Abstract

Purpose of Review

Morbid obesity and type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are both major public health problems. Bariatric surgery is a proven and effective treatment for these conditions; laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is currently the gold-standard treatment. One-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) is described as a simpler, safer, and non-inferior alternative to RYGB to treat morbid obesity. Concerning T2DM, experts of the OAGB procedure report promising metabolic results with good long-term remission of T2DM; however, heterogeneity within the literature prompted us to analyze this issue.

Recent Findings

OAGB has gained popularity given its safety and long-term efficacy. Concerning the effect of OAGB for the treatment of T2DM, most reports involve non-controlled single-arm studies with heterogeneous methodologies and a few randomized controlled trials. However, this available literature supports the efficacy of OAGB for remission of T2DM in obese and non-obese patients. Two years after OAGB, the T2DM remission and improvement rate increased from 67 to 100%. The results were improved and stable in the long term. The 5-year T2DM remission rate increased from 82 to 84.4%. OAGB is non-inferior compared with RYGB and even superior to other accepted bariatric procedures, such as sleeve gastrectomy and adjustable gastric banding.

Summary

OAGB is an efficient, safe, simple, and reversible procedure to treat T2DM. The literature reveals interesting results for T2DM remission in non-obese patients. High-level comparative studies are required to support these data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Morbid obesity and type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are both major public health problems [1••]. Obesity is a major risk factor for T2DM. Globally, 90% of T2DM patients are overweight [2•, 3]. Bariatric surgery has been proven effective at treating these conditions [1••, 4,5,6,7, 8••]; it has high efficacy at achieving long-term remission of T2DM and provides sustainable weight loss [1••, 4, 6, 8••, 9]. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is currently the gold-standard treatment [1••, 10, 11, 12••, 13–16, 54–59].

The immediate postoperative antidiabetic effect of RYGB is explained by reduced caloric intake within the first days after surgery, inducing upregulation of cell membrane insulin receptors, and duodenal exclusion, which results in neuro-hormonal signals and anti-incretin effects [10••, 11•, 12••]. Improved glucose tolerance is achieved by rapid entry of ingested nutrients into the distal small bowel, where L cells in the mucosa secrete incretin GLP-1 into the bloodstream. This effect leads to pancreatic beta cell hypertrophy and secretion of insulin. In long-term follow-ups, glycemic control is also associated with surgically induced weight loss [12••, 13,14,15]. At 1 year after surgery, Cummings et al. reported a 60% remission rate for T2DM (HbA1c < 6.0% without glucose-lowering drugs) after a RYGB [1••, 59], whereas Mingrone et al. reported a 42% remission rate (HbA1c < 6.5% without glucose-lowering drugs) at 5 years post-surgery [1••, 16].

Since 2001, mini-gastric bypass (i.e., one-anastomosis gastric bypass [OAGB]) has been described as an effective alternative to RYGB to treat morbid obesity and T2DM [17,18,19,20,21]. The significant glycemic control observed after OAGB is intuitively explained by the physiological similarities between these techniques, i.e., immediate postoperative reduction in caloric intake, durable weight loss, and duodenal bypass. Compared with a RYGB, the OAGB is technically simpler with only one omega-loop gastro-jejunal anastomosis [20, 22]. Numerous OAGB experts have reported promising metabolic results with significant remission rates for T2DM in the shorter and longer term [23••, 24, 25•, 26••, 27].

In 2011, the International Diabetes Federation stated that “simplicity” and “reversibility” of a metabolic procedure should be considered when treating T2DM [15]. These two technical characteristics are clearly met with the OAGB procedure. In contrast, sleeve gastrectomy (SG) is irreversible and RYGB is technically more difficult to perform and to reverse. These factors associated with the promising results from treating morbid obesity prompted us to study the efficacy of OAGB to treat T2DM.

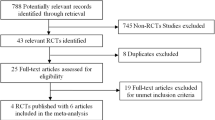

Review Method

A search of the literature on glycemic control and T2DM remission after an OAGB was performed using the MEDLINE database. The search included data from inception until April 2017. The search included both human and animal studies. The terms used were “mini-gastric bypass,” “single-anastomosis gastric bypass,” “one-anastomosis-gastric bypass,” “gastric bypass,” “omega-loop gastric bypass,” “diabetes,” and “type-2 diabetes mellitus.”

Results and Discussion

Glycemic Control After OAGB in Animals

Few reports on this topic were identified, and experimental OAGB models were only performed in rats [28••, 29]. The experimental literature showed that OAGB in rats improved the oral glucose tolerance test and glycemic control compared with a control group. Zubiaga et al. reported that the glucose tolerance test improved glycemic levels in rats with OAGB at all time periods (i.e., early 12 weeks; intermediate 16 weeks; later 20 weeks). Insulin levels were decreased significantly in all rats with OAGB, but glucagon levels paradoxically increased [28••]. GLP-1 and GIP increased in rats at all times but were only significantly different in the early group of GLP-1. Glycemic control after OAGB was independent of weight loss because all rats maintained their weight. This study reported surgically induced enhancement of pancreatic function mainly due to bypassing the duodenum, thus supporting Rubino’s theory that exclusion of the duodenum/proximal intestine and/or early entrance of food into the distal bowel improves glucose tolerance [12••, 13].

These experimental results in rats support the efficacy of OAGB to improve glycemic control. The consequent endocrinological effect after a proximal bowel bypass, as also found after bypass procedures in humans, produces substantial hormonal changes, including an increase in insulin-like growth factor-1 levels and decreases in leptin, insulin, and GIP levels even prior to body weight changes.

T2DM and OAGB in Humans

OAGB has gained popularity over the past few years given its safety and long-term efficacy [30, 31]. Concerning the available literature, OAGB appears to be non-inferior and potentially superior to other accepted bariatric procedures [32, 33, 34•]. OAGB is a particularly promising method for metabolic and anti-diabetic surgery. OAGB is simpler to perform than the gold-standard RYGB, with a shorter learning curve and easier reversal (if required) [35]. These criteria match the International Diabetes Federation definition for an appropriate metabolic surgical procedure.

Single-Arm OAGB Studies

A systematic review of non-controlled single-arm studies reported that OAGB was efficient and significantly improved T2DM in all reviewed studies [17, 18, 23••, 24, 25•, 27, 36, 37, 38••, 39, 40,41,42, 43, 44, 45]. Two years after OAGB, the T2DM remission or improvement rate increased from 67 to 100% [17, 18, 23••, 24, 25•, 27, 36, 37, 38••, 39, 40,41,42, 43, 44, 45, 46••, 47•]. Guenzi et al. [45] reported 82.5% T2DM control with a HbA1c < 6.5% after a mean follow-up of 26 months. The results improved over time and were stable over the long term. The 5-year T2DM remission rate increased from 82 to 84.4% [46••]. Carbajo et al. [38••] published a retrospective series in 2016 on 1200 OAGB patients with a long follow-up that exceeded 10 years. In the global series, they reported remarkable results with a 94% remission rate and a 6% improvement rate for T2DM. Due to a lack of published data, we do not know the specific remission rate for patients with greater than 10 years of follow-up, but Carbajo et al. concluded that both T2DM and impaired fasting glucose could be resolved or at least ameliorated.

More recently, Taha et al. [47•] published a study in 2017 on a retrospective series of 1520 OAGB patients, including 683 (44.9%) diabetic patients with a mean preoperative HbA1c of 9.6 ± 1.3%. In total, 472 patients were followed for 1 year and 361 patients were followed for 3 years. Mean postoperative HbA1c decreased by 5.7 ± 1.5 and 5.8 ± 0.9% at 1 and 3 years, respectively. Complete remission of T2DM was achieved in 397/472 (84.1%) patients. In contrast, 37 (7.8%) patients achieved partial remission and 33 (7%) experienced disease improvement.

All these promising results support the efficacy of OAGB to increase remission of T2DM in obese patients, but the major limitations of these studies are the low levels of evidence and the heterogeneous definitions used for T2DM remission and improvement given that some authors did not clearly report the methodology used to assess HbA1C levels.

OAGB Compared with RYGB

Only one controlled randomized trial has been published that compares OAGB with RYGB at 2 years [20]. The study did not identify any difference in metabolic syndrome remission at 2 years after an OAGB or a RYGB. After 5 years of follow-up, the same authors reported on a comparative but not randomized study, revealing enhanced remission of metabolic syndrome in the OAGB group [21]. These promising data were confirmed by a meta-analysis conducted by Quan et al. [46••]. An improved remission rate for T2DM after OAGB (93 vs. 77.6% for RYGB; p = 0.006) was reported [46••]. Once again, these results demonstrate the legitimacy of using OAGB to treat T2DM. In addition, OAGB is not inferior and is probably superior to the present gold-standard procedure.

OAGB Compared with Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding

Quan et al. [46••] conducted a meta-analysis on OAGB versus laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) and found a “marginally” higher remission rate for T2DM with OAGB compared with LAGB. However, only two studies were included in this meta-analysis and the heterogeneity of the data could have explained these conclusions. For experts of OAGB [18, 23••, 25•, 41], the long-term remission rates are clearly superior after OAGB compared with those of LAGB.

OAGB Compared with Sleeve Gastrectomy

Quan et al. reported better remission rates for T2DM after OAGB in their meta-analysis compared with SG in four significant studies (89 versus 76%, p = 0.0004) [46••]. Lee et al. reported a significantly reduced HbA1c at 5 years after OAGB compared with SG in a randomized prospective study [48•]. Moreover, Kular et al. reported a significantly better 5-year T2DM remission rate after OAGB (92 vs. 81%, P < 0.05) [49]. Musella et al. [26••] published an important multicenter European audit on 206 cases of T2DM in obese patients. At 1 year, OAGB was associated with significantly superior weight loss (p < 0.001) and T2DM remission compared with SG (85.4 vs. 60.9%; p < 0.001). In their conclusion, OAGB was a positive predictor for diabetes remission and significantly outperformed SG. Moreover, high baseline HbA1c, preoperative consumption of insulin or oral antidiabetic therapy, and T2DM duration > 10 years were negative factors [26••].

More recently, time until glycemic control postoperatively was investigated in a comparative observational study of bariatric surgeries led by Celik al. [50]. This study included 251 diabetic patients with a mean BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 and T2DM for ≥ 3 years, HBA1C > 7% for ≥ 3 months, and no significant weight change (> 3%) within the prior 3 months. Glycemic control (< 126 mg/dL) was obtained in the group that underwent a diverted SG with an ileal transposition on day 29 and those who underwent a mini-gastric bypass (or OAGB) on day 30. Patients with an SG did not achieve the target level within postoperative 30 days.

OAGB for Diabetic Patients with a BMI of < 35 kg/m2

According to Garcia et al. [51], an OAGB leads to resolution or improvement of T2DM in non-obese normal-weight patients. The best results were obtained for patients who have had diabetes for a few years without or with short-term use of insulin treatment and high C-peptide levels.

Moreover, a 7-year retrospective study reported by Kular et al. [52] demonstrated that OAGB provides good long-term control of T2DM in patients with class-I obesity (BMI < 35 kg/m2). The mean preoperative HbA1C level was 10.7%. After 1, 3, 5, and 7 years, mean HbA1C levels were 6.2, 5.4, 5.8, and 5.7, respectively. Although 22% of patients were using insulin preoperatively, none required insulin postoperatively for up to 7 years. Fasting C-peptide levels increased from 1.6 ng/mL prior to surgery to 2 ng/mL after surgery, and the post-prandial C-peptide concentration increased from 3.4 to 4.7 ng/mL, suggesting that OAGB improves beta cell function.

Conclusion

Despite the heterogeneity and the low level of evidence in the literature, OAGB appears to be a promising option for treating type-2 diabetes in obese and non-obese patients. Based on analyses of the available data with a low number of controlled randomized trial, OAGB represents a non-inferior (probably superior) and simpler alternative to the gold-standard treatment (RYGB) and interestingly seems to be superior to other accepted bariatric procedures, such as SG and LAGB, in treating type-2 diabetes.

These good results for weight loss and remission of T2DM can explain why OAGB is gaining popularity within the bariatric community. Although its metabolic efficacy cannot be analyzed separately from surgical risk (morbidity, mortality) and the benefit-risk balance, OAGB appears to be safer than RYGB during the postoperative course with a lower morbidity rate [20, 35].

Over the mid- to long-term, OAGB experts have reported low morbidity rates [20, 21, 23••, 25•, 40, 41]. However, a major controversy remains regarding the long-term theoretical risk of developing biliary reflux because the omega loop can induce direct passage of biliopancreatic juices into the gastric tube and perhaps the esophagus [53]. Despite this, no rigorous scientific study in human has analyzed prospectively biliary reflux and its attendant possible complications, such as esogastric cancer. To date, four cases of cancer secondary to OAGB have been reported: three were in the excluded stomach (unrelated to the surgical montage) and one was in the gastric pouch at several years after an “omega loop gastric bypass” (probably an old “Mason” gastric bypass) [53]. Because of the lack of reported incidence rates, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions regarding the imputability of biliary reflux. Other cases of cancer have been diagnosed after all bariatric surgical procedures such as sleeve gastrectomy (n = 1), gastric banding (n = 4), vertical-banded gastroplasty (n = 9), and RYGB (n = 14) [53]. An experimental study in obese rats that had undergone an OAGB did not show any pre-cancerous or cancerous lesions with unchanged expression of Barrett’s esophagus or esogastric carcinogenic-specific genes in the esophageal and gastric mucosae 4 months after surgery [29].

Given its promising metabolic results with the associated technical advantages and postoperative safety, it is now clear that OAGB will be recognized as a valid procedure and will be accepted worldwide when the question over biliary reflux is resolved by high-level and comparative studies. To date, no acceptable estimation of this risk (and its potential complications on the gastric and esophageal mucosa) has been established and an answer to this controversial issue is needed urgently.

Finally, as recommended by the International Diabetes Federation, a good metabolic procedure must be reversible and, once again, OAGB fits this need. OAGB is reversible by laparoscopy (while a sleeve gastrectomy is not reversible) and is easier to reverse compared to a RYGB.

In conclusion, OAGB is an efficient, safe, simple, and reversible procedure to treat type-2 diabetes mellitus and morbid obesity. The literature presents interesting results for remission of type-2 diabetes in non-obese patients. High-level comparative studies are required to support these data and eliminate doubts that remain concerning the long-term theoretical risk of biliary reflux.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Nguyen NT, Varela JE. Bariatric surgery for obesity and metabolic disorders: state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(3):160–9. Important review of bariatric surgery.

• Dixon JB, Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Rubino F. Bariatric surgery: an IDF statement for obese Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2011;28:628–42. Statement for the surgical treatment of type-2 diabetes.

Alberti KGMM, Zimmet P, Shaw J. International diabetes federation: a consensus on type 2 diabetes prevention. Diab Med. 2007;24:451–63.

Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Jensen MD, Pories WJ, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122:248–56.

Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–37.

Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg. 2013;23:427–36.

Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–93.

•• Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial—a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219–34. Prospective controlled study that proved the superiority of surgery.

Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—3-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2002–13.

•• Rubino F. Medical research: time to think differently about diabetes. Nature. 2016;533:459–61. Future of the research in diabetes treatment.

• Rubino F, Marescaux J. Effect of duodenal–jejunal exclusion in a non-obese animal model of type 2 diabetes: a new perspective for an old disease. Ann Surg. 2004;239:1–11. Important research.

•• Rubino F, Forgione A, Cummings DE, Vix M, Gnuli D, Mingrone G, et al. The mechanism of diabetes control after gastrointestinal bypass surgery reveals a role of the proximal small intestine in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Ann Surg. 2006;244:741–9. Mechanism of diabetes control after gastric bypass.

Rubino F, Gagner M, Gentileschi P, Kini S, Fukuyama S, Feng J, et al. The early effect of the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on hormones involved in body weight regulation and glucose metabolism. Ann Surg. 2004;240:236–42.

Rubino F, Gagner M. Potential of surgery for curing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 2002;236:554–9.

Dixon JB, Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Rubino F. Bariatric surgery: an IDF statement for obese type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2011;28:628–42.

Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Nanni G, et al. Bariatric-metabolic surgery versus conventional medical treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: 5 year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:964–73.

Rutledge R. The mini-gastric bypass: experience with the first 1,274 cases. Obes Surg. 2001;11:276–80.

Rutledge R, Walsh TR. Continued excellent results with the mini-gastric bypass: six-year study in 2,410 patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1304–8.

Lee WJ, Lin YH. Single-anastomosis gastric bypass (SAGB): appraisal of clinical evidence. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1749–56.

Lee WJ, Yu PJ, Wang W, Chen TC, Wei PL, Huang MT. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y versus mini-gastric bypass for the treatment of morbid obesity: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2005;242:20–8.

Lee WJ, Ser KH, Lee YC, Tsou JJ, Chen SC, Chen JC. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y vs. mini-gastric bypass for the treatment of morbid obesity: a 10-year experience. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1827–34.

Chevallier JM, Chakhtoura G, Zinzindohoué F. Laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass. J Chir. 2009;146:60–4.

•• Chevallier JM, Arman G, Guenzi M, Rau C, Bruzzi M, Beaupel N, et al. One thousand single anastomosis (Omega Loop) gastric bypasses to treat morbid obesity in a 7-year period: outcomes show few complications and good efficacy. Obes Surg. 2015;25:951–8. Results of 1000 OAGB of our team.

Bruzzi M, Rau C, Voron T, Guenzi M, Berger A, Chevallier JM. Single anastomosis or mini-gastric bypass: long-term results and quality of life after a 5-year follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:321–6.

• Musella M, Susa A, Greco F, De Luca M, Manno E, Di Stefano C, et al. The laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass: the Italian experience: outcomes from 974 consecutive cases in a multicenter review. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:156–63. Results of 1000 OAGB of a reference team.

•• Musella M, Apers J, Rheinwalt K, Ribeiro R, Manno E, Greco F, et al. Efficacy of bariatric surgery in type 2 diabetes mellitus remission: the role of mini gastric bypass/one anastomosis gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy at 1 year of follow-up. A European survey. Obes Surg. 2016;26:933–40. Multicentric European results of OAGB in the treatment of diabetes.

Carbajo M, García-Caballero M, Toledano M, Osorio D, García-Lanza C, Carmona JA. One-anastomosis gastric bypass by laparoscopy: results of the first 209 patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:398–404.

•• Zubiaga L, Abad R, Ruiz-Tovar J, Enriquez P, Vílchez JA, Calzada M, et al. The effects of one-anastomosis gastric bypass on glucose metabolism in Goto-Kakizaki rats. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2622–8. Research concerning the effects of OAGB on glycemic control in rats.

Bruzzi M, Duboc H, Gronnier C, Rainteau D, Couvelard A, Le Gall M, et al. Long-term evaluation of biliary reflux after experimental one-anastomosis gastric bypass in rats. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1119–22.

Deitel M. 2015Letter to the Editor: bariatric surgery worldwide reveals a rise in mini-gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2013;25:2166–8.

Georgiadou D, Sergentanis TN, Nixon A, Diamantis T, Tsigris C, Psaltopoulou T. Efficacy and safety of laparoscopic mini gastric bypass. A systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:984–91.

Mahawar KK, Jennings N, Brown J, Gupta A, Balupuri S, Small PK. “Mini” gastric bypass: systematic review of a controversial procedure. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1890–8.

Mahawar KK, Carr WRJ, Balupuri S, Small PK. 2013Controversy surrounding “mini” gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2014;24:324–33.

• Mahawar KK, Kumar P, Carr WR, Jennings N, Schroeder N, Balupuri S, et al. Current status of mini-gastric bypass. J Minim Access Surg. 2016;12:305–10. Review of the OAGB results.

Victorzon M. Single-anastomosis gastric bypass: better, faster, and safer? Scand J Surg. 2015;104:48–53.

Chakhtoura G, Zinzindohoué F, Ghanem Y, Ruseykin I, Dutranoy JC, Chevallier JM. Primary results of laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass in a French obesity-surgery specialized university hospital. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1130–3.

Bruzzi M, Voron T, Zinzindohoue F, Berger A, Douard R, Chevallier JM. Revisional single-anastomosis gastric bypass for a failed restrictive procedure: 5-year results. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:240–5.

•• Carbajo MA, Luque-de-Leon E, Jimenez JM, Ortiz-de-Solorzano J, Perez-Miranda M, Castro-Alija MJ. Laparoscopic one-anastomosis gastric bypass: technique, results, and long-term follow-up in 1200 patients. Obes. Surg. 2017;27:1153–67. Results of 1200 AOGB patients with a follow-up exceeding 10 years (for some patients).

Noun R, Riachi E, Zeidan S, Abboud B, Chalhoub V, Yazigi A. Mini-gastric bypass by mini-laparotomy: a cost-effective alternative in the laparoscopic era. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1482–6.

Noun R, Skaff J, Riachi E, Daher R, Antoun NA, Nasr M. One thousand consecutive mini-gastric bypass: short- and long-term outcome. Obes Surg. 2012;22:697–703.

Kular KS, Manchanda N, Rutledge R. A 6-year experience with 1,054 mini-gastric bypasses—first study from Indian subcontinent. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1430–5.

Lee WJ, Wang W, Lee YC, Huang MT, Ser KH, Chen JC. Laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass: experience with tailored bypass limb according to body weight. Obes Surg. 2008;18:294–9.

Lee WJ, Wang W, Lee YC, Huang MT, Ser KH, Chen JC. Effect of laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass for type 2 diabetes mellitus: comparison of BMI>35 and <35 kg/m2. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:945–52.

Wang W, Wei PL, Lee YC, Huang MT, Chiu CC, Lee WJ. Short-term results of laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2005;15:648–54.

Guenzi M, Arman G, Cordun C, Moszkowicz D, Voron T, Chevallier JM. Remission of type 2 diabetes after omega loop gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2669–74.

•• Quan Y, Huang A, Ye M, Xu M, Zhuang B, Zhang P, et al. Efficacy of laparoscopic mini gastric bypass for obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:152852. Meta-analysis of OAGB and type-2 diabetes.

• Taha O, Abdelaal M, Abozeid M, Askalany A, Alaa M. Outcomes of omega loop gastric bypass, 6-years experience of 1520 cases. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1952–1960. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2623-8. Results of 1520 AOGB patients published in 2017.

• Lee WJ, Chong K, Lin Y, Wei J, Chen S. Laparoscopic sleeve Gastrectomy versus single anastomosis (mini- ) gastric bypass for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus : 5-year results of a randomized trial and study of incretin effect. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1552–62. A randomized trial comparing OAGB and sleeve.

Kular KS, Manchanda N, Rutledge R. Analysis of the five-year outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy and mini-gastric bypass: a report from the Indian sub-continent. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1724–8.

Celik A, Pouwels S, Karaca FC, Cagiltay E, Ugale S, Etikan I, et al. Time to glycemic control—an observational study of 3 different operations. Obes Surg. 2017;27:694–702.

Garcia-Caballero M, Valle M, Martinez-Moreno JM, Miralles F, Toval JA, Mata JM, et al. Resolution of diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome in normal weight 24-29 BMI patients with one anastomosis gastric bypass. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27:623–31.

Kular KS, Manchanda N, Cheema GK. Seven years of mini-gastric bypass in type II diabetes patients with a body mass index <35 kg/m2. Obes Surg. 2016;26:1457–62.

Bruzzi M, Chevallier JM, Czernichow S. One-anastomosis gastric bypass: why biliary reflux remains controversial? Obes Surg. 2017;27:545–7.

DeMaria EJ, Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, Meador JG, Wolfe LG. Results of 281 consecutive total laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypasses to treat morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2002;235:640–5.

Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, Ramanathan R, Luketich J. Outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2000;232:515–29.

Wittgrove AC, Clark GW, Tremblay LJ. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y: preliminary report of five cases. Obes Surg. 1994;4:353–7.

Wittgrove AC, Clark GW. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y- 500 patients: technique and results, with 3-60 month follow-up. Obes Surg. 2000;10:233–9.

Rubino F, Kaplan LM, Schauer PR, Cummings DE. The diabetes surgery summit consensus conference: recommendations for the evaluation and use of gastrointestinal surgery to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 2010;251:399–405.

• Cummings DE, Arterburn DE, Westbrook EO, Kuzma JN, Stewart SD, Chan CP, et al. Gastric bypass surgery vs intensive lifestyle and medical intervention for type 2 diabetes: the CROSSROADS randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2016;59:945–53. Randomized controlled trial.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Reem Abou Ghazaleh, Matthieu Bruzzi, Karen Bertrand, Leila M’harzi, Franck Zinzindohoue, Richard Douard, Anne Berger, Sébastien Czernichow, Claire Carette, and Jean-Marc Chevallier declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Lipid and Metabolic Effects of Gastrointestinal Surgery

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abou Ghazaleh, R., Bruzzi, M., Bertrand, K. et al. Is Mini-Gastric Bypass a Rational Approach for Type-2 Diabetes?. Curr Atheroscler Rep 19, 51 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-017-0689-3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-017-0689-3