Abstract

Background

While the safety of many bariatric procedures has been previously studied in older patients, we examine the effect of advancing age on medical/surgical complications in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, a relatively unstudied procedure but that is trending upwards in use.

Methods

Patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic gastric bypass (RYGB) were extracted from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program 2005–2012 database. Pre- and postoperative variables were analyzed using chi-square and student t test as appropriate to determine the comparative safety of LSG to RYGB in the elderly. Multivariate regression modeling was used to evaluate whether age is associated with adverse 30-day events following LSG.

Results

Of the patients that met the inclusion criteria, 56,664 (84 %) patients underwent RYGB and 10,835 (16 %) underwent LSG. In the LSG cohort, incidence of overall complications, medical complications, and death significantly increased with increasing age (p < 0.05). No statistically significant differences in rates of 30-day complications, return to the OR, and mortality exist between RYGB and LSG cohorts in patients older than 65 years. The age group of over 65 years independently predicted increased risk for overall and medical complications (OR, 1.748; OR, 2.027). Notably, age was not significantly associated with surgical complications in LSG.

Conclusion

In this large, multi-institutional study, advanced age was significantly associated with overall and medical complications but not surgical complications in LSG. Our findings suggest that the risk conferred by advancing age in LSG is predominantly for medical morbidity and advocate for improved perioperative management of medical complications. LSG may be the preferable option to RYGB for elderly patients as neither procedure is riskier with regards to 30-day morbidity while LSG has been shown to be safer with regards to long-term reoperation and readmission risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Age is well recognized as a risk factor in risk stratification models for perioperative morbidity and mortality following bariatric procedures [1–5]. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), originally a component of the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure, is gradually gaining popularity over other bariatric procedures and, since 2012, has been indicated by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery as an acceptable option as a primary bariatric procedure and as a first stage procedure in high-risk patients based on the previous data reported on its efficacy and safety. While studies have reported on the relative effectiveness of LSG, little has been done regarding the comparative safety of LSG among other laparoscopic bariatric procedures [6–13]. Since their last update of their position on LSG, the ASBMS has specifically encouraged new reports on LSG outcomes to better understand the risk/benefit profile of this surgical modality. Even fewer multi-institutional observational studies have examined the safety of LSG in the elderly population, and they are limited by their inability to isolate age as an independent predictor of early morbidity [14, 15].

In 2012, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that decisions regarding LSG coverage will be relegated to the regional Medicare Administrative Contractors, further suggesting the importance of evidence to refute or support perioperative safety of LSG. Thirty-five percent of patients older than 60 years of age suffer from obesity and the prevalence of obesity will surely trend upwards, increasing the volume of bariatric surgeries. For the aforementioned reasons and because the complication profiles in the elderly undergoing surgery has been a recent active area of investigation [16–19], we performed a retrospective analysis via the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) to determine the comparative safety of LSG relative to other laparoscopic bariatric procedures in the elderly and to identify whether age is independently associated with perioperative risk after LSG.

Methods

Patients

The ACS-NSQIP registry from 2005 to 2012 was retrospectively reviewed. The details of the ACS-NSQIP data collection methods have previously been described in detail and validated [20, 21]. Patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery were identified by current procedural terminology (CPT) codes laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (43644), long-limb laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (43645), and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (43775). The entire dataset was stratified by procedure: laparoscopic gastric bypass (RYGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG). Extracted patients were stratified into groups by their age (19–35, 35–50, 50–65, 65 and over), and all patients younger than 19 years of age and with a BMI of less than 35 kg/m2 were excluded.

Age, race, outpatient status, and BMI were included as part of patient demographics. Clinical characteristics examined included alcohol use, smoking, steroid use, radiotherapy in the prior 90 days, chemotherapy in the prior 30 days, previous operations in the prior 30 days, and ventilator dependence. Surgical case characteristics examined included emergency case status and average operative time. Also identified were comorbidities including diabetes, dyspnea, hypertension, COPD, congestive heart failure, bleeding disorders, history of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), cardiac surgery, stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), hemiplegia, disseminated cancer, and ASA class Table 1.

Primary Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was 30-day complication rates, categorized as surgical, medical, and overall complications. Surgical complications include superficial, deep, and organ space surgical site infections (SSIs) and wound dehiscence as classified by the NSQIP User Guide. Medical complications included pneumonia, unplanned intubation, ventilator dependence greater than 48 h, progressive renal insufficiency, acute renal failure, urinary tract infections, peripheral neurologic deficiency, intraoperative or immediate postoperative transfusion requirement, pulmonary embolism, stroke, coma, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, sepsis, septic shock, and death. Overall complication rates were defined as the total of one or more of the above events tracked by the NSQIP database. Return to the OR was defined as a return to the operating room within 30 days of the primary procedure.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were stratified into four age groups, 19–35, 35–50, 50–65, 65 and over. Patient demographics, comorbidities, and outcomes were assessed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and one-way ANOVA tests for continuous variables.

The association between complications and age in laparoscopic gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy was examined using multivariate analysis. Risk-adjustment of the regression model was performed with the aforementioned preoperative variables. Risk factors with an alpha value less than 0.2 in the bivariate analysis were included in regression model. Hosmer–Lemeshow and C-statistics calculations were performed to evaluate calibration and discrimination of the regression model [22, 23]. An alpha value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all multivariate analyses. All analyses were performed using SPSS, version 22 (Chicago, IL).

Results

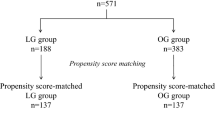

Of the 2,320,920 patients captured in the NSQIP database, 67,499 patients underwent laparoscopic bariatric surgery and met inclusion criteria. About 13,999 (20.7 %) were between 19 and 35 years, 29,413 (43.6 %) were between 35 and 50 years, 21,588 (32.0 %) were between 50 and 65 years, and 2499 (3.7 %) were older than 65 years. About 56,664 (84 %) patients underwent RYGB and 10,835 (16 %) underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Within the group that underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, 2330 patients were between 19 and 35 years, 4889 were between 35 and 50 years, 3313 were between 50 and 65 years, and 303 were older than 65 years of age. Differences in gender, race, age, BMI, diabetes status, smoking, dyspnea, hypertension, previous stroke, previous cardiac surgery, steroid use, bleeding disorders, and ASA class were noted among the age groups.

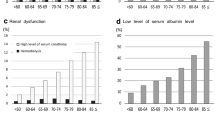

In the LSG cohort, incidence of overall complications, medical complications, and death significantly increased with increasing age (p < 0.05). It is interesting to note that the largest increase in overall and medical complication rate occurred between the 50–65 age group and the 65+ age group. Rate of surgical complications and reoperation did not demonstrate a similar trend (p = 0.456 and 0.18, respectively) (Table 2). In the RYGB cohort, incidence of overall, medical, surgical complications, and mortality was significantly increased with increasing age (p < 0.001). No statistically significant differences in rates of 30-day complications, return to the OR, and mortality exist between RYGB and LSG cohorts in patients older than 65 years (Table 3).

Multivariate regression models were constructed to assess the independent relationship between perioperative complications and advancing age in patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (Table 4). The age group of over 65 years independently predicted increased risk for overall and medical complications (OR, 1.748; OR, 2.027). Notably, age was not significantly associated with surgical complications in LSG. C-statistics and Hosmer–Lemeshow statistics have been included in Table 5 to validate discriminatory capability and calibration of the regression models that were constructed.

Discussion

Our current work, which addresses the paucity of literature on the indications of LSG use in the elderly, investigated the perioperative risk associated with advancing age in LSG. Our multi-institutional retrospective study identified, via multivariate analysis, the 65+ age group undergoing LSG as an independent predictor of medical and overall complications, but not surgical complications.

We demonstrated a significant association between the age group 65+ and increased risk of medical and overall complications in LSG. Surgical complication, which has been previously described as a primary cause of perioperative morbidity [10], was not found to be independently associated with advanced age. The findings in our study should be interpreted in the context of its methodology. High comorbidity burden and male predominance in the elderly cohort may influence their greater predisposition to 30-day medical/overall complications and mortality [24]. Our regression analysis adjusts for these potentially confounding factors, allowing us to evaluate the independent effect of advancing age on postoperative morbidity. A matched analysis, which balances the disparate comorbidity burden and demographic profiles across age groups, may allow for a more rigorous comparison. To our knowledge, there is very little in the literature regarding matching non-binary treatment effects (four age groups). This is a technique that future research may explore. Our findings suggest that postoperative morbidity in patients over 65 years undergoing LSG is attributed to medical complications. Effort should be directed towards the perioperative management and prevention of these complications.

Another important finding of our study, which compared 56,664 RYGB patients to 10,835 LSG patients, was that no statistically significant difference in 30-day rates of complications, return to OR, or mortality existed between the two procedures. While the benefits of LSG such as increased type 2 diabetes mellitus remission, improved satiety, reduced hunger, and long-term weight loss have been described, comparatively less is known about its associated risks [25–27]. Because the use of LSG is only recently trending upwards, the ability to perform robust, retrospective analysis on LSG outcomes is limited by the number of patients. Hutter et al. reported lower risk-adjusted reoperation/intervention rates in 944 patients undergoing LSG compared to 26,684 patients undergoing RYGB [9]. Birkmeyer et al., among other studies that endorsed the safety of LSG, demonstrated a similar reduction in complication rate in 854 LSG patients relative to a larger RYGB cohort [10, 28, 29]. Our study, which evaluated the comparative safety of LSG to other laparoscopic procedures in a large national patient sample, did not find a statistically significant difference in 30-day complications, reoperations, and death between laparoscopic gastric bypass and LSG cohorts in patients older than 65 years. It is possible that our study of over 10,000 LSG patients may more powerfully elucidate the complication profile of the procedure and also demonstrate the variable influence of age on comparative safety. In short, LSG does not seem to be any riskier or safer than RYGB for the elderly. We performed a univariate comparative analysis, which does not adjust for potential confounding variables that may affect 30-day rates of complications. We argue that dissimilar comorbidity burden may not distort the conclusions of our univariate analysis, as the proportions of patients 65 and over who were ASA Class 3, 4, or 5 in either cohort were not significantly different via chi square analysis (52.6 vs. 54.3 %; p = 0.130). An important future direction will be to focus on the effect of surgical modality on postoperative morbidity, independent of any differences in patient characteristics, of which comorbidity burden is not one. Taken together, our findings suggest that age should not be a determining factor in the decision to choose between these two bariatric procedures. As more LSG procedures are performed, future retrospective studies will revisit its comparative risk.

Flum et al. assessed perioperative risk in elderly patients undergoing bariatric surgery (excluding laparoscopic procedures) via Medicare claims data and reported that the risk of early death was associated with advancing age (65+) [30]. Unlike this study, ours is not dependent on Medicare claims data and identifies and controls for multiple variables that may confound the relationship between advancing age and perioperative risk. Because of the improved safety of laparoscopic bariatric procedures over open procedures and the trending use of the laparoscopic technique in the elderly, Dorman et al. performed a similar ACS-NSQIP study that examined age in both open and laparoscopic procedures [3]. Via data from 2006–2009, Dorman et al. reported increased length of stay and death in patients over 65 years undergoing open and laparoscopic procedures and no significant change in 30-day complications. This study excluded laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy procedures, a procedure that is trending upwards but one that CMS has yet to make a definite ruling regarding coverage. Ritz et al. reported no increased in incidence of post-LSG surgical and non-surgical complications in 164 patients above 60 years compared to 1379 patients below 40 years. Their findings advocated LSG as a potentially safer procedure compared to RYGB in the elderly [14]. To date, a consensus in the literature does not exist regarding the perioperative safety of bariatric surgery in the elderly [31–33].

We have demonstrated that advanced age is independently associated with overall and medical complications but not surgical complications. Concurrently, we identified other risk factors for 30-day overall complication, including inpatient status, hypertension, dyspnea, and operation time. The NSQIP dataset robustly captures over 50 preoperative variables of which their respective associations with 30-day morbidity can be assessed with proper risk adjustment. We argue that age should be considered in the context of the other putative risk factors when risk stratifying patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric procedures. Three multi-institutional studies recently published predictive risk models for mortality and morbidity after bariatric surgery that incorporates age as a predictive factor [1, 2, 34]. The development of an interactive individualized risk calculator that estimates 30-day risk of complication that is based on patient demographics and comorbidities and takes into account multiple surgical modalities (i.e., bypass, banding, and sleeve gastrectomy) will be an important future direction.

This study is not without limitations. While the ACS NSQIP dataset provides a robust platform for retrospective analysis, it does not provide procedure specific outcomes such as strictures, anastomotic leaks, and marginal ulcers. Data on the quality of life years saved, which could provide insight into the efficacy of bariatric surgery in the elderly, is not available. In addition, we are unable to capture the entire the postoperative complication profile of each patient because of the 30-day follow-up limit. The method by which we stratified age groups is somewhat arbitrary and may affect the conclusions that we draw, although it has been previously used [3]. The possibility of selection bias cannot be ignored, as comorbidity burden may predispose patients to what procedure they receive. Unfortunately, the reason for choosing a particular procedure is not documented in the database.

Conclusion

Bariatric surgery is an acceptably safe procedure with a 30-day mortality rate of 0.7 and 0.5 % for patients over 65 years of age undergoing LSG and RYGB, respectively. In light of a paucity of literature regarding the safety of LSG in the elderly, our study performed a robust, retrospective analysis on over 10,000 patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) to determine its risk profile in the elderly. Our findings suggest that the risk conferred by advancing age in LSG is predominantly for medical morbidity and advocate for improved perioperative management of medical complications. LSG may be the preferable option to RYGB for elderly patients as neither procedure is riskier with regards to 30-day morbidity while LSG has been shown to be safer with regards to long-term reoperation risk.

References

Gupta PK et al. Development and validation of a bariatric surgery morbidity risk calculator using the prospective, multicenter NSQIP dataset. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(3):301–9.

Ramanan B et al. Development and validation of a bariatric surgery mortality risk calculator. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(6):892–900.

Dorman RB et al. Bariatric surgery outcomes in the elderly: an ACS NSQIP study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(1):35–44. discussion 44.

DeMaria EJ et al. Validation of the obesity surgery mortality risk score in a multicenter study proves it stratifies mortality risk in patients undergoing gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2007;246(4):578–82. discussion 583–4.

Varela JE, Wilson SE, Nguyen NT. Outcomes of bariatric surgery in the elderly. Am Surg. 2006;72(10):865–9.

Carlin AM et al. The comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2013;257(5):791–7.

Trastulli S et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy compared with other bariatric surgical procedures: a systematic review of randomized trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(5):816–29.

Bellanger DE, Greenway FL. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, 529 cases without a leak: Short-term results and technical considerations. Obes Surg. 2011;21(2):146–50.

Hutter MM et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Ann Surg. 2011;254(3):410–20. discussion 420–2.

Birkmeyer NJ et al. Hospital complication rates with bariatric surgery in Michigan. JAMA. 2010;304(4):435–42.

Menenakos E et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy performed with intent to treat morbid obesity: a prospective single-center study of 261 patients with a median follow-up of 1 year. Obes Surg. 2010;20(3):276–82.

Sanchez-Santos R et al. Short- and mid-term outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: the experience of the Spanish National Registry. Obes Surg. 2009;19(9):1203–10.

Helmio M et al. Comparison of short-term outcome of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass in the treatment of morbid obesity: a prospective randomized controlled multicenter SLEEVEPASS study with 6-month follow-up. Scand J Surg. 2014;103(3):175–81.

Ritz P, et al. Benefits and risks of bariatric surgery in patients aged more than 60 years. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014.

Spaniolas K et al. Early morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass in the elderly: a NSQIP analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(4):584–8.

Lynch J, Belgaumkar A. Bariatric surgery is effective and safe in patients over 55: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2012;22(9):1507–16.

Turrentine FE et al. Surgical risk factors, morbidity, and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):865–77.

Yanquez FJ et al. Synergistic effect of age and body mass index on mortality and morbidity in general surgery. J Surg Res. 2013;184(1):89–100.

Curiel-Balsera E et al. Mortality and complications in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Crit Care. 2013;28(4):397–404.

Birkmeyer JD et al. Blueprint for a new American College of Surgeons: National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(5):777–82.

Henderson WG, Daley J. Design and statistical methodology of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: why is it what it is? Am J Surg. 2009;198(5 Suppl):S19–27.

Merkow RP et al. Relevance of the c-statistic when evaluating risk-adjustment models in surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(5):822–30.

Paul P, Pennell ML, Lemeshow S. Standardizing the power of the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test in large data sets. Stat Med. 2013;32(1):67–80.

Finks JF et al. Predicting risk for venous thromboembolism with bariatric surgery: results from the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Ann Surg. 2012;255(6):1100–4.

Lee WJ et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011;146(2):143–8.

Karamanakos SN et al. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective, double blind study. Ann Surg. 2008;247(3):401–7.

Himpens J, Dapri G, Cadiere GB. A prospective randomized study between laparoscopic gastric banding and laparoscopic isolated sleeve gastrectomy: Results after 1 and 3 years. Obes Surg. 2006;16(11):1450–6.

Li JF et al. Comparison of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity or type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Surg. 2013;56(6):E158–64.

Peterli R et al. Early results of the Swiss Multicentre Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS): a prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2013;258(5):690–4. discussion 695.

Flum DR et al. Early mortality among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1903–8.

O'Keefe KL, Kemmeter PR, Kemmeter KD. Bariatric surgery outcomes in patients aged 65 years and older at an American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Center of Excellence. Obes Surg. 2010;20(9):1199–205.

Livingston EH et al. Male gender is a predictor of morbidity and age a predictor of mortality for patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery. Ann Surg. 2002;236(5):576–82.

Sugerman HJ et al. Effects of bariatric surgery in older patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):243–7.

Finks JF et al. Predicting risk for serious complications with bariatric surgery: Results from the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Ann Surg. 2011;254(4):633–40.

Financial Support

This particular research received no internal or external grant funding.

Ethical Approval

De-identified patient information is freely available to all institutional members who comply with the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) Data Use Agreement. The Data Use Agreement implements the protections afforded by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and the ACS-NSQIP Hospital Participation Agreement, and conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclaimer

The NSQIP and the hospitals participating in the NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not been verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis, or the conclusions derived by the authors of this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, C., Luo, B., Aggarwal, A. et al. Advanced Age as an Independent Predictor of Perioperative Risk after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy (LSG). OBES SURG 25, 406–412 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1462-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1462-0