Abstract

Social support protects individuals against adversity throughout the lifespan, and is especially salient during times of intense social change, such as during the transition to adulthood. Focusing on three relationship-specific sources of social support (family, friends, and romantic partners), the current study examined the stress-buffering function of social support against loneliness and whether the association between social support and loneliness with stress held constant would vary by its source. The role of gender in these associations was also considered. The sample consisted of 636 ethnically diverse college youth (age range 18–25; 80 % female). The results suggest that the stress-buffering role of social support against loneliness varies by its source. Only support from friends buffered the association between stress and loneliness. Further, when stress was held constant, the association between social support and loneliness differed by the sources, in that support from friends or romantic partners (but not from family) was negatively associated with loneliness. Regarding gender differences, the adverse impact of lower levels of familial or friends’ support on loneliness was greater in females than in males. This research advances our understanding of social support among college-aged youth; implications of the findings and directions for future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

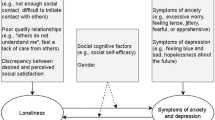

Decades of research have shown that social support benefits individual well-being (Kuwert et al. 2014; Kwag et al. 2011) and may intervene in the association between stress and distress (Lakey and Cohen 2000; Rafaelli et al. 2012; Thoits 2011). Most of the prior research on social support has assessed its aggregate indices (general or global social support), with less attention given to its source (support derived from a specific relationship). However, research on the source of support (relationship-specific support) is essential (Rafaelli et al. 2012; Uchino 2009) in order to best understand its meanings and mechanisms, and its changing implications throughout development. In addition, when considering the implications of stress and/or social support, previous studies have primarily focused on physical and/or psychological health (e.g., Auerbach et al. 2011; Finch and Vega 2003; Vaughan et al. 2010), devoting less work to adversities in social or interpersonal relationships such as feelings of loneliness.

Social and relational challenges are critical to consider, as empirical evidence has shown that both stress and social support are associated with loneliness. For example, Mahon et al. (2006) suggested that stresses associated with social forces outside the individuals, such as social mobility, contribute to loneliness. Hawkley et al.’s (2008) study found that people experiencing higher levels of stress are likely to be disproportionately represented among lonely individuals. Nicpon et al. (2006–2007) found that individuals reporting greater perceived social support also reported less loneliness. Further, loneliness is a risk factor for a number of physical and psychological health problems, including reduced immunity, elevated blood pressure, depressive symptoms, alcoholism, and suicide ideation (Hawkley et al. 2008). Loneliness is also associated with increased risk for early mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2015; Patterson and Veenstra 2010). To begin to address these gaps in the literature, the purpose of the current study is to examine the role of social support in the association between stress and loneliness. In particular, we explore whether the association between stress and loneliness may vary based on perceptions of support from three different relationship contexts: family, friends, and romantic partners. Additionally, we explore whether gender is a factor in individuals’ experiences, given the well-established gender differences in relationships, perceptions, and behaviors (e.g., Hall 2011). In particular, we examine whether gender moderates the associations between sources of social support and loneliness. These issues are explored in a large, ethnically diverse sample of college youth.

Loneliness: A Pervasive Experience Among College Youth

Loneliness is considered a subjective, unpleasant, and emotionally distressing experience that most, if not all, individuals experience at one time or another (Koenig and Abrams 1999; Peplau and Perlman 1982; Qualter et al. 2015). Although loneliness is salient at all developmental stages, researchers have noted that late adolescence and young adulthood are the two life stages during which loneliness is arguably the most prevalent across individuals’ life span (Qualter et al. 2015). This is not surprising, as peer relationships (relationships with friends or intimate partners) play a prominent role among adolescents and young adults. In addition, given that many high school students today choose to go to college immediately after graduation, the transition to college often entails stepping away from long standing intimate relationships in one’s hometown and school. This physical separation from family and friends may result in the termination and/or transitions of close relationships, and/or a discrepancy between desired an achieved social contact. Therefore, the environmental change from high school to college and the developmental needs for social relationships, particularly the need for intimate friendships (Arnett 2015a), may trigger many college youth’s strong desires to be with other people (Qualter et al. 2015). However, if the correspondent changes in actual relationships are not accompanied to fulfill the desires, feeling lonely may be inevitable (Levesque 2011a).

Sources of Social Support on Individual Well-Being

Research on relationship-specific sources of social support is essential (Rafaelli et al. 2012; Uchino 2009) and tends to be based on perceptions of past experiences with specific others (Pierce et al. 1991). Support from varying relationships may exert influences on well-being in different ways for different life stages with regard to developmentally salient focal relationships (Segrin 2003; Sheets and Mohr 2009). The life course perspective views the transition to young adulthood with a focus on the interplay between developmental trajectories and social pathways (Elder 1998; Meadows et al. 2006). Given its emphasis on contexts (Wheaton and Clark 2003), the perspective suggests that, as individuals transition across life stages, both social support and stress may change. Over time, the salience of a given relationship evolves; thus, the impact of support from that relationship on health outcomes is dynamic as well (Umberson et al. 2010). For instance, during adolescence, friends gradually replace parents as the main source of social support and intimacy (Frey and Rothlisberger 1996; Scholte et al. 2001). As individuals transition to adulthood, romantic relationships become more common and important (Arnett 2015a; Markiewicz and Doyle 2011; Qualter et al. 2015). In other words, friends and/or intimate partner support begins to usurp the function of family support as individuals transition to adulthood (Meadows et al. 2006; Tanner 2011). During young adulthood, social support from family members is less effective than support from friends at reducing psychosocial distress (Segrin 2003). Despite this evidence, research also has demonstrated that parental and family support remains critical in promoting young adults’ adjustment and well-being, including social or interpersonal relationships (Lee et al. 2015; Mounts et al. 2006). Although these findings may seem contradictory, this is not necessarily the case. Family support may retain value during young adulthood (Arnett 2015b; Lee et al. 2015), but when compared directly with the support from friends and romantic partners (with whom the youth are likely to spend the most time, and with whom youth may prefer to self-disclose and/or consult about life choices and decision) (Collins and van Dulmen 2006), its relative salience may not be as high during this time of relationship transition (Buhrmester 1996; De Goede et al. 2009; Tanner 2011). Given these patterns, it is clear that research focusing on social support and its impacts on well-being during young adulthood should assess distinct relationship-specific sources of support (Rafaelli et al. 2012).

Buffering Role of Sources of Social Support on Stress and Loneliness

The stress-buffering model (Cohen and Wills 1985; Uchino 2004) asserts that social support functions as a buffer to mitigate the pathogenic effects of stress on individual well-being. In other words, social support helps individuals maintain or regain strengths, particularly when they are under stress or encountering stressful life events, and thereby decreases the potentially detrimental consequences of stress (Ensel and Lin 1991; Thoits 2011; Wheaton 1985). As indicated above, research examining the stress-buffering hypothesis has focused on general social support as the buffer and physical or psychological well-being as outcomes, with very little attention directed toward sources of support and social well-being, such as loneliness. Given the assertion that general social support and sources of social support are two distinct constructs (Pierce et al. 1991), it is tenable that the stress-buffering effect of social support on individuals’ well-being might vary by the sources of support (relationship-specific support providers). In a sample of college students, for example, Crockett et al. (2007) found that, when both parental and peer supports were considered in the same model, only parental support buffered the association between acculturative stress and depressive symptoms. However, to the best of our knowledge, research is scant examining the differential associations of varying sources of social support on the impact of stress on individuals’ social well-being, thereby warranting exploration. These issues are especially germane during the transition to adulthood, given the increased salience of peer relationships (including friendships and romantic partners) (Arnett 2015a). It might be that these relationships have increased importance for predicting well-being and for buffering against psychosocial challenges. Alternatively, given the sometimes fleeting nature of non-familial relationships during this developmental period, it may be that family-based support continues to exert a lasting influence (Lee et al. 2015).

Independent Associations of Sources of Social Support with Loneliness

Stress, social support, and psychosocial well-being have complicated interconnections. As noted above, it is well documented that social support can offset the adverse impact of stress on a variety of adjustment indices. It is also possible, however, for stress to provoke the deterioration of social support for troubled individuals, given the impact of stress on their access to and willingness to enlist supportive assistance (Thompson et al. 2006). In other words, stress may be related to diminished, rather than enhanced, social support (Kwag et al. 2011).

In contrast, the independent model proposed by Ensel and Lin (1991) suggests that social support may benefit individuals through promoting their well-being, or by safeguarding them against distress by providing positive affect, material resources, and/or a recognition of self-worth, regardless of the level of stress present. Wheaton (1985) illustrates that social support is an independent distress deterrent. Conversely, perceiving lack of social support may increase the likelihood of distress, for example, by feeling lonely (Segrin 2003). There is considerable empirical evidence supporting the independent model. A number of studies have consistently shown that holding stress constant, perceiving greater social support alleviates loneliness (e.g., Aanes et al. 2009; Bancila et al. 2006; Bishop and Martin 2007; Cacioppo et al. 2006; Kuwert et al. 2014; Kwag et al. 2011). However, most of these studies were based on older adults, with little effort devoted specifically to youth transitioning to adulthood. Given the aforementioned challenges with social connection that sometimes occurs in this age group, this is a concern. In addition, all of these studies investigated general social support. Researchers have not applied the independence model when examining whether the association between social support and loneliness may vary by the source of support.

Below we briefly review the current literature on the associations between sources of social support and loneliness. In general, stress has not been considered in previous research, and findings have been somewhat inconsistent. For example, Pierce et al. (1991), in a sample of undergraduate students, suggested that support from friends was a better predictor of loneliness than support from family/parents or romantic partners. Using adult samples, Segrin and colleagues (Segrin 2003; Segrin and Passalacqua 2010) found that higher levels of social supports from family, friends, and a significant other each were associated with lower levels of loneliness. However, the three sources of support were not examined concurrently in their studies, despite the high correlations among them. Jones and Moore (1990) surveyed youth during their beginning semester in college and found that although support from friends was negatively related to levels of loneliness, support from family was positively associated with loneliness, meaning those with higher levels of family support felt lonelier than those with lower levels of family support. A similar finding of a positive relationship between family support and loneliness was reported in Eshbaugh’s (2010) study using a sample of college women living in the university’s residence halls. Findings from these two studies suggest that those with a strong support system at home may be vulnerable to feeling isolated and lonely when separated from family, even when the separation is due to attending college. Further, there were studies using college youth and considering only one particular source of support (family, friends, or romantic partners) when examining the association between social support and loneliness (e.g., Larose et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2015; Mounts 2004; Mounts et al. 2006; Ozdemir and Tuncay 2008). The results of these studies all suggest that the association between the particular source of support considered and loneliness is negative. Thus, in order to further our understanding of the relative salience among various sources of support in their associations with loneliness, future research not only should include stress as a covariate, but also should pay more attention to differentiating support from different sources.

Gender Differences

Research has shown that there are gender differences in youth’s early socialization pertaining to social relationships. From an early age, parents provide gender-specific relationship socialization for their daughters and sons. Intimate relationships, and associated emotions, are emphasized in girls’ early socialization and deemphasized in boys’ (e.g., Eisenberg and Fabes 1994; Shipman et al. 2003); thus, it is not surprising that, by adolescence and young adulthood, clear gender differences exist with regard to perceptions of, and experiences with, intimate relationships (Hall 2011; Shulman and Scharf 2000). Interestingly, however, with regard to gender differences on loneliness, it remains unclear, as mixed findings have been reported during these two developmental stages (Koenig and Abrams 1999; Schinka et al. 2013). For example, based on samples of adolescents or young adults (mostly college students), research has found that boys or men are lonelier (e.g., Mounts 2004; Roux 2009; Subrahmanyam and Lin 2007) or less lonely (e.g., McWhirter 1997; Prezza et al. 2004) than girls or women, or that the levels of loneliness do not differ by gender (e.g., Ilhan 2012; Lasgaard et al. 2011; Stoliker and Lafreniere 2015). Mahon et al. (2006), in their meta-analytic study (the age of study samples ranging from 11 to 23 years in the studies reviewed), found a similar inconsistency on the association between gender and loneliness. However, most of the studies they reviewed have reported non-significance, suggesting no gender differences on loneliness.

On the other hand, little is known about whether the associations between sources of support and loneliness might vary by gender. Research to examine such a potential gender effect, especially among young adults, is warranted, as previous studies have suggested that girls in general devote more time and energy on developing friendships and value close friendships more than boys during adolescence (Bowker and Ramsay 2011; Levesque 2011b; Rafaelli and Duckett 1989), and that women overall perceive higher levels of social support than men during young adulthood (Adamczyk 2015; Weckwerth and Flynn 2006). Although women, as compared to men, seem to benefit more from support provided by parents and close friends, they also tend to suffer more from the effects of a lack of such support (Sifers 2011). Thus, perceiving lower levels of support from family or friends, for example, might lead to increases in loneliness more in female than in male college youth, given a possible greater discrepancy between desired and achieved levels of social contact among females. However, very few studies have empirically examined such gender moderation effects. Although scarce, the findings have provided support for the notion. For example, Zhang, Gao, Fokkema, Alterman, and Liu (2015), in their sample of late adolescents, found that the negative association between perceived social support, particularly support from friends and romantic partners, and loneliness was greater for girls than for boys. Similar results were found in Koenig and Abrams’ (1999) study, which also used an adolescent sample, yet focused only on friends’ support. To our best knowledge, no research has examined gender moderation in the association between perceived family support and loneliness or used samples of youth transitioning to adulthood to investigate whether gender moderation may differ by the sources of social support.

The Current Study

Using a large and diverse sample of college-aged youth, the purpose of the present study is to extend the current research on social support by examining its associations with loneliness. Three specific sources of support are considered, including support from the primary socialization agents of young adulthood: families, friends, and romantic partners. Gender differences regarding loneliness and its potential moderating role in the relationships between sources of social support and loneliness are also explored. Although the number of people going to college has increased substantially over the past few decades, the percentage of students persisting and graduating from college within four years is still low (Arnett 2015b; Brock 2010). Such interruptions or failure in academic accomplishments may be attributed in part to stress-related problems and/or struggles in social relationships that many college students experience, such as loneliness (Nicpon et al. 2006–2007). Thus, in order to promote success in college and social adjustment in college life, it is both essential and urgent to examine whether social support might help alleviate students’ feelings of loneliness and if so, whether the positive role of social support might differ by its sources. The findings of this study will advance our understanding of the association between social support and loneliness in college youth, especially the relative salience of three distinct sources of support, as well as whether the relationships might vary by gender.

Based on the research discussed above, we have four hypotheses. First, we hypothesize that the role of social support as a buffer of stress against loneliness will differ by its particular sources (family, friends, and romantic partner). Specifically, because the focal age point of the study is college-aged youth, we hypothesize that support from friends and romantic partners will provide the strongest protection against loneliness. Second, we hypothesize that the independent association of social support with loneliness differs by its particular sources (family, friends, and romantic partner). In particular, we predict that social support from friends and romantic partners will have the most robust negative associations with loneliness—as support from friends and romantic partners increases, loneliness will decrease.

The third and fourth hypotheses pertain to gender differences. Although we do not predict any gender difference in mean levels of loneliness (hypothesis 3), we expect that the moderating role of gender in the association between social support and loneliness will differ by the sources of support (family, friends, and romantic partner). Specifically, it is anticipated that females will be particularly sensitive to levels of support provided by each of the three relationship sources, as compared to males.

Method

Procedure and Participants

After receiving approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), a survey was administered to undergraduate students at a mid-sized public university in the Northeast region of the United States. Participants were recruited in a variety of ways, including email, flyers, and word of mouth, and surveys were conducted in a variety of campus locations, including classrooms, dormitories, student centers, and student organization meetings. All data were collected in person, and participants received a $5 incentive for completing the survey.

The sample consisted of 636 undergraduate students from various disciplines, such as human development, family studies, psychology, biology, exercise science, and English (80 % female and 20 % male). The average age was 19.8 years (SD = 1.5; Range = 18–25), with 36.8 % freshmen, 22.6 % sophomore, 25.2 % junior, and 15.1 % senior. Two individuals did not identify their school year. About half of the participants (337; 53 %) self-identified as White, 138 (21.7 %) as Hispanic, 85 (13.4 %) as Black or African-American, 23 (3.6 %) as Asian-American, 41 (6.4 %) as multiracial, and 12 (1.9 %) as other. The range and proportions of participants’ ethnicity or race are representative of the campus where the study was conducted.

Instruments

Perceived Stress

Perceived stress was assessed by the 10-item shorter version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10; Cohen and Williamson 1988). The scale measures the degree to which situations in an individual’s life are appraised as stressful. Using a probability sample of individuals ages 18 or more, Cohen and Williamson (1988) found that the PSS-10 had adequate psychometric qualities (e.g., internal reliability with a coefficient alpha of .78 and concurrent validity via a positive correlation with a life-events scale and negative correlation with self-reported physical health). Despite its high correlation with depressive symptomology, the scale was found to measure a different and independently predictive construct. Respondents were asked to indicate, using a 5-point scale (0 = never, 4 = very often), how often during the past month they felt or thought a certain way, such as being upset because something that happened unexpectedly, being unable to control the important things in their lives, and difficulties being piling up so high that they could not overcome them. Mean ratings of the 10 item responses were used, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress (α = .81 in the current study).

Sources of Social Support

Sources of social support were measured by the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al. 1988), which consists of 12 items assessing three particular sources of social support: Family, Friends, and Romantic Partners (four items per source of support). Zimet et al. (1988) used undergraduate college youth in their study, reporting coefficient alphas of .87, .85, and .91 for the support subscales of family, friends, and romantic partners, respectively. Test–retest reliability over a 2–3 month interval was also reported (85, .75, and .72 for the support subscales of family, friends, and romantic partners, respectively). Construct validity of the scale has been established in the study through its negative correlations with depression and anxiety symptomatology measured by the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (Derogatis et al. 1974). The respondents indicated to what extent they agreed with each statement using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Sample items include, “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family” (support from family), “I can count on my friends when things go wrong” (support from friends), and “There is a special person with whom I can share my joys and sorrows” (support from romantic partner). None of the items measuring support specify the mechanism through which support was delivered (e.g., in-person or online); rather, support for the various relationships could have occurred in a variety of contexts and was left up to the participants to interpret. The mean score of each subscale for the source of support was calculated, with higher scores indicating higher levels of the particular sources of support. Cronbach’s αs for this study were .92, .93, and .93 for the support subscales of family, friends, and romantic partners, respectively.

Loneliness

Loneliness was evaluated by the 8-item short-form of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (UCLA-8; Hays and DiMatteo 1987). Participants rated how often they felt the way described in each of the eight statements (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often). Sample statements are “I feel isolated from others” and “I lack companionship.” Mean scores were calculated so that higher scores signify higher levels of loneliness. Hays and DiMatteo (1987) reported a coefficient alpha of .84 for the scale’s internal consistency and provided evidence of its construct validity via positive correlation with personality characteristics such as alienation and social anxiety. Cronbach’s α for the current study was .83.

Results

Analysis Strategy

All analyses were conducted using SPSS (21.0). We tested both stress-buffering and independent relationships of social support with loneliness by running a series of hierarchical multiple regressions. Table 1 presents the correlation matrix with means and standard deviations for the focal predictors, moderator variables, criterion variable, and control variables in the study. Despite the mixed results on whether gender and ethnicity are associated with loneliness (Mahon et al. 2006; Schinka et al. 2013), they were included in the analyses as covariates, because prior research and/or our data have shown their correlations with the study variables. For example, Adamczyk (2015) found that women overall perceived higher levels of social support than men during young adulthood. In our data, gender was correlated with all three sources of support, and ethnicity was related to loneliness (see Table 1). For all moderation analyses in the study, both the focal predictor (perceived stress or sources of social support) and the proposed moderator variable (sources of social support or gender) were centered before analysis to reduce problems associated with multicollinearity (Frazier et al. 2004). During the analyses, controlling variables were entered first, followed by the focal predictor and the proposed moderator(s) as the second step, and the interaction term(s) (the product of predictor and moderator) as the third step. In particular, to examine the role of individual source of social support as a buffer of stress against loneliness, we tested a model of multiple additive moderation due to the high correlations among the three sources of support in our data (Hayes 2013). Multiple-moderator models allow for the examination of several moderators concurrently, and the results will indicate the relative salience among the moderators in the relationships under investigation. Whether the independent association between social support and loneliness would differ by the sources of support was tested with hierarchical multiple regression by entering the controlling variables first, followed by the stress variable and the three sources of social support variables. Finally, an independent-samples t test was employed to investigate the gender difference on the levels of loneliness.

Table 2 presents the results of the stress-buffering test (the multiple-moderator model). We found that among the three sources of social support, only support from friends (B = −.07, SE = .03, β = −.10, t = −2.72, p = .007, 95 % CI [−.12, −.02]) was a moderator, buffering the association between perceived stress and loneliness. Following the guideline provided by Aiken and West (1991) for interpreting moderation results, we found that the association between perceived stress and loneliness is less detrimental for those with higher levels of friends support than those with lower levels.

In terms of the relative salience among the three sources of social support in their associations with loneliness, holding the perceived stress constant, the findings suggest that the independent association between social support and loneliness varies by its sources. Specifically, regardless of the levels of stress perceived, supports from friends and romantic partners each had a negative relationship with the levels of loneliness (Bs = −.13 and −.09, SEs = .02 and .02, βs = −.26 and −.19, ts = −6.37 and −4.62, 95 % CIs [−.17, −.09] and [−.13, −.05], respectively, both ps < .001). However, support from family was not an effective factor in its association with the levels of loneliness (B = −.02, SE = .02, β = −.05, t = −1.20, p = .23, 95 % CI [−.06, .01]), when the other two sources of support were in the model.

The results showed no gender difference for loneliness, M male = 2.00, SD male = .65, M female = 1.91, SD female = .62, t(633) = 1.45, p = .15, 95 % CI [−.03, .21]. Although males on average appeared to manifest higher levels of loneliness than females, the observed difference was not statistically significant. In terms of the moderating role of gender on the relationships between sources of social support and loneliness, Table 3 presents the results. As indicated, gender moderated the associations between family support and loneliness (B = −.10, SE = .04, β = −.10, t = −2.80, p = .005, 95 % CI [−.18, −.03]) and between friends support and loneliness (B = −.08, SE = .04, β = −.07, t = −1.99, p = .047, 95 % CI [−.16, −.001]). However, gender did not moderate how romantic partner support was related to loneliness (B = −.05, SE = .04, β = −.05, t = −1.34, p = .18, 95 % CI [−.12, .02]). Following the guidelines provided by Aiken and West (1991) for interpreting moderation results, the negative associations between support from family and loneliness and between support from friends and loneliness were both greater for female than for male college youth.

Discussion

The current study extends research on the role of social support in the association between perceived stress and loneliness by testing two theoretical models—the stress-buffering model and the independent model. Our focus is on three specific sources of social support (family, friends, and romantic partners) to examine their relative salience as moderators and as distress deterrents. We also explore the way in which these patterns of relationships differed for females versus males. These issues are studied in a large and ethnically diverse sample of college youth between the ages of 18 and 25.

The results highlight the differentiating support from three different sources in terms of whether they are different in buffering the association between perceived stress and loneliness and in relating to the levels of loneliness, irrespective of the stress levels, during the transition to adulthood. The stress-buffering or moderation of social support on loneliness was found to vary by the three sources of support. Specifically, only support from friends buffered the association between perceived stress and loneliness. For youth with higher levels of support from friends, the magnitude of the relationship between stress and loneliness was less than those with lower friends support. This pattern of findings provides partial support for our first hypothesis, which predicted that support from both friends and romantic partners would buffer the association between stress and loneliness. Prior research has found that the buffering role of social support varies by its sources in that parental support, not peer support, buffers the adverse association between stress and individuals’ psychological well-being (i.e., depressive symptoms) (Crockett et al. 2007). Therefore, our study has added an important piece to the literature by suggesting that the buffering function of social support against stress on individuals’ social well-being also varies by its sources. Friendships, in particular, served a unique function in the current sample in terms of buffering youth from the challenges of stress. This could have occurred for a number of reasons; for example, perhaps friendships were more emotionally intimate and longer lasting than romantic relationships. Although the current data do not allow for this particular line of follow-up inquiry, it will be interesting for future research to explore these issues in greater detail.

An additional key finding of the current study is that, as an independent distress deterrent, support from friends or romantic partners was particularly beneficial for the college-aged participants in the current study given its relationship to lower levels of loneliness, regardless of the level of stress. Support from families, in contrast, was not associated with loneliness. These results were consistent with our second hypothesis. However, these findings do not necessarily mean that families are not important for overall well-being during young adulthood. Rather, the current findings may reflect a changing relational focus during this developmental period, with the emphasis shifting from the family of origin to the establishment of close, non-familial ties (Buhrmester 1996; De Goede et al. 2009). In addition, support from friends emerged as the most salient factor in alleviating emerging adults’ loneliness among the three particular sources of support examined in our study. Thus, our study augments previous research focusing on the sources of support when researching social support (Azmitia et al. 2013; Rafaelli et al. 2012), and provides additional evidence that various sources of social support may be associated with individual well-being in different ways among youth transitioning to adulthood. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine these issues with a focus on college youth’s distress in social relationships.

The current findings are consistent with the life course perspective (Elder 1998), which places individuals’ relationships and their meanings within a developmental context. As an individual moves from adolescence and transitions to adulthood, support from friends or peers may be particularly effective in enhancing his or her well-being, and/or reducing levels of distress caused by stress. This knowledge is essential, as the college years are often characterized by considerable stress and relationship transitions (Arnett 2015b). In addition, our findings suggest that particular support from friends is more helpful in buffering the adverse impact of stress on individuals’ social well-being, compared to support from family or intimate partners. Although the negative outcome of stress on individuals’ social relationships may seem inevitable, college-aged youth are encouraged to invest time and effort in developing quality friendships in hopes that they would be less distressed or vulnerable to feeling of loneliness.

The current study also contributes to our understanding of gender differences in individuals’ levels of loneliness and the moderating role of gender in the association with social support and loneliness during young adulthood. The literature has shown mixed results for gender differences on loneliness. Although no gender differences emerged with regard to mean levels of loneliness (providing support for our third hypothesis), gender moderated the association between social support and loneliness. Specifically, the negative relationships between family and friends support and loneliness each was greater for female college youth than for their male counterparts. In other words, despite the negative relationships for both genders, perceiving lower levels of support from family or friends was more adversely related to loneliness for females, as compared to males. This pattern of findings provides partial support for our fourth hypothesis, in that females were particularly sensitive to lower levels of support from friends and family members. This is a notable contribution to the literature, and is consistent with previous research regarding gender differences in youth’s relationship experiences and perceptions. For example, Rafaelli and Duckett (1989) have pointed out that female adolescents tend to devote more time and energy to developing social relationships than male adolescents. Similarly, research on conflict and aggression within youth’s peer relationships suggests that females, as compared to males, are more upset by peer altercations and spend more time thinking about them (e.g., Goldstein and Tisak 2004; Paquette and Underwood 1999). Thus, even though a relational focus certainly has many potential upsides, perhaps the increased emphasis on relationships for females puts them at risk for an increased discrepancy between desired and achieved social relationships, thereby intensifying their vulnerability to loneliness (Sifers 2011). Although this was not tested specifically in the present study, it would be interesting to explore these issues in future research.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of this study, there are several limitations that should be noted. First, data were all based on participants’ self reports, which may have contributed to greater associations among the variables due to shared method variance. Second, this study was cross-sectional in design. Thus, no causal inferences can be made. For example, it could be that social support and loneliness are related in a reciprocally interactive fashion (Needham 2008). In other words, low social support may be the outcome, not simply the predictor, of loneliness. Thus, it will be important for future research to employ a longitudinal research design to establish directionality in the relationships proposed in our model. Third, the study sample consisted of only college students; the extent to which results generalize to youth who do not attend college is unclear. Despite the significant increase in the number of individuals attending colleges in recent years (Brock 2010), there are still many people who do not go to college. Non-college-bound youth are underrepresented in research (Arnett 2015b), and differ from their college-bound peers on demographic, socioeconomic, and psychosocial variables (Halperin 2001). Subsequent research should recruit research participants from this understudied population of nonstudents. With regard to a non-student sample, it may be that associations among support and adjustments vary by the reason why youth are not currently in school, perhaps relating to issues such as employment status, living arrangements, or identity status development. An additional concern is that the current data do not allow for assessing the specific interpersonal mechanism through which the support was derived. For example, it may be that perceived face-to-face support is more beneficial as compared to perceived support through online social networking or through a telephone call. This is an important direction for future research to take, as technological advances have altered the day-to-day process of interpersonal interactions. Finally, the current data do not allow for the specification of romantic relationship status. Given the diversity of romantic relationship experiences of college-aged youth, it will be important for future research to assess whether romantic relationship experience, history, or status relates to perceptions of support.

Implications

Despite these limitations, the current study provides insight to the crucial role of social support for promoting well-being during the transition to adulthood. At a time when youth are reestablishing their roles in family and society, they may be particularly vulnerable to feelings of loneliness and isolation. The current findings suggest that some of these concerns, and their links to additional psychosocial distress, can be mitigated by social support from friends, reaffirming the important role of friends support in emerging adults’ adjustment in college (Azmitia et al. 2013). College campuses can respond to this by creating opportunities that increase the likelihood of students developing meaningful interpersonal connections with one another, for example, through efforts such as college-sponsored peer mentoring programs (e.g., Abe et al. 1998), social support group intervention programs (e.g., Mattanah et al. 2010), or group interventions for students who may present with particular challenges, such as international moves and acculturation (e.g., Smith and Khawaja 2014). Participation in clubs and organizations may benefit some students (Weir and Okun 1989), and there is recent evidence that social connection online (such as connecting with college friends through Facebook) can facilitate college students’ social adjustment (Gray et al. 2013). Community and religious groups can also play a role in the establishment of social networks among youth by offering low cost and easily accessible ways to join youth groups, study groups, and other types of peer networks in students’ new college communities, which may be quite a distance from their home bases where these community and religious connections may have already been established. An additional notable point pertains to the gender moderation findings, indicating that perceiving low support from family or friends was particularly deleterious for females. Thus, especially for those parents having daughters in college, it is important that they continue to stay connected with, and make their support available to, their children as they transition to adulthood. During this time period, there is still a need for material (e.g., money), advice, and/or emotional support from families of origin (Arnett 2015b; Collins and van Dulmen 2006), even though peer relationships may provide social support that may be more pivotal for psychosocial adjustment on campus. Finally, given that our results suggested the particularly advantageous role of friendships as compared to other types of relationships for both males and females, youth should be reminded that good friends can still fulfill important relationship functions and are associated with well-being and adjustment, such as higher self-esteem and lower depression and loneliness (Azmitia et al. 2013; Tanner 2011) and that coupling off romantically is not the only way to achieve the benefits of emotional intimacy and companionship.

Conclusion

The college years are an important time of social and relational transition. Previous studies have documented that during the late teens and early twenties, youth move away from primary dependency on their families of origin for intimacy and companionship, and instead begin to turn to friends and romantic partners (Arnett 2015a; Meadows et al. 2006; Tanner 2011). The current study expands on this research, and demonstrates that the social support provided by friends during this time acts as a buffer to some of the negative psychosocial implications of stress. Moreover, a lack of support from friends and romantic partners was related to increases in loneliness, further highlighting the significance of these non-familial relationships in individual well-being during late adolescence and the transition to adulthood. Because loneliness may be at its lifetime peak during the college years (Qualter et al. 2015), these results call attention to the need for increased programmatic and institutional support for relationship development and maintenance during these transitional years. As the current study demonstrates, although there are multiple paths to fulfilling social needs during the transition to adulthood, specific sources of support may be especially beneficial.

References

Aanes, M. M., Mittelmark, M. B., & Hetland, J. (2009). The experience of loneliness: Main and interactive effects of interpersonal stress, social support and positive affect. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 11, 25–33. doi:10.1080/14623730.2009.9721797.

Abe, J., Talbot, D. M., & Geelhoed, R. J. (1998). Effects of a peer program on international student adjustment. Journal of College Student Development, 39, 539–547.

Adamczyk, K. (2015). An investigation of loneliness and perceived social support among single and partnered young adults. Current Psychology,. doi:10.1007/s12144-015-9337-7.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Arnett, J. J. (2015a). Socialization in emerging adulthood: From the family to the wilder world, from socialization to self-socialization. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 85–108). New York: The Guilford Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2015b). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teems through the twenties (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

Auerbach, R. P., Bigda-Peyton, J. S., Eberhart, N. K., Webb, C. A., & Ho, M. H. R. (2011). Conceptualizing the prospective relationship between social support, stress, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 475–487. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9479-x.

Azmitia, M., Syed, M., & Radmacher, K. (2013). Finding your niche: Identity and emotional support in emerging adults’ adjustment to the transition to college. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23, 744–761. doi:10.1111/jora.12037.

Bancila, D., Mittelmark, M. B., & Hetland, J. (2006). The association of interpersonal stress with psychological distress in Romania. European Psychologist, 11, 39–49. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.11.1.39.

Bishop, A. J., & Martin, P. (2007). The indirect influence of educational attainment on loneliness among unmarried older adults. Educational Gerontology, 33, 897–917. doi:10.1080/03601270701569275.

Bowker, A., & Ramsay, K. (2011). Friendship characteristics. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 1080–1086). New York: Springer.

Brock, T. (2010). Young adults and higher education: Barriers and breakthroughs to success. The Future of Children, 20, 109–132. doi:10.1353/foc.0.0040.

Buhrmester, D. (1996). Need fulfillment, interpersonal competence, and the developmental contexts of early adolescent friendship. In W. Bukowski, A. Newcomb, & W. Hartup (Eds.), The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence (pp. 158–185). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Walte, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging, 21, 140–151. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140.

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. M. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health (pp. 31–67). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

Collins, W. A., & van Dulmen, M. (2006). Friendships and romance in emerging adulthood: Assessing distinctiveness in close relationships. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 219–234). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Crockett, L. J., Iturbide, M. I., Torres Stone, R. A., McGinley, M., Raffaelli, M., & Carlo, G. (2007). Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: Relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 347–355. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.347.

De Goede, I., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. (2009). Developmental changes in adolescents’ perceptions of relationships with their parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 75–88. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9286-7.

Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenluth, E. H., & Covi, L. (1974). The Hopskins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19, 1–15. doi:10.1002/bs.3830190102.

Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1994). Mothers’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: Relations to children’s temperament and anger behavior. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 40, 138–156. doi:10.1002/dev.20608.

Elder, G. H. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69, 1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x.

Ensel, W. M., & Lin, N. (1991). The life stress paradigm and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 32, 321–341. doi:10.2307/2137101.

Eshbaugh, E. M. (2010). Friend and family support as moderators of the effects of low romantic partner support on loneliness among college women. Individual Differences Research, 8, 8–16.

Finch, B. K., & Vega, W. A. (2003). Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health, 5, 109–117.

Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. P., & Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 115–134. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115.

Frey, C. U., & Rothlisberger, C. (1996). Social support in healthy adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25, 17–31. doi:10.1007/bf01537378.

Goldstein, S. E., & Tisak, M. S. (2004). Adolescents’ outcome expectancies about relational aggression within acquaintanceships, friendships, and dating relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 283–302. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.007.

Gray, R., Vitak, J., Easton, E. W., & Ellison, N. B. (2013). Examining social adjustment to college in the age of social media: Factors influencing successful transitions and persistence. Computers & Education, 67, 193–207. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2013.02.021.

Hall, J. A. (2011). Sex differences in friendship expectations: A meta-analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28, 723–747. doi:10.1177/0265407510386192.

Halperin, S. (2001). The forgotten half revisited: American youth and young families, 1988–2008. Washington, DC: American Youth Policy Forum.

Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 63B, S375–S384. doi:10.1093/geronb/63.6.s375.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hays, R. D., & DiMatteo, R. (1987). A short-form measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51, 69–81. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 227–237. doi:10.1177/1745691614568352.

Ilhan, T. (2012). Loneliness among university students: Predictive power of sex roles and attachment styles on loneliness. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 12, 2387–2396.

Jones, W. H., & Moore, T. L. (1990). Loneliness and social support. In M. Hojat & R. Crandall (Eds.), Loneliness: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 145–156). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Koenig, L. J., & Abrams, R. F. (1999). Adolescent loneliness and adjustment: A focus on gender differences. In K. J. Rotenberg & S. Hymel (Eds.), Loneliness in childhood and adolescence (pp. 296–322). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kuwert, P., Knaevelsrud, C., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2014). Loneliness among older veterans in the United States: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22, 564–569.

Kwag, K. H., Martin, P., Russell, D., Franke, W., & Kohut, M. (2011). The impact of perceived stress, social support, and home-based physical activity on mental health among older adults. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 72, 137–154. doi:10.2190/ag.72.2.c.

Lakey, B., & Cohen, S. (2000). Social support theory and measurement. In S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood, & B. H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 29–52). New York: Oxford University Press.

Larose, S., Guay, F., & Boivin, M. (2002). Attachment, social support, and loneliness in young adulthood: A test of two models. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 684–693. doi:10.1177/0146167202288012.

Lasgaard, M., Goossens, L., & Elklit, A. (2011). Loneliness, depressive symptomatology, and suicide ideation in adolescence: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 137–150. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9442-x.

Lee, C.-Y. S., Dik, B. J., & Barbara, L. A. (2015). Intergenerational solidarity and individual adjustment during emerging adulthood. Journal of Family Issues,. doi:10.1177/0192513x14567957.

Levesque, R. J. R. (2011a). Loneliness. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 1624–1626). New York: Springer.

Levesque, R. J. R. (2011b). Loners. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 1626–1629). New York: Springer.

Mahon, N. E., Yarcheski, A., Yarcheski, T. J., Cannella, B. L., & Hanks, M. M. (2006). A meta-analytic study of predictors for loneliness during adolescence. Nursing Research, 55, 308–315. doi:10.1097/00006199-200609000-00003.

Markiewicz, D., & Doyle, A. B. (2011). Best friends. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 254–260). New York: Springer.

Mattanah, J. F., Ayers, J. F., Brand, B. L., Brooks, L. J., Quimby, J. L., & Scott, M. W. (2010). A social support intervention to ease the college transition: Exploring main effects and moderators. Journal of College Student Development, 51, 93–108. doi:10.1353/csd.0.0116.

McWhirter, B. T. (1997). Loneliness, learned resourcefulness, and self-esteem in college students. Journal of Counseling & Development, 75, 460–469. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1997.tb02362.x.

Meadows, S. O., Brown, J. S., & Elder, G. H. (2006). Depressive symptoms, stress, and support: Gendered trajectories from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 93–103. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-9021-6.

Mounts, N. S. (2004). Contributions of parenting and campus climate to freshmen adjustment in a multiethnic sample. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 468–491. doi:10.1177/0743558403258862.

Mounts, N. S., Valentiner, D. P., Anderson, K. L., & Boswell, M. K. (2006). Shyness, sociability, and parental support for the college transition: Relation to adolescents’ adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 71–80. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-9002-9.

Needham, B. L. (2008). Reciprocal relationships between symptoms of depression and parental support during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 893–905. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9181-7.

Nicpon, M. F., Huser, L., Blanks, E. H., Sollenberger, S., Befort, C., & Robinson Kurpius, S. E. (2006–2007). The relationship between loneliness and social support with college freshmen’s academic performance and persistence. Journal of College Student Retention, 8, 345–358. doi:10.2190/a465-356m-7652-783r

Ozdemir, U., & Tuncay, T. (2008). Correlates of loneliness among university students. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 2, 29–34. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-2-29.

Paquette, J. A., & Underwood, M. K. (1999). Gender differences in young adolescents’ experiences of peer victimization: Social and physical aggression. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45, 242–266.

Patterson, A. C., & Veenstra, G. (2010). Loneliness and risk of mortality: A longitudinal investigation in Alameda County, California. Social Science and Medicine, 71, 181–186. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.024.

Peplau, L. A., & Perlman, D. (1982). Perspectives on loneliness. In L. A. Peplau & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 1–18). New York: Wiley.

Pierce, G. R., Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (1991). General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: Are two constructs better than one? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 1028–1039. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.6.1028.

Prezza, M., Pacilli, M. G., & Dinelli, S. (2004). Loneliness and new technologies in a group of Roman adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 20, 691–709.

Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., et al. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 250–264. doi:10.1177/1745691615568999.

Rafaelli, M., Andrade, F. C. D., Wiley, A. R., Sanchez-Armass, O., Edwards, L. L., & Aradillas-Garcia, C. (2012). Stress, social support, and depression: A test of the stress-buffering hypothesis in a Mexican sample. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23, 283–289. doi:10.1111/jora.12006.

Rafaelli, M., & Duckett, E. (1989). “We were just talking…”: Conversations in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 18, 567–582. doi:10.1007/bf02139074.

Roux, A. L. (2009). The relationship between adolescents’ attitudes toward their fathers and loneliness: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 219–226.

Schinka, K. C., van Dulmen, M. H. M., Mata, A. D., Bossarte, R., & Swahn, M. (2013). Psychosocial predictors and outcomes of loneliness trajectories from childhood to early adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 1251–1260. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.002.

Scholte, R. H. J., van Lieshout, C. F. M., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2001). Perceived relational support in adolescence: Dimensions, configurations, and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11, 71–94.

Segrin, C. (2003). Age moderates the relationships between social support and psychosocial problems. Human Communication Research, 29, 317–342. doi:10.1093/hcr/29.3.317.

Segrin, C., & Passalacqua, S. A. (2010). Functions of loneliness, social support, health behaviors, and stress in association with poor health. Health Communication, 25, 312–322. doi:10.1080/10410231003773334.

Sheets, R. L., & Mohr, J. J. (2009). Perceived social support from friends and family and psychosocial functioning in bisexual young adult college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 152–163. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.56.1.152.

Shipman, K. L., Zeman, J., Nesin, A. E., & Fitzgerald, M. (2003). Children’s strategies for displaying anger and sadness: What works with whom? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 100–122. doi:10.1353/mpq.2003.0006.

Shulman, S., & Scharf, M. (2000). Adolescent romantic behaviors and perceptions: Age- and gender-related differences, and links with family and peer relationships. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 10, 99–118. doi:10.1207/sjra1001_5.

Sifers, S. K. (2011). Social support. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 2810–2815). New York: Springer.

Smith, R. A., & Khawaja, N. G. (2014). A group psychological intervention to enhance the coping and acculturation of international students. Advances in Mental Health, 12, 110–124. doi:10.1080/18374905.2014.11081889.

Stoliker, B. E., & Lafreniere, K. D. (2015). The influence of perceived stress, loneliness, and learning burnout on university students’ educational experience. College Student Journal, 49, 146–160.

Subrahmanyam, K., & Lin, G. (2007). Adolescents on the net: Internet use and well-being. Adolescence, 42, 659–677.

Tanner, J. L. (2011). Emerging adulthood. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 818–825). New York: Springer.

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 145–161. doi:10.1177/0022146510395592.

Thompson, R. A., Flood, M. F., & Goodvin, R. (2006). Social support and developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology (2nd ed., Vol. 3, Risk, disorder, and adaptation, pp. 1–37). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Uchino, B. N. (2004). Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Uchino, B. N. (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 236–255. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x.

Umberson, D., Crosnoe, R., & Reczek, C. (2010). Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 139–157. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011.

Vaughan, C. A., Foshee, V. A., & Ennett, S. T. (2010). Protective effects of maternal and peer support on depressive symptoms during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 261–272.

Weckwerth, A. C., & Flynn, D. M. (2006). Effect of sex on perceived support and burnout in university students. College Student Journal, 40, 237–249.

Weir, R. M., & Okun, M. A. (1989). Social support, positive college events, and college satisfaction: Evidence for boosting effects. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 19, 758–771. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1989.tb01257.x.

Wheaton, B. (1985). Models for the stress-buffering functions of coping resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 26, 352–364. doi:10.2307/2136658.

Wheaton, B., & Clark, P. (2003). Space meets time: Integrating temporal and contextual influences on mental health in early adulthood. American Sociological Review, 68, 680–706. doi:10.2307/1519758.

Zhang, B., Gao, Q., Fokkema, M., Alterman, V., & Liu, Q. (2015). Adolescent interpersonal relationships, social support and loneliness in high schools: Mediation effect and gender differences. Social Science Research, 53, 104–117. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.05.003.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jose Miguel Rodas for help with data collection.

Author Contributions

C.Y.S.L. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, performed the measurement and statistical analysis, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript; S.G. participated in the design, performed the measurement, interpreted the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, CY.S., Goldstein, S.E. Loneliness, Stress, and Social Support in Young Adulthood: Does the Source of Support Matter?. J Youth Adolescence 45, 568–580 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9