Abstract

Introduction

An increasing body of evidence is being published about single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC), but there are no well-powered trials with an adequate evaluation of post-operative pain. This randomized trial compares SILC against four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) with post-operative pain as the primary endpoint.

Methods

Hundred patients were randomized to either SILC (n = 50) or LC (n = 50). Exclusion criteria were (1) Acute cholecystitis; (2) ASA 3 or above; (3) Bleeding disorders; and (4) Previous open upper abdominal surgery. Patients and post-operative assessors were blinded to the procedure performed. The site and severity of pain were compared at 4 h, 24 h, 14 days and 6 months post-procedure using the visual analog scale; non-inferiority was assumed when the lower boundary of the 95 % confidence interval of the difference was above −1 and superiority when p ≤ 0.05.

Results

The study arms were demographically similar. At 24 h post-procedure, SILC was associated with less pain at extra-umbilical sites (rest: p = 0.004; movement: p = 0.008). Pain data were inconclusive at 24 h at the umbilical site on movement; SILC was otherwise non-inferior for pain at all other points. Operating duration was longer in SILC (79.46 vs 58.88 min, p = 0.003). 8 % of patients in each arm suffered complications (p = 1.000). Re-intervention rates, analgesic use, return to function, and patient satisfaction did not differ significantly.

Conclusions

SILC has improved short-term pain outcomes compared to LC and is not inferior in both short-term and long-term pain outcomes. The operating time is longer, but remains feasible in routine surgical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nearly 30 years since the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy by German surgeon Erich Mühe [1], we are now witnessing a renewal of interest in further minimizing the invasiveness of routine cholecystectomy. With much of modern surgical research being directed toward single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, it has been hoped that these techniques may offer reduced morbidity and improved cosmesis as compared to conventional laparoscopic techniques [2–8].

Since it was first pioneered by Navarra et al. [9], single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been shown to be both feasible and efficacious as compared to conventional multi-port laparoscopic approaches, with the majority of procedures being completed without adverse events, the addition of further port sites or conversion to open surgery [10–17].

There are, however, few well-powered trials providing a detailed analysis of post-operative pain in SILS cholecystectomy. In this single-institution randomized controlled trial, we compare single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy against the conventional four-port laparoscopic technique with post-operative pain as our primary end point. We hypothesize that the single-incision technique is non-inferior with regard to post-operative pain and may be associated with better cosmesis and a faster return to normal function. This paper presents our final results and carries on from our previously published interim report [18]. We thus present our findings.

Materials and methods

Patient recruitment

Taking a pain score difference of 1 point out of 10 to be clinically significant, we determined that demonstrating non-inferiority between single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the conventional four-port technique with 80 % power would require 50 patients in each study arm.

Inclusion criteria for our study are listed as follows:

-

Age: 21–80 years of age

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score 1 or 2

-

Presence of symptomatic gallstones

-

Informed consent given

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Acute cholecystitis

-

Previous open upper abdominal surgery

-

Bleeding disorders

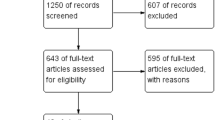

All patients were prospectively recruited from both the inpatient wards and outpatient clinics at a tertiary hospital between October 2010 and March 2012. All patients had valid indications for laparoscopic cholecystectomy and had given informed consent after receiving both verbal and written information regarding our study.

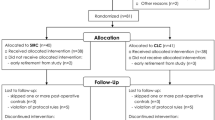

Each patient was randomized to one of two study arms by the closed envelope technique, with one arm undergoing single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) and the other undergoing conventional four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) (Fig. 1). Both patients and post-operative assessors were blinded as to the assigned study arm. The study protocol was approved by our institution’s Domain Specific Review Board (reference number: 2009/00434) and is registered with www.ClinicalTrials.gov (reference number: NCT01824186).

Surgical methodology: single-incision technique

After everting the umbilicus, a longitudinal 2 cm incision was made without extension beyond the umbilical folds. The Covidien (Norwalk, USA) SILS™ port was then inserted with the use of a curved clamp. The Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) EndoEYE™ 5 mm laparoscope was used in view of the in-line profile of its light/camera cables. To improve triangulation, the Covidien (Norwalk, USA) AutoSuture Roticulator™ Endo Grasp™, a disposable articulating laparoscopic instrument, was used.

The fundus of the gallbladder was first retracted toward the anterior abdominal wall by means of a suture sling. Calot’s triangle was then dissected to identify the cystic artery and cystic duct, which were secured with 5 mm plastic clips and divided. Electrocautery was used to dissect the gallbladder off the liver bed, and the gallbladder was then retrieved with a ‘home-made’ plastic bag. Two figure-of-eight Polysorb 1-0 sutures were used to achieve fascial closure. Subcuticular skin closure was achieved with Monocryl 4-0 in an interrupted fashion. The placement of additional ports was considered a conversion to conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Surgical methodology: four-port technique

A 10-mm port (Genicon, Winter Park, FL) was first inserted at the umbilical site via the Hasson technique. Pneumoperitoneum was thence established, and 5 mm laparoscopic ports were introduced at the right flank, right hypochondrium, and the epigastrium under visualization via a rigid 10 mm 30° laparoscope.

Each procedure was performed in accordance with the best judgement and preferences of the individual surgeons.

Peri-operative care

All patients received prophylactic antibiotics at induction of anesthesia; the antibiotic agent was decided as per the best judgement of the attending surgeon and anesthetist. All patients received dressings at the umbilicus, epigastrium, right flank, and the right hypochondrium, regardless of which procedure they had received; this concealed the procedure performed from both the patients as well as the post-operative assessor.

Post-procedure, patients were discharged when appropriate as per standard clinical routines. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is largely conducted as a day procedure at our institution, with the majority of patients being discharged within 24 h of the procedure. All patients were prescribed paracetamol 1 g 6 hourly for 14 days. Dressings over the epigastrium, right hypochondrium, and right flank were kept for a minimum of 24 h post-procedure and were subsequently removed at the patient’s discretion. No further analgesia or anti-emetic was prescribed unless a request was made by the patient. An outpatient follow-up appointment was scheduled at two weeks post-procedure for all patients.

Data collection

Data were collected at the following points: pre-operatively, peri-operatively, 4 h post-procedure, 24 h post-procedure, 2 weeks post-procedure, and 6 months post-procedure.

Patients’ demographic data and diagnoses were recorded prospectively. Immediately after each procedure, the operating duration, operative findings, and intra-operative complications were also recorded. The operating duration was recorded as the time elapsed between the first incision and the completion of skin closure.

Pain, the primary outcome, was measured at 4 and 24 h post-procedure; patients were instructed to indicate the site and severity of their pain on a standardized 10.0 cm unscaled visual analog scale. The severity of pain was measured both at rest and on movement.

At 14 days post-procedure, the site(s) and severity of pain were obtained from the patient via a telephone interview. Discharge timing, complications, and readmissions to hospital were recorded as well. In order to measure return to normal function, the number of days taken to return to activities such as using the toilet and showering independently was recorded, as was number of days taken to obtain meals independently. Also recorded was the total analgesic use, including both inpatient and outpatient consumption.

Patient satisfaction level, both with the cosmetic result and with the overall procedure, was recorded on a Likert scale, with very unsatisfied, unsatisfied, neutral, satisfied, and very satisfied as the available options. The post-operative assessor was blinded to the procedure performed.

Six months post-procedure, a separate telephone interview was carried out by a blinded assessor, who proceeded to enquire regarding post-operative pain, analgesia use, complications, and satisfaction levels, both with the cosmetic result and the overall procedure. With all patients who were lost to our follow-up, the clinical team screened for further procedures, inpatient admissions, and outpatient prescriptions on the Cluster-shared Patient Record System, a nationwide electronic record covering all public healthcare institutions in Singapore. Patients who were lost to follow-up and who had no related healthcare encounters were assumed to be complication free.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 21 (IBM, USA, New York) on an intention-to-treat basis.

Patient demographics and clinical data were analyzed descriptively. Continuous variables were compared between the treatment arms using the two-sample t test or Mann–Whitney U test, where applicable, while categorical variables were compared using the χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. The distribution of patients lost to follow-up was compared with Fisher’s exact test.

Pain was classified as involving the umbilical site or extra-umbilical (including the right hypochondrium, other abdominal sites, and shoulder tip pain) in nature and was measured both at rest and on movement at each time point. The mean reduction in pain in SILC versus LC and the 95 % confidence interval was estimated. Assuming a pain score difference of 1 out of 10 to be clinically significant, non-inferiority was determined with 95 % confidence when the lower boundary of the 95 % confidence interval was greater than −1; superiority on the other hand was determined when p < 0.05.

Analgesic use and post-operative return to function were compared with the Mann–Whitney U test. The use of additional (non-paracetamol) analgesia, the incidence of complications, discharge within 24 h, readmissions to hospital, cosmetic satisfaction, and overall satisfaction were compared using the χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test, where applicable.

Results

51 patients were randomized to SILC (20 males and 31 females), and 50 patients were randomized to LC (20 male, 30 female). One SILC patient withdrew consent for the trial immediately post-operatively; we proceeded to withdraw him from the study and recruited an additional patient for repeat randomization instead. Data from 50 SILC patients and 50 LC patients were available for analysis. Follow-up at 4 h (n = 100), 24 h (n = 99), 14 days (n = 97), and 6 months (n = 93) were available for analysis.

Patient demographics and diagnoses did not differ significantly between the study arms (Table 1). One patient’s BMI was not available, and this value was excluded from our analysis. Of note, one patient in the SILC arm was re-scored as ASA 3 by the anesthetist just prior to surgery; this was not communicated to the surgical team and the patient was not withdrawn from the trial. His data were included in our final analysis as per our intention-to-treat protocol.

All patients received the assigned procedure. Operating duration was significantly longer in SILC than in LC (79.46 vs 58.88 min), with an estimated mean difference of 20.58 min (95 % CI 7.10–34.06, p = 0.003).

Three (6 %) SILC procedures required conversion to conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Of these, one patient had limited visualization of Calot’s triangle due to adhesions and a short cystic duct; this required conversion to a three-port procedure. Another had arterial bleeding during adhesiolysis requiring conversion to a four-port procedure. The last patient had an impacted stone at the junction of the cystic duct and common bile duct, necessitating a three-port procedure for safe removal. Conversion to a multi-port procedure was associated with significantly longer operating times in SILC (124.33 vs 76.60 min, p = 0.04). There were no conversions to open cholecystectomy in either arm.

Regarding post-operative follow-up, one patient in the LC arm was lost to follow-up at the 24 h time point and beyond, and another was lost at the 14-day time point. Two other patients in the LC arm were lost to follow-up at the 6-month time point. In the SILC arm, three patients were lost to follow-up at the 6-month time point. These differences were not statistically significant (24 h p = 1.000 f; 14 days p = 0.495 f; 6 months p = 1.000 f). At the time of analysis, none of these patients had related healthcare encounters on the Cluster-shared Patient Record System.

At 24 h post-procedure, mean umbilical pain at rest was 2.890 in SILC and 2.957 in LC. The mean reduction in pain was +0.067 (95 % CI −0.914–+1.049, p = 0.982), demonstrating the non-inferiority of SILC as the lower boundary of the 95 % CI was greater than −1 (Table 2). On movement, mean umbilical pain was 3.692 in SILC and 3.753 in LC, with a mean reduction in pain of +0.061 (95 % CI −1.049–+1.171, p = 0.913) (Table 2). There was not enough evidence to show the non-inferiority of SILC as the lower bound of the 95 % CI was less than −1.

At extra-umbilical sites at the 24 h time point, mean pain at rest was 0.628 in SILC and 1.898 in LC. The mean reduction in pain was +1.270 (95 % CI +0.430–+2.110; p = 0.004) (Table 2). On movement, mean pain was 1.010 in SILC and 2.361 in LC, with a mean reduction in pain of +1.351 (95 % CI +0.498–+2.341; p = 0.008) (Table 2). This data not only support non-inferiority in SILC in extra-umbilical pain at 24 h post-procedure, but also indicate that SILC was associated with significantly better pain outcomes at extra-umbilical sites at 24 h post-procedure, both at rest and on movement, as compared to LC. Non-inferiority of pain outcomes in SILC was demonstrated at all other time point for both umbilical and extra-umbilical sites, both at rest and on movement (Table 2).

A total of four patients in each arm suffered complications; complication rates, re-intervention rates, and readmission rates were similar in both study arms (Table 3). In LC, one patient experienced cholangitis, requiring therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). One patient re-presented with a seroma in the subhepatic space; this resolved with conservative management. One patient had wound infection requiring parenteral antibiotics, and one other patient suffered post-operative nausea and vomiting.

In SILC, one patient suffered anaphylaxis following induction of anesthesia. The procedure was nonetheless completed uneventfully, but she subsequently re-presented with choledocholithiasis requiring therapeutic ERCP. Another patient in SILC suffered post-operative fluid overload and wound infection during the initial inpatient stay, and later re-presented with cholangitis on computed tomography; there was no evidence of stone disease or obstruction and this resolved with parenteral antibiotics. An incisional hernia was subsequently noted on follow-up, which required laparoscopic repair. These complications were largely attributed to poor pre-morbid characteristics. Two other patients experienced post-operative nausea and vomiting, which resolved with symptomatic treatment. There were no incidents of biliary injury in either arm.

Fewer patients within the SILC arm were discharged within 24 h of surgery as compared with LC, though this was not significant. Analgesic use and return to normal function were similar in both study arms as well (Table 4).

At both 14 days and 6 months post-procedure, satisfaction levels were higher in the SILC arm as compared with the LC arm, both in terms of the cosmetic result of surgery as well as overall satisfaction. This, however, was not statistically significant (Table 5).

Discussion

SILC, promisingly, was demonstrated to be non-inferior to LC in both short-term and long-term pain outcomes and at both umbilical and extra-umbilical sites, regardless of whether the patient was at rest or moving. The only exception was in umbilical pain on movement at the 24 h time point, where pain scores did not differ significantly, but non-inferiority could not be demonstrated. Furthermore, SILC was associated with significantly less extra-umbilical pain at 24 h, both at rest and on movement. In view of the similar analgesic consumption patterns between both study arms, these results not only support the non-inferiority of SILC over LC in both short-term and long-term pain outcomes, but also support an association with reduced short-term pain in extra-umbilical sites in SILC. These findings are encouraging in that other studies have not been able to convincingly demonstrate non-inferiority of both short-term and long-term pain outcomes in SILC over LC [14, 15, 19–22].

Unsurprisingly, we have observed significantly longer operating times in SILC as compared to LC; while the use of articulating instruments and a low-profile laparoscope assisted us with improving triangulation and visualization of the operating field, the narrow angle operating field in SILS is nonetheless technically challenging when compared to conventional approaches. These observed differences in operating duration are consistent with trends noted in other randomized trials and meta-analyses [19–23]. We are, however, of the opinion that the mean operating duration of 79.26 min in SILC compares favorably with the 58.88 min observed in LC and is acceptable for routine cholecystectomy.

While observed complication rates and the need for re-intervention did not differ significantly between study arms, we acknowledge that laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a procedure with an inherently low rate of major complications [24]; appropriate evaluation will require a far larger enrolment. One multicentre trial has thus far observed an increased incidence of incisional hernia in SILC, with rates of 8.4 % at 1 year post-procedure [25]. We have not noted similar events at 6-month follow-up, although further evaluation of our post-operative patients is required. Meta-analyses published, to date, have not found any significant differences between the two techniques thus far [22, 23].

This trial is intended to study pain outcomes primarily. Although we recorded patient satisfaction regarding cosmetic outcomes, assessed with a single question via phone interview, further studies utilising a quality of life instrument or a modified Hollander cosmesis scale may yield further information regarding post-operative cosmesis.

The data from this single-institution randomized trial demonstrate single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy to have an advantage over conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy in terms of post-operative pain, while return to function, cosmesis, patient satisfaction, and complication rates did not differ significantly. We acknowledge, however, that a more detailed assessment of adverse outcomes in SILC will require larger trials and/or meta-analyses.

In view of the improved pain outcomes in SILC, acceptable operating duration and similar complication rates as compared to LC, we believe our results support single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a feasible option in routine surgical practice.

References

Litynski GS (1998) Erich Mühe and the rejection of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (1985): a surgeon ahead of his time. JSLS 2(4):341–346

Horgan S, Cullen JP, Talamini MA et al (2009) Natural orifice surgery: initial clinical experience. Surg Endosc 23(7):1512–1518

Rao PP, Rao PP, Bhagwat SS (2011) Single-incision laparoscopic surgery—current status and controversies. J Minim Access Surg 7(1):6–16

Whang SH, Thaler K (2010) Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery: where are we going? World J Gastroenterol 16(35):4371–4373

Coomber RS, Sodergren MH, Clark J et al (2012) Natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery applications in clinical practice. World J Gastrointest Endosc 4(3):65–74

Cuschieri A (2011) Single-incision laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Access Surg 7(1):3–5

Yuen ABT, Wai PYC, Kwok EWN (2010) Current developments in natural orifices transluminal endoscopic surgery: an evidence-based review. World J Gastroenterol 16(38):4792–4799

Junker H (1974) Laparoscopic tubal ligation by the single puncture technique (author’s translation). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 34:952–955

Navarra G, Pozza E, Occhionorelli S et al (1997) One-wound laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 84:695

Hirano Y, Watanabe T, Uchida T et al (2010) Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: single institution experience and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 16(2):270–274

Rivas H, Varela E, Scott D (2010) Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial evaluation of a large series of patients. Surg Endosc 24(6):1403–1412

Prasad A, Mukherjee KA, Kaul S, Kaur M (2011) Postoperative pain after cholecystectomy: conventional laparoscopy versus single-incision laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Access Surg 7(1):24–27

Romanelli JR, Roshek TB 3rd, Lynn DC, Earle DB (2010) Single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial experience. Surg Endosc 24(6):1374–1379

Tsimoyiannis EC, Tsimogiannis KE, Pappas-Gogos G et al (2010) Different pain scores in single transumbilical incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus classic laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 24(8):1842–1848

Marks J, Tacchino R, Roberts K et al (2011) Prospective randomized controlled trial of traditional laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of preliminary data. Am J Surg 201(3):369–373

Lee PC, Lo C, Lai PS et al (2010) Randomized clinical trial of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus minilaparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 97:1007–1012

Pisanu A, Reccia I, Porceddu G et al (2012) Meta-analysis of prospective randomized studies comparing single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) and conventional multiport laparoscopic cholecystectomy (CMLC). J Gastrointest Surg 16(9):1790–1801

Chang SK, Wang YL, Shen L et al (2013) Interim report: a randomized controlled trial comparing postoperative pain in single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy and conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Asian J Endosc Surg 6(1):14–20

Pan MX, Jiang ZS, Cheng Y et al (2013) Single-incision vs three-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: prospective randomized study. World J Gastroenterol 19(3):394–398

Luna RA, Noqueira DB, Varela PS et al (2013) A prospective, randomized comparison of pain, inflammatory response, and short-term outcomes between single port and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 27(4):1254–1259

Madureira FA, Manso JE, Madureira FD et al (2013) Randomized clinical study for assessment of incision characteristics and pain associated with LESS versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 27(3):1009–1015

Sajid MS, Ladwa N, Kalra L et al (2012) Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg 36(11):2644–2653

Arezzo A, Scozzari G, Famiglietti F et al (2013) Is single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy safe? Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 27(7):2293–2304

Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ (1995) An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 180(1):101

Marks JM, Phillips MS, Tacchino R et al (2013) Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with improved cosmesis scoring at the cost of significantly higher hernia rates: 1-year results of a prospective randomized, multicenter, single-blinded trial of traditional multiport laparoscopic cholecystectomy vs single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 216(6):1037–1047

Acknowledgments

We also acknowledge the contributions of Dr Maria Mayasari, in the collection of data regarding our patients’ pre-operative status and intra-operative events.

Conflict of interest

This study is an investigator-initiated clinical trial. Covidien (Norwalk, USA) provided the SILS™ port, Autosuture Roticulator Endo Grasp™ and Autosuture Roticulator Endo Dissect™ for patients randomized to undergo single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Disclosures

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

www.ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01824186.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, S.K.Y., Wang, Y.L., Shen, L. et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Post-operative Pain in Single-Incision Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. World J Surg 39, 897–904 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2903-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2903-6