This study examined reciprocal associations among adolescents' negative feedback-seeking, depressive symptoms, perceptions of friendship quality, and peer-reported social preference over an 11-month period. A total of 478 adolescents in grades 6–8 completed measures of negative feedback-seeking, depressive symptoms, friendship quality, global-self-esteem, and social anxiety at two time points. Peer-reported measures of peer status were collected using a sociometric procedure. Consistent with hypotheses, path analyses results suggested that negative feedback-seeking was associated longitudinally with depressive symptoms and perceptions of friendship criticism in girls and with lower social preference scores in boys; however, depressive symptoms were not associated longitudinally with negative feedback-seeking. Implications for interpersonal models of adolescent depression are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Recent research in the social developmental and clinical literatures has revealed a tendency for some individuals to solicit negative feedback and criticism from others in close interpersonal relationships. In the clinical literature, “negative feedback-seeking” is considered to be a potential predictor of depressive symptoms, though this has been studied almost exclusively among adults (e.g., Joiner, 1995). Recent work in the developmental literature suggests that feedback-seeking also may have important implications for identity development and the formation of an adaptive self-concept (Cassidy, Ziv, Mehta, & Feeney, 2003). Although both literatures offer complementary perspectives, a theoretical and empirical integration of these ideas previously has not been offered.

Feedback-seeking behavior often is interpreted through the perspective of self-verification theory. The basic premise underlying self-verification theory (Swann, 1983, 1987, 1990), which extant research findings support, is that individuals seek to maintain “cognitive consistency” by selectively soliciting (Cassidy et al., 2003; Giesler, Josephs, & Swann, 1996; Swann & Read, 1981a, 1981b; Swann, Wenzlaff, Krull, & Pelham, 1992; Swann, Wenzlaff, & Tafarodi, 1992), attending to (Swann & Read, 1981a), recalling (Swann & Read, 1981a), and believing (Swann, Griffin, Predmore, & Gaines, 1987) feedback from others that confirms their self-concept (Joiner, 1995). From a developmental perspective, this behavior also likely serves multiple functions that are relevant to the transition to adolescence. Feedback-seeking is consistent with youths' normative developmental tendency to utilize interpersonal experiences as a reflected appraisal of self-worth (Felson, 1985). This behavior also offers specific opportunities for youth to solicit self-relevant information from valued others in the peer context, reflecting and contributing to increases in the frequency and quality of peer interactions during adolescence (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987). The goals of feedback-seeking also are relevant to self-development tasks that are central to adolescence. Presumably, youth who have established the rudiments of a positive self-concept will be most likely to process social information and solicit interpersonal responses from others in a manner that continues to confirm and enhance their favorable self-image.

However, clinical science has suggested important individual differences in feedback-seeking, suggesting that aberrations in this normal developmental behavior may be indicative of maladaptive developmental processes and may present risks for the onset or exacerbation of depressive symptoms. Specifically, it has been hypothesized that the need for cognitive consistency is retained even when individuals possess a negative self-concept (Joiner, 1995; c.f., Alloy & Lipman, 1992; Hooley & Richters, 1992). Individuals with low self-concepts or depression thus will be likely to engage in interpersonal behaviors that are aimed to verify negative self-beliefs and may contribute to negative interpersonal interactions. Some empirical support has amassed to support these ideas. Findings indicate that adults with a negative self-concept report higher levels of relationship satisfaction when relationships are self-verifying (i.e., negative feedback is provided) than when individuals' negative self-concept is challenged (Swann, Hixon, & de la Ronde, 1992; Swann, Wenzlaff, Krull, 1992). Research also suggests that individuals with negative self-concepts justify partner choice in an interaction task based on self-verification concerns (Swann, Stein-Seroussi, & Giesler, 1992), lending preliminary support to the idea that the receipt of feedback consistent with an individual's self-concept is important even for individuals with low self-concepts. These ideas have important, yet previously untested implications for understanding maladaptive development in adolescents.

The current study was designed to examine three study hypotheses. First, we examined whether adolescents' depressive symptoms indeed were associated prospectively with a tendency to solicit negative feedback about themselves. A reciprocal, longitudinal association was predicted as a second hypothesis suggesting that adolescents' negative feedback-seeking would be associated longitudinally with later depressive symptoms. Third, it was hypothesized that negative feedback-seeking would be associated prospectively with declines in adolescents' group and dyadic peer relations. In addition, we attempted to evaluate the symptom specificity of negative feedback-seeking by examining discriminant associations with social anxiety. The justification for each study hypothesis is discussed below.

The current longitudinal study offered an important opportunity to examine feedback-seeking behavior among adolescents. A first hypothesis reflected theoretical predictions regarding depressive symptoms as a predictor of negative feedback-seeking. Although past studies have revealed concurrent associations between negative feedback-seeking and depressive symptoms (Cassidy et al., 2003; Joiner, Katz, & Lew, 1997; Swann, Wenzlaff, Krull, 1992; Swann, Wenzlaff, & Tafarodi, 1992), no longitudinal data are currently available to indicate that depressive symptoms are associated prospectively with increases in negative feedback-seeking over time. Thus, an initial goal of this longitudinal study was to examine depressive symptoms as a predictor of adolescents' negative feedback-seeking. To examine developmental changes, this hypothesis was examined among youth at the beginning of the adolescent transition over approximately a 1-year period.

Second, because individuals who engage in negative feedback-seeking will be involved in interpersonal relationships that may ultimately yield information to verify their negative self-concept, negative feedback-seeking should be associated longitudinally with an exacerbation of depressive symptoms. Prior investigations examining negative feedback-seeking as a prospective predictor of depressive symptoms have been conducted almost exclusively among adults, yielding mixed support. In short-term longitudinal studies (e.g., 5 weeks), no main effect of negative feedback-seeking on later depressive symptoms has been revealed (Joiner, 1995; Pettit & Joiner, 2001a, 2001b); however, there is some evidence to suggest that negative feedback-seeking may be associated longitudinally with adults' depressive symptoms when combined with negative experiences (e.g., interpersonal rejection, Joiner, 1995; poor academic performance, Pettit & Joiner, 2001a).

No longer-term longitudinal studies of negative feedback-seeking have been reported nor has prior longitudinal work been conducted with adolescents. Cross-sectional examinations have revealed associations between negative feedback-seeking and depressive symptoms in both community-based (Cassidy et al., 2003) and psychiatric inpatient samples of youth (Joiner et al., 1997). Thus, a second goal of the current study was to examine the longitudinal association between negative feedback-seeking and subsequent depressive symptoms among adolescents. Negative feedback may have particularly potent implications for adolescent depressive symptoms, especially when feedback pertains to attributes that are relevant to values at this developmental stage, such as attractiveness and relational self-worth (Harter, Waters, & Whitesell, 1998). Associations were examined over the course of a 1-year time interval in consideration of the relatively stable peer environment and duration of time needed to capture changes in social-psychological functioning within this adolescent cohort.

Based on research suggesting a greater prevalence of depressive symptoms and greater reactivity to interpersonal stressors among girls, gender was examined as a moderator of the association between negative feedback-seeking and depressive symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994; Rudolph, 2002). No prior study among youth or adults has examined gender as a potential moderator of longitudinal associations between feedback-seeking and depressive symptoms.

Third, it was anticipated that negative feedback-seeking might have deleterious and ironic implications for the quality of interpersonal relationships and the way in which individuals are perceived by others. Although negative feedback-seeking offers individuals verification of their self-concept, it also promotes a dynamic in which negative or critical interpersonal feedback is communicated within a relationship. This may have important implications for interpersonal functioning, as well as further indirect consequences for depression and self-concept. Thus, a third goal of this investigation was to offer data on the potential interpersonal consequences of negative feedback-seeking. Specifically, this study examined whether negative feedback-seeking behavior predicted adolescents' perceptions of the quality of their best friendship after controlling for associations with depressive symptoms. Friendship quality was examined to reflect the interpersonal context in which negative feedback behavior is most likely to occur. Specifically, adolescents' perceptions of criticism within their best friendship were examined in light of past findings regarding the importance of perceived criticism as the single best predictor of depression relapse among adults (Hooley & Teasdale, 1989).

Negative feedback-seeking also may be associated with peer relations at the group level. Specifically, adolescents who engage in negative interpersonal behaviors such as negative feedback-seeking may be less well liked by peers and experience higher levels of peer rejection over time. Using peer-reported measures of peer acceptance/rejection, this hypothesis also was examined longitudinally in this study.

In addition to the examination of these three main hypotheses, a fourth goal of this investigation was to address the specificity of associations among negative feedback-seeking, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms. A predominant critique within this literature has been the assertion that negative feedback-seeking may simply represent a manifestation of anxiety symptoms (e.g., Joiner et al., 1997). In support of this argument, a substantial body of research suggests not only that depressive and anxiety symptoms often co-occur (e.g., Kovacs, 1996), but also that anxiety may be a developmental precursor to depressive symptoms during the adolescent transition (Reinherz, Stewart-Berghauer, Pakiz, & Frost, 1989; Rohde, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1991). Thus, it may be that unique associations between negative feedback-seeking and depressive symptoms are merely mimicking established associations between symptoms of depression and anxiety, rather than elucidating a unique interpersonal mechanism of depression.

Thus, as a conservative test of the association between depressive symptoms and negative feedback-seeking, adolescents' symptoms of social anxiety were controlled in all analyses. Social anxiety was selected based on conceptual overlap pertaining to interpersonal concerns. Recent research also suggests that social anxiety is likely distinct from other anxiety difficulties and appears to be most strongly related to depression (Krueger, 1999; Lahey et al., 2004; Mineka Watson, and Clark, 1998; Vollebergh et al., 2001).

The hypotheses examined in the current investigation primarily utilized adolescents' own reports of their behaviors, symptoms, and perceptions of relationships. To offer a stringent examination of study hypotheses, it was important to consider that apparent effects of negative feedback-seeking might represent an actual effect of adolescents' low self-esteem rather than these unique interpersonal behaviors. Thus, in addition to the covariates mentioned above, adolescents' global self-worth was controlled in analyses for each study hypothesis.

METHOD

Participants

Participants included 478 students (51% female) in grades 6 (33.3%), 7 (30.3%), and 8 (36.4%). All participants were between the ages of 11 and 14 years, M = 12.70, SD = 0.95. The students were recruited from a suburban middle-class middle school. According to school records, 11% of the children qualified for free or reduced-price lunch. The ethnic composition of the sample was 87% Caucasian-American, 4% Asian-American, 2% African-American, 2% Latino-American, and 6% from multi-ethnic backgrounds.

Participants were examined at two time points approximately 11 months apart. All sixth to eighth grade students attending the middle school at Time 1 were recruited for participation in the study. Consent forms were returned by 92% (n = 784) of families; of these, 80% of parents gave consent for their child's participation (n = 627, 74% of total recruited population). Data were missing from a total of 44 students, due to absenteeism (n = 10), incomplete responses (n = 30), and refusal to participate (n = 4). The final sample therefore included 580 participants at Time 1. Of these, a total of 478 (83%) participants were available for testing 11 months later (i.e., Time 2). Study attrition was due to relocation (n = 36), incomplete data (n = 54), absenteeism (n = 7), and refusal to continue with the study (n = 5). Attrition analyses revealed no significant differences on study variables between participants with and without available data at Time 2. Hypotheses were examined for participants with complete data for all study variables (n = 478) in the current investigation.

Measures

Negative Feedback-Seeking

The Feedback-Seeking Questionnaire (Swann et al., 1992), modified by Joiner and colleagues (1997) for use with adolescents and children, presents respondents with four lists of questions corresponding to four domains of self-worth (i.e., social competency, academic competency, athletic skills, and physical attractiveness). Each list includes four questions; two of these are worded as solicitations of positive feedback (e.g., “Am I fun to hang around with?”) and two are worded as solicitations of negative feedback (e.g., “My face looks sort of ugly, don't you think?”). An individual's score on the FSQ is equal to the number of negatively phrased questions endorsed.

The adult and adolescent versions of the FSQ have been used in many prior studies of feedback-seeking (e.g., Joiner, 1995; Joiner, Alfano, and Metalsky, 1993; Joiner et al., 1997; Pettit & Joiner, 2001a, 2001b). Construct validity has been supported in past research through significant correlations with feedback-seeking behavior in experimental conditions and with responses on instruments assessing self-concept (Swann, Pelham, & Krull, 1989; Swann & Read, 1981a; Swann et al., 1992). In the current study, adolescents' responses on the FSQ also were significantly associated with adolescents' global self-worth, Time 1 r = .34; Time 2 r = .38, ps < .0001, and inter-item correlations within self-worth domains ranged from .36 to .68 at Time 1 and Time 2. Internal consistency rarely is reported for the FSQ (e.g., Joiner et al., 1997) because, like some measures of attributional style (e.g., Children's Attributional Style Questionnaire; Thompson, Kaslow, Weiss, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998), the FSQ offers a screening of cross-domain feedback-seeking behavior and it is theoretically expected that this behavior is domain-specific. Similar to past research that has revealed alphas in the moderate range (i.e., between .63 and .68; Joiner et al., 1993, 1997), internal consistency in the current study was modest (.51 and .53 at Times 1 and 2). Results also revealed moderate test–retest stability in this sample (r = .40, p < .001).

Depression

The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) consists of 27-items designed to assess the behavioral, cognitive, emotional, and physiological features of depression. Participants choose one of three statements that best describes their symptoms over the past 2 weeks (e.g., “I am sad once in a while, “I am sad many times,” and “I am sad all the time”). Responses are coded on a scale of 0–2, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The psychometric properties of the CDI have been reported in past work (Kovacs, 1992; Saylor, Finch, Spirito, & Bennett, 1984). Internal consistency in this sample was adequate (α = .88 at both time points).

Social Anxiety

The Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A; La Greca & Lopez, 1998), adapted from the Social Anxiety Scale for Children-Revised (La Greca & Stone, 1993), was designed to assess adolescents' subjective experience of social anxiety. The measure consists of 22 statements, including 18 social anxiety items (i.e., “It's easy for me to make friends”) and four filler items (i.e., “I like to draw”). The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 = “not at all”; 5 = “all the time”). La Greca and colleagues have provided data to support the psychometric properties of the SASC-R and SAS-A (La Greca & Lopez, 1998; La Greca & Stone, 1993). Internal consistency of the SAS-A in this sample was high (αs = .93 at both time points).

Global Self-Worth

The self-perception profile for adolescents (SPPA; Harter, 1988) assesses adolescents' judgments of competence or adequacy in different areas of self-concept. All subscales contain six items, and each item is coded with a score of 1–4; mean scores are computed with lower scores reflecting greater perceived competence. In this study, the Global Self-Worth subscale was included as a measure of adolescents' general self-esteem. Harter (1988) reported good internal consistency for these subscales (Cronbach's ranged from .74 to .93), as well as considerable support for the validity of these subscales. Internal consistency in the current sample was adequate, α = .82.

Friendship Perception

Participants completed subscales from the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI; Furman, 1998) to examine adolescents' perceived friendship quality. The NRI assesses several domains of positive and negative friendship quality (e.g., criticism, companionship, conflict, emotional support, nurturance, reliable alliance, etc.). Past research among adults suggests that depression relapse is associated specifically with the perception that others are critical of them (Hooley & Teasdale, 1989). Accordingly, this study utilized the three-item friendship criticism subscale of the NRI (“How often does this person point out your faults or put you down?”, “How often does this person criticize you?”, and “How often does this person say mean or harsh things to you?”), with alphas equal to .75 at Time 1 and .77 at Time 2. The NRI is widely regarded as a valid and reliable index of adolescents' friendship perceptions (Furman, 1998).

Peer Acceptance/Rejection

A sociometric peer nomination assessment was conducted to obtain a measure of adolescents' peer acceptance/rejection. Adolescents in this school were organized in academic teams, each roughly twice the size of a traditional academic classroom. Adolescents each were presented with an alphabetized roster of their academic teammates, and asked to select an unlimited number of peers that they “liked the most,” and “liked the least.” The order of alphabetized names on this roster was counterbalanced (e.g., Z through A) to control for possible effects of alphabetization on nominee selection. A sum of the number of nominations each child received for each item was computed and standardized within each academic team. A difference score between standardized “like most” and “like least” nominations was then computed and restandardized for a measure of social preference, with higher scores indicating greater peer acceptance and lower scores indicating greater peer rejection (Coie & Dodge, 1983). Using this procedure it was possible to obtain an ecologically-valid measure of peer acceptance/rejection that was not influenced by adolescents' self-report. Data from sociometric nominations are widely considered the most reliable and valid indices of acceptance and rejection among peers (Coie & Dodge, 1983).

Data Analysis Plan

In order to evaluate study hypotheses, a two-fold data analytic plan was undertaken. First, a series of hierarchical multiple regressions were utilized to examine specific hypotheses. In these analyses, we were interested in evaluating gender and grade as potential moderators, as well as three-way interactions (gender × grade × predictor). A path analysis next was conducted to examine hypotheses simultaneously, while controlling for all revealed associations.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table I includes means and standard deviations for all primary study variables. t-Tests revealed a significant gender difference in adolescents' reports of friendship criticism at Time 2, such that boys reported higher levels of best friends' criticism than did girls. No other significant gender differences were revealed.

Correlations also were computed to examine bivariate associations between study variables and stability over time (see Table II). Results suggested that higher levels of adolescents' negative feedback-seeking were significantly associated with higher levels of adolescents' depressive symptoms, social anxiety, and perceptions of friendship criticism. Significant associations between adolescents' depressive symptoms and social anxiety also were revealed. Correlations over time revealed moderate to high stability for each of the primary variables.

Preliminary Analyses: Hierarchical Multiple Regressions

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses initially were conducted to examine hypothesized longitudinal associations. An initial hypothesis examined depressive symptoms as a prospective predictor of adolescents' negative feedback-seeking. A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted using adolescents' negative feedback-seeking at Time 2 as a criterion variable. After controlling for Time 1 negative feedback on an initial step, R 2 = .15, p < .001, gender, global self-worth, and social anxiety were entered on a second step ΔR 2 = .05, p < .001, and Time 1 depressive symptoms were entered on a third step ΔR 2 = .01, p < .01. Results revealed unique effects for both higher levels of social anxiety, β = 0.13, p < .01, and depressive symptoms, β = 0.16, p < .001, as prospective predictors of higher levels of negative feedback-seeking over time. Analyses of two- and three-way interactions involving gender and grade revealed no significant effects.

A second study hypothesis pertained to the reciprocal, longitudinal association suggesting that negative feedback-seeking would be associated with depressive symptoms over time. A second hierarchical multiple regression was conducted using Time 2 depressive symptoms as a dependent variable. After controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms on an initial step, R 2 = .47, p < .001, gender, global self-worth, and social anxiety on a second step, ΔR 2 = .01, p < .05, and Time 1 negative feedback-seeking on a third step, ΔR 2 = .01, p < .05, results revealed significant unique effects for higher levels of social anxiety, β = 0.09, p < .05, and negative feedback-seeking, β = 0.09, p < .05, as prospective predictors of higher levels of depressive symptoms over time. Again, no interaction effects for gender, grade, or grade × gender were revealed.

A final hypothesis pertained to negative feedback-seeking as a longitudinal predictor of adolescents' peer relations, including their perceptions of friendship criticism and their acceptance/rejection among peers. This hypothesis was examined in two hierarchical regression models similar to those described above. In each model, the Time 2 measure of peer relations (i.e., peer acceptance/rejection or perceived friendship criticism) was entered as a criterion variable, the corresponding Time 1 peer relations variable was entered on an initial step, followed by covariates (i.e., gender, global self-worth, social anxiety, and depressive symptoms) on a second step, and negative feedback-seeking on a third step. For the longitudinal prediction of friendship criticism, the second step of predictors, ΔR 2 = .02, ns, did not explain a significant proportion of variance beyond initial levels of friendship criticism, R 2 = .05, p < .001. The addition of negative feedback-seeking did offer a significant contribution to the model, however, ΔR 2 = .01, p < .05, indicating that higher levels of this behavior were associated with increases in perceptions of criticism, β = 0.11, p < .05. For the prediction of peer acceptance/rejection, only higher levels of social anxiety, β = −0.14, p < .05 were significantly associated with lower levels of social preference (i.e., indicating peer rejection) over time. No gender or grade interaction effects were revealed.

Path Analyses

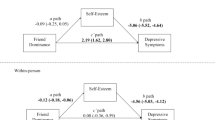

To examine the hypothesized associations more stringently while accounting for co-variation across both predictors and outcomes, and multiple observed associations, path analyses were conducted using full information maximum likelihood as implemented in Amos version 5.0.1 (Arbuckle, 1999). A multiple-group (by gender) initial path analysis included all six observed primary variables in the study (negative feedback-seeking, depressive symptoms, social anxiety, global self-worth, friendship criticism, and peer acceptance/rejection) at both Time 1 and Time 2, with autoregressive paths estimated for each between Times 1 and 2. Paths also were included for each hypothesized association, including the prediction of Time 2 negative feedback-seeking from Time 1 depressive symptoms, social anxiety, and global self-worth; the prediction of depressive symptoms from social anxiety and negative feedback-seeking; and the prediction of both friendship criticism and peer acceptance/rejection from negative feedback-seeking. All exogenous variables were allowed to covary. In concordance with past theory and research as well as results from correlation analyses, residual variance terms from Time 2, social anxiety and depressive symptoms also were allowed to covary. Because there was a theoretical basis to predict different patterns of associations across gender for each tested path, a multiple group analysis initially was conducted to yield separate, freely-varying estimates for boys and girls.

Satisfactory fit was revealed for this initial model, χ 2(74) = 166.85, p < .001; χ 2/df = 2.26; NFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04. Several modifications, each consistent with theory, were made to improve model fit. Improvement in the model was examined for each modification using a chi-square difference test. The residual term from Time 2 negative feedback-seeking was allowed to covary with residual terms for Time 2 depressive symptoms, χ 2 difference (2) = 28.9, p < .0001, and global self-worth, χ 2 difference (2) = 9.2, p < .01. Residual terms also were allowed to covary between depressive symptoms and global self-worth, χ 2 difference (2) = 9.4, p < .01, between depressive symptoms and friendship criticism, χ 2 difference (2) = 6.1, p < .05, and between social anxiety and friendship criticism, χ 2 difference (2) = 9.1, p < .01. In an effort to achieve a more parsimonious model, individual paths also were systemically constrained across gender, and chi-square difference tests were conducted for each model to determine whether the estimation of fixed path coefficients for boys and girls significantly improved model fit. In no cases was the model fit significantly different with fixed paths as compared to freely-varying paths; thus, all freely-estimated paths were retained.

Figure 1 displays the standardized estimates for statistically significant effects within this final path model. The modified model was a satisfactory fit to the data, χ 2(64) = 105.21, p = .001; χ 2/df = 1.64; NFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.03. Results revealed that among girls, Time 1 negative feedback-seeking was a significant predictor of Time 2 friendship criticism and depressive symptoms after accounting for its covariation with other exogenous predictors. Depressive symptoms, social anxiety, and global-self-worth were not significant longitudinal predictors of girls' negative feedback-seeking, however. Among boys, statistically significant paths revealed a marginally significant association between high levels of Time 1 negative feedback-seeking and low levels of Time 2 social preference (i.e., indicating peer rejection), p = .06, as well as a marginally significant association between Time 1 social anxiety and Time 2 negative feedback-seeking, p = .06. Time 1 social anxiety also was a statistically significant predictor of boys' Time 2 depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms and global self-worth were not significant longitudinal predictors of boys' negative feedback-seeking.

DISCUSSION

Interpersonal theories of depression suggest that some individuals engage in specific behaviors that can perpetuate depressive symptoms (e.g., Coyne, 1976; Hammen, 1991). To date, these ideas have been examined far more frequently among adults than youth. This study examined whether adolescents' negative feedback-seeking behavior was relevant to depressive symptoms and might be associated with adolescents' peer experiences.

Results offered mixed support of study hypotheses. An initial prediction pertained to the determinants of negative feedback-seeking. Consistent with self-verification theory, it was expected that adolescents' depressive symptoms would be associated with a tendency to seek negative feedback from peers, reflecting a desire to receive information that is consistent with a negative self-concept and/or depressed mood. However, the examination of a path model, controlling for the effects of all variables, indicated that depressive symptoms do not prospectively predict negative feedback-seeking within either gender. Rather, findings indicated that among boys, negative feedback-seeking was predicted only by social anxiety symptoms. Although this finding contrasts with preliminary work regarding the symptom specificity of negative feedback-seeking (e.g., Joiner et al., 1997), it is important to note that our results specifically highlight the role of social anxiety, rather than anxiety symptoms defined more broadly. In the context of growing evidence suggesting similarities in the presentation and mechanisms between social anxiety and depressive symptoms (Lahey et al., 2004), these findings offer an important contribution to the understanding of interpersonal mechanisms that may explain the evolution of negative appraisal fears to depressed mood.

Findings regarding negative feedback-seeking as a predictor of depressive symptoms were consistent with prior work (Cassidy et al., 2003; Joiner et al., 1997); however, the results from this study are the first to suggest that this association may be most relevant for girls. Notably, the significant results for girls remained even after controlling for adolescents' symptoms of social anxiety and low self-esteem, suggesting that negative feedback-seeking may be a unique predictor of girls' depressive symptoms (Kovacs, 1996; Reinherz et al., 1989; Rohde et al., 1991). Given girls' greater vulnerability to depressive symptoms and cognitions at this developmental period (Hankin & Abramson, 2001), as well girls' stronger relational orientation and greater reactivity to interpersonal stressors as compared to boys (Cyranowski, Frank, Young, & Shear, 2000; Rudolph & Hammen, 1999), it was anticipated that negative feedback-seeking would be an interpersonal behavior more frequent among girls and more relevant to their depressive symptoms. Findings indicated that while reports of negative feedback-seeking were no more frequent among girls, as has been reported in prior work (Cassidy et al., 2003; Joiner et al., 1997), it is only among girls that this interpersonal behavior prospectively predicts depressive symptoms.

In addition to the potential emotional consequences of negative feedback-seeking, this study also examined associations with peer relations, including adolescents' reports of friendship criticism and peers' reports of peer acceptance/rejection. The examination of associations between negative feedback-seeking and peer relations offers a preliminary opportunity to elucidate potential effects of individuals' behavior on their social environment. Consistent with a stress-generation model of depression (Hammen, 1991; Rudolph, 2002), which postulates that the interpersonal behavior of depressed individuals may ironically reify and confirm negative beliefs and fears about the social environment, results indicated that negative feedback-seeking was associated longitudinally with higher levels of perceived criticism from best friends among girls, and lower levels of peer-reported social preference among boys. Findings differ based on informant, and therefore should be interpreted cautiously. However, it is interesting to note that results generally suggest that negative feedback-seeking is specifically related to aspects of peer relationships that are most relevant for each gender; adolescent girls are particularly attuned to dyadic peer experiences whereas boys remain oriented to group-level peer relations. Importantly, both perceptions of criticism (Hooley & Teasdale, 1989) and lower levels of social acceptance (Panak & Garber, 1992) may offer risk for worsening of depressive symptoms.

Overall, results offered important preliminary evidence consistent with an interpersonal model of depression among adolescents. Findings may be useful for understanding the contribution of social behaviors in the development or maintenance of depression during the critical developmental period associated with increased prevalence. However, several unanticipated findings also emerged and some important caveats deserve consideration.

For instance, it should be noted that although reported findings reached statistical significance, the size of effects for negative feedback-seeking was quite modest. This may be due to several factors. Most strikingly, results revealed high stability of depressive symptoms across the two time points of this study, thus substantially reducing the proportion of unexplained variability in Time 2 depressive symptoms after controlling for initial levels. Second, to remain consistent with prior investigations (e.g., Joiner et al., 1997), negative feedback-seeking was examined using an established assessment instrument in order to produce results that could be directly compared to those found in prior investigations (e.g., Joiner et al., 1997) with youth and the accumulating body of research on negative feedback-seeking in adults; however, this measure has some important limitations. An instrument examining negative feedback-seeking behavior among significant others (e.g., parents, teachers) in addition to peers, or assessing a broader array of self-concept domains using multiple items for each, might reveal associations larger in magnitude (e.g., Cassidy et al., 2003).

Third, it also is important to note that negative feedback-seeking was examined as a sole interpersonal predictor; however, this behavior likely occurs in the context of several additional depression-related interpersonal behaviors that may offer incremental contributions in the prediction of depression (Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon, & Aikins, 2005). The actual frequency and contribution of negative feedback-seeking alone indeed may be relatively modest. Some have suggested that negative feedback-seeking behavior may be observed in the context of additional interpersonal behaviors (including positive feedback-seeking) in a manner that is significantly more complex than demonstrated in this initial longitudinal study among adolescents (Alloy & Lipman, 1992; Hooley & Richters, 1992). Lastly, this study included a community sample of adolescents to capture the onset of the depression–interpersonal rejection cycle; however, stronger effects may emerge when examining a sample with clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms. The use of a community-based sample also might explain the absence of gender differences reaching statistical significance in the overall prevalence of depressive symptoms.

Future research would benefit by addressing these limitations as well as some other important avenues for exploration. For instance, it would be useful to examine the effects of negative feedback-seeking on interpersonal functioning from additional perspectives (e.g., self- and other-report), including the individuals from whom negative feedback is sought. This approach might reveal important moderators of the association between seeking-behavior and seekers' subsequent emotional responses (i.e., depressed affect), as well as possible misperceptions of subsequent relationship quality. There is good reason to suspect that depressed individuals' perceptions of the quality of their best friendship might be erroneous (Daley & Hammen, 2002) but damaging nevertheless.

In addition, the current study employed a relatively homogenous sample of middle school children. Future research could contribute to the study of negative feedback-seeking and its interpersonal sequelae by employing more diverse samples as well as studying the relation among these variables during different developmental stages. Cultural studies of the manifestation of negative feedback-seeking behavior within peer groups of adolescents of varying demographic backgrounds also would be an interesting future direction for this line of research.

Lastly, future research using more than two time points would help to examine possible mediator or iterative models demonstrating longitudinal transactions between individuals' behavior and their interpersonal experiences.

Overall, findings from this study offer an important preliminary validation of interpersonal theories of depression as applied to youth, and an evaluation of several theoretically stringent predictions. Negative feedback-seeking may be one of many interpersonal behaviors that are exhibited more frequently among depressed or anxious adolescents that lead to exacerbations of depressed symptoms and negative peer relations. Findings are consistent with both self-verification and stress-generation theories of depression and provide an important avenue for cognitive-behavioral interventions, including skills training and restructuring.

REFERENCES

Alloy, L. B., & Lipman, A. J. (1992). Depression and selection of positive and negative social feedback: Motivated preference or cognitive balance? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 310–313.

Arbuckle, J. L. (1999). Amos (Version 4.0) [Computer Software]. Chicago: Smallwaters.

Buhrmester, D., & Furman, W. (1987). The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development, 58, 1101–1113.

Cassidy, J., Ziv, Y., Mehta, T. G., & Feeney, B. C. (2003). Feedback-seeking in children and adolescents: associations with self-perceptions, attachment representations, and depression. Child Development, 74, 612–628.

Coie, J. D., & Dodge, K. A. (1983). Continuities and changes in children's social status: A five-year longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 29, 261–282.

Coyne, J. C. (1976). Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry, 39, 28–40.

Cyranowski, J. M., Frank, E., Young, E., & Shear, M. K. (2000). Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: A theoretical model. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 21–27.

Daley, S. E., & Hammen, C. (2002). Depressive symptoms and close relationships during the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from dysphoric women, their best friends, and their romantic partners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 127–141.

Felson, R. B. (1985). Reflected appraisal and the development of self. Social Psychology Quarterly, 48, 71–78.

Furman, W. (1998). The measurement of children and adolescents' perceptions of friendships: Conceptual and methodological issues. In W. M. Bukowski, A. F. Newcomb, & W. W. Hartup (Eds.), The company they keep: Friendships in childhood and adolescence. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Giesler, R. B., Josephs, R. A., & Swann, W. B. Jr. (1996). Self-verification in clinical depression: The desire for negative evaluation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105, 358–368.

Hammen, C. (1991). Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 555–561.

Hankin, B. L., & Abramson, L. Y. (2001). Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 773–796.

Harter, S. (1988). Manual for the self-perception profile for adolescents. Denver: University of Denver.

Harter, S., Waters, P., & Whitesell, N. (1998). Relational self-worth: Differences in perceived worth as a person across interpersonal contexts among adolescents. Child Development, 69, 756–766.

Hooley, J. M., & Richters, J. E. (1992). Allure of self-confirmation: A comment on Swann, Wenzlaff, Krull, & Pelham. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 307–309.

Hooley, J. M., & Teasdale, J. D. (1989). Predictors of relapse in unipolar depressives: Expressed emotion, marital distress, and perceived criticism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98, 229–235.

Joiner, T. E. Jr. (1995). The price of soliciting and receiving negative feedback: Self-verification theory as a vulnerability to depression theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 364–372.

Joiner, T. E. Jr., Alfano, M. S., & Metalsky, G. I. (1993). Caught in the crossfire: Depression, self- consistency, self-enhancement, and the response of others. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 12, 113–134.

Joiner, T. E., Katz, J., & Lew, A. S. (1997). Self-verification and depression among youth psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 608–618.

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children's depression inventory manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Kovacs, M. (1996). The course of childhood-onset depressive disorders. Psychiatric Annals, 26, 326–330.

Krueger, R. F. (1999). The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 921–926.

La Greca, A. M., & Lopez, N. (1998). Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 83–94.

La Greca, A. M., & Stone, W. L. (1993). Social anxiety scale for children-revised: Factor structure and concurrent validity. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 22, 17–27.

Lahey, B., Applegate, B., Waldman, I. D., Loft, J. D., Hankin, B. L., & Rick, J. (2004). The structure of child and adolescent psychopathology: Generating new hypotheses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 358–385.

Mineka, S., Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1998). Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 377–412.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Girgus, J. S. (1994). The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 424–443.

Panak, W. F., & Garber, J. (1992). Role of aggression, rejection, and attributions in the prediction of depression in children. Development and Psychopathology, 4, 145–165.

Pettit, J. W., & Joiner, T. E. Jr. (2001a). Negative-feedback-seeking leads to depressive symptom increases under conditions of stress. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23, 69–74.

Pettit, J. W., &Joiner, T. E. Jr. (2001b). Negative life events predict negative feedback-seeking as a function of impact on self-esteem. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25, 733–741.

Prinstein, M. J., Borelli, J. L., Cheah, C. S. L., Simon, V. A., & Aikins, J. W. (2005). Adolescent girls' interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 114, 676–688.

Reinherz, H. Z., Stewart-Berghauer, G., Pakiz, B., Frost, A. K., et al. (1989). The relationship of early risk and current mediators to depressive symptomatology in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 942–947.

Rohde, P., Lewinsohn, P. M., & Seeley, J. R. (1991). Comorbidity of unipolar depression: II. Comorbidity with other mental disorders in adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 214–222.

Rudolph, K. D. (2002). Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 305, 3–13.

Rudolph, K. D., & Hammen, C. (1999). Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Development, 70, 660–677.

Saylor, C. F., Finch, A. J., Spirito, A., & Bennett, B. (1984). The Children's Depression Inventory: A systematic evaluation of psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52, 955–967.

Swann, W. B. Jr. (1983). Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the self. In J. Suls, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Social psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 2, pp. 33–66), Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Swann, W. B. Jr. (1987). Identity negotiation: Where two roads meet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1038–1051.

Swann, W. B. Jr. (1990). To be known or to be adored: The interplay of self-enhancement and self-verification. In E. T. Higgins & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition (Vol. 2., pp. 408–448). New York: Guilford.

Swann, W. B. Jr., Griffin, J. J., Predmore, S., & Gaines, B. (1987). The cognitive-affective crossfire: When self-consistency confronts self-enhancement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 881–889.

Swann, W. B. Jr., Hixon, J. G., & de la Ronde, C. (1992). Embracing the bitter “truth”: Negative self-concepts and marital commitment. Psychological Science, 3, 118–121.

Swann, W. B., Pelham, B. W., & Krull, D. S. (1989). Agreeable fancy or disagreeable truth? Reconciling self-enhancement and self-verification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 782–791.

Swann, W. B. Jr., & Read, S. J. (1981a). Acquiring self-knowledge: The search for feedback that fits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 1119–1128.

Swann, W. B. Jr., & Read, S. J. (1981b). Self-verification processes: How we sustain our self- concepts. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 17, 351–372.

Swann, W. B., Stein-Seroussi, A., & Giesler, R. B. (1992). Why people self-verify. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 392–401.

Swann, W. B. Jr., Wenzlaff, R. M., Krull, D. S., & Pelham, B. W. (1992). Allure of negative feedback: Self-verification strivings among depressed persons. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 293– 305.

Swann, W. B. Jr., Wenzlaff, R. M., & Tafarodi, R. W. (1992). Depression and the search for negative evaluations: More evidence of the role of self-verification strivings. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 314–317.

Thompson, M., Kaslow, N. J., Weiss, B., Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1998). Children's attributional style questionnaire–revised: Psychometric examination. Psychological Assessment, 10, 166– 170.

Vollebergh, W. A. M., Iedema, J., Bijl, R. V., de Graaf, R., Smit, F., & Ormel, J. (2001). The structure and stability of common mental disorders: The NEMESIS study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 597–603.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from NIMH (R01-MH59766) and the American Foundation of Suicide Prevention awarded to the second author. Special thanks are due to Charissa S. L. Cheah, Julie Wargo Aikins, Valerie Simon, Annie Fairlie, Robin M. Carter, Daryn David, Carrie Hommel, and Erica Foster for their assistance with data collection, as well as all of the adolescents and families who participated in this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Borelli, J.L., Prinstein, M.J. Reciprocal, Longitudinal Associations Among Adolescents' Negative Feedback-Seeking, Depressive Symptoms, and Peer Relations. J Abnorm Child Psychol 34, 154–164 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-005-9010-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-005-9010-y