Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG) might have greater clinical benefits for elderly patients as less invasive surgery; however, there is still little evidence to support its benefit. We evaluated the surgical outcomes of elderly patients in a nationwide prospective cohort study.

Methods

One hundred and sixty-nine participating institutions were identified by stratified random sampling, and were adjusted for hospital volume, type and location. During 1 year from 2014 to 2015, consecutive patients who underwent gastrectomy for gastric cancer were prospectively enrolled. ‘Elderly’ was defined as ≥ 75 years of age, based on the prevalence of comorbidities and the activities of daily living of patients of this age. We compared the surgical outcomes of LG to those of open gastrectomy (OG) in non-elderly and elderly patients. The primary outcome was the incidence of severe morbidities (Grade ≥ 3).

Results

Eight thousand nine hundred and twenty-seven patients were enrolled [non-elderly, n = 6090 (OG, n = 2602; LG, n = 3488); elderly, n = 2837 (OG, n = 1471; LG, n = 1366)]. Grade ≥ 3 complications occurred in 161 (10.9%) patients who underwent OG and 98 (7.2%) who underwent LG (p < 0.001). After adjusting for confounding factors, we confirmed that laparoscopic surgery was not an independent risk factor (odds ratio = 0.81, 0.60–1.09). OG was associated with a significantly longer median length of postoperative stay in comparison to LG (16 versus 12 days, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in the incidence of other postoperative comorbidities.

Conclusion

The safety of LG in elderly patients was demonstrated. LG shortened the length of postoperative hospital stay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The aging population problem has been a major concern in developed countries. Japan, where the average life expectancy has increased while birth rates have fallen during the last quarter-century, leads the world in this issue [1]. Surgical treatment with general anesthesia is generally considered to be associated with a high risk of postoperative complications in elderly patients [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The main reason is the higher prevalence of cardiac, pulmonary and other comorbidities in older patients [8, 9]. Although some surgeons suggest that less invasive surgery, such as laparoscopic surgery, is of greater benefit in elderly patients [10,11,12], our previous survey on gastric cancer surgery using a national clinical database (NCD) have shown that surgeons tend to select open surgery for elderly patients [13,14,15,16]. Several clinical trials have demonstrated that the surgical outcomes of laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG) are similar or superior to those of open gastrectomy (OG) for patients with gastric cancer [17,18,19,20,21]; however, there is still little evidence of the efficacy and safety in elderly patients in routine clinical practice [22,23,24].

In the present study, we sought to address two research questions: can LG be performed safely in elderly patients and what kind of clinical benefit does LG have in this patient group? Our hypothesis was that the surgical risk of LG would not be higher than that of OG in terms of postoperative complications in elderly patients. To verify this hypothesis and explore the potential clinical benefits of LG, we conducted a multicenter prospective cohort study based on an NCD system that covered more than 90% of the general surgery operations performed in Japan. We then confirmed the safety and explored the clinical benefits of LG in elderly patients, in comparison to conventional OG. Through this study, we hope to provide relevant information for selecting a suitable surgical approach for the treatment of gastric cancer in elderly patients.

Methods

Study design and cohort development

The study design was a prospective cohort study. The method of cohort development was reported previously [14]. In brief, target institutions were selected from users of the NCD system by stratified random sampling. Adjustment was performed for the hospital volume (number of surgical cases per year), hospital type (university hospital, specialized hospital, and others), and location (10 regions and 3 urban levels), then random sampling was performed to select a cohort of institutions that represented the state of the country. A request to participate was sent to 179 institutions, 169 ultimately cooperated. During 1 year from August 2014 to July 2015, consecutive patients who underwent gastrectomy for gastric cancer were prospectively enrolled. Patients who underwent concurrent operations other than cholecystectomy were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board; all study procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the respective committees on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions.

Definition of ‘elderly’

To determine the cut-off age for ‘elderly’, we evaluated the relationship between age and the surgical and anesthesiologic risks in the patients in this dataset. The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a history of ischemic heart disease, chronic heart failure, insulin-dependent diabetes, hypertension and peripheral arterial disease was evaluated at each age. The patients’ activities of daily living were classified into three categories: independent, partially assisted or completely assisted living. In addition, considering the cut-off point from the perspective of surgical decision making, we also analyzed the relationship between age and the actual proportion of patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery in our dataset.

Data collection

We assumed that many confounding factors would affect the comparison of LG and OG. As potential confounding factors, our study team identified and collected some variables related to decision-making with regard to the performance of LG or OG, as covariates from clinical and statistical perspectives, including age, sex, the American Society of Anesthesiologists Performance Status (ASA-PS) score, body mass index (BMI), presence of comorbidities, history of abdominal surgery, clinical TNM stage, degree of lymphadenectomy, resection area and reconstruction procedure.

Outcomes and statistics

The primary endpoint was the incidence of grade ≥ 3 complications. A logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) of laparoscopic surgery after adjusting for confounding factors as the primary endpoint. Covariates inserted in this logistic model were as follows: sex, BMI, ASA-PS score, respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic pulmonary disease, hypertension, bleeding disorder, emergency, preoperative chemotherapy, D2 lymph node dissection, TNM stage, and resection area. Some of these variables were newly collected for this study in addition to the conventional list of variables in the NCD gastroenterology registry system. In addition, the interaction between age and the surgical approach was also confirmed. The secondary endpoints included mortality within 30 days, the length of postoperative stay, conversion to open surgery, operative time and blood loss. To compare these outcomes between the two surgical approaches, Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze binary variables in which the expected cell count was < 5, and Pearson’s chi-squared test was used for the analysis of other variables. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for continuous variables. Comparisons were all two-sided and p values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SAS software program (ver. 9.4, SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The definition of ‘elderly’

Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate the relationship between patient age and the prevalence of comorbidities and laparoscopic surgery, respectively. Although it was difficult to decide on a clear threshold for the definition of ‘elderly’, our team selected 75 years as the cut-off age in the present study.

The prevalence rate of preoperative comorbidities and activities of daily living. a The prevalence of cardio-vascular disease: chronic heart failure (CHF), myocardial infarction (MI) and peripheral vascular disease (PVD). b The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. c The prevalence of renal dysfunction; high level of serum creatinine and hemodialysis. d Nutrition status: proportion of serum albumin level. e The proportion of patients with ADL self-support

The study population and patient characteristics

We identified 2837 (37.3%) elderly patients from all patients who underwent gastrectomy (n = 8927) in the participating institutions during the study period. Table 1 demonstrates the characteristics of the non-elderly and elderly groups, respectively. Patients undergoing OG were more likely to be older, with a poorer ASA-PS, and to have a more advanced TMM stage in comparison to patients undergoing LG.

Primary outcome

Table 2 shows the surgical procedures and outcomes of non-elderly and elderly patients. In both groups, we found a higher incidence of postoperative complications in patients who underwent OG than in those who underwent LG: 8.8% vs. 5.2% (p < 0.001) in the non-elderly and 10.9% vs. 7.2% (p < 0.001) elderly groups. After adjustment for confounding factors (using the logistic regression model), laparoscopic surgery was not an independent risk factor in either group. Table 3 shows the odds ratios and 95% CIs of the variables. Furthermore, no interaction between age and laparoscopic surgery was seen in this model (OR 0.97; 95% CI 0.69–1.36). Aside from the surgical approaches, respiratory disease, bleeding disorder and total gastrectomy were independent risk factors in elderly patients.

Secondary outcomes

In both groups, OG was associated with a longer mean length of postoperative stay. As expected, the mean operating time of LG was significantly longer in comparison to OG, while the amount of blood loss in OG was significantly greater in comparison to LG. The rate of conversion from LG to OG in the non-elderly and elderly groups did not differ to a statistically significant extent. Pneumonia, intra-abdominal abscess and anastomotic leakage were major complications in elderly patients (Table 4).

Discussion

The results of the present study clarified that laparoscopic surgery was not associated with an increased risk of morbidity in elderly or non-elderly patients with gastric cancer. In our cohort, LG tended to be selected for female patients, younger patients, and patients with earlier disease and a better performance status. Thus, through the process of adjusting for these confounding factors, our primary goal was achieved: the safety of LG relative to OG in elderly patients was confirmed. In addition, LG shortened the length of postoperative hospital stay by an average of 4 days in elderly patients. Considering these results, we consider LG to have a certain clinical benefit as less invasive surgery in elderly patients.

LG can be performed with a small incision on the abdominal wall and with a very small volume of blood loss; however, it takes approximately 1 h longer than OG. Our clinical question was: which surgical approach achieved better outcomes in elderly patients? In real-world practice in Japan (Fig. 2), surgeons tend to prefer OG to LG for elderly patients; however, this choice might not always be appropriate. One of the more notable findings in the present study was that the incidence of pancreatic fistula did not differ markedly between LG and OG in the elderly group. This conflicts with our previous finding that pancreatic fistula frequently occurred in patients who underwent LG [14, 25]. This may suggest that most surgeons tended to refrain from performing lymph node dissection in the peri-pancreatic area for elderly patients to save operative time and avoid complications. In addition, the amount of visceral fat tissue in elderly patients—which is lower than in middle-aged patients—might be related to lower incidence of pancreatic fistula. We also confirmed that bleeding disorder and respiratory disease were specific risk factors in the elderly population but not younger patients. Patients who received antithrombotic treatment with an antiplatelet agent or anticoagulant for cardio- or cerebrovascular disease were more common among elderly patients than among younger ones, highlighting the need to perform more careful manipulation during operation and perioperative management in older patients.

The definition of ‘elderly’ is an issue, whenever the treatment of elderly patients is discussed. The reason why the elderly population is excluded from most pharmacological trials is that their physiological capability, with regard to drug metabolism and hemodynamics (i.e., their liver, renal and cardiac function), may deteriorate as they grow older. Thus, the efficacy and adverse events of drugs may become more difficult to evaluate in elderly patients. When evaluating a specific type of surgery, therefore, we might need to consider the risks of general anesthesia and surgical complications and determine the cut-off age for the definition of ‘elderly’ in each study. One of the challenges in our study was determining the cut-off age from the perspective of operative risk and patient comorbidities. Although it was difficult to clearly define the threshold in the present population, we confirmed that the cut-off age of 75 years showed a certain degree of validity.

This study is the first and largest size prospective cohort study to focus on surgery for elderly gastric cancer patients. We believe that our results are useful and reliable for surgeons who treat gastric cancer patients. However, this study was associated with some limitations. Postoperative symptoms, quality of life and physical activities remain the most clinically relevant issues in relation to surgery for elderly patients. Malnutrition, which develops in relation to sequelae after gastrectomy, causes the deterioration of other comorbidities and the progression of disuse syndrome in some elderly patients. Furthermore, the most common cause of other death was pneumonia in elderly patients who underwent gastrectomy [26]. Although we did not monitor long-term events, preoperative respiratory disease was found to be an independent risk for complications in the elderly group. Surgeons should, therefore, pay attention to patients’ respiratory assessment findings in both the short and long terms. In future studies, we should evaluate the impact of less invasive surgery not only on the short-term outcomes of elderly patients but also on their mid- and long-term complication, nutrition status, quality of life and daily activities.

In conclusion, the safety of laparoscopic gastrectomy for elderly patients was demonstrated in this nationwide prospective cohort study.

References

Health_Labor_and_Welfare” M. Vital Statistics in Japan—The latest trend [Japanese]. 2018. https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/dl/index.html. Accessed 10 June 2018.

Sandini M, Pinotti E, Persico I, Picone D, Bellelli G, Gianotti L. Systematic review and meta-analysis of frailty as a predictor of morbidity and mortality after major abdominal surgery. BJS Open. 2017;1:128–37.

Gupta PK, Gupta H, Sundaram A, Kaushik M, Fang X, Miller WJ, et al. Development and validation of a risk calculator for prediction of cardiac risk after surgery. Circulation. 2011;124:381–7.

Kneuertz PJ, Pitt HA, Bilimoria KY, Smiley JP, Cohen ME, Ko CY, et al. Risk of morbidity and mortality following hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1727–35.

Soveri I, Holme I, Holdaas H, Budde K, Jardine AG, Fellstrom B. A cardiovascular risk calculator for renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2012;94:57–62.

Abete P, Cherubini A, Di Bari M, Vigorito C, Viviani G, Marchionni N, et al. Does comprehensive geriatric assessment improve the estimate of surgical risk in elderly patients? An Italian multicenter observational study. Am J Surg. 2016;211:76–83e2.

Stornes T, Wibe A, Endreseth BH. Complications and risk prediction in treatment of elderly patients with rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:87–93.

Kenig J, Mastalerz K, Mitus J, Kapelanczyk A. The Surgical Apgar score combined with Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment improves short- but not long-term outcome prediction in older patients undergoing abdominal cancer surgery. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9(6):642–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2018.05.012.

Kim SW, Han HS, Jung HW, Kim KI, Hwang DW, Kang SB, et al. Multidimensional frailty score for the prediction of postoperative mortality risk. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:633–40.

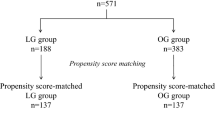

Yamamoto M, Shimokawa M, Kawano H, Ohta M, Yoshida D, Minami K, et al. Benefits of laparoscopic surgery compared to open standard surgery for gastric carcinoma in elderly patients: propensity score-matching analysis. Surg Endosc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6325-7.

Shimada S, Sawada N, Oae S, Seki J, Takano Y, Ishiyama Y, et al. Safety and curability of laparoscopic gastrectomy in elderly patients with gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(10):4277–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6177-1.

Zong L, Wu A, Wang W, Deng J, Aikou S, Yamashita H, et al. Feasibility of laparoscopic gastrectomy for elderly gastric cancer patients: meta-analysis of non-randomized controlled studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8:51878–87.

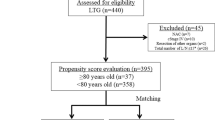

Etoh T, Honda M, Kumamaru H, Miyata H, Yoshida K, Kodera Y, et al. Morbidity and mortality from a propensity score-matched, prospective cohort study of laparoscopic versus open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: data from a nationwide web-based database. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:2766–73.

Hiki N, Honda M, Etoh T, Yoshida K, Kodera Y, Kakeji Y, et al. Higher incidence of pancreatic fistula in laparoscopic gastrectomy. Real-world evidence from a nationwide prospective cohort study. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:162–70.

Kodera Y, Yoshida K, Kumamaru H, Kakeji Y, Hiki N, Etoh T, et al. Introducing laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer in general practice: a retrospective cohort study based on a nationwide registry database in Japan. Gastric cancer. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-018-0795-0.

Yoshida K, Honda M, Kumamaru H, Kodera Y, Kakeji Y, Hiki N, et al. Surgical outcomes of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy compared to open distal gastrectomy: a retrospective cohort study based on a nationwide registry database in Japan. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;2:55–64.

Katai H, Sasako M, Fukuda H, Nakamura K, Hiki N, Saka M, et al. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with suprapancreatic nodal dissection for clinical stage I gastric cancer: a multicenter phase II trial (JCOG 0703). Gastric cancer. 2010;13:238–44.

Kim HH, Hyung WJ, Cho GS, Kim MC, Han SU, Kim W, et al. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an interim report–a phase III multicenter, prospective, randomized Trial (KLASS Trial). Ann Surg. 2010;251:417–20.

Haverkamp L, Brenkman HJ, Seesing MF, Gisbertz SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Luyer MD, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer, a multicenter prospectively randomized controlled trial (LOGICA-trial). BMC Cancer. 2015;15:556.

Sakuramoto S, Yamashita K, Kikuchi S, Futawatari N, Katada N, Watanabe M, et al. Laparoscopy versus open distal gastrectomy by expert surgeons for early gastric cancer in Japanese patients: short-term clinical outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1695–705.

Lee JH, Kim YW, Ryu KW, Lee JR, Kim CG, Choi IJ, et al. A phase-II clinical trial of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3148–53.

Wang JF, Zhang SZ, Zhang NY, Wu ZY, Feng JY, Ying LP, et al. Laparoscopic gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for elderly patients with gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:90.

Pan Y, Chen K, Yu WH, Maher H, Wang SH, Zhao HF, et al. Laparoscopic gastrectomy for elderly patients with gastric cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97:e0007.

Shen Y, Hao Q, Zhou J, Dong B. The impact of frailty and sarcopenia on postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing gastrectomy surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:188.

Tsujiura M, Hiki N, Ohashi M, Nunobe S, Kumagai K, Ida S, et al. “Pancreas-Compressionless Gastrectomy”: a Novel Laparoscopic Approach for Suprapancreatic Lymph Node Dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3331–7.

Suzuki S, Kanaji S, Matsuda Y, Yamamoto M, Hasegawa H, Yamashita K, et al. Long-term impact of postoperative pneumonia after curative gastrectomy for elderly gastric cancer patients. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;2:72–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the respective committees on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cancer Institute Hospital, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Kodera reports grants and personal fees from Taiho Pharmaceutical, grants and personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, grants from Sanofi, grants from Merck Serono, grants and personal fees from Yakult Honsha, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, grants and personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Factory, grants from Takeda Pharmaceutical, personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, personal fees from Asahi Kasei Pharma, grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly Japan, grants from Pfizer Japan, grants from EA Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from ONO Pharmaceutical, grants and personal fees from Kaken Pharmaceutical, grants from Covidien Japan, grants from Shionogi, grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, grants from Japan Blood Products Organization, grants from AbbVie GK, grants from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, grants from Eizai, grants from Abbott Japan, grants from CSL Behring, grants from Tsumura, grants from Nippon Kayaku, grants from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Japan, grants from KCI, grants from Maruho, personal fees from MSD, outside the submitted work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Honda, M., Kumamaru, H., Etoh, T. et al. Surgical risk and benefits of laparoscopic surgery for elderly patients with gastric cancer: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Gastric Cancer 22, 845–852 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-018-0898-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-018-0898-7