Abstract

Summary

Osteoporotic hip fractures are thought to be rare in Blacks however, this study from South Africa shows a significant increase in the number of hip fracture in Blacks. With the expected increase in older people, osteoporotic fractures will pose a major health problem and screening guidelines needed to be implemented.

Introduction

Developing countries are predicted to bear the burden of osteoporosis in the coming decades. This study was undertaken to review earlier reports that osteoporotic hip fractures are rare in Black Africans.

Methods

In an observational study, the incidence rates and relative risk ratios (RRR) of osteoporotic hip fractures were calculated in the Black population, aged 60 years and older, residing in the eThekwini region of South Africa. All Black subjects, presenting with a minimal trauma hip fracture to five public hospitals in the region, entered the study. Descriptive statistics were applied to show differences in age and sex.

Results

Eighty-seven subjects were enrolled in the study with a mean age of 76.5 ± 10.5 years and the sex ratio of women to men was 2.5:1. Although men were younger than women, this was not significant (74.2 ± 12.3 vs. 77.4 ± 9.6 years, p = 0.189). The age-adjusted rate was 69.2 per 100,000 p.a. for women and 73.1 per 100,000 p.a. for men. There was a significant increase in the relative risk ratios for hip fractures after the age of 75 years in the total cohort and in women and men. Except for the 65–69-year age group, there was no significant difference in the age-adjusted RRR between women and men.

Conclusion

This study represents the largest number of hip fractures recorded in Black Africans. Although the incidence rate is approximately tenfold higher than previously recorded, it remains amongst the lowest globally. A national registry inclusive of private and public sector is required to establish the true incidence rate of hip fractures in Black Africans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The incidence of osteoporotic hip fractures is set to rise exponentially with the worldwide increase in longevity [1]. It is predicted that by 2050 there will be 4.5 million hip fractures per annum globally, and that the majority of these will occur in developing countries [2].

In a recent systematic review, a wide geographic variation in the incidence and probability of hip fractures was observed with the highest incidence rates in Denmark, Sweden, and Austria and lowest rates in South Africa and Nigeria, 5.6 and 2 per 100,000, respectively [3].

The South African average annual hip fracture rate of 5.6 per 100,000 (6.9 for men and 4.3 for women) is derived from a single study conducted between 1957 and 1963 in African men and women living in the Johannesburg metropolitan area. A total of 64 hip fractures (38 in men and 26 in women), excluding pathological fractures, but including all degrees of trauma, were recorded in persons aged 30 years and older in the study period [4]. The reason for this significantly low rate was not well understood, as a subsequent study in the same time period failed to show any significant difference in metacarpal BMD between Africans and Whites [5].

Similarly, the Nigerian data was obtained from a single regional study in 1988–1989 which included all subjects, aged 50 years and older, with hip fractures requiring hospital care. Only five hip fractures were recorded, giving an incidence of 2.1 per 100,000 in men and 2.0 per 100,000 in women, significantly lower than that in Southampton (UK). Furthermore there was no increase with age [6].

Low incidence rates have also been reported in two earlier studies in sub-Saharan Africa. In Gambia, no hip fractures were noted [7] and incidence rates of 4.1 per 100,000 and 2.2 per 100,000 for women and men respectively, were reported in a retrospective study in Cameroon [8]. A lower life expectancy and possible under-reporting [6, 8,9,10] have been postulated for these low rates.

More recent studies suggest that the incidence of osteoporotic fractures may be increasing [11]. A second study from Nigeria reported nine and fivefold increases in the incidence rates in women (17.3 per 100,000) and men (10.0 per 100,000), respectively, with the highest rates seen in women and men over the age of 80 years [12].

Although there have been no new studies on hip fractures in South Africa, two studies indicate that vertebral fractures may occur more commonly in Africans than previously thought [13, 14]. In a 5-year longitudinal study, 38% of African women aged 60 years or over developed new vertebral deformities [13] and a similar prevalence of vertebral fractures in African and White subjects has recently been reported [15].

These findings, together with the projected increase in life expectancy in Africa, [1] and significant urbanization support the notion that the incidence of osteoporotic fracture rates in developing countries such as South Africa is on the rise and prompted this study.

Methods

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of University of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), and study approval was obtained from the KZN Provincial Department of Health and from all the hospitals involved in the study. The study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines and principles of the International Declaration of Helsinki and South African Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

The study was conducted in the coastal city of eThekwini (formerly known as Durban), which is the largest city in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and has a mixed ethnic population of 3,468,087 persons, of whom 236,035 persons (6.8%) are above the age of 60 years old. The study population comprised the 108,240 (male 33,811, female 74,429) Black African subjects residing in the study area (Consensus Stats South Africa 2007) [16].

Although South Africa has a dual health care system with both a public (free for indigent and older patients) and private sector (fee based), the majority of African patients utilize the public sector with only 6.9% having a medical aid (insurance) [17], usually a pre-requisite for private health care. In the public sector, specialized orthopedic services are only available in five public regional hospitals serving the eThekwini area, to which all hip fracture subjects presenting to any public sector health care facility are referred.

A prospective observational study was conducted in these five regional hospitals from 1 August 2010 to 15 October 2011. Hip fracture cases were identified from the orthopedic admission registers on a bi-weekly basis and confirmed clinically and radiologically. All Black African subjects aged 60 years or over with a minimal trauma hip, neck of femur, or trochanteric fracture (defined as a fracture of the femur between the articular cartilage of the hip joint to 5 cm below the distal point of the lesser trochanter subsequent to a fall from a standing height or less) were entered into the study. Subjects were recorded at the site where the primary surgery occurred and all entries were cross-referenced with date of birth to prevent duplication. Subjects with pathological fractures, fractures distal to the lesser trochanter, traumatic fractures, and re-admissions for previous hip fracture complications were excluded. A structured questionnaire was used to record age, sex, and race (self-reported).

The data was analyzed using IBM® SPSS®19 and SAS® version 21. The significance for all tests was set at p < 0.05. Descriptive statistics were applied to show differences in age and sex. Differences in means were compared using Student’s t test for numerical variables.

The crude and age-specific hip fracture incidence rates for the eThekwini municipality and South Africa were first calculated using the total ethnic African population, aged 60 years or over, of eThekwini and South Africa, obtained from the 2007 census data [18]. The direct method (actual number of fractures divided by at risk population) was used to calculate age-specific rates (ASR) based on the age and sex structure of the ethnic African population of eThekwini.

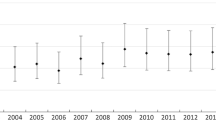

The relative risk ratio of fracture with 95% confidence intervals was calculated for each age group (5-year intervals) using the 60–64-year age group as the reference group. A linear regression model was fitted with relative risk ratios as the dependent variable, age as an independent variable, and sex as an indicator variable to determine if a significant difference existed between the sexes.

Results

Eighty-seven Black African subjects with minimal trauma hip fractures were admitted during the study period. They were 62 (71.3%) women and 25 (28.7%) men with a female to male ratio of 2.5:1. The mean age was 76.5 ± 10.5 years with a range of 60 to 113 years. Although men were younger than women (74.2 ± 12.3 vs. 77.4 ± 9.6 years), there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.189).

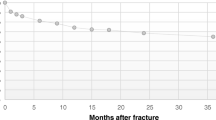

The number of fractures increased with age and the highest number were recorded in subjects older than 85 years.

The crude incidence rate for minimal trauma hip fractures was 67.4 per 100,000 (Table 1) with an age-adjusted rate of 77.1 per 100,000 persons per annum. The incidence increased with age with the highest hip fracture rate recorded in subjects aged 85 years and older (305.8 per 100,000). The ASR increased with age in the South Africa population, except in the 80–84-year age group. There was a significant increase in the relative risk ratio for hip fracture with age after the age of 75 years in both women and men (Table 2).

The overall age-adjusted fracture incidence rate was higher in men (73.1 per 100,000) compared to women (69.2 per 100,000), with the highest rates in 85 years and older group in both sexes. Apart from in the 65–69-year age group (RR 0.18, CI 0.04–0.71), no significant sex difference was observed for the age-adjusted relative risk ratios in men and women (Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first study to report osteoporotic hip fractures in an older Black African population in post-apartheid South Africa. To our knowledge, this also represents the largest number of Black African subjects with hip fractures in sub-Saharan Africa.

The main finding of this study is the significant increase in the incidence of osteoporotic hip fractures in Black Africans. The crude rate of 67.4 per 100,000 is 12-fold higher than previously reported [4] and although the highest reported in SSA remains within the low risk category and among the lowest globally [3]. This crude incidence rate, however, may still be an under estimation due to the exclusion of subjects using private health care facilities and those that may have not sought medical care. In accordance with other studies, an age-related increase in hip fracture rates was noted, with an almost tenfold increase in subjects over 85 years compared to those in the 60–65-years age group.

Several reasons may contribute to the increased incidence rate, including an increase in life expectancy, urbanization, and a change in dietary and lifestyle factors. Advancing age is well established as a strong risk factor for osteoporosis and an independent risk factor for hip fractures [16, 19]. It is, therefore, not surprising that countries with high LE, such as Norway and Sweden, where the LE is over 80 years, have a high incidence of hip fractures [3].

Compared to the global average of a LE of 71.4 years in 2015, that for South Africa is very modest at 62.9 years [20]. This, however, needs to be viewed in context of the demographic changes over the past few decades. From 1960, when the Solomon study was undertaken, the average LE in South Africa rose from 49 to 62.1 years by 2000, but then fell to 51.6 years in 2005, largely due to the high adult mortality from the HIV/AIDS epidemic [21]. With the widespread introduction of anti-retroviral therapy and other advances in health care, the LE is now again over 60 years. Accompanying this rise, the proportion of older persons has increased from 6.66% in 2002 to 8.01% and it is predicted that by the year 2050, 24.3% of the country’s population will be older than 60 years [1].

The lower mean age at fracture of 76.5 years compared to that in Europe and USA [22, 23], may also be a reflection of the lower LE and smaller proportion of older adults. In contrast, the mean age at fracture is higher than that reported from other developing countries such as India, Latin America, and the rest of Africa, where the mean age is usually less than 75 years [10, 24, 25]. The reasons for this are not clear and may include differences in LE, genetic and environmental factors, and differences in health care.

The traditional view that men fracture at an older age, largely due to their higher bone mass and lower fall risk [26, 27], has been questioned. In a recent literature review, men were younger from 3 to 6 years in the majority of studies [28]. Factors contributing to the younger age at hip fractures in men include higher burden of comorbidities [29], higher likelihood of secondary causes [30], higher mortality rate throughout the lifespan from all causes including hip fractures, and perhaps the lack of therapeutic and prophylactic interventions [31]. In keeping with this trend, men were younger, albeit not significantly, in this study.

While there is also a significant shift in the sex ratio from a male predominance reported by Solomon (male:female = 1.5:1) to a female predominance of 2.5:1 in this study, similar to developed countries, where 70–75% of hip fracture occur in women [32], the age-adjusted rate in men was higher. With the change in apartheid laws, which restricted access of Black Africans, and especially women, into city centers, a shift in the sex ratio is expected [33]. The significant lower proportion of men in the population aged 60 years or over, 31.2 and 34.6% in eThekwini and South Africa, respectively, may account for the higher incidence rates in men. Secondary causes such as alcohol may also play a role. Excessive alcohol consumption, a known risk factor for osteoporosis, is significantly more common in men compared to women in South Africa [34].

Studies in other developing countries including in Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand [35], Nigeria [12], and Morocco [10] have also seen a change in sex ratio with a higher increase in the fracture risk in women than in men. In contrast, recent studies from the Indian subcontinent have observed only a slight increase in women compared to men [25, 36] and the sex ratio in African Americans remains unchanged and much lower at 1.5:1 [28].

Urban migration may have also contributed to the increase in incidence of hip fractures in this study. Following the repeal of restrictive legislation limiting free movement, large numbers of people have moved into urban and peri-urban areas seeking for employment and other opportunities and or moving closer to family and facilities. The significant increase in the population in this study region, by well over half a million persons since 2001, is thought to be largely due to urban migration.

The higher incidence of hip fractures reported in urban versus rural communities in several populations [19, 35, 37, 38] has been attributed to several factors including decreased physical activity [39], lower vitamin D levels, increase in trauma [40], and lifestyle factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption [41] but not due to the location of institutions [42]. While the majority of studies in a systematic review [43] confirmed a lower incidence of hip fractures in rural populations, a few did not.

Although still amongst the lowest globally, the incidence rate in this study is higher than in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa. Possible reasons include differences in genetic, demographic, environmental, and cultural and lifestyle factors as well as a lack of awareness and under-reporting. Recent studies suggest that fracture rates in Africa are increasing, possibly due to increasing LE, low calcium intake, multiple pregnancies, prolonged breastfeeding, decreasing physical activity levels, and increasing urbanization in developing countries [8, 10]. More important, however, are the reports of under treatment and poor outcome in African patients with fragility fractures.

Limitations

In the absence of a hip fracture registry, this study was undertaken in the public hospital sector of eThekwini which the majority of older African subjects in South Africa access [44]. The incidence rates may have been under estimated, as the study might have missed subjects admitted to the private sector or those who did not seek health care. Care was taken to verify that subjects resided in the study area and double counting was avoided by using personal identifiers, making over-estimation less likely.

Conclusion

This study provides an important update in the incidence of osteoporotic hip fractures in Black South Africans. The increased incidence rates in both men and women and the younger age at fracture, especially in men, have important implications for screening and treatment guidelines. The current recommendation of the National Osteoporosis Foundation of South Africa (NOFSA) guidelines to measure BMD density in men at age 70 years [45] may need to be re-considered, especially in African men.

This study highlights the need for further national studies to determine the incidence of hip fractures in the multi-ethnic population of South Africa.

References

Fuleihan G. The Middle East and Africa Audit (2011) International Osteoporosis Foundation. Available online at https://www.aub.edu.lb/fm/cmop/downloads/ME_audit-e.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2016

Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA (1997) World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 7(5):407–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00004148

Kanis JA, Oden A, McCloskey EV et al (2012) A systematic review of hip fracture incidence and probability of fracture worldwide. Osteoporos Int 23(9):2239–2256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-1964-3

Solomon L (1968) Osteoporosis and fracture of the femoral neck in South African Bantu Blacks. J Bone Joint Surg 36(50B):2–1

Solomon L (1979) Bone density in ageing Caucasians and African populations. Lancet 2(8156–8157):1326–1330

Adebajo AO, Cooper C, Evans JG (1991) Fractures of the hip and distal forearm in West Africa and the United Kingdom. Age Ageing 20(6):435–438. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/20.6.435

Asprey TJ, Prentice A, Cole TJ et al (1996) Low bone mineral content is common but osteoporotic fractures are rare in elderly rural Gambian women. J Bone Miner Res 11(7):1019–1025

Zebaze RMD, Seeman E (2003) Epidemiology of hip and wrist fractures in Cameroon. Africa Osteoporos Int 14(4):301–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-002-1356-1

Maalouf G, Gannag’e-Yared MH, Ezzedine J et al (2007) Middle East and North Africa consensus on osteoporosis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 7(2):131–143

El Maghraoui A, Ngbanda AR, Bensaoud N, Bensaoud M, Rezqi A, Tazi MA (2013) Age-adjusted incidence rates of hip fractures between 2006 and 2009 in Rabat. Morocco Osteoporos Int 24(4):1267–1273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2061-3

El Maghraoui A, Loumba BA, Jroundi I et al (2005) Epidemiology of hip fractures in 2002 in Rabat. Morocco Osteoporos Int 16(6):597–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-004-1729-8

Jervas E, Onwukamuche CK, Anyanwu GE, Ugochukwu AI (2011) Incidence of fall related hip fractures among the elderly persons in Owerri, Nigeria. Asian J Med Sci 3(3):110–114

Basu D (2010) Determination of bone mass and prevalence of vertebral deformities in postmenopausal black women in South Africa. PhD dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

Conradie M, Conradie MM, Kidd M, Hough S (2014) Bone density in black and white South African women: contribution of ethnicity, body weight and lifestyle. Arch Osteoporos 9(1):193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-014-0193-0

Conradie M (2008) A comparative study of known determinants of bone strength in black and white South African females, in Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, PhD dissertation, Tygerberg Academic Hospital. University of Stellenbosch

Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, Cauley J, Black D, Vogt TM (1995) Risk factors for hip fractures in white women. Study of osteoporotic fractures research group. N Engl J Med 332(12):767–773. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199503233321202

Statistics South Africa, General Household Survey 2007–2008. Available online at www.gov.za/documents/download.php. Accessed 10 May 2017

Statistics South Africa (2008) Available online at https://statssa.gov/za/publications/P03011/p03011007.pdf, 2008. Accessed 10 May 2017

Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ 3rd (1992) Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int 2(6):285–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01623184

World Health statistics, Life expectancy at birth (years) 2000–2015, Global health Organization. Available online at www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/en. Accessed 10 May 2017

Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision. 2012: New York Available online at https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/publications/Files/WPP2012_HIGHLIGHTS.pdf. Accessed at 17 June 2016

Kannus P, Parkkari J, Sievänen H, Heinonen A, Vuori I, Järvinen M (1996) Epidemiology of hip fractures. Bone 18(1):S57–S63. https://doi.org/10.1016/8756-3282(95)00381-9

Johnell O, Kanis J (2005) Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 16(2):S3–S7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-004-1702-6

Dhanwal DK, Siwach R, Dixit V, Mithal A, Jameson K, Cooper C (2013) Incidence of hip fracture in Rohtak district. North India Arch Osteoporos 8(1–2):135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-013-0135-2

Clark P, Lavielle P, Franco-Marina F et al (2005) Incidence rates and life-time risk of hip fractures in Mexicans over 50 years of age: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int 12:2025–2203

Hannan MT, Felson DT, Dawson-Hughes B et al (2000) Risk factors for longitudinal bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis study. JBMR 15(4):710–720

Cooper C, Melton LJ 3rd (1992) Epidemiology of osteoporosis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 3(6):224–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/1043-2760(92)90032-V

Sterling RS (2011) Gender and race/ethnicity differences in hip fracture incidence, morbidity, mortality, and function. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469(7):1913–1918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-010-1736-3

William G, Hawkes WG, Wehren L et al (2006) Gender differences in functioning after hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 61(5):495–499

Becker C, Crow S, Toman J, Lipton C, McMahon DJ, Macaulay W, Siris E (2006) Characteristics of elderly patients admitted to an urban tertiary care hospital with osteoporotic fractures: correlations with risk factors, fracture type, gender and ethnicity. Osteoporos Int 17(3):410–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-0001-1

Löfman O, Berglund K, Larsson L, Toss G (2002) Changes in hip fracture epidemiology: redistribution between ages, genders and fracture types. Osteoporos Int 13(1):18–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s198-002-8333-x

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17(12):1726–1733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4

South African History Online. Pass laws in South Africa 1800–1994. (2000) Available online at: www.sahistory.org.za › History of Women's struggle in South Africa. Accessed at 17 June 2016

Peer N, Lombard C, Steyn K, Levitt N (2014) Rising alcohol consumption and a high prevalence of problem drinking in black men and women in Cape Town: the CRIBSA study. J Epidemiol Community Health 68(5):446–452. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-202985

Lau EM, Lee JK, Suriwong P et al (2001) The incidence of hip fractures in four Asian countries: the Asian Osteoporosis Study (AOS). Osteoporos Int 12(3):239–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980170135

Jha RM, Mithai A, Malhotra N, Brown EM (2010) Pilot case-control investigation of risk factors for hip fractures in the urban Indian population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 11:49. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-11-49

Arakaki H, Owan I, Kudoh H, Horizono H, Arakaki K, Ikema Y, Shinjo H, Hayashi K, Kanaya F (2011) Epidemiology of hip fractures in Okinawa, Japan. J Bone Miner Metab 29(3):309–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-010-0218-8

Filip RS, Zagorski J (2005) Osteoporosis risk factors in rural and urban women from the Lublin region of Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med 12(1):21–26

Finsen V, Benum P (1987) Changing incidence of hip fracture in rural and urban areas of central Norway. Clin Orthop Relat Res 218:104–110

Madhok R, Melton LJ, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM, Lewallen DG (1993) Urban vs rural increase in hip fracture incidence: age and sex of 901 cases 1980-89 in Olmsted County, USA. Acta Orthop Scand 64(5):543–548. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453679308993689

Jonsson B, Gardsell P, Johnell O et al (1992) Differences in fracture pattern between an urban and a rural population of comparative population-based study in southern Sweden. Osteoporos Int 2(6):269–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01623181

Chevalley T, Herrmann FR, Delmi M et al (2002) Evaluation of the age-adjusted incidence of hip fractures between urban and rural areas: the difference is not related to the prevalence of institutions for the elderly. Osteoporos Int 13(2):113–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980200002

Brennan SL, Pasco JA, Urquhart DM, Oldenburg B, Hanna FS, Wluka AE (2009) The association between urban or rural locality and hip fracture in community-based adults: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 64(8):656–665. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.085738

Statistics South Africa. General household survey in P0318 General household survey (2014) Pretoria. Available at https://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/526/download/7309. Accessed 19 May 2016

Hough FS, Ascott-Evans BH, Brown SL et al (2010) NOFSA guideline for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis. JEMDSA 15(3):Supple 2

Funding

This study was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Servier® and the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of University of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), and study approval was obtained from the KZN Provincial Department of Health and from all the hospitals involved in the study. The study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines and principles of the International Declaration of Helsinki and South African Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paruk, F., Matthews, G. & Cassim, B. Osteoporotic hip fractures in Black South Africans: a regional study. Arch Osteoporos 12, 107 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-017-0409-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-017-0409-1