Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) has been gaining acceptance because it has shown good short- and mid-term results as a single procedure for morbid obesity. The aim of this study was to compare short- and mid-term results between laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) and LSG.

Methods

Observational retrospective study from a prospective database of patients undergoing LRYGB and LSG between 2004 and 2011, where 249 patients (mean age 44.7 years) were included. Patients were followed at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months, and annually thereafter. Short- and mid-term weight loss, comorbidity improvement or resolution, postoperative complications, re-interventions, and mortality were evaluated.

Results

One hundred thirty-five LRYGB and 114 LSG were included. Significant statistical differences between LRYGB and LSG were found in operative time (153 vs. 93 min. p < 0.001), minor postoperative complications (21.5 % vs. 4.4 %, p = 0.005), blood transfusions (8.8 % vs. 1.7 %, p = 0.015), and length of hospital stay (4 vs. 3 days, p < 0.001). There were no differences regarding major complications and re-interventions. There was no surgery-related mortality. The percentage of excess weight loss up to 4 years was similar in both groups (66 ± 13.7 vs. 65 ± 14.9 %). Both techniques showed similar results in comorbidities improvement or resolution at 1 year.

Conclusions

There is a similar short- and mid-term weight loss and 1-year comorbidity improvement or resolution between LRYGB and LSG, although minor complication rate is higher for LRYGB. Results of LSG as a single procedure need to be confirmed after a long-term follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the last decades, obesity has become a major health care concern. Moreover, obesity is related to different comorbidities as coronary heart disease, hypertension, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, muscular and joint pain, degenerative osteoarthritis, and depression. These comorbidities not only lead to a reduction in life expectancy, but also in quality of life [1]. Many different approaches (diets, exercise, and pharmacologic treatments) have been proposed to treat patients with morbid obesity but with a high failure rate, only bariatric surgery showed excellent short- and long-term results [2].

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) is currently considered the gold standard for morbid obesity; it is a restrictive and malabsorptive irreversible procedure, first reported by Wittgrove and Clark in 1994 [3]. It is a technically demanding procedure with a long learning curve and a considerable morbidity and mortality rate [4].

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is a restrictive procedure, although irreversible. First described by Hess [5] and Marceau [6] in 1988 as the first step before a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/ DS), then it was used in super-obese patients as the first step prior to other complex procedures [7]. However in 1993, Johnston et al. [8] proposed LSG as single procedure. Since then, LSG has gained popularity because it is considered a technically less complex procedure with satisfactory short-term results [2, 9]. Recent reports recommend LSG as a definitive treatment for morbid obesity with good results in excess weight loss and a favorable impact on comorbidities [10].

The aim of this study was to compare the short- and mid-term results in obese patients who underwent LRYGB versus LSG. The primary endpoint was weight loss. Secondary endpoints were short- and long-term complication rates, length of hospital stay, need for re-operation, and efficiency of the procedures inducing resolution of comorbidities.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection Process

This is an observational retrospective study from a prospective database in which all patients that were operated between January 2004 and October 2011 at Hospital Universitario del Mar in Barcelona, Spain, for obesity surgery were included.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria are age between 18 and 60 years and fulfillment of the 1991 National Institutes of Health bariatric surgery criteria [11].

Exclusion Criteria

Patients younger than 18 and older than 60 years, history of alcohol or drug dependence, patients that did not complete the preoperative evaluation, and patients with psychiatric diseases that were considered not suitable by our psychiatry group were not included.

Patients were evaluated and followed pre- and perioperatively by a multidisciplinary team (surgeons, endocrinologist, psychologist, psychiatrist, dietitians, and anesthesiologist). Candidates for surgery were informed about the procedure and all completed an extensive preoperative work-up indicated by the multidisciplinary group.

Indication for LRYGB or LSG was based on clinical criteria and the consensus of the bariatric surgery unit. During the first 2 years of our experience, all patients underwent LRYGB technique. Since 2006, LSG was also performed.

Patients with a body mass index (BMI) between 40 and 50 kg/m2 underwent LRYGB, while in patients with any of the following criteria such as BMI > 50 kg/m2, BMI between 35 and 40 kg/m2 with major comorbidities, renal transplant recipients who require immunosuppressive drugs, patients with continuous use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), patients with inflammatory bowel disease and for patients under 25 or over 55 years, LSG was indicated. Severe gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus was an exclusion criteria for LSG.

All patients were informed in detail about the risk and benefits of each technique and signed the written informed consent.

The efficacy was assessed using the percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL), calculated as 100 % × [preoperative weight-postoperative weight] / excess preoperative weight, and resolution or improvement of comorbidities. Safety was considered in terms of early (<30 days) and late (>30 days) postoperative surgical complications (classified using Clavien score) [12] and their treatment, procedure-related mortality, and mortality by other causes. Clavien grades I and II were considered as minor complications whereas Clavien grades III, IV, and V were considered as major complications.

Operative Technique

All the operations were primarily attempted laparoscopically by the same surgical team.

The LRYGB technique included in all cases an antecolic and antegastric LRYGB with an alimentary limb of 150 cm and a biliopancreatic limb of 50 cm. A 20–30 cm3. vertical gastric pouch was created using a stapling device (Endo-GIA ®, US Surgical Corporation, Norwalk, CT, USA). An end-to-side gastro-jejunostomy (GJ) was performed using a 25-mm circular stapler (DST series PCEEA, Autosuture; Covidien Norwalk, CT, USA). A side-to-side jejuno-jejunostomy was created using a 60-mm-diameter lineal stapler with white loads (Endo-GIA ®, US Surgical Corporation, Norwalk, CT, USA). A methylene blue test was always performed to identify possible leaks. A closed suction drain was placed in the proximity of the GJ.

In the LSG group, the gastrosplenic omentum was divided from the greater curvature close to the stomach wall using Ultracision® (Ethicon EndoSurgery, Somerville, NJ, USA). This dissection was started 5 cm proximally from the pylorus. The left crus of the diaphragm was completely dissected and clearly visualized. The angle of His was fully mobilized. Posterior adhesions to the pancreas were taken down. The gastric tube was created over a 36-F bougie using multiple firings of a stapler (Endo-GIA ®, US Surgical Corporation, Norwalk, CT, USA). Buttress material was used for staple line reinforcement (Seamguard® staple line reinforcement material, W.L. Gore &Associates, Ariz, USA). A methylene blue test was performed to check for leaks and a closed suction drain was placed along the length of the gastric staple line.

Perioperative Care

Patients received 2 g of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid preoperatively. Low molecular weight heparin was administered subcutaneous daily, and sequential compression devices were used. According to our protocol, patients were given clear liquids and started sitting in a chair on the first postoperative day (POD 1), and advance to a full-liquid diet and walking on the second postoperative day. Patients were routinely discharged to home on the third postoperative day, after removal of the closed suction drain. A nutritionist met with all patients on POD 1.

Postoperative follow-up was evaluated by the multidisciplinary team (surgeon, endocrinologist, and dietitian) at 7 days, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months, and every year thereafter. After the operation, both groups received daily acid suppression medication with pantoprazole and multivitamin and mineral supplementation systematically for the first 12 months. All patients undergoing LRYGB received vitamin B12 supplementation. Vitamin D and iron supplements were given depending of the blood test controls. Discontinuation of medical therapy was considered in cases of blood pressure control and lipids or glucose normalization.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were described with frequencies and percentages. Quantitative variables were expressed with mean and standard deviation if normally distributed and with median plus interquartile range (IQR) (25th–75th percentile) otherwise. Chi-square test or Fisher exact test were used as appropriate to compare proportions between LRYGB and LSG groups. Student’s t test for independent samples was used to assess differences of quantitative variables. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using statistical package for Social Sciences version 18.0 (SSPS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 249 consecutive patients operated for morbid obesity were included in the study. One hundred and thirty-five (54.2 %) underwent LRYGB and 114 (45.8 %) LSG, with a median (IQR) follow-up of 24 (12–36) months. The demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1. A statistically significant difference in BMI was observed between both groups related to the inclusion criteria, because 54.4 % of patients in the LSG group had a preoperatively BMI equal or less than 40 kg/m2 compared to 8.1 % in the LRYGB group.

Patient compliance with their scheduled follow-up visit for both procedures was 100 % at 3 months, 99 % at 6 months, 97 % at 12 months, 94 % at 18 months, 90 % at 2 years, 86 % at 3 years, and 80 % at 4 years.

Comorbidities

Major comorbidities in the whole group were dyslipidemia (54.6 %), hypertension (35.34 %), arthropathy (30.9 %), obstructive sleep apnea (27.7 %), diabetes mellitus (25.3 %), and ischemic heart disease (5.6 %), while minor comorbidities were urinary stress incontinence in women (53.7 %), depression (47.8 %), and infertility in women (8.4 %). Demographic data and comorbidities in the two study groups are shown in Table 1. Except of obstructive sleep apnea and depression, both groups are similar.

Early Surgical Results

There was no surgery-related mortality. One patient in the LSG group died 60 days after surgery because of myocardial infarction that occurred 2 days after the procedure.

All procedures were done laparoscopically but five (2 %) conversions to open surgery were needed, three in the LRYGB, and two in the LSG group. The mean operative time for LYRGB was 153 min (90–300 min) while for LSG was 93 min (40–192 min), p < 0.001.

According to Clavien classification, a total of 34 patients with minor complications (I–II) were identified, 29 (21.5 %) in the LRYGB, and 5 (4.4 %) in the LSG group (p = 0.005). Thirteen patients (5.2 %) developed major complications (IIIa, IIIb, IV, and V), 8 (5.9 %) in the LRYGB, and 5 (4.4 %) in the LSG group (p = NS). Early minor and major surgical complications are detailed in Table 2.

Only six patients (4.4 %) in the LRYGB and four (3.5 %) in the LSG group required re-operation (p = 0.758). The causes of re-intervention in the LRYGB were: ileal perforation in one case, port-site bleeding in two, hemoperitoneum of unknown origin in one, umbilical strangulated hernia in one, and gastric remnant leak treated with partial gastrectomy in one. In the LSG group, there was port-site bleeding in two cases and gastric leak in two, one treated by restapling the leak site and the second by placing an abdominal drain. Fourteen patients (5.6 %) presented bleeding after the operation and needed blood transfusion, 12 (8.8 %) in the LRYGB and 2 (1.7 %) in LSG group (p = 0.015). Only three patients (2.3 %) in the LRYGB and two (1.7 %) in the LSG required re-operation because of bleeding. The remaining bleeding cases (n = 9) in the LRYGB group were treated conservatively with blood transfusions. Median length of hospital stay was 4 days (3–104 days) for LRYGB and 3 days (3–61 days) for LSG patients, p < 0.001.

Four patients required readmission during the first 30 days after surgery, three (2.2 %) in the LRYGB (fever from undetermined cause, hematoma of the remnant stomach, and small gastric fistula) and one (0.9 %) in the LSG group (one subphrenic abscess; p = NS). All patients were treated conservatively.

Late Surgical Results

During follow-up, there were 21 surgical interventions, 18 in the LRYGB (13.3 %) and 3 (2.6 %) in LSG group (p <0.001). Table 3 details the causes of surgical interventions in both groups.

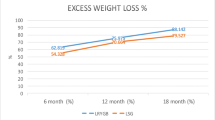

Clinical Outcome: Weight Loss

The percentage of weight loss was similar when comparing both surgical techniques as depicted in Fig. 1. Only at 3 months, there was a significant difference in mean percentage of excess weight loss between LRYGB and LSG (45 vs. 48 %, p = 0.034). When patients with more than 50 % of %EWL were analyzed, there were no differences between LRYGB and LSG at 1 year (95.4 vs. 90.8 %) and 4 years (90.4 vs. 80 %). Similarly, although a significant difference in BMI was observed between LRYGB and LSG before and at 3 and 6 postoperative months, this difference disappeared after 12 months (Fig. 2).

Clinical Outcome: Resolution or Improvement of Comorbidities

A considerable improvement or resolution rate of comorbidities was observed at 1 year postoperatively. The resolution of comorbidities of the whole group was hypertension 71.6 %, diabetes mellitus 93.6 %, dyslipidemia 64 %, obstructive sleep apnea 92.1 %, urinary effort incontinence 89.8 %, and depression 70.6 %. Out of depression, no differences were observed between the study groups in comorbidities improvement or resolution. In Fig. 3, a detailed description of comorbidity improvement or resolution by groups is shown.

Discussion

In this study, both LSG and LRYGB were safe and effective bariatric procedures resulting in significant weight loss and favorable effects on comorbidities. LSG is technically less complex that that with the LRYGB, which is reflected by a lower operative time (153 min LRYGB vs. 93 min LSG, p < 0.001) and shorter length of stay (4 vs. 3 days in LRYGB and LSG, respectively; p > 0.001). It should be noted that we analyzed all patients operated on, including our first patients in our learning curve, and this may had a direct influence in the mean operative times.

With respect to %EWL, a %EWL over 65 % with both techniques 4 years after surgery can be obtained, without significant differences between LRYGB and LSG. Results available in the literature showed a wide range of %EWL from 33 to 83 % [4, 13–15]. Possible explanations are the differences in the study designs (series, comparative cohorts, randomized controlled trial, etc.) and, most important, discrepancies in the follow-up of patients [16–18]. In our study, more than 80 % of patients were followed for at least 4 years.

When only patients who achieved a EWL >50 % was considered, differences in the percentage of patients between both techniques were not observed, although at 4 years, a higher percentage of patients was found in the LRYGB group (90.4 vs. 80 %), confirming data provided by other authors suggesting that weight regain is higher in patients undergoing LSG [19].

Some factors have been proposed to have influence in the %EWL in LSG. Bougie sizes ranging from 32 to 60 F have been studied, but not direct correlation with %EWL has been demonstrated [20]. The distance from the pylorus to the beginning of the gastric transection and the complete resection of the fundus responsible for the ghrelin secretion have been also proposed as factors influencing the results. However, there was no broad agreement on these technical aspects. In our study, the same maneuvers were used in all patients: a 36-F bougie, 5 cm from the pylorus to the initiation of gastric transection, and the complete resection of the fundus. We take especially care in the dissection of the left crus, the identification of the fat pad and the dissection of the posterior attachments from the stomach to the pancreas to facilitate the complete resection of the fundus and avoid any remnant that may cause failure as has been suggested by several authors [21, 22]. Perhaps this combination may account for the excellent results obtained with LSG.

Although most of the data available suggest that morbidity related to LSG is lower than in LRYGB, results show a great disparity [4, 9, 10, 23, 24]. Our results confirm that morbidity is significantly lower in patients undergoing LSG, although these figures are related to a higher number of minor complications (20 vs. 3.5 %) but not to the incidence of major complications (5.9 vs. 4.4 %). Six gastric leaks were observed in the whole series (3 [2.2 %] in the LRYGB group and 3 [2.9 %] in the LSG). All leaks in the LRYGB were treated by conservative measures (endoscopic or medical) whereas two in the LSG needed surgery. As expected, morbidity prolonged hospital stay in our study, but had no influence in the mortality rate.

Nine patients required re-intervention [6 (4.4 %) of the LRYGB group and three (3.5 %) of the LSG group]. Hemorrhage was the cause of 50 % of the revisions in our series, mostly due to port-site bleeding. Since 2008, our policy is to systematically close all 10-mm port-sites and in the last 161 cases we have not needed any further re-operation for this reason. Also, we recently started using stapler reinforcement with buttress material.

There was no mortality directly related to the surgical procedure and the readmission rate was lower than in other studies [25] with no differences between LRYGB and LSG. As with others [26, 27], we showed an improvement of comorbidities that may become higher than 95 % in diabetes mellitus or obstructive sleep apnea. There are few data in the literature [10, 28, 29] comparing results between LRYGB and LSG, but the present data confirm similar improvement rate with both surgical techniques.

Regarding the metabolic profiles, the impact of LRYGB is well-known but few data are available with LSG. A previous report of our group demonstrates that LRYGB and LSG markedly improved glucose homeostasis [30]. LSG decreased fasting and postprandial ghrelin levels, whereas GLP-1 and PYY levels increased similarly after both procedures. Reduced ghrelin levels after LSG could be responsible of the weight-reducing effect LSG [30]. Moreover, we also demonstrated that bariatric surgery reduces 50 % the estimated cardiovascular risk at 1 year after surgery and that LSG is equally effective as LRYGB except for cholesterol metabolism [31, 32].

Some limitation of the study should be mentioned. This is a retrospective study although it is based on a prospective database and all patients were treated by the same surgical team. Secondly, the results are obtained from a comparison of two cohorts with some selection bias based on BMI. Finally, our follow-up is limited. Further randomized controlled studies are needed to elucidate long-term results, especially on the efficacy of the LSG as definitive bariatric procedure and to light up for mechanisms responsible of the success or failure in weight control and comorbidities resolution.

In conclusion, both LRYGB and LSG are safe procedures that provide excellent results in weight control and resolution of comorbidities in patients with morbid obesity.

References

Franco JV, Ruiz PA, Palermo M, et al. A review of studies comparing three laparoscopic procedures in bariatric surgery: sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1458–68.

Daskalakis M, Weiner RA. Sleeve gastrectomy as a single-stage bariatric operation: indications and limitations. Obes Facts. 2009;2 Suppl 1:8–10.

Wittgrove AC, Clark GW, Tremblay LJ. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y: preliminary report of five cases. Obes Surg. 1994;4:353–7.

Leyba JL, Aulestia SN, Llopis SN. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for the treatment of morbid obesity. A prospective study of 117 patients. Obes Surg. 2011;21:212–6.

Hess DS, Hess DW. Biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch. Obes Surg. 1998;8:267–82.

Marceau P, Hould FS, Simard S, et al. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. World J Surg. 1998;22:947–54.

Chowbey PK, Dhawan K, Khullar R, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: an Indian experience-surgical technique and early results. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1340–7.

Johnston D, Dachtler J, Sue-Ling HM, et al. The Magenstrasse and Mill operation for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2003;13:10–6.

Topart P, Becouarn G, Ritz P. Comparative early outcomes of three laparoscopic bariatric procedures: sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:250–4.

Lakdawala MA, Bhasker A, Mulchandani D, et al. Comparison between the results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the Indian population: a retrospective 1 year study. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1–6.

Hubbard VS, Hall WH. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Obes Surg. 1991;1:257–65.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13.

Boza C, Gamboa C, Salinas J, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a case-control study and 3 years of follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:243–9.

Abu-Jaish W, Rosenthal RJ. Sleeve gastrectomy: a new surgical approach for morbid obesity. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;4:101–19.

Bellanger DE, Greenway FL. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, 529 cases without a leak: short-term results and technical considerations. Obes Surg. 2011;21:146–50.

Srinivasa S, Hill LS, Sammour T, et al. Early and mid-term outcomes of single-stage laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1484–90.

Himpens J, Dobbeleir J, Peeters G. Long-term results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for obesity. Ann Surg. 2010;252:319–24.

Sarela AI, Dexter SP, O’Kane M, et al. Long-term follow-up after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: 8-9-year results. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:679–87.

Barhouch AS, Zardo M, Padoin AV, et al. Excess weight loss variation in late postoperative period of gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1479–83.

Papailiou J, Albanopoulos K, Toutouzas KG, et al. Morbid obesity and sleeve gastrectomy: how does it work? Obes Surg. 2010;20:1448–55.

Pech N, Meyer F, Lippert H, et al. Complications and nutrient deficiencies two years after sleeve gastrectomy. BMC Surg. 2012;12:13.

Braghetto I, Cortes C, Herquinigo D, et al. Evaluation of the radiological gastric capacity and evolution of the BMI 2–3 years after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1262–9.

Kehagias I, Karamanakos SN, Argentou M, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for the management of patients with BMI < 50 kg/m2. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1650–6.

Lee CM, Cirangle PT, Jossart GH. Vertical gastrectomy for morbid obesity in 216 patients: report of two-year results. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1810–6.

Hutter MM, Schirmer BD, Jones DB, et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Ann Surg. 2011;254:410–20. discussion 420–412.

Cottam D, Qureshi FG, Mattar SG, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as an initial weight-loss procedure for high-risk patients with morbid obesity. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:859–63.

Welch G, Wesolowski C, Zagarins S, et al. Evaluation of clinical outcomes for gastric bypass surgery: results from a comprehensive follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2011;21:18–28.

Helmio M, Victorzon M, Ovaska J, et al. SLEEVEPASS: A randomized prospective multicenter study comparing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass in the treatment of morbid obesity: preliminary results. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2521–6.

Chouillard EK, Karaa A, Elkhoury M, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: case-control study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:500–5.

Ramon JM, Salvans S, Crous X, et al. Effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy on glucose and gut hormones: a prospective randomised trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1116–22.

Benaiges D, Goday A, Ramon JM, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic gastric bypass are equally effective for reduction of cardiovascular risk in severely obese patients at one year of follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:575–80.

Benaiges D, Flores-Le-Roux JA, Pedro-Botet J, et al. Impact of restrictive (sleeve gastrectomy) vs hybrid bariatric surgery (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) on lipid profile. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1268–75.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Sergi Mojal, Statistics Unit, IMIM (Institut Hospital del Mar d’Investigacions Mèdiques), for expert help in the statistical analysis. We also thank Marta Pulido, MD, for editorial assistance.

Conflict of Interest

Pablo Vidal, José M Ramón, Albert Goday, David Benaiges, Lourdes Trillo, Alejandra Parri, Susana González, Manuel Pera, and Luís Grande declare no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vidal, P., Ramón, J.M., Goday, A. et al. Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass Versus Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy as a Definitive Surgical Procedure for Morbid Obesity. Mid-Term Results. OBES SURG 23, 292–299 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0828-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0828-4