Abstract

Previous studies have shown a negative relationship between loneliness and one’s subjective well-being. However, it has not been fully examined within the Chinese context which highlights the importance of social relationship and interpersonal harmony for one’s life, and the mechanism between them has not been thoroughly explored. Based on social cognitive theory, this study examined the main effects of loneliness on individuals’ stress, depression, and life satisfaction, as well as the mediating effect of self-efficacy between them. Survey data were obtained from 444 Chinese undergraduates. The results of multiple regressions revealed that loneliness was negatively correlated with life satisfaction and positively correlated with stress and depression. Moreover, self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between loneliness and stress, as well as depression, and fully mediated the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Loneliness is one of the most pervasive human experiences for people from all walks of life (Ilhan 2012; Tharayil 2012; Weiss 1973). It was defined as “the unpleasant experience that occurs when a person’s network of social relationships is significantly deficient in either quality or quantity” (Perlman and Peplau 1984, p. 15). Different from objective social isolation, loneliness is subjective in that one may live a relatively solitary life but not feel lonely, but one may feel lonely even amongst a crowd of people (Hawkley and Cacioppo 2010). Previous studies have demonstrated that loneliness is related to one’s well-being, such as poor life satisfaction (e.g., Salimi 2011), depression (e.g., Alpass and Neville 2003), substance abuse (e.g., Rokach 2005a), and poor health (e.g., Hawkley et al. 2006). However, how loneliness influences individual subjective well-being (SWB) is still understudied and there are two theoretical gaps in the existing research.

First, the relationship between loneliness and one’s SWB has not been fully examined within the Chinese context. Previous research has mostly focused on the impact of Chinese people’s personalities such as core self-evaluations (Cai et al. 2009; He et al. 2013), self-concordance (Sheldon et al. 2004), self-concept (Cheng et al. 2011), self-perception (Lischetzke et al. 2012), and cross-cultural personality (Chen et al. 2006) on their SWB, whereas only a handful of studies have probed into the influence of social interaction such as social support (Kong and You 2013; Kong et al. 2013) and interpersonal harmony (Hsiao et al. 2006) on one’s SWB. Given that China has been identified as a typical collectivistic (Triandis 2001) and guanxi-orientated (Mao et al. 2012) country, which indicates that the Chinese emphasize the importance of social relations in their self-concept and meaningfulness of life, they are thus more motivated by social relations compared with people in an individualistic culture (Markus and Kitayama 1991). It is therefore imperative to pay more attention to the effect of deficiencies in social interaction like loneliness on Chinese people’s SWB.

As loneliness is perceived as social isolation which implies social rejection, it may be more context-sensitive in the Chinese context for the following reasons: First, interpersonal dynamics are central to the Chinese self-concept (Hsiao et al. 2006). Compared with people in an individualistic culture who are more self-centered and independent, the Chinese tend to construct their sense of self as interdependent and derive their sense of safety, identity, and self-worth from the group they belong to (Lim and Chang 2009). Accordingly, the Chinese people’s personal identity may be threatened by the deficit in their social relationships. Second, the cultural norm of Confucianism requires that individuals should assume responsibilities and obligations towards the group and others. Under such standards for interpersonal relationships, an individual is supposed to fulfill his/her duty and expected roles in the social hierarchy (Bedford and Hwang 2003). However, as lonely people usually lack adequate social interaction with others, it is unlikely for them to meet such cultural expectations, which may result in their mental maladjustment. Third, interpersonal harmony has long been emphasized in traditional Confucian ideology (Cheung et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2014). It refers to the balance achieved within an individual’s various relationships. As deeply influenced by the cultural values, interpersonal stimuli is perceived by Chinese people as the salient source of stress (Lun and Bond 2006). For lonely people who have poor social skills, they are confronted with more relationship disharmony that may afflict them in everyday life.

Second, the mechanism between loneliness and one’s SWB has not been thoroughly examined. Existing studies have argued that physical conditions (e.g., general health; Swami et al. 2007) and psychological needs (e.g., social support; Azam et al. 2013) mediated the relationship between loneliness and one’s SWB. Nevertheless, as Perlman and Peplau (1984) suggested, more attention should be paid to the cognitive mechanism between loneliness and its negative outcomes. Based on social cognitive theory, the present study attempts to examine the mediating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between loneliness and one’s SWB.

In conclusion, we aimed to provide empirical evidence of the relationship between loneliness and one’s SWB in the Chinese context and to explore the mediating role of self-efficacy between them, which will enrich the research concerning Chinese people’s SWB and open the black box between loneliness and individual SWB.

2 Theories and Hypotheses

Subjective well-being refers to people’s cognitive and affective evaluations of their life (Busseri and Sadava 2011; Eid and Larsen 2008). It consists of three major components: the frequency of positive and negative affect, as well as the cognitive evaluation of global life satisfaction (Diener et al. 1999). In this study, we focused on its negative affect (i.e., stress and depression) and cognitive component (i.e., life satisfaction) for the following reasons. First, numerous studies confirmed that stress and depression had adverse effect on one’s quality of life (e.g., Abbey and Andrews 1985; Caron 2012; Lever et al. 2005; Magee and St-Arnaud 2012; Ostir et al. 2007). Second, overall life satisfaction is the most significant indicator of individuals’ SWB (Diener 2009). Third, SWB has been conceptualized as life satisfaction, stress, and depression in previous research (e.g., Diener et al. 1999, 2009; Magee and St-Arnaud 2012). Thus, we conceptualized a person’s SWB as stress, depression, and life satisfaction and examined how loneliness influences them.

2.1 Loneliness and Stress

Stress is the situation in which the environmental demands are perceived to exceed the coping resources (Cohen et al. 1983; Monat and Lazarus 1991). Ursin and Eriksen (2004) indicated that there are four aspects of stress: Stress stimuli, stress experience, stress response, and feedback from the stress response. They suggested that stress disorder is related to uncontrollable and unpredictable negative events in a person’s life. Previous studies have shown that self-conceptions (Thoits 2013), social capital (Chen et al. 2014), and social networks (Gerich 2013) are conceivable antecedents of stress. Stress is generally regarded as debilitating, and prolonged stress may lead to adverse psychological and physical effects such as cognitive impairment (Schwabe et al. 2010), aggression (Bodenmann et al. 2010), and increased risk of premature mortality (Braveman et al. 2011).

We argue that loneliness is positively related to one’s stress. First, as lonely people lack satisfying social relationships, they have little of the necessary social support to cope with various stressors in life (Gerich 2013) and are prone to suffer more stress. Second, as lonely people are often in a gloomy mood or have other declining bodily health symptoms like anorexia or insomnia, they are more likely to have worsened ability to deal with high demanding tasks (Rokach 2005b) and have high stress in the everyday life. Thus we propose:

Hypothesis 1

Loneliness is positively associated with stress.

2.2 Loneliness and Depression

Depression refers to a mood of pronounced hopelessness and overwhelming feeling of inadequacy or unworthiness (Weeks et al. 1980) seen as emotional impairment stemming from environmental or hormonal disorders (Sullivan et al. 2000). Current studies have found that certain personality patterns (e.g., low self-esteem, introversion) are more vulnerable to depression (Chioqueta and Stiles 2005) and that depressive symptoms can be exacerbated by continuous emotional abuse or deteriorating coping capacity (Ng and Hurry 2011). Along with depression, people may face physical, biological, psychological, and social dysfunction (Hallion and Ruscio 2011).

We assume that loneliness is positively related to depression. First, people in a collectivistic culture obtain their self-identity and self-worth from the group they belong to and enhance their self-esteem through group membership; thus people with more social interaction with others will experience less depression (Bartolini et al. 2013; Uusitalo-Malmivaara and Lehto 2013). Second, lonely people who have been rejected from the community they value and treasure may experience low self-esteem (Kapıkıran 2013) and lack of emotional stability (Cacioppo et al. 2006). Along with those negative self-perceptions, lonely people may be more susceptible to feelings of unworthiness or hopelessness, and finally more vulnerable to depression (Tharayil 2012). Thus we propose:

Hypothesis 2

Loneliness is positively associated with depression.

2.3 Loneliness and Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction represents a global cognitive evaluation of a person’s satisfaction with his or her life (Diener et al. 1985). Both situational and personality factors can influence people’s appraisement of their liking or disliking of their life (Heller et al. 2004). Heller et al. (2004) meta-analysis indicates that satisfaction with major life domains such as health, finances, job, and interpersonal relationships are strongly linked to general life satisfaction and people’s perceptions of domain satisfaction are substantially associated with both objective and subjective or dispositional factors (Brief et al. 1993).

We propose that loneliness negatively influences life satisfaction. First, people in a collectivistic culture attach such great importance to maintaining interpersonal relationship harmony (Huo and Kong 2013; Li et al. 2014; Shu and Zhu 2009) that they may negatively appraise their quality of life when faced with such deficits in social relationships as loneliness (Ang et al. 2013). Second, accompanied by loneliness are feelings of hostility, pessimism, anxiety, and low self-esteem (Cacioppo et al. 2006) activating negative experiences in lonely people’s daily lives and contributing to their decreased life satisfaction as a whole. Thus we propose:

Hypothesis 3

Loneliness is negatively associated with life satisfaction.

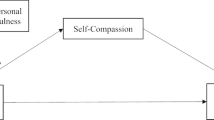

2.4 The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is defined as “the conviction that one can successfully execute the behavior required to produce the outcomes” (Bandura 1977, p. 193). It can be understood as individuals’ general sense of personal competence across various stressful situations (i.e., general self-efficacy, GSE; Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995), or be either task or domain specific (Luszczynska et al. 2005). General self-efficacy emphasizes a person’s general competence to do tasks across situations, but the task self-efficacy emphasizes a person’s capabilities to complete a task in a work setting (Spreitzer 1995). As the participants of this study were undergraduates in a business school who lack work experience and socialization, we conceptualized self-efficacy as general self-efficacy and explored the mediating role of general self-efficacy underlying the association between loneliness and stress, depression, and life satisfaction.

Bandura (1977) proposed that self-efficacy is the consequence of four sources of information: past experience, modeling, social persuasion, and physiological or psychological states. Past experience of failure or success is the most important factor in determining self-efficacy. Modeling refers to the observational experiences provided by a role model. Social persuasion is the encouragement or doubts communicated by significant others. The physiological and psychological states refer to individuals’ positive or negative mood or body symptoms in response to a certain situation. Numerous subsequent empirical studies have also linked personality traits (e.g., Strobel et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2013) and experience (e.g., Shea and Howell 2000) to self-efficacy. According to social cognitive theory, perceived self-efficacy, as the cognitive determinant of behavior, affects individuals’ selection of coping strategies under challenging demands (Bandura 2001), achievement strivings (Luszczynska et al. 2005), level of physiological depression reactions (Hermann and Betz 2006), and emotional states (Cramm et al. 2013).

In light of the four sources proposed by Bandura, we suggest that loneliness can attenuate one’s self-efficacy for the following reasons: First, lonely people lack satisfactory social relationships and the necessary social support, leading to their low ability to attain goals, and thus more experience of failure (Alkire 2005; Beehr et al. 2000). Second, Hawkley and Cacioppo (2010) posit that lonely people tend to be more vigilant to social threats in the environment, which produces cognitive biases and makes them remember more negative social information. Thus, we suppose that lonely people are less active in searching for their role models and may neglect the positive modeling effects others set for them as well. Third, lonely people have few intimate friends or other forms of partners, which results in their rarely receiving encouragement from significant others (Heinrich and Gullone 2006). Fourth, lonely people usually have negative physiological and psychological states such as anxiety (Rokach 2005a), sadness (Tharayil 2012), and poor health (Hawkley et al. 2006), which may attenuate their somatic and emotional arousal level and thus generate low self-efficacy. On the basis of the four aspects argued above, we speculate that lonely people will have lower self-efficacy.

We assume that the associations between loneliness and stress, depression, and life satisfaction are mediated by self-efficacy for the following reasons: First, lonely people who have low self-efficacy are apt to regard the tasks as more difficult than they actually are (Bandura 1993; Schunk 1989). The thought then reduces the efforts they will spend on the task and the time they persist, resulting in frustrating outcomes in turn (Coutinho 2008; Luszczynska et al. 2005). The unwanted facts thus lead to feelings of tension and stress, failure, and depression (Caprara and Steca 2005). Second, lonely people with low self-efficacy are more prone to blame themselves for their social problems and attribute their loneliness to unchangeable factors (Newall et al. 2009; Perlman and Peplau 1984), which may affect the cognitive process of appraisal that is central in determining a person’s overall life satisfaction, thus contributing to a more negative evaluation (Hawkley and Cacioppo 2010). Third, other studies have also indicated that the connection between loneliness and SWB is not straightforward, but mediated by cognitive mechanisms (Cacioppo and Hawkley 2009; Hawkley and Cacioppo 2010; Peplau et al. 1979). Thus we propose:

Hypothesis 4

Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between loneliness and stress (H4a), depression (H4b), and life satisfaction (H4c).

3 Method

3.1 Procedure and Sample

The survey was conducted in a business school at a high-prestige university in central China. We distributed our questionnaires to all the sophomores in this business school with the help of several research assistants. Each participant was told that the investigation was conducted on the nature of voluntary to reduce their concerns and received a small unsealed envelope in which there was a questionnaire as well as a cover letter to illustrate the purpose and the anonymity of the survey. The participants were asked to evaluate their loneliness, self-efficacy, depression, stress, and life satisfaction. When the questionnaires were completed, students were required to place them into the envelopes to submit to the research assistants.

Initially, we distributed 600 student questionnaires. After the distribution-return process, 486 questionnaires were returned at a rate of 81 %. Among the returned questionnaires, 444 of them were valid at a rate of 91.36 %. Of the student sample, 38.4 % were male, and the average age of respondents was 19.02 years (SD = 1.26).

3.2 Measures

With the original version of the measure in English, we adopted the procedure of a double blinded translation suggested by Brislin (1980) to assure the validity and accuracy of the Chinese version. That is, one professional researcher translated the original English version of the scales into Chinese, and the Chinese version was back-translated by two other professional researchers. All of the measure items were rated from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree” and were listed in the appendix.

3.2.1 Loneliness

Loneliness was assessed using the 20-item revised version of the UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Loneliness Scale (R-UCLA) developed by Russell (1996). A sample item was “I lack companionship.” The reliability for the scale was .884.

3.2.2 Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was measured with the ten-item General Self-Efficacy Scale developed by Schwarzer and Jerusalem (1995). A sample item was “I can usually handle whatever comes my way.” The reliability for the scale was .946.

3.2.3 Stress

Stress was evaluated by the 14-item Perceived Stress Scale developed by Cohen et al. (1983) which measures the degree to which situations in a person’s life are appraised as uncontrollable and overloaded. One sample item was “Recently I felt upset because of something that happened unexpectedly.” The reliability for the scale was .711.

3.2.4 Depression

Depression was assessed with the seven-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-Dm) used by Mirowsky and Ross (1992), which measures the frequency of unpleasant symptoms of depressed mood and physiological malaise (Mirowsky and Ross 1986). CES-Dm was correlated with the full CES-D with a coefficient of .92 (Mirowsky and Ross 2001). One sample item was “Recently I felt I just couldn’t get going.” The reliability for the scale was .953.

3.2.5 Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction was assessed by using the five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale, developed by Diener et al. (1985), which refers to the cognitive-judgmental aspects of general life satisfaction. One sample item was “I am satisfied with my life.” The reliability for the scale was .857.

3.2.6 Control Variables

Previous studies have shown that gender and age are associated with SWB (e.g., Huo and Kong 2013; Lent 2004). We thus controlled for these two variables. Gender was coded with 1 representing males and 2 females. Age was recorded as the Arabic numbers.

4 Results

4.1 Common Method Bias Caution

As our data were collected from the same source, concerns regarding common method bias (CMB) may be raised (Malhotra et al. 2006; Podsakoff et al. 2003). We thus conducted Harman’s single-factor test which was a widely used technology in the existing studies to examine the potential CMB between variables, and the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied for Harman’s single-factor test because some evidence showed that it was more sophisticated than the exploratory factor analysis approach. According to Mathiu and Farr’s (1991) recommendation, we parceled the items of every theoretical variable into two factors as two indicators in the structural equation modeling, respectively. We first examined a five-factor model in which we included all five theoretical constructs, then we combined the theoretical constructs step by step, and the fitness indexes of model a to model d were compared to assess the goodness of fit with the different factor structures. Results in Table 1 show that one-factor model provided a worst fit (χ 2 = 2,221, df = 35, CFI = .390, GFI = .546, IFI = .392, RMR = .267, RMSEA = .375), and all the other alternative models yielded poorer fit to the data and fit significantly worse than that of the five-factor model (χ 2 = 109, df = 25, CFI = .976, GFI = .954, IFI = .977, RMR = .037, RMSEA = .087). Thus we concluded that CMB was not so serious as to influence the relationship between variables.

4.2 Hypothesis Testing

Table 2 contains the means, standard deviations, and correlations of all variables. The correlations were consistent with the hypotheses we proposed: loneliness was positively related to stress (γ = .381, p < .001) and depression (γ = .517, p < .001), and negatively related to one’s self-efficacy (γ = −.299, p < .001) and life satisfaction (γ = −.166, p < .001).

Hypothesis 1 predicted loneliness was positively related to stress; as shown in Model 2 Table 3, loneliness positively influenced students’ stress (β = .297, p < .001), thus supporting hypothesis 1. Hypothesis 2 stated loneliness was positively related to depression; as shown in Model 4 Table 3, loneliness positively influenced depression (β = .833, p < .001), thus supporting hypothesis 2. Hypothesis 3 proposed loneliness was negatively associated with life satisfaction. As shown in Model 6 Table 3, loneliness negatively influenced life satisfaction (β = −.200, p < .01), thus supporting hypothesis 3.

According to Baron and Kenny’s (1986) recommendations, we examined the related mediation hypotheses. Hypothesis 4 stated that self-efficacy mediated the relationship between loneliness and stress, depression, and life satisfaction. Results in Model 1 Table 3 showed that loneliness was negatively associated with self-efficacy (β = −.349, p < .001). Moreover, when we regressed stress, depression, and life satisfaction on loneliness and self-efficacy, the effect of loneliness on stress (β = .242, p < .001) and depression (β = .765, p < .001) was reduced; the effect of loneliness on life satisfaction (β = .018, ns) became insignificant, and self-efficacy was negatively related to stress (β = −.160, p < .001) and depression (β = −.195, p < .01) and positively related to life satisfaction (β = .624, p < .001). These results indicated that self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between loneliness and stress as well as depression. Moreover, it fully mediated the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction. Thus, hypothesis 4a, 4b, and 4c were supported.

Preacher and Hayes (2004) noted that Baron and Kenny’s (1986) regression method would possibly result in type I or type II errors, so we used the Sobel test (1982) and MCMAM (Monte Carlo Method for Assessing Mediation; Selig and Preacher 2008) to show the significance and confidential interval of the indirect effect in mediation models in Table 4. The results of the Sobel test revealed that the indirect effect of model 1 was .056 (t = 4.178, p < .001), the indirect effect of model 2 was .068 (t = 3.027, p < .01), and the indirect effect of model 3 was −.218 (t = −5.641, p < .001). We also applied MCMAM to evaluate the indirect effects of the models. The 95 % confidence interval in model 1, 2, and 3 indicated that the indirect effects of three mediation models were significant (model 1, [.032, .084]; model 2, [.027, .116]; model 3, [−.295, −.144], respectively).

5 Discussion

5.1 Theoretical and Practical Implications

The current study was designed to examine the main effect of loneliness on SWB (i.e., stress, depression, and life satisfaction) as well as the mediation of self-efficacy for this relationship in the Chinese context. The results showed that loneliness was a significant predictor of high stress and depression, and low self-efficacy and life satisfaction. Another finding of this study was that self-efficacy mediated the relationship between loneliness and stress, depression, and life satisfaction. In other words, lonely people are more likely to engage in low self-efficacy, which in turn leads to an increase in their stress and depression and a decrease in life satisfaction. Our work contributed to the current literature in the following ways.

First, we examined the relationship between loneliness and students’ stress, depression, and life satisfaction in Chinese context and made a contextual contribution for understanding the loneliness and SWB in a collectivistic and Confucian society. The Chinese usually pay more attention to social relationships and social interaction (Li et al. 2014). As lonely people lack satisfying social relationships and have little social support to cope with the environment, they are more likely to suffer stress. Moreover, lonely people in a collectivism context react more strongly to the deprivation of necessary social ties regarding it as a loss of self-identity resulting in depression. Furthermore, the Chinese treasure relationship harmony (Chen 2002), and social relationships play an indispensable part of their life, so lonely people who suffer social isolation will surely feel less life satisfaction. Moreover, we found that loneliness which indicates the deficiencies in social interaction and isolation from social support network had stronger effects on negative indicators of SWB such as stress, depression, but weaker effect on positive indicators of SWB such as life satisfaction.

Second, by examining the mediation of self-efficacy on the relationship between loneliness and individuals’ stress, depression, and life satisfaction, the present study added new knowledge of cognitive processes between Chinese students’ loneliness and their stress, depression, and life satisfaction. Our findings confirmed that self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between loneliness and stress as well as depression, but fully mediated the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction. We argue that lonely people who encounter social isolation not only have less social support to cope with the environment, but also have less competence to deal with the task and handle the situation, so they suffer higher stress and depression and have lower life satisfaction. We contribute a cognitive explanation to the relationship between loneliness and students’ SWB. Surprisingly, we found that self-efficacy played a very important role between loneliness and life satisfaction because it fully mediated the relationship between them and the indirect effect was relatively high (r = −.218, p < .001), but in cases of stress and depression, even though self-efficacy mediated the relationship between loneliness and stress and depression, the direct effect of loneliness on stress as well as depression were still strong and the indirect effect between them were relatively low (r = .056, p < .001; r = .068, p < .01, respectively). We speculate that self-efficacy which is the positive belief about one’s ability explains the psychological mechanism between loneliness and one’s positive indicators of SWB much better and the psychological mechanism between loneliness and positive and negative indicators of SWB may be different.

This study also provides important practical implications. The findings indicate that loneliness can significantly influence individuals’ SWB, so it is imperative that enough attention be drawn to alleviate lonely people’s negative feelings and provide them with more social support. Furthermore, self-efficacy should be underscored when considering the influence of loneliness on SWB. As self-efficacy is the belief about one’s capabilities to reach certain goals, it is important to enhance lonely people’s beliefs about their abilities when trying to help them feel better about their life and improve their ability to deal with pressure.

5.2 Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations in the current study should be addressed. First of all, despite the test results showing that CMB was not a serious problem in the current study, the data collection procedure still undermined the conclusions we drew. Second, as we used cross-sectional data to test the hypotheses, the cross-sectional nature of these analyses does not permit claims of causal influence. Third, as the participants of this study are students in a business school, the sample’s representativeness of the Chinese context as a whole is limited, which restricts the external validity of the findings.

Further research is therefore recommended in the following ways. First, longitudinal or experimental research design and multiple resources for evaluation should be used to ensure the internal validity and minimize the possibility of CMB. Second, different samples in various contexts and across different age groups need to be examined to extend the external validity of the findings. Moreover, as the study was conducted in China, the generalizability of this work to other individualistic countries is still not clear. A cross-cultural design is thus recommended to ensure the generalizability of the findings. Third, in light of the mediating role played by self-efficacy, we suggest that more attention should be paid to the cognitive and affective process of loneliness and its consequences. Especially, for the process between loneliness and the negative consequences, we should explore more effective mediators to explain their mechanism.

6 Conclusion

Even though there are many studies that have examined the relationship between loneliness and the individual’s subjective well-being, there are still two theoretical gaps in the existing research that we need to understand. One is that the influence of loneliness on one’s SWB is still insufficiently highlighted in the Chinese context which features Confucianism and collectivism. The other one is that the psychological mechanism between loneliness and subjective well-being is still unclear. To fill these two gaps, we explored the relationship between loneliness and individual stress, depression, and life satisfaction in the survey of 444 Chinese undergraduates. The results showed that loneliness was positively related to individual stress and depression, but negatively related to individual life satisfaction. Self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between loneliness, stress and depression, and fully mediated the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction. The present study contributed to the existing studies in two aspects. One is the contextual contribution of extending the research of the relationship between loneliness and stress, depression and life satisfaction into the Chinese context, and the other is this study provides a scope of the cognitive processes between Chinese students’ loneliness and their stress, depression, and life satisfaction.

References

Abbey, A., & Andrews, F. M. (1985). Modeling the psychological determinants of life quality. Social Indicators Research, 16(1), 1–34.

Alkire, S. (2005). Subjective quantitative studies of human agency. Social Indicators Research, 74(1), 217–260.

Alpass, F. M., & Neville, S. (2003). Loneliness, health and depression in older males. Aging & Mental Health, 7(3), 212–216.

Ang, C. S., Mansor, A. T., & Tan, K. A. (2013). Pangs of loneliness breed material lifestyle but don’t power up life satisfaction of young people: The moderating effect of gender. Social Indicators Research, 117(2), 1–13.

Azam, W. M., Yunus, W. M., Din, N. C., Ahmad, M., Ghazali, S. E., Ibrahim, N., et al. (2013). Loneliness and depression among the elderly in an agricultural settlement: Mediating effects of social support. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 5(1), 134–139.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117–148.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bartolini, S., Bilancini, E., & Pugno, M. (2013). Did the decline in social connections depress Americans’ happiness? Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 1033–1059.

Bedford, O., & Hwang, K. (2003). Guilt and Shame in Chinese Culture: A cross-cultural framework from the perspective of morality and identity. Journal For The Theory Of Social Behaviour, 33(2), 127–144.

Beehr, T. A., Jex, S. M., Stacy, B. A., & Murray, M. A. (2000). Work stressors and coworker support as predictors of individual strain and job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(4), 391–405.

Bodenmann, G., Meuwly, N., Bradbury, T. N., Gmelch, S., & Ledermann, T. (2010). Stress, anger, and verbal aggression in intimate relationships: Moderating effects of individual and dyadic coping. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(3), 408–424.

Braveman, P. A., Egerter, S. A., & Mockenhaupt, R. E. (2011). Broadening the focus: The need to address the social determinants of health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40(1), 4–18.

Brief, A. P., Butcher, A. H., George, J. M., & Link, K. E. (1993). Integrating top-down and bottom-up theories of subjective well-being: The case of health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 646–653.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Methodology (pp. 389–444). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Busseri, M. A., & Sadava, S. W. (2011). A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: Implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 290–314.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M., Berntson, G. G., Nouriani, B., et al. (2006). Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(6), 1054–1085.

Cai, H., Wu, Q., & Jonathon, B. D. (2009). Is self-esteem a universal need? Evidence from The People’s Republic of China. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 12(2), 104–120.

Caprara, G. V., & Steca, P. (2005). Self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of prosocial behavior conducive to life satisfaction across ages. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(2), 191–217.

Caron, J. (2012). Predictors of quality of life in economically disadvantaged populations in Montreal. Social Indicators Research, 107(3), 411–427.

Chen, G. M. (2002). The impact of harmony on Chinese conflict management. In G. M. Chen & R. Ma (Eds.), Chinese conflict management and resolution (pp. 3–17). Westport, CONN: Ablex.

Chen, S. X., Cheung, F. M., Bond, M. H., & Leung, J. P. (2006). Going beyond self-esteem to predict life satisfaction: The Chinese case. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 9(1), 24–35.

Chen, X., Wang, P., Wegner, R., Gong, J., Fang, X., & Kaljee, L. (2014). Measuring social capital investment: Scale development and examination of links to social capital and perceived stress. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0611-0.

Cheng, C., Jose, P. E., Sheldon, K. M., Singelis, T. M., Cheung, M. L., Tiliouine, H., et al. (2011). Sociocultural differences in self-construal and subjective well-being: A test of four cultural models. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(5), 832–855.

Cheung, F. M., Leung, K., Zhang, J., Sun, H., Gan, Y., Song, W., et al. (2001). Indigenous Chinese personality constructs: Is the five-factor model complete? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(4), 407–433.

Chioqueta, A. P., & Stiles, T. C. (2005). Personality traits and the development of depression, hopelessness, and suicide ideation. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(6), 1283–1291.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396.

Coutinho, S. (2008). Self-efficacy, metacognition, and performance. North American Journal of Psychology, 10(1), 165–172.

Cramm, J., Strating, M., Roebroeck, M., & Nieboer, A. (2013). The importance of general self-efficacy for the quality of life of adolescents with chronic conditions. Social Indicators Research, 113(1), 551–561.

Diener, E. (2009). The science of well-being. New York: Springer.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E., Scollon, C. N., & Lucas, R. E. (2009). The evolving concept of subjective well-being: The multifaceted nature of happiness. In E. Diener (Ed.), Assessing well-being (pp. 67–100). Netherlands: Springer.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Eid, M., & Larsen, R. J. (Eds.). (2008). The science of subjective well-being. New York: Guilford Press.

Gerich, J. (2013). Effects of social networks on health from a stress theoretical perspective. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0423-7.

Hallion, L. S., & Ruscio, A. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of the effect of cognitive bias modification on anxiety and depression. Psychological Bulletin, 137(6), 940–958.

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227.

Hawkley, L. C., Masi, C. M., Berry, J. D., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2006). Loneliness is a unique predictor of age-related differences in systolic blood pressure. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 152–164.

He, D., Shi, M., & Yi, F. (2013). Mediating effects of affect and loneliness on the relationship between core self-evaluation and life satisfaction among two groups of chinese adolescents. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0508-3.

Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695–718.

Heller, D., Watson, D., & Ilies, R. (2004). The role of person versus situation in life satisfaction: A critical examination. Psychological Bulletin, 130(4), 574–600.

Hermann, K. S., & Betz, N. E. (2006). Path models of the relationships of instrumentality and expressiveness, social self-efficacy, and self-esteem to depressive symptoms in college students. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(10), 1086–1106.

Hsiao, F., Klimidis, S., Minas, H., & Tan, E. (2006). Cultural attribution of mental health suffering in Chinese societies: The views of Chinese patients with mental illness and their caregivers. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(8), 998–1006.

Huo, Y., & Kong, F. (2013). Moderating effects of gender and loneliness on the relationship between self-esteem and life satisfaction in Chinese university students. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0404-x.

Ilhan, T. (2012). Loneliness among university students: Predictive power of sex roles and attachment styles on loneliness. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 12(4), 2387–2396.

Kapıkıran, Ş. (2013). Loneliness and life satisfaction in Turkish early adolescents: The mediating role of self esteem and social support. Social Indicators Research, 111(2), 617–632.

Kong, F., & You, X. (2013). Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Social Indicators Research, 110(1), 271–279.

Kong, F., Zhao, J., & You, X. (2013). Self-esteem as mediator and moderator of the relationship between social support and subjective well-being among Chinese university students. Social Indicators Research, 112(1), 151–161.

Lent, R. W. (2004). Toward a unifying theoretical and practical perspective on subjective well-being and psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(4), 482–509.

Lever, J., Piñol, N., & Uralde, J. (2005). Poverty, psychological resources and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 73(3), 375–408.

Li, Y., Xu, J., Tu, Y., & Lu, X. (2014). Ethical leadership and subordinates’ occupational well-being: A multi-level examination in China. Social Indicators Research, 116(3), 823–842.

Lim, L. L., & Chang, W. C. (2009). Role of collective self-esteem on youth violence in a collective culture. International Journal of Psychology, 44(1), 71–78.

Lischetzke, T., Eid, M., & Diener, E. (2012). Perceiving one’s own and others’ feelings around the world: The relations of attention to and clarity of feelings with subjective well-being across nations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(8), 1249–1267.

Lun, V. M., & Bond, M. H. (2006). Achieving relationship harmony in groups and its consequence for group performance. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 9(3), 195–202.

Luszczynska, A., Gutiérrez-Doña, B., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: Evidence from five countries. International Journal of Psychology, 40(2), 80–89.

Magee, W., & St-Arnaud, S. (2012). Models of the joint structure of domain-related and global distress: Implications for the reconciliation of quality of life and mental health perspectives. Social Indicators Research, 105(1), 161–185.

Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., & Patil, A. (2006). Common method variance in IS research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Management Science, 52(12), 1865–1883.

Mao, Y., Peng, K. Z., & Wong, C. S. (2012). Indigenous research on Asia: In search of the emic components of guanxi. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(4), 1143–1168.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253.

Mathieu, J. E., & Farr, J. L. (1991). Further evidence for the discriminant validity of measures of organizational commitment, job involvement, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(1), 127–133.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1986). Social patterns of distress. Annual Review of Sociology, 12(1), 23–45.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1992). Age and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33(3), 187–205.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (2001). Age and the effect of economic hardship on depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(2), 132–150.

Monat, A., & Lazarus, R. S. (Eds.). (1991). Stress and coping: An anthology. New York: Columbia University Press.

Newall, N., Chipperfield, J., & Clifton, R. (2009). Causal beliefs, social participation, and loneliness among older adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26, 273–290.

Ng, C. S., & Hurry, J. (2011). Depression amongst Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong: An evaluation of a stress moderation model. Social Indicators Research, 100(3), 499–516.

Ostir, G. V., Ottenbacher, K. J., Fried, L. P., & Guralnik, J. M. (2007). The effect of depressive symptoms on the association between functional status and social participation. Social Indicators Research, 80(2), 379–392.

Peplau, L. A., Russell, D., & Heim, M. (1979). The experience of loneliness. In I. H. Frieze, D. Bar-Tal, & J. S. Carroll (Eds.), New approaches to social problems (pp. 53–78). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1984). Loneliness research: A survey of empirical findings. In L. A. Peplau & S. Goldston (Eds.), Preventing the harmful consequences of severe and persistent loneliness (pp. 13–46). DDH Publication: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. M., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method variance in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731.

Rokach, A. (2005a). Drug withdrawal and coping with loneliness. Social Indicators Research, 73(1), 71–85.

Rokach, A. (2005b). Private lives in public places: Loneliness of the homeless. Social Indicators Research, 72(1), 99–114.

Ross, C. E., & Mirowsky, J. (1984). Components of depressed mood in married men and women: The center for epidemiologic studies’ depression scale. American Journal of Epidemiology, 119(6), 997–1004.

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40.

Salimi, A. (2011). Social-emotional loneliness and life satisfaction. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 292–295.

Schunk, D. H. (1989). Self-efficacy and achievement behaviors. Educational Psychology Review, 1(3), 173–208.

Schwabe, L., Wolf, O. T., & Oitzl, M. S. (2010). Memory formation under stress: Quantity and quality. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 34(4), 584–591.

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson.

Selig, J. P. & Preacher, K. J. (2008). Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects. Computer Software. Retrieved from http://www.quantpsy.org

Shea, C. M., & Howell, J. M. (2000). Efficacy-performance spirals: An empirical test. Journal of Management, 26(4), 791–812.

Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J., Ryan, R. M., Chirkov, V., Kim, Y., Wu, C., et al. (2004). Self-concordance and subjective well-being in four cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(2), 209–223.

Shu, X., & Zhu, Y. (2009). The quality of life in China. Social Indicators Research, 92(2), 191–225.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312.

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465.

Strobel, M., Tumasjan, A., & Spörrle, M. (2011). Be yourself, believe in yourself, and be happy: Self-efficacy as a mediator between personality factors and subjective well-being. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 52(1), 43–48.

Sullivan, P. F., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2000). Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(10), 1552–1562.

Swami, V., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Sinniah, D., Maniam, T., Kannan, K., Stanistreet, D., et al. (2007). General health mediates the relationship between loneliness, life satisfaction and depression. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(2), 161–166.

Tharayil, D. P. (2012). Developing the University of the Philippines loneliness assessment scale: A cross-cultural measurement. Social Indicators Research, 106(2), 307–321.

Thoits, P. A. (2013). Self, identity, stress, and mental health. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 357–377). Netherlands: Springer.

Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924.

Ursin, H., & Eriksen, H. R. (2004). The cognitive activation theory of stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(5), 567–592.

Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L., & Lehto, J. E. (2013). Social factors explaining children’s subjective happiness and depressive symptoms. Social Indicators Research, 111(2), 603–615.

Wang, J., Leung, K., & Zhou, F. (2014). A dispositional approach to psychological climate: Relationships between interpersonal harmony motives and psychological climate for communication safety. Human Relations, 67(4), 489–515.

Wang, J., Zhao, J., & Wang, Y. (2013). Self-efficacy mediates the association between shyness and subjective well-being: The case of Chinese college students. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0487-4.

Weeks, D. G., Michela, J. L., Peplau, L. A., & Bragg, M. E. (1980). Relation between loneliness and depression: A structural equation analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1238–1244.

Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by 2014–2015 International Scholar Exchange Fellowship program of Korea Foundation for Advanced Studies and National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 71402127).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

R means reverse coded

-

Loneliness (UCLA Loneliness Scale, Russell 1996)

-

I am in tune with the people around me (R)

-

I lack companionship

-

There is no one I can turn to

-

I feel alone

-

I feel part of a group of friends (R)

-

I have a lot in common with the people around me (R)

-

I am no longer close to anyone

-

My interests and ideals are not shared by those around you

-

I am an outgoing and friendly person (R)

-

I feel close to people (R)

-

I feel left out

-

I feel my relationships with others are not meaningful

-

No one really knows me well

-

I feel isolated from others

-

I can find companionship when I want it (R)

-

There are people who really understand me (R)

-

I feel shy

-

People are around me but not with me

-

There are people I can talk to (R)

-

There are people I can turn to (R)

-

Self-efficacy (Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995)

-

I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough

-

If someone opposes me, I can find the means and ways to get what I want

-

It is easy for me to stick to my aims and accomplish my goals

-

I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected events

-

Thanks to my resourcefulness, I know how to handle unforeseen situations

-

I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort

-

I can remain calm when facing difficulties because I can rely on my coping abilities

-

When I am confronted with a problem, I can usually find several solutions

-

If I am in trouble, I can usually think of a solution

-

I can usually handle whatever comes my way

-

Stress (Cohen et al. 1983)

-

Recently I felt upset because of something that happened unexpectedly

-

Recently I felt that I was unable to control the important things in my life

-

Recently I felt nervous and stressed

-

Recently I dealt successfully with irritating life hassles (R)

-

Recently I felt that I was effectively coping with important changes that were occurring in my life (R)

-

Recently I felt confident about my ability to handle my personal problems (R)

-

Recently I felt that things were going my way (R)

-

Recently I found that I could not cope with all the things that I had to do

-

Recently I was able to control irritations in my life (R)

-

Recently I felt that I was on top of things (R)

-

Recently I was angered because of things that happened that were outside of my control

-

Recently I found myself thinking about things that I have to accomplish

-

Recently I was able to control the way I spend my time (R)

-

Recently I felt difficulties were piling up so high that I could not overcome them

-

Recently I felt I just couldn’t get going

-

Recently I felt sad

-

Recently I had trouble getting to sleep or staying asleep

-

Recently I felt that everything was an effort

-

Recently I felt lonely

-

Recently I felt I couldn’t shake the blues

-

Recently I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing

-

Life satisfaction (Diener et al. 1985)

-

In most ways my life is close to my ideal

-

The conditions of my life are excellent

-

I am satisfied with my life

-

So far I have gotten the important things I want in life

-

If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, Y., Zhang, S. Loneliness and Subjective Well-Being Among Chinese Undergraduates: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy. Soc Indic Res 124, 963–980 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0809-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0809-1