Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of the current study was to review the available literature on morbidly obese patients treated with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) in order to assess the clinical outcomes of the routine closure of the mesenteric defects.

Methods

A literature search was performed in PubMed, Cochrane library, and Scopus, in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.

Results

Nine studies met the inclusion criteria. A total of 16,520 patients were incorporated with a mean follow-up ranging from 34 to 120 months. The closure of the mesenteric defects was associated with a lower incidence of internal hernias (odds ratio, 0.25 [95% confidence interval 0.20, 0.31]; p < 0.01), small bowel obstruction (SBO) (0.30 [0.17, 0.52]; p < 0.0001) and reoperations (0.28 [0.15, 0.52]; p < 0.001). Both approaches presented similar complication rates and % excess weight loss (%EWL).

Conclusion

The present meta-analysis is the best currently available evidence on the topic and supports the routine closure of the mesenteric defects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Morbid obesity is a global epidemic, and bariatric surgery remains the main therapeutic option providing significant and sustainable weight loss [1], along with diabetes remission and enhancement of the patients’ metabolic profile [2]. Currently, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) is the main operation of choice in many bariatric centers [3] regarding patients with morbid obesity and metabolic disorders or as salvage operation after a failed bariatric procedure [4].

Over the past years, the increased incidence of post-LRYGB small bowel obstruction (SBO) due to internal hernia (IH) after LRYGB has become a major concern. According to recent data, the incidence of post-LRYGB SBO has been estimated at 10–16%, with the IH being the main cause [5, 6]. Nonetheless, the evidence provided by consecutive series of patients undergoing LRYGB suggests that the routine closure of mesenteric defects, both at the Petersen and jejunal sites, might reduce the rate of postoperative IH [7].

Meanwhile, there is a concern that the closure itself might increase the risk for perioperative complications, including the impaired alimentary limb emptying (kinking of the jejunojejunostomy). Despite the absence of conclusive data regarding the effect of routine mesenteric defect closure on the reduction of the incidence of SBO or the extent of the morbidity caused by the closure of the mesenteric defects, the routine closure has been widely adopted [8, 9], even when an antecolic, antegastric LRGYB is performed.

As the number of studies assessing the feasibility of routine mesenteric defects closure during LRYGB increases and new randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been published, it is necessary to reassess whether the perioperative outcomes of closure and non-closure are at least equivalent. The purpose of this study was to summarize the currently available evidence evaluating the routine closure of mesenteric defects during LRYGB, thus providing the best currently available level of evidence.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Articles Selection

The present study was conducted under the protocol agreed by all authors and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [10]. A thorough literature search was performed in PubMed (Medline), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Studies (CENTRAL), and Scopus (Elsevier) databases (last search, August 30, 2019) using the following terms in every possible combination: “roux-en-y gastric bypass,” “rygb,” “internal hernia,” “hernia,” “small bowel obstruction,” “bowel obstruction,” “mesenteric defects,” “mesenteric defects closure,” “petersen defects,” “jejunostomy,” and “obesity.” Inclusion criteria were (1) original comparative reports with ≥ 10 patients, (2) written in the English language, (3) published from 1990 to 2019, (4) conducted on human subjects, and (5) reporting comparative outcomes of closure and non-closure of mesenteric defects during LRYGB on patients with morbid obesity. Two independent reviewers (DEM and VST) extracted the data from the included studies. Any discrepancies between the investigators regarding the inclusion or exclusion of studies were discussed with the senior author (DZ) to include articles that best matched the criteria until consensus was reached. Furthermore, the reference lists of all included articles were assessed for any additional eligible studies. Besides, the kappa coefficient test was applied to assess the level of agreement between the reviewers.

Data Extraction

For each eligible study, data was extracted relative to demographics (gastric bypass approach, study sample, female ratio, mean age, preoperative body mass index (BMI), follow-up), along with the intraoperative parameters and postoperative outcomes (mean operative time (MOT), length of hospital stay (LOS), the incidence of postoperative internal hernia, along with the time interval to internal hernia presentation, the incidence of leaks, bleeding, and ulcer). Two authors (DEM and VST) performed the data extraction independently and compared the validity of their data. Any discrepancies were discussed with the senior author (DZ) until consensus was reached.

Statistical Analysis

Regarding the categorical outcomes, the odds ratio (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated, based on the extracted data, employing the random-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel statistical method). OR < 1 denoted outcome was more frequent in the non-closure group. Continuous outcomes were evaluated utilizing the weighted mean difference (WMD) with its 95% CI, using random-effects (inverse variance statistical method) models, to calculate pooled effect estimates. In cases where WMD < 0, the values in the non-closure group were higher. We selected the random-effects model since we did not expect that all the included studies would share a common effect size. The between-study heterogeneity was assessed through the Cochran Q statistic and by estimating I2 [11].

In cases that multiple studies incorporated the same population, only the largest study or the one with the longest follow-up was included in the present meta-analysis.

Quality and Publication Bias Assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) [12] was used as an assessment tool to evaluate the non-RCTs. The scale’s range varies from zero to nine stars, and studies with a score equal to or higher than five were considered to have an adequate methodological quality to be included. The RCTs were assessed for their methodological quality with the tools that are used to evaluate the risk of bias according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [11]. Two reviewers (DEM, VST) rated the studies independently and the final decision was reached by consensus.

Our initial aim was to assess the existence of publication bias using the Egger’s formal statistical test [13]. However, the statistical evaluation could not be performed because the number of studies included in the analysis was not adequate (less than 10), thus compromising substantially the power of the test.

Results

Article Selection and Patient Baseline Characteristics

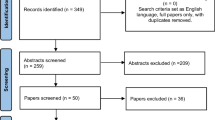

The flow diagram of the search of the literature is shown in Fig. 1. Among the 183 articles in PubMed, CENTRAL, and Scopus that were retrieved, nine comparative studies were included in the qualitative and quantitative analysis [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The level of agreement between the two reviewers regarding the inclusion of the studies was “good” (kappa = 0.768; 95% CI 0.572, 0.964). The study design was retrospective in six studies [15,16,17,18,19,20], prospective in one study [14], and RCT in two studies [21, 22]. The included studies were conducted in Norway [14], France [15], Belgium [16], India [17], USA [18, 21], Colombia [19], Mexico [20], and Sweden [22], and they were published between 2010 and 2019. The total study population was 16,520 patients, with a mean follow-up ranging from 34 to 120 months. All patients underwent laparoscopic antecolic, antegastric LRYGB. No comparative studies with retrocolic LRYGB were identified. The closure of the mesenteric defects was performed using a stapler in one study [14], non-absorbable continuous sutures in other studies [15,16,17,18,19,20, 22] and non-absorbable interrupted sutures in one study [21]. The baseline characteristics, along with the Newcastle-Ottawa rating scale (NOS) assessment of the included studies are demonstrated in Table 1. Both groups were similar regarding age and female ratio. However, the non-closure group was associated with a higher baseline BMI (Table 2). Moreover, the quality assessment of RCTs is presented in Table S1. Pooled ORs, WMDs, I2, and p values regarding the baseline characteristics, along with the primary and secondary endpoints are summarized in Table 2.

Primary Endpoints—Efficacy Endpoints

According to our analysis, the incidence of IH was significantly greater in the non-closure group (OR 0.25 [95% CI: 0.20, 0.31]; p < 0.01) (Fig. 2). In the subgroup analysis, an increased incidence of IH was reported at both the Petersen (OR 0.26 [95% CI 0.18, 0.37]; p < 0.01), ranging from 0 to 5%, and the jejunal site (OR 0.25 [95% CI 0.18, 0.35]; p < 0.01), ranging from 0 to 4.8%, regarding the non-closure group. These outcomes were further certified by sensitivity analysis. In fact, we re-assessed the incidence of IH by including only the RCTs and found a higher IH rate in patients allocated at the non-closure group (Fig. S1). The time interval to IH presentation was greater to the non-closure group (WMD − 10.73 [− 12.85, − 8.60]; p < 0.01) (Fig. S1).

Primary Endpoints—Safety Endpoints

Both groups were associated with similar outcomes regarding the incidence of bleeding (OR 0.82 [95% CI 0.54, 1.26]; p = 0.37), leakage (OR 1.15 [0.68, 1.95]; p = 0.59), and marginal ulcer (1.69 [0.46, 6.24]; p = 0.43) (Fig. S1). Nonetheless, the non-closure group presented a higher incidence of late SBO (OR 0.27 [95% CI 0.17, 0.43]; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3a), which is mainly attributed to internal hernia, or in more rare cases to adhesions. This finding is in accordance with the higher incidence of IH in the non-closure group. In contrast, the incidence of early SBO, mainly attributed to kinking of the jejunostomy due to the stiffening of the anastomosis by the mesenteric closure, was higher in the closure group (OR 2.83 [95% CI 1.29, 6.22]; p = 0.010), but the number of cases was limited. In fact, only two studies [14, 22] reported cases of SBO due to the kinking of the jejunostomy. According to the first study [14], there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the kinking of the jejunojejunostomy. On the other hand, the second study [22] reported a significantly higher incidence of kinking in the closure group. Due to the limited provided data, no further analysis could be performed regarding the kinking of the jejunojejunostomy. In addition, the risk of reoperation due to SBO was significantly greater in the non-closure group (0.28 [0.15, 0.52]; p < 0.001) (Fig. 3b). The mortality rate was zero in the non-closure group. Only one case of postoperative death has been reported in the closure group, attributed to port-site hernia with incarcerated bowel.

Secondary Endpoint—Weight Loss

In the present meta-analysis, we evaluated the % excess weight loss (%EWL) reported in both groups since it has been identified as a risk factor for reoperation because of SBO caused by IH [22]. No significant difference was reported between the two groups regarding the % excess weight loss (%EWL) (WMD 2.74 [95% CI − 5.51, 10.99]; p = 0.52), as shown in Fig. S1.

Publication Bias

Heterogeneity was high regarding the baseline BMI and age, along with the incidence of SBO. On the other hand, heterogeneity was low regarding all the primary and secondary endpoints. The Egger’s test could not be performed due to the inadequate number of the included studies. The funnel plots that were produced to assess the publication bias are shown in Fig. S2. The funnel plot regarding the incidence of IH was symmetrical. The asymmetries that were found in the funnel plots regarding the other endpoints are mainly attributed to the small number of the included studies and the possible bias regarding the selection of the patients, thus proposing that additional studies are necessary in order to reduce the potential publication bias.

Discussion

LRYGB is one of the most popular bariatric procedures worldwide and the most frequently performed operation in west Europe and North America mainly due to its advantages in the early and late postoperative courses [23]. Despite the fact that initially, the description of LRYGB did not include the closure of the mesenteric defects, recent evidence has triggered an extensive debate regarding the establishment of the mesenteric closure as the standard of care in LRYGB [24]. The defects of interest include the mesenteric defects at the jejunojejunostomy, subsequent to the creation of the roux limb, along with the space posterior to the roux limb and distal to the mesocolon referred as Petersen defect. In fact, SBO caused by IH following LRYGB remains a significant risk that is associated with postoperative morbidity and mortality [25]. However, there is only limited high-quality evidence available provided by only two RCTs [21, 22] so as to reach a consensus regarding the best practice. To our best knowledge, the present study is the first meta-analysis, assessing the potential superiority of closure of mesenteric defects compared with non-closure that incorporates evidence provided by RCTs, thus providing the best level of evidence currently available. A previous meta-analysis [9] that incorporated studies published until 2013 failed to include any RCTs, thus limiting the level of evidence, while the analyses evaluating the incidence of IH were associated with high heterogeneity.

According to our outcomes, the closure of the mesenteric defects with running, non-absorbable sutures during LRYGB significantly reduces the incidence of IH. Given the increase of internal hernia incidence over time, the non-absorbable materials are considered to be superior compared to absorbable. Nonetheless, the use of sutures compared with other techniques such as glue or clips remains debatable. Clips and interrupted sutures were used for mesenteric closure in each study [14, 21], with similar outcomes. Sutures provide higher tensile strength [26], but clips were also associated with increased efficiency [7]. The most efficient technique for closure of mesenteric defects should be assessed in future comparative studies.

Our outcomes also demonstrate that the routine closure of mesenteric defects is associated with similar rates of postoperative complications. Closure of the mesenteric defects has been associated with an increased rate of kinking of the jejunojejunostomy. A potential pathophysiological mechanism explaining this phenomenon is the increased rigidity and stiffening of the jejunojejunostomy as a consequence of the antecolic location of the anastomosis, along with the closure of the mesenteric defects [27]. In the present meta-analysis, only two studies [14, 22] reported contradicted outcomes regarding the kinking of the jejunostomy. In fact, different techniques have been proposed in order to reduce the incidence of kinking of the jejunojejunostomy, such as setting an anti-obstructive stitch [28], and the wide division of the mesentery, along with the double stapling of the jejunojejunostomy. Nonetheless, the currently available evidence to support these preventive measures is weak and new studies are needed to further assess this issue.

In many studies, the efficacy of the closure of mesenteric defects was assessed in terms of IH rate. Nonetheless, the presence of IH is in many cases challenging to be defined [29]. In the same context, SBO attributed to other causes might be underestimated, thus posing a significant bias regarding the evaluation of the efficacy of the mesenteric defect closure. Nonetheless, in the present meta-analysis, the rate of reoperations due to SBO was also assessed. According to our outcomes, the non-closure group presented a significantly higher risk of reoperations.

The current meta-analysis demonstrates that the routine closure of the mesenteric defects during LRYGB is effective, safe, and is associated with a significantly lower incidence of IH, late SBO, and reoperations. Nonetheless, a higher incidence of early IH caused by kinking of the jejunojejunostomy is reported in the closure group. The present meta-analysis also highlights the need for additional studies assessing the closure of mesenteric defects. Ideally, these would be randomized controlled studies, with prospective design and longer follow-up in order to compare the different techniques and materials proposed for mesenteric closure, along with the techniques suggested in order to reduce the incidence of kinking of the jejunojejunostomy.

The limitations of this meta-analysis reflect the limitations of the studies included. One study [14] was prospective and six [15,16,17,18,19,20] retrospective, thus posing a certain limitation in the present study. Two studies [21, 22] were RCTs. Moreover, the heterogeneity was high regarding the baseline BMI and age, along with the incidence of SBO. Furthermore, the non-closure group was associated with a higher baseline BMI. Finally, the differences among institutions regarding the data definitions and the lack of standardization of the surgical techniques pose another limitation.

On the other hand, the strengths of the current meta-analysis include (1) the clear protocol, (2) the well-defined inclusion-exclusion criteria, (3) the literature search in three different databases, (4) the quality assessment of the included studies, and (5) the up-to-date demonstration of the outcomes of data extraction and analysis.

Conclusion

The present meta-analysis identified and included 9 studies assessing the routine closure of the mesenteric defects during LRYGB. These studies suggest that the mesenteric closure is associated with a lower incidence of IH, late SBO, and reoperations, along with a similar level of feasibility and safety. The present meta-analysis provides the best currently available level of evidence on the topic and supports the routine closure of the mesenteric defects. Nonetheless, surgeons should be aware of the potential risk of early postoperative SBO due to kinking of the jejunojejunostomy. Future studies with longer follow-up are necessary to further assess the different techniques/materials suggested for closure, along with the proposed measures for the prevention of kinking of the jejunostomy.

References

Colquit JL, Picot J, Loveman E, et al. Surgery for obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD003641.

Magouliotis DE, Tasiopoulou VS, Sioka E, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on metabolic and gut microbiota profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2595-8.

Saber AA, Elgamal MH, McLeod MK. Bariatric surgery: the past, present, and future. Obes Surg. 2008;18:121–8.

Magouliotis DE, Tasiopoulou VS, Svokos AA, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy as revisional procedure after adjustable gastric band: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2644-3.

Abasbassi M, Pottel H, Deylgat B, et al. Small bowel obstruction after antecolic antegastric laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass without division of small bowel mesentery: a single-centre, 7-year review. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1822–7.

Higa K, Ho T, Tercero F, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:516–25.

Aghajani E, Jacobsen HJ, Nergaard BJ, et al. Internal hernia after gastric bypass: a new and simplified technique for laparoscopic primary closure of the mesenteric defects. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:641–5.

Martin MJ. Comment on: Impact of complete mesenteric closure on small bowel obstruction and internal mesenteric hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:854–5.

Geubbels N, Lijftogt N, Fiocco M, et al. Meta-analysis of internal herniation after gastric bypass surgery. Br J Surg. 2015;102:451–60.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100.

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration 2011 Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Aghajani E, Nergaard BJ, Leifson BG, et al. The mesenteric defects in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 5 years follow-up of non-closure versus closure using the stapler technique. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(9):3743–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5415-2.

Amor IB, Kassir R, Debs T, et al. Impact of mesenteric defect closure during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB): a retrospective study for a total of 2093 LRYGB. Obes Surg. 2019;29:3342–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04000-5.

Blockhuys M, Gypen B, Heyman S, et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic gastric bypass: effect of closure of the Petersen defect - single-center study. Obes Surg. 2019;29(1):70–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3472-9.

Chowbey P, Baijal M, Kantharia NS, et al. Mesenteric defect closure decreases the incidence of internal hernias following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a retrospective cohort study. Obes Surg. 2016;26(9):2029–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2049-8.

de la Cruz-Muñoz N, Cabrera JC, Cuesta M, et al. Closure of mesenteric defect can lead to decrease in internal hernias after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(2):176–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2010.10.003.

Lopera CA, Vergnaud JP, Cabrera LF, et al. Preventative laparoscopic repair of Petersen’s space following gastric bypass surgery reduces the incidence of Petersen’s hernia: a comparative study. Hernia. 2018;22(6):1077–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1814-0.

Rodríguez A, Mosti M, Sierra M, et al. Small bowel obstruction after antecolic and antegastric laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: could the incidence be reduced? Obes Surg. 2010;20(10):1380–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0164-5.

Rosas U, Ahmed S, Leva N, et al. Mesenteric defect closure in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(9):2486–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3970-3.

Stenberg E, Szabo E, Ågren G, et al. Closure of mesenteric defects in laparoscopic gastric bypass: a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open-label trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1397–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01126-5.

Welbourn R, Hollyman M, Kinsman R, et al. Bariatric surgery worldwide: baseline demographic description and one-year outcomes from the Fourth IFSO Global Registry Report 2018. Obes Surg. 2019;29:782–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3593-1.

Garza Jr E, Kuhn J, Arnold D, et al. Internal hernias after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Am J Surg. 2004;188:796–800.

Higa KD, Ho T, Boone KB. Internal hernias after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: incidence, treatment and prevention. Obes Surg. 2003;13:350–4.

Jacobsen H, Dalenback J, Ekelund M, et al. Tensile strength after closure of mesenteric gaps in laparoscopic gastric bypass: three techniques tested in a porcine model. Obes Surg. 2013;23:320–4.

Al Harakeh AB, Kallies KJ, Borgert AJ, et al. Bowel obstruction rates in antecolic/antegastric versus retrocolic/retrogastric Roux limb gastric bypass: a meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(1):194–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2015.02.004.

Brolin RE. The antiobstruction stitch in stapled Roux-en-Y enteroenterostomy. Am J Surg. 1995;169:355–7.

Ekelund M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of internal herniation after gastric bypass surgery. Br J Surg. 2015;102:460–1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Does not apply.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Magouliotis, D.E., Tzovaras, G., Tasiopoulou, V.S. et al. Closure of Mesenteric Defects in Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass: a Meta-Analysis. OBES SURG 30, 1935–1943 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04418-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04418-2