Abstract

Humans function based on secure social connections. Loneliness is an important factor that puts individuals at higher risks for poor well-being but explicating potential mediating and moderating factors that may link loneliness to poor well-being has been limited. Based on Hawkley and Cacioppo’s model of loneliness, this study tested whether loneliness is associated with a sense of meaning and purpose in life and explored possible mediating (self-compassion) and moderating (interpersonal mindfulness) effects of this association. A total of 410 university students completed measures of loneliness, self-compassion, meaning in life, interpersonal mindfulness, and trait mindfulness. A moderated mediation model result found that loneliness interferes with showing a healthy attitude toward oneself, linked to a low sense of meaning in life. This effect was exacerbated for those who are less interpersonally mindful. Findings suggest that loneliness stemming essentially from an interpersonal experience gets extended to creating unkind self-attitudes, which then is linked to meaning in life. Moreover, being judgmental and reactive during interpersonal interactions exacerbates this association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

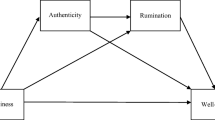

As humans have a fundamental need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), feeling isolated without meaningful social connections is a significant risk to human survival and thriving. Empirical research finds that feeling lonely is linked to poor well-being (see for a review, Erzen & Çikrikci, 2018), including low life satisfaction (Çivitci & Çivitci, 2009; Kong & You, 2013), low subjective well-being (VanderWeele et al., 2012), low happiness (Hombrados-Mendieta et al., 2013), and low meaning in life (Hicks & King, 2009). However, relatively less attention has been directed to identifying potential intermediary variables that may connect loneliness and meaning in life except for a few (e.g., Borawski, 2021). Hawkley and Cacioppo’s (2010) model of loneliness is a useful framework that can be applied to elucidate a potentially complex relationship between loneliness and meaning in life. This model posits that lonely individuals process information in a biased way by perceiving social cues as more threatening and by remembering more negative interchanges. Although this model suggests that social perception influences self-evaluation, to date, empirical research is limited in understanding how this negatively biased cognitive pattern (focusing on the “negatives” and amplifying the “negatives”) broods over to experiencing an unkind and critical self-view characterized by low self-compassion. This study seeks to address this gap in the literature by examining self-compassion as a mediating variable that connects loneliness and meaning in life.

On the other hand, if the negativity bias is what undergirds the relationship between loneliness to self-compassion, being mindful of one’s interpersonal patterns can help attenuate the association between loneliness and self-compassion. This nonjudgmental and non-reactive processing of internal and external experiences in social contexts is operationalized as interpersonal mindfulness (Medvedev et al., 2020; Pratscher et al., 2018), where high interpersonal mindfulness allows a clear and accurate interpersonal perception. Previous research widely documented the protective effects of mindfulness on the intrapersonal negative cognitive bias (Frewen et al., 2008; Kiken & Shook, 2012), but interpersonal mindfulness is a more appropriate construct when examining the perception of interpersonal cues that has not been examined. As such, this study incorporated interpersonal mindfulness to test whether interpersonal mindfulness moderates the relationship between loneliness and self-compassion.

1 Loneliness and Meaning in Life

Loneliness is a subjective feeling that a desired quantity or quality of social connections is not met, creating a perception of feeling socially isolated (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). It stems from a perceived discrepancy between desired social needs and availability in the environment (Hawkley & Capitanio, 2015). Individuals can feel lonely regardless of objective qualities such as the number or frequency of social connections, often operationalized as social connectedness or social isolation. Not surprisingly, loneliness is detrimental to well-being. For instance, loneliness is linked to depression (Cacioppo et al., 2006), suicidality (Schinka et al., 2012), happiness (Akdoğan & Çimşir, 2019), and subjective well-being (VanderWeele et al., 2012). Recently, King and Hicks (2021) argued that “the experience of meaning is often found and created through interdependence with others” (p. 571), highlighting that loneliness is detrimental to meaning in life as well.

Meaning in life is a subjective judgment of one’s life as meaningful, rising from daily life experiences used as informational sources (Heintzelman & King, 2014). Three facets compose meaning in life (Martela & Steger, 2016). These facets are coherence (or comprehension), purpose, and significance (or mattering) (George & Park, 2016; King et al., 2006). Coherence refers to the degree to which life, events, and experiences make sense. When there is a sense of coherence, individuals experience that things in life are “clear and fit together well.” (George & Park, 2016, p. 208). Therefore, predictable and consistent patterns in the environment facilitate experiencing coherence (Heintzelman & King, 2014). Purpose refers to having a sense that life is directed towards important goals. Striving for and achieving importantly valued life goals give a sense that individuals are engaged with their lives and are directed to the desired path. To experience purpose in life, therefore, involves self-regulation to work towards these goals (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009). Significance (mattering) refers to sensing that one’s life is fundamentally inherently of value. It is a sense that their existence matters. To not be forgotten (Ray et al., 2019) is a robust factor that facilitates experiencing significance. These three facets of meaning in life work interactively, with documented facilitators and barriers to experiencing meaning in life (King & Hicks, 2021).

Negative associations between loneliness and meaning in life have been reported in correlational, experimental, and neuroscience studies. For example, loneliness and meaning in life showed a negative association, especially among those who were induced of neutral emotions (Hicks &, King, 2009). Experimentally manipulating social exclusion also decreased meaning in life (Stillman et al., 2009). Distinct neural activation patterns were shown for loneliness and meaning in life, showing an inverse association and interdependence (Mwilambwe-Tshilobo et al., 2019). In sum, evidence converges to support that loneliness and meaning in life are negatively associated.

2 Theoretical Basis to Linking Loneliness and Meaning in Life

Although several studies reported that loneliness and meaning in life are associated, they failed to find how these two might be linked. Hawkley and Cacioppo’s (2010) model of loneliness helps explain why loneliness and meaning in life are negatively associated. According to the model, lonely individuals hold a cognitive bias characterized by perceiving social cues in a threatening way and remembering more negative social information (Spithoven et al., 2017). This cognitive bias may create lack of coherence, purpose, and significance, and thus an overall low meaning in life. Specifically, predictable and consistent patterns of the environment facilitate experiencing coherence (Heintzelman & King, 2014). However, if this predictable and consistent pattern is of negative valence (invoking feelings of loneliness), it may function conversely against meaning in life. In other words, social cues are biasedly negatively interpreted for those high in loneliness, which further propels social isolation (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Loneliness may also interfere with experiencing a sense of purpose. Loneliness provokes feelings of hopelessness (Chang et al., 2010), which may deter having the enthusiasm and hope to accomplish important life goals. Lastly, loneliness may interfere with perceiving that life matters and is of significance, as one of the core human needs of connectedness is thwarted (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). In sum, this cognitive bias may underlie the negative association between loneliness and meaning in life.

3 Loneliness and Self-Compassion

Although it is widely accepted that there is a cognitive bias in interpreting and memorizing social cues from others, relatively less known is whether a similar cognitive bias may be at play for self-evaluations. Some research reported that lonely individuals tended to evaluate themselves more negatively (Spithoven et al., 2017), and that lonely individuals are biased to evaluate their social performance in a more negative light (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Lonely individuals also showed low self-rating on positive characteristics (Tsai & Reis, 2009). These results highlight that cognitive bias about the social world gets extended to negative self-evaluation. Although the negative bias prevalent in social perception extends to self-perception characterized by criticism and judgment, what has not been explored is whether this negative bias also creates an unkind and uncompassionate self-attitude. Showing self-criticism and self-judgment may not necessarily translate to unkindness and less compassion for oneself, and hence need to be separately examined.

An unkind and uncompassionate self-attitude can be best characterized by low self-compassion. Self-compassion refers to relating to oneself with kindness and compassion in the face of adversity and difficulties (Neff, 2003). When acknowledging personal inadequacies or painful life situations, self-compassion extends an open awareness and kindness to the self, noticing that it is a common human experience to struggle (Neff, 2003). Low self-compassion, therefore, is lacking awareness about one’s struggles and extending an unkind and isolating attitude toward oneself. Low self-compassion is related to worse relationship functioning (Neff & Beretvas, 2013) and poor perspective-taking.

Whereas self-compassion functions as an adaptive emotion regulation strategy by preventing appraising negative events to have negative implications for oneself (Finlay-Jones, 2017), lonely individuals are impaired with an accurate appraisal capacity, likely showing low self-compassion. A few studies reported an inverse association between loneliness and self-compassion (Akin, 2010) and social disconnection and self-compassion (Neff & McGehee, 2010), suggesting that further examination of the relationship between loneliness and self-compassion may be helpful and necessary to elucidate how social perception gets extended to self-responding.

4 Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life

Self-compassion is associated with various well-being indicators including negative/positive affect, life satisfaction, happiness, and psychological well-being (see for a review, Barnard & Curry, 2011). This is because self-compassion allows one to respond to personal failures, mistakes, and challenges with a more balanced perspective and equanimity (Leary et al., 2007). In other words, self-compassion provides feelings of safety and security (Neff, 2011), serving as a basis for better well-being.

Experiencing meaning in life is a relatively less examined well-being indicator with self-compassion, but conceptually a relevant one that may benefit from close examination. For instance, accepting one’s failures and bringing kindness may help integrate both positive and negative experiences as a human experience. This can help individuals feel that their lives make sense. Greater self-compassion may also provide a sense of purpose to continue to live in a value-aligned direction despite failures or setbacks. Lastly, knowing that individual failures are not due to personal inadequacy and that all humans experience pain may help understand that life is important and significant. In fact, several studies found that self-compassion positively predicted meaning in life across various samples (Bercovich et al., 2020; Phillips & Ferguson, 2013).

Unfortunately, no study sought to connect compartmentalized research findings that independently examined the relations between loneliness and meaning in life, loneliness and self-compassion, and self-compassion and meaning in life. As such, this study attempted to connect previous research by positing self-compassion as a mediating factor that links the association between loneliness and meaning in life.

5 Interpersonal Mindfulness as a Moderator

If perception about the social world informs self-attitude, one of the ways that can mitigate this link is by showing an accurate perception of the self in social contexts. This may be possible when individuals are mindful by paying undivided and non-judgmental attention to interpersonal cues and interactions, rather than having cognitive bias as a default mode of information processing. Thus, interpersonal mindfulness can moderate the association between loneliness and self-compassion.

Previous studies reported the protective function of mindfulness in interpersonal domains. For instance, high mindfulness in parenting is considered to have positive effects on the parent-child relationship by interfering with the automatic processing of social information in an unregulated and impulsive way, reducing the likelihood of acting upon those impulses (Duncan et al., 2009). Similarly, high mindfulness in romantic relationships predicted greater relationship satisfaction (Kozlowski, 2013). Although mindfulness in social domains (parenting, romantic partner) has been widely examined, these studies either used trait mindfulness as a proxy to mindfulness enacted in interpersonal domains or used a specific measure that only focused on one role (e.g., Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting by Duncan, 2007).

Mindfulness that particularly applies to and manifests in the interpersonal domain is operationalized as interpersonal mindfulness (Pratscher et al., 2019). Whereas trait mindfulness refers to being mindful in all aspects of life events and experiences, interpersonal mindfulness is narrower in its focus. Interpersonal mindfulness is strongly correlated with trait mindfulness (r = 0.70), but a series of studies found that it uniquely reflects the manifestation and application of mindfulness in the context of interpersonal actions and is a better predictor of interpersonal functioning compared to trait mindfulness (Pratscher et al., 2018). High interpersonal mindfulness indicates showing receptive awareness of moment-by-moment processes that are part of interpersonal actions. This receptive awareness can be directed to both external stimuli and events as well as internal thoughts, emotions, and sensations.

In sum, endorsing high interpersonal mindfulness is likely to allow individuals to not distort social cues and notice their reactions with nonjudgment, all of which will attenuate the relationship between loneliness and self-compassion. Conversely, endorsing low interpersonal mindfulness will only exacerbate the negative association between loneliness and self-compassion. Thus, interpersonal mindfulness may moderate the association between loneliness and self-compassion, linked to meaning in life.

6 Present Study

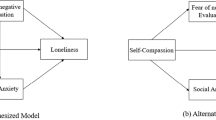

This study examined the association between loneliness and meaning in life, focusing on the mediating role of self-compassion and a moderating role of interpersonal mindfulness of this indirect effect (Fig. 1). It was expected that there will be a negative association between loneliness and meaning in life (Hypothesis 1) and that this negative association is mediated by self-compassion (Hypothesis 2). As for the moderation effect, it was hypothesized that the negative association between loneliness and self-compassion will be stronger for those who are low on interpersonal mindfulness, thereby combinedly predicting meaning in life (Hypothesis 3). When individuals are lonely, this makes it difficult to be kind to themselves, and being less interpersonanse of meaning in life. Slly mindful and tending to negatively interpret interpersonal cues could only exacerbate the effect that loneliness has on self-compassion, which then ultimately influences meaning in life.

7 Method

7.1 Participants and Procedure

Data were gathered from a sample of undergraduate students at a Northeastern public university in the USA (N = 410) after the university’s Institutional Review Board approval. Participants were recruited from various psychology classes (e.g., introductory psychology, abnormal psychology, statistical analysis in psychology) in exchange for course credit. The data for this study comes from a larger study that was advertised as an online research survey on personality and health. Students who are 18 years or older and have reliable access to a computer with an internet connection were invited to participate. Participation was voluntary and informed consent was gathered from participants. Participation was limited to one per student, regardless of the number of courses they were enrolled in. A total of 452 reports were initially gathered, but 42 were excluded (e.g., incompletions, repeated access by an identical participant), leaving 410 valid data. The mean age was 21.16 (SD = 5.21, Median age = 19.00, ranging from 18 to 60 [over 90% were 25 or under]). Approximately 55% of participants identified as White, 22% Hispanic, 11% African American, 5% multiracial, 4% Asian American, and 4% as “Other.” Approximately 82% were women, 17% were men, and less than 1% were transgender.

8 Measures

Meaning in Life. The Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale (MEMS; George & Park, 2016) was used to assess experiences of meaning in life. The MEMS is a 15-item measure composed of three subscales (coherence, purpose, significance). Participants responded on a 7-point scale (1 = Very Strongly Disagree, 7 = Very Strongly Agree) and higher scores indicated a greater sense of meaning in life. Sample items include, “I can make sense of the things that happen in my life (coherence),” “I have certain life goals that compel me to keep going (purpose),” and “I am certain that my life is of importance (significance).” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90 (coherence), 0.89 (purpose), and 0.84 (significance) respectively in a college sample, and validity was also evidenced (George & Park, 2016).

Loneliness. The UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3 (ULS-3; Russell, 1996) was used to assess how often one feels lonely, the subjective perception of social isolation. The ULS-3 is composed of 20 items with sample items such as “How often do you feel alone?” and “How often do you feel left out?” Participants responded on a 4-point scale (1 = Never, 4 = Often) and higher scores indicated greater loneliness. Cronbach’s alpha has been consistently high across studies using this measure (Vassar & Crosby, 2008), and convergent and discriminant validity were supported (Russell, 1996).

Self-Compassion. The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003) was used to assess compassionately relating to the self. The SCS (Neff, 2003) is a 26-item measure designed to assess overall self-compassion, composed of six facets. Three self-compassion facets (Self-Kindness, Common Humanity, and Mindfulness) that mainly reflect compassionate self-responding (CS) were used in this study, given the mixed findings that challenge the validity of utilizing the total score of all six facets (e.g., Brenner et al., 2017; 2018). Specifically, Neff (2019, 2022) argues that the SCS subscales represent opposite ends of bipolar continuums (CS to uncompassionate self-responding [UCS]) and that a total score of the SCS can be used to represent overall self-compassion. However, a sizable research volume supports that not only are CS and UCS conceptually distinct, but they also differentially relate to outcome variables, supporting against using the total SCS score (see for a comprehensive review and argument, Muris & Otgaar, 2022). Given the ongoing debate and our interest in capturing self-compassion (and not self-criticism or self-harshness), we opted to only use three CS facets. Participants responded to a 5-point scale (1 = Almost Never, 5 = Almost Always) and higher scores indicated greater self-compassion. Sample items include, “I try to be loving towards myself when I’m feeling emotional pain (self-kindness),” “I try to see my failings as part of the human condition (common humanity),” and “When something upsets me I try to keep my emotions in balance (mindfulness).” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91 and discriminant and convergent validity were also demonstrated (Brenner et al., 2018).

Interpersonal Mindfulness. The Interpersonal Mindfulness Scale (IMS; Pratscher et al., 2019) was used to assess mindfulness during interpersonal interactions. The IMS is composed of 27 items with four subscales: presence, awareness of self and others, nonjudgmental acceptance, and nonreactivity. Participants responded to a 5-point scale (1 = Almost Never, 5 = Almost Always) and higher scores indicated greater interpersonal mindfulness. Sample items include “I notice how my mood affects how I act towards others,” and “When I am with another person, I try to accept how they are behaving without wanting them to behave different.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 and validity was also supported (Pratscher et al., 2019).

Trait Mindfulness. The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006) was used to assess trait mindfulness that was entered as a covariate to be controlled for, given the high correlations with self-compassion and interpersonal mindfulness. The FFMQ is composed of 39 items with five subscales: observing, describing, acting with awareness, nonjudgment, and nonreactivity to inner experience. Sample items include “I perceive my feelings and emotions without having to react to them,” and “When I have distressing thoughts or images, I just notice them and let them go.” Participants respond on a 5-point scale (1 = Never or Very Rarely True, 5 = Very Often or Always True) and higher scores indicated greater trait mindfulness. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.75 to 0.91 for the five-facet scales (Baer et al., 2006). The FFMQ also showed good construct validity (Baer et al., 2006) and discriminate validity (de Bruin et al., 2012).

9 Data Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 24.0. Several preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure the quality and reliability of the data. There was no missing data with a 100% response rate. A review of normal P-P plots of each predicted value of the predictor and residual value of dependent variable pairs found linear relationships, supporting the linearity assumption. Skewness and kurtosis values were all less than 0.5 suggesting the normal distribution of variables. We used robust standard error (HC4) available in the PROCESS macro and thus potential heteroscedasticity was not a concern. In terms of descriptive statistics, internal consistency and correlation among variables were examined and are presented in Table 1. For the main analysis, using bias-corrected bootstrapping, a moderated mediation model (PROCESS Model 7) with 10,000 bootstrapped samples was run (Hayes, 2017). Trait mindfulness was included as a covariate to be controlled for, given its high correlation with interpersonal mindfulness.

10 Results

As can be seen in Table 2, results found that loneliness was negatively associated with self-compassion (b = − 0.17, p < 0.001). Self-compassion was positively associated with meaning in life (b = 0.52, p < 0.001) and loneliness was negatively associated with meaning in life (b = − 0.35, p < 0.001). This suggests a significant mediation effect of self-compassion in the association between loneliness and meaning in life. The interaction of loneliness and interpersonal mindfulness was significantly related to self-compassion (b = 0.01, p < 0.05) suggesting that interpersonal mindfulness moderated the association between loneliness and self-compassion (Fig. 2). Lastly, results showed that the moderated mediation effect was significant (Index = 0.0035, SE = 0.002, 95% CI: [0.0003, 0.0072]). As such, we probed the conditional indirect effect of loneliness on meaning in life. As can be seen in Table 3, the indirect effect was significant at low levels (16th percentile, -1SD) of interpersonal mindfulness (b = − 0.13, SE = 0.04, 95% CI: [− 0.22, − 0.05]), and medium levels (50th percentile) of interpersonal mindfulness (b = − 0.09, SE = 0.03, 95% CI: [− 0.15, − 0.03]), but not at high levels (84th percentile, +1SD) of interpersonal mindfulness (b = − 0.04, SE = 0.03, 95% CI: [− 0.11, 0.02]). To examine at what level of interpersonal mindfulness does the effect of loneliness on self-compassion transitions from significance to nonsignificance, we applied the Johnson-Neyman method (Johnson & Fay, 1950). Loneliness was significantly negatively related to self-compassion at values below the 83.66th percentile of interpersonal mindfulness but became nonsignificant at values above this percentile of interpersonal mindfulness. The alternative reverse model (self-compassion [IV], loneliness [mediator], interpersonal mindfulness [moderator], meaning in life [DV]) was not supported (95% CI: [-0.004, 0.001]).

11 Discussion

The goal of this study was to advance our understanding of how loneliness and meaning in life are associated, particularly focusing on identifying potential roles of self-compassion and interpersonal mindfulness. Results found support for a direct association between loneliness and meaning in life (Hypothesis 1 supported) and self-compassion was a significant mediator in this association (Hypothesis 2 supported). Lastly, low interpersonal mindfulness moderated the indirect effect of self-compassion in the association between loneliness and meaning in life, supporting the moderating effect of interpersonal mindfulness (Hypothesis 3 supported).

First, regarding the direct effect of loneliness on meaning in life, results confirmed that not having a secure relationship that fulfills relational needs is negatively associated with experiencing meaning in life. Loneliness is negatively associated with sensing purpose and significance of existence in the world. When loneliness is prevalent, it is also difficult to comprehend life’s meaning due to constant cognitive biases and distortions that undergird attentional and memory processes. This finding integrates well into the existing literature showing a negative association between loneliness and well-being (Goodfellow et al., 2022; Matthews et al., 2019). It also complements loneliness literature that has consistently found how feeling isolated with limited meaningful social relationships is negatively associated with all aspects of human functioning, ranging from poor physical health such as mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015) to psychological distress symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation (Beutel et al., 2017). Furthermore, this finding addresses previous research that called for clarifications on the nature and qualities of young adult loneliness, against abundant attention on elderly loneliness research (Goodfellow et al., 2022; Qualter et al., 2015). Our finding indicated that loneliness in young adults is negatively associated with feeling a sense of meaning in life, similar to other age groups.

Our finding also sheds light on one way in which loneliness is associated with meaning in life. Specifically, loneliness was negatively associated with self-compassion, and self-compassion was positively associated with meaning in life. How might loneliness, an essentially interpersonal perception, be related to an attitude about oneself? Hawkley and Cacioppo (2010) highlight that biased cognitive processing undergirds the way that lonely individuals process external stimuli and events. This cognitive bias is extended to self-evaluations that are inwardly directed, and isolating interpersonal experiences create non-soothing attitudes about the self. The mediating effect of self-compassion can be understood in the context of divergent activation of affect regulation systems (Gilbert, 2005). When individuals high in loneliness consider the social world to be threatening, this activates a threat-based affect regulation system, which hinders access to a social safeness/soothing system (Gilbert, 2005). It is difficult to respond with kindness stemming from the activation of a social safeness/soothing system when social cues are perceived as threatening while cognitions and behaviors are geared toward self-defense (e.g., aggression, avoidance). Likewise, it is difficult to be self-compassionate when defending oneself in anticipation of a potential threat (threat can be both externally instigated by others or internally from negative self-talks) becomes the default mode of functioning. Loneliness makes access to the social safeness/soothing system increasingly distant, leaving minimal space to direct self-kindness and compassion. This study contributes to the literature by expanding our understanding to include the dynamics between the threat-based affect regulation system and the social safeness/soothing affect regulation system (Gilbert, 2005).

The moderating effect of interpersonal mindfulness of the indirect effect suggests that the negative association between loneliness and self-compassion was significant when interpersonal mindfulness was low. This indicates that not being attentive and aware of internal cognitions, emotions, and sensations regarding interpersonal cues and actions exacerbates the negative association between loneliness and self-compassion. Loneliness often triggers negative emotions such as feeling unwanted and unloved (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982) and lack of interpersonal mindfulness intensifies the difficult and negative emotions that get precipitated by loneliness, linked to low self-compassion.

When interpersonal mindfulness was high, the association between loneliness and meaning in life was not mediated by self-compassion. This suggests that low interpersonal mindfulness worsens the negative association between loneliness on self-compassion, but high interpersonal mindfulness does not necessarily weaken the association between loneliness, self-compassion, and meaning in life. One explanation might be that high interpersonal mindfulness already creates an array of positive effects that may nullify the effect of loneliness.

There is a well-established link between low mindfulness and greater psychological distress, such as depression, anxiety, and negative affect (Brown & Ryan, 2003), suggesting that high mindfulness may play a protective role. Many mindfulness-based interventions also witness positive effects on psychological health (Keng et al., 2011), supporting that high mindfulness is helpful. Yet, it appears that the protective role of mindfulness is still an empirical question to be tested, at least in the context of loneliness research. A recent review by Teoh et al. (2021) found that loneliness levels significantly reduced after participating in 8-week mindfulness-based intervention programs, but the quality of aggregated evidence was low, suggesting that the result should be interpreted with caution as there is substantial uncertainty about the result. Perhaps with loneliness, increasing interpersonal mindfulness through interventions, rather than general trait mindfulness, may provide an effect that may be distinguishable, but limited research on interpersonal mindfulness deter us from making any conclusive interpretations. Given the nascent nature of the interpersonal mindfulness construct, more research should be conducted to garner converging evidence on the effects of interpersonal mindfulness.

12 Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to this study that may inform future research. First, given that we utilized cross-sectional data, causality cannot be inferred. Although the hypothesized moderated mediation model was further supported by ruling out an alternative reverse model and was underpinned by a theoretical framework, utilizing experimental design or longitudinal design can establish the causality of the associations. Future studies could utilize a social isolation experimental design (Lambert et al., 2013) or a longitudinal design to examine the causal relationship of loneliness predicting meaning in life through self-compassion, and more broadly with self-attitudes. Second, this study was conducted with undergraduate students and thus findings cannot be generalized to other age groups. Some previous findings report age effects on loneliness and mindfulness (Shook et al., 2017; Yang & Victor, 2011). Future studies could test whether the same tested model and results hold for non-college-aged samples. Related, given that approximately 82% of this study’s sample was women, future studies would benefit from having a more balanced gender ratio to examine the potential role of gender. Lastly, including objective measurements of social relationships could bolster the current findings. Although there is a clear distinction between subjective perception of loneliness and objective assessment of social relationships, young adults may be particularly vigilant to expand their social network size. Future studies can examine the independent and synergistic effects of loneliness and social networks with young adults. Despite these limitations, this study adds to the literature by explaining the role of self-compassion and interpersonal mindfulness in the association between loneliness and meaning in life.

References

Akdoğan, R., & Çimşir, E. (2019). Linking inferiority feelings to subjective happiness: Self-concealment and loneliness as serial mediators. Personality and Individual Differences, 149, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.028.

Akin, A. (2010). Self-compassion and loneliness. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 2(3), 702–718.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504.

Barnard, L. K., & Curry, J. F. (2011). Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of General Psychology, 15(4), 289–303.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Bercovich, A., Goldzweig, G., Igra, L., Lavi-Rotenberg, A., Gumley, A., & Hasson-Ohayon, I. (2020). The interactive effect of metacognition and self-compassion on predicting meaning in life among individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 43(4), 290–298.

Beutel, M. E., Klein, E. M., Brähler, E., Reiner, I., Jünger, C., Michal, M., Wiltink, J., Wild, P. S., Münzel, T., Lackner, K. J., & Tibubos, A. N. (2017). Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC psychiatry, 17(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x

Borawski, D. (2021). Authenticity and rumination mediate the relationship between loneliness and well-being. Current Psychology, 40(9), 4663–4672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00412-9

Brenner, R. E., Heath, P. J., Vogel, D. L., & Credé, M. (2017). Two is more valid than one: Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(6), 696–707. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000211.

Brenner, R. E., Vogel, D. L., Lannin, D. G., Engel, K. E., Seidman, A. J., & Heath, P. J. (2018). Do self-compassion and self-coldness distinctly relate to distress and well-being? A theoretical model of self-relating. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(3), 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000257.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140.

Chang, E. C., Sanna, L. J., Hirsch, J. K., & Jeglic, E. L. (2010). Loneliness and negative life events as predictors of hopelessness and suicidal behaviors in Hispanics: Evidence for a diathesis-stress model. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(12), 1242–1253. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20721.

de Bruin, E. I., Topper, M., Muskens, J. G. A. M., Bögels, S. M., & Kamphuis, J. H. (2012). Psychometric properties of the five facets mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ) in a meditating and a non-meditating sample. Assessment, 19(2), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191112446654.

Duncan, L. G. (2007). Assessment of mindful parenting among parents of early adolescents: Development and validation of the Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting scale. Unpublished dissertation.

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 255–270.

Erzen, E., & Çikrikci, Ö. (2018). The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 64(5), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764018776349.

Finlay-Jones, A. L. (2017). The relevance of self‐compassion as an intervention target in mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review based on an emotion regulation framework. Clinical Psychologist, 21(2), 90–103.

Frewen, P. A., Evans, E. M., Maraj, N., Dozois, D. J., & Partridge, K. (2008). Letting go: Mindfulness and negative automatic thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(6), 758–774.

George, L. S., & Park, C. L. (2016). Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: Toward integration and new research questions. Review of General Psychology, 20(3), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000077.

Gilbert, P. (2005). Social mentalities: A biopsychosocial and evolutionary reflection on social relationships. In M. W. Baldwin (Ed.), Interpersonal cognition (pp. 299–335). New York: Guilford.

Goodfellow, C., Hardoon, D., Inchley, J., Leyland, A. H., Qualter, P., Simpson, S. A., & Long, E. (2022). Loneliness and personal well-being in young people: Moderating effects of individual, interpersonal, and community factors. Journal of Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12046.

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8.

Hawkley, L. C., & Capitanio, J. P. (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: A lifespan approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1669), 20140114. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0114.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Heintzelman, S. J., & King, L. A. (2014). Life is pretty meaningful. American Psychologist, 69(6), 561–574. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035049.

Hicks, J. A., & King, L. A. (2009). Positive mood and social relatedness as information about meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 471–482.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237.

Hombrados-Mendieta, I., García-Martín, M. A., & Gómez-Jacinto, L. (2013). The relationship between social support, loneliness, and subjective well-being in a spanish sample from a multidimensional perspective. Social indicators research, 114(3), 1013–1034.

Çivitci, N., & Çivitci, A. (2009). Self-esteem as mediator and moderator of the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 954–958.

Johnson, P. O., & Fay, L. C. (1950). The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika, 15(4), 349–367.

Keng, S. L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1041–1056.

Kiken, L. G., & Shook, N. J. (2012). Mindfulness and emotional distress: The role of negatively biased cognition. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 329–333.

King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2021). The science of meaning in life. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 561–584. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-072420-122921.

King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L., & Del Gaiso, A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 179–196.

Kong, F., & You, X. (2013). Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Social Indicators Research, 110(1), 271–279.

Kozlowski, A. (2013). Mindful mating: Exploring the connection between mindfulness and relationship satisfaction. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 28(1–2), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2012.748889.

Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213499186.

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Allen, B., A., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887–904.

Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623.

Matthews, T., Danese, A., Caspi, A., Fisher, H., Goldman-Mellor, S., Kepa, A., & Arseneault, L. (2019). Lonely young adults in modern Britain: Findings from an epidemiological cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 49(2), 268–277.

McKnight, P. E., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Review of general Psychology, 13(3), 242–251.

Medvedev, O. N., Pratscher, S. D., & Bettencourt, A. (2020). Psychometric evaluation of the interpersonal mindfulness scale using rasch analysis. Mindfulness, 11(8), 2007–2015.

Muris, P., & Otgaar, H. (2022). Deconstructing self-compassion: How the continued use of the total score of the Self-Compassion Scale hinders studying a protective construct within the context of psychopathology and stress. Mindfulness, 13, 1403–1409.

Mwilambwe-Tshilobo, L., Ge, T., Chong, M., Ferguson, M. A., Misic, B., Burrow, A. L., & Spreng, R. N. (2019). Loneliness and meaning in life are reflected in the intrinsic network architecture of the brain. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 14(4), 423–433.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self‐esteem, and well‐being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 1–12.

Neff, K. D. (2019). Setting the record straight about the Self-Compassion Scale. Mindfulness, 10(1), 200–202.

Neff, K. D. (2022). The differential effects fallacy in the study of self-compassion: Misunderstanding the nature of bipolar continuums. Mindfulness, 13(3), 572–576.

Neff, K. D., & Beretvas, S. N. (2013). The role of self-compassion in romantic relationships. Self and Identity, 12(1), 78–98.

Neff, K. D., & McGehee, P. (2010). Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and Identity, 9(3), 225–240.

Paloutzian, R. F., & Ellison, C. W. (1982). Loneliness, spiritual wellbeing and quality of life. In L. A. Peplau, & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research, and therapy (pp. 224–237). New York: Wiley.

Phillips, W. J., & Ferguson, S. J. (2013). Self-compassion: A resource for positive aging. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(4), 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs091.

Pratscher, S. D., Rose, A. J., Markovitz, L., & Bettencourt, A. (2018). Interpersonal mindfulness: Investigating mindfulness in interpersonal interactions, co-rumination, and friendship quality. Mindfulness, 9(4), 1206–1215.

Pratscher, S. D., Wood, P. K., King, L. A., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2019). Interpersonal mindfulness: Scale development and initial construct validation. Mindfulness, 10(6), 1044–1061.

Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., & Verhagen, M. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 250–264.

Ray, D. G., Gomillion, S., Pintea, A. I., & Hamlin, I. (2019). On being forgotten: Memory and forgetting serve as signals of interpersonal importance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(2), 259–276.

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2.

Schinka, K. C., VanDulmen, M. H., Bossarte, R., & Swahn, M. (2012). Association between loneliness and suicidality during middle childhood and adolescence: Longitudinal effects and the role of demographic characteristics. Journal of Psychology, 146(1–2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.584084.

Shook, N. J., Ford, C., Strough, J., Delaney, R., & Barker, D. (2017). In the moment and feeling good: Age differences in mindfulness and positive affect. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 3(4), 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000139.

Spithoven, A. W., Bijttebier, P., & Goossens, L. (2017). It is all in their mind: A review on information processing bias in lonely individuals. Clinical Psychology Review, 58, 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.003.

Stillman, T. F., Baumeister, R. F., Lambert, N. M., Crescioni, A. W., DeWall, C. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). Alone and without purpose: Life loses meaning following social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.007.

Teoh, S. L., Letchumanan, V., & Lee, L. H. (2021). Can mindfulness help to alleviate loneliness? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 633319.

Tsai, F. F., & Reis, H. T. (2009). Perceptions by and of lonely people in social networks. Personal Relationships, 16(2), 221–238.

VanderWeele, T. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). On the reciprocal association between loneliness and subjective well-being. American Journal of Epidemiology, 176(9), 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws173.

Vassar, M., & Crosby, J. W. (2008). A reliability generalization study of coefficient alpha for the UCLA loneliness scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90(6), 601–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802388624.

Yang, K., & Victor, C. (2011). Age and loneliness in 25 european nations. Ageing & Society, 31(8), 1368–1388.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Indiana University Institutional Review Board approved this study. Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained by participants clicking “agree” button at the end of the informed consent document in an online survey.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Suh, H., Lee, J. Linking Loneliness and Meaning in Life: Roles of Self-Compassion and Interpersonal Mindfulness. Int J Appl Posit Psychol 8, 365–381 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00094-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00094-6