Abstract

As friends increase in closeness and influence during adolescence, some friends may become overprotective, or excessively and intrusively protective. Engaging in overprotective behavior, and being the recipient of such behavior, may have positive and negative adjustment trade-offs. The current study examines, for the first time, bidirectional associations between friend overprotection and several adjustment trade-offs, including internalizing problems (i.e., depressive and anxiety symptoms), peer difficulties (i.e., rejection and physical and relational victimization), and positive friendship quality (i.e., closeness, help, and security) during early adolescence. Participants were 269 young adolescents (140 boys; Mage = 11.46, SD = 0.41) who completed self-report and peer nomination measures in their schools at two time points 4 months apart (Fall and Spring of the school year). Structural equation models revealed that being overprotected by a friend predicted decreases in friendship quality and was predicted by peer difficulties and internalizing problems (negatively). Being overprotective of friends predicted increases in internalizing symptoms and was predicted by peer difficulties. Findings are novel as they suggest that friend overprotection may be risky (and not beneficial) for both the overprotector and the overprotectee, setting the stage for future inquiry in this new area of peer relations research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Understanding the nature and impact of friendship experiences during early adolescence (10–14 years) is important, as early adolescence is when friendships increasingly influence, for better or worse, a myriad of adjustment outcomes (Bagwell & Bukowski, 2018). While research has traditionally investigated friendship in terms of quantity and overall quality (Hartup, 1995), more recent research has underscored the significance of specific friendship features and processes that may simultaneously have adaptive and maladaptive adjustment “trade-offs” (Bagwell et al., 2021; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Yet, the range of identified friendship features with such trade-offs is still limited in scope. The present study aimed to shed light on the potential psychosocial adjustment trade-offs of an understudied feature of friendships: overprotection. Overprotection is broadly defined as a constellation of behaviors that aim to minimize or protect from harm, when such protection is not warranted, through restriction of autonomous behavior (Thomasgard & Metz, 1993). Of particular interest to this study were the relations between friend overprotection (both being the overprotector and being the recipient of overprotection) and several psychosocial adjustment indicators, including internalizing problems (i.e., depressive and anxiety symptoms), peer difficulties (i.e., rejection and physical and relational victimization), and positive friendship quality (i.e., closeness, help, and security). These associations are presumed to be bidirectional in nature, but this has yet to be empirically tested.

Theory and Research on Friend Overprotection

Within the larger friendship literature, protection is oftentimes studied and conceptualized as a positive friendship feature, with research showing that it is related to positive indices of adolescent functioning and well-being, such as reduced victimization and internalizing symptoms (e.g., Hodges et al., 1999; Woods et al., 2009). Overprotection, however, involves protective behavior that is neither warranted nor appropriate (i.e., given the friend’s capabilities, the situation, and/or developmental level), and therefore may carry different effects. As an illustrative example, protection might involve helping a friend stand up to a bully, whereas overprotection might involve speaking to a would-be bully to prevent potential conflict, particularly when such an intervention is unsolicited by the friend. In this example, both protection and overprotection are aimed at shielding one’s friend from problems, but only overprotection is intrusive, excessive, and unnecessary. It is also autonomy-limiting insofar as such behavior prevents the friend from making independent decisions about if, when, or how to handle the situation with the potential bully. In this vein, friend overprotection may best be conceptualized as a “maladaptive variant” of protection (Berndt & McCandless, 2009; Etkin & Bowker, 2018). Because it stems from the (positive) intent to protect, this variant could foster feelings of closeness, security, and help within the friendship. Drawing from Sullivan’s (1953) Interpersonal Theory, however, this variant could also interfere with the equality and reciprocity that is essential to young adolescent friendships and their positive provisions, thereby leading to increased feelings of distress. An adolescent on the receiving end of a friendship like this may also invite peer difficulties by fostering perceptions of atypicality and weakness/vulnerability.

Preliminary support for these ideas is found in two studies that examined associations between friend overprotection and assumed positive and negative psychosocial outcomes. In the first, two-part study (Ns = 179–270; ages 10–16), authors used high scores on a measure of friend protection to assess friend overprotection, and found that it was positively, prospectively, and uniquely (i.e., controlling for other friendship qualities) related to depressive symptoms, and concurrently to peer victimization (Etkin & Bowker, 2018). Authors also modified a parental overprotection measure to be specific to friend overprotection and found that it was positively, concurrently, and uniquely (i.e., controlling for maternal overprotection) associated with friendship support, anxiety, emotion dysregulation, and social difficulties (Etkin & Bowker, 2018).

In the second study, authors examined concurrent associations between psychosocial adjustment and friend overprotection, using a new measure they developed, in a sample of emerging adults (N = 363; ages 18–25; Etkin et al., 2022). Results again showed that friend overprotection was positively, concurrently, and uniquely (i.e., controlling for helicopter parenting, which is similar to overprotection) associated with positive friendship quality (e.g., closeness), social anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Further, these associations were explained by reduced feelings of friend autonomy support, suggesting that overprotective behaviors may provide positive provisions within the friendship, but may also lead to feelings of depression and anxiety by interfering with the extent to which youth feel their friend supports their autonomy. Such notions are consistent with Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2000), which posits that individuals are driven to feel connected to others, but also need to feel competent and autonomous. This theory further posits that the support (or lack thereof) from close others in the attainment of connection, competence, and autonomy, can positively or negatively impact psychological well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2014). The consideration of friend overprotection has been limited to the two aforementioned studies, but findings from research on friend autonomy support supports these SDT ideas as they apply to friendships during adolescence (e.g., Chango et al., 2015; Deci et al., 2006; Demir & Davidson, 2013).

A Bidirectional Model of Friend Overprotection

While the research on friend overprotection provides some evidence of its positive and negative psychosocial outcomes, no study to date has examined bidirectional associations between friend overprotection and these indicators of adjustment. Bidirectional (or transactional) models are a hallmark of developmental psychopathology research, as they help to explain processes underlying adaptation and maladaptation across development (Sameroff & Mackenzie, 2003; Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). Without bidirectional models of friend overprotection there has been limited understanding of why overprotection occurs, and therefore limited ability to draw developmental and clinical implications.

As described above, adolescents who are overprotected may experience more internalizing and peer problems over time. Yet, it also is possible that adolescents struggling with internalizing problems or peer difficulties elicit overprotection from their close friends due to perceptions of vulnerability and need. It may also be that positive friendship quality, especially the features of help, security, and closeness, sets the stage for increased overprotection over time in a similar fashion that close friends engage in increased co-rumination, another friendship feature with positive and negative trade-offs (Rose, 2021). Being overprotected may in turn contribute to increased perceptions of help, security, and closeness, as research indicates that adolescents tend to attribute positive intent to their best friends’ behavior (Bowker et al., 2007). Indeed, in describing a friend’s overprotective behavior, one participant from a prior study remarked “I feel annoyed but I know she’s just looking out for me” (p. 114, Etkin et al., 2022).

Additional support for this potential bidirectional model of overprotection may be found in studies of parent overprotection. For instance, Rapee (2009) found that adolescents’ perceptions of maternal overprotection predicted increases in their own anxiety symptoms one year later, which subsequently predicted increases in maternal overprotection one year later. Parent-child relationships and friendships have clear differences in terms of their structure and dynamics (e.g., friendships tend to be more equalitarian and reciprocal, Sullivan, 1953); yet adolescents may be overprotected by their friends for similar reasons they are by parents (e.g., they appear anxious), and with similar effects.

Research on Being Overprotective

In the limited past research on friend overprotection, there has been an exclusive focus on being the recipient of overprotection, or the overprotectee. As such, there is a gap in the literature regarding engaging in overprotection, or being the overprotector. Specifically, it is unknown whether there are developmental implications for those adolescents who engage in overprotective behaviors in their friendships. It is also not known why some youth may be more likely to engage in such behaviors relative to others, knowledge which would help to develop a more thorough understanding of the understudied friendship feature of overprotection.

While no research exists on being overprotective of one’s friends, there is some evidence from research on related constructs suggesting that like receiving overprotection, it may too be bidirectionally related to positive and negative psychosocial adjustment indicators. For example, research on empathy, caring, and caretaking in adolescence suggests that taking on the tangible or emotional burdens of others (friends, family members) can incur psychological costs such as increased depression and anxiety (Tone & Tully, 2014). Yet, being involved in a friend’s challenges can also have positive trade-offs, namely feeling closer to that friend (Smith & Rose, 2011). Positive friendship quality may also lead to increased overprotective behaviors because youth are motivated to protect these friendships. It is also plausible that youth who are more anxious or depressed may be more likely to engage in overprotective behaviors, perhaps due to their own insecurities and anxieties. Support for this latter idea can also be found in the literature on parent overprotection, which shows that maternal anxiety is prospectively linked with overprotective parenting (Jones et al., 2021). Peer problems may also contribute to engaging in overprotection because if adolescents struggle with their larger peer group, they may be more protective of their close friendships. At the same time, being overprotective could lead to more problems with the larger peer group if this behavior is viewed undesirably or as unacceptable.

Gender Considerations

The extant friendship literature shows numerous gender differences in adolescent friendships (Rose & Asher, 2017). For instance, girls’ friendships tend to emphasize intimate disclosure whereas boys’ friendships tend to emphasize competition and companionship (Rose & Asher, 2017). It is argued that girls are socialized at a young age to value and develop close relationships while boys are socialized towards larger peer-group activities (Maccoby, 1990), which may be why girls tend to be more impacted by stressful friendship experiences than boys (e.g., friendship dissolution; Bowker & Weingarten, 2022). With regard to overprotection, it could be that girls are more likely to protect and overprotect their friends, but due to the non-normative nature of such behaviors, boys suffer more when they are the overprotector and the overprotectee. Consistent with these notions, friend overprotection was related to emotional dysregulation for boys, but not girls, in one study (Etkin & Bowker, 2018). However, this was the only gender-related finding from the study and the only study to examine such differences, highlighting the need for additional research that evaluates whether the interpersonal and socialization experiences of young adolescent boys and girls might lead to gendered pathways involving friend overprotection and psychosocial adjustment. Gender differences were therefore considered in this study.

Current Study

Not only is there a dearth of past research on friend overprotection, but there is only one published longitudinal study which did not examine bidirectional associations with psychosocial adjustment. Moreover, no research has focused on the experience of engaging in overprotection of one’s friends, only being the recipient of it. To address these gaps in the literature, the current study had two aims. The first aim was to examine prospective (i.e., over 4 months) and bidirectional associations between friend overprotection in terms of being overprotected by a friend (i.e., being the overprotectee), and adolescent internalizing problems (i.e., depressive and anxiety symptoms), peer difficulties (i.e., rejection and physical and relational victimization), and positive friendship quality (i.e., closeness, security, and help). Hypotheses were that internalizing problems, peer difficulties, and positive friendship qualities would predict and be predicted by being overprotected. The second aim was to examine prospective and bidirectional associations between friend overprotection in terms of being overprotective of friends (i.e., being the overprotector), and the psychosocial variables described above. Corresponding hypotheses were likewise that internalizing problems, peer difficulties, and positive friendship quality would predict and be predicted by being overprotective. In addition, adolescent gender differences were examined. Hypotheses were that girls would engage in more overprotection, but the negative effects of friend overprotection would be stronger for boys. Similar to past research, all analyses included maternal overprotection as a covariate to evaluate the unique associations between friend overprotection and psychosocial adjustment.

Method

Participants

Participants were 269 6 – 8th grade students (Mage = 11.46, SD = 0.41 at Time 1) from three middle schools in Western New York that participated in a short-term longitudinal study on early adolescent friendships. Participants reported their gender, race, and ethnicity. Fifty-two percent of the sample identified as boys (n = 140). Approximately 60% identified as White, 14% as Arabic, 6% as Black, 5% as Hispanic, and the remaining participants identified as another race or ethnicity, or as multiracial. Publicly available demographic data indicated that median household income for the districts in which the schools were located ranged from $40,669 to $56,531.

Procedure

Schools were first recruited, via emails sent to principals, to participate in a study of early adolescent friendships. Three schools agreed to participate. In these schools, the teachers distributed letters explaining the project and parent consent and adolescent assent forms. Small incentives for returning consent/assent forms were provided, regardless of the decision to participate (consent rate = 71%). Data collections occurred twice, in November/December (T1) and March/April (T2). Participants completed measures in group format in their schools (i.e., in the cafeteria or in homerooms) during non-academic school periods. Doctoral students and trained undergraduate research assistants conducted the data collections. The measures included those described below and several others not of interest to the present study (e.g., assessing prosocial behavior, social withdrawal, friendship conflict). At the end of the packet of measures at both time points, participants could check a box indicating if they wished to speak to a school counselor. All study procedures were approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Measures

Self-Report Measures

Friend Overprotection

A revised version of the Friend Overprotection Scale (FOS; Etkin et al., 2022) was used to assesses perceptions of friend overprotection. For the FOS, 80 items were developed and pilot-tested in a sample of 363 undergraduate students; exploratory factor analysis (EFA) showed support for a 12-item scale with evidence of concurrent and discriminant validity, and good reliability (α = 0.89; see Etkin et al., 2022 for complete details). For the present study, the FOS was revised (and thus became the FOS-R) based on feedback about the FOS provided by several young adolescent volunteers and several experts in the adolescent peer relations field. Given the feedback, the items were revised to achieve three goals: (1) to make the wording more developmentally appropriate, (2) to change references to situations deemed not applicable to young adolescents, and (3) to add more references to the intent to protect/keep from harm. These changes resulted in 15 revised items, which were embedded within the friendship quality measure (described next) and rated on a scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Really true). These items were subjected to an EFA (see below) and the final 12 items are presented in Table 1. Following the EFA, mean scores were calculated at each time point with higher scores indicating greater friend overprotection. The internal consistency was found to be good (T1: α = 0.86; T2: α = 0.87).

Positive Friendship Quality

The Friendship Qualities Scale (FQS; Bukowski et al., 1994) was used to assess several positive features of adolescents’ best friendships. Of particular interest, and included in the present study, were items describing closeness (e.g., “I am happy when I am with my friend”; 5-items; T1: α = 0.82; T2: α = 0.81), security (e.g., “If there is something bothering me, I can tell my friend about it even if it is something I cannot tell to other people”; 2-items; T1: α = 0.74; T2: α = 0.73), and help (e.g., “If I forgot my lunch or needed a little money, my friend would loan it to me”; 5-items; T1: α = 0.70; T2: α = 0.79). These scales were included in a positive friendship quality latent variable. Adolescents rated how true each statement was of their relationship with their best friend on a scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Really true). Mean scores were calculated for each scale with higher scores reflecting greater levels of each positive friendship quality.

Anxiety Symptoms

The social and generalized anxiety subscales of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1999) were used to assess symptoms of anxiety, as part of an internalizing problems latent variable. Adolescents rated items (e.g., “I worry about what is going to happen in the future”; “I don’t like to be with people I don’t know well”) on a scale ranging from 0 (Not true or hardly ever true) to 2 (Very true or often true). Of note, two items from the social anxiety scale were omitted due to conceptual overlap with the construct of shyness, in line with past research (Prinstein et al., 2005). Mean scores were calculated for each scale, with higher scores indicating greater generalized (9-items; T1: α = 0.78; T2: α = 0.82) and social (5-items; T1: α = 0.76; T2: α = 0.78) anxiety.

Depressive Symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A; Johnson et al., 2002) was used to evaluate symptoms of depression, as part of an internalizing problems latent variable. Adolescents rated the frequency of symptoms (e.g., “feeling down, depressed, irritable, or hopeless”) over the past two weeks on a scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Nearly every day). As in past studies, one item assessing suicidal ideation was excluded due to the inability of the research team to monitor individual survey items and IRB request (e.g., Etkin & Bowker, 2018). Higher mean scores indicated greater depressive symptoms (8-items; T1: α = 0.78; T2: α = 0.81).

Maternal Overprotection

Adolescents also completed the Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran – Child Report (EMBU-C; Muris et al., 2003) to assess maternal overprotection. Adolescents rated the items (e.g., “Your mother wants to keep you from all possible dangers”) on a scale of 1 (No, never) to 4 (Yes, most of the time), with higher mean scores indicating greater perceptions of maternal overprotection over the past 3 months (10-items; T1: α = 0.87; T2: α = 0.89). Participants were instructed to complete the measure about a primary caregiver other than a mother, if applicable.

Peer Nominations

Adolescents completed several unlimited peer nomination items for peers in their grade and school. No rosters were provided; nominations were based on free recall and only nominations for participating peers were subsequently considered (e.g., Markovic & Bowker, 2017). Nominations received for each item were summed, then proportionalized by the total number of participants (within each grade and school), and then standardized (again separately within each grade and school; Cillessen, 2009). Higher scores for all constructs described next reflect a greater number of nominations received. A significant strength of peer nominations is that multiple informants report on the behavior and group-level experiences of one individual, which increases the reliability of variables assessed with even single nomination items.

Being Overprotective

A new item was developed for the present study to assess being overprotective of one’s friends: “A person who is overprotective of his or her friends.”

Peer Difficulties

Two items each assessed physical (“Someone who gets hit or kicked by other kids”; “Someone who gets shoved or pushed around by other kids”) and relational (“Someone who other kids say mean things or gossip about”; “Someone who gets left out of activities, excluded, or ignored”) victimization (e.g., Bowker & Raja, 2011). The physical (T1: α = 0.76; T2: α = 0.86) and relational (T1: α = 0.63; T2: α = 0.64) victimization items were averaged at each time point. Consistent with prior research, peer rejection was measured by the single item: “Someone you like to be with least” (Coie et al., 1982). These 3 items were included in a peer difficulties latent variable.

Data Analytic Plan

Preliminary Analyses

Data were first examined for skew, kurtosis, and outliers. Missing data were examined, including conducting Little’s MCAR test to evaluate whether data were missing at random, and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) analyses to evaluate differences on study variables between participants who completed one versus both time points. Next, an EFA of the FOS-R was conducted to examine its factor structure, given the revised items and first-time use in a young adolescent sample. Bivariate correlations and descriptive data were then examined for all measures. Finally, MANOVA analyses also explored for differences in the study variables based on school (coded as 1 = School A, 2 = School B, 3 = School C), race/ethnicity (coded as 1 = White, 2 = Black, 3 = Arabic, 4 = Hispanic, 5 = other or multiracial), and gender (coded as 0 = boys, 1 = girls).

Primary Analyses

A series of measurement models were first evaluated in Mplus Version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) to create latent factors for the internalizing problems, peer difficulties, and positive friendship quality constructs, and to evaluate longitudinal measurement invariance. Structural equation modeling was used to test the primary study hypotheses. Two cross-lagged panel models were specified with peer difficulties, internalizing problems, positive friendship quality, and friend overprotection (one model with the being overprotected by variable and the other with the being overprotective of variable) at T1 and T2 (Selig & Little, 2012). Multigroup models were used to evaluate potential gender differences. In addition to maternal overprotection, findings regarding ethnicity- and school-based differences informed whether these would be included as additional covariates. All paths were freely estimated and allowed to correlate within time points. The Sattora-Bentler scaled chi-square was utilized to test overall model fit (ps > 0.05 considered acceptable), and to evaluate multigroup models (Kline, 2011). Other fit indices used to evaluate the models were the RMSEA (values < 0.06 considered acceptable), SRMR (values ≤ 0.08 considered acceptable), and the CFI and TLI (values ≥ 0.95 considered acceptable). When specified models did not meet criteria for adequate fit, modification indices were consulted to improve model fit.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Skew, Kurtosis, and Missing Data

In examining skew and kurtosis, all data were found to be normally distributed except for the peer nomination data (skew > 3); this is typical of this type of data and was accommodated using the Maximum Likelihood Robust (MLR) estimator in Mplus analyses. Regarding missing data, more than 10% of observations were missing at each time point (15% at T1 and 12% at T2), which was also accommodated by the MLR estimator. Little’s MCAR test revealed that data were missing completely at random (p = 0.08). Twenty-five students who participated at T1 were not present at T2 due to being absent on the day of data collection or switching schools. In addition, 29 students participated at T2 who were not present at T1 due to absence. Six students were not present at either time point but were included in the final analyses because they received peer nomination data. MANOVA analyses revealed one significant difference on key study variables between students with complete and incomplete data; participants with only one time point of data had higher average friend overprotection scores (M = 3.27, SE = 0.18) than those with two time points of data (M = 2.87, SE = 0.06), F(1) = 4.75, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.02.

Exploratory Factor Analysis of the FOS-R

Initial parallel analyses and an examination of scree plots and eigenvalues (>1.0) revealed that no more than one factor should be extracted from the data at each time point. Solutions with more than one factor also revealed non-meaningful loading patterns, both statistically and conceptually. As such, a 1-factor EFA was tested. At T1, three items were dropped with factor loadings below 0.40 and redundant content. These same items were dropped at T2, and the 1-factor EFAs revealed factor loadings ranging from 0.44 to 0.75, resulting in 12-items included in the final scale. Items and factor loadings are presented in Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations for, and bivariate correlations among all study variables are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Of note, friend overprotection assessed with the FOS-R (being overprotected) was correlated positively with each of the FQS scales at both time points. It was also correlated negatively with peer rejection at T1. At T2, the FOS-R was correlated positively with depressive symptoms. Peer-nominated friend overprotection (i.e., being overprotective) was correlated positively with peer rejection and relational victimization at T2. MANOVA analyses revealed several differences on the study variables based on school and adolescent gender (but not race/ethnicity). For gender differences, girls scored higher than boys on closeness, help, security (T1 only), being overprotected (FOS-R), and being overprotective (peer-nomination, T1 only; all ps < 0.01). Boys scored higher in terms of peer rejection and relational and physical victimization (ps < 0.01). There were also school differences in closeness, help, security, and being overprotected (ps < 0.01). As such, school was included as an additional covariate in primary analyses.

Primary Analyses

Measurement Models

The FOS-R scale (χ2 (250) = 426.61, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI/TLI = 0.90/0.89, SRMR = 0.06), friendship quality latent variable (χ2 (7) = 9.83, p = 0.20, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI/TLI = 1.00/0.99, SRMR = 0.03), and peer difficulties latent variable (χ2 (7) = 8.91, p = 0.26, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI/TLI = 1.00/1.00, SRMR = 0.03) were fully metric invariant over time. The latent variables representing internalizing problems (generalized and social anxiety, and depressive symptoms) were partially metric variant over time, as modification indices suggested depressive symptoms should be free to vary (χ2 (6) = 1.51, p = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.00, CFI/TLI = 1.00/1.03, SRMR = 0.01). Given that at least partial metric invariance was established for all factors, factor-output scores were computed to use as manifest variables in the structural equation models (Muthén & Muthén, 1998 –2017).

Structural Models

Being Overprotected

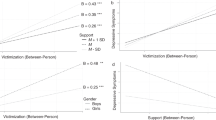

The model testing bidirectional associations between the FOS-R (i.e., being overprotected) and internalizing problems, peer difficulties, and positive friendship quality variables fit the data very well, χ2 (13) =17.11, p = 0.19, RMSEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.02, CFI/TLI = 1.00/0.99. The Satorra-Bentler chi-square difference test revealed that the free model was not a significantly better fit to the data than a model in which gender was constrained across parameters, χ2 (43) = 36.46, p = 0.75. Gender was therefore instead included as a covariate, along with school and maternal overprotection. Path coefficients are presented in Fig. 1. T1 peer difficulties positively, and T1 internalizing problems negatively, predicted T2 friend overprotection (ps < 0.05). Friend overprotection at T1 also negatively predicted positive friendship quality at T2 (p < 0.05). The reverse directions of effects were not significant. Examining within-time associations, friend overprotection was associated uniquely and positively with positive friendship quality but was not significantly associated with peer difficulties or internalizing problems. Regarding covariates (not pictured in Fig. 1), gender predicted friend overprotection (T1: B = 0.44, p < 0.001; T2: B = 0.13, p < 0.05), positive friendship quality (T1: B = 0.43, p < 0.001; T2: B = 0.11, p < 0.05), internalizing problems (T1: B = 0.08, p < 0.05), and peer difficulties (T1: B = −0.33, p < 0.001). School was associated with positive friendship quality (T1: B = −0.15, p < 0.001; T2: B = −0.06, p < 0.01). Maternal overprotection was associated with the FOS-R within time points (Bs = 0.15 – 0.28, ps < 0.05) and prospectively (B = 0.13, p < 0.05). It was also associated with peer difficulties at T1 (B = 0.14, p < 0.05) and internalizing problems at T2 (B = 0.18, p < 0.01).

Being Overprotective

The model testing bidirectional associations between peer-nominated overprotection variable (i.e., being overprotective) and the internalizing problems, peer difficulties, and positive friendship quality variables fit the data well, χ2 (13) = 16.84, p = 0.21, RMSEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.02, CFI/TLI = 1.00/0.99. Path coefficients are presented in Fig. 2. Being overprotective at T2 was predicted by peer difficulties at T1, and being overprotective at T1 predicted increased internalizing problems at T2 (p < 0.05); the opposite directions of effects were not significant. Examining within-time associations, being overprotective was positively associated with peer difficulties at T2 (p < 0.05). Regarding covariates, adolescent gender predicted being overprotective (T1: B = 0.35, p < 0.01), internalizing problems (T1: B = 0.08, p < 0.05), positive friendship quality (T1: B = 0.43, p < 0.001), and peer difficulties (T1: B = −0.33, p < 0.001). School was associated with positive friendship quality (T1: B = −0.15, p < 0.001; T2: B = −0.06, p < 0.01). Finally, maternal overprotection was associated (within-time points) with peer-nominated overprotection (T2: B = 0.19, p < 0.01), internalizing problems (T1: B = 0.18, p < 0.01), and peer difficulties (T1: B = 0.14, p < 0.05).

Discussion

As youth’s friends become closer and more influential during early adolescence, specific features that foster this closeness and reliance might carry unintentional negative consequences. Evidence that overprotection might be one such friendship feature was found in two prior quantitative studies of adolescent and emerging adult friendships (Etkin & Bowker, 2018; Etkin et al., 2022). The present study extends this past research by examining bidirectional associations between overprotection – including being overprotected and overprotective – and psychosocial adjustment, providing new information about friendship processes and how they contribute to adolescent development and psychopathology (Sameroff & Mackenzie, 2003). Results were partially in-line with initial hypotheses, but some unexpected findings also emerged, which together make novel contributions to the friendship literature and suggest a new and potentially developmentally significant friendship feature deserving of further inquiry.

Bidirectional Model of Being Overprotected

Consistent with expectations, this study showed that peer difficulties contributed to increases in friend overprotection over time. Difficulties like rejection and victimization are easily observable and may promote overprotection by friends, as rejected and victimized adolescents might appear vulnerable and in need of help. Although it was expected that internalizing problems would, like peer difficulties, lead to increases in adolescents’ experience of being overprotected, internalizing problems predicted decreases in friend overprotection over time. This unexpected finding may be explained by the Interpersonal Theory of Depression (Coyne, 1976). Adolescents with internalizing problems tend to develop negative cognitive biases and are prone to perceiving others as uncaring or unhelpful. Additionally, individuals with internalizing problems often excessively seek support from others in ways that push them away and impair their relationships. In this study, internalizing problems may be linked with decreased friend overprotection through similar mechanisms, although future research would be needed to test this. Future research is also needed to test why being overprotected did not contribute to increased peer problems or internalizing difficulties; longer term studies with additional time points might be especially helpful, especially given the high stability of these variables in this study (Bs = 0.71–0.96, ps < 0.001).

Regarding the hypothesized positive trade-off, results showed that being overprotected predicted decreases in positive friendship quality over time, and positive friendship quality did not predict increases in being overprotected. As in prior studies of friend overprotection, which only examined concurrent associations (Etkin & Bowker, 2018; Etkin et al., 2022), there were significant, positive within-time associations with positive friendship quality in this study (Bs = 0.53–0.56, ps < 0.001). Taken together, this pattern of results suggests that being overprotected is perceived favorably and associated with other positive provisions in the short term, but that it may erode these positive aspects of the friendship over time. This may be especially likely given the timing of this study; adolescents may perceive having an overprotective friend as helpful in the beginning of the school year (T1) when there is significant change, but as the year progresses (T2) and less help is needed, this behavior may become viewed as intrusive. In addition, it is plausible that being overprotected by a friend may interfere with feelings of equality, reciprocity, and autonomy support that are critical for fostering positive outcomes in adolescent friendships (Sullivan, 1953; Ryan & Deci, 2000). While additional research is needed to test this idea, several studies show that friendships lacking in autonomy support suffer from reduced quality and longevity (Deci et al., 2006; Demir et al., 2011), and in one study, reduced friend autonomy support suppressed the otherwise positive concurrent association between friend overprotection and positive friendship quality (Etkin et al., 2022). Future research examining adolescents’ attributions of friend overprotection may also help explain this pattern of findings, especially in light of theory and research showing that adolescents’ attributions of friend and peer behaviors explain variability in their psychological adjustment (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Bowker et al., 2007).

Bidirectional Model of Being Overprotective

The second set of hypotheses addressed, for the first time, the predictors and consequences of being overprotective of one’s friends. The construct of being overprotective was assessed in this study with a newly developed peer nomination item. In line with hypotheses, being overprotective predicted increased internalizing symptoms over time. Although this finding is novel, numerous studies show that being overly empathetic or caring toward others, including friends, can increase the risk for internalizing problems during adolescence (e.g., Champion et al., 2009; Tone & Tully, 2014). The present findings are unique, however, in that they provide initial evidence that being overprotective of friends may similarly cause an emotional burden that takes a toll on personal well-being. Future research will be needed to examine specifically why this is the case, but it is likely that acting in overprotective ways heightens one’s attention to potential threats and negativity, contributing to feelings of depression and anxiety. It is noteworthy that the opposite direction of effects was not found, suggesting that adolescents do not become overprotective due to feeling depressed or anxious.

Other factors might instead encourage adolescents to engage in overprotection, such as peer difficulties. Indeed, in this study, it was found that peer difficulties predicted increases in being overprotective. Adolescents who experience peer difficulties themselves may become more protective of their friends to keep them from suffering a similar fate, or to prevent the loss of any friendships – which are likely particularly important for those struggling with the larger peer group (Bowker & Weingarten, 2022). Unlike peer difficulties, however, positive friendship quality was not associated with being overprotective in either direction, suggesting that being overprotective of friends may have different implications at the dyadic and group levels of social complexity. Additional research is warranted to better understand these complex internalizing and peer risks and rewards of being overprotective of friends during adolescence.

The Role of Gender

Findings suggested that bidirectional associations between friend overprotection and psychosocial variables did not vary by adolescent gender. This is consistent with past research showing that associations between friendship features and adjustment tend to be similar across genders, even though girls consistently endorse higher levels of friendship qualities such as closeness and emotional disclosure (Rose & Asher, 2017). In this study, girls did report higher levels of overprotection than boys, both in terms being the overprotectee and overprotector. This may be because girls tend to value and excel at tasks related to helping (e.g., providing verbal support and reassurance; Rose & Asher, 2017), and many of the FOS-R items may reflect this (e.g., warning friends about possible risks, expressing worry about friends’ behaviors, encouraging friends to stay away from risky scenarios). The fact that girls were also found to be viewed by peers as more overprotective than boys offers additional support for this idea, although this finding may also be shaped by gender norms that guide perceptions. As the study of overprotection continues, it will be fruitful to see if there are specific, and observable, ways that boys and girls differ in terms of overprotection.

Limitations and Future Directions

A primary limitation of this study was the novel assessment of friend overprotection. The FOS-R was revised from a measure with evidence of good psychometric properties (Etkin et al., 2022), and was found to be internally consistent in this study. A confirmatory factor analysis and other procedures (e.g., examining associations with related and unrelated variables, such as friend control, Updegraff et al., 2004) are needed, however, to validate the FOS-R. Being overprotective of friends was also assessed with a new peer nomination item, which similarly requires validation in future studies. Single item peer nomination assessments are considered reliable given the use of multiple reporters (Coie et al., 1982). However, it is possible that some of the null and unexpected findings in this study involving both types of overprotection variables might be due to potential validity issues. Further, several study hypotheses were informed by past research on friend overprotection, which also raises the possibility that some of the unexpected findings in this study might be due to the new/different assessments used. In addition to reconciling these differences, future research may also consider developing additional measures, including a self-report measure of being overprotective and a behavior observational rating system of friend overprotection.

Another measurement-related limitation was the low reliabilities of the physical and relational victimization scales, which warrants caution in interpreting findings with these scales. Findings may have been further impacted by the fact that there were school differences on several variables, including the FOS-R. While the decision to focus on adolescent-level outcomes informed the use of adolescent-level analysis (rather than nested analysis; similar to Hamm et al., 2011), future studies should evaluate whether similar findings emerge when the nested data structure is reflected in the analyses. It could also be that unmeasured school-related variables may have changed or explained some results, if such measures had been included in this study (e.g., school climate and connectedness; Batanova & Loukas, 2012).

Scholarship on friend overprotection could be extended to additional populations and contexts. Perhaps internalizing difficulties would elicit overprotection in clinical populations, in which difficulties are more severe or evident. It is also possible that certain adolescents elicit overprotection due to other individual differences (e.g., low social or coping skills; low self-esteem or efficacy) or interpersonal processes that were not assessed in this study (e.g., excessive reassurance-seeking, social surrogacy, conversational self-focus; Markovic & Bowker, 2015; Prinstein et al., 2005; Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009). Future studies could also investigate whether friend overprotection functions as a moderator of associations between peer problems and internalizing symptoms, similar to other friendship quality research (e.g., Hodges et al., 1999).

Although the nonsignificant association between the FOS-R and overprotection peer nomination item in this study suggests adolescents are not at once overprotected and overprotective, the possibility that these two overprotection experiences are related, perhaps for certain youth in certain contexts, should not be overlooked. Examining associations with variables such as empathy, anxiety sensitivity, conflict, and jealousy could also help differentiate between those youth who are overprotective versus overprotected (e.g., jealousy may predict being overprotective but not overprotected; Parker et al., 2005). Finally, although not a main question of interest, it is notable that maternal overprotection was associated with friend overprotection, and predicted increases in being overprotected over time. Examining overprotection and its impact on adjustment across interpersonal contexts may also be an important direction with potential implications for demonstrating continuity in relationship processes during adolescence (e.g., Hodges et al., 1999).

Conclusion

Overprotection has received scant attention in research on friendships, and never before in a prospective and bidirectional study. Findings of this study showed that: (1) being overprotected by one’s friend is predicted by peer difficulties (positively) and internalizing problems (negatively), and contributes to decreases in positive friendship quality; and (2) being overprotective of one’s friends is predicted by peer difficulties and contributes to internalizing problems. These findings are novel and significant in their suggestion that overprotective behaviors ought not be neglected in the study of young adolescent friendships. Positive trade-offs were not found in the longitudinal analyses, but the findings do suggest that friendship researchers may do well to look beyond the most commonly studied friendship features (e.g., closeness) and consider new friendship features and processes, like overprotection, which may help to explain when and why friendships positively and negatively impact youth. If replicated, the findings may also set the stage for future intervention and prevention efforts with youth who are struggling to form or maintain friendships.

References

Bagwell, C. L., Bowker, J. C., & Asher, S. R. (2021). Back to the dyad: Future directions for friendship research. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 67(4), 457–484.

Bagwell, C. L., & Bukowski, W. M. (2018). Friendship in childhood and adolescence: Features, effects, and processes. In W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 371–390). New York, NY, The Guilford Press.

Batanova, M. D., & Loukas, A. (2012). What are the unique and interacting contributions of school and family factors to early adolescents’ empathic concern and perspective taking? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 1382–1391.

Berndt, T. J., & McCandless, M. A. (2009). Methods for investigating children’s relationships with friends. In K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski & B. Laursen (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 63–81). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Birmaher, B., Brent, D. A., Chiappetta, L., Bridge, J., Monga, S., & Baugher, M. (1999). Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(10), 1230–1236.

Bowker, J. C., Rubin, K. H., Rose-Krasnor, L., & Booth-LaForce, C. (2007). Good friendships, bad friends: Friendship factors as moderators of the relation between aggression and social information processing. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 4(4), 415–434.

Bowker, J. C., & Raja, R. (2011). Social withdrawal subtypes during early adolescence in India. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9461-7.

Bowker, J. C., & Weingarten, J. (2022). Temporal approaches to the study of friendship: Understanding the developmental significance of friendship change during childhood and adolescence. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 63, 249.

Bukowski, W. M., Hoza, B., & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the Friendship Qualities Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407594113011.

Champion, J. E., Jaser, S. S., Reeslund, K. L., Simmons, L., Potts, J. E., Shears, A. R., & Compas, B. E. (2009). Caretaking behaviors by adolescent children of mothers with and without a history of depression. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014978.

Chango, J. M., Allen, J. P., Szwedo, D., & Schad, M. M. (2015). Early adolescent peer foundations of late adolescent and young adult psychological adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25(4), 685–699.

Cillessen, A. N. (2009). Sociometric methods. In K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski & B. Laursen (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 82–99). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557.

Coyne, J. C. (1976). Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85, 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.85.2.186.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological bulletin, 115(1), 74.

Deci, E. L., La Guardia, J. G., Moller, A. C., Scheiner, M. J., & Ryan, R. M. (2006). On the benefits of giving as well as receiving autonomy support: Mutuality in close friendships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205282148.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2014). Autonomy and need satisfaction in close relationships: Relationships motivation theory. Human motivation and interpersonal relationships: Theory, research, and applications, 53-73.

Demir, M., & Davidson, I. (2013). Toward a better understanding of the relationship between friendship and happiness: Perceived responses to capitalization attempts, feelings of mattering, and satisfaction of basic psychological needs in same-sex best friendships as predictors of happiness. Journal of happiness studies, 14, 525–550.

Demir, M., Özdemir, M., & Marum, K. (2011). Perceived autonomy support, friendship maintenance, and happiness. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 145, 537–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.607866.

Etkin, R. G., & Bowker, J. C. (2018). Overprotection in adolescent friendships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 64, 347–375. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.64.3.0347.

Etkin, R. G., Bowker, J. C., & Simms, L. J. (2022). Friend overprotection in emerging adulthood: associations with autonomy support and psychosocial adjustment. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 183(2), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2021.2012640.

Hamm, J. V., Farmer, T. W., Dadisman, K., Gravelle, M., & Murray, A. R. (2011). Teachers’ attunement to students’ peer group affiliations as a source of improved student experiences of the school social–affective context following the middle school transition. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(5), 267–277.

Hartup, W. W. (1995). The three faces of friendship. Journal of Social and personal Relationships, 12(4), 569–574.

Hodges, E. E., Boivin, M., Vitaro, F., & Bukowski, W. M. (1999). The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 35, 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.94.

Hodges, E. E., Finnegan, R. A., & Perry, D. G. (1999). Skewed autonomy-relatedness in preadolescents’ conceptions of their relationships with mother, father, and best friend. Developmental Psychology, 35, 737–748. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.3.737.

Johnson, J. G., Harris, E. S., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2002). The Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00333-.

Jones, L. B., Hall, B. A., & Kiel, E. J. (2021). Systematic review of the link between maternal anxiety and overprotection. Journal of affective disorders, 295, 541–551.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Maccoby, E. E. (1990). Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American psychologist, 45(4), 513.

Markovic, A., & Bowker, J. C. (2015). Social surrogacy and adjustment: Exploring the correlates of having a ‘social helper’ for shy and non-shy young adolescents. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 176, 110–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2015.1007916.

Markovic, A., & Bowker, J. C. (2017). Friends also matter: Examining friendship adjustment indices as moderators of anxious-withdrawal and trajectories of change in psychological maladjustment. Developmental Psychology, 53(8), 1462.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & von Brakel, A. (2003). Assessment of anxious rearing behaviors with a modified version of ‘Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran’ questionnaire for children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 25, 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025894928131.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998). Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. 2017.

Parker, J. G., Low, C. M., Walker, A. R., & Gamm, B. K. (2005). Friendship jealousy in young adolescents: Individual differences and links to sex, self-esteem, aggression, and social adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 41, 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.235.

Prinstein, M. J., Borelli, J. L., Cheah, C. L., Simon, V. A., & Aikins, J. W. (2005). Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676.

Rapee, R. M. (2009). Early adolescents’ perceptions of their mother’s anxious parenting as a predictor of anxiety symptoms 12 months later. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 1103–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9340-2.

Rose, A. J. (2021). The costs and benefits of co‐rumination. Child Development Perspectives, 15(3), 176–181.

Rose, A. J., & Asher, S. R. (2017). The social tasks of friendship: Do boys and girls excel in different tasks. Child Development Perspectives, 11, 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12214.

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 98–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68.

Sameroff, A. J., & Mackenzie, M. J. (2003). Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology, 15(3), 613–640.

Selig, J. P., & Little, T. D. (2012). Autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data. In B. Laursen, T. D. Little, N. A. Card, B. Laursen, T. D. Little & N. A. Card (Eds.), Handbook of developmental research methods (pp. 265–278). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Schwartz-Mette, R. A., & Rose, A. J. (2009). Conversational self-focus in adolescent friendships: Observational assessment of an interpersonal process and relations with internalizing symptoms and friendship quality. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28, 1263–1297. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2009.28.10.1263.

Smith, R. L., & Rose, A. J. (2011). The “cost of caring” in youths’ friendships: Considering associations among social perspective taking, co-rumination, and empathetic distress. Developmental Psychology, 47(6), 1792.

Sroufe, L. A., & Rutter, M. (1984). The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child development, 17-29.

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton.

Thomasgard, M., & Metz, W. P. (1993). Parental overprotection revisited. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 24, 67–80.

Tone, E. B., & Tully, E. C. (2014). Empathy as a “risky strength”: A multilevel examination of empathy and risk for internalizing disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 1547–1565. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414001199.

Updegraff, K. A., Helms, H. M., McHale, S. M., Crouter, A. C., Thayer, S. M., & Sales, L. H. (2004). Who’s the Boss? Patterns of Perceived Control in Adolescents’ Friendships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000037633.39422.b0.

Woods, S., Done, J., & Kalsi, H. (2009). Peer victimisation and internalising difficulties: The moderating role of friendship quality. Journal of Adolescence, 32(2), 293–308.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the adolescents and schools that participated in this research. The authors also thank Drs. Jamie Ostrov, Leonard Simms, Lora Park, and Samuel Meisel, for their consultation on the development of this research.

Authors’ Contributions

RE conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, performed the measurement and statistical analysis, participated in the design and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript; JB participated in designing and coordinating the study, designing and interpreting the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Partial financial support for this study was received from the University at Buffalo Mark Diamond Research Fund.

Data Sharing Declaration

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University at Buffalo. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

All participants received informed parental consent to participate in this study. All participants also provided signed assent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Etkin, R.G., Bowker, J.C. Bidirectional Associations Between Friend Overprotection and Psychosocial Adjustment During Adolescence. J Youth Adolescence 52, 780–793 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01741-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01741-6