Abstract

Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (FDCS) is a rare entity which can share morphologic features with non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Recent reports suggest that up to half of FDCSs show immunohistochemical positivity for p16 (Zhang et al., in Hum Pathol 66:40–47, 2017), a stain that is conventionally used in the risk stratification of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC). Herein, we report a case of p16-positive FDCS with clinical and histomorphologic overlap with human papilloma virus (HPV)-related OPSCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Follicular dendritic cells contribute to the stroma of lymphoid tissues, where they are found in germinal centers and function to present antigens to B cells during the immune response. They are immunohistochemically characterized by positivity for follicular dendritic cell markers such as CD21, CD23, and CD35. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (FDCS) is a very rare malignant proliferation of follicular dendritic cells first described by Monda et al. in 1986 [1]. FDCS afflicts men and women equally, with a median age of 50 years [2] at the time of presentation. FDCS often presents as a painless, slow-growing nodal mass, although it can also arise in extranodal locations [3]. This malignant proliferation may arise in association with the hyaline vascular variant of Castleman Disease, but most frequently appears de novo. Rarely, it is associated with myasthenia gravis. Pathogenic alterations in genes involving the NFĸB pathway and BRAF V600E are often present [4,5,6]. There is no standard treatment for FDCS, although most patients undergo complete surgical resection with or without subsequent radiation and/or chemotherapy. Although FDCS typically follows a protracted clinical course with a median survival of > 10 years in patients with localized disease [2, 3], nearly half of patients experience local recurrence and/or distant metastasis after initial treatment. Herein we report an unusual case of FDCS of the tonsil with histologic p16 positivity mimicking a human papilloma virus (HPV)-related non-keratinizing oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC).

Case History

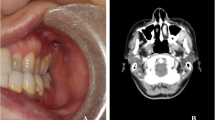

A previously healthy 39-year-old non-smoking man presented with 3 months of posterior throat fullness, excessive snoring during sleep, and episodic night sweats. He had no personal or family history of cancer. Physical exam revealed asymmetric tonsillar hypertrophy with an ill-defined mass of the right tonsil. A CT scan showed asymmetric enlargement of the right palatine tonsil to 2.8 cm in diameter, which was felt to be non-specific, representing either a mass or reactive hyperplasia. The remainder of the pharynx was normal and there was no lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1). A bilateral tonsillectomy was performed. Intraoperative examination of the oropharynx revealed a grade 4 right tonsil and a grade 2.5 left tonsil. The soft palate and uvula were unremarkable.

Gross examination of the tonsillectomy specimen revealed that the right tonsil measured 4.0 cm in maximum dimension and displayed a tan to pink, fleshy, smooth, homogenous cut surface, as opposed to the cerebriform texture of the grossly normal left tonsil. There was no evidence of a clonal lymphoproliferative disorder in either tonsil by flow cytometry.

On histology, the right tonsil contained a well-circumscribed but unencapsulated mass measuring 2.0 cm. The mass was composed of sheets and poorly formed fascicles of medium-sized epithelioid to ovoid cells with eosinophilic and somewhat fibrillary cytoplasm (Fig. 2). The cells had elongated nuclei with dispersed chromatin, occasional small nucleoli, and nuclear pseudoinclusions. Occasional multinucleated giant cells were also present. The mass contained a mild infiltrate of small, mature-appearing lymphocytes which clustered around the small vessels scattered throughout the lesion. There was no necrosis and mitotic figures were rare.

Immunohistochemical stains revealed that > 70% of the atypical cells were p16-positive (with p16-positive cells showing both cytoplasmic and nuclear staining), but negative for epithelial (OSCAR, pankeratin, p63, EMA), melanoma (HMB45, Mart 1, SOX10), muscle (desmin, myogenin, SMA), schwannoma (S100), neuroendocrine (synaptophysin, chromogranin), lymphoid (CD45), and Langerhans cell (CD1a, langerin) markers (Fig. 3). INI expression was retained. In situ hybridization (ISH) revealed no evidence of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) by EBER or HPV 16/18. The proliferation index was 30% via Ki67 staining. PCR for high-risk HPV was negative.

Although initial suspicion for HPV-related OPSCC was high given the congruent clinical presentation, histology on routine stains, and p16 positivity, the lesion was negative for keratins and showed no evidence of HPV by ISH or PCR, making this diagnosis unlikely. Upon further examination, the fibrillary quality of the cytoplasm and the nuclear pseudoinclusions seen within the lesional cells, as well as the presence and pattern of the lymphocytic infiltrate within the lesion raised suspicion for FDCS. Immunohistochemical stains for follicular dendritic cell markers CD21, CD23, and CD35 were added and were strongly and diffusely positive (Fig. 4).

On this basis, the patient was diagnosed with follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Follow-up immunohistochemical staining for BRAF V600E was negative. An additional stain revealed retention of Rb within the lesional cells.

Following initial resection of the mass, re-excision of the tumor bed was performed revealing no residual tumor. The patient was screened for Castleman’s Disease and myasthenia gravis and was negative for both. Plans were made to monitor closely via imaging.

Discussion

Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma is a rare entity whose clinical and histologic presentation as a tonsillar mass can closely mimic a non-keratinizing oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC). Both entities frequently present as a painless mass in the head and neck of a middle-aged male, as in this case. Moreover, a FDCS composed primarily of epithelioid dendritic cells, as presented here, exhibits histomorphologic overlap with non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. This poses a diagnostic pitfall, particularly in the pharyngeal region where carcinomas are much more common.

A literature review performed by Duan et al. found that 58% of cases of extranodal FDCS were initially misdiagnosed, often mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma [7]. Further complicating the distinction between FDCS and epithelial lesions, a subset of FDCSs show focal positivity for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA; not present in this case) [8].

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma also shares some histologic features with FDCS, although this tumor is usually EBV-related (and therefore EBER-positive) and includes a more prominent inflammatory component within the carcinoma. In the case reported here, the diffuse negativity of the lesional cells for keratins helped exclude carcinoma from the differential diagnosis.

The histologic differential diagnosis in this case also included metastatic melanoma (excluded by immunohistochemical negativity for S100, HMB-45, Mart 1, and SOX10). Negativity for S100, along with CD45, also helped exclude interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma, which has significant cellular morphologic overlap with FDCS, including the presence of admixed of small lymphocytes. Langerhans cell histiocytosis was also excluded by negativity for S100, as well as for CD1a and langerin. Ultimately, the strong and diffuse immunohistochemical positivity for follicular dendritic cell markers CD21, CD23, and CD35 confirmed the final diagnosis.

While the epithelioid morphology of the lesional cells in this case resembled carcinoma, neoplastic follicular dendritic cells are often spindled, invoking a differential of other spindle-cell sarcomas. Yet another differential that warrants consideration is the inflammatory pseudotumor-like variant of FDCS, which is composed of follicular dendritic cells dispersed in a heavily inflammatory background of lymphocytes and plasma cells and often shows fibrinous changes of intratumoral vasculature. This variant arises most frequently in the spleen or liver of female patients and unlike other FDCSs, is frequently associated with EBV (and is thus EBER-positive by immunohistochemistry and ISH) [9]. Occasionally, the cytomorphology of the lesional cells in FDCS may resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. These lesions are distinguishable from true Hodgkin lymphoma by a paucity of granulocytes in the inflammatory milieu as well as the diffuse architecture of atypical cells, which would be fewer and more dispersed in Hodgkin lymphoma.

The differential diagnosis of FDCS is broad, but it can often be limited by anatomic location of the lesion. In the case of a tonsillar lesion, an OPSCC is a particularly salient exclusion. FDCSs are characteristically indolent tumors, with histologically low-grade FDSCs having better clinical outcomes than their high-grade counterparts. Namely, intra-abdominal location, size ≥ 6 cm, the presence of coagulative necrosis, the presence of ≥ 5 mitotic figures per 10 high power fields, and prominent nuclear atypia have all been demonstrated to portend a poorer prognosis [2, 10]. This patient’s tumor lacked these characteristics, and as such, treatment with complete surgical excision alone would be appropriate. In contrast, an HPV-related OPSCC may be treated with radiation, chemoradiation, or surgical excision with or without radiation depending upon tumor size, margin, and lymph node status [11].

HPV-related non-keratinizing OPSCC is increasing in incidence in the United States and worldwide, affecting younger, healthier patients and showing a significantly better prognosis than non-HPV-related OPSCC [7]. Because of this, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the College of American Pathologists (CAP) recommend immunohistochemical staining for p16 on all OPSCCs to determine HPV status [12, 13]. In order to be considered positive, the p16 must stain with at least moderate intensity in > 70% of lesional cells [13], including both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining.

A recent case series by Zhang et al. demonstrated that 50% of the eight FDCS cases studied showed some p16 positivity by immunohistochemical staining, while 25% showed p16 staining of a strength and quantity sufficient to meet AJCC criteria for p16 positivity [10], as in this case. To our knowledge, there are only two other reports of p16-positivity in FDCS in the current English language literature. Although there are over 40 reports of oropharyngeal FDCS, the majority do not document lesional p16 expression by immunohistochemistry (Table 1). Of the three cases of oropharyngeal FDCS for which p16 immunohistochemistry results were reported, only our oropharyngeal case demonstrates p16 positivity.

While p16 overexpression in HPV-related OPSCC is due to viral inactivation of Rb leading to removal of Rb’s negative regulation of p16, the mechanism of p16 overexpression in FDCS seems to vary and may hint at the lesion’s molecular drivers. Recent targeted molecular analyses of FDCSs indicate that a minority of cases show alterations in Rb, while a larger number of FDCSs harbor alterations in CDKN2A, the gene which encodes p16 [5, 6]. It is possible that CDKN2A alterations lead to paradoxical overexpression of p16 due to downstream inactivation of Rb, again resulting in removal of the negative regulation by Rb of p16 [10]. In our case, immunohistochemical stains revealed both retention of Rb and negativity for the BRAF V600E mutation (another mutation recently identified as a possible pathogenic driver in FDCS [4]), raising the possibility that an alteration in CDKN2A may be driving the observed p16 overexpression.

Such p16-positive cases of FDCS can prove treacherous for the pathologist, who risks misclassifying these lesions as non-keratinizing OPSCCs. Because of the rarity of FDCS, p16 positivity may falsely affirm the diagnosis of HPV-related OPSCC if FDCS is not considered in the differential diagnosis. For rare cases such as the one presented here, the lack of reactivity for cytokeratins or p40 should alert the pathologist to this potential diagnostic pitfall. Subtle histomorphologic clues such as nuclear pseudoinclusions, which are present in approximately 43% of FDCSs [2], a lack of cohesive nests of cells, a lymphocytic infiltrate with perivascular cuffing [50], or fibrillary pink cytoplasm in the lesional cells may also raise suspicion for FDCS. If considered in the differential diagnosis, FDCS is easily diagnosed by positive staining for CD21, CD23 and/or CD35.

Conclusions

Although rare, FDCS should be considered in the differential of spindled to ovoid-cell neoplasms in the oropharynx. In p16-positive oropharyngeal lesions showing the subtle but characteristic histologic features of FDCS (spindled to ovoid cells with pseudonuclear inclusions and fibrillary cytoplasm) as in the case presented here, additional immunostaining with cytokeratin and follicular dendritic cell markers should be used to confirm or exclude the diagnosis [1].

References

Monda L, Warnke R, Rosai J. A primary lymph node malignancy with features suggestive of dendritic reticulum cell differentiation. A report of 4 cases. Am J Pathol. 1986;122:562–72.

Saygin C, Uzunaslan D, Ozguroglu M, Senocak M, Tuzuner N. Dendritic cell sarcoma: a pooled analysis including 462 cases with presentation of our case series. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88(2):253–71.

Perkins SM, Shinhara ET. Interdigitating and follicular dendritic cell sarcomas: a SEER analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36(4):395–8.

Go H, Jeon YK, Huh J, et al. Frequent detection of BRAF (V600E) mutations in histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms. Histopathology. 2014;65:261–72.

Massoth LR, Hung YP, Ferry JA, Hasserjian RP, Louissaint A, Montesion M, Sokol ES, Pavlick DC et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of 104 rare histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms reveals shared and distinct targetable genomic alterations. Blood. 2019;134(Supplement 1):2541.

Griffin GK, Sholl LM, Lindeman NI, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. Targeted genomic sequencing of follicular dendritic cell sarcoma reveals recurrent alterations in NF-κB regulatory genes. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:67–74.

Duan GJ, Wu F, Zhu J, Guo DY, Zhang R, Shen LL, Wang SH, Li Q, Xiao HL, Mou JH, Yan XC. Extranodal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the pharyngeal region: a potential diagnostic pitfall, with literature review. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133(1):49–58.

Wang RF, Han W, Qi L, Shan LH, Wang ZC, Wang LF. Extranodal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: a clinicopathological report of four cases and a literature review. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(1):391–8. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2014.2681.

Cheuk W, Chan JK, Shek TW, Chang JH, Tsou MH, Yuen NW, Ng WF, Chan AC, Prat J. Inflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular dendritic cell tumor: a distinctive low-grade malignant intra-abdominal neoplasm with consistent Epstein-Barr virus association. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:721–31.

Zhang L, Yang C, Lewis JS Jr, El-Mofty SK, Chernock RD. p16 expression in follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: a potential mimicker of human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2017;66:40–7.

Wang MB, Liu IY, Gornbein JA, Nguyen CT. HPV-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma: a systematic review of treatment and prognosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153(5):758–69.

Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer; 2016.

Lewis JS Jr, Beadle B, Bishop JA, Chernock RD, Colasacco C, Lacchetti C, Moncur JT, Rocco JW, Schwartz MR, Seethala RR, Thomas NE, Westra WH, Faquin WC. Human papillomavirus testing in head and neck carcinomas: guideline from the College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(5):559–97. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2017-0286-CP.

Chan JK, Tsang WY, Ng CS, Tang SK, Yu HC, Lee AW. Follicular dendritic cell tumors of the oral cavity. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(2):148–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199402000-00004.

Perez-Ordonez B, Erlandson RA, Rosai J. Follicular dendritic cell tumor: report of 13 additional cases of a distinctive entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20(8):944–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199608000-00003.

Nayler SJ, Verhaart MJ, Cooper K. Follicular dendritic cell tumour of the tonsil. Histopathology. 1996;28(1):89–92. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.t01-3-258289.

Chan JK, Fletcher CD, Nayler SJ, Cooper K. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 17 cases suggesting a malignant potential higher than currently recognized. Cancer. 1997;79(2):294–313.

Biddle DA, Ro JY, Yoon GS et al. Extranodal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the head and neck region: three new cases, with a review of the literature [published correction appears in Mod Pathol 2002 Apr; 15(4):475]. Mod Pathol. 2002;15(1):50–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880489.

Vargas H, Mouzakes J, Purdy SS, Cohn AS, Parnes SM. Follicular dendritic cell tumor: an aggressive head and neck tumor. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002;23(2):93–8. https://doi.org/10.1053/ajot.2002.30781.

Tisch M, Hengstermann F, Kraft K, von Hinüber G, Maier H. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsil: report of a rare case. Ear Nose Throat J. 2003;82(7):507–9.

Satoh K, Hibi G, Yamamoto Y, Urano M, Kuroda M, Nakamura S. Follicular dendritic cell tumor in the oro-pharyngeal region: report of a case and a review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2003;39(4):415–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1368-8375(02)00138-0.

Idrees MT, Brandwein-Gensler M, Strauchen JA, Gil J, Wang BY. Extranodal follicular dendritic cell tumor of the tonsil: report of a diagnostic pitfall and literature review. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(9):1109–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.130.9.1109.

Grogg KL, Lae ME, Kurtin PJ, Macon WR. Clusterin expression distinguishes follicular dendritic cell tumors from other dendritic cell neoplasms: report of a novel follicular dendritic cell marker and clinicopathologic data on 12 additional follicular dendritic cell tumors and 6 additional interdigitating dendritic cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(8):988–98. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pas.0000112536.76973.7f.

Domínguez-Malagón H, Cano-Valdez AM, Mosqueda-Taylor A, Hes O. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the pharyngeal region: histologic, cytologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of three cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2004;8(6):325–32. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.anndiagpath.2004.08.001.

Chou YY, How SW, Huang CH. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the soft palate. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104(11):843–7.

Bothra R, Pai PS, Chaturvedi P et al. Follicular dendritic cell tumour of tonsil—is it an under-diagnosed entity? Indian J Cancer. 2005;42(4):211–4.

Clement P, Saint-Blancard P, Minvielle F, Le Page P, Kossowski M. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsil: a case report. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27(3):207–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.09.003.

Aydin E, Ozluoglu LN, Demirhan B, Arikan U. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsil: case report. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263(12):1155–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-006-0124-9.

Shia J, Chen W, Tang LH et al. Extranodal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: clinical, pathologic, and histogenetic characteristics of an underrecognized disease entity. Virchows Arch. 2006;449(2):148–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-006-0231-4.

Fan YS, Ng WK, Chan A et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology in follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: a report of two cases. Acta Cytol. 2007;51(4):642–7. https://doi.org/10.1159/000325817.

McDuffie C, Lian TS, Thibodeaux J. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsil: a case report and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2007;86(4):234–5.

Vaideeswar P, George SM, Kane SV, Chaturvedi RA, Pandit SP. Extranodal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsil—case report of an epithelioid cell variant with osteoclastic giant cells. Pathol Res Pract. 2009;205(2):149–53.

Eun YG, Kim SW, Kwon KH. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsil. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51(4):602–4. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2010.51.4.602.

Suhail Z, Musani MA, Afaq S, Zafar A, Ahmed Ashrafi SK. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of tonsil. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20(1):55–6.

Li L, Shi YH, Guo ZJ et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis assessment of extranodal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(20):2504–19. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i20.2504.

Suchitha S, Sheeladevi CS, Sunila R, Manjunath GV. Extra nodal follicular dendritic cell tumor. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53(1):175–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/0377-4929.59224.

Mondal SK, Bera H, Bhattacharya B, Dewan K. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsil. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2012;3(1):62–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-5950.102165.

Kara T, Serinsoz E, Arpaci RB, Vayisoglu Y. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsil. BMJ Case Rep. 2013; https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-007440.

Hu T, Wang X, Yu C et al. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the pharyngeal region. Oncol Lett. 2013;5(5):1467–76. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2013.1224.

Vorsprach M, Kalinski T, Vorwerk U. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsil. Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211(1):88–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2014.09.015.

Horváth E, Mocan S, Chira L, Nagy EE, Turcu M. High-risk follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsil mimicking nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Pol J Pathol. 2015;66(4):430–3. https://doi.org/10.5114/pjp.2015.57262.

Kulkarni MP, Momin YA, Deshmukh BD, Sulhyan KR. Extranodal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma involving tonsil. Malays J Pathol. 2015;37(3):293–9.

Lu ZJ, Li J, Zhou SH et al. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the right tonsil: a case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(2):575–82. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2014.2726.

Amirtham U, Manohar V, Kamath MP et al. Clinicopathological profile and outcomes of follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the head and neck region - a study of 10 cases with literature review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(8):XC08-11. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/19763.8386.

Agaimy A, Michal M, Hadravsky L, Michal M. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: clinicopathologic study of 15 cases with emphasis on novel expression of MDM2, somatostatin receptor 2A, and PD-L1. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2016;23:21–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2016.05.003.

Pang J, Mydlarz WK, Gooi Z et al. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the head and neck: case report, literature review, and pooled analysis of 97 cases. Head Neck. 2016;38(1):E2241-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24115.

Pecorella I, Okello TR, Ciardi G, Ochola E, Ogwang MD. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the head and neck. Literature review and report of the tonsil occurrence in a Ugandan patient. Pathologica. 2017;109(2):120–5.

Wu B, Lim CM, Petersson F. Primary tonsillar epithelioid follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: report of a rare case mimicking undifferentiated carcinoma and a brief review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13(4):606–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-019-01015-3.

Lopez-Hisijos N, Omman R, Pambuccian S, Mirza K. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma or not? A series of 5 diagnostically challenging cases. Clin Med Insights Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179554919844531 (Published 2019 May 23).

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hutchison, B., Sadigh, S., Ferry, J.A. et al. Tonsillar p16-Positive Follicular Dendritic Cell Sarcoma Mimicking HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Case Report and Review of Reported Cases. Head and Neck Pathol 15, 267–274 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-020-01152-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-020-01152-0