Abstract

The lack of knowledge regarding the roles and actions of return to work (RTW) stakeholders create confusion and uncertainty about how and when to RTW after experiencing a common mental disorder (CMD). Purpose The purpose of this scoping review is to disentangle the various stakeholders’ role and actions in the RTW process of workers on sick-leave due to CMDs. The research question is: What is documented in the existing literature regarding the roles and actions of the identified stakeholders involved in the RTW process of workers on sick-leave due to CMDs? Methods In conducting this scoping review, we followed Arksey and O’Malley’s (Int J Soc Res Methodol 8:19–32, 2005) methodology, consisting of different stages (e.g., charting the data by categorizing key results). Results 3709 articles were screened for inclusion, 243 of which were included for qualitative synthesis. Several RTW stakeholders (n=11) were identified (e.g., workers on sick leave due to CMDs, managers, union representatives, rehabilitation professionals, insurers, return to work coordinators). RTW stakeholders’ roles and actions inter- and intra-system were recommended, either general (e.g., know and understand the perspectives of all RTW stakeholders) or specific to an actor (e.g., the return to work coordinator needs to create and maintain a working alliance between all RTW stakeholders). Furthermore, close to 200 stakeholders’ actions, spread out on different RTW phases, were recommended for facilitating the RTW process. Conclusions Eleven RTW stakeholders from the work, heath and insurance systems have been identified, as well as their respective roles and actions. Thanks to these results, RTW stakeholders and policy makers will be able to build practical relationships and collaboration regarding the RTW of workers on sick leave due to CMDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In industrialized countries, work disability due to common mental disorders has significantly increased over the last decade and is now the leading causes of sickness absence, and long-term work disability [1,2,3,4]. Common mental disorders (CMDs) are defined as mood, anxiety, and stress-related disorders [5] that are prevalent in the workforce, affecting 20–25% of the adult population [6,7,8]. All work absences considered, common mental disorders represent between a third and a half of all absences, depending on the sector of activity [9, 10]. Workers with CMDs who are on sick leave typically go through the process of returning to work within the same organization [6, 11]. Although working is considered as the cornerstone of one’s mental health recovery, if the return to work (RTW) is initiated too quickly or if the remission is partial when the person returns to work, the risk of relapse increases [12, 13]. Relapses typically occur within 3 years of a first sickness absence due to CMD [8] and can take the form of intermittent work disability (e.g., being unable to perform some work tasks, taking brief but frequent leaves) [14].

In addition to costs for organizations, CMDs in the workplace have negative economic consequences for society, given the indirect costs due to sickness absence, medical appointments, early retirement, and at times, early death [15]. Workers on sick leave due to CMDs are often not replaced, and consequently colleagues have to absorb additional tasks and workload [16]. Individuals with CMDs in the workplace are a growing concern for employers and society in general [17]. The World Economic Forum estimated that, by 2030, global costs of mental disorders are projected to reach six trillion US dollars; about two thirds of these costs will be attributed to lost productivity related to disability [18]. Given these astronomical costs, it is not surprising that policy makers and politicians consider CMDs as a serious public health issue and are fervently seeking solutions and strategies to implement [3, 19].

Tjulin and colleagues [20] suggested the RTW process comprises three distinct phases: off work, back to work and post-RTW sustainability. Similarly, Corbière et al. [21] suggested three phases in RTW after CMDs: (1) beginning of sickness absence and involvement of disability management team (Phase 1); (2) involvement in treatment and rehabilitation with health professionals, and preparation for RTW (Phase 2); (3) gradual return to work and follow up (Phase 3). Considering these crucial phases, sickness absence due to CMDs as well as return to work after CMDs involve a series of complex interactions and interventions enacted by multiple stakeholders. These processes take place within various environments and systems such as the workplace and the healthcare system [7, 22,23,24,25,26,27].

Even if all stakeholders have an interest in the worker achieving a safe, timely, and sustainable return to productivity, the collaboration remains difficult because each stakeholder’s role and expected actions regarding RTW after CMDs are not well defined or understood [27,28,29,30]. The literature on RTW reports that the lack of communication and coordination between the stakeholders interacting during the RTW process negatively affects the RTW and is a transversal barrier throughout the process, particularly in the case of CMDs [14, 25, 27, 31,32,33,34,35]. As the RTW process is complex and includes multiple stakeholders [19], several authors suggested categorizing them into groups based on a system theory perspective, with which the worker on sick leave interacts with: employers (work system), insurers (insurance system), and healthcare providers (health system) [30, 31]. Of note, this categorization becomes very complex when we consider that each system includes a number of different stakeholders. For instance, employers (work system) can include immediate supervisors, human resources managers, unions, and coworkers. With respect to the category of healthcare providers, general physician, occupational physicians, occupational therapists, psychiatrists, and psychologists are included [30]. Adding to the complexity, the list of stakeholders involved in the RTW depends on the context or setting. For instance, an occupational physician is often present in the RTW in European countries but optional in North of America. Unions are unavoidable in public organizations, but scarcer in the private sector.

The meta-synthesis of qualitative research on RTW of workers with CMDs conducted by Andersen et al. [36] points to a lack of coordination between stakeholders stemming from the above-mentioned systems. For instance, the health system tends to address only factors related to the mental health condition without considering potential barriers in the workplace, whereas the insurance system tends to encourage an early RTW, neglecting eventual risks of relapses due to the medical condition or psychosocial risk factors at work. The lack of coordination and knowledge regarding the roles of RTW stakeholders can cause confusion and uncertainty about how and when to return to work, with the worker at times receiving contradictory recommendations and demands regarding his health condition and RTW [36].

Clarity and consistency in RTW stakeholders’ role and actions are therefore critical for effective RTW, particularly when considering the number of stakeholders belonging to diverse systems. However, to our knowledge, in practice this information is scarce, scattered or diffused into different documents without a clear description of RTW stakeholders’ role and actions that would enable stakeholders to coordinate efficiently their efforts and evaluate the impact of their interventions. RTW stakeholder’s role was defined as attitudes to adopt in the RTW process, whereas RTW stakeholder’s actions are concrete and practical behaviors to put in place during the RTW phases. The purpose of this scoping review is to disentangle the various stakeholders’ role and actions in the RTW process of workers on sick-leave due to CMDs. To guide and build the scoping review, we seek to answer the following research question: What is documented in the existing literature regarding the roles and actions of the identified stakeholders involved in the RTW process of workers on sick-leave due to CMDs?

Methods

In order to better document the RTW stakeholders’ roles and actions regarding workers on sick leave due to CMDs, we conducted a scoping review of peer-reviewed research articles published and of the grey literature between January 1990 and January 2018, while considering systems and general RTW phases as these were inclusive to all stakeholders [21, 30, 31]. As Arksey and O’Malley [37] stated, scoping reviews aim at mapping key concepts underpinning a research area such as stakeholders’ roles and actions regarding the RTW of workers with CMDs, especially when the research area is complex or has not been reviewed comprehensively before. Furthermore, Arksey and O’Malley [37] suggested to use scoping reviews in order to visualize the range of material or results, summarize them, and disseminate these findings to policy makers, health professionals, and other stakeholders interested by the topic, while identifying gaps in the literature.

To conduct this scoping review, we followed Arksey and O’Malley’s [37] methodology. Their five-stage framework, now considered as a reference in qualitative health research and used in multiple scoping reviews in this domain [38,39,40], consists of: (1) identifying or formulating the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies by using a search strategy (e.g., electronic databases); (3) selecting the studies by creating inclusion and exclusion criteria; (4) charting the data (data extraction) by categorizing key results; and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results through tables. Finally, Arksey and O’Malley [37] recommend an optional stage to inform and validate findings in the retained articles, a ‘consultation exercise’ with stakeholders directly concerned by the topic. In the following paragraphs, we present how we have included this five-stage framework plus the consultation exercise in our study.

Identifying Relevant Articles

We used the main databases in the field of work disability studies—Pubmed/Medline, Cinahl, Cochrane, Embase, Ebsco, PsychInfo, and Scopus—with the syntax (available on demand) and the following keywords : (i) key person*, actor* or stakeholder*—e.g., “worker” OR “employee”, “coworker” OR “colleague”, supervisor* OR manager*, (ii) return-to-work*—e.g., “return to work” OR “back to work”, and (iii) Common mental disorder—e.g., mental disorder* OR anxiety* OR adjustment disorder* OR burnout*. The search strategy was developed with the assistance of a librarian in order to identify relevant articles published in the six selected databases mentioned above. A total of 4359 articles were identified through this database searching. Arksey and O’Malley [37] argue for the importance of combining electronic data bases search with hand-search to avoid (1) missing relevant literature (e.g., available Best Practices Guidelines on RTW programs, book chapters) and (2) publication bias. We systematically checked the bibliographies of systematic and literature reviews. When the studies were not in our list, we included them in the scoping process (e.g., Reavley et al. [41]). To ensure a comprehensive coverage of the literature, we hand-searched journals specialized in occupational health (more specifically mental health and work), the bibliography of articles, as well as the grey literature. This exercise leads us to add 22 articles and guidelines that met inclusion criteria. We used Zotero as a data management tool to process the study’s screening, selection, and extraction, and to follow up on the analysis of the articles.

Study Selection

After the initial search was completed, titles and abstracts were screened for relevance by four of the authors (MC, MMC, MFB, EW), using the following inclusion criteria: (1) language (English, French, or Spanish), (2) population or participants and conditions of interest (stakeholders involved in the RTW process of workers on sick-leave due to a CMD, any age or gender, any country), (3) interventions (stakeholders involved at any stages of the RTW program for workers on sick-leave due to a CMD, in or outside the organization), (4) timeframe of the intervention (people involved in the follow-up of sick-listed workers for CMDs, from the beginning of their absence until their RTW), (5) outcomes of interest (stakeholders’ roles and actions), (6) setting (large organization disability management/policies, RTW programs), and (7) study design (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed). We focused on stakeholders’ role and actions in the RTW programs for workers with CMDs. Therefore, RTW programs for workers with musculoskeletal, cancer and cardiovascular disorders as well as severe mental disorders were excluded. Also, members from the family/circle of friends of the sick-listed worker considered as stakeholders were not considered since RTW programs do not include them. Two authors (MMC and MFB) independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to all citations. When they did not reach a consensus (< 20% of records) a third reviewer (MC), was included for discussion, revision of the full article and decision until full agreement between reviewers.

Charting the Data (Data Extraction)

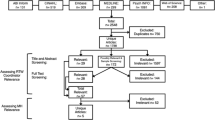

From the identified relevant articles, articles were organized into a table to read and extract the data (Figure 1 and Table 1). The research team read all the articles, extracted and synthesized the information. Secondary data extracted included information on stakeholders such as their role, actions as well as interactions between several key persons involved in the RTW process.

Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results

The first four authors of the team examined and carefully compared the retained articles to facilitate the mapping of RTW stakeholders’ roles and actions. We applied a sequential thematic analysis to gather information and identify the roles and actions, prior to summarizing and reporting the results in tables. To do so, we followed a three-stage the thematic analysis process: (1) extracting findings and coding findings for each article, (2) grouping findings (codes) according to the topical similarity to determine whether findings confirm, extend, or refute each other; and (3) abstraction of findings (analyze group findings to identify additional patterns, overlaps, comparisons, and redundancies to form a set of concise statements that capture the content of findings) [38]. First, we organized all information from the retained articles using an Excel table comprising four columns: (1) RTW stakeholders’ general role and actions in regards to the RTW process; (2) RTW stakeholders’ role and actions from a specific system, transversal to the three phases of the RTW process (3) RTW stakeholders’ actions belonging to a specific system, for each RTW phase i.e. Phase 1: beginning of sickness absence and involvement of disability management team; Phase 2: involvement in treatment and rehabilitation with health professionals, and preparation for RTW; and Phase 3: gradual return to work and follow up [21].

Then, we created tables in which we organized and summarized the information pertaining to the roles and actions of each stakeholder. The two first authors then systematically double-checked each role and action to ensure it corresponded to the ideas presented in the articles. We presented results for these 11 RTW stakeholders in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5: worker, employer/HR, manager, co-worker, union representative (work system stakeholders, Table 2), family/general physician, psychiatrist/psychologist/psychotherapist, rehabilitation professional (e.g., occupational therapist, social worker), occupational physician/nurse (health system stakeholders, Table 3), insurer (insurance system stakeholders, Table 4), and return to work coordinator (Table 5).

Consulting Exercise

This scoping review was conducted within a participatory research project, and included a consultation exercise, as recommended by Arksey and O’Malley [37]. The consultation exercise involved the RTW stakeholders involved in the participatory research project (i.e., HR, workers, managers, family physicians, rehabilitation professionals, RTW coordinators, insurers, and union representatives) who were asked to review all RTW stakeholders’ statements (roles and actions). During the course of two three-hour-long meetings, stakeholders provided valuable insights about issues relating to the RTW process of workers with CMDs. The only changes suggested by contributors were specific to the Canadian occupational environment in which they worked (e.g., they are usually no occupational physicians in Canadian organizations), and the need of clarity for some stakeholders’ statements. Since information collected in this scoping review has the potential to influence decision makers and other RTW stakeholders regarding the implementation of future RTW programs in the workplace or the community in most Western countries, we kept the description of the role of occupational physicians, given their described usefulness and common representation in many European countries. As for the wording of statements, some stakeholders found some statements pertaining to their own role and actions to be ‘basic’. However, they may not perceived as such by other stakeholders. For this reason, we decided to keep them in the scoping review. A clear description of roles and actions of each stakeholder should allow all those involved in the RTW process to have a better understanding of each other’s roles. Finally, all statements were systematically reviewed by a RTW coordinator (RB) and her team participating in the public-sector research project with the two first authors (about 3-h meeting for each stakeholder) to polish the statements and propose an accessible language for all stakeholders (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5).

Results

In the following paragraphs, brief descriptive results on papers retained in this scoping review, and results on RTW stakeholders’ roles and actions, are presented under basic/transversal across systems, and system-specific results. Finally, stakeholders’ actions for each RTW phase are briefly summarized.

Descriptive Results

In total, 4 359 abstracts were retrieved from the bibliographic databases, to which we added 22 articles from the grey literature (Figure 1). Once duplicates were removed, 3709 articles remained and were screened for inclusion, of which 243 were included for qualitative synthesis. The main characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1 (i.e., author, country, targeted RTW stakeholders). Based on the location of the lead author of studies, articles mainly originated from the Netherlands (23.9%) and other European countries (23.8%), Canada (18.9%), the United Kingdom (13.2%), the United States (9.5%), Australia (4.9%) and Japan (3.3%). The most frequently cited RTW stakeholders were workers on sick leave due to CMDs (100%), employers/HR (67.5%), managers (53.9%), occupational/nurse physicians (41.6%), family/general physicians (41.2%), psychiatrist/psychologist/psychotherapists (36.6%), rehabilitation professionals (35.0%), co-workers (32.1%), insurers (25.9%), return to work coordinators (13.6%), and unions representatives (11.1%).

RTW Stakeholders’ Roles and Actions—Basic/Transversal Results Across Systems

After reading all 243 papers, basic and transversal components, regardless of the type of RTW stakeholders, related to roles and actions emerged, namely: (1) Know and understand the role and perspectives of all stakeholders involved in the worker’s RTW process depending on the context of that workplace; (2) Favour a work climate oriented towards mutual support and good communication between various RTW stakeholders (e.g., insurer, worker, union, family physician, employer), and more specifically within the team (e.g., manager, co-workers, worker), by adopting a collaborative approach in the RTW process; (3) Demonstrate empathy and take a positive approach toward the worker’s recovery and offer support at each stage of the RTW process, considering potential detrimental effects of stigmatisation; (4) Adopt a respectful attitude toward the worker regarding confidentiality of personal information, and consequently avoid disclosing such information (e.g., details regarding the individual’s treatment or diagnosis) unless the individual has given written consent, and finally; and (5) Demonstrate openness, flexibility and creativity in offering work accommodations that facilitate the RTW since the returning worker may experience functional limitations (e.g., difficulty concentrating), either temporarily or permanently.

With respect to interactions and communication between RTW stakeholders, overall the results highlight the importance of maintaining exchanges between RTW stakeholders as well as a regular contact with the worker on sick leave. This not only ensures the continuity of workers’ recovery (e.g., needs, capacities, and limits to be respected), but also promotes the RTW process using communication channels established by stakeholders (e.g., email, telephone, in person). Regarding the RTW, various RTW stakeholders should be informed of the evolution of the treatment and of the worker’s situation. Adopting a multidisciplinary and multisector approach supported by a regular and high-quality communication between RTW stakeholders, remains the approach of choice in the literature to facilitate workers’ recovery and the RTW process.

The utilization of organization or community services and interventions is strongly encouraged to facilitate the recovery and RTW of workers on sick leave (e.g., Employee Assistance Programs, peer helper program). Authors suggest favoring EAPs over public mental health services in order to avoid long waiting lists that can have a negative impact on workers’ recovery. Specific tools validated in the domain of the RTW after a sick leave are also recommended as ways to help health professionals evaluate and monitor workers’ therapeutic interventions, particularly regarding clinical symptoms, perceived barriers to RTW and self-efficacy to overcome them, and available work accommodations. Finally, most articles suggest ensuring that the necessary training and resources (material and human) for RTW are deployed, such as training for supervisors and other workplace stakeholders (e.g., HR, unions) regarding management of workers’ RTW, prevention of relapses, warning signs detection, and the demystification of mental health problems. Continuing education and training on a regular basis (e.g., psychosocial risk factors, drug treatments) is recommended for rehabilitation professionals in order to provide workers with the best possible care.

RTW Stakeholders’ Role and Actions—Transversal Results Within a Specific System

Results also revealed roles and actions that were constant across phases, within each system (Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5). Regarding the transversal role of each stakeholder of the work system, first the worker is invited to take an active role in the RTW process, learning about symptoms (psychoeducation), building self-management skills, as well as providing information and seeking support from relevant stakeholders as needed (e.g., occupational health and safety). Second, the employer/HR, among the most documented stakeholders in the literature, should: (a) ensure the implementation in the organization of values and clear positions regarding the support offered to workers on sick leave while respecting workers’ confidentiality, (b) inform, prepare and evaluate the actions of each stakeholder in the RTW process of the worker on sick leave, and (c) focus on work accommodations and their implementation in collaboration with the manager and team. Third, the literature informs us on the manager’s role, summarized in the procedures and policies regarding the RTW, and underlines the importance to monitor and support the members of the team in regards to the worker’s sick leave. With the worker’s consent, the manager could maintain contact with the worker on sick leave, and thus maintain or reinforce his feeling of belonging to the organization. As needed, the manager could consult the designated occupational health and safety representative on questions regarding the worker’s RTW. Managers and Co-workers should encourage a climate of respect within the team and towards the colleague on sick leave (e.g., address any inappropriate or stigmatizing comments about his condition or the work accommodations granted). Fourth, with respect to co-workers in particular, key activities are clarifying the work objectives during the worker’s sick leave, and sharing issues related to work accommodations and potential psychosocial risk factors in the work environment with the manager. It is also recommended that co-workers stay in contact with the worker during the sick leave and continue to invite him to join the team’s social events and activities (i.e., Christmas party, after work get-together, recognition activities, etc.) without expectations. Fifth, union representatives should know the rules, procedures, and collective agreements related to sick leaves and RTW in order to inform, support and protect their members. The union representative could also encourage the worker to contact his occupational health and safety representative on questions regarding his sick leave.

As for stakeholders from the health system, the family physician and rehabilitation professionals should act as key resources for the other actors involved in the RTW process (e.g., insurer, employer), producing progress reports, and encouraging the worker’s involvement in the communications with other RTW stakeholders (e.g., by giving copies of the correspondence to the worker). The role of the family physician comprises four pillars: (a) Care and evaluation of the health condition of the worker on sick leave while considering the work environment; (b) Caregiver relationship by offering a secure and stable relationship attuned to the worker’s needs; (c) Consulting and teaching worker health management by suggesting appropriate interventions/services; and (d) therapeutic follow-up (e.g., gradual return to work, work accommodations). As for psychiatrist/psychologist and psychotherapists (PSY), their role is to support the worker during the sick leave and RTW while considering the actions put in place by other stakeholders stemming from diverse systems. Rehabilitation professionals often work in multidisciplinary teams and consequently should share information about the worker’s health condition (e.g., functional abilities and limitations) with professionals in other disciplines. They are essential resources for workplace stakeholders (e.g., employer and manager) and the insurance system to facilitate the worker’s RTW. Occupational physician/nurse have a specific position since they work in the organisation (a model, more often present in Europe), and consequently need to make explicit their double ‘status’ with the worker (i.e. belonging to the work system and playing the role of the healthcare provider). They adopt an orientation and values similar to other health professionals, but they are also able to more precisely identify psychosocial risk factors that may be present in the work environment (e.g., conflicts) and to work directly with the occupational health and safety team to initiate preventive interventions.

The review’s results suggest that the insurer maintains positive relationships, collaborates and exchanges information on an ongoing basis with workers, employers and health professionals involved in the workers’ medical follow-ups (e.g., family physician). The insurer’s role as described in the literature is to ensure regular contacts with the worker to prevent an eventual long-term sick leave. The insurer should consider disability criteria and associated benefits in order to determine the most relevant and cost-effective interventions for the worker on sick leave. This role highlights the power dynamic that exists between the insurer and the worker since the former has a determining influence on the worker’s financial situation and professional reintegration. The insurer should increase communication efforts with the worker’s medical team should the worker be at risk of prolonged sick leave. If necessary, the insurer can contact stakeholders outside regular insurance-delivered services for certain psychiatric assessments or rehabilitation services that may not be offered by the company.

The RTW coordinator can be attached to the workplace as well as to the insurance or health system, and therefore needs to create and maintain a working alliance with various stakeholders involved in the worker’s RTW process. The RTW coordinator is responsible for the involvement of all RTW stakeholders and is knowledgeable about rehabilitation and mental health services, organizational procedures and management values, worker’s and organization’s needs. This role should involve encouraging direct exchanges between different stakeholders in order to establish a common vision of sustainable RTW for the worker, and sometimes intervening as a mediator in cases of workplace interpersonal conflicts. The RTW coordinator should also support the other RTW stakeholders in identifying the needed resources and procedures for the worker’s RTW. Finally, the RTW coordinator monitors the evolution of worker’s health condition to reach the objective of a sustainable RTW.

All transversal roles and actions for each stakeholder are summarized in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5. Furthermore, all RTW Stakeholders’ actions are also detailed for each phase of the RTW process—Phase 1: beginning of sickness absence and involvement of disability management team; Phase 2: involvement in treatment and rehabilitation with health professionals, and preparation for RTW; and Phase 3: gradual return to work and follow up. In total, regardless of the RTW phase and system, we count from 15 to 27 recommended actions for key RTW stakeholders (i.e. worker, manager, family physician, PSY, rehabilitation professionals, occupational physician/nurse, insurer, and RTW coordinator) and less than 15 actions for others (i.e. employer, co-worker, and union representative). Interestingly, Phase 2 of the RTW seems the most detailed in terms of stakeholders’ actions (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5), and the most detailed RTW stakeholder’s actions belong to the RTW coordinator (Table 5).

Discussion

RTW for people on sick leave due to common mental disorders (CMDs) is a complex process, requiring actions from several RTW stakeholders. Several authors have criticized the scarcity of available information, specifically in regard to RTW stakeholders’ role and actions in the RTW process following workplace sickness absences due to CMDs [14, 24]. The objective of this scoping review was to document the roles and actions of RTW stakeholders involved in the RTW process of workers on sick-leave due to CMDs. Most of the screened papers (nearly 90%) came from Europe or North of America. Results of this scoping review highlighted the plethora of stakeholders involved in RTW. In total, we count eleven RTW stakeholders spread out on three systems: work, health, and insurance systems. RTW stakeholders’ roles and actions were presented according to the system to which they belong, either work, health or insurance (with the exception of the RTW coordinator, who can work in either one of these systems). These RTW stakeholders’ main roles and actions were described according to the three main phases of the RTW.

Across the results of this scoping review, we see that the active role of the worker regarding his own recovery and RTW is highlighted in all the papers screened, through regular contacts with all RTW stakeholders, more particularly with the RTW coordinator, the manager and health care providers [81, 239]. Heath care providers (e.g., general physicians), on their own, are considered advocates and gatekeepers for the worker on sick leave by providing medical opinions to determine the duration of the work absence [55, 84, 119, 162]. Health care providers—general and occupational physicians, and rehabilitation professionals—are required to communicate regularly with the insurer to determine the eligibility and duration of benefits; there is also an expectation by all these stakeholders to communicate with and advise workers who are on sick leave and their employers [153]. Interestingly, all RTW stakeholders from the health system (e.g., general physicians, rehabilitation professionals) were often mentioned in this scoping review’s results—35% to 42% of articles, depending on the specific professional, mentioned at least one of them. This scoping review offers clarification on the specific roles of each health care provider, with for instance general physicians and PSY supporting the worker’s recovery, whereas rehabilitation professionals promote quick RTW using appropriate work accommodations. General physicians assess the workers’ symptoms and functional limitations when the health condition of workers is critical, occupational physicians primarily focus on relapse prevention, always having in mind worker’s job descriptions, job demands and the availability of work accommodations [177]. Both types of physicians play an important role in facilitating the RTW of the worker on sick leave [177,255,, 250, 252].

As for employers, they are responsible for providing and establishing a supportive work climate for workers by communicating their expectations to immediate supervisors and by giving them appropriate training [79]. The employer, in consultation with the worker, is responsible for assessing the rehabilitation requirements as well as other needed health services, and for initiating measures to promote an effective rehabilitation [135]. Although there are many stakeholders in the RTW process stemming from the workplace, the manager is recognised as having a pivotal role and plays an important role in the interface between upper management, rehabilitation, and health care providers, coworkers, and the injured worker [148]. Furthermore, managers are the stakeholders who are most familiar with the requirements of the job; they are the first to communicate with workers about return to work, and they usually have the authority to implement accommodations in working conditions. Managers are in a position to facilitate workers on sick leave in their RTW process, and at the same time, to identify the accommodation measures that they could put in place to enable workers with such disabilities to perform their job [19]. However, managers tend to focus on accommodation related to strict aspects of work (e.g., schedule and tasks modification) and less on accommodation to reduce psychosocial risk factors at work (e.g. pre-existing conflicts, job strain, lack of social support, etc.), which are highly related to CMDs [266].

Several authors have mentioned that co-workers often seem invisible in the RTW process of workers on sick leave [20, 32], yet their roles and actions were described in over one third of the retained papers for this scoping review. Tujlin et al. [20] found that co-workers navigate informally through the entire RTW process, and therefore they tackle RTW issues in an ad hoc manner by trying to do what is required to ‘make it work’ for themselves and the re-entering worker, such as by offering strategic support or by re-organizing schedules. Thanks to this scoping review, we can now apprehend potential actions that they can put in place such as Participate in the redistribution of team tasks with the manager (Phase 1) and Express to the manager any concerns related to the return to work of the absent colleague and the implications on the workload (Phase 2) and thus avoid a domino effect regarding work absences in the team. Their unrecognised and invisible contribution to the eventual success of the RTW of their colleague as well as to the work climate is now better detailed in this scoping review. Even if employers do not need to formalize the roles of the co-workers in the RTW policy of the organization, a formal role with specific actions is now given to this RTW stakeholder [20, 32].

Given the high prevalence of common mental disorders in organizations, the role and involvement of union representatives have become crucial, particularly regarding their interactions in terms of negotiations with other stakeholders of the work system (e.g., employers, managers) [79]. Although scarcely mentioned in terms of rate of citations in this review (close to 11%), this scoping review allowed to clarify their roles and actions in the RTW of workers on sick leave due to CMDs. For instance, during Phase 3 of the RTW, it is suggested that follow ups with the worker be planned to ensure compliance with the terms and work conditions, particularly regarding the implementation of work accommodations [79].

Another central RTW stakeholder is the insurer, who facilitates the connection between all parties involved in the treatment and rehabilitation services [202], and has both a controlling and a supportive function [135]. Even though this RTW stakeholder is cited in only one quarter of papers, this scoping review allowed us to describe the insurer’s role and actions in great detail. For instance, almost 20 specific actions are suggested only for Phase 2, which fall in either the controlling (e.g., ensure that the work rehabilitation plan meets the criteria and the regulations of the insurance company) or the supporting function (e.g., provide support and offer advices to the worker on sick leave such as assistance with administrative procedures), as Heijbel et al. [135] suggested.

While the RTW coordinator is cited in less than 15% of reviewed articles, it is noteworthy that more than two thirds of them were published since 2010. There is a steady increase in interest around this RTW stakeholder, suggesting the coordinator’s role is critical in the RTW process. Indeed, the RTW coordinator increasingly plays a pivotal role by ensuring communication and a joint understanding of the expectations of all RTW stakeholders [267], and coordinates actions among supervisors, insurers, and healthcare providers to achieve sustainable RTW and recovery [268]. Kärkkäinen et al. [269] highlighted this central role in RTW in terms of functional (e.g., identifying RTW barriers and negotiating accommodations) and interpersonal activities (e.g., clarifying roles and liabilities of RTW stakeholders as well as collaborating). Furthermore, the RTW coordinator is not associated with a specific discipline and can therefore have different professional designations, belonging to the work, insurance or health system [203]; this lack of professional specificity may also explain why this stakeholder has only rarely been mentioned in older articles retained in this scoping review.

This scoping review aimed at providing a foundation for future studies by documenting and summarising the roles and actions of each stakeholder involved in the RTW process, in order to ultimately develop better coordination between RTW stakeholders, and better inform policy makers. Recent systematic reviews conducted on RTW workplace interventions [270] and employers’ best practice guidelines reviews [98] as well as the best evidence synthesis of systematic reviews on the environmental factors associated with positive RTW outcomes [75], all tend to identify similar and complementary components to facilitate the RTW of workers with CMDs and other types of work disability (e.g., musculoskeletal disorders). These components are: well-described organizational policies for the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders participating in the RTW process, RTW coordination, provision of health services and work modifications/work accommodations. These authors all stress the importance of better detailing these components [75,61,, 98, 270]. Knowing the roles and actions of each stakeholder, in the following paragraphs, we will try to see how these can interact and come together in the RTW of a worker with CMD.

As mentioned above, the RTW process consists of multiple interacting components supported by RTW stakeholders [271, 272] intertwined in a dynamic process [27]. As highlighted in the results of this scoping review, the choice and implementation of work accommodations are crucial, and should involve all stakeholders in a coordinated effort, particularly during Phases 2 and 3 of the RTW process. Below, we provide an illustration which demonstrates the crucial place of work accommodations in the RTW, showing how all roles and actions of RTW stakeholders are intertwined within Phases 2 and 3. As such, this illustration, in the context of selection and implementation of work accommodations to support a sustainable work resumption of the worker on sick leave due to CMDs, offers a good example of the sequential actions attached to the RTW process. Each stakeholder has a specific role to play and actions to put in place within each phase of the RTW process, particularly in Phases 2 and 3 (Phase 1 being more related to the beginning of sickness).

Phase 2: Involvement in Treatment and Rehabilitation with Health Professionals, and Preparation for RTW—Roles and Actions’ Stakeholders Regarding Work Accommodations

-

The general physician talks with the insurer or employer (e.g., via forms) to inform them of the worker’s functional limitations and ideally clarify the required work accommodations to be implemented in the workplace to meet his needs.

-

Rehabilitation professionals suggest accommodations that are suitable to the worker and the work environment (e.g., modification or reduction of work tasks, flexible work schedule). Following a significant reduction in symptoms, create a RTW plan considering residual symptoms. Highlight ability to return to work if accommodations are made in the workplace.

-

The insurer discusses the possibility of implementing work accommodations as early as the first few weeks of sick leave with the worker and the employer.

-

The employer informs managers of the potential accommodations that can be implemented in his department. In collaboration with the work team, the employer considers the particularities of the work environment of each department.

-

The RTW coordinator prepares and supports the discussion about work accommodations between the manager and worker. Analyzes the workload with the worker and manager (e.g., list the usual tasks according to the job description).

-

The worker participates in the identification of work accommodations and prioritize them considering his needs.

-

The manager evaluates with the worker and the organization’s occupational health and safety department the possibility of implementing work accommodations.

-

The union representative discusses possible work accommodations with the organization (e.g., temporary assignments) to facilitate the member’s RTW under the best possible conditions.

-

The RTW coordinator analyzes work arrangement needs and identifies those that are possible/feasible (e.g., according to the worker’s abilities and position, analyzes the cognitive abilities required at the worker’s workstation). Identifies tasks that are appropriate to the worker’s abilities. Verifies the feasibility of the implementation of the work accommodations for the worker’s RTW with the manager. Coordinates the work accommodations with the human resources, the manager and the worker (if necessary, meet/contact each stakeholder separately).

-

The manager informs the team members of the worker’s RTW process (i.e., disability extension, work accommodations, gradual RTW, regular RTW) while respecting confidentiality.

Phase 3: Gradual RTW and Follow Up—Roles and Actions’ Stakeholders Regarding Work Accommodations

-

The employer ensures the implementation and application of follow-up actions towards the worker who is returning to work by all the stakeholders involved, particularly when organizing the first day of RTW, implementing the work accommodations, and monitoring the health and productivity of the worker and the team.

-

General and occupational physicians re-evaluate the worker’s coping mechanisms and workplace accommodations to support recovery. Ensure compliance with the RTW plan and propose adjustments if necessary.

-

The PSY collaborates with the family physician, worker, employer and union representative (if applicable) to monitor the implementation of the necessary work accommodations for a sustainable RTW that promotes recovery. Makes recommendations for adjusting the RTW plan if necessary.

-

The worker applies the strategies and work accommodations that were developed/targeted in the previous phase and revises them with the relevant stakeholders when necessary.

-

The manager organizes regular follow-up meetings with the worker to evaluate the work accommodations and adjusts them if necessary. Communicates with team members regarding the evolution of the worker’s work accommodations.

-

The insurer or the RTW coordinator promotes communication between the stakeholders of the RTW, notably for the flow of the information relating to his functional limitations and the work accommodations requests.

-

The RTW coordinator monitors the RTW plan with all stakeholders involved and adjusts it according to the worker’s evolution (e.g., work accommodations). Re-evaluate the worker’s needs upon RTW (e.g., workload).

There are both strengths and limitations to this scoping review. The proposed framework includes roles and actions of key stakeholder groups belonging to three systems—work, health and insurance—and the assumption that sharing perspectives of others is useful for all RTW stakeholders. The operationalization of the roles and actions of diverse RTW stakeholders at given RTW phases should facilitate the communication between them and improve the RTW of the worker on sick leave due to CMDs. The scoping review provides a rigorous and transparent method for mapping the RTW process, offering useful information for policy makers. However, it must be noted that a scoping review’s aim is to document an area of research, and as such it does not address research questions (for instance, of efficacy) or assess the quality of retained studies, nor does it emphasizes significant over non-significant results [37]. Consequently, the roles and actions’ of RTW stakeholders in this scoping review are not necessarily related to significant results that we could eventually disentangle from a systematic review. Furthermore, roles and actions of RTW stakeholders need to be analysed according to contextual factors such as work and economic values as well as country-specific compensation policy and health systems, but also according to the different sectors of activities (e.g., private or public) where the presence of some RTW stakeholders can be optional. Also, role and actions recommended at each RTW phase, and more specifically for the worker on sick leave due to CMD, should be carefully analyzed before being implemented since the severity and scope of clinical symptoms can vary from one worker to another.

According to the type of stakeholder and the system to which they belong, the synthesis of these results could be translated differently. For example, in the workplace system, the employer, HR with the support of unions (depending on the sector of activity) could suggest organizational policies for the RTW process, and thus clarify the expectations for each RTW stakeholder’s role and actions. Furthermore, the worker could feel supported by other stakeholders since clear expectations are defined for one another (i.e. workers can feel less discriminated). From the insurance system, the insurer could translate this synthesis into preventive actions and invite other stakeholders to apply them in order to facilitate a sustainable RTW. In the health system, the research coordinator belonging to the health system could use this synthesis to create more synergy with other health professionals reflecting the role of each other, and thus avoiding a hierarchical and paternalistic structure. To conclude these stakeholders’ role and actions could eventually structure and facilitate the communication and coordination between stakeholders within the organization and more largely to other systems.

Future studies are warranted regarding the effectiveness of the roles and actions of RTW stakeholders presented in this scoping review. Moreover, the definition and operationalization of the complex roles and actions of each RTW stakeholder should be investigated, for instance by paying closer attention to specific subphases included in the three main phases of the RTW process. Consequently, we call on researchers to test a sequence of actions supported by roles of RTW stakeholders as suggested above. In this scoping review, stakeholders’ skills linked to their particular roles have not been studied, and consequently should also be targeted in future studies. To develop validated tools and training, managers and RTW coordinators’ skills should be investigated more thoroughly, as they can potentially have crucial roles to play in this area of research. For instance, studies have shown the importance of communication skills in RTW work coordinators [33, 202, 273, 274] and managers [148] in order to establish and monitor the RTW plan successfully.

Also, a better understanding of the views of different stakeholders regarding what is or is not a successful RTW would be useful. As roles and actions can lead to different work and health outcomes, future studies should use a variety of indicators to measure RTW success (e.g., sick leave duration, recurrence, job tenure, recovery) are needed [96, 275]. Finally, several studies mentioned the importance of considering actors from the community system, or at times called ‘non-work-related social networks’ of workers on sick leave due to CMDs, such as friends and family members, since they can potential influence the RTW process [31, 80, 276]. Future studies are warranted regarding the roles and actions in the RTW context of these potential RTW stakeholders. In addition to these avenues of research, there is a need for a theory-based approach in the field of work disability to better understand interactions and relations between stakeholders in regards to the RTW of workers on sick leave due to CMDs (e.g., to explain the individual, cultural, social and institutional influences of coordinated actions of the stakeholders during the RTW process). Given that this scoping review highlights the importance of principles such as sharing knowledge (e.g., stakeholders’ actions interrelated with the whole RTW process), mutual respect (e.g., respecting all stakeholders’ role and actions) and sharing goals (e.g., sustainable RTW of the worker), the relational coordination theory could be of interest to this field [277].

In conclusion, safe, sustainable, and timely RTW can be maximized through a better understanding of each stakeholder’s roles and actions. In this scoping review, eleven RTW stakeholders have been identified and spread out across the work, heath and insurance systems, from which practical roles and actions for each RTW stakeholder have emerged. Our findings add to the growing body of literature emphasizing the importance of ensuring effective communication between RTW stakeholders by establishing a common view of the roles and actions regarding RTW. We hope that this scoping review’s results will enable RTW stakeholders and policy makers to learn from each other, and eventually build practical relationships and collaboration, supported by a collective responsibility, regarding the RTW of workers on sick leave due to CMDs.

References

Claudi Jensen AG. Towards a parsimonious program theory of return to work intervention. Work Read Mass. 2013;44:155–164.

Claudi Jensen AG. A two-year follow-up on a program theory of return to work intervention. Work Read Mass. 2013;44:165–175.

Joyce S, Modini M, Christensen H, Mykletun A, Bryant R, Mitchell PB, Harvey SB. Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic meta-review. Psychol Med. 2016;46:683–697.

Netterstrom B, Friebel L, Ladegaard Y. Effects of a multidisciplinary stress treatment programme on patient return to work rate and symptom reduction: results from a randomised, wait-list controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2013;82:177–186.

Noordik E, van Dijk FJ, Nieuwenhuijsen K, van der Klink JJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an exposure-based return-to-work programme for patients on sick leave due to common mental disorders: design of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:140.

Corbière M, Negrini A, Dewa CS. Mental health problems and mental disorders: linked determinants to work participation and work functioning. In: Loisel P, Anema JR, editors. Handbook of work disability. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 267–288.

Johnsen TL, Indahl A, Baste V, Eriksen HR, Tveito TH. Protocol for the at work trial: a randomised controlled trial of a workplace intervention targeting subjective health complaints. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:844.

Norder G, Roelen CAM, van Rhenen W, Buitenhuis J, Bültmann U, Anema JR. Predictors of recurrent sickness absence due to depressive disorders—a Delphi approach involving scientists and physicians. PLoS ONE. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051792.

van Oostrom SH, Anema JR, Terluin B, de Vet HC, Knol DL, van Mechelen W. Cost-effectiveness of a workplace intervention for sick-listed employees with common mental disorders: design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:12.

Nigatu YT, Liu Y, Uppal M, McKinney S, Rao S, Gillis K, Wang J. Interventions for enhancing return to work in individuals with a common mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychol Med. 2016;46:3263–3274.

Seymour L. Common mental health problems and work: applying evidence to inform practice. Perspect Public Health. 2010;130:59–60.

Schneider U, Linder R, Verheyen F. Long-term sick leave and the impact of a graded return-to-work program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ HEPAC Health Econ Prev Care. 2016;17:629–643.

Yoshitsugu K, Kuroda Y, Hiroyama Y, Nagano N. Concise set of files for smooth return to work in employees with mental disorders. Springerplus. 2013;2:630.

Jetha A, Pransky G, Fish J, Jeffries S, Hettinger LJ. A stakeholder-based system dynamics model of return-to-work: a research protocol. J Public Health Res. 2015;4:553.

Soegaard HJ. Undetected common mental disorders in long-term sickness absence. Int J Fam Med. 2012;2012:474989.

James KG. Returning to work after experiencing mental health problems. Ment Health Pract. 2015;18:36–38.

Joosen MC, Brouwers EP, van Beurden KM, et al. An international comparison of occupational health guidelines for the management of mental disorders and stress-related psychological symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2015;72:313–322.

Dewa CS. Les coûts des troubles mentaux en milieu de travail peuvent-ils être réduits ? Santé Ment Au Qué. 2017;42:31.

Ladegaard Y, Skakon J, Elrond AF, Netterstrom B. How do line managers experience and handle the return to work of employees on sick leave due to work-related stress? A one-year follow-up study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;41(1):44–52.

Tjulin Å, MacEachen E, Ekberg K. Exploring workplace actors experiences of the social organization of return-to-work. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:311–321.

Corbière M, Lecomte T, Lachance JP, Coutu MF, Negrini A, Laberon S. Return to work strategies of employees who experienced depression: employers and human resources’ perspectives. Sante Ment Que. 2017;42:173–196.

Josephson M, Heijbel B, Voss M, Alfredsson L, Vingard E. Influence of self-reported work conditions and health on full, partial and no return to work after long-term sickness absence. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2008;34:430–437.

Nielsen MB, Bultmann U, Madsen IE, Martin M, Christensen U, Diderichsen F, Rugulies R. Health, work, and personal-related predictors of time to return to work among employees with mental health problems. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1311–1316.

Noordik E, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Varekamp I, van der Klink JJ, van Dijk FJ. Exploring the return-to-work process for workers partially returned to work and partially on long-term sick leave due to common mental disorders: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1625–1635.

Russell E, Kosny A. Communication and collaboration among return-to-work stakeholders. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;41(22):2630–2639.

Vlasveld MC, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Adèr HJ, Anema JR, Hoedeman R, van Mechelen W, Beekman ATF. Collaborative care for sick-listed workers with major depressive disorder: a randomised controlled trial from The Netherlands depression initiative aimed at return to work and depressive symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:223–230.

Young AE, Wasiak R, Roessler RT, McPherson KM, Anema JR, van Poppel MNM. Return-to-work outcomes following work disability: stakeholder motivations, interests and concerns. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15:543–556.

Hulshof C, Pransky G. The role and influence of care providers on work disability. In: Loisel P, Anema JR, editors. Handbook of work disability. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 203–215.

Loisel P. Round table with all stakeholders involved in work disability prevention. In: 3rd WDPI conference on implementing work disability prevention knowledge; 2014.

Young AE. Return to work stakeholders’ perspectives on work disability. In: Loisel P, Anema JR, editors. Handbook of work disability. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 409–423.

Loisel P, Gosselin L, Durand P, Lemaire J, Abenhaim L. Implementation of a participatory ergonomics program in the rehabilitation of workers suffering from subacute back pain. Appl Ergon. 2001;32(1):53–60.

Skivington K, Lifshen M, Mustard C. Implementing a collaborative return-to-work program: lessons from a qualitative study in a large Canadian healthcare organization. Work Read Mass. 2016;55:613–624.

Pransky G, Shaw W, Franche R, Clarke A. Disability prevention and communication among workers, physicians, employers, and insurers current models and opportunities for improvement. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:625–634.

Reynolds CA, Wagner SL, Harder HG. Physician-stakeholder collaboration in disability management: a Canadian perspective on guidelines and expectations. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:955–963.

Karrholm J, Ekholm K, Jakobsson B, Ekholm J, Bergroth A, Schuldt K. Effects on work resumption of a co-operation project in vocational rehabilitation. Systematic, multi-professional, client-centred and solution-oriented co-operation. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:457–467.

Andersen MF, Nielsen KM, Brinkmann S. Meta-synthesis of qualitative research on return to work among employees with common mental disorders. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2012;38:93–104.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Babatunde F, MacDermid J, MacIntyre N. Characteristics of therapeutic alliance in musculoskeletal physiotherapy and occupational therapy practice: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:375.

Blas AJT, Beltran KMB, Martinez PGV, Yao DPG. Enabling work: occupational therapy interventions for persons with occupational injuries and diseases: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28:201–214.

Grandpierre V, Milloy V, Sikora L, Fitzpatrick E, Thomas R, Potter B. Barriers and facilitators to cultural competence in rehabilitation services: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:23.

Reavley NJ, Ross A, Killackey EJ, Jorm AF. Development of guidelines to assist organisations to support employees returning to work after an episode of anxiety, depression or a related disorder: a Delphi consensus study with Australian professionals and consumers. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:135.

Accordino MP, McReynolds C, Accordino DB, Bard C. Professionals with psychiatric disabilities served in private disability rehabilitation: Implications for rehabilitation counselor preparation. J Appl Rehabil Couns. 2009;40:22–27.

Ahola K, Toppinen-Tanner S, Seppänen J. Interventions to alleviate burnout symptoms and to support return to work among employees with burnout: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Burn Res. 2017;4:1–11.

Akiyama T, Tsuchiya M, Igarashi Y, et al. “Rework program” in Japan: Innovative high-level rehabilitation. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2010;2:208–216.

Alexis O. The management of sickness absence in the NHS. Br J Nurs. 2011;20:1437–1442.

Andersen MF, Nielsen K, Brinkmann S. How do workers with common mental disorders experience a multidisciplinary return-to-work intervention? A qualitative study. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24:709–724.

Andren D. Does part-time sick leave help individuals with mental disorders recover lost work capacity? J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24:344–360.

Anema JR, Jettinghoff K, Houtman I, Schoemaker CG, Buijs PC, van den Berg R. Medical care of employees long-term sick listed due to mental health problems: a cohort study to describe and compare the care of the occupational physician and the general practitioner. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16:41–52.

Arends I, van der Klink JJ, van Rhenen W, de Boer MR, Bültmann U. Prevention of recurrent sickness absence among workers with common mental disorders: Results of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 2013;71(1):21–29.

Arends I, Bruinvels DJ, Rebergen DS, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Madan I, Neumeyer-Gromen A, Bultmann U, Verbeek JH. Interventions to facilitate return to work in adults with adjustment disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD006389.

Arends I, Bultmann U, Nielsen K, van Rhenen W, de Boer MR, van der Klink JJL. Process evaluation of a problem solving intervention to prevent recurrent sickness absence in workers with common mental disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2014;100:123–132.

Arends I, van der Klink JJ, Bültmann U. Prevention of recurrent sickness absence among employees with common mental disorders: design of a cluster-randomised controlled trial with cost-benefit and effectiveness evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:132.

Arends I, van der Klink JJL, van Rhenen W, de Boer MR, Bultmann U. Predictors of recurrent sickness absence among workers having returned to work after sickness absence due to common mental disorders. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40:195–202.

Bakker IM, Terluin B, van Marwijk HW, Gundy CM, Smit JH, van Mechelen W, Stalman WA. Effectiveness of a Minimal Intervention for Stress-related mental disorders with Sick leave (MISS); study protocol of a cluster randomised controlled trial in general practice [ISRCTN43779641]. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:124.

Bakker IM, Terluin B, van Marwijk HW, van der Windt DA, Rijmen F, van Mechelen W, Stalman WA. A cluster-randomised trial evaluating an intervention for patients with stress-related mental disorders and sick leave in primary care. PLoS Clin Trials. 2007;2:e26.

Baynton MA. Return-to-work: addressing co-worker reactions when mental health is a factor. OOHNA J. 2010;29:9–12.

Baynton MA. Return to work: strategies for supporting the supervisor when mental health is a factor in the employee’s return to work. OOHNA J. 2010;29:18–21.

Beyond Blue. The beyondblue National Workplace Program.pdf.

Bilsker D, Wiseman S, Gilbert M. Managing depression-related occupational disability: a pragmatic approach. Can J Psychiatry Rev. 2006;51:76–83.

Black O, Sim MR, Collie A, Smith P. Early-claim modifiable factors associated with return-to-work self-efficacy among workers injured at work: are there differences between psychological and musculoskeletal injuries? J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59:e257–e262.

Boštjančič E, Koračin N. Returning to work after suffering from burnout syndrome: perceived changes in personality, views, values, and behaviors connected with work. Psihologija. 2014;47:131–147.

Bramwell D, Sanders C, Rogers A. A case of tightrope walking: an exploration of the role of employers and managers in supporting people with long-term conditions in the workplace. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2016;9:238–250.

Brenninkmeijer V, Houtman I, Blonk R. Depressed and absent from work: predicting prolonged depressive symptomatology among employees. Occup Med Oxf Engl. 2008;58:295–301.

Briand C, Durand MJ, St-Arnaud L, Corbière M. Work and mental health: learning from return-to-work rehabilitation programs designed for workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30:444–457.

Brijnath B, Mazza D, Singh N, Kosny A, Ruseckaite R, Collie A. Mental health claims management and return to work: qualitative insights from Melbourne, Australia. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24:766–776.

Brouwers EPM, de Bruijne MC, Terluin B, Tiemens BG, Verhaak PFM. Cost-effectiveness of an activating intervention by social workers for patients with minor mental disorders on sick leave: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17:214–220.

Brouwers EPM, Tiemens BG, Terluin B, Verhaak PFM. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce sickness absence in patients with emotional distress or minor mental disorders: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:223–229.

Brouwers EPM, Terluin B, Tiemens BG, Verhaak PFM. Patients with minor mental disorders leading to sickness absence: a feasibility study for social workers’ participation in a treatment programme. Br J Soc Work. 2006;36:127–138.

Bryngelson A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Jensen I, Lundberg U, Asberg M, Nygren A. Self-reported treatment, workplace-oriented rehabilitation, change of occupation and subsequent sickness absence and disability pension among employees long-term sick-listed for psychiatric disorders: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001704.

Burton WN, Conti DJ. Depression in the workplace: the role of the corporate medical director. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:476–481.

Burton WN, Conti DJ. Disability management: corporate medical department management of employee health and productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42:1006–1012.

Cameron J, Walker C, Hart A, Sadlo G, Haslam I, Retain Support G. Supporting workers with mental health problems to retain employment: users’ experiences of a UK job retention project. Work Read Mass. 2012;42:461–471.

Cameron J, Sadlo G, Hart A, Walker C. Return-to-work support for employees with mental health problems: identifying and responding to key challenges of sick leave. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;79:275–283.

Canadian Standards Association. Psychological health and safety in the workplace. Toronto: Canadian Standards. Association; 2013.

Cancelliere C, Donovan J, Stochkendahl MJ, Biscardi M, Ammendolia C, Myburgh C, Cassidy JD. Factors affecting return to work after injury or illness: best evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Chiropr Man Ther. 2016;24:32.

Caveen M, Dewa CS, Goering P. The influence of organizational factors on return-to-work outcomes. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2006;25:121–142.

Coduti WA, Anderson C, Lui K, Lui J, Rosenthal DA, Hursh N, Ra Y-A. Psychologically healthy workplaces, disability management and employee mental health. J Vocat Rehabil. 2016;45:327–336.

Cohen D, Kinnersley P. Sickness certification and stress: reviewing the challenges. Prim Care Ment Health. 2005;3:201–204.

Corbière M, Renard M, St-Arnaud L, Coutu MF, Negrini A, Sauve G, Lecomte T. Union perceptions of factors related to the return to work of employees with depression. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25:335–347.

Corbière M, Shen J. A systematic review of psychological return-to-work interventions for people with mental health problems and/or physical injuries. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2006;25:261–288.

Corbière M, Bergeron G, Negrini A, Coutu MF, Samson E, Sauve G, Lecomte T. Employee perceptions about factors influencing their return to work after a sick-leave due to depression. J. Rehabil. 2018;84(3):3–13.

Cornelius LR, van der Klink JJ, Groothoff JW, Brouwer S. Prognostic factors of long term disability due to mental disorders: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21:259–274.

Cowls J, Galloway E. Understanding how traumatic re-enactment impacts the workplace: assisting clients’ successful return to work. Work Read Mass. 2009;33:401–411.

D’Amato A, Zijlstra F. Toward a climate for work resumption: the nonmedical determinants of return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:67–80.

Danuser B. Recovery and job retention for people with mental health problems. Rev Médicale Suisse. 2012;8:226–227.

De Bono AM. Communication between an occupational physician and other medical practitioners an audit. Occup Med. 1997;47:349–356.

de Clavière C, Kasbi-Benassouli V, Paollilo AG, Puypalat A, D’Escatha A, Pairon JC. Study of the medical and socioprofessional future of patients referred to a consultation of professional pathology for psychological suffering at work. Arch Mal Prof Environ. 2008;69:24–30.

de Vries G, Hees HL, Koeter MW, Lagerveld SE, Schene AH. Perceived impeding factors for return-to-work after long-term sickness absence due to major depressive disorder: a concept mapping approach. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85038.

de Vries G, Koeter MW, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Hees HL, Schene AH. Predictors of impaired work functioning in employees with major depression in remission. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:180–187.

de Vries G, Schene AH. Reintegration to work of people suffering from depression. In: International handbook of occupational therapy interventions. New York: Springer; 2009. p. 375–382.

de Vries H, Fishta A, Weikert B, Rodriguez Sanchez A, Wegewitz U. Determinants of sickness absence and return to work among employees with common mental disorders: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9730-1.

de Weerd BJ, van Dijk MK, van der Linden JN, Roelen CA, Verbraak MJ. The effectiveness of a convergence dialogue meeting with the employer in promoting return to work as part of the cognitive-behavioural treatment of common mental disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Work Read Mass. 2016;54:647–655.

Dell-Kuster S, Lauper S, Koehler J, Zwimpfer J, Altermatt B, Zwimpfer T, Zwimpfer L, Young J, Bucher HC, Nordmann AJ. Assessing work ability—a cross-sectional study of interrater agreement between disability claimants, treating physicians, and medical experts. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40:493–501.

Demou E, Brown J, Sanati K, Kennedy M, Murray K, Macdonald EB. A novel approach to early sickness absence management: the EASY (Early Access to Support for You) way. Work Read Mass. 2015;53:597–608.

Dewa CS, Goering P, Lin E, Paterson M. Depression-related short-term disability in an employed population. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:628–633.

Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S. Work outcomes of sickness absence related to mental disorders: a systematic literature review. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005533.

Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Joosen MCW. The effectiveness of return-to-work interventions that incorporate work-focused problem-solving skills for workers with sickness absences related to mental disorders: a systematic literature review. BMJ Open. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007122.

Dewa CS, Trojanowski L, Joosen MC, Bonato S. Employer best practice guidelines for the return to work of workers on mental disorder-related disability leave: a systematic review. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2016;61:176–185.

Dhaliwal G. Employment and disability law: implications for occupational psychiatry and employee assistance programs. Psychiatr Ann. 2006;36:758–763.

Durand M-J, Corbière M, Coutu M-F, Reinharz D, Albert V. A review of best work-absence management and return-to-work practices for workers with musculoskeletal or common mental disorders. Work Read Mass. 2014;48:579–589.

Durand M-J, Coutu M, Nastasia I, Bernier M. Pratiques des grandes organisations au Québec en regard de la coordination du retour au travail (Return-to-Work Coordination Practices of Large Organizations in Québec). Montréal: Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail; 2016.

Eguchi H, Wada K, Higuchi Y, Smith DR. Psychosocial factors and colleagues’ perceptions of return-to-work opportunities for workers with a psychiatric disorder: a Japanese population-based study. Environ Health Prev Med. 2017;22:23.

Ekberg K, Wahlin C, Persson J, Bernfort L, Oberg B. Early and late return to work after sick leave: predictors in a cohort of sick-listed individuals with common mental disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25:627–637.

Eklund M, Erlandsson LK, Wästberg BA. A longitudinal study of the working relationship and return to work: perceptions by clients and occupational therapists in primary health care service organization, utilization, and delivery of care. BMC Fam Pract. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0258-1.

Endo M, Haruyama Y, Muto T, Yuhara M, Asada K, Kato R. Recurrence of sickness absence due to depression after returning to work at a Japanese IT company. Ind Health. 2013;51:165–171.

Endo M, Muto T, Haruyama Y, Yuhara M, Sairenchi T, Kato R. Risk factors of recurrent sickness absence due to depression: a two-year cohort study among Japanese employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2014;88:75–83.

Ernstsen L, Lillefjell M. Physical functioning after occupational rehabilitation and returning to work among employees with chronic musculoskeletal pain and comorbid depressive symptoms. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:55–63.

Ervasti J, Joensuu M, Pentti J, Oksanen T, Ahola K, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M, Virtanen M. Prognostic factors for return to work after depression-related work disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:28–36.

Finnes A, Enebrink P, Sampaio F, Sorjonen K, Dahl J, Ghaderi A, Nager A, Feldman I. Cost-effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy and a workplace intervention for employees on sickness absence due to mental disorders. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59:1211–1220.

Flach PA, Groothoff JW, Krol B, Bultmann U. Factors associated with first return to work and sick leave durations in workers with common mental disorders. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22:440–445.

Flach PA, Krol B, Groothoff JW. Determinants of sick-leave duration: a tool for managers? Scand J Public Health. 2008;36:713–719.

Fleten N, Johnsen R. Reducing sick leave by minimal postal intervention: a randomised, controlled intervention study. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:676–682.

Foley M, Thorley K, Van Hout MC. Assessing fitness for work: GPs judgment making. Eur J Gen Pract. 2013;19:230–236.

Frank AO, Thurgood J. Vocational rehabilitation in the UK: opportunities for health-care professionals. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2006;13:126–134.

Freeman D, Cromwell C, Aarenau D, Hazelton M, Lapointe M. Factors leading to successful workplace integration of employees who have experienced mental illness. Empl Assist Q. 2004;19:51–58.

Friesen MN, Yassi A, Cooper J. Return-to-work: the importance of human interactions and organizational structures. Work. 2001;17(1):11–22.

Gabbay M, Taylor L, Sheppard L, Hillage J, Bambra C, Ford F, Preece R, Taske N, Kelly MP. NICE guidance on long-term sickness and incapacity. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e118–e124.

Gilbert M, Samra J. Guarding minds @ work: a workplace guide to psychological safety and health. Canadian Benefits & Compensation Digest; 2010. p. 10–12.

Gjesdal S, Holmaas TH, Monstad K, Hetlevik O. GP consultations for common mental disorders and subsequent sickness certification: register-based study of the employed population in Norway. Fam Pract. 2016;33:656–662.

Glozier N, Hough C, Henderson M, Holland-Elliott K. Attitudes of nursing staff towards co-workers returning from psychiatric and physical illnesses. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2006;52:525–534.

Gouin MM, Coutu MF, Durand MJ. Return-to-work success despite conflicts: an exploration of decision-making during a work rehabilitation program. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;41(5):523–533.

Grossi G, Santell B. Quasi-experimental evaluation of a stress management programme for female county and municipal employees on long-term sick leave due to work-related psychological complaints. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:632–638.

Hansen A, Edlund C, Branholm IB. Significant resources needed for return to work after sick leave. Work Read Mass. 2005;25:231–240.

Hara KW, Bjorngaard JH, Brage S, Borchgrevink PC, Halsteinli V, Stiles TC, Johnsen R, Woodhouse A. Randomized controlled trial of adding telephone follow-up to an occupational rehabilitation program to increase work participation. J Occup Rehabil. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9711-4.

Harder HG, Hawley J, Stewart A. Disability management approach to job accommodation for mental health disability. In: Work accommodation and retention in mental health. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 425–441.

Harvey S, Henderson M. Occupational psychiatry. Psychiatry. 2009;8:174–178.

Harvey S, Williams S. Management of depression in NHS staff: results of the first national clinical audit. Occup Health (Lond). 2009;61:29–30.

Haugli L, Maeland S, Magnussen LH. What facilitates return to work? Patients’ experiences 3 years after occupational rehabilitation. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21:573–581.

Haukka E, Martimo KP, Kivekas T, et al. Efficacy of temporary work modifications on disability related to musculoskeletal pain or depressive symptoms—study protocol for a controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008300.

Haveraaen LA, Skarpaas LS, Berg JE, Aas RW. Do psychological job demands, decision control and social support predict return to work three months after a return-to-work (RTW) programme? The rapid-RTW cohort study. Work J Prev Assess Rehabil. 2016;53:61–71.

Hayashi K, Taira Y, Maeda T, Matsuda Y, Kato Y, Hashi K, Kuroki N, Katsuragawa S. What inhibits working women with mental disorders from returning to their workplace?—a study of systematic re-employment support in a medical institution. Biopsychosoc Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-016-0080-6.