Abstract

Background

Hypopharyngeal packs are used in nasal surgery to reduce the risk of aspiration and postoperative nausea and vomiting. Side effects associated with their use range from throat pain to retained packs postoperatively.

Aim

To evaluate, as a pilot study, postoperative nausea/vomiting and throat pain scores for patients undergoing nasal surgery in whom a wet or dry hypopharyngeal pack was placed compared with patients who received no packing.

Methods

A randomized, double-blind prospective trial in a general ENT unit.

Results

The study failed to show a statistically significant difference between the three groups in terms of their postoperative nausea/vomiting and throat pain scores at 2 and 6 h postoperatively. This is the first study in which dry packs have been compared with wet and absent packs.

Conclusion

Based on our findings, the authors recommend against placing hypopharyngeal packs for the purpose of preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a recognized complication of nasal surgery [1]. Potential causes may be related to patient factors, anaesthetic agents and opiate analgesia. Ingested blood is a potent emetic and may result in considerable postoperative patient morbidity and delayed discharge. Contrary to popular belief, a cuffed endotracheal tube is not 100% effective in preventing aspiration of hypopharyngeal blood [2].

Anaesthetists often place hypopharyngeal packs during nasal surgery, following intubation, in an attempt to prevent PONV. The packing is also thought to prevent the ingestion and aspiration of blood, cartilage and bone fragments. However, packing is not devoid of its own associated risks that include throat pain (TP), pharyngeal plexus trauma and oedema of the oro/hypopharynx [3–6]. There is also the potentially devastating complication of upper airway obstruction, if removal of the pack postoperatively was omitted [6].

To date there have been two prospective randomized studies evaluating the benefits or otherwise of hypopharyngeal packing. Basha et al. [7] compared the use of saline-soaked green ribbon gauze with no packing in 93 patients. They found that the pack had no effect on the incidence of PONV, but was associated with a significantly increased incidence of sore throat; additionally, an increased incidence of PONV in the absence of a pack was not identified. Piltcher et al. [8] evaluated 140 patients using two damp gauze swabs in the hypopharynx. This group found no difference related to PONV, throat pain and the use of anti-emetics between both groups.

No study has yet considered the effect, if any, of using a dry throat pack on the incidence of PONV and throat pain.

The aim of this pilot study was to assess, in a prospective randomized double-blind trial, the efficacy of preventing PONV using a dry and a wet hypopharyngeal pack and compare the results with patients who received no packing. The incidence of throat pain was also evaluated in those with wet, dry and absent hypopharyngeal packs.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CREC) of the Cork Teaching Hospitals and the South Infirmary and Victoria University Hospital. A randomized, prospective double-blind study was undertaken in the department of ENT in the South Infirmary and Victoria University Hospital, over a 10-month period from March to December 2007.

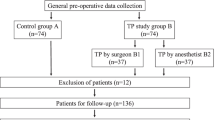

Fully informed, consented patients undergoing nasal surgery were recruited for the study by the first author. Patients were also randomly allocated into one of three groups by the first author; in the first group, the gauze packing was dry, in the second it was wet (saline soaked) and in the third it was absent. In generating an allocation sequence, a series of numbered envelopes containing information about one of the three possible allocations were created. For each patient, a numbered envelope was drawn out of a container. At induction, an anaesthetist opened the envelope to identify into which group the patient was allocated. Only the first author knew the allocation sequences and he was not involved in the visual analogue scoring postoperatively. Following endotracheal intubation, those who received the packing had two soft cotton gauze packs tied together inserted into the hypopharynx under direct vision using a McGill’s forceps. The packs were tied to the endotracheal tube and their placement was documented on the scrub nurse’s count board. Sleek tape was placed across the tube and “throat pack” was written on the tape as a further safety measure. The success of blinding was not evaluated.

All patients received a standardized anaesthetic regimen consisting of atracurium 0.5 mg/kg at induction. Anaesthesia was maintained using remifentanil 0.25 microg/kg/min and propofol 2–4 mg/kg, administered via a total intravenous anaesthesia delivery system. Intraoperatively, each patient intravenously received 4 mg of ondansetron, 2 g of paracetamol, 75 mg diclofenac and 100 mg of tramadol.

Patients were included if older than 18 years of age, had ASA 1 or 2, and if their surgery involved a septoplasty, rhinoplasty or endoscopic sinus surgery (±nasal polypectomy). Patients were excluded if active infection was present, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory contraindication existed, electrocautery was performed, additional procedures were carried out or intraoperative complications arose. PONV and throat pain scores at 2, 6 and 24 h postoperatively, as determined by patients on a 100 mm long visual analogue scale (VAS), were recorded by a junior surgeon who was unaware of the group allocation. This was the extent of their follow-up. Patients were also unaware as to the type or indeed presence of a pack during their surgery.

Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Kruskal–Wallis test. Statistical significance was identified if p < 0.05.

Results

Sixty patients consented to take part in our study. One patient developed a pneumothorax, two were intraoperatively found to have a purulent sinusitis and five patients had an additional submucosal diathermy to the inferior turbinate. Of the remaining 52 patients, the mean age was 39 years (range, 19–62 years). The ratio of males to females who took part in the study was approximately 4:1.

Sixteen patients were randomized to receive a wet hypopharyngeal pack, 20 received a dry pack and 16 had no packing administered. The median and interquartile ranges of pain and nausea/vomiting scores at 2 and 6 h are illustrated in Table 1.

No statistically significant difference emerged between the three groups on their PONV and throat pain scores at 2 and 6 h postoperatively (Table 2). In addition, no patients developed postoperative complications secondary to aspiration. No adverse events were reported from the use of the throat packs. Unfortunately, the number of patients who remained in hospital overnight following surgery was so small that it rendered statistical analysis of this group difficult.

Discussion

The use of hypopharyngeal packing is often undertaken by anaesthesiologists to prevent PONV, in the absence of good evidence of efficacy. To date, studies evaluating the role of hypopharyngeal packs have not considered dry packing and their possible effects. It seems plausible that dry packing may be more traumatic to the hypopharyngeal mucosa during placement, whilst having more room for absorbing blood than a wet pack. This is the first study to appraise the role of dry packing in a prospective, randomized trial.

Our pilot study identified no statistically significant benefit from using a wet or a dry pack over no pack in nasal surgery in preventing PONV and throat pain at 2 and 6 h postoperatively.

Whilst it would seem logical that hypopharyngeal packing facilitates the removal of bone or cartilaginous fragments following a septoplasty, preventing potentially catastrophic aspiration of this material, the effect of ingested blood inducing postoperative emesis may not be as clear-cut. A randomized trial evaluating PONV following tonsillectomy illustrated no benefit of stomach aspiration following tonsillectomy in preventing PONV. Perhaps, careful and detailed inspection and suctioning of the oro/hypopharynx may be most practical in the absence of packing. Furthermore, there is no evidence of cartilage aspiration following septoplasty in the literature. Endotracheal intubation alone is associated with TP postoperatively in 50% of patients [1]. The anaesthetic agents and anti-emetic and analgesic regimens were standardized for our population group.

It is noteworthy that because of the relatively small population size in this pilot sudy, and the overall low VAS grading measures for PONV and TP, the results were skewed, making statistical analysis more difficult. Other additional patient risk factors for PONV, including female gender, smoking habit and prior history of PONV, were not considered.

Based on our findings and other studies [7, 8], the authors recommend against placing either wet or dry hypopharyngeal packs for the purpose of preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting.

References

Marais J, Prescott RJ (1993) Throat pain and pharyngeal packing: a controlled randomized double-blind comparison between gauze and tampons. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 18:426–429

Seraj MA, Ankutse MM, Khna FM, Siddiqui N, Ziko AO (1991) Tracheal soiling with blood during intranasal surgery. Middle East J Anesthesiol 11:79–89

Conway CM, Miller JS, Sugden FLH (1960) Sore throat after anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 32:219–223

Mermer RW, Zwiilenberg D, Maron A, Brill CB (1990) Unilateral pharyngeal plexus injury following use of an oropharyngeal pack during third-molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 48:1102–1104

Kawaguchi M, Sakamoto T, Ohnishi H, Karasawa J (1995) Pharyngeal packs can cause massive swelling of the tongue after neurosurgical procedures. Anesthesiology 83:434–435

Najjar MF, Kimpson J (1995) A method for preventing throat pack retention. Anesth Analg 80:208–209

Basha SI, McCoy E, Ulla R, Kinsella JB (2006) Pharyngeal packing during routine nasal surgery. Anaesthesia 61:1161–1165

Piltcher O, Lavinsky M, Lavinsky J, de Oliveira Basso PR (2007) Effectiveness of hypopharyngeal packing during nasal and sinus surgery in the prevention of PONV. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 137(4):552–554

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fennessy, B.G., Mannion, S., Kinsella, J.B. et al. The benefits of hypopharyngeal packing in nasal surgery: a pilot study. Ir J Med Sci 180, 181–183 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-010-0601-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-010-0601-4