, J. (2001). An attributional approach to peer victimization. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 49–72). Guilford Press.

Holt, M. K., & Espelage, D. L. (2007). Perceived social support among bullies, victims, and bully-victims. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(8), 984–994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9153-3.

Hutzell, K. L., & Payne, A. A. (2012). The impact of bullying victimization on school avoidance. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 10(4), 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204012438926.

Kreager, D. A., Rulison, K., & Moody, J. (2011). Delinquency and the structure of adolescent peer groups. Criminology, 49(1), 95–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00219.x.

La Greca, A. M., Ehrenreich-May, J., Mufson, L., & Chan, S. (2016). Preventing adolescent social anxiety and depression and reducing peer victimization: Intervention development and open trial. Child & Youth Care Forum, 45, 905–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9363-0.

Lippold, M. A., Greenberg, M. T., & Feinberg, M. E. (2011). A dyadic approach to understanding the relationship of maternal knowledge of youths’ activities to youths’ problem behavior among rural adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(9), 1178–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9595-5.

Mackin, D. M., Perlman, G., Davila, J., Kotov, R., & Klein, D. N. (2017). Social support buffers the effect of interpersonal life stress on suicidal ideation and self-injury during adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 1149–1161. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003275.

Maher, C. A., Zins, J., & Elias, M. (2014). Bullying, victimization, and peer harassment: A handbook of prevention and intervention. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315808666.

Malamut, S. T., Dawes, M., Lansu, T. A., van den Berg, Y., & Cillessen, A. H. (2022). Differences in aggression and alcohol use among youth with varying levels of victimization and popularity status. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01649-7.

Malamut, S. T., Dawes, M., van den Berg, Y., Lansu, T. A., Schwartz, D., & Cillessen, A. H. (2021). Adolescent victim types across the popularity status hierarchy: Differences in internalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(12), 2444–2455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01498-w.

Malamut, S. T., van den Berg, Y. H. M., Lansu, T. A. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2020). Bidirectional associations between popularity, popularity goal, and aggression, alcohol use and prosocial behaviors in adolescence: A 3-year prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 298–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01308-9.

Osgood, D. W. (2010). Statistical models of life events and criminal behavior. In A. R. Piquero & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Handbook of Quantitative Criminology (pp. 375–396). Springer.

Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29(4), 611–621. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.611.

Pratt, T. C., Turanovic, J. J., Fox, K. A., & Wright, K. A. (2014). Self‐control and victimization: A meta‐analysis. Criminology, 52(1), 87–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12030.

Randa, R., Reyns, B. W., & Nobles, M. R. (2019). Measuring the effects of limited and persistent school bullying victimization: Repeat victimization, fear, and adaptive behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(2), 392–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516641279.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models (second edition). Sage.

Robinson, R., Roberts, W. L., Strayer, J., & Koopman, R. (2007). Empathy and emotional responsiveness in delinquent and non‐delinquent adolescents. Social Development, 16(3), 555–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00396.x.

Rose, A. J., Smith, R. L., Glick, G. C., & Schwartz-Mette, R. A. (2016). Girls’ and boys’ problem talk: Implications for emotional closeness in friendships. Developmental Psychology, 52(4), 629–639. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000096.

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley.

Schreck, C. J., Fisher, B. S., & Miller, J. M. (2004). The social context of violent victimization: A study of the delinquent peer effect. Justice Quarterly, 21(1), 23–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820400095731.

Sentse, M., Dijkstra, J. K., Salmivalli, C., & Cillessen, A. H. (2013). The dynamics of friendships and victimization in adolescence: A longitudinal social network perspective. Aggressive Behavior, 39(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21469.

Shaheen, A. M., Hamdan, K. M., Albqoor, M., Othman, A. K., Amre, H. M., & Hazeem, M. N. A. (2019). Perceived social support from family and friends and bullying victimization among adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 107, 104503 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104503.

Smångs, M. (2010). Delinquency, social skills and the structure of peer relations: Assessing criminological theories by social network theory. Social Forces, 89(2), 609–631. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0069.

Solberg, M. E., & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29(3), 239–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10047.

Spoth, R., Greenberg, M., Bierman, K., & Redmond, C. (2004). PROSPER community–university partnership model for public education systems: Capacity-building for evidence-based, competence-building prevention. Prevention Science, 5(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:prev.0000013979.52796.8b.

Spoth, R., Trudeau, L., Redmond, C., Shin, C., Greenberg, M. T., Feinberg, M., & Hyun, G. (2015). PROSPER partnership delivery system: Effects on adolescent conduct problem behavior outcomes through 6.5 years past baseline. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.008.

Stanton-Salazar, R. D., & Spina, S. U. (2005). Adolescent peer networks as a context for social and emotional support. Youth & Society, 36(4), 379–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X04267814.

Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 2, 55–87. https://doi.org/10.1891/194589501787383444.

Sweeten, G. (2012). Scaling criminal offending. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 28(3), 533–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9160-8.

Swirsky, J. M., & Xie, H. (2021). Peer-related factors as moderators between overt and social victimization and adjustment outcomes in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(2), 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01313-y.

Tomlinson, T. A., Mears, D. P., Turanovic, J. J., & Stewart, E. A. (2021). Forcible rape and adolescent friendship networks. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9-10), 4111–4136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518787807.

Turanovic, J. J. (2018). Toward a life course theory of victimization. In S. H. Decker & K. A. Wright (Eds.), Criminology and public policy: Putting theory to work (pp. 85–103). Temple University Press.

Turanovic, J. J. (2019). Heterogeneous effects of adolescent violent victimization on problematic outcomes in early adulthood. Criminology, 57(1), 105–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12198.

Turanovic, J. J., Pratt, T. C., Kulig, T. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2022). Confronting school violence: A synthesis of six decades of research. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108891998.

Turanovic, J. J., & Young, J. T. N. (2016). Violent offending and victimization in adolescence: Social network mechanisms and homophily. Criminology, 54, 487–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12112.

Velicer, W. F., Govia, J. M., Cherico, N. P. & Corriveau, D. P. (1985). Item format and the structure of the Buss‐Durkee hostility inventory. Aggressive Behavior, 11(1), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1985)11:1<65::AID-AB2480110108>3.0.CO;2-H.

Wallace, L. N., & Ménard, K. S. (2017). Friendships lost: The social consequences of violent victimization. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 26(2), 116–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2016.1250852.

Wang, W., Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H. L., McDougall, P., Krygsman, A., Smith, D., Cunningham, C. E., Haltigan, J. D., & Hymel, S. (2014). School climate, peer victimization, and academic achievement: Results from a multi-informant study. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(3), 360–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000084.

Yeung, R. S., & Leadbeater, B. J. (2007). Does hostile attributional bias for relational provocations mediate the short-term association between relational victimization and aggression in preadolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(8), 973–983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9162-2.

Acknowledgements

Grants from the W.T. Grant Foundation (8316), National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA018225), and National Institute of Child Health and Development (R24-HD041025) supported this research. The analyses used data from PROSPER, a project directed by R. L. Spoth, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA013709) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA14702). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authors' Contributions

J.T. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted the manuscript; S.S. participated in the design and coordination of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript; K.L. assisted with the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Sharing Declaration

This manuscript’s data will not be deposited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

No data identifiable to a person were collected by the researchers.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Table 4

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Turanovic, J.J., Siennick, S.E. & Lloyd, K.M. Consequences of Victimization on Perceived Friend Support during Adolescence. J Youth Adolescence 52, 519–532 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01706-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01706-1