Abstract

Introduction

Internal herniation is a potential complication following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB). Previous studies have shown that closure of mesenteric defects after LRYGB may reduce the incidence of internal herniation. However, controversy remains as to whether mesenteric defect closure is necessary to decrease the incidence of internal hernias after LRYGB. This study aims to determine if jejeunal mesenteric defect closure reduces incidence of internal hernias and other complications in patients undergoing LRYGB.

Methods

105 patients undergoing laparoscopic antecolic RYGB were randomized into two groups: closed mesenteric defect (n = 50) or open mesenteric defect (n = 55). Complication rates were obtained from the medical record. Patients were followed up to 3 years post-operatively. Patients also completed the gastrointestinal quality of life index (GI QoL) pre-operatively and 12 months post-operatively. Outcome measures included: incidence of internal hernias, complications, readmissions, reoperations, GI QoL scores, and percent excess weight loss (%EWL).

Results

Pre-operatively, there were no significant differences between the two groups. The closed group had a longer operative time (closed-153 min, open-138 min, p = 0.073). There was one internal hernia in the open group. There was no significant difference at 12 months for decrease in BMI (closed-15.9, open-16.3 kg/m2, p = 0.288) or %EWL (closed-75.3 %, open-69.0 %, p = 0.134). There was no significant difference between the groups in incidence of internal hernias and general complications post-operatively. Both groups showed significantly improved GI QoL index scores from baseline to 12 months post-surgery, but there were no significant differences at 12 months between groups in total GI QoL (closed-108, open-112, p = 0.440).

Conclusions

In this study, closure or non-closure of the jejeunal mesenteric defect following LRYGB appears to result in equivalent internal hernia and complication rates. High index of suspicion should be maintained whenever internal hernia is expected after LRYGB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

As rates of morbid obesity in the United States have increased over the past few decades, so has the utilization of bariatric surgery to combat this growing epidemic. From 1998 to 2008, data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) revealed that the number of bariatric surgery procedures performed during that time increased nearly tenfold [1, 2]. This is due, in large part, to the enduring efficacy of surgical weight loss [3, 4], and the increased safety of these procedures. The 30-day mortality rate following bariatric surgery ranges from 0.1 to 0.3 % [1, 5, 6].

Gastric bypass is the most common bariatric procedure used for surgical weight loss. Estimates from the bariatric outcomes longitudinal database revealed that 55 % of bariatric procedures performed in 2009 were some form of gastric bypass [6]. Gastric bypass provides the greatest amount of weight loss [7–9] compared to sleeve gastrectomy, adjustable gastric band, and lifestyle changes.

The laparoscopic approach to the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) is now widespread and much more commonly used than the open approach [10]. While the laparoscopic approach provides many advantages over the open approach, the incidence of internal hernias after gastric bypass has been shown to be higher in patients whose gastric bypass is done laparoscopically [11]. This is thought to be due to the decreased formation of post-operative adhesions after laparoscopy [12]. The formation of internal hernias in patients who undergo LRYGB is one of the most serious complications that can occur following this procedure.

The incidence of internal hernia formation following LRYGB can range from 1.1–9 % [11–15], with a mean of 2.51 % [13]. The rate of internal herniation is higher in patients who undergo laparoscopic RYGB versus open RYGB (0.8–5 %) [11–13, 15, 16], and is primarily the result of the creation of potential internal spaces due to the Roux-en-Y anatomy [12] through which the small bowel can herniate. In the antecolic approach, it is most commonly in the transverse mesocolon and Roux-limb mesentery (Petersen’s defect), or mesenteric defect at the jejuno-jejunostomy [12]. Internal hernia after LRYGB is a medical emergency that can lead to small bowel obstruction, small bowel ischemia, and even death [17].

Prevention of internal hernias is often done through closure of the mesenteric defects created during LRYGB [11, 12, 18, 19]. While many studies have shown that closure of mesenteric defects after LRYGB surgery can significantly decrease the risk of internal herniation, very few randomized controlled trials have been done to demonstrate that closure of the mesenteric defect indeed reduces the incidence of internal hernias following LRYGB [13, 18]. The purpose of this study is to determine if jejuno-jejeunal mesenteric defect closure reduces incidence of hernias and complications in patients undergoing LRYGB.

Methods

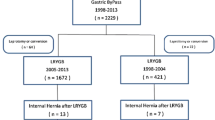

105 patients undergoing laparoscopic antecolic RYGB [20] were randomized into two groups: closed mesenteric defect (n = 50) and open mesenteric defect (n = 55). LRYGB procedures were performed using a standard RYGB 15–30 cm3 pouch and a 125 cm Roux Limb. The omentum was divided up to transverse colon to allow an antecolic orientation of the Roux limb. The jejunum was divided 40 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz and a jejuno-jejunostomy was performed with proximal and distal firings of the Endo-GIA 45 mm white load stapler. The Roux limb was mobilized from the mesentery and placed in an antecolic position. Gastric pouch was completed with multiple linear blue load firings to the Angle of His in a vertical fashion, and the Roux limb was intubated with a 25 mm EEA stapler, docked with the anvil, and fired to create the gastro-jejunostomy.

In all patients, potential defects between the transverse mesocolon and Roux-limb mesentery (Petersen’s defect) were closed using a 2-0 braided polyester suture in interrupted fashion. For patients in the closed group, the additional defect at the jejuno-jejunostomy was closed using the same technique.

Outcome measures at 1 year included incidence of internal hernia, other complications, readmissions, reoperations, gastrointestinal quality of life index scores (GI QoL), and percent excess weight loss (%EWL). Any patient complaining of upper abdominal pain suggesting acute intestinal obstruction was evaluated for presence of internal hernia. CT scan with intravenous and oral contrast was done and laparoscopic exploration was done as indicated.

Complication rates were obtained from the medical record. Complications recorded include anastomotic leak, GI bleed, abdominal abscess, small bowel obstruction, DVT/PE, wound infection, vitamin deficiency/dehydration, ulcer, and strictures. Readmissions and reoperations were also obtained from medical records. Patients were contacted up to 3 years post-operatively to obtain incidences of complications that may not have been captured from institutional records. Patients also completed the GI QoL pre-operatively and 12 months post-operatively in order to determine symptoms associated with obstruction.

IRB approval was obtained for this study (Stanford IRB#18347). Informed consent was obtained from patients as they were recruited from clinic. Randomization was performed by random number table on day of surgery. Inclusion criterion was primary laparoscopic gastric bypass and exclusion criterion was revisional bariatric surgery. A power analysis was performed with a proposed paired, 2 sided T test analysis, 0.05 α level, 0.8 desired power, a 6 % incidence rate with non-closure, 0 % incidence rate for closure, 12 % sigma standard deviation rate and the resultant sample size was 32 per cohort.

Dichotomous variables were analyzed using χ 2 test, and continuous using two-tailed t test. Analysis was performed using STATA software, release 12, and GraphPad Prism 6.

Results

Pre-operatively, there were no significant demographic differences between the two groups. Both closed and open groups had pre-operative (pre-op) demographics similar to other bariatric populations, with a pre-op BMI greater than 40 kg/m2, and the majority of patients as female, white, and having private insurance. Both groups had similar rates of prior abdominal surgeries, and there were no significant differences in pre-op comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes mellitus (type 2), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and metabolic syndrome. The closed group had longer operative times compared to the open group (closed-153 min, open-138 min, p = 0.073). However, this difference was not significant. Pre-operative demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Between the two groups, there was no significant difference at 12 months for decrease in BMI (closed-15.9, open-16.3 kg/m2, p = 0.288), change in waist circumference (closed-24.1 cm, open-30.0 cm, p = 0.359), or the %EWL (closed-75.2 %, open-69.1 %, p = 0.179).

Average follow-up for incidence of internal hernias and other complications for both groups was 34 months post-operative (post-op) at time of analysis. Clinical follow-up at 12 months was 75 %; however, all (100 %) patients were contacted approximately 36 months post-op to determine incidence of internal hernias and other complications.

There was no significant difference between the groups in incidence of internal hernias. In the open group, 1 internal hernia was noted 14 months post-op (Incidence rate 1.9 %). Laparotomy at an external institution revealed site of hernia to be at the jejuno-jejunal anastomosis. Additionally, there were no significant differences in incidence of major or minor 30-day post-operative complications. Also, there were no differences in incidence of strictures or ulcers beyond the initial 30-day post-operative period. Both closed and open groups had 2 patients with 30-day readmissions after LRYGB (p = 0.904), and there were no significant differences in 30-day reoperations between the two groups (p = 0.253). Results are summarized in Table 2.

Both groups showed improvement in GI QoL index scores from baseline to 12 months post-op (closed-25 %, Open-21.6 % improvement, p = 0.672), but there were no significant differences at 12 months between groups in total GI QoL (closed-108, open-112, p = 0.440), physical domain score (closed-17.9, open-17.7, p = 0.909), and symptoms domain score (closed-60.2, open-60.0, p = 0.919). However, closed group had a lower emotional domain score at 12 months post-operation compared to open group (closed-14.5, open-16.7, p = 0.042). All other domains showed no significant differences. Results are summarized in Table 3. For the purposes of this analysis 3 patients (2 from closed group, 1 from open group) were excluded due to the fact that LRYGB being preformed was a revisional procedure at the time of this study.

Discussion

In this study, closure or non-closure of the jejeunal mesenteric defect following LRYGB appears to result in equivalent internal hernia and complication rates, and is consistent with published literature.

The mean time from surgery to internal hernia has been reported to be approximately 9–28 months [11, 13–15]. While follow-up for our study was approximately 34 months on average, longer follow-up may be needed to capture all incidence of internal hernia. Internal herniation in patients who have undergone LRYGB has been noted to occur up to 6 years after surgery.

Although this study did not show a statistically significant difference in the rate of internal hernias following LYRGB between patients with closed defects versus those with open, a high clinical index of suspicion for internal herniation should always be maintained in any LRYGB patient who presents abdominal pain and/or clinical signs and symptoms of small bowel obstruction. A laparoscopic approach can be undertaken to reduce the hernia contents and close all defects [14, 21, 22].

While this study was a randomized controlled trial, larger, multi-center randomized controlled trials may be needed to provide a definite recommendation. Our sample size was 105, and larger trials may provide more statistical power to determine whether closure of mesenteric defect leads to lower rates of internal hernias in LRYGB patients. Our practice is to close all potential defects in LRYGB patients.

References

Wolfe BM, Morton JM (2005) Weighing in on bariatric surgery: procedure use, readmission rates, and mortality. JAMA 294:1960–1963. doi:10.1001/jama.294.15.1960

Nguyen NT, Masoomi H, Magno CP, Nguyen X-MT, Laugenour K, Lane J (2011) Trends in use of bariatric surgery, 2003–2008. J Am Coll Surg 213:261–266. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.04.030

Himpens J, Verbrugghe A, Cadière G-B, Everaerts W, Greve J-W (2012) Long-term results of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: evaluation after 9 years. Obes Surg 22:1586–1593. doi:10.1007/s11695-012-0707-z

Schouten R, Wiryasaputra DC, Dielen FMH, Gemert WG, Greve JWM (2010) Long-term results of bariatric restrictive procedures: a prospective study. Obes Surg 20:1617–1626. doi:10.1007/s11695-010-0211-2

Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC, Wahed AS, Berk P, Chapman W, Pories W, Courcoulas A, McCloskey C, Mitchell J, Patterson E, Pomp A, Staten MA, Yanovski SZ, Thirlby R, Wolfe B (2009) Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 361:445–454. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0901836

DeMaria EJ, Pate V, Warthen M, Winegar DA (2010) Baseline data from American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery-designated Bariatric Surgery Centers of Excellence using the Bariatric Outcomes Longitudinal Database. Surg Obes Relat Dis 6:347–355. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2009.11.015

Goodpaster BH, Delany JP, Otto AD, Kuller L, Vockley J, South-Paul JE, Thomas SB, Brown J, McTigue K, Hames KC, Lang W, Jakicic JM (2010) Effects of diet and physical activity interventions on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in severely obese adults: a randomized trial. JAMA 304:1795–1802. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1505

Cunneen SA, Phillips E, Fielding G, Banel D, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Sledge I (2008) Studies of Swedish adjustable gastric band and lap-band: systematic review and meta-analysis. SOARD 4:174–185. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2007.10.016

Hutter MM, Schirmer BD, Jones DB, Ko CY, Cohen ME, Merkow RP, Nguyen NT (2011) First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Ann Surg 254:410–420. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822c9dac discussion 420–2

Pratt GM, Learn CA, Hughes GD, Clark BL, Warthen M, Pories W (2009) Demographics and outcomes at American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Centers of Excellence. Surg Endosc 23:795–799. doi:10.1007/s00464-008-0077-8

Ahmed AR, Rickards G, Husain S, Johnson J, Boss T, O’Malley W (2007) Trends in internal hernia incidence after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 17:1563–1566. doi:10.1007/s11695-007-9260-6

Higa KD, Ho T, Boone KB (2003) Internal hernias after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: incidence, treatment and prevention. Obes Surg 13:350–354. doi:10.1381/096089203765887642

Iannelli A, Facchiano E, Gugenheim J (2006) Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg 16:1265–1271. doi:10.1381/096089206778663689

Aghajani E, Jacobsen HJ, Nergaard BJ, Hedenbro JL, Leifson BG, Gislason H (2012) Internal hernia after gastric bypass: a new and simplified technique for laparoscopic primary closure of the mesenteric defects. J Gastrointest Surg 16:641–645. doi:10.1007/s11605-011-1790-5

Iannelli A, Buratti MS, Novellas S, Dahman M, Amor IB, Sejor E, Facchiano E, Addeo P, Gugenheim J (2007) Internal hernia as a complication of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 17:1283–1286. doi:10.1007/s11695-007-9229-5

Nguyen NT, Goldman C, Rosenquist CJ, Arango A, Cole CJ, Lee SJ, Wolfe BM (2001) Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: a randomized study of outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg 234:279–289 discussion 289–91

Carucci LR, Turner MA, Shaylor SD (2009) Internal hernia following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity: evaluation of radiographic findings at small-bowel examination. Radiology 251:762–770. doi:10.1148/radiol.2513081544

Sanmugalingam N, Nizar S, Vasilikostas G, Reddy M, Wan A (2013) Does closure of the mesenteric defects during antecolic laparoscopic gastric bypass for morbid obesity reduce the incidence of symptomatic internal herniation? Int J Surg 11:200–202. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.01.005

Comeau E, Gagner M, Inabnet WB, Herron DM, Quinn TM, Pomp A (2004) Symptomatic internal hernias after laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc 19:34–39. doi:10.1007/s00464-003-8515-0

Steele KE, Prokopowicz GP, Magnuson T, Lidor A, Schweitzer M (2008) Laparoscopic antecolic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with closure of internal defects leads to fewer internal hernias than the retrocolic approach. Surg Endosc 22:2056–2061. doi:10.1007/s00464-008-9749-7

Leyba JL, Navarrete S, Navarrete Llopis S, Sanchez N, Gamboa A (2012) Laparoscopic technique for hernia reduction and mesenteric defect closure in patients with internal hernia as a postoperative complication of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 22:e182–e185. doi:10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182550479

Hope WW, Sing RF, Chen AY, Lincourt AE, Gersin KS, Kuwada TS, Heniford BT (2010) Failure of mesenteric defect closure after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Jsls 14:213–216. doi:10.4293/108680810X12785289144151

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the multi-disciplinary team of medical students, physicians, nurses, and dieticians at the Stanford Bariatric and Metabolic Interdisciplinary clinic for their support throughout this clinical investigation.

Disclosures

Dr. John Morton is a consultant for Ethicon and Covidien. Dr. Homero Rivas is a consultant for Ethicon. Ulysses Rosas, Natalia Leva, Trit Garg, and Drs. Shusmita Ahmed, Michael Russo, and James Lau have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosas, U., Ahmed, S., Leva, N. et al. Mesenteric defect closure in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 29, 2486–2490 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3970-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3970-3