Abstract

Associations between loneliness, materialism, and life satisfaction were examined in a sample of 366 Malaysian undergraduate students. Also examined was the mediating role of materialism in the relation between loneliness and life satisfaction, and such a mediational link (i.e., loneliness–materialism–life satisfaction) is expected to be moderated by gender. Loneliness was significantly and positively associated with materialism but negatively associated with life satisfaction. Materialism was significantly and negatively associated with life satisfaction. In addition to these direct associations, materialism emerged as a significant partial mediator in the relation between loneliness and life satisfaction. As predicted, gender moderated the loneliness–materialism–life satisfaction relationship. In particular, materialism significantly mediated such a link for male undergraduate students but not for female undergraduate students. Theoretical and practical implications of the findings for youth wellness are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past few decades, there has been considerable research literature exploring the nature of subjective well-being (SWB). Under the SWB umbrella, life satisfaction has garnered the most research attention. As a cognitive component of SWB, life satisfaction refers to one’s general judgment of life conditions resulting from his or her personal standards (Diener et al. 1985) and is associated with a number of positive outcomes (Buelga et al. 2008; Koskenvuo 2004; Swami et al. 2007; Trzcinski and Holst 2008). The degree to which one’s expectation that he or she can successfully perform behaviors to achieve desired outcomes in real life situations could reflect his or her life satisfaction. To this end, a mismatch between one’s expectations and real life situations could result life dissatisfaction.

The current study aims to address two research gaps by examining the associations between loneliness, materialism, and life satisfaction. First, a large body of research has shown that loneliness and materialism could exert potential influence on life satisfaction (Kau et al. 2000; Swami et al. 2007). However, it is worth mentioning that few studies, if any, have examined the effect of loneliness on life satisfaction taking into account the possible mediating role of materialism. Second, associations between loneliness, materialism, and life satisfaction are not limited with a simple mediation model. It is plausible that such a mediational model could be moderated by gender. In this regard, we will begin by providing a literature review covering the theoretical background of our study.

2 Loneliness, Materialism, and Life Satisfaction

The study of interconnections between loneliness, materialism, and life satisfaction draws upon Adlers’ individual psychology theory (Adler 1959; Ansbacher and Ansbacher 1956), which proposes that social interest, a feeling of relatedness toward others, is useful to against the feeling of inferiority. Adler (1959) also noted that, in the presence of inferiority, people would drive to seek compensation, a self-defense mechanism that hinder one’s to feel weak and frustrated. In his theory, Adler (1959) postulated that men are relatively inherently dominating compared to women (henceforth referred to masculinity protest). In particular, masculinity protest is featured when men are thought to be strong, self-reliant, and in control. In other words, men might develop a stronger goal to become superior; which in turn, they can form and sustain higher levels of self-esteem and self-worth. It is often regarded as a sign of weakness or an admission of failure, if men try to ask for help from others (Adler 1959; Ansbacher and Ansbacher 1956).

Loneliness, a lack of sense and opportunities for social integration and emotional intimacy, has been shown to play a central role in the study of life satisfaction (Perlman 2004; Rook 1984). In this regard, the needs for affiliation and social bonding are associated with one’s well-being. There is evidence to support that loners are at greater risk for low life satisfaction (Ang and Mansor 2012; Buelga et al. 2008; Shahini 2010; Swami et al. 2007). One’s unpleasant feelings toward social network could prompt his or her negative viewpoints pertaining to life satisfaction. Often, loners feel nowhere to disclose their feelings; as a result, they feel empty and unwanted.

There is lack of research that specifically examined the relation between loneliness and materialism. In one study, Kim et al. (2003) reported that loners usually avoid social interaction and are more attracted to conspicuous consumption—a salient compensatory strategy to combat loneliness. Materialism can be affected by the need to fulfill internal emptiness and psychological insecurity among loners (Cryder et al. 2008; Kasser 2002). In pursuit of material objects, loners gain a sense of security or calmness. In support of this premise, Clark et al. (2011) found that people with insecurity were five times more likely to place a monetary value on possessions than those people with interpersonal security.

Materialism is defined as a set of core beliefs (e.g., possession-defined success, acquisition centrality, and acquisition as the pursuit of happiness) that directs one’s behaviors and thoughts about the importance of possessions and is negatively associated with life satisfaction (Christopher et al. 2007; Kasser 2002; Kau et al. 2000; Sirgy 1998; Richins and Dawson 1992; Ryan and Dziurwiec 2000). Although it is universally accepted that material possessions are essential for physiological needs, Kasser’s (2002) notions suggest that one’s material possessions could elicit happiness is often misleading. The pursuit of materialism can be daunting as people are always distracted by temporary pleasure. While materialists are relentlessly searching for more goods, they might gradually develop an unconscious desire for possessions. This could contribute to a negative impact on their life satisfaction (Arndt et al. 2004; Cryder et al. 2008).

2.1 Materialism as a Mediator

Loneliness could act as a precursor to materialism. Such an emotional state could lead the loners to seek for a compensatory strategy (Adler 1959; Baumeister and Leary 1995; Swami et al. 2007). Indeed, one’s attachment to material objects could help he or she to release aversive mood states and to create a stronger sense of self-worth (Cryder et al. 2008; Kasser 2002; Kim et al. 2003; Zhou and Gao 2008). Materialism could project individuals to poor social adjustment, however. It appears that an over-reliance on object-based need fulfillment could result negative cycles or poor well-being (Kau et al. 2000; Ryan and Dziurwiec 2000; Sirgy 1998). Following the logic outlined previously, materialism could be a potential mediator of the relation between loneliness and life satisfaction. This study therefore set out to test the mediating role materialism between loneliness and life satisfaction.

2.2 Gender as a Moderator

Despite the direct link between loneliness and life satisfaction, there is evidence to support that gender could be a moderator in the relation between loneliness and materialism (Kim et al. 2003). Research findings exploring the impact of gender in young people, on loneliness, yields mixed results. In some studies, males reported greater loneliness than females (Ang and Mansor 2012; Shahini 2010). In other studies, similar patterns of findings emerged in both males and females (Archibald et al. 1995). In a recent meta-analysis based on data from 31 studies, Mahon et al. (2006) found that findings from 19 studies showed no significant gender differences on loneliness. However, findings from nine studies reported that boys were significantly lonelier than girls, two studies found girls were significantly lonelier than boys, and one study did not examine gender differences in terms of loneliness. One possible explanation for this inconsistency in Mahon et al’s. (2006) findings is that males are relatively weaker in terms of socialization skills and have smaller social networks compared to females (Borys and Perlman 1985; Knox et al. 2007). Gender stereotype, too, is probably responsible for these inconsistent findings. In Asian countries, independence is highly valued in males (Borys and Perlman 1985). In support of this premise, males tend to hide their loneliness; thus, their emotional disclosure with others is relatively low (Shahini 2010). Additionally, masculine traits such as self-centeredness and assertiveness could reflect men’s inflated egos and aggressive tendencies and are associated with stronger materialistic tendencies (Kamineni 2005; Kasser 2002). For the sake of self-image, compared to females, males tend to demonstrate a stronger interest in material pursuits as a result of high manifestation of loneliness, self-confidence, power, and control (Kasser 2002; Kim et al. 2003; Richins and Dawson 1992). However, if they failed to attain what they want, their life satisfaction could be affected (Kau et al. 2000). Taken together, we expected that gender may play a moderational role in the loneliness–materialism–life satisfaction relationship.

3 Method

3.1 Participants

A sample of 366 undergraduate students (182 males, 184 females) from one public university in Malaysia participated in this study. Participants’ age ranged from 19 to 24 years old, with a mean age of 21.40 (SD = 1.51). As far as ethnicity is concerned, 89.6 % of the participants were Malay, 7.5 % were Chinese, 2.4 % were Indian, and 0.5 % endorsed others (ethnic group not listed). In terms of cross-cultural variability, Malaysia is traditionally regarded as a collectivistic society—members tend to highly value family needs, sense of belonging, and achievement of goals (Triandis 2001). However, as a result of modernization processes, the cross-cultural variability has been shifted to an individualistic society with respect to the way of defining a good life (i.e., consumption is good and by this, you will be happier). This is consistent with Burroughs and Rindfleisch’s (2002) notions that consumption is a culturally accepted means of seeking life successfulness and happiness. A common misperception is that one’s personal wealth possessions could provide an indication of happiness (Richins 2004). Like Western societies, there is a growing preoccupation with possessions among youths in Malaysia (Dolliver 2007). Taken together, it is plausible that attempts to reduce loneliness in Malaysian youths could be driven by material pursuits.

3.2 Procedure

Prior to data collection, approval for data collection was sought from the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Malaysia. Participation was voluntary and participants were informed that they could refuse participation at any time, without penalty. After informed consent had been sought, we then gave participants a questionnaire packet and asked them to complete and return it after 30 min. All questionnaires were administered in English.

3.3 Measures

Participants completed a questionnaire packet comprising the University California Loneliness Scale (Version 3; Russell 1996), the Material Values Scales (Richins 2004), and Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985).

3.3.1 University California Loneliness Scale (UCLA Version 3)

The 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3; Russell 1996) measures participants’ subjective judgment on interpersonal relationships. Participants responded to each item on a 4-point Likert ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). A composite score was computed by summing 11 positive and 9 negative items (scores were reversed for negative items beforehand). Higher scores indicate greater loneliness.

3.3.2 Material Values Scale (MVS)

The 15-item MVS (Richins 2004) assesses participants’ inclination toward three materialistic orientations, including acquired happiness, acquired centrality, and success. Participants responded to each item on a 5-point Likert ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). For the purposes of the study, only the total score was used. A total score was computed by summing 9 positive items and 6 negative items (scores were reversed for negative items beforehand). A higher score indicates greater endorsement of materialism beliefs.

3.3.3 Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

The 5-item SWLS (Diener et al. 1985) measures participants’ cognitive judgment on life quality in general. Participants responded to each item on a 7-point Likert ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction with life.

3.4 Data Analytic Plan

In the present study, analysis of moment structures (AMOS version 18) with maximum likelihood estimation was used. An examination of psychometric properties of study variables was completed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Multiple fit indexes were used to evaluate the adequacy of the models: Goodness Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness Fit Index (AGFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Cut off values of .90 and .08, respectively, for GFI, AGFI, CFI, and NFI and RMSEA indicate acceptable model fit (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Using Baron and Kenny’s (1986) recommendations, the role of materialism as a mediator in the relation between loneliness and life satisfaction was examined (for a full review, see Baron and Kenny 1986). To increase robustness, bootstrapping was used to test if the mediated effect detected was statistically significant (Preacher and Hayes 2008). To generate confidence limits for mediated effects, significance tests based on bias-corrections of 95 % were obtained (MacKinnon et al. 2004). Finally, a multigroup analysis was performed to evaluate whether structural paths were found to differ by gender at p < .05, taking into account the mediating role of materialism in the relation between loneliness and life satisfaction.

4 Results

4.1 Confirmatory Factor Analyses

A series of CFAs were performed to examine the psychometric properties of UCLA, MVS, and SWLS (see Table 1). In the case of UCLA, the single factor measurement model did not provide a good fit to the data. χ2 (170, N = 366) = 996.39, p = .00; GFI = .70; AGFI = .63; CFI = .70; NFI = .67; RMSEA = .12. In this regard, a two-factor model was tested next. We collapsed positive and negative items into two separate factors. When this was done, the final model fit the data better, χ2 (165, N = 366) = 374.62, p = .00; GFI = .90; AGFI = .88; CFI = .93; NFI = .88; RMSEA = .06. The reliability of the scale in the present study was good (α = .89).

For MVS, a second-order CFA model with three underlying factors (i.e., centrality, success, and happiness) was tested. The initial model did not provide a good fit to the data, χ2 (83, N = 366) = 300.29, p = .00; GFI = .90; AGFI = .85; CFI = .81; NFI = .75; RMSEA = .08. Wong et al. (2003) argued that mixed worded items did not work reasonably well among Asian populations, such as Singaporeans, Koreans, Thai, and Japanese. The authors posited that mixed worded items may impose a threat to measurement equivalence and construct validity. As a result, we removed all six reversed items. The final model was presented by nine observed indicators. When this was done, the final model fit the model better, χ2 (20, N = 366) = 61.56, p = .00; GFI = .97; AGFI = .92; CFI = .95; NFI = .93; RMSEA = .08. The reliability of the scale in the study was adequate (α = .74).

With respect to SWLS, the single-factor measurement model provided a good fit to the data, χ2 (4, N = 366) = 8.59, p = .00; GFI = .99; AGFI = .96; CFI = .99; NFI = .99; RMSEA = .06. The reliability of the scale was good (α = .88).

Finally, a measurement model consisted of constructs of interest was conducted. The model provided a good fit to the data, χ2 (508, N = 366) = 1,008.89, p = .00; GFI = .91; AGFI = .90; CFI = .95; NFI = .90; RMSEA = .05. All items had moderate to high factor loadings ranging between .60 and .81, ps < .05.

4.2 Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 summarizes the means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis of study variables. Skewness and kurtosis indexes were within acceptable limits for the present sample (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). In addition, assumptions of multicollinearity (i.e., variance inflation factors) and multivariate normality (i.e., Mardia’s coefficient) were satisfied (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001).

Female undergraduates reported a higher level of life satisfaction (M = 23.36, SD = 5.71) and lower levels of materialism (M = 29.18, SD = 4.58) and loneliness (M = 46.30, SD = 9.13) as compared to male undergraduates (for life satisfaction, M = 20.74, SD = 6.49, t(364) = −4.10, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .43; for materialism, M = 31.12, SD = 5.08, t(364) = 3.83, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .40; for loneliness, M = 49.24, SD = 8.63, t(364) = 3.16, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .33). Cohen’s d ranged from .33 to .43, suggesting that the effects are approximately small to medium (Cohen 1988).

4.3 Intercorrelations Among Variables

Table 3 presents the correlational relations among study variables. Loneliness was significantly and positively correlated with materialism (r = .36, Cohen’s d = .77, p < .001) but negatively with life satisfaction (r = −.48, Cohen’s d = 1.09, p < .001). Materialism was significantly and negatively correlated to life satisfaction (r = −.33, Cohen’s d = .70, p < .001). Cohen’s d ranged from .70 to 1.09, suggesting that these effects are approximately medium to large (Cohen 1988).

4.4 Materialism as a Mediator

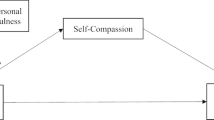

Table 4 and Fig. 1 present the results for testing the meditational hypotheses for the present sample. Our mediational model includes loneliness as an exogenous variable, materialism as a mediator, and life satisfaction as an endogenous variable. In Step 1, we tested the direct effect of loneliness on life satisfaction. This requirement was satisfied: The direct effect of loneliness on life satisfaction was statistically significant (β = −.48, p < .01). In Step 2, we tested the mediating role of materialism on the relation between loneliness and life satisfaction. Materialism was found to be predicted by loneliness (β = .36, p < .01) and was itself a predictor of life satisfaction (β = −.18, p < .01). Likewise, this requirement was satisfied. The path coefficient for the direct effect of loneliness on life satisfaction was significant, but its magnitude decreased when materialism being controlled for (β = −.41, p < .01).

In the present study, the meditational analysis was further enhanced by the use of bootstrapping technique (Preacher and Hayes 2008). Our findings yielded a significant mediated effect of materialism on the relation between loneliness and life satisfaction (β = −.06, p < .01) with a 95 % CI [−.11, −.03]. The direct effect of loneliness on life satisfaction was remained statistically significant, suggesting that materialism only partially mediated the loneliness–life satisfaction relation. As expected, materialism significantly mediated the relation between loneliness and life satisfaction.

4.5 Gender as a Moderator

Table 5 and Fig. 2 present the results for testing the moderated mediation hypotheses in the present study. We performed a multi-group analysis to examine whether loneliness–materialism–life satisfaction relation was moderated by gender. SEM results yielded statistically significant path coefficients from loneliness to materialism and life satisfaction for males (for materialism, β = .29; for life satisfaction, β = −.43, ps < .001) and females (for materialism, β = .40; for life satisfaction, β = −.39; ps < .001). The negative association between materialism and life satisfaction was remained statistically significant for male undergraduate students (β = −.19, p < .01); however, the direct effect of materialism on life satisfaction for female undergraduate students did not reach significance (β = −.12, p > .05).

The bootstrapping analyses further revealed that indirect effect of loneliness on life satisfaction via materialism for males reached significance, β = −.05, SE = .03, p < .01 with a 95 % CI [−.12, −.02]. On the other hand, the indirect effect of loneliness on life satisfaction via materialism for female undergraduate students did not reach significance, β = −.05, SE = .03, p > .05 with a 95 % CI [−.11, .01]. As expected, materialism significantly mediated the effect of loneliness on life satisfaction for male undergraduate students but not for female undergraduate students.

5 Discussion

The primary goal of the study was to investigate the relations between loneliness, materialism, and life satisfaction in a sample of Malaysian undergraduate students. Our findings suggest that loneliness and materialism were negatively associated with life satisfaction. These findings are in line with previous research (Buelga et al. 2008; Christopher et al. 2007; Mahon et al. 2006; Richins and Dawson 1992; Ryan and Dziurwiec 2000; Shahini 2010). There is limited research on this topic area using Asian samples (Kim et al. 2003; Swami et al. 2007). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine this pattern of relationship using an undergraduate sample from Malaysia. The findings also add to a growing body of literature on materialism. The results of this study indicate that higher levels of loneliness were associated with higher levels of materialism. In other words, loners feel a greater need for material pursuits. The results of this research support the premise that one’s social need, in part, can shape his or her view of material pursuits (Clark et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2003; Zhou and Gao 2008). Apparently, one’s deep bond and strong emotional attachment with others is a protective factor to against materialism. In this regard, intervention efforts could target on youth psycho-educational training. This can help youths to improve their interpersonal relationships and to help them to feel valued, connected, and secure (Rook 1984).

Less research attention was given to the underlying mechanism between loneliness and life satisfaction. Our study provides evidence that materialism could play a mediating role in the relation of loneliness to life satisfaction. A theoretical implication of this finding is the possibility that young adolescents with high levels of loneliness to have higher materialism, which in turn, are associated with lower levels of life satisfaction. With the application of Adler’s individual psychology theory, the current findings add substantially to our understanding of one’s need for social contact and connection in predicting life satisfaction. As previously mentioned, individuals’ social interest could affect them to seek for compensatory superiority strivings (Adler 1959; Ansbacher and Ansbacher 1956). Pecuniary reward, as posited by Clark et al. (2011), is one of the most appealing compensatory strategies for psychological insecurity. It appears that individuals tend to draw positive inferences vis-à-vis life happiness if they possessed more extrinsic materials (Kasser 2002). This could contribute to an overriding tendency to establish a permanent parasitic relationship with material possessions (Christopher et al. 2006; Sirgy 1998). This notion is consistent with need to belong and self-determination theory (for a full review, see Baumeister and Leary 1995; Ryan and Deci 2000). Loners tend to develop a lower level of social interest as compared to their non-lonely counterparts. These authors also suggested that being a loner is associated with higher levels of shyness, inferiority, and insecurity. As evident in Kasser’s (2002) study, loners endorsed higher levels of extrinsic goals (e.g., financial success, image, and popularity) and lower levels of intrinsic goals (e.g., personal growth, affiliation, and community involvement) compared to their non-lonely counterparts. It is fairly accepted that one’s pursuit of extrinsic goals could lead to excessive interpersonal comparisons and low life satisfaction (Brown et al. 2008).

Our findings also shed light that the indirect effect of loneliness on life satisfaction (through materialism) was moderated by gender. In particular, materialism emerged as a significant mediator in the relation between loneliness and life satisfaction for male undergraduate students, but not for female undergraduate students. According to Alder’s individual psychology theory (Ansbacher and Ansbacher 1956), men are generally viewed as independent, strong, and competitive. In view of socio-cultural context in Malaysia, male supremacy is even more firmly ingrained than those in many other Western countries (Gibbons et al. 1991). In such a patriarchal society, descriptions such as superiority and competitiveness are associated with men (Best and Williams 1994). It is not socially appropriate for men to admit their weakness (Ang and Mansor 2012; Barrett and Bliss-Moreau 2009). To this end, men do place much emphasize on material pursuit as a sign of life successfulness and happiness (Kamineni 2005). There is considerable debate among psychologists as to whether or not material possessions could buy happiness. For instance, Arndt et al. (2004) argued that material accumulation could elicit a greater sense of personal significance and successfulness. However, Ryan and Dziurwiec (2000) posited that there will be endless point in one’s pursuit of successfulness and material possessions. A considerable amount of consumer research has found that one’s high preoccupation with possession and material strivings could result in his or her high responsiveness towards externals (e.g., trendy possessions, prestige, and fame; Kasser 2002; Kau et al. 2000; Kim et al. 2003; Richins and Dawson 1992). Materialist could suffer from a chronic lack of “stuff”, if they cannot afford to buy everything they really want and their life satisfaction could be affected in the long run.

Like any research, some limitations of this study should be addressed. First, the present study was limited in terms of sampling. Although its size was adequate for statistical analyses, it was extremely homogenous both geographically and racially. All participated students were from only one university and almost all were Malay. Thus, the findings’ generalizability should be interpreted with caution. Future studies should to consider collecting data from a large, heterogeneous sample. The second limitation concerns in the form of causality related to the loneliness–materialism–life satisfaction relationship. This issue cannot be completely ruled out in view of cross-sectional nature of the present sample. Longitudinal research would be beneficial to establish the causality between constructs. Third, all the collected data came in the single form of self-report measures; thus, the problems of common method bias are potentially raised. To increase validity and predictivity of study variables, objective scores pertaining to students’ psychosocial and subjective functioning could be considered in future studies. Lastly, despite the need for the identification of materialism as a mediator and gender as a moderator, respectively, in the relation between loneliness and life satisfaction and in the relation between loneliness–materialism–life satisfaction, there could be other potential mediators (e.g., social support; Kapıkıran 2013) and moderators (e.g., personality traits; Howell et al. 2012) which were not included in the present study.

6 Summary

The present study examined two models: materialism as a mediator in loneliness and life satisfaction relationship and gender as a moderator in loneliness–materialism–life satisfaction relationship. In particular, the findings indicate that undergraduate students with high levels of loneliness to have higher materialism, which in turn, are associated with life dissatisfaction. Gender significantly moderated the indirect effect of loneliness on life satisfaction through materialism for male undergraduate students but not for female undergraduate students. Prevention and intervention programs may emphasize the importance of social interactions and emotional attachment with others. Such programs can help to alert one’s unconscious desire for material possessions.

References

Adler, A. (1959). Understanding human nature. New York: Premier Books.

Ang, C. S., & Mansor, A. T. (2012). An empirical study of selected demographic variables on loneliness among youths in Malaysian university. Asia Life Sciences, 21, 107–121.

Ansbacher, H. L., & Ansbacher, R. R. (1956). The individual psychological of Alfred Adler. New York: Basic Books.

Archibald, F. S., Bartholomew, K., & Marx, R. (1995). Loneliness in early adolescence: A test of the cognitive discrepancy model of loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 296–301.

Arndt, J., Solomon, S., Kasser, T., & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). The urge to splurge: A terror management account of materialism and consumer behavior. Journal Consumer Psychology, 14, 198–212.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Barrett, L., & Bliss-Moreau, E. (2009). She’s emotional. He’s having a bad day: Attributional explanations for emotion stereotypes. Emotion, 9, 648–658.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachment as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Best, D. L., & Williams, J. E. (1994). Masculinity/femininity in the self and ideal self descriptions of university students in fourteen countries. In A. M. Bouvy, F. van de Vijver, P. Boski, & P. Schmitz (Eds.), Journeys into cross cultural psychology: Selected papers from the Eleventh international conference of the international association for cross cultural psychology. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Borys, S., & Perlman, D. (1985). Gender differences in loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 11, 63–74.

Brown, G. D. A., Gardner, J., Oswald, A. J., & Qian, J. (2008). Does wage rank affect employees’ well-being? Industrial Relations, 47(3), 355–389.

Buelga, S., Musitu, G., Murgui, S., & Pons, J. (2008). Reputation, loneliness, satisfaction with life and aggressive behavior in adolescence. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 11, 192–200.

Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2002). Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(348), 370.

Christopher, A. N., Drummond, K., Jones, J. R., Marek, P., & Therriault, K. M. (2006). Beliefs about one’s own death, personal insecurity, and materialism. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 441–451.

Christopher, A. N., Lasane, T. P., Troisi, J. D., & Park, L. E. (2007). Materialism, defensive and assertive self-presentational styles, and life satisfaction. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 1146–1163.

Clark, M. S., Greenberg, A., Hill, E., Lemay, E. P., Clark-Polner, E., & Roosth, D. (2011). Heightened interpersonal security diminishes the monetary value of possessions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 359–3654.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Cryder, C. E., Lerner, J. S., Gross, J. L., & Dahl, R. E. (2008). Misery is not miserly: Sad and self-focused individuals spend more. Psychological Science, 19, 525–530.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Dolliver, M. (2007). At least you can’t accuse the kids of wallowing in bogus selflessness. Adweek, 48(4), 26.

Gibbons, J., Stiles, D. A., & Shkodriani, G. M. (1991). Adolescents’ attitudes toward family and gender roles: An international comparison. Sex Roles, 25(11–12), 625–643.

Howell, R. T., Pchelin, P., & lyer, R. (2012). The preference for experiences over possessions: Measurement and construct validation of the experiential buying tendency scale. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(1), 57–71.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Kamineni, R. (2005). Influence of materialism, gender and nationality on consumer brand perceptions. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 14, 25–32.

Kapıkıran, Ş. (2013). Loneliness and life satisfaction in Turkish early adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem and social support. Social Indicators Research, 111, 617–632.

Kasser, T. (2002). The high price of materialism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kau, A. K., Kwon, J., Jiuan, T. S., & Wirtz, J. (2000). The influence of materialistic inclination on values, life satisfaction and aspirations: An empirical analysis. Social Indicators Research, 49, 317–333.

Kim, Y., Kim, E. Y., & Kang, J. (2003). Teens’ mall shopping motivations: Functions of loneliness and media usage. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 32, 140–167.

Knox, D., Vail-Smith, K., & Zusman, M. (2007). The lonely college male. International Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 273–279.

Koskenvuo, M. (2004). Life satisfaction and depression in a 15-year follow-up of health adults. Social Psychiatric Epidemic, 39, 994–999.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128.

Mahon, N. E., Yarcheski, A., Yarcheski, T. J., Cannella, B. L., & Hanks, M. M. (2006). A meta-analytic study of predictors for loneliness during adolescence. Nursing Research, 55, 308–315.

Perlman, D. (2004). European and Canadian studies of loneliness among seniors. Canadian Journal on Aging, 23, 181–188.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Richins, M. L. (2004). The material values scale: Measurement properties and development of a short form. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 209–219.

Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 303–316.

Rook, K. S. (1984). Promoting social bonding: Strategies for helping the lonely and socially isolated. American Psychologist, 39, 1389–1407.

Russell, D. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 10–40.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Ryan, L., & Dziurwiec, S. (2000). Materialism and its relationship to life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 55, 185–197.

Shahini, N. (2010). A study gauging perceived social support and loneliness with life satisfaction among students of Golestan University of Medical Sciences. European Psychiatry, 25, 842.

Sirgy, M. J. (1998). Materialism and quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 43, 227–260.

Swami, V., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Sinniah, D., Maniam, T., Kannan, K., Stanistreet, D., et al. (2007). General health mediates the relationship between loneliness, life satisfaction and depression: A study with Malaysian medical students. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42, 161–166.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924.

Trzcinski, E., & Holst, E. (2008). Subjective well-being among young people in transition to adulthood. Social Indicator Research, 87, 83–109.

Wong, N. Y., Rindfleisch, A., & Burroughs, J. E. (2003). Do reverse-worded items confound measures in cross-cultural consumer research? The case of the material values scale. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 72–91.

Zhou, X., & Gao, D.-G. (2008). Social support and money as pain management mechanisms. Psychological Inquiry, 19, 127–144.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the study participants for their cooperation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ang, CS., Mansor, A.T. & Tan, KA. Pangs of Loneliness Breed Material Lifestyle but Don’t Power Up Life Satisfaction of Young People: The Moderating Effect of Gender. Soc Indic Res 117, 353–365 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0349-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0349-0