Abstract

Barriers to access and delivery of effective healthcare for autistic individuals have received attention in the social science literature. Less understood is why and how these barriers exist. The purpose of this qualitative review was to explore and interpret salient findings and characteristics of qualitative research that has examined the experiences of healthcare providers providing care to autistic individuals. A systematic information retrieval of electronic databases resulted in 15 qualitative research studies that met the inclusion criteria. Analysis of thematic findings and characteristics across studies was conducted, and a deeper interpretation highlighted an emphasis and reinforcement of the complexities of supporting autistic individuals in the healthcare context. Considerations are offered for diversifying and strengthening future research in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autistic individuals represent a unique population in the healthcare system and several studies have reported significant barriers faced by this population with regard to access and delivery of effective healthcare (Barber, 2017; Dern & Sappok, 2016; Nicolaidis et al., 2013; Vogan et al., 2017). Reported challenges have highlighted systematic gaps as well as issues of miscommunication, stigmatization, and marginalization created and reinforced through interactions with healthcare providers (Nicolaidis et al., 2015; Vogan et al., 2017). Autistic individuals have identified barriers including not knowing where to access support, feeling overwhelmed with steps required to access support, challenges in describing their needs, unmet service needs, and negative experiences with healthcare systems and providers (Vogan et al., 2017). Heterogeneity across the autistic spectrum means that one autistic person’s experience of their diagnosis is not representative of another’s and that autistic people have a variety of different needs (Masi et al., 2017; McCormick et al., 2020. For instance, autistic individuals with mental health and/or medical concerns have reported being significantly less satisfied with healthcare services than those without these additional needs (Vogan et al., 2017).

In a recent scoping review that documented themes across both quantitative and qualitative studies, Morris et al. (2019) noted recurring feedback from healthcare providers expressing that they lacked the knowledge and skills as well as training and support to effectively work with autistic individuals. In addition, healthcare providers expressed the need for better coordination and systematic changes at all levels of the healthcare system to better address the needs of autistic individuals. While this scoping review provided important insights about the experiences of healthcare providers, it was limited by methodology that focused on breadth of the issues, rather than depth. To address this gap, this current meta-synthesis review was conducted to explore in-depth the more salient themes across qualitative studies and deepen our understanding of the characteristics of this research to date in order to identify common and missing elements, potential biases and gaps, and opportunities to diversify and enhance future scholarship in this area.

This current systematic screen and meta-synthesis review of qualitative research studies explored the experiences of healthcare providers in their own words when working with autistic individuals. The current study had two primary objectives: (1) synthesize and interpret characteristics and underlying assumptions of qualitative research studies exploring the phenomenon “experiences of healthcare providers working with autistic individuals”, and (2) generate implications and recommendations for future qualitative research in this area.

Methods

Qualitative synthesis aims to aggregate, integrate, and interpret primary qualitative studies (Saini & Shlonsky, 2012). A meta-synthesis design was chosen for its foundation in integrative methods to create “taxonomies” (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007, p. 199) that synthesize themes across qualitative studies while providing opportunities to discover new interpretations of the phenomenon being studied. This methodological approach includes the synthesis of primary studies grounded in diverse qualitative methods and a range of findings (Saini & Shlonsky, 2012). The meta-synthesis approach was well-suited to the objectives of the current study, as it allowed for a rich interpretation of the experiences as articulated by healthcare providers working with autistic individuals.

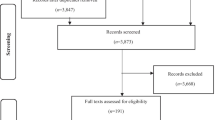

A broader scoping review of both quantitative and qualitative research (Morris et al., 2019) was conducted in April 2018. A systematic search of the research literature was completed utilizing four databases (Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Social Work Abstracts). Primary English-language research studies were included if they met two criteria: (1) participants were healthcare professionals working in a healthcare context directly with autistic individuals, and (2) primary focus was experiences providing care to autistic patients. The first search yielded a total of 1640 articles. Once duplicates were removed, 977 articles remained. Title and abstract screening resulted in 54 remaining articles and a full-text review resulted in 27 articles, 14 of which included qualitative methodologies.

For the current review, the 14 qualitative articles found through this initial systematic search and screen were included and in April 2020 an updated search and screen employing the same methodologies described above was conducted to include any qualitative research published since the scoping review. This second systematic search and screen produced one additional study, for a final sample of 15 articles (see Table 1).

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data extraction focused on key characteristics across studies including thematic findings, focus and emphasis of exploration, and theoretical and disciplinary positioning. In accordance with the meta-synthesis approach, a deeper critical analysis and interpretation of the qualitative data was conducted by all team members first individually and then together as a group. Of note, all of the researchers have professional healthcare research and practice experience either directly with or relevant to autistic individuals, which was an asset to a deeper understanding of the data. To mitigate potential researcher bias, investigator triangulation of analysis was conducted between all members of the research team (Carter et al., 2014), and member checking of preliminary findings with subject matter and methodological experts was facilitated through discussion at an international qualitative healthcare research conference (Morris & Greenblatt, 2019).

Results

Results highlight thematic findings and key characteristics across studies that represent provider experiences providing care to autistic patients. Through deeper interpretation of these findings and key characteristics, an emphasis on the complexity of autism was found to underlie and dominate research in this area to date.

Thematic Findings

Aligning with the findings of the broader scoping review, six key themes were noted by participants across the 15 studies as related to their experiences working alongside autistic patients in healthcare settings: complexity beyond usual role, limited knowledge and resources, training/prior experience, communication and collaboration, need for information and training, and need for care coordination and systemic changes (see also Morris et al., 2019). Providers across disciplines noted that autistic patients presented with a number of complex health and service needs that often went beyond the scope of the practitioners’ ability to address within the confines of their current role. Additionally, limitations in understanding what autism is, how it presents, how to effectively support and communicate/collaborate with autistic patients, and what external supports and resources may be available or beneficial precluded them from feeling confident in supporting this population in the patient-provider relationship and/or with navigating the system. Providers across studies identified a need for more information, training, coordination of care, and broader systemic changes to increase professional and system capacity to provide effective healthcare interventions and supports.

Key Characteristics of Studies

Study Aims and Focus of Inquiry

Of the 15 studies in this review, the majority explored autism knowledge, experiences, and healthcare provider needs (Morris et al., 2018; Daley & Sigman, 2002; Garg et al., 2014; Ghaderi & Watson, 2019; Muskat et al., 2015; Unigwe et al., 2017; Warfield et al., 2015; Zerbo et al., 2015; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). Four studies inquired about specific strategies or tools that providers were currently implementing or recommending for use when working with autistic patients (Fenikile et al., 2015; Halpin, 2016; Kuhlthau et al., 2015; Levy et al., 2016). Three studies focused inquiry of professional perceptions of patient and family needs in the healthcare system (Morris et al., 2018; Carbone et al., 2010; Trembath et al., 2016). Two studies also interviewed system users (Levy et al., 2016; Muskat et al., 2015).

Twelve studies explored experiences working specifically with children and youth and their families in care (Morris et al., 2018; Carbone et al., 2010; Daley & Sigman, 2002; Fenikile et al., 2015; Garg et al., 2014; Ghaderi & Watson, 2019; Halpin, 2016; Kuhlthau et al., 2015; Levy et al., 2016; Muskat et al., 2015; Trembath et al., 2016; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). Only one of these studies made mention of autistic adults, as the focus of inquiry was on the transition to adult care (Kuhlthau et al., 2015). Two studies specifically focused inquiry on participants’ experiences working with adults (Warfield et al., 2015; Zerbo et al., 2015), and one study inquired about experiences with autistic patients across the lifespan (Unigwe et al., 2017). None of the reviewed studies made reference to experiences or needs of older adults.

Many of the studies reviewed focused on barriers and challenges to service provision with this population, for example, “questions…addressed needs and barriers to screening and referral practices” (Fenikile et al., 2015), questions about “barriers to transition and improving the transition process” (Kuhlthau et al., 2015), and “probed about challenges of clinical care, impact on physicians schedule…” (Zerbo et al., 2015). None of the reviewed studies was as explicit in probing for positive experiences or facilitators to care. Two studies noted that their questions were designed to capture information about both barriers and facilitators, though in the description of overall aim or research questions both of these studies mentioned barriers but not facilitators (i.e., in-depth exploration of themes already found in the research of physician dissatisfaction with medical homes for autistic children) (Carbone et al., 2010); and “what challenges do HCPs in the ED face in providing care to children and youth with ASD?” (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). Neither of these studies provided a sample of specific questions used.

Nine studies did not share the specific questions used for data collection (Morris et al., 2018; Carbone et al., 2010; Fenikile et al., 2015; Garg et al., 2014; Halpin, 2016; Kuhlthau et al., 2015; Unigwe et al., 2017; Warfield et al., 2015; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). Notably, of these nine, two studies offered access to the interview guide: one as available upon request to the authors (Warfield et al., 2015), and the other indicated it was available in an appendix which was not added to the article nor found on the journal website (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). Four studies shared one question or a sample of questions, all using neutral and open-ended language (Daley & Sigman, 2002; Ghaderi & Watson, 2019; Muskat et al., 2015; Zerbo et al., 2015), for example, “what other comments do you have about your experiences with autism in India?” (Daley & Signman, 2002), and “what do you remember most about how the child experienced hospitalization?” (Muskat et al., 2015). Two studies shared the full set of questions used (Levy et al., 2016; Trembath et al., 2016), one also sharing sub-questions and probes (Levy et al., 2016).

An analysis of the language of the shared questions highlights some potential underlying assumptions about autistic patients as being particularly complex or challenging to work with, and/or requiring unique provider skills or accommodations in the care setting. For example, one question asked “what have you done (personally) to help make it more likely that families will follow through and adhere to treatment for ASD?” (Levy et al., 2016). A probe below this question asks “what were barriers that you saw to providing help ro support to the family?” but there is no similar probe asking about facilitators. Another example question “can you give me an example of a situation in which it’s either not possible or very difficult to help parents become informed about the treatments you are providing” (Trembath et al., 2016) was not preceded or followed by a request for an example of when informing about treatment went smoothly. While subtle, these types of questions may implicitly express the notion that autistic patients and their families may be less likely to listen to, understand, and/or follow through with treatment plans and that when treatment is not initiated or completed that it is due to something about the family rather than perhaps a systemic gap.

Six studies probed providers specifically about their knowledge, experience, and/or confidence in working with autistic patients prior to embarking on the qualitative data collection, which may have primed providers to think that this population requires a particular set of expertise in care and also to question whether or not they do have the knowledge, experience, or confidence to provide this care (Morris et al., 2018; Fenikile et al., 2015; Garg et al., 2014; Ghaderi & Watson, 2019; Unigwe et al., 2017; Zerbo et al., 2015).

Theoretical Frameworks

Of note, epistemological and theoretical underpinnings of the research design and analysis were not explicitly stated in 14 of the 15 reviewed studies. The study that did explicitly state this noted the use of critical reflective inquiry in their research design and analysis, a method deeply rooted in critical theory (Halpin, 2016). Four studies identified an intention to engage in an inductive process of theory development, involving a purposeful disengagement with theory prior to data collection to allow for a theoretical framework to emerge from a thematic analysis of the words of participants, although they did not go on to discuss theory generation after the results were presented (Morris et al., 2018; Fenikile et al., 2015; Levy et al., 2016; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). Additionally, almost all of the reviewed studies were conducted in Western cultural contexts (i.e., Australia, USA, UK, and Canada), with only one study conducted outside of these regions, in India (Daley & Sigman, 2002).

Researcher Discipline

Most of the studies reviewed did not provide information declaring the practice discipline of the researchers, but this was easily found through an Internet search. All but one of the reviewed studies (i.e., Ghaderi & Watson, 2019) involved a team of inter-professional researchers. The first authors were pediatricians in five studies (Carbone et al., 2010; Fenikile et al., 2015; Garg et al., 2014; Levy, et al., 2016; Zwaigenbaum, et al., 2016). The remaining nine first authors were from seven different disciplines: epidemiology (Zerbo et al., 2015), nursing (Halpin, 2016), primary care (Unigwe et al., 2017), psychology (Daley & Sigman, 2002, Ghaderi & Watson, 2019), social work (Morris et al., 2018; Muskat, et al., 2015), sociology/social policy (Kuhlthau et al., 2015; Warfield et al., 2015), and speech-language pathology (Trembath et al., 2016).

Participant Demographics

While the researchers were representative of diverse disciplinary backgrounds, the majority of participants represented medicine or nursing fields, and a number of healthcare disciplines were missing (i.e., occupational therapy, behavior therapy, etc.). Participants included primary care physicians (6 studies), “physicians” more broadly (4 studies), pediatricians (3 studies), psychiatrists (2 studies), nurses (6 studies), social work (4 studies), psychologists (3 studies), and speech-language pathologists (2 studies). Participants worked across a variety of practice settings, including hospital, community, and private practice settings (see Table 1). The majority of participants either only worked with children and youth in practice (10 studies) or were only asked about their work with children and youth (2 studies). Three studies also included autistic youth or parents of autistic children as participants. In Carbone et al. (2010), parent participants’ children were all male, between the ages of 4 and 14, and had diagnoses including PDD-NOS, autistic disorder, and Aspergers. In Levy et al. (2016), parent participants had children ages 2–5 with a parent-reported diagnosis of autism. In both of these studies, healthcare provider experiences shared were not limited to these particular cases. Muskat et al. (2015) also interviewed autistic youth (diagnosis confirmed by parent report and hospital records) and their parents, and was the only study that matched provider and parent participants so the analysis was specific to experiences across 20 cases of autistic youth (17 male, 3 female) aged 10–16. Several of the studies noted homogeneity across research participants and the limitations of this on the generalizability of their findings to a more diverse population of healthcare providers (Morris et al., 2018; Carbone et al., 2010; Daley & Sigman, 2002; Fenikile et al., 2015; Garg et al., 2014; Ghaderi & Watson, 2019; Kuhlthau et al., 2015; Muskat et al., 2015; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016).

Interpretation of Findings

When reviewing and engaging in a deeper interpretation of the thematic findings and key characteristics across studies, the researchers noted an underlying emphasis and reinforcement of the complexity of supporting autistic individuals in the healthcare context. In particular, an underlying theme undercutting all of the qualitative studies in this review is the notion that “autism” represents a uniquely complex presentation within the healthcare system, one that many healthcare providers perceive as requiring supports beyond those which they typically provide. Only one study addressed the ambiguity and heterogeneity of the word used to describe the population of which they were inquiring (Daley & Sigman, 2002), despite a highly documented understanding of autism as a spectrum diagnosis representing variable presentations across individuals (APA, 2013; Chaste et al., 2015; Georgiades et al., 2013). Providers across studies made reference to the notion that autistic individuals require a significant time commitment, during and between appointments (Carbone et al, 2010; Unigwe et al., 2017; Warfield et al., 2015; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). Physicians across studies noted that they would prefer to refer their autistic patients out to specialists who have deeper knowledge and more access to resources to provide supports relevant to autism (Carbone et al., 2010; Fenikile et al., 2015; Ghaderi & Watson, 2019; Levy et al., 2016; Unigwe et al., 2017). Additionally, in one study, pediatric hospital social workers reported limited knowledge of community resources and lack of clarity regarding the social work role when working with children with autism (Morris et al., 2018).

Discussion

The purpose of this qualitative review was to provide an in-depth analysis of the views of service providers by exploring both themes and methods across qualitative studies. The high frequency of themes related to limitations of care may rest on assumptions that autistic people represent a complexity that requires healthcare providers to work outside the capacity of their typical role, and that healthcare providers perceive limitations in their knowledge, skill, and resources to work with this population. While research questions typically aim to fill a gap in knowledge by purposely capturing information about barriers, it is worth considering the impact that language and/or implicit assumptions embedded in research design may have on participant responses; we wonder if research may be pre-emptively reinforcing a conceptualization of autism as a “complex” presentation that is expected to be met with challenges and barriers to service provision. While there are several reasons for not publically sharing an interview guide or specific questions asked in qualitative research, for example, the notion of “researcher as instrument” which means that questions may change from participant to participant based on the influence of both the participant and interviewer during the data collection phase (Galletta & Cross, 2013; Morse, 2012), the opportunity to critically analyze interview guides and questions asked may provide valuable information for future researchers to effectively fill relevant knowledge gaps. Some selection bias may occur when researchers choose to provide a description of questions asked or choose one or a few questions to share publically.

While there may be a number of factors contributing to the conceptualization of autism as being uniquely complex, such as the differences in diagnostic criteria and labelling since the diagnosis was first defined (Chamak, 2008; Chamak & Bonniau, 2013; Kanner, 1943; Leonard et al., 2010; Silverman, 2011; Verhoeff, 2013; Wolff, 2004); the high prevalence of co-occurring and/or overlapping psychiatric conditions (Gillberg et al., 2016; Marriage et al., 2009; Nylander et al., 2018; Perlman, 2000; Tsakanikos et al., 2007; Weiss et al., 2018); a lack of access to care coordination or community resources (Warfield et al., 2015); and the lack of autism-specific information provided to healthcare providers during their formal academic training (Bruder et al., 2012; Warfield et al., 2015; Zerbo et al., 2015), it is important for researchers and clinicians to consider the potential implications of this emerging conceptualization of autism.

When we ask healthcare professionals about their experiences working with autistic individuals, we may be reinforcing a conceptualization of autism as a homogenous diagnosis that people can speak to unilaterally. In reality, autism as a diagnostic label represents a spectrum of phenotypical presentation, and the diagnostic criteria have gone through several reiterations and changes over the years since it was first defined (Chamak, 2008; Chamak & Bonniau, 2013; Kanner, 1943; Leonard et al., 2010; Silverman, 2011; Verhoeff, 2013; Wolff, 2004). It could be argued that perhaps the reason why a theme of complexity has prevailed across the reports from healthcare providers in these studies is that they are speaking to a particular subset of the population of those diagnosed with autism, generally stereotyped as white Western male children with socioemotional and behavioral challenges (Pierce et al., 2014; Robertson et al., 2017). Perhaps the research has yet to effectively capture the experiences of healthcare providers working with adults, non-males, and/or people who are less significantly impacted by overt autism symptomatology (e.g., those who would have been diagnosed with Asperger syndrome under the DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994)).

The phenomenon of “healthcare providers’ experience working with autistic individuals” that has been presented across these qualitative studies has been generated within a homogenous cultural and geographically influenced research and practice context. This may be partially influenced by limiting the scope of the current analysis to manuscripts published in English, but is worthy of mentioning when considering the construction of this phenomenon and subsequent applicability to non-Western cultural contexts. Additionally, a number of healthcare disciplines have yet to be explicitly identified as targeted participants in qualitative studies examining healthcare practices with autistic patients, for example, occupational therapists, behavioral therapists, and spiritual care providers. As the findings from this review demonstrate, many physicians report a preference to refer individuals with autism to other specialties. It is critical to understand the experiences of these professionals which may be unique to the findings across studies to date, to get a better sense of healthcare experiences at this more specialized level and to ensure suitable and effective referrals. As was seen in some of the studies in this review, there is some benefit to be gained from purposive sampling of uni-disciplinary experiences as it may be that some disciplines have unique perspectives and/or strengths to bring forward to an interdisciplinary healthcare team in practice settings. When the researcher and participant have different assumptions about the nature of a phenomenon and assign different meanings to the questions being posed by researchers, we cannot be sure that participants are responding to questions as they were intended to be asked (Qu & Dumay, 2011; Valsiner, 2000).

Many of the studies in this review used open-ended survey or interview questions to gather qualitative data. As with all qualitative research, factors such as environmental context, cultural influences, the complex relationship between “knowing” or “feeling” and then putting this into words to be understood by another, and non-verbal communication methods may influence participant selection, data collection, or analysis of information (Affleck et al., 2012; Hollway and Jefferson, 2013; Kvale & Brinkman, 2009; Lihong & Nunes-Miguel, 2013; McKee et al., 2013). It is surprising that although the studies included in this review were all exploring the topic of autism, which is defined by challenges or differences in socio-emotional communication (DSM-5; APA, 2013), the limitations of interviews as a specific and narrow form of communication were not discussed.

The absence of theoretical discussion in the reviewed studies is consistent with traditional healthcare research, in which theory is rarely described in-depth (Alise & Teddlie, 2010; Bunniss & Kelly, 2010). When theoretical and epistemological bases are not well-understood or identified in research, however, there may be some risk of discordance between what the researchers intend to do and the way they design and carry out their project (Adams St. Pierre, 2016; Bunniss & Kelly, 2010; Fadyl & Nicholls, 2013). The fact that providers note that autistic people represent a complexity requiring more support, knowledge, skill, communication, collaboration, and care coordination may have emerged as a result of the focus of inquiry being mostly on the individual practices of healthcare providers. In Western cultural contexts, individuality is often prioritized over collectivism, and this may influence healthcare providers’ professional sense of individual responsibility for all aspects of patient care. An absence of identification of theoretical influence may mean that studies to date do not recognize ways that individualistic culture may place immense pressure on providers resulting in fears that they are unable to effectively provide care.

Many critics have raised concern about qualitative research re-constructing itself in attempt to align itself with quantitative research discourses, subsequently losing sight of the broader values and paradigms that originally fostered these approaches (Barbour, 2001; Flick, 2017; Gilgun, 2005; Wainright, 1997). This may influence researchers to adopt a superficial utilization of language that may be inconsistent and incompatible with their actual research process in order to access funding, be published, and be heard (Adams St. Pierre, 2016; Barbour, 2001; Denzin, 2009; Fadyl & Nicholls, 2013; Morse, 2012; Sandelowski & Leeman, 2012; van Wijngaarden et al., 2017; Wainright, 1997). For example, despite generalizability and quantification of sample size being well-known contentions in qualitative research, they were still both reported as a limitation across many studies in this review. It is possible that the dominance of quantitative research in healthcare has generated bureaucratic expectations to report sample size and generalizability as limitations of qualitative research order to be approved for publication, even when generalizability is not typically a goal of qualitative research (Boddy, 2016; Morse, 2012; van Wijngaarden et al., 2017). There may be value in researchers continuing to critically examine the concept of “rigour” in qualitative research, and seek to address the discordance in how it has been applied across the healthcare research literature (Barbour, 2001; Mays & Pope, 1995; Morse, 2015; van Wijngaarden et al., 2017; Ward-Schofield, 1993).

Limitations

This study narrowly focused on qualitative research that was conducted with healthcare providers as participants. As this study explored a small sample of research, including only 15 studies, it is expected that there will be a higher number of common characteristics than would be found with a larger sample size. It is possible that as more research in this area develops, heterogeneity across characteristics of studies will naturally expand beyond the themes currently noted.

Considerations for Future Research

The study provides areas for consideration as well as implications for future research utilizing qualitative methodology to explore service provision and autism in the healthcare setting. As research to date has captured a number of challenges and gaps related to healthcare service provision with autistic individuals, it may be an opportune time for future researchers to use a strength-based research framework to explore provider and patient strengths, and facilitators of care in healthcare service provision with this population. Additionally, future research may consider alternative and less stigmatizing and deficit-oriented perspectives on autism such as the neurodiversity movement, which shifts the definition of autism to representing difference in thinking, processing, communicating, and behaving (Grinker, 2010; Krcek, 2013). Researchers should consider taking time to reflect closely and critically on an analysis of their own assumptions and biases when it comes to autism and pay attention to the ways in which the language used to frame research questions, interview guides, and data collection questions may reinforce stigmatizing and dehumanizing stereotypes of autistic people (Botha et al., 2021). For example, purposeful attention should be given to ways that language may subtly reinforce underlying assumptions of autistic people as complex, as disordered, as treatment resistant, or as requiring specialist-level provider knowledge or skills. When considering the use of language in research, equally as important as critical self-reflection is the inclusion of autistic scholars as co-researchers and consultants on research projects (Botha et al., 2021; Nicolaidis et al., 2019). These paradigm shifts may unearth new information as shared by clinicians working alongside this population in healthcare settings, which could significantly contribute to enhancing discussions around best-practice initiatives across healthcare settings.

Research may be enhanced by continued attention to diversity across culture, race, language, and healthcare discipline. Additionally, a purposeful exploration of experiences of providers working with specific subsets of those on the autism spectrum including adults, seniors, non-males, non-whites, non-Western, and/or people whose autism is less overt would contribute to a gap in the current research context. Autistic individuals and their families and communities are an extremely important source of qualitative knowledge for service providers and researchers in the area of healthcare, and research that incorporates these experiences should be included in any discussion of healthcare practice initiatives. Research with autistic individuals should also be examined to highlight potential gaps in knowledge or assumptions that may be impacting thematic outcomes across studies.

It may be of benefit for researchers to develop and communicate an understanding and awareness of how theory, context, epistemology, and assumptions may influence and frame their research about autism. Specifically, future research in this area should explore what the label of “autism” entails to both researchers and providers (Verhoeff, 2012).

Conclusion

This qualitative review shared an analysis and interpretation of themes and characteristics of qualitative research exploring the experiences of healthcare providers working alongside autistic patients in healthcare settings. The themes and key characteristics found across qualitative research in this area to date were critically interpreted, highlighting an emphasis and reinforcement of autism as a particularly complex diagnostic profile requiring high demands on healthcare providers to effectively support autistic individuals in the healthcare context. This interpretation draws attention to the potential benefits of having a deep understanding of the ideas that may underlie or influence research to date on a phenomenon of interest. An awareness of the deeper influences on research design may serve not only to enhance the rigour and quality of future projects but also to make salient underlying assumptions of knowledge that may serve to further marginalize minority populations. The results of this review highlight opportunities for diversifying and strengthening future research and analysis in this area, in order to contribute uniquely to the field and further the generation of healthcare best practice initiatives with autistic individuals.

References

Adams St. Pierre, E. (2016). The long reach of logical positivism/logical empiricism. In N.K. Denzin & M.D. Giardina (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry through a critical lens (pp. 27–38). Routledge.

Affleck, W., Glass, K. C., & Macdonald, M. E. (2012). The limitations of language: Male participants, stoicism, and the qualitative research interview. American Journal of Men’s Health, 7(2), 155–162.

Alise, M. A., & Teddlie, C. (2010). A continuation of the paradigm wars? Prevalence rates of methodological approaches across the social/behavioral sciences. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(2), 103–126.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Press.

Barber, C. (2017). Meeting the healthcare needs of adults on the autism spectrum. British Journal of Nursing, 26(7), 420–425.

Barbour, R. S. (2001). Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ, 322(7294), 1115–1117.

Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 19(4), 426–432.

Botha, M., Hanlon, J., & Williams, G.L. (2021). Does language matter? Identity-first versus person-first language use in autism research: A response to Vivanti. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04858

Bruder, M. B., Kerins, G., Mazzarella, C., Sims, J., & Stein, N. (2012). Brief report: The medical care of adults with autism spectrum disorders: Identifying the needs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(11), 2498–2504.

Bunnis, S., & Kelly, D. R. (2010). Research paradigms in medical education research. Medical Education, 44, 358–366.

Carbone, P. S., Behl, D. D., Azor, V., & Murphy, N. A. (2010). The medical home for children with autism spectrum disorders: Parent and pediatrician perspectives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(3), 317–324.

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547.

Chamak, B. (2008). Autism and social movements: French parents’ associations and international autistic individuals’ organizations. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30(1), 76–96.

Chamak, B., & Bonniau, B. (2013). Changes in the diagnosis of autism: How parents and professionals act and react in France. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 37(3), 405–426.

Chaste, P., Klei, L., Sanders, S.J., Hus, V., Murtha, M.T., Lowe, J.K.,…& Devlin, B. (2015). A genome-wide association study of autism using the simons simplex collection: Does reducing phenotypic heterogeneity in autism increase genetic homogeneity? Biological Psychiatry, 77, 775-784

Daley, T. C., & Sigman, M. D. (2002). Diagnostic conceptualization of autism among Indian psychiatrists, psychologists, and pediatricians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(1), 13–23.

Denzin, N. K. (2009). Qualitative inquiry under fire: Toward a new paradigm dialogue. Routledge.

Dern, S., & Sappok, T. (2016). Barriers to healthcare for people on the autism spectrum. Advances in Autism, 2(1), 2–11.

Fadyl, J. K., & Nicholls, D. A. (2013). Foucault, the subject and the research interview: A critique of methods. Nursing Inquiry, 20(1), 23–29.

Fenikile, T. S., Ellerbeck, K., Filippi, M. K., & Daley, C. M. (2015). Barriers to autism screening in family medicine practice: A qualitative study. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 16(4), 356–366.

Flick, U. (2017). Challenges for a new critical qualitative inquiry: Introduction to the special issue. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 3–7.

Galletta, A., & Cross, W. E. (2013). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research design to analysis. NYU Press.

Garg, P., Lillystone, D., Dossetor, D., Kefford, C., & Chong, S. (2014). An exploratory survey for understanding perceptions, knowledge, and educational needs of general practitioners regarding autistic disorders in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 8(7), PC01–PC09.

Georgiades, S., Szatmari, P., & Boyle, M. (2013). Importance of studying heterogeneity in autism. Neuropsychiatry, 3(2), 123–125.

Ghaderi, G., & Watson, S. L. (2019). “In medical school, you get far more training on medical stuff than developmental stuff”: Perspectives on ASD from Ontario physicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 683–691.

Gilgun, J. F. (2005). “Grab” and good science: Writing up the results of qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 15(2), 256–262.

Gillberg, I. C., Helles, A., Billstedt, E., & Gillberg, C. (2016). Boys with Asperger syndrome grow up: Psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders 20 years after initial diagnosis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 74–82.

Grinker, R. R. (2010). Commentary: On being autistic, and social. Ethos: Journal of the Society for Psychological Anthropology, 38(1), 172–178.

Halpin, J. (2016). What do nurses think they are doing in pre-school autism assessment. British Journal of Nursing, 25(6), 319–323.

Hollway, W., & Jefferson, T. (2013). Introduction: The need to do research differently. In W. Hollway & T. Jefferson (Eds.), Doing qualitative research differently: A psychosocial approach (2nd ed., pp. 1–5). Sage Publications.

Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217–250.

Krcek, T. E. (2013). Deconstructing disability and neurodiversity: Controversial issues for autism and implications for social work. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 24(1), 4–22.

Kuhlthau, K. A., Warfield, M. E., Hurson, J., Delahaye, J., & Crossman, M. K. (2015). Pediatric provider’s perspectives on the transition to adult health care for youth with autism spectrum disorder: Current strategies and promising new directions. Autism, 19(3), 262–271.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Sage Publications.

Leonard, H., Dixon, G., Whitehouse, A. J. O., Bourke, J., Aiberti, K., & Nassar, N.,…& Glasson, E.J. . (2010). Unpacking the complex nature of the autism epidemic. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(4), 548–554.

Levy, S. E., Frasso, R., Colantonio, S., Reed, H., Stein, G., & Barg, F.K.,…& Fiks, A.G. . (2016). Shared decision making and treatment decisions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Academic Pediatrics, 16(6), 571–578.

Lihong, Z., & Nunes Miguel, B. (2013). Doing qualitative research in Chinese contexts: Lessons learned from conducting interviews in a Chinese healthcare environment. Library Hi Tech, 31(3), 419–434.

Marriage, S., Wolverton, A., & Marriage, K. (2009). Autism spectrum disorder grown up: A chart review of adult functioning. Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 18(4), 322–328.

Masi, A., DeMayo, M. M., Glozier, N., & Guastella, A. J. (2017). An overview of autism spectrum disorder, heterogeneity, and treatment options. Neuroscience Bulletin, 33(2), 183–193.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (1995). Rigour in qualitative research. BMJ, 311, 109–112.

McCormick, C.E.B., Kavanaugh, B.C., Sipsock, D., Righi, G., Oberman, L.M., De Luca D.M., Uzun, E.D.G., Best, C.R., Jerskey, B.A., Quinn, J.G., Jewel, S.B., Wu, P., McLean, R.L., Levine, T.P., Tokadjian, H., Perkins, K.A., Clarke, E.B., Dunn, B., Gerber, A.H.,…& Morrow, E.M. (2020). Autism heterogeneity in a densely sampled U.S. population: Results from the first 1,000 participants in the RI-CART study. Autism Research, 13(3), 474–488.

McKee, M., Schlehofer, D., & Thew, D. (2013). Ethical issues in conducting research with deaf populations. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2174–2178.

Morris, R., & Greenblatt, A. (2019). Healthcare provider experiences with autism: A review and synthesis of qualitative research studies [abstract]. In: Abstracts, Poster Presentation, Qualitative Health Research Conference, 2018. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918819364

Morris, R., Muskat, B., & Greenblatt, A. (2018). Working with children with autism and their families: Pediatric social worker perceptions of family needs and the role of social work. Social Work in Health Care, 57(7), 483–501

Morris, R., Greenblatt, A., & Saini, M. (2019). Healthcare providers’ experiences with autism: A scoping review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(6), 2374–2388

Morse, J. M. (2012). Qualitative health research: Creating a new discipline. Routledge.

Morse, J. M. (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222.

Muskat, B., Burnham Riosa, P., Nicholas, D. B., Roberts, W., Stoddart, K. P., & Zwaigenbaum, L. (2015). Autism comes to the hospital: The experiences of patients with autism spectrum disorder, their parents and health-care providers at two Canadian paediatric hospitals. Autism, 19(4), 482–490.

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D.M., Ashkenazy, E., McDonald, K.E., Dern, S., Baggs, A.E.V.,…& Boisclair, W.C. (2015). “Respect the way I need to communicate with you”: Healthcare experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 19(7), 824-831

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., Kapp, S.K., Baggs, A., Ashkenazy, E., McDonald, K.,…& Joyce, A. (2019). AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism, 23(8), 2007-2019

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., McDonald, K., Dern, S., Boisclair, W. C., Ashkenazy, E., & Baggs, A. (2013). Comparison of healthcare experiences in autistic and non-autistic adults: A cross-sectional online survey facilitated by an academic-community partnership. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(6), 761–769.

Nylander, L., Axmon, A., Bjorne, P., Ahlstrom, G., & Gillberg, C. (2018). Older adults with autism spectrum disorders in Sweden: A register study of diagnoses, psychiatric care utilization and psychotropic medication of 601 individuals. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(9), 3076–3085.

Perlman, L. (2000). Adults with Asperger disorder misdiagnosed as schizophrenic. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31(2), 221–225.

Pierce, N. P., O’Reilly, M. F., Sorrells, A. M., Fragale, C. L., White, P. J., Aguilar, J. M., & Cole, H. A. (2014). Ethnicity reporting practices for empirical research in three autism-related journals. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1507–1519.

Robertson, R. E., Sobeck, E. E., Wynkoop, K., & Schwartz, R. (2017). Participant diversity in special education research: Parent-implemented behaviour interventions for children with autism. Remedial and Special Education, 38(5), 259–271.

Qu, S. Q., & Dumay, J. (2011). The qualitative research interview. Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management, 8(3), 238–264.

Saini, M., & Shlonsky, A. (2012). Systematic synthesis of qualitative research. Oxford University Press.

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2007). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer Publishing Co.

Sandelowski, M., & Leeman, J. (2012). Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1404–1413.

Silverman, C. (2011). Understanding autism: Parents, doctors, and the history of a disorder. Princeton University Press.

Trembath, D., Hawtree, R., Arciuli, J., & Caithness, T. (2016). What do speech-language pathologists think parents expect when treating their children with autism spectrum disorder? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18(3), 250–258.

Tsakanikos, E., Sturmey, P., Costello, H., Holt, G., & Bouras, N. (2007). Referral trends in mental health services for adults with intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 11(1), 9–17.

Unigwe, S., Buckley, C., Crane, L., Kenny, L., Remington, A., & Pellicano, E. (2017). GPs confidence in caring for their patients on the autism spectrum: An online self-report study. British Journal of General Practice, 67(659), e445–e452.

Valsiner, J. (2000). Data as representations: Contextualizing qualitative and quantitative research strategies. Social Science Information, 39(1), 99–113.

Van Wijngaarden, E., van der Meide, H., & Dahlberg, K. (2017). Researching health care as a meaningful practice: Toward a nondualistic view on evidence for qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 27(11), 1738–1747.

Verhoeff, B. (2012). What is this thing called autism? A critical analysis of the tenacious search for autism’s essence. BioSocieties, 7(4), 410–432.

Verhoeff, B. (2013). Autism in flux: A history of the concept form Leo Kanner to DSM-5. History of Psychiatry, 24(4), 442–458.

Vogan, V., Lake, J. K., Tint, A., Weiss, J. A., & Lunsky, Y. (2017). Tracking health care service use and the experiences of adults with autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability: A longitudinal study of service rates, barriers, and satisfaction. Disability and Health Journal, 10(2), 264–270.

Wainright, D. (1997). Can sociological research be qualitative, critical, and valid? The Qualitative Report, 3(2), 1–17.

Ward-Schofield, J. (1993). Increasing the generalizability of qualitative research. In M. Hammersley (Ed.), Social research: Philosophy, politics, and practice (pp. 220–225). Open University/Sage.

Warfield, M. E., Crossman, M. K., Delahaye, J., Der Weerd, E., & Kuhlthau, K. A. (2015). Physician perspectives on providing primary medical care to adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 2209–2217.

Weiss, J. A., Isaacs, B., Diepstra, H., Wilton, A. S., Brown, H. K., McGarry, C., & Lunsky, Y. (2018). Health concerns and health service utilization in a population cohort of young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(1), 36–44.

Wolff, S. (2004). The history of autism. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 13(4), 201–208.

Zerbo, O., Massolo, M. L., Qian, Y., & Croen, L. A. (2015). A study of physician knowledge and experience with autism in adults in a large integrated healthcare system. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(12), 4002–2014.

Zwaigenbaum, L., Nicholas, D.B., Muskat, B., Kilmer, C., Newton, A.S., Craig, W.R.,…Sharon, R. (2016). Perspectives of health care providers regarding emergency department care of children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(5), 1725-1736

Funding

Funding was received through a UBC Institute of Mental Health Marshall Scholar Award and a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Doctoral Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morris, R., Greenblatt, A. & Saini, M. Working Beyond Capacity: a Qualitative Review of Research on Healthcare Providers’ Experiences with Autistic Individuals. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 10, 158–168 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00283-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00283-6