Abstract

Purpose

Employers play an important role in facilitating sustainable return to work (RTW) by workers with disabilities. The aim of this qualitative study was to explore how employers who were successful in retaining workers with disabilities at work fulfilled their supportive role, and which facilitators were essential to support these workers throughout the RTW process.

Methods

We conducted a semi-structured interview study among 27 employers who had experience in retaining workers with disabilities within their organization. We explored the different phases of RTW, from the onset of sick leave until the period, after 2-years of sick-leave, and when they can apply for disability benefit. We analyzed data by means of thematic analysis.

Results

We identified three types of employer support: (1) instrumental (offering work accommodations), (2) emotional (encouragement, empathy, understanding) and (3) informational (providing information, setting boundaries). We identified three facilitators of employer support (at organizational and supervisor levels): (1) good collaboration, including (in)formal contact and (in)formal networks; (2) employer characteristics, including supportive organizational culture and leadership skills; and (3) worker characteristics, including flexibility and self-control.

Conclusions

Employers described three different possible types of support for the worker with disabilities: instrumental, emotional, and informational. The type and intensity of employer support varies during the different phases, which is a finding that should be further investigated. Good collaboration and flexibility of both employer and worker were reported as facilitators of optimal supervisor/worker interaction during the RTW process, which may show that sick-listed workers and their supervisors have a joint responsibility for the RTW process. More insight is needed on how this supervisor/worker interaction develops during the RTW process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over recent decades several OECD countries have reformed their disability programs to foster labor market integration of people confronted with challenges to staying or re-entering the workforce due to illness or disabilities [1]. These reforms focus primarily on reintegrating workers with disabilities into employment, recognizing that many have only partially reduced work capacity and can therefore continue working if adequately supported by their employer [1,2,3]. In the Netherlands, the Dutch Gatekeeper Improvement Act describes obligatory procedures for workers with physical or mental health disabilities and employers to follow during the 2 years after sick leave. Workers on long-term sick leave (> 2 years) can apply for disability benefits and will be assessed by an insurance physician of the Social Security Institute. In this study, we focus on workers assessed as having residual work capacities receiving partial disability benefits. Since these reforms the employment rates of people with disabilities have gradually increased [1, 4].This may suggest that employment outcomes of people with disabilities are affected not only by their health conditions but also by their work environment [5].

There is growing understanding in research and practice that employers play an important supportive role in preventing early labor market exit by workers with disabilities. This support can be offered at organizational and individual level within the organisation [6]. Both the employers’ disability management policies and practices and the social interaction between the individual supervisor and the worker may influence job retention [7]. An employer can support workers by offering workplace accommodations that facilitate quicker return to work [8]. In addition, offering emotional support can create a good relationship between the supervisor and worker during the RTW-process by sustaining cohesion and communication and by responding to the needs of the worker [9]. A study on the perspective of the workers showed that workers perceive a lack of emotional support as a barrier to the RTW outcomes [10].

Besides considering the different levels of employer support (organizational and supervisory), RTW should also be considered as a process consisting of different RTW phases, especially when focusing on the role of employer support among workers who were sick listed for a long-time [11]. Employer support can be conceptualized as both the employers’ disability management policies and practices and the social interaction between employers and employees which may influence work participation of workers with disabilities. Employers’ involvement during each of the RTW phases of sick-leave, RTW and post-RTW, can facilitate workers’ RTW outcomes [9], but the type and intensity of support in different phases may vary [12]. During sick-leave, the supervisor and the worker can communicate frequently about the need for work accommodations and ways to accelerate RTW [13]. During RTW, employers can implement work accommodations that help the worker to continue working [14]. It is important that employers coordinate specific actions aimed at facilitating sustainable RTW [15]. During the post-RTW phase, communication with the worker is vital in the process towards sustainable employability [16].

Despite ample evidence of the importance of employer support in the RTW process of workers with disabilities, little is understood about how employers deal in practice with this role in the RTW process, and which facilitators of their support are most important for sustainable RTW. While previous qualitative studies have indicated that employer support is relevant to address the diverse needs of these workers, the majority of studies have focused on this role of the employer in RTW following short-term sick leave, but not following long-term sick leave [9, 17]. In addition, most interview studies explored employer support only from the perspective of the workers [17,18,19], instead of focusing on the perspective of employers. Although a few studies did include the employers’ perspective on the RTW process [20, 21], these studies focused only on the long-term sickness absence phase, and did not include all phases of the RTW process. Other studies of employer perspectives mainly focused on barriers and facilitators of workers who were unable to continue working [19], instead of focusing on cases where workers were able to stay in the labor market. Most of these studies focused on the challenges employers perceive, but not on the offered support that is relevant for work participation. We can learn from employers who succeeded in facilitating RTW and continued employment for workers with disabilities, to see which elements are relevant. The innovation of this study is that we focus on the perspective of the employer on their supportive role during the long-term RTW process.

Against this background, the aim of this qualitative study was to explore how employers who succeeded in retaining workers with physical or mental disabilities at work fulfilled their supportive role, the kind of support they offered, and which facilitators of employer support are essential to accommodate workers with disabilities throughout the RTW process.

Methods

Design

We conducted individual semi-structured interviews with employers’ representatives (i.e., supervisors, HR managers, and case managers).

Ethical Considerations

We received ethical approval from the Medical Ethical Review Board (METc) of the University Medical Center Groningen. Prior to beginning semi-structured interviews with employers, we obtained their written informed consent. All employers approved audiotaping of the interviews, and their use for scientific research after anonymization.

Institutional Setting

In the Netherlands, the employer is the most important stakeholder in the RTW process, one with a substantial financial and practical responsibility [22]. According to the Dutch Gatekeeper Improvement Act, in cases of sickness absence, both the employer and worker are responsible for the recovery and return to work of the (long-term) sick-listed worker [23]. This legislation describes obligatory procedures for workers and employers to follow. After 6–8 weeks of sick leave, the worker and employer need to develop a RTW plan [24]. After 2 years of sick leave, insurance physicians working at the Social Security Institute for Worker Benefit Schemes (UWV) assess workers for disability benefits [25]. Workers assessed as having residual work capacities receive partial disability benefits [26]. Employers may keep these workers in the workplace, but are also allowed to terminate their contracts. Dutch regulations, with a clear focus on activation of workers with disabilities, guarantee employer involvement in RTW [27]. This makes the Dutch context interesting for research into employers’ perspectives on sustainable RTW by workers with disabilities.

Selection of Employers

We used purposive sampling to recruit employers from organizations in different sectors and of different sizes (small, medium or large). We selected employers who, since 2017, had experience in retaining one or more workers with disabilities within their own organization. Disabilities was defined as having physical or mental health problems affecting work capacities. Workers with disabilities were defined as workers who had been assessed by the insurance physicians, had residual work capacities, and were receiving partial disability benefits due to long-term mental or physical disabilities. We chose 2017 because the RTW trajectory lasts 2 years in the Netherlands. In the first round of selection, the Social Security Institute for Employee Benefit Schemes (UWV) sent information letters to 200 employers. These letters included information on the aim of the study, the interview procedure, the inclusion criteria, and how to sign up (registration form, or an e-mail or phone call to the researcher). After registration, employer representatives were screened for study eligibility by answering several questions, using Qualtrics, mail, or telephone. Inclusion criteria were: (1) understanding of the Dutch language, and (2) having a job function within an organization experienced in successfully supporting long-term sick-listed workers during all identified RTW phases. Employer representatives could be HR managers, case managers, or supervisors, as their roles could differ per company. In the first round, 30 employers indicated their willingness to participate in an interview. Because most respondents represented medium and larger companies, we conducted a second round of sampling; in this round, the UWV sent letters to 100 employers with smaller companies, who had since 2017 retained only one worker with residual work capacities.

Procedure

In-depth interviews with the employer representatives were conducted in 2019, either face-to-face or by telephone. JJ conducted all interviews, and had not previously met the employers in person. The employers had no connection with the UMCG. Employers were asked to prepare information about at least one case of a worker with disabilities who successfully (partially) stayed at work. Before being interviewed, employers filled in a small questionnaire to provide background information about: (1) their sector of employment, (2) their function, (3) the date of disability benefit assessment in the case they had prepared, (4) the type of disability of the case, (5) their number of years of experience in this job, (6) their company size, and (7) whether the employer was insured for sick leave costs (yes/no). The interview guide was structured according to the different phases of the RTW trajectory; questions were about what actions employers had taken at the onset of their worker’s sick leave, and what happened during the period of long-term sick leave (6–8 weeks to 2 years) as well as during the period after 2 years of sick-leave, when the worker applied for disability benefits. For each phase questions started with, “What did you do?”; follow-up questions included: “How did you feel about it?”, “How did the worker with disabilities feel about it?” and “How was the interaction between you and the worker?” The interviews lasted 60–120 min.

Analyses

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and entered in Atlas.ti 8.4 for analysis. We used qualitative thematic analysis to guide the research analyses [28]. We conducted thematic analyses by developing a systematic coding process to identify themes and patterns in the data. The thematic coding scheme was based on themes retrieved from a previous systematic review conducted by our team [29]; from an article on the “Reasonable Accommodation Factor Survey” [30]; and on additional codes retrieved from the transcripts. Memos made during and directly after the interviews helped to identify the saturation point of the themes. In addition to thematic coding, we used open coding. After this, we revised the coding scheme for clarification and added new codes, clustering thematically similar codes into broader codes. JJ coded all transcripts. To establish credibility, first a co-researcher (NS) independently coded three transcripts and in addition a researcher specialized in qualitative research (MA) also independently coded three interview transcriptions and discussed and compared the code scheme with JJ. This led to a revised code scheme, which was then shared with and controlled by members of the research team (CB, SB). Together with the research team, we made the final decisions regarding the clustering of the coding in themes. After clustering the codes into themes, we analyzed relationships between themes, and differences within themes, like opposite perspectives. In addition, we clustered types of employer support per RTW phase.

Results

Sample Describing

Employer representatives included in the interviews were case managers (10), HR managers and P&O advisors (9), supervisors (6), and reintegration specialists within the organization (2), 16 of whom were employed in the public sector and 11 in the private sector. The employer representatives were all from different organizations and employed in different regions in the Netherlands. Of the employer representatives, ten were male and 17 were female. In addition, six had one to five years of work experience, seven had six to ten years of experience, and 14 had ten or more years of experience (Table 1). Each employer reported on one or more cases of workers with disabilities, most of whom had long-term physical disabilities (32), and some had mental health problems (6).

Themes and Subthemes

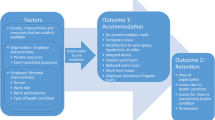

Analysis of the supportive role of employers resulted in two categories: types of support and facilitators of support, with several themes and subthemes related to each overarching theme. Figure 1 presents a visualization of the themes and subthemes. To illustrate the findings we added representative quotes from the employer representatives, translated by a native English speaker.

Types of Support

Participants reported three different types of support which they could offer to the worker with disabilities: instrumental support, emotional support and informational support.

Many employers stated the importance of offering work accommodation as part of instrumental support. Work accommodations can be arranged formally or informally. Formal work accommodations include changing working hours, changing work tasks, and allowing working from home. Some employers reported that this type of support was easily implemented, especially when they perceived no barriers from the workplace and colleagues against providing work accommodations. Conversely, other employers noted that it was difficult to provide formal work accommodations, because arranging and implementing effective and suitable work accommodations takes a lot of time and effort, and also depends on the availability of job functions within the organizations. I12: “…whereas in an office you can still easily just work 3.5 hours. In a production line we work in blocks until breaktime. I can easily call in an agency worker for half a day, for example, but I can’t call in an agency worker for just 1.5 hours a day. In terms of planning, in a production environment you are less flexible with the part-time arrangements you can offer employees. So there you have to discuss a bit more, also with the company doctor, as to what fits in terms of a part-time model.” [HR manager, industry] Some employers also expressed that changing work tasks was not a structural solution, as within their organization it was impossible for them to create a new function. Therefore, some employers mentioned that providing a new function to a worker with disabilities is just dependent on luck: I8 “Yes, sometimes it’s just a matter of timing. You know, at the moment a person can no longer do his job, then he becomes a candidate for reintegration. That means that he has precedence over others for suitable job openings that become available.” [HR manager, health care].

Employers often considered informal work accommodations helpful, as when co-workers could take over tasks for the sick colleague and create a (temporarily) new (previously non-existing) function. I15: “Look, if you, if more people are doing the same job, then you can arrange with colleagues, like, take over for each other when one is sick. And if that doesn’t give any problems, then you get very nice cases.” [case-manager, health care]. However, when informal work accommodations became structural, some employers perceived negative effects, such as stress among co-workers. I10: “Then I kind of wonder, what if you limit the flexibility [and] continuity of … the different workstations that we have to distribute our employees over? In which case the heavy workstations, the activities that definitely have to be done, end up with the more healthy people. And in itself that’s not bad for a while, but if that continues, then in my experience you end up in a negative spiral. Because then you’re going to overburden the healthy people, and they’ll drop out.” [supervisor, industry].

Besides instrumental support, many employers mentioned the importance of emotional support. They reflected that their encouragement of workers in the RTW process, by showing empathy and understanding and taking the other seriously, could help these workers to succeed in the RTW process. I11: “I find involvement with people, knowing about people and showing interest in them, and thinking with them and being much more encouraging and positive, works better than putting them on the spot and being critical. I think that’s just the crux of how you should do things. And then a lot of things just go well, and where possible you look together for a solution. And usually there is one.” [HR manager, education] However, many employers emphasized that in some RTW trajectories it is necessary to guard against going along with the needs and wishes of the workers, because this can sometimes impede their RTW and recovery. Many expressed the need to be clear about expectations.

The third type of support, informational support, usually had to do with providing information about laws and regulations and available disability and prevention interventions, and with providing support for the disability assessment. Disclosure about these themes revealed possibilities for work accommodation. I12: “…and sometimes they have questions that I can’t answer, either. But then they’ve said it, then it’s out, you know, then it’s out of their head and then maybe I can refer them; I can say well, you’d better call UWV, or let’s, shall we, call the UWV together…. Then they have the idea that they have a kind of supporter, so to speak, and that if they have doubts about something or still have some worries, they can express it and we can just talk about it together. And you really mustn’t imagine that we spend hours and hours on this; I mean, it all sounds very dramatic and spectacular, but it’s not. Sometimes it’s just a quarter or half an hour of coffee together, like hey, if you have any questions about it… You know, let’s take this step now. I’ll also confirm it in a letter. If you have any questions about it, call me or just drop by.” [HR manager, industry] Employers regarded informational support as one of their responsibilities, especially because not every worker with disabilities is able to receive and understand the information him- or herself, and often RTW is complicated. Therefore, employers expressed the value of spending time to explain, for example, the required roles of the employer and the worker, as well as possible interventions and work accommodations. I13: “And then while you’re talking about it, you realize that, yes, as long as I’m not sick, I’m not going to read all that. So only when someone becomes really long-term sick, yes, then they start scratching their heads and thinking, oh well, problem analysis and action plan … Only then do people think, oh yes… I also have to deal with that. And I don’t know if it’s because most of the people I work with come from a production environment. But, yes, also on other levels. Then I notice that, well, it’s quite a lot of paperwork. And I think it’s best to just take people through it step by step.” [case manager, industry] Employers also mentioned that informational support includes setting boundaries for workers, such as explaining that they may be too ambitious in trying to (fully) return to work. I17:”… Look, and the best thing is if they as supervisors know someone well and know what works with them, that is, that one person you have to stimulate a bit and the other you have to slow down; to the one you have to give space and respect their autonomy, and to the other you have to give more guidance.” [P&O-advisor, health care].

Differences in Support Between the Phases

Formal instrumental support was relevant in all RTW phases. Informal support was mostly relevant in the first phase, but became more structural in the second phase. Emotional support was reported as relevant in all phases, but during follow-up its focus changed: in the first phase of sick-leave, support focused on getting a grip on the situation, followed by a focus on understanding the needs of the workers during the second phase of RTW. Post-RTW, after the disability benefit assessment, emotional support was about staying engaged with the worker in order to respond to possible changes in his needs. Informational support was mentioned as particularly relevant during the first two phases of RTW. Such support changes from providing information about RTW and the plans to be undertaken, towards providing information and support for the disability assessment.

Facilitators of Employer Support

Collaboration

To provide the different types of support, most of the employers mentioned good collaboration as an important aspect, relevant to all phases of the RTW process. The analyses revealed that these facilitators are overarching factors of support and are relevant in all phases of the RTW process. Four subthemes of collaboration were identified: (in)formal contact, communication, trusting relationships, and mutual responsibilities.

Having (in)formal contacts was reported as an important facilitator for good collaboration. Contact moments can be organized formally, as prescribed by law. Such formal contacts are important for the official process of RTW and for accommodating work to bring about sustainable RTW. However, employers also expressed the importance of staying in touch with the sick-listed worker in the time between the formal contact moments. I18: “And nothing happens, while in the meantime the employee is recovering and can do more, yes, then you encourage that, and I think that’s good for both sides. And then the obstacle becomes a little smaller if you just stay in touch every time.” [HR manager, other].

Open communication characteristically provides clarity about what employers expect from the worker during the trajectory, and about possibilities for work accommodations. Although many employers remarked that it did not always feel good to be clear, they recognized the benefits of open and clear communication. According to the employers such communication helps workers to accept their work disability and adapt their expectations regarding accommodations. Another aspect mentioned in regard to open communication was disclosure. Some employers mentioned the importance of asking critical questions to help workers to be open about their disabilities, their feelings, and their concerns regarding sustainable RTW. I11: “… ask more critical questions, like what do you need to get through this difficult period? Will it help you to stay at home, or would distraction be better for you?” [HR manager, education] Such disclosure can help supervisors to devise work accommodations to fit the personal circumstances of the sick-listed worker. Employers also initiated disclosure by asking whether workers wanted to tell their colleagues what was happening and what they needed.

Many employers consider a trusting relationship between the supervisor and the worker to be important for good collaboration. A perceived lack of trust complicated efforts to make agreements, and to create alignment and open communication. Some employers consider trusting relationships with workers to be a part of their organizational culture. Active listening and reflection can also help to build trust and provide clarity about the trajectory and the future. One employer described how it worked when workers trusted her: I12: “And then just say, gosh, I’m really having problems with this now, can you think through it with me, or do you know how this works, that at a certain point they themselves seek contact when they have a question or just want to share something confidential or just tell how they are doing.” [HR manager, industry].

Many employers felt that, to determine the process of the RTW trajectory, the employer and worker have mutual responsibilities; these are considered to be another key aspect of collaboration. All employers explained that both employer and worker need to think about possibilities for work accommodations, and take responsibility to fulfill mandatory requirements of the Dutch Gatekeeper Improvement Act. Employers also expressed that workers are responsible to communicate what they need from the employer: I13: “And are there still other things I haven’t thought about, uh, that you need? And if there aren’t now, yes, let me know later. Because yes, that part is your own responsibility…” [case manager, industry] They also mentioned that both employer and worker are responsible for a positive attitude during the trajectory; to make the trajectory easier, both should look for possibilities rather than focusing on the negative aspects of disability and RTW. I14: “Well, I didn’t discuss with him what he expected from his employer. We just did what had to be done and later he said he was thankful for that, so that’s actually a yes, but okay, his cooperation during the whole process showed that he was very satisfied with it and considered it a good solution. So, because he went along with the solution offered by the employer and didn’t act difficult if the schedule wasn’t just the way he wanted, and then get annoying, but just collaborated, went along, was cooperative, made an effort where possible, yes. That showed that, of course, that he was showing his gratitude.” [case manager, education].

Employer Characteristics

Along with support and collaboration, employers mentioned organizational culture, leadership skills and flexibility on the part of employers, as well as (in)formal networks, to be important employer characteristics influencing the RTW trajectory of workers with disabilities. The analyses revealed that some of these factors are more relevant at the second and third RTW phase, especially the use of (in)formal networks.

Employers explained that a supportive organizational culture plays a role in how they approach the worker with disabilities. They expressed the importance of having a people-oriented approach, to see the worker as a human being instead of only a human resource: I16: “…a culture where primarily one person, or only the result, counts and people ignore the relationship, is disastrous for absenteeism. Yes. That’s a huge contributor to absenteeism. So sincere contact, daring to make a difference and stepping outside the box for a short period of time, helps you to get an absent employee back much faster than when you don’t dare and don’t have the guts to do that.” [case manager, finances] According to employers, organizational culture consists of the unspoken rules on how employers and workers relate to each other, and expectations about work ethos. Some said that every worker in their organization knew the importance for the organization of open communication and taking care of each other. Moreover, in some organizations in the health sector, but also in ICT, government and education, reputation (status, image) is an important aspect of the organizational culture. The representatives of these organizations mentioned that status ensures that workers really want to continue employment within their own functions in these organizations.

Some employers mentioned that supervisors need leadership skills for collaborating with workers with disabilities and professionals: skills like communication, confidence, reflection, and the ability to share their personal experiences. Among helpful leadership skills they included not being afraid to communicate about responsibilities for and barriers to work accommodations. In addition, some employers found it useful to be unafraid to make early decisions about how to approach the trajectory. Many employers expressed the urge to give their best in their support: I19: “Then I’m really a terrier, if things are really unreasonable and unfair. Then I get my teeth into it and then I can be a tough customer. Then I go for it for my employees, to get the very best for them.” [supervisor, education] A few employers also said that besides having a professional side, they also had a soft side. Some mentioned that their own reflection on the personal circumstances of the worker could influence the trajectory. In addition, some considered it important to consider their own past personal experiences with work disability.

Another important employer characteristic was flexibility, reported as valuable to help employers to consider alternative solutions and provide tailor-made approaches, rather than sticking to strict boundaries and time restrictions within trajectories. Tailor-made approaches include deciding to start earlier with mandatory actions, like involving external professionals. Some employers illustrated the importance of flexibility in making individual decisions for workers, rather than focusing on equality for all workers. I9: “Because in some places the pressure to produce is so high, and employees are constantly confronted with production demands that have to be met. Can you be a little flexible in this, and do you dare to make different arrangements with the one than with the other? Or do you treat everyone the same, and do they all have to meet the same production goals?” [HR manager, health care].

Human capital was reported as another important aspect. Many employers expressed that, although they prefer not to make exceptions for workers who show that they like to work hard and who are valuable to the organization, such an attitude certainly helps. Some employers tend to do more for workers who are more valuable, especially because they have been employed for many years. I12: “Of course you also consider that someone has already worked here for 25/30 years. Highly valued employee, someone you never heard or saw, just a silent force, yes, and then you sit down at the table together, let’s just do all we can to keep her here. For sure, let the boss know if you really can’t manage it. But from the beginning he has already taken the position of, let’s see if we … in any case can keep her for the organization.” [HR-manager, industry].

Many employers mentioned the importance of having their own formal and informal networks with other supervisors or HR managers as a facilitator of job retention. Networks can include contacts within the same organization or within other organizations. Particularly when workers are not capable of returning to their own jobs despite the provided work accommodations, it is important to support them to find another job, one better suited to their residual work capacity. Such networks should be established in advance, because it takes time and effort to create a network. I11: “From all kinds of sectors we have employers who regularly sit down together to see what vacancies are available. If we have people working for us who are for some reason no longer suited to their position, maybe they could gain very good experience or even a job with another employer in our network.” [HR manager, education].

Worker Characteristics

Employers considered flexibility and self-control on the part of workers as important facilitators of the RTW trajectory. They mentioned the advantage of having workers willing to adapt to changes in the trajectory and accept work accommodations. I9: “Well, in practice we always know how to redeploy people. And whether that works depends a lot, I think, on how flexible the employee is. And whether he has had fairly good training. Some people want to know exactly where they stand. Well, in such a situation you don’t know where you stand. That can take a while. We try to offer possibilities, sometimes temporary, but then you still don’t have a definite position. The more easily a person deals with this, the sooner he will have a place.” [HR manager, health care].

Many employers appreciated having workers show self-control expressing what they need and want. Employers admire this quality because it is convenient for themselves; they do not have to invest time and effort to activate these workers. A few employers explained that they promote workers’ self-control by offering training. I17: “Some employees are very good at deciding for themselves what helps them, what they are capable of. They are able to think, what does it mean for my colleagues to have to take over certain tasks in my absence? … That differs a lot per employee and you really want, that’s the purpose of the program sustainable deployment but also training and education, that in principle the employee can do this. Because then he remains in charge. But not everyone can manage that.” [P&O advisor, health care] Some employers also remarked that, because of their character traits and personal circumstances, not all workers are able to show self-control. I20: “Ostrich politics. Trying to deny that you may have something really bad. Trying to hide that. You’re ashamed. You don’t want to walk around like a loser. You want to be a big girl. Maybe you don’t see that so clearly anymore either … So it depends a lot on yourself. Hey, when do you say: hey, I’ve come to the point that I can’t go on? And I need help with that?” [supervisor, finances] Some employers expressed that when workers are flexible and show self-control, the role of the employer is much easier because he does not have to work hard to stimulate them.

Discussion

This interview study describes the actual experiences of a wide-range of employers who successfully helped workers with disabilities to stay at work. We focused on employer perspectives on long-term RTW trajectories of workers with both mental and physical work disabilities. We have identified that employers who successfully supported these workers provided formal and informal work accommodations, showed empathy and understanding, and facilitated disclosure and provided information and boundaries. We have also identified that employers experienced several facilitators as helpful during the RTW process: (1) good collaboration, including (in)formal contact, trustful relationships, mutual responsibilities; (2) employer characteristics, including supportive organizational culture, leadership skills, organizational flexibility, and (in)formal networks; and (3) worker characteristics, including flexibility and resilience. In all phases, formal instrumental and emotional support were found to play a role, albeit in different ways.

With our study we explored what kind of employer support is relevant for RTW. This is in line with previous studies that also found the importance of different types of support, which they framed as instrumental, emotional and informational support [9, 11, 31, 32]. These studies, mostly from the perspective of the workers, also found that empathy, trust, guidance are important aspects in the RTW process [11, 31]. Our study builds on this knowledge by providing information about barriers and facilitators to provide employer support from an employer perspective. Moreover, we were able to include a 2-year sick leave and RTW process, whereas previous qualitative studies focused on a shorter period [9]. Studies that did focus on the three phases, including sustainable RTW, showed some similar findings regarding concrete actions employers undertake [16, 33,34,35]. For example, our study showed that emotional support is critical throughout the RTW process, similar to a study by [11], but different from a study [36] who found that the emotional support from supervisors is relevant in the RTW-phase and not in the other phases.

In addition, we found that instrumental support and informational support are also critical throughout the RTW process, but also develop over time. For instance, the provision of work accommodations depends on the RTW phase, which is also found by other studies [16, 35]. Our study differs in the finding that employers can implement the instrumental support in an informal and formal way. We found that some employers implement informal support, by means of co-workers taking over tasks. In addition, our study showed that besides the concrete actions that are mainly related to the implementation of work accommodations, other factors like collaboration are critical as well.

The importance of providing work accommodations is in line with previous studies. A recent systematic review on the role of the employer in supporting work participation by workers with disabilities, gave moderate to strong evidence of the benefits of work accommodations like adjusted work schedules, provision of equipment, and modified work activities to help workers to return to work, and to stay employed after the onset of work disability [29]. Informal instrumental support, as by coworkers who are willing to take over work tasks, has been identified as a substantial type of work accommodation, both vital and easy to implement during the first phase of sick leave. This applies particularly in cases when arranging formal work accommodations is hindered by obstacles within the organization, or when work accommodations that fit the needs and skills of the worker are hard to find. However, using informal support as a structural solution can put a burden on healthy co-workers [12, 37, 38], especially when employers are unaware that co-workers are providing such support because it is often ‘behind the scenes’ [39]. Such factors may leave less leeway for arranging formal work accommodations, and also negatively affect the well-being of the healthy co-workers.

The importance of offering emotional and informational support was also reported in previous studies. Workers found emotional support by the supervisor to be particularly effective in diminishing their feelings of vulnerability during RTW [40, 41]. A supervisor who showed empathy and understanding helped them to adapt better to their new situation. Research on workers with a burn-out also showed that emotional support changed the focus from the pressure of RTW to the recovery that was needed [32]. Informational support includes the role of employers to inform their workers of the rules and legislations related to the RTW process [11]. Most workers do not have advance knowledge about sick leave regulations and disability benefit claim procedures [39]. If individuals do not understand or correctly perceive the incentives and possibilities, they may make suboptimal decisions [42]. Employers can thus play an important role in communicating this information to workers during all phases of the RTW process, including the final phase when the worker needs to submit the necessary documents for the disability claim assessment.

Among the factors facilitating RTW, our study underlines the significance of the interaction between supervisor and worker. To make such collaboration effective, frequent (in)formal contact, trustful relationships, and mutual responsibilities were found to be essential. Skilled supervisors are thus a vital part of employer support during the RTW process [32, 43]. Several other studies also emphasized the importance of organizational culture, flexibility, and leadership skills at the employer level [44, 45], as well as disability management policies and practices in the workplace [45, 46]. Other studies from the perspective of workers also found that communication is an important aspect during RTW. These studies mainly focused on the role of health care providers and showed that meaningful communication between health care providers and employers is important [47]. In addition, a study showed that workers who were successfully accommodated within their organization described the importance of good communication with the supervisor as well [48]. Along with above-mentioned leadership skills like empathy and understanding and effective communication, to collaborate effectively, employers, and more specifically supervisors, need to have adequate knowledge about the work circumstances of the worker [49]. In our study, along with flexibility, employers also mentioned the importance of resources like networks within and outside the organization as important sources of support for workers with disabilities. Other studies also showed that employers use networks to share knowledge and experiences about diseases and practices [50, 51]. However, as yet, no available literature describes how employer networks can be used in RTW processes, such as finding (temporary) jobs within other sections of the organization, or in other organizations. Furthermore, the characteristics and attitudes not only of employers, but also those of workers, were found to influence employer support. We found that workers who showed flexibility and self-control were more likely to receive support from their employers, thereby facilitating the RTW process. Other qualitative studies also mentioned that workers’ self-control [52, 53], and their ability to express their needs, were facilitators of RTW and staying at work.

Strengths & Limitations

An important strength of the present study is that it explored the support of workers in RTW from the employer’s perspective. Moreover, this study is augmented by success stories of employers of workers with disabilities, as we selected employers who had managed to retain one or more of these workers within their organization. Although we focused on success stories we also received information about challenges that employer representatives perceived during the RTW process. However, studies who investigated barriers for RTW also revealed other themes that could be helpful to understand why some workers are able to sustainable RTW and others not. These studies focused on barriers and facilitators of workers who were unable to continue working [19] and revealed themes related to personal characteristics of workers, like the financial situation, job issues but also organizational influences and the role of interpersonal support [54].

Another strength of the study is that we collected information about employer support during different phases of the RTW process. Most previous studies investigated employer support in RTW only over a short period of time, therefore including only a part of the employer’s role in the process. Our study followed the role of the employer from the first phase of sick-leave and RTW up to and after the disability claim assessment. We were thus able to provide an overview of employer support during different RTW phases. As we investigated the role of the employer in every phase of RTW, future research could shed more light on these different phases.

In addition, a strength of our research is the heterogeneity of our study sample. We interviewed a variety of employer representatives, supervisor, casemanagers and HR managers, from small to large organizations in both public and private sectors, from almost all regions of the Netherlands. The variety in differences in jobs occurred because employer support is organized differently in organizations. After analyzing the transcripts, we confirmed that all the different representatives provided the types of support during the RTW process.

However, this heterogeneity had some limitations, one being that the design of this study did not allow us to investigate the differences in the roles of the representatives. In future research it would be interesting to further explore whether the different employer representatives are equally involved at all phases and whether the type of provided support differs. In addition, this study explores the perspectives of employer representatives who are involved in return to work (RTW) planning for workers with disabilities who have been on sick leave. We focused only on the perspective of the employer which could be a limitation of the study. Including the perspectives of other stakeholders such as occupational health physicians and stakeholders outsight the organization such as labor-experts might give a bigger picture of employer support. One limitation of our study is that we did not explore the experiences of dyads of workers and employer representatives in this study. This exploration could have brought more insight into the challenges and successes perceived by the workers and supervisors and how this developed during the RTW phases. Future research is needed regarding linking the perspectives of workers with disabilities and their employers on how they can facilitate more sustainable RTW; such research is yet scarce. With the exploration of experiences of these dyads, future research could evaluate the supervisor-worker relationship in more detail. In addition, future research could investigate which supportive employer factors are interrelated, and how they influence each other.

Another limitation of our study is that our employer representatives selected more cases of workers with long-term physical disabilities like cancer and heart and cardiovascular diseases, than workers suffering from mental health problems like depression and anxiety. Workers with mental health problems often need other, and more extensive, work accommodations than workers with physical disabilities [55]. Our findings may thus not be fully applicable to workers with mental health problems. This limitation maybe be linked to the strength of our study that we focused on success stories, maybe the employers only picked cases that were easier to accommodate to the workplace. Which could have resulted in a selection of cases of workers with physical health problems. However, a strength of our study is that we investigated employer support for workers who have partial work capacities and receive disability benefits, which is not often being investigated. Future research could focus on the differences in employer support between workers with physical disabilities and workers with mental health disabilities.

Implications

The role of employers at all levels, from management to supervisors, is important to help workers with disabilities to stay at work. Their provision of instrumental, emotional, and informational support is essential. Emotional and informational support help employers to build a trustful relationship with workers and to provide advice tailored to their needs. It is, therefore, important for employers to develop certain tools if they are to implement the three types of support effectively. One implication of this study is that although support is relevant in all stages of the RTW process, different stages may require different forms of support. Employers need to realize this already during the first phase of RTW. Moreover, collaboration is an important facilitator of all three types of support. HR managers play a large role in improving informational support, for example by educating supervisors in policies and legislations. Also, collaboration with other stakeholders involved in the RTW trajectories makes it easier for employers to arrange work accommodations. Furthermore, regarding employer characteristics, it is helpful when employers focus more on possibilities than on disabilities and barriers. It can also help if they invest in individual and organizational networks, inside and outside the organization.

Conclusions

Throughout the RTW process of workers with disabilities, different types of employer support are important. During sick leave, the RTW process, and for sustainable employment, workers need work accommodations, but also emotional and informational support. Good collaboration and flexibility on the part of both employer and worker are facilitators of optimal interaction during the RTW process. The varying content of employer support over time suggests that RTW is a complex process, indicating the relevance of further investigation. This study underlines the importance of employer support for workers with disabilities, and shows that it should be tailored to the needs of both the employer (i.e., management and supervisors) and the individual worker with disabilities. The type and intensity of employer support varies during the different phases, which is a finding that should be further investigated. In addition, more insight is needed on how this supervisor/worker interaction develops during the RTW process.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

OECD. Sickness, Disability and Work - A Synthesis of Findings across OECD Countries. 2010. 1–556 p.

Burkhauser R, Daly M, Ziebarth N. Protecting working-age people with disabilities: experiences of four industrialized nations. J Labour Mark Res. 2016;49:367–386.

Clayton S, Barr B, Nylen L, Burstrom B, Thielen K, Diderichsen F, et al. Effectiveness of return-to-work interventions for disabled people: a systematic review of government initiatives focused on changing the behaviour of employers. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(3):434–439.

Böheim R, Leoni T. Sickness and disability policies: reform paths in OECD countries between 1990 and 2014. Int J Soc Welf. 2018;27(2):168–185.

Organization WH. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health World Health Organization Geneva ICF ii WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. 2001.

Corbière M, Negrini A, Dewa CS. Mental health problems and mental disorders: Linked determinants to work participation and work functioning. In: Handbook of Work Disability: Prevention and Management. Springer New York; 2013. p. 267–288.

Shaw WS, Main CJ, Pransky G, Nicholas MK, Anema JR, Linton SJ. Employer policies and practices to manage and prevent disability: foreword to the special issue. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(4):394–398.

MacDonald-Wilson KL, Fabian ES, Dong S. Best practices in developing reasonable accommodations in the workplace: findings based on the research literature. Rehabil Prof. 2008;16(4):221–232.

Negrini A, Corbière M, Lecomte T, Coutu M-F, Nieuwenhuijsen K, St-Arnaud L, et al. How can supervisors contribute to the return to work of employees who have experienced depression? J Occup Rehabil. 2017;28(8):279–288.

Mansfield E, Stergiou-Kita M, Kirsh B, Colantonio A. After the storm: the social relations of return to work following electrical injury. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(9):1183–1197.

Lysaght RM, Larmour-Trode S. An exploration of social support as a factor in the return-to-work process. Work. 2008;30(3):255–266.

Kristman V, Boot C, Sanderson K, Sinden K, Williams-Whitt K. Implementing best practice models of return to work. In: Handbook of Disability, work and health. 2020. p. 1–25.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Verbeek AM, De Boer EM, Blonk RWB. Supervisory behaviour as a predictor of return to work in employees absent from work due to mental health problems. Occup Env Med. 2004;61(10):817–823.

Gignac MAM, Kristman V, Smith PM, Beaton DE, Badley EM, Ibrahim S, et al. Are there differences in workplace accommodation needs, use and unmet needs among older workers with arthritis, diabetes and no chronic conditions? Examining the role of health and work context. Work Aging Retire. 2018;4(4):381–398.

Durand M-J, Corbiere M, Coutu M-F, Reinharz D, Albert V. A review of best work-absence management and return-to-work practices for workers with musculoskeletal or common mental disorders. Work. 2014;48(4):579–589.

Nastasia I, Coutu M-F, Rives R, Dubé J, Gaspard S, Quilicot A. Role and responsibilities of supervisors in the sustainable return to work of workers following a work-related musculoskeletal disorder. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;31(1):107–118.

Stahl C, Edvardsson Stiwne E. Narratives of sick leave, return to work and job mobility for people with common mental disorders in Sweden. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(3):543–554.

Corbiere M, Samson E, Negrini A, St-Arnaud L, Durand M-J, Coutu M-F, et al. Factors perceived by employees regarding their sick leave due to depression. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(6):511–519.

Dionne CE, Bourbonnais R, Fremont P, Rossignol M, Stock SR, Laperriere E. Obstacles to and facilitators of return to work after work-disabling back pain: the workers’ perspective. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(2):280–289.

Holmgren K, Synneve ·, Ivanoff D. Supervisors’ views on employer responsibility in the return to work process. A focus group study. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17:93–106.

Nastasia I, Coutu M-F, Rives R, Dubé J, Gaspard S, Quilicot A. Role and responsibilities of supervisors in the sustainable return to work of workers following a work-related musculoskeletal disorder. J Occup Rehabil. 2020;31:107–118.

Tiedtke CM, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Frings-Dresen MHW, De Boer AGEM, Greidanus MA, Tamminga SJ, et al. Employers’ experience of employees with cancer: trajectories of complex communication. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(5):562–577.

van Beurden KM, Joosen MCW, Terluin B, van Weeghel J, van der Klink JJL, Brouwers EPM. Use of a mental health guideline by occupational physicians and associations with return to work in workers sick-listed due to common mental disorders: a retrospective cohort study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;40(22):1–9.

Government of the Netherlands. Wet verbetering poortwachter [Internet]; 2008 [cited 2021 May 13]. Available from: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0013063/2008-11-01.

Government of the Netherlands. Wet werk en inkomen naar arbeidsvermogen (Work and Income Act) [internet]; 2005 [cited 2022 January 4]. Available from: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0019057/2020-03-19.

Everhardt TP, de Jong PR. Return to work after long term sickness. Economist (Leiden). 2011;159(3):361–380.

Muijzer A, Groothoff JW, Geertzen JHB, Brouwer S. Influence of efforts of employer and employee on return-to-work process and outcomes. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(4):513–519.

Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. In: Encyclopedia of critical psychology. Springer New York; 2014. p. 1947–1952.

Jansen J, van Ooijen R, Koning PWC, Boot CRL, Brouwer S. The role of the employer in supporting work participation of workers with disabilities: a systematic literature review using an interdisciplinary approach. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;31(4):1–34.

Dong S, Macdonald-Wilson KL, Fabian E. Development of the reasonable accommodation factor survey: results and implications. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2010;53(3):153–162.

Seiger CP, Wiese BS. Social support, unfulfilled expectations, and affective well-being on return to employment. J Marriage Fam. 2011;73(2):446–458.

Kärkkäinen R, Kinni RL, Saaranen T, Räsänen K. Supervisors managing sickness absence and supporting return to work of employees with burnout: a membership categorization analysis. Cogent Psychol. 2018;5(1):1–17.

Corbière M, Mazaniello-Chézol M, Bastien MF, Wathieu E, Bouchard R, Panaccio A, et al. Stakeholders’ role and actions in the return-to-work process of workers on sick-leave due to common mental disorders: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2020;30:381–419.

Greidanus MA, Tamminga SJ, de Rijk AE, Frings-Dresen MHW, de Boer AGEM. What employer actions are considered most important for the return to work of employees with cancer? A Delphi study among employees and employers. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(2):406–422.

Petersen KS, Momsen AH, Stapelfeldt CM, Nielsen CV. Reintegrating employees undergoing cancer treatment into the workplace: a qualitative study of employer and co-worker perspectives. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(4):764–772.

Graff HJ, Deleu NW, Christiansen P, Rytter HM. Facilitators of and barriers to return to work after mild traumatic brain injury: a thematic analysis. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2021;31(9):1349–1373.

Dunstan DA, Mortelmans K, Tjulin A, Maceachen E. The role of co-workers in the return-to-work process. Int J Disabil Manag. 2015;10(2):1–7.

Dunstan DA, Maceachen E. A theoretical model of co-worker responses to work reintegration processes. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(2):189–198.

Tjulin Å, MacEachen E. The importance of workplace social relations in the return to work process: a missing piece in the return to work puzzle? In: Handbook of return to work. 2016. p. 81–97.

Tiedtke C, Dierckx de Casterle B, Donceel P, de Rijk A. Workplace support after breast cancer treatment: recognition of vulnerability. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(19):1770–1776.

Gray S, Sheehan L, Lane T, A J, Collie A. Concerns about claiming, postclaim support, and return to work planning: the workplace’s impact on return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2019;61(4):139–145.

Liebman JB, Luttmer EFP. Would people behave differently if they better understood social security? Evidence from a field experiment. Am Econ J Econ Policy. 2015;7(1):275–299.

Jetha A, Yanar B, Lay AM, Mustard C. Work disability management communication bottlenecks within large and complex public service organizations: a sociotechnical systems study. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(4):754–763.

De Rijk A, Amir Z, Cohen M, Furlan T, Godderis L, Knezevic B, et al. The challenge of return to work in workers with cancer: employer priorities despite variation in social policies related to work and health. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14:188–199.

McGuire C, Kristman VL, Shaw WS, Loisel P, Reguly P, Williams-Whitt K, et al. Supervisors’ perceptions of organizational policies are associated with their likelihood to accommodate back-injured workers. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(4):346–353.

Friesen MN, Yassi A, Cooper J. Return-to-work: the importance of human interactions and organizational structures. Work. 2001;17(1):11–22.

Kosny A, MacEachen E, Ferrier S, Chambers L. The role of health care providers in long term and complicated workers’ compensation claims. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(4):582–590.

Williams-Whitt K, Taras D. Disability and the performance paradox: can social capital bridge the divide? Br J Ind Relat. 2010;48(3):534–559.

Johnston V, Way K, Long MH, Wyatt M, Gibson L, Shaw WS. Supervisor competencies for supporting return to work: a mixed-methods study. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):3–17.

Coole C, Drummond A, Watson PJ. Individual work support for employed patients with low back pain: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(1):40–50.

Holmlund L, Hellman T, Engblom M, Kwak L, Sandman L, Törnkvist L, et al. Coordination of return-to-work for employees on sick leave due to common mental disorders: facilitators and barriers. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;1–9.

Bosma AR, Boot CRL, Schaafsma FG, Anema JR. Facilitators, barriers and support needs for staying at work with a chronic condition: a focus group study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:201.

Bosma A, Boot C, De Maaker M, Boeije H, Schoonmade L, Anema J, et al. Exploring self-control of workers with a chronic condition: a qualitative synthesis. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2019;28(5):653–668.

Hartke RJ, Trierweiler R. Survey of survivors’ perspective on return to work after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2015;22(5):326–334.

Boot C, van den Heuvel S, Bültmann U, de Boer E, Angela G, Koppes L, et al. Work adjustments in a representative sample of employees with a chronic disease in the Netherlands. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(2):200–208.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Nicole Snippen, who independently coded three transcripts.

Funding

This work was supported by Instituut Gak, Grant Number 2018-933.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation were performed by Joke Jansen, Cécile Boot and Sandra Brouwer. Data collection was performed by Joke Jansen. The analysis were performed by Joke Jansen and Manna Alma. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Joke Jansen and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors JJ, CB, MA, and SB have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was received from the Medical Ethical Review Board (METc) of the University Medical Center Groningen.

Consent to Participate

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jansen, J., Boot, C.R.L., Alma, M.A. et al. Exploring Employer Perspectives on Their Supportive Role in Accommodating Workers with Disabilities to Promote Sustainable RTW: A Qualitative Study. J Occup Rehabil 32, 1–12 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-021-10019-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-021-10019-2