Abstract

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), an 8-week group psychosocial intervention, has received increasing research support for its efficacy in oncology settings. Changes associated with MBSR participation for people with cancer include improved psychological functioning and quality of life. However, as with other populations, it remains unclear which components of MBSR bring about change and whether targeted constructs are critical in changing outcomes. We propose a mediation model to be tested as a first step towards understanding program mechanisms. Specifically, changes in mindfulness and rumination were hypothesized to mediate the impact of MBSR participation on symptoms of depression in people living with cancer. A waitlist-controlled study of MBSR participation in 77 women who had completed cancer treatment was conducted to test this model. Pre- to post-program, MBSR participants improved significantly more on depressive symptoms and mindfulness and decreased more on rumination scores compared to waiting controls. Decreases in rumination mediated the impact of MBSR on depressive symptoms, but mindfulness scores did not. Methodological recommendations are presented to promote research that will further elucidate the mechanisms of action of MBSR. Mediation analyses will inform the next generation of randomized controlled trials and may lead to program modifications that will maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of mindfulness-based interventions in cancer settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to recent cancer prevalence and survival statistics, over six million women in the USA are cancer survivors. Breast cancer, the most common type of cancer among women, has an overall 5-year relative survival rate of 89.1% (Horner et al. 2009). Despite increasingly high survival rates, clinically significant physical and psychosocial effects often accompany a cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment (Adler et al. 2008; Bower 2008). For cancer patients, psychological symptoms including anxiety, depression (Kim et al. 2005; Verhoef et al. 2002), fatigue (Amato et al. 1998), and sleep problems (Dimeo et al. 1996) are common. Moreover, many cancer patients continue to have high levels of distress requiring psychosocial care following completion of primary treatments (Amato et al. 1998). Adjustment to stress involves psychological and behavioral coping responses, such as thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in response to receiving a cancer diagnosis that may influence mental health (e.g., Vickers 1996) and the severity of cancer-related symptoms (e.g., Yano et al. 2000). The potential benefits of psychosocial interventions designed to enhance coping with stress and improve quality of life may be substantial for cancer survivors.

Mindfulness and Cancer

Mindfulness meditation, a technique involving moment-to-moment nonjudgmental awareness of internal and external experience, is increasingly being applied as a stress reduction tool to improve symptoms associated with both psychological disorders and medical illnesses, including cancer (Baer 2003). Within a framework of nonjudging, acceptance, and patience, participants are taught to focus attention on the breath, body sensations, and eventually any objects (e.g., thoughts, feelings) that enter the field of awareness. Accelerated interest in the potential health benefits of mindfulness meditation has resulted in the development and widespread application of the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program of Jon Kabat-Zinn (1990), developed at the Stress Reduction Clinic of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center (Kabat-Zinn 1990). MBSR is a group intervention consisting of mindfulness meditation and gentle yoga that is designed to have applications for stress, pain, and illness (Kabat-Zinn 1990). The program is perceived as qualitatively distinct from other forms of meditation such as mantra-based practices and is not aimed at achieving a state of relaxation; rather, it targets the cultivation of insight and understanding of self and self-in-relationship via the practice of mindfulness (Kramer et al. 1997). Mindfulness meditation as taught in the MBSR program is formally practiced while seated, walking, or lying down, and individuals are also taught to practice mindfulness “informally” when engaged in everyday activities.

In oncology settings, MBSR has been evaluated across psychological, behavioral, and biological dimensions. Several literature reviews have been conducted on the topic of MBSR in cancer settings (Carlson et al. 2009; Lamanque and Daneault 2006; Ledesma and Kumano 2009; Mackenzie et al. 2005; Matchim and Armer 2007; Ott et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2005). Overall, results from both controlled and uncontrolled studies show MBSR participation to be associated with diminished medical and psychological symptoms, including fatigue, mood disturbance, depression, anxiety, fear of recurrence, pain, and symptoms of stress (Carlson et al. 2001, 2003, 2004, 2007; Carlson and Garland 2005; Dobkin 2008; Garland et al. 2007; Speca et al. 2000; Van Wielingen et al. 2007). Participation in MBSR has also been associated with enhanced sleep quality and duration, post-traumatic growth, spirituality, energy, and quality of life among cancer patients (Carlson et al. 2003, 2004; Carlson and Garland 2005; Carmody and Baer 2008; Garland et al. 2007; Lengacher et al. 2009; Mackenzie et al. 2007; Spahn et al. 2003; Witek-Janusek et al. 2008). Thus, MBSR is a clinically valuable intervention for cancer patients who are undergoing or have completed primary treatments (Vickers et al. 2004; Vickers 2004).

Mechanisms of Mindfulness

Despite the bulk of evidence supporting its efficacy, it is not yet known what program elements bring about change for cancer patients and whether targeted constructs such as the cultivation of mindfulness are critical in changing outcomes. Addressing the question of “how” an intervention brings about change is achieved through an evaluation of mechanisms, defined as causal links between treatment and outcome (Watson et al. 1999). Uncovering mechanisms is an iterative process, whereby possible mediators are first identified on the basis of theory. A mediator is an intermediate variable that transmits the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable. A temporal relation is implied in that the independent variable (in this case, participating in MBSR or not) occurs before the mediating variable, which occurs before the dependent variable (MacKinnon 2008). The proposed mediators are first explored in hypothesis-generating analyses, and then they are validated through hypothesis testing analyses in the next generation of randomized controlled trials (e.g., using component control or additive designs to isolate specific causal mechanisms). Mediation analyses are an important first step toward ascertaining program mechanisms (Watson et al. 1999). Tests of mediation may help determine whether program components need to be modified and whether targeted constructs were critical in changing outcomes; tailoring programs accordingly can render such programs more effective and efficient (Wonderling et al. 2004).

Clinical researchers from many fields, including psychosocial oncology, have emphasized the importance of understanding how interventions work in order to advance treatment research (e.g., Kraemer et al. 2002; Temoshok and Wald 2002; Wetzel 1989; White and Ernst 2003, 2004). We must seek to understand change processes in order to prevent merely compiling a catalog of instances in which interventions do or do not work. Moreover, when findings from different trials are equivocal, an analysis of mediating variables informs interpretation of results (Temoshok and Wald 2002).

Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation

In developing hypotheses regarding mediators of MBSR, increased mindfulness and enhanced emotion regulation emerge prominently from the mindfulness-based intervention literature as likely candidates (Chambers et al. 2009; Epstein 1995; Germer 2005; Shapiro and Carlson 2009). Becoming more “mindful” may increase the tendency to directly experience emotion (versus avoiding emotion through perseverative thinking) and then respond adaptively to the environment, resulting in diminished psychological symptoms (Bredart et al. 1998; Kash et al. 1992; Keller 2000; Shapiro et al. 2006). Observing thoughts and emotions without attachment or judgment is hypothesized to increase emotional acceptance (Hopwood 1997; Hopwood et al. 1998; Lerman and Schwartz 1993), willingness to tolerate uncomfortable emotions and sensations (Lerman et al. 1993, 1995), and decrease reactivity to and time needed to recover from negative emotional experiences (Bishop et al. 2004; Kabat-Zinn 1990).

The second hypothesized mediator, rumination, is conceptualized as a measure of emotion regulation. Emotion regulation refers to the process of modulating aspects of an emotional experience or response and is viewed as central to mental health and adaptive functioning (Chambers et al. 2009; Gross 1998). Shapiro et al. (2006, 2008) have highlighted self-regulation and self-management as a mechanism that may explain how the mindfulness practice affects well-being (Shapiro and Carlson 2009; Shapiro et al. 2006). Specifically, the authors postulate that decreasing identification with emotions and thoughts as true or real, thereby enhancing the ability to see them merely as passing events in the mind, is associated with a lower likelihood of sustaining unhelpful automatic responses and habitual reactive patterns of behavior. Thus, emotional states such as anxiety or fear can be used as information, resulting in the capacity to choose to self-regulate in ways that foster greater well-being (Baer 2003; Bonadona et al. 2002; Chambers et al. 2009; Hopwood 1997; Shapiro and Carlson 2009; Watanabe and Bruera 1996). Rumination is defined as the tendency towards neurotic self-attentiveness and repetitive, recurrent, primarily past-oriented thinking about the self prompted by threats, losses, or perceived injustices (Trapnell and Campbell 1999). It is often a habitual mode of thinking which typically results in depressed mood that can be difficult to alleviate or regulate. If mindfulness practice allows people to become aware of this dysfunctional pattern and intentionally stops the downward spiral of rumination which leads to depression, decreases in rumination may be a potential mechanism of change through such regulation of emotion. In sum, the MBSR program may allow for exploration and increased tolerance of a broad range of thoughts, emotions, and sensations, which may reduce psychological symptoms associated with mental and physical health conditions (Fig. 1).

Mediators of MBSR

Previous research on mediators of change in outcomes in MBSR programs has most consistently targeted improvements in mindfulness, but a range of other potential mediators have also been addressed. Some of these have been based on proposed theories of the mechanisms of action of MBSR, including but not limited to emotion regulation. Consistent with the notion that benefits of the MBSR program in people with cancer is associated with increased mindfulness, results of several studies have shown that changes in scores on mindfulness scales mediate the association between meditation practice and well-being (Baer et al. 2008; Carmody and Baer 2008; Carmody et al. 2009; Lau et al. 2006). Nyklicek and Kuijpers (2008) also reported that increases in mindfulness mediated the impact of MBSR on vital exhaustion, perceived stress, and quality of life in a randomized waitlist-controlled study of individuals with symptoms of distress drawn from a community sample (Nyklicek and Kuijpers 2008). Shapiro et al. (2008) randomized a sample of college students to either MBSR, an Eight-Point Program (EPP) meditation intervention in which participants focused attention upon an inspirational passage, or a waitlist-control group. Mindfulness increased over time in the MBSR group relative to the EPP and control groups and increases in mindfulness mediated reductions in both rumination and levels of perceived stress (Shapiro et al. 2008). Finally, in the most extensive test of a mediation model in the context of MBSR that looked not only at mindfulness but also other theoretically relevant mediators, questionnaires were administered pre- and post-MBSR to a large number of individuals with a variety of medical and psychological concerns (Carmody et al. 2009). Proposed mediators of MBSR as suggested by Shapiro and Carlson (2009), specifically, values clarification (i.e., recognition of what is meaningful in life) and cognitive, emotional, and behavioral flexibility (i.e., adaptive and flexible responding to the environment) mediated the association between a mindfulness variable and psychological symptom reduction, but self-regulation of emotions and thoughts did not. In summary, existing research supports the hypothesis that increased levels of mindfulness mediate positive outcomes of MBSR, but the one test of the mediating role of emotion regulation mechanisms did not find a mediating relationship.

Mediators of MBSR in Cancer

To our knowledge, no published studies have tested for mediators of MBSR in a cancer patient population. The objectives of the current study were to confirm the previously observed benefit of MBSR of decreasing depressive symptoms in women with cancer and to test the potential mediating roles of increases in mindfulness and decreases in rumination on this effect. We hypothesized that participation in MBSR would be associated with reduced depressive symptoms and rumination and increased mindfulness. In addition, we expected that increased mindfulness and decreased rumination would mediate the impact of the program on depressive symptoms (Fig. 2).

Methods

Participants

Patients were recruited from the waitlist for the MBSR program offered through the Tom Baker Cancer Centre, in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. This program is offered to patients as part of the regular clinical treatment process. Patients were referred to the program by medical staff or self-referred via posted advertisements. They were recruited for the control group if there were more than 8 weeks before the start of the next MBSR program and the treatment group if there were fewer than 8 weeks before the next program. Medical/psychiatric conditions and medications were assessed during the initial telephone screening process and were confirmed with the patient at the first testing session. Patients were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria: (1) female; (2) age 18 years or older; (3) a diagnosis of cancer; and (4) completed all treatments except adjuvant therapy (e.g., tamoxifen). Exclusion criteria included: (1) current treatment with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or surgery within the past month; (2) recent change in medication (i.e., in the 2 weeks prior to the first testing session) or a planned change in medication during the 8-week study period; and (3) past participants in an MBSR group. All participants provided informed consent, and the study was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary.

Data Collection

Data collection began in May 2005 and included ten consecutive 8-week MBSR programs and ten “waiting periods” between programs over a 3-year period. Participants attended two assessment sessions, during the 2 weeks prior to the start of the MBSR program (or the 8-week waiting period) and during the 2 weeks after completion of the program (or end of the waiting period). Participants completed questionnaires at both assessment sessions.

Intervention

The MBSR intervention was modeled on the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program developed at the Massachusetts Medical Centre (Kabat-Zinn 1982, 1990) and since modified by Carlson and Speca (2010). The program is currently referred to as Mindfulness-Based Cancer Recovery. A comprehensive description of the program has been provided elsewhere (Carlson et al. 2009; Carlson and Speca 2010; Speca et al. 2000, 2006). Briefly, this 8-week group intervention consists of mindfulness meditation and gentle yoga and provides instruction on how to become aware of one’s personal responses to stress and to learn and practice techniques that will bring about healthier stress responses (Carlson et al. 2003). The program consists of weekly group sessions of 90 min each plus a 6-h retreat between weeks 6 and 7. Participants are encouraged to practice the meditation and yoga techniques at home for 45 min/day. CDs containing guided meditations and yoga sequences are provided to support home practice. CD descriptions and ordering information is available online at: www.mindfulnesscalgary.ca.

Measures

Demographic Information and Medical History Questionnaire

Demographic and medical information (i.e., date of birth, marital status, education level, hours of employment, ethnicity, current medications, cancer type and stage, and date of cancer diagnosis and treatment completion) was obtained via a demographics questionnaire designed for this study.

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Inventory—10 (Andresen et al. 1994)

Depressive symptomatology was assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Inventory—10 (CESD-10). This 10-item screening questionnaire is a short version of the original 20-item CES-D (Radloff 1977) that has been used extensively in general and chronic illness populations. The CESD-10 uses a four-point Likert scale (range 0 to 30) with higher scores representing greater depressive symptoms. A score ≥10 represents significant depressive symptoms (Andresen et al. 1994). The scale has shown good predictive accuracy when compared to the full-length version (Andresen et al. 1994; Cheng and Chan 2005), internal consistency (0.78) (Boey 1999), and convergent validity (Andresen et al. 1994).

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (Brown and Ryan 2003)

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) was developed to measure “present-centered attention-awareness”; that is, the presence or absence of attention to and awareness of what is occurring in the present. Participants were asked to rate the frequency of their experiences on a five-point rating scale (e.g., “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present”). A thorough validation process has demonstrated the reliability and validity of the MAAS for use in both college student and general adult populations (Brown and Ryan 2003), as well as in cancer patients (Carlson and Brown 2005).

Rumination–Reflection Questionnaire—Rumination subscale (Trapnell and Campbell 1999)

The Rumination subscale of the RRQ assesses a neurotic self-attentiveness (i.e., recurrent, primarily past-oriented thinking about the self), which is prompted by threats, losses, or injustices to the self. Participants rate their level of agreement or disagreement on a five-point rating scale (e.g., “I always seem to be rehashing in my mind recent things I’ve said or done”). There is evidence of good internal consistency (.90) and stability over a 10-month period and convergent validity (Brown and Ryan 2003; Teasdale and Green 2004; Trapnell and Campbell 1999).

Meditation Log

For the duration of the program, participants completed meditation logs on which they recorded the number of minutes spent practicing meditation and yoga each day. Participants handed in their meditation logs at the second testing session.

Data Analysis

Preliminary Analyses

All data analyses were carried out using SPSS for Windows version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Because participants were not randomly assigned to conditions, to ensure comparability between the two groups at preintervention on sociodemographics, disease-related variables, and psychological measures, a series of t tests and chi-square tests were conducted. If baseline group differences were found on any variables, baseline scores on that variable were entered as covariates in all subsequent analyses. Psychological questionnaire data were checked for outliers and violations of the assumption of normality.

Effect of MBSR Participation

To test for an impact of MBSR on depressive symptoms, mindfulness, and rumination, three ANCOVAs were conducted with group (MBSR vs. Control) as the independent variable, Time 2 scores as the dependent variable, and Time 1 scores as the covariate.

Effect size estimates were obtained comparing pre- and post-intervention means (and their respective pre- and post-intervention standard deviations) for the CESD-10, MAAS, and Rumination–Reflection Questionnaire—Rumination subscale (RRQ-Rum), for the intervention and control groups. Cohen’s d was calculated using gain scores and pooled standard deviations using the standard formula: \( d = {{{M_{\rm{pre}}}--{M_{\rm{post}}}} \mathord{\left/{\vphantom {{{M_{\rm{pre}}}--{M_{\rm{post}}}} \sigma }} \right.} \sigma } \) pooled; σ \( {\hbox{spooled}} = \surd \left( {{{\left( {{\hbox{s}}_{\rm{pre}}^2 + {\hbox{s}}_{\rm{post}}^2} \right)} \mathord{\left/{\vphantom {{\left( {{\hbox{s}}_{\rm{pre}}^2 + {\hbox{s}}_{\rm{post}}^2} \right)} {2}}} \right.} {2}}} \right) \) (Cohen 1988) and was corrected for dependence between means (Morris and DeShon 2002). Effect sizes for improvements (e.g., reductions in depressive symptoms) are reported as positive in sign as per current conventions (Rosnow and Rosenthal 1996).

Mediation Analyses

Two separate mediation analyses were conducted to determine whether reductions in depressive symptoms associated with MBSR participation were mediated by: (1) increases in mindfulness and (2) reductions in rumination. First, change scores (post-test minus pretest scores) were computed for the CESD-10, MAAS, and RRQ-Rum scales. Second, the widely used causal steps mediation approach (Baron and Kenny 1986) was applied. This regression-based mediation model assumes that the independent variable is associated with changes in the mediator, the latter of which are associated with changes in the outcome, above and beyond the direct effect of the independent variable on outcome (Baron and Kenny 1986). Third, following recommendations for examining mediation (MacKinnon et al. 2002, 2004), a nonparametric bootstrapping procedure for testing the statistical significance of the indirect (mediated) effects was applied (Preacher and Hayes 2008; Shrout and Bolger 2002). This method offers more power than more traditional approaches while maintaining reasonable control over the Type I error rate and does not incorrectly assume that the sampling distribution of the indirect effect is symmetrical or normal (Fritz and Mackinnon 2007; MacKinnon et al. 2002; Preacher and Hayes 2008). Preacher and Hayes’ (2004) SPSS bootstrapping script was used to derive bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (95%) for the indirect effect of group (MBSR vs. control) through the hypothesized mediators (change in mindfulness and rumination) on change in depression scores. Five thousand repeated random samples were taken from the original data to compute the indirect effect. Mediation is said to occur if the derived confidence interval does not contain zero (Preacher and Hayes 2004).

Results

Participant Flow

Screening, eligibility, consent, and dropout rates are presented in Fig. 3. Treatment group participants were considered to have dropped out if they attended fewer than 50% of the MBSR classes (i.e., <5 out of nine, including the 6-h workshop) and/or did not return for the Time 2 assessment. Ten treatment group participants and three control group participants dropped out. Participants’ primary reason for dropping out was “being too busy to continue.” Missing values were imputed using the last-observation-carried-forward method, for participants who did not return for the Time 2 assessment (n = 11). The final intent-to-treat sample consisted of 46 treatment group and 31 control participants.

No differences were observed between participants who dropped out and those who completed the study on any baseline variable, with the exception of amount of education. Those who completed the study had more years of education (M = 14.86, SD = 1.55) when compared to those who dropped out (M = 13.69, SD = 2.09; t(75) = 2.31, p = .03; Levene’s test was significant, F(1,75) = 5.20, p = .03).

Demographics and Baseline Values

Full demographic data are presented in Table 1. Group pre- and post-intervention means and standard deviations on the psychological measures are presented in Table 2. The majority of participants (76.6%; n = 59) had breast cancer, with other types of cancer including gynecological (n = 3), gastrointestinal (n = 4), lung (n = 1), bladder (n = 1), lymphoma (n = 2), melanoma (n = 2), soft-tissue sarcoma (n = 1), adenocarcinoma (n = 1), spinal (n = 1), multiple myeloma (n = 1), and leukemia (n = 1). A minority of patients had metastatic disease (n = 6). Most of the women were Caucasian (86%), worked fewer than 20 h/week (65%), and were married or living with a partner (75%). At the first assessment, the percentage of women who were taking adjuvant hormone treatment (e.g., Tamoxifen), antidepressant, and sleeping medications was 55%, 29%, and 18%, respectively.

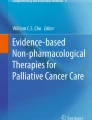

Path diagram representing a the direct relation between group status (intervention vs. control) and changes in depression scores and b the mediation model for changes in rumination on the relation between group status (intervention versus control) and changes in depression scores. Standardized beta estimates are shown, with p values in parentheses. Although group status initially predicted differences in depression change scores, this relation was no longer significant when changes in rumination are entered into the model.

T tests revealed no significant group differences on any sociodemographic, medical, or psychological variable except marital status and depression scores. At pre-intervention, treatment group participants were more likely to be married or living with a common-law partner (versus being divorced, separated, widowed, or single), when compared with the control group (84% vs. 61%) (χ2(1) = 5.25, p < .05), and had significantly higher CESD-10 scores than controls (M = 10.87, SD = 6.98 and M = 7.55, SD = 4.98, respectively; t(75) = 2.28, p < .05; Levene’s test was significant, F(1,75) = 4.96, p < .05). Baseline CESD-10 scores were, therefore, entered as covariates in all subsequent analyses.

Adherence

The average attendance of treatment group participants (n = 46) in the MBSR program was 88.9% (i.e., a mean of eight out of a possible nine sessions, including the 6-h workshop). Thirty-one out of 32 MBSR program completers returned their meditation log sheets. The average self-reported compliance with meditation and yoga practice at home was 73.3%; excluding the time spent in the weekly groups, MBSR participants reported practicing for an average of 33 min/day (SD = 18.4).

Psychological Questionnaires

CESD-10 scores were positively skewed at Times 1 and 2 (skewness >2.0) despite the absence of significant outliers. Log-transformed CESD-10 scores were used in all ANCOVAs.

Analyses revealed that the MBSR group demonstrated significantly lower CESD-10 scores at Time 2 when compared with the control group, controlling for baseline CESD-10 scores (F(1,73) = 5.25, p < .05; Table 2). The effect size for the reduction in depressive symptoms was large for the MBSR group (d = .78) and small for the waitlist control group (d = .11) (Cohen 1977; Morris and DeShon 2002). At Time 2, MAAS scores were significantly greater in the MBSR group when compared with the control group, controlling for baseline CESD-10 and MAAS scores (F(1,72) = 12.81, p < .01). The effect size for MAAS change was medium for the MBSR group (d = .57) and small for the control group (d = .19). Finally, Time 2 scores on the RRQ-Rum were significantly lower in the MBSR group when compared with controls, controlling for baseline RRQ-Rum and CESD-10 scores (F(1,72) = 11.04, p < .01). Effect sizes for reductions in rumination were large for the MBSR group (d = .92) and small for the control group (d = .30).

Mediation Analyses

Mindfulness

To satisfy Step 1 of the causal steps mediation analysis (Baron and Kenny 1986), using a linear regression approach, the independent variable (treatment group) must account for a significant proportion of the variability in the dependent variable (change in depression scores). The effect of treatment group on change in depression scores was significant (standardized β = .23, p < .05), establishing that there was an effect that may be mediated (Fig. 4a). In Step 2 of the analysis, a regression is run to determine whether the independent variable is associated with change in the mediator. A significant effect of treatment group on mindfulness change was observed (standardized β = −.35, p < .01). In Step 3, change in the mediator must predict change in the dependent variable, when controlling for the independent variable. Our data showed that mindfulness change scores were not significantly associated with depression score change, when controlling for treatment group (standardized β = −.19, p = .06). Results of the bootstrap analysis testing mindfulness as a mediator indicated that the true indirect effect was estimated to lie between −.034 and 1.495 with 95% confidence (the 95% confidence interval contains 0), indicating that change in mindfulness did not mediate the effect of treatment group on depressive symptoms.

Rumination

Results of a linear regression established that the effect of treatment group on change in depression scores was significant, satisfying Step 1 of the mediation analysis (standardized β = .23, p < .05). In Step 2, a significant effect of treatment group on rumination change was observed (standardized β = .35, p < .01) (Fig. 4b). In Step 3, rumination change scores were positively associated with depression score change, controlling for treatment group (standardized β = .31, p < .01). In Step 4, the effect of treatment group on depression change was reduced and became statistically nonsignificant when controlling for the effects of rumination change (standardized β = .12, p = .24), establishing that rumination change completely mediated the impact of treatment group on depression change. Results of the bootstrap analysis indicated that the true indirect effect was estimated to lie between .324 and 2.163 with 95% confidence (the 95% confidence interval does not contain 0), confirming that rumination did act as a mediator.

Discussion

The present study set out to confirm previously observed benefit of MBSR for decreasing depressive symptoms in women with cancer and to test the potential mediating roles of increases in mindfulness and decreases in rumination on this effect. In terms of the first objective, women with cancer who participated in the MBSR program reported fewer depressive symptoms following the intervention when compared with a waitlist control group, adjusting for baseline depression scores. This finding is consistent with a recent randomized waitlist-controlled trial of a 6-week MBSR program showing decreased adjusted depression scores in women with breast cancer (Lengacher et al. 2009). At study outset, a large proportion of participants exceeded the CESD-10 clinical cutoff score for depressive symptoms (42% in total sample; 51% in treatment group; and 29% in control group). This percentage is comparable to depression prevalence rates when the full-length CES-D scale has been used in breast cancer patient samples (Lasry et al. 1987). By the end of the 8-week program, 22% of MBSR participants whose scores initially met or exceeded the cutoff for depressive symptoms no longer met the cutoff (compared to no change in the control group). The MBSR group’s effect size for change in depressive symptoms (Cohen’s d = .78) exceeds that which is generally considered to represent a clinically meaningful treatment effect (i.e., d ≥ 0.5) (Norman et al. 2003). In oncology populations, reducing depressive symptoms may have implications for the quality of life and survivorship of the large proportion of patients who experience these symptoms (Onitilo et al. 2006; Prieto et al. 2005; Satin et al. 2009; Spiegel and Giese-Davis 2003; Watson et al. 2005).

Women in the MBSR group also demonstrated greater mindfulness and less rumination following the intervention when compared with the waitlist group, adjusting for baseline scores. Our results are consistent with studies showing that mindfulness-based interventions decrease ruminative thought processes and enhance mindfulness in clinical and nonclinical populations (Astin 1997; Jain et al. 2007; Ma and Teasdale 2004; Ramel et al. 2004; Shapiro et al. 1998; Teasdale et al. 2000; Williams et al. 2001). Moreover, the impact of MBSR on depressive symptoms was found to be mediated by reductions in rumination, pointing to a possible mechanism of MBSR for this specific outcome. Interestingly, the MBSR program does not explicitly target depressogenic cognitive styles and content as do other interventions with mindfulness and/or cognitive components (e.g., Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (Segal et al. 2002, 2005)). One could hypothesize that practicing observing one’s thoughts, emotions, and body sensations, with discernment rather than judgment, is a common active component leading to reduced rumination and depressive symptoms in cognitive and mindfulness-based interventions.

However, changes in mindfulness did not mediate the association between MBSR participation and decreased depressive symptoms. This finding is inconsistent with studies that have shown a mediating effect of mindfulness in distressed and student samples (Nyklicek and Kuijpers 2008; Shapiro et al. 2008), although depression was not measured as an outcome in this research. Nyklicek and Kuijpers (2008) found mindfulness-mediated changes in perceived stress and quality of life, while the Shapiro et al (2008) study also found a mediating effect on perceived stress. It may be the case that clinical symptoms of depression are not as highly amenable to change through increases in mindfulness as more general outcomes such as stress levels. Mechanisms more closely associated with the process of initiation and maintenance of depression also impacted by MBSR, such as the observed decrease in rumination, may be more directly involved in the decrease in depressive symptoms than a general increase in mindfulness.

In addition to decreased rumination, other program components may lead to decreased depressive symptoms in women with cancer. For example, patient expectancies (“placebo effect”), warm and empathetic interactions with a facilitator, and receiving group support may all play a role in reducing patient distress (Carmody and Baer 2008). Other program components exerting an effect may include relaxation or being introduced to thought monitoring and cognitive restructuring, none of which were tested in this study as potential mediators. It is also plausible that participants developed qualities of attending to experience that are not fully captured by the mindfulness questionnaire used in the study. Future studies examining the specificity of mindfulness and rumination as mechanisms of MBSR in cancer patients on a variety of outcomes are warranted.

There are several important methodological limitations of the current study that merit comment. Participants were not randomized into MBSR and waitlist control groups, as the majority were unwilling to wait to take the program should they be assigned to the control condition—hence, the use of a natural waitlist control. This aspect of the study design reflects the high levels of distress typical of individuals with cancer who seek to participate in MBSR (Amato et al. 1998). It follows that factors other than the intervention itself may have contributed to change in mediator and outcome variables, including regression towards the mean (particularly given that depression scores differed between groups at baseline). It should also be noted that mediation analyses cannot establish definitive causal links. However, they provide evidence that one mediation pattern is more plausible than another and offer valuable information for the design of fully experimental studies of causal processes (National Institute of Mental Health 2002; Shrout and Bolger 2002). Causal interpretation can be optimized in estimating mediation if investigators use psychometrically sound measures, base their hypotheses on strong theoretical support, and use recommended statistical approaches for evaluating mediators (Watson et al. 1999). Randomized, component-controlled, or “dismantling” studies will permit stronger conclusions regarding mechanisms of action. For example, isolating didactic content (e.g., introduction to types of cognitive distortions) and meditation practice to separate study arms will show which MBSR program components lead to changes in mindfulness, rumination, depressive symptoms, and other outcomes. Use of different methods and measures accumulates evidence for mediational processes and helps rule out alternative explanations of an observed mediation effect (MacKinnon 2008).

Several other measurement issues should be taken into consideration. In order to adequately address the question of mediation, investigators must first identify mediational constructs and determine the most appropriate ways to measure them. The majority of MBSR studies conducted to date have used self-report questionnaires to assess psychological constructs. Many factors can interfere with accurate self-report, including impression management (e.g., participants may want to show that they have benefited from the program) and repressive coping styles (i.e., tendency to minimize emotional distress) (Temoshok 2000). Strategies may be applied to minimize these effects, by developing and using more objective measures of mindfulness and emotion regulation (e.g., cognitive paradigms, behavioral observation, physiological measures, and/or neuroimaging) (Shapiro et al. 2006). It is also recommended that investigators assess temporal precedence (i.e., whether earlier changes in mediating variables account for later changes in outcomes); doing so requires repeated assessment of mediators before, during, and after an intervention but allows for stronger conclusions regarding mechanisms of action. Decisions regarding when to measure mediators should be based on the predicted timing of treatment-related change (MacKinnon 2008).

In oncology settings, an assessment of mediators of MBSR could consider variables of specific relevance to this patient population. For example, cancer-specific worry (e.g., worry about recurrence, the impact of treatment on family life and finances) is commonly experienced but may represent an ineffective emotion regulation strategy (Cameron and Diefenbach 2001; Mullens et al. 2004). Participating in MBSR may reduce the tendency to worry about cancer recurrence, resulting in fewer stress symptoms. When assessing psychosocial interventions tailored for an oncology population, mediation effects may be strongest for areas of functioning most affected by the cancer experience. To the extent that MBSR engenders gentle, nonjudgmental, present-focused attention, unhelpful and habitual rumination on past hurt, failure and injustice may fall away, thus improving patient well-being and quality of life. Testing this mediation model in a rigorous manner will inform our understanding of mindfulness-based interventions and may lead to program modifications that will maximize the effectiveness of MBSR in oncology settings.

References

Adler, N. E., Page, A., National Institute of Medicine, & Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients / Families in a Community Setting. (2008). Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Amato, J. J., Williams, M., Greenberg, C., Bar, M., Lo, S., & Tepler, I. (1998). Psychological support to an autologous bone marrow transplant unit in a community hospital: A pilot experience. Psycho-Oncology, 7(2), 121–125.

Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (center for epidemiologic studies depression scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84.

Astin, J. A. (1997). Stress reduction through mindfulness meditation: effects on psychological symptomatology, sense of control, and spiritual experiences. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 66, 97–106.

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 125–143.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J. F., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 11, 230–241.

Boey, K. W. (1999). Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(8), 608–617.

Bonadona, V., Saltel, P., Desseigne, F., Mignotte, H., Saurin, J. C., Wang, Q., et al. (2002). Cancer patients who experienced diagnostic genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: Reactions and behavior after the disclosure of a positive test result. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 11(1), 97–104.

Bower, J. E. (2008). Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast cancer and survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26(5), 768–777.

Bredart, A., Autier, P., Audisio, R. A., & Geragthy, J. (1998). Psycho-social aspects of breast cancer susceptibility testing: A literature review. European Journal of Cancer Care (Engl.), 7(3), 174–180.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Cameron, L. D., & Diefenbach, M. A. (2001). Responses to information about psychosocial consequences of genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: Influences of cancer worry and risk perceptions. Journal of Health Psychology, 6(1), 47–59.

Carlson, L. E., & Brown, K. W. (2005). Validation of the mindful attention awareness scale in a cancer population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 29–33.

Carlson, L. E., & Garland, S. N. (2005). Impact of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on sleep, mood, stress and fatigue symptoms in cancer outpatients. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 12, 278–285.

Carlson, L. E., Labelle, L. E., Garland, S. N., Hutchins, M. L., & Birnie, K. (2009). Mindfulness-based interventions in oncology. In F. Didonna (Ed.), Clinical handbook of mindfulness (pp. 383–404). New York: Springer.

Carlson, L. E., & Speca, M. (2010). Mindfulness-based cancer recovery: A step-by-step MBSR approach to help you cope with treatment and reclaim your life. Oakville: New Harbinger. In Press.

Carlson, L. E., Speca, M., Patel, K. D., & Faris, P. (2007). One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 21, 1038–1049.

Carlson, L. E., Speca, M., Patel, K. D., & Goodey, E. (2003). Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress, and immune parameters in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(4), 571–581.

Carlson, L. E., Speca, M., Patel, K. D., & Goodey, E. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress and levels of cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and melatonin in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(4), 448–474.

Carlson, L. E., Ursuliak, Z., Goodey, E., Angen, M., & Speca, M. (2001). The effects of a mindfulness meditation based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients: Six month follow-up. Supportive Care in Cancer, 9, 112–123.

Carmody, J., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31, 23–33.

Carmody, J., Baer, R. A., Lykins, E. L. B., & Olendzki, N. (2009). An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(6), 613–626.

Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 560–572.

Cheng, S. T., & Chan, A. C. (2005). The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in older Chinese: Thresholds for long and short forms. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(5), 465–470.

Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (revisedth ed.). New York: Academic.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dimeo, F., Bertz, H., Finke, J., Fetscher, S., Mertelsmann, R., & Keul, J. (1996). An aerobic exercise program for patients with haematological malignancies after bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 18(6), 1157–1160.

Dobkin, P. L. (2008). Mindfulness-based stress reduction: What processes are at work? Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 14(1), 8–16.

Epstein, M. (1995). Thoughts without a thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist perspective. New York: Basic Books.

Fritz, M. S., & Mackinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239.

Garland, S. N., Carlson, L. E., Cook, S., Lansdell, L., & Speca, M. (2007). A non-randomized comparison of mindfulness-based stress reduction and healing arts programs for facilitating post-traumatic growth and spirituality in cancer outpatients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 15(8), 949–961.

Germer, C. K. (2005). Mindfulness: What is it? what does it matter? In C. K. Germer, R. D. Siegel, & P. R. Fulton (Eds.), Mindfulness and psychotherapy (pp. 3–27). New York: Guilford.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299.

Hopwood, P. (1997). Psychological issues in cancer genetics: Current research and future priorities. Patient Education and Counselling, 32(1–2), 19–31.

Hopwood, P., Keeling, F., Long, A., Pool, C., Evans, G., & Howell, A. (1998). Psychological support needs for women at high genetic risk of breast cancer: Some preliminary indicators. Psycho-Oncology, 7(5), 402–412.

Horner, M. J., Ries, L. A. G., Krapcho, M., Neyman, N., Aminou, R., Howlader, N., et al. (2009). SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2006. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute.

Jain, S., Shapiro, S. L., Swanick, S., Roesch, S. C., Mills, P. J., Bell, I., et al. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(1), 11–21.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4, 33–47.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York: Delacourt.

Kash, K. M., Holland, J. C., Halper, M. S., & Miller, D. G. (1992). Psychological distress and surveillance behaviors of women with a family history of breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 84(1), 24–30.

Keller, M. (2000). Psychosocial issues in cancer genetics: State of the art. Zeitschrift fur Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychoanalyse, 46(1), 80–97.

Kim, Y. S., Jun, H., Chae, Y., Park, H. J., Kim, B. H., Chang, I. M., et al. (2005). The practice of Korean medicine: An overview of clinical trials in acupuncture. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2(3), 325–352.

Kraemer, H. C., Wilson, G. T., Fairburn, C. G., & Agras, W. S. (2002). Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(10), 877–883.

Kramer, J. H., Crittenden, M. R., DeSantes, K., & Cowan, M. J. (1997). Cognitive and adaptive behavior 1 and 3 years following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 19(6), 607–613.

Lamanque, P., & Daneault, S. (2006). Does meditation improve the quality of life for patients living with cancer? Canadian Family Physician Medecin De Famille Canadien, 52, 474–475.

Lasry, J. C., Margolese, R. G., Poisson, R., Shibata, H., Fleischer, D., Lafleur, D., et al. (1987). Depression and body image following mastectomy and lumpectomy. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40(6), 529–534.

Lau, M. A., Bishop, S. R., Segal, Z. V., Buis, T., Anderson, N. D., Carlson, L., et al. (2006). The Toronto mindfulness scale: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(12), 1445–1467.

Ledesma, D., & Kumano, H. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cancer: A meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology, 18(571), 579.

Lengacher, C. A., Johnson-Mallard, V., Post-White, J., Moscoso, M. S., Jacobson, P. B., Klein, T. W., et al. (2009). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for survivors of breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 18(12), 1261–1272.

Lerman, C., Daly, M., Sands, C., Balshem, A., Lustbader, E., Heggan, T., et al. (1993). Mammography adherence and psychological distress among women at risk for breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85(13), 1074–1080.

Lerman, C., Lustbader, E., Rimer, B., Daly, M., Miller, S., Sands, C., et al. (1995). Effects of individualized breast cancer risk counseling: A randomized trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 87(4), 286–292.

Lerman, C., & Schwartz, M. (1993). Adherence and psychological adjustment among women at high risk for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 28(2), 145–155.

Ma, S. H., & Teasdale, J. D. (2004). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: Replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 72(1), 31–40.

Mackenzie, M. J., Carlson, L. E., Munoz, M., & Speca, M. (2007). A qualitative study of self-perceived effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in a psychosocial oncology setting. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 23(1), 59–69.

Mackenzie, M. J., Carlson, L. E., & Speca, M. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in oncology: Rationale and review. Evidence Based Integrative Medicine, 2, 139–145.

MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Erlbaum.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128.

Matchim, Y., & Armer, J. M. (2007). Measuring the psychological impact of mindfulness meditation on health among patients with cancer: A literature review. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34(5), 1059–1066.

Morris, S. B., & DeShon, R. P. (2002). Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 105–125.

Mullens, A. B., McCaul, K. D., Erickson, S. C., & Sandgren, A. K. (2004). Coping after cancer: Risk perceptions, worry, and health behaviors among colorectal cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 13(6), 367–376.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2002). Psychotherapeutic interventions: How and why they work. Bethesda: National Institute of Mental Health.

Norman, G. R., Sloan, J. A., Wyrwich, K. W., & Norman, G. R. (2003). Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical Care, 41, 582–592.

Nyklicek, I., & Kuijpers, K. F. (2008). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention on psychological well-being and quality of life: Is increased mindfulness indeed the mechanism? Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 35(3), 331–340.

Onitilo, A. A., Nietert, P. J., & Egede, L. E. (2006). Effect of depression on all-cause mortality in adults with cancer and differential effects by cancer site. General Hospital Psychiatry, 28(5), 396–402.

Ott, M. J., Norris, R. L., & Bauer-Wu, S. M. (2006). Mindfulness meditation for oncology patients. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 5, 98–108.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Prieto, J. M., Atala, J., Blanch, J., Carreras, E., Rovira, M., Cirera, E., et al. (2005). Role of depression as a predictor of mortality among cancer patients after stem-cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(25), 6063–6071.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Ramel, W., Goldin, P. R., Carmona, P. E., & McQuaid, J. R. (2004). The effects of mindfulness meditation on cognitive processes and affect in patients with past depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28, 433–455.

Rosnow, R. L., & Rosenthal, R. (1996). Computing contrasts, effect sizes, and counternulls on other people's published data: General procedures for research consumers. Psychological Methods, 1(4), 331–340.

Satin, J. R., Linden, W., & Phillips, M. J. (2009). Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Cancer, 115(22), 5349–5361.

Segal, Z. V., Bizzini, L., & Bondolfi, G. (2005). Cognitive behaviour therapy reduces long term risk of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder. Evidence Based Mental Health, 8, 38.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford.

Shapiro, S. L., & Carlson, L. E. (2009). The art and science of mindfulness: Integrating mindfulness into psychology and the helping professions. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 373–386.

Shapiro, S. L., Oman, D., Thoresen, C. E., Plante, T. G., & Flinders, T. (2008). Cultivating mindfulness: Effects on well-being. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(7), 840–862.

Shapiro, S. L., Schwartz, G. E., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21, 581–599.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445.

Smith, J. E., Richardson, J., Hoffman, C., & Pilkington, K. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction as supportive therapy in cancer care: Systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52, 315–327.

Spahn, G., Lehmann, N., Franken, U., Paul, A., Longhorst, J., Michalsen, A., et al. (2003). Improvement of fatigue and role function of cancer patients after an outpatient integrative mind-body intervention. Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 8(4), 540.

Speca, M., Carlson, L. E., Goodey, E., & Angen, M. (2000). A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: The effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(5), 613–622.

Speca, M., Carlson, L. E., Mackenzie, M. J., & Angen, M. (2006). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) as an intervention for cancer patients. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: A clinician's guide to evidence base and approaches (pp. 239–261). Burlington: Elsevier.

Spiegel, D., & Giese-Davis, J. (2003). Depression and cancer: Mechanisms and disease progression. Biological Psychiatry, 54, 269–282.

Teasdale, J. D., & Green, H. A. (2004). Ruminative self-focus and autobiographical memory. Personality & Individual Differences, 36, 1933–1943.

Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M., Ridgeway, V. A., Soulsby, J. M., & Lau, M. A. (2000). Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 615–623.

Temoshok, L. R. (2000). Psychological response and survival in breast cancer. Lancet, 355(920), 404–405.

Temoshok, L. R., & Wald, R. L. (2002). Change is complex: Rethinking research on psychosocial interventions and cancer. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 1(2), 135–145.

Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 76, 284–304.

Van Wielingen, L. E., Carlson, L. E., & Campbell, T. S. (2007). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), blood pressure, and psychological functioning in women with cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69, A43.

Verhoef, M. J., Casebeer, A. L., & Hilsden, R. J. (2002). Assessing efficacy of complementary medicine: Adding qualitative research methods to the "gold standard". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 8(3), 275–281.

Vickers, A. J. (1996). Can acupuncture have specific effects on health? A systematic review of acupuncture antiemesis trials. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 89(6), 303–311.

Vickers, A. J. (2004). Statistical reanalysis of four recent randomized trials of acupuncture for pain using analysis of covariance. Clinical Journal of Pain, 20(5), 319–323.

Vickers, A. J., Rees, R. W., Zollman, C. E., McCarney, R., Smith, C. M., Ellis, N., et al. (2004). Acupuncture of chronic headache disorders in primary care: Randomised controlled trial and economic analysis. Health Technology Assessment, 8(48), 1–35.

Watanabe, S., & Bruera, E. (1996). Anorexia and cachexia, asthenia, and lethargy. Hematology/oncology Clinics of North America, 10(1), 189–206.

Watson, M., Haviland, J. S., Greer, S., Davidson, J., & Bliss, J. M. (1999). Influence of psychological response on survival in breast cancer: A population-based cohort study. Lancet, 354(9187), 1331–1336.

Watson, M., Homewood, J., Haviland, J., & Bliss, J. M. (2005). Influence of psychological response on breast cancer survival: 10-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. European Journal of Cancer, 41(12), 1710–1714.

Wetzel, W. (1989). Reiki healing: A physiologic perspective. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 7(1), 47–54.

White, A., & Ernst, E. (2003). Pitfalls in conducting systematic reviews of acupuncture. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 42(10), 1271–1272.

White, A., & Ernst, E. (2004). A brief history of acupuncture. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 43(5), 662–663.

Williams, K. A., Kolar, M. M., Reger, B. E., & Pearson, J. C. (2001). Evaluation of a wellness-based mindfulness stress reduction intervention: A controlled trial. American Journal of Health Promotion, 15, 422–432.

Witek-Janusek, L., Albuquerque, K., Chroniak, K. R., Chroniak, C., Durazo-Arvizu, R., & Mathews, H. L. (2008). Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity, 22(6), 969–981.

Wonderling, D., Vickers, A. J., Grieve, R., & McCarney, R. (2004). Cost effectiveness analysis of a randomised trial of acupuncture for chronic headache in primary care. BMJ, 328(7442), 747.

Yano, K., Kanie, T., Okamoto, S., Kojima, H., Yoshida, T., Maruta, I., et al. (2000). Quality of life in adult patients after stem cell transplantation. International Journal of Hematology, 71(3), 283–289.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Carlson holds the Enbridge Research Chair in Psychosocial Oncology, co-funded by the Canadian Cancer Society Alberta/NWT Division and the Alberta Cancer Foundation, and is an Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Health Scholar. This study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Breast Cancer Research Alliance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Labelle, L.E., Campbell, T.S. & Carlson, L.E. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in Oncology: Evaluating Mindfulness and Rumination as Mediators of Change in Depressive Symptoms. Mindfulness 1, 28–40 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0005-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0005-6