Abstract

Purpose The purpose of this study was to explore how employers and co-workers experience the return to work (RTW) process of employees undergoing cancer treatment. Methods Sixteen semi-structured individual interviews and participant observations at seven workplaces took place, involving seven employers and nine co-workers with different professions. A phenomenological-hermeneutic analytic approach was applied involving coding, identification of themes, and interpretation. Results We identified three employer themes: call for knowledge, Making decisions, and Feeling helpless. Also, three co-worker themes were identified: understanding and sympathy, extra work and burden, and Insecurity about future work tasks. Early initiated RTW, e.g. less work hours and work accommodations, did neither constitute challenges for employers nor co-workers in the beginning of the RTW process. However, when the RTW process was prolonged employers encountered difficulties in finding suitable work tasks, whereas co-workers were burdened by extra work. Conclusions Overall, cancer survivors’ RTW process was welcomed and encouraged at the workplace level. However, employer and co-worker experiences suggested that RTW initiation parallel with cancer treatment raised challenges at the workplace level, when the RTW process was extended beyond the initial RTW plan; increased workload and difficulties in balancing the needs of the cancer survivor and co-workers. Mechanisms that support cancer survivors’ RTW without introducing strain on co-workers should be investigated in future research. Furthermore, support for employers in their RTW management responsibilities needs to be addressed in general and in particular in future RTW interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Employees undergoing cancer treatment experience difficulties returning to work, and many risk recurrent sickness absence and permanent exclusion from the labor market [1, 2]. A meta-analysis has found that employees undergoing cancer treatment are 1.37 times more likely to be unemployed than healthy controls [3]. Employees emphasize the importance of retaining the ability to work, also while being treated for cancer [4]. Although research on the return to work (RTW) process for employees undergoing cancer treatment is growing [3], only few studies have explored how employers experience the RTW process [5, 6]. Multiple factors seem to influence employers’ management of employees diagnosed and treated for cancer [7]. Employer-perceived barriers and facilitators seem related to support, communication, RTW policies, knowledge about cancer, balancing interests and roles, and attitudes [6]. Evidence on how employer management and support of employees undergoing cancer treatment impacts on the employees’ ability to RTW is scant. Moreover, to our knowledge, no studies have explored how co-workers may be affected during the RTW process of employees undergoing cancer treatment. To understand how employers and co-workers view the process of regaining work participation of colleagues undergoing cancer treatment the framework of International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), and concepts about work participation from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines of rehabilitation were used [8, 9]. According to the ICF model, environmental factors may hamper or facilitate work participation [8]; this viewpoint was explored from the perspective of employers’ and co-workers’ and how they perceived external factors in the RTW process with a colleague undergoing cancer treatment.

Background

Former qualitative studies show that employers find it demanding to manage the RTW process [6, 7]. Managers tend to have negative attitudes regarding the ability of employees undergoing cancer treatment to engage in work and meet employment demands [10]. A review found that employer-employee relationship may constitute barriers to collaboration during the RTW process, as communication seems to be difficult [11]. The RTW process is demanding due to various dilemmas, despite shared goal of successful RTW between employers and employees [12]. Employers’ willingness to provide support seems to be shaped by a positive pre-cancer perception of the employee, shared employer and employee goals, and national or organizational policies supporting the employer in managing the RTW process [6]. Legislation on RTW is primarily aimed at the sick-listed. Furthermore, employers require more knowledge in order to support employees undergoing cancer treatment in the RTW process, as management courses do not provide such health-related aspects [6].

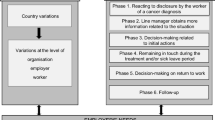

The Danish Sickness Benefit Act applies to everyone on sick leave [13]. It makes municipal job centers responsible for providing occupational rehabilitation services to sickness beneficiaries, and the maximum period a sick-listed employee can receive sickness benefit payments was reduced from 52 to 26 weeks in 2014. Occupational rehabilitation services during cancer treatment are not standard municipal procedures, and hospitals devote even less attention to occupational rehabilitation [14]. Employers are responsible for paying wages to sick-listed employees in the first 30 days of a sick leave spell. If the sick leave period exceeds 30 days, the employer will be reimbursed by the state as from day 30 and until the employee returns to work, the employment contract ends voluntarily or involuntarily, or the maximum sickness benefit period (26 weeks) ends or cannot be prolonged. Hence, in a legal sense, employers’ financial responsibility for the RTW process applies only to the first 30 days of a sick leave spell where they have to bear the cost of the employee’s absence. The municipalities are not obliged to service employers if they express particular needs in the RTW process. In Denmark, RTW is a collaborative effort where municipal social workers in the job centers support employees in returning to work. These social workers reach out to workplaces, informing the employers of the social workers’ responsibility, available occupational rehabilitation services and give employers contact information. The present study was conducted within the framework of the Danish Sickness Benefit Act as well as the RTW intervention aimed at employees undergoing cancer treatment [15]. The intervention was adjusted and tailored according to the employees’ individual needs, resources, and readiness for RTW, by two municipal social workers responsible for the occupational rehabilitation offered. Employers were invited to contact the two social workers if they had any questions or concerns about the RTW process of their sick-listed employee enrolled in the RTW intervention. The employees participated in the intervention for a maximum of one year. The intervention was deliberately initiated as early as possible and parallel with the cancer treatment to allow the social workers to discuss and start the RTW planning during the employee’s treatment. Typically, employees undergoing cancer treatment are exempted from the obligatory municipal initiatives while undergoing treatment. However, this exemption also shortens the time frame in which occupational rehabilitation may take place after treatment completion and the sickness benefit expiry. One of the aims of the RTW intervention was to challenge this procedure and allow for a thorough and realistic RTW plan of the sick-listed employee at the workplace. The individualized plan would typically involve part-time work schemes and changes in work tasks to test the employee’s work ability in the initial RTW phase [15].

Former studies have found the RTW process of employees after long-term sick leave is not only influenced by the work accomodations made by employers but also by co-workers’ behavior [16, 17]. Work accomodations may affect employees’ ability to RTW as well as co-workers’ ability to be supportive [10]. Employees undergoing cancer treatment encounter several challenges in returning to and maintaining work, which calls for a concerted effort especially during the recovery process [18]. How to address these issues at the workplace seems to be a challenge for employers, line managers and direct supervisors, and this call for further investigation of how the RTW process is experienced during a RTW intervention study. The aim of the present study was therefore to explore how employers and co-workers experienced the RTW process of employees undergoing cancer treatment.

Methods

We applied an explorative qualitative research design undertaking semi-structured individual interviews and participant observation at seven workplaces where an employee undergoing cancer treatment was enrolled in the RTW intervention study; trial registration ISRCTN50753764 (15).

Inclusion Criteria

Included in this study were employers functioning as direct supervisors of day-to day work tasks, and co-workers at the workplace who were in close teamwork with the colleague returning to work.

Recruitment Procedure

The sick-listed employees undergoing cancer treatment were asked by the social workers at the municipal job centers if they would allow the first author to contact their workplace and their direct supervisors. The employees who were undergoing cancer treatment had been gradually returning to work with less demanding work tasks and less work hours for about 2 till 3 months at the time of the recruitment. After giving informed consent to the recruitment of their direct supervisor and close co-workers, the direct supervisor were contacted by telephone by the first author and asked whether they would participate in the current study.

Participants and Work Settings

We conducted 16 individual interviews with 13 females and 3 males aged 38–57 years. The participants were employed in seven different workplaces: two shops, one school, one kindergarten, one activity center, one hospital, and one municipal service department (Table 1). The work tasks were primarily service-oriented tasks; sales, service delivery, health care, childcare, and teaching. During the workday, the employees were in direct contact with several people, e.g. customers, patients, clients, and children. The co-workers in the team were dependent on the colleague returning to work and this person’s work ability in order to solve their own work tasks.

Individual Interviews

From September 2015 to December 2016, 16 individual interviews were carried out (KSP) at seven workplaces involving seven employers and nine co-workers. Participants were informed about the background and purpose of the interview. A semi-structured interview guide with open and thematic questions was used. Questions were focusing on the employers’ experiences of the challenges involved in the RTW management, and on the co-workers’ perceptions of the RTW process and experiences of the challenges in the close teamwork with the returning colleague (Table 2). Follow-up questions were used to gain deeper insight into their personal experiences: “Can you tell me more about…”; “You mentioned … will you elaborate on…”; “I would like to understand how it has been to… can you tell me more”; “What did you think about …”. Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim, and names and places were erased to ensure that participants remained anonymous.

Participant Observation

Participant observations (KSP) including informal conversations took place at the seven workplaces in agreement with the employee undergoing cancer treatment. The purpose was to gain insight into the work site context to which the employee returned. The strategy during observations was to obtain an open and trustful dialogue with employers and co-workers to encourage people to talk about their work in order to get insight into how work tasks were shared among the workers in the team. The observations were performed in order to gain insight into the work performed at the workplaces, the work tasks and the co-workers’ assignments related to the employee’s RTW process. Observations took place while the employee was present at the workplace and they lasted for 2–3 h. Information on how work was performed and the work tasks involved gathered from these observations was used to understand the nature of the work tasks and the interaction of the employee undergoing cancer treatment with the employer (direct supervisor) and co-workers. Field notes were made shortly after these observations. This was followed by a more comprehensive description of what people said and did during observations and the interactions observed while performing work tasks. Participant observations e.g., specific work situations could be referred to and thereby enlighten questions and answers in the individual interviews.

Analysis

A phenomenological-hermeneutic approach to the analysis was applied (KSP). The approach involved two analytic steps performed by (KSP). The first step was content analysis with open coding and inductive theme identification [19]. The second step was interpretation of the identified themes of importance in light of the theories applied [20].

- Step 1:

-

Content analysis involved open coding and theme identification based on the transcribed interviews [19, 21, 22]. Themes were refined through several coding rounds until a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ experiences was obtained. The identified themes and subthemes were presented in the research team. Field notes were openly coded in order to describe and understand the settings in which the participants worked and interacted with the employees undergoing cancer treatment during the RTW process. Table 3 present the identified themes with excerpts of the most illustrative quotes

Table 3 Identified themes and subthemes on workplace actors’ perspectives

- Step 2:

-

The identified themes from step 1 were interpreted using theories and concepts from a theoretical framework with a view to moving the analysis from a description of the participants’ subjective and individual experiences to a more theoretical understanding of the overall meaning of their statements [20]. The interpretation was qualified by use of a modified model of the ICF developed by Heerkens et al. [23]. The model addresses occupational rehabilitation and focuses on the interplay between the health of the employee and the environmental factors. Thus, the ICF framework was used as a lens through which employers and coworkers were seen, and how they view the role of environmental factors, and what they perceive as barriers and facilitators

Results

The results of the analysis revealed three themes illustrating the employers' perspectives on how they experienced the RTW process of employees undergoing cancer treatment. The employers’ challenges related to the RTW process were centered on: Call for knowledge, Making decisions, and Feeling helpless. Another three themes from the co-workers` perspectives on how they experienced the RTW process of the colleague returning were identified: Understanding and sympathy, Extra work and burden, and Insecurity about future work tasks (Table 3).

Employers’ Perspective

A recurring theme voiced by employer was inadequate knowledge of how to manage the RTW process. Even though the employers did have contact with social workers at the municipal job centers as part of the RTW intervention study, they experienced that contact with job centers in general did not support the management of the RTW process of sick-listed employees. When asked about their contact with the municipal social workers responsible for the employee’s RTW, the employers emphasized that the RTW plan was drawn up by the social workers in collaboration with the employee undergoing cancer treatment with a view to meet their needs, not theirs as employers. The employers’ responsibility was to plan and manage the team’s work tasks, which gave rise to frustration. The direct supervisor talked in person with the employee about the RTW plan. At larger workplaces a human resource officer performed this talk. The RTW plans encompassed reduced work hours and modified work tasks, which affected co-workers’ work schedules and work tasks.

Direct supervisors with day-to-day managerial responsibility for appointing work tasks to the team of employees at the workplace found it challenging to decide on different organization of work tasks during the period of gradual RTW. Although the RTW plan was discussed and agreed upon at the meeting with the employer, an employee undergoing cancer treatment and a social worker, it became even more challenging to put the plan into practice when the RTW process dragged on. The employers involved in the round table meetings were not always the ones who were responsible for the day-to-day work tasks. To be able to organize the work, the direct supervisors had to assess the day-to-day work ability of the employee and be able to judge when they could increase the work hours. They found it challenging to find an appropriate way to ask the employee undergoing cancer treatment to resume usual work tasks and work hours.

The majority of the direct supervisors mentioned that overall sick leave rates were rather high at their workplaces and that they had employees currently absent for other reasons than because of cancer, and this was an extra burden on the workplace. Managing yet another employee on long-term sick leave and gradually reintegrating that employee made the direct supervisors frustrated. In the beginning of the RTW process, they felt confident about being able to manage it. However, as time went by, they found it more difficult to keep on managing the reduced work hours and modified work tasks without knowing when this would end. The direct supervisors were empathic and understood that employees undergoing cancer treatment could not manage a full-time work schedule in the beginning of the RTW process. At some workplaces, temporary workers were hired to compensate for the reduced work hours of the part time sick-listed employees. However, such compensation did not always fulfill the needs, especially at workplaces with few employees who were very dependent on each other.

Co-workers’ Perspective

A recurring theme voiced by co-workers was sympathy and understanding as to why the colleague returning to work had to start gradually and why work tasks had to be modified. Co-workers all expressed this understanding in the beginning of the RTW process. Some had family and friends who have had cancer, and this personal experience lay at the root of their willingness to adjust their work routines to help in the beginning of the RTW process.

The co-workers all emphasized that the absence of their colleague affected their work, as they had to take over some of their colleague’s usual duties. Overall, the co-workers had neither been involved in the RTW plan nor informed about its consequences for them; and they were accordingly surprised by the amount of extra work they ended up doing despite the use of temporary workers. Only those co-workers who were close friends with the colleague returning to work and met privately were informed about the RTW plans by their colleague. In these cases, the colleague returning to work disclosed the challenges they encountered in this process while still recovering; and that seemed to make it easier for co-workers to accept the consequences. The use of temporary workers never fully compensated for the partial absence of the colleague. The modified work tasks appointed to the colleagues returning affected the closest co-workers the most, and they felt a higher workload than more distant co-workers.

The extra work appointed to the co-workers was experienced as an extra burden, and some co-workers said that they were not sure how long they could manage. Echoing the employers’ experiences, the co-workers expressed uncertainty about how long they could manage to keep up with the extra work demands. When the RTW plan was too optimistic, and the RTW process seemed to have no defined endpoint, the co-workers became unsure about how and if their colleague would ever be able to resume his or her usual work tasks. That represented a dilemma because they would like to be the understanding close-by co-worker, and on the other hand they expressed uncertainty about the future work situation and wanted to be able to foresee when they could resume their usual work tasks without the extra demands.

Discussion

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore how employers and co-workers experienced the RTW process of an employee at the workplace, while this person was undergoing cancer treatment. At seven workplaces 16 semi-structured individual interviews and participant observations took place, and data was analysed by use of a phenomenological-hermeneutic approach. A mutual perspective from both employers’ and co-workers’ on gradual RTW with fewer work hours and less demanding work tasks were not a problem in the first phase of the RTW process. However, a longer RTW process caused different perspectives; namely increased workload for co-workers and difficulties in balancing the needs within the team from the direct supervisors’ point of view. Thus, similarities and differences found across the included workplaces gave insight into positive and negative aspects of the RTW process of a sick listed employee undergoing cancer treatment. All good intentions expressed by direct supervisors and co-workers were difficult to follow because of the uncertain duration of the RTW process.

A large variety of perceived employer-related barriers and facilitators for work participation of employees undergoing cancer treatment have been identified in previous studies and related to both willingness and ability to offer support [6,7,8]. In contrast to the studies included in the review by Greidanus et al. [6], the responsibility for initiating occupational rehabilitation in the present study lays with stakeholders outside the workplace. What may seem as a disadvantage from a company perspective is counterbalanced by low costs related to sickness absence for the employer, as the municipality and state reimburses the majority of these costs. However, imbalance may be introduced when structural incentives, which encourage early RTW such as sickness benefit schemes being less generous, are introduced [24]. The RTW intervention study by Stapelfeldt et al. [13] aimed to meet employees’ wish to RTW while recovering from their cancer disease and treatment [14], while at the same time adapt the intervention within the current Danish Sickness Benefit Act [9]. That meant an early onset of municipal social worker-initiated occupational rehabilitation and thereby an early contact between the employees undergoing cancer treatment and their employers.

This constitutes a challenge for many employers who want to ensure that their employees are effective and perform their work assignments efficiently. Thus, it supports the rationale for employees staying away from work until full recovery is obtained [14]. This rationale is questioned primarily by the social security system and to some extent employees undergoing cancer treatment. In the present study the employers expressed concerns about the social workers, who mainly catered for the employee’s interests and to further their sustainable RTW. Whereas the early onset of RTW did not adequately address the employer’s responsibility for the co-workers’ work environment [6].

According to the WHO, rehabilitation of people with disabilities is a process aiming to enable people to reach and maintain their optimal level of physical, sensory, intellectual, psychological, and social functioning [23]. It aims to give persons the tools needed to attain independence and self-determination. In a biopsychosocial understanding, work is a means for participating in meaningful activities, assuming that the body (physically and mentally) is capable of functioning despite possible side effects and late effects from cancer treatment. The themes identified in the present study showed how employers strived to implement the RTW plan initiated by the municipal stakeholder in cooperation with the employee undergoing cancer treatment, as an integrated part of rehabilitation. The biopsychosocial understanding embedded in ICF insists on a holistic understanding of rehabilitation, which calls for considerations related to the individual’s rehabilitation needs in general and in particular to issues related to work participation and work environment when occupational rehabilitation is the focus. These issues are expressed in the expanded version of the ICF according to Heerkens et al. [23]. Though Stapelfeldt et al. [13] address the need to involve stakeholders in the RTW process; the needs voiced by employers in the present study seemed not to be catered for. And the hypothesized employer-experienced barriers stemming from unprepared and poor RTW plans were not overcome by the early social worker-initiated RTW intervention.

Involving workplace actors more explicitly in the rehabilitation efforts is not commonly used in Denmark, there is no Danish system of occupational health services. Thus, primarily healthcare professionals are responsible for and provide rehabilitation [9]. In the RTW intervention study by Stapelfeldt et al., social workers from the municipal job centers did collaborate with the employers [13]. Still, the intervention was tailored to target the particular needs of the employees undergoing cancer treatment. This was in conformity with the Danish Sickness Benefit Act, which stipulates that municipal job centers are not legally obliged to support employers and co-workers while providing occupational rehabilitation to sick-listed employees [11]. Even so, the Danish municipalities may inform employers about their services and invite them to contact them with questions and possible mutual efforts to support their employees’ RTW. In most cases, the social worker contacts the employer to arrange round table meetings for discussion of RTW plans.

The identified challenges perceived by the participants in the present study show that the RTW process of employees undergoing cancer treatment introduce several dilemmas, which calls for a discussion of how best to involve the workplace. Further investigation of workplace actors’ needs during the RTW process could help qualify future RTW interventions targeting not only the employee undergoing cancer treatment but also employers and co-workers in other work settings. The provision of workplace support and RTW plans for work modifications during cancer treatment has shown to facilitate positive RTW outcomes and to enable cancer patients to remain at work [25,26,27,28]. In the present study, the employers were all implementing a gradual RTW plan, which they perceived would facilitate sustainable RTW even if the protracted process had negative workplace implications. Identifying those at risk of encountering difficulties in the RTW process could help qualify occupational rehabilitation efforts and awareness of modifiable factors [27]. In the present study, the employees investigated worked in occupations in the low-income and medium-income groups. Unfavorable work conditions typical of low-income and low-level educational jobs are viewed as possible factors explaining inequality in RTW [29]. The present study supports this; moreover, we found that efforts made by the employers to accommodate the employees’ RTW needs caused a non-desirable work environment for their co-workers, possibly increasing co-workers’ risk of being sick-listed due to the extra workload.

The two ICF models offer a systematic description of functions, activities, and participation, which can describe how the individual’s functioning may influence on work participation, and how contextual factors may influence the RTW process [8, 23]. Work-related factors such as terms of employment, social relationships at work, tasks, and working conditions are examples of external factors that influence the individual’s work participation. The present study focused on how the workplace factors, shaped the workplace actors’ perspective on the RTW process. Reintegrating an employee during cancer treatment is demanding for employers, and current legislation does not necessarily offer the support needed [10]. Leadership and communication training could help support employers in the process of reintegrating employees and help improve their communication skills [30].

Strengths and Limitations

This qualitative study included workplaces with a majority of female employees with team-based work tasks. Gender differences may exist in relation to the RTW process, therefore the study findings should be transferred to other work settings only with caution. Results from a Swedish register study found that high educational level and high income is associated with a higher probability of an early RTW [31]. The choice of workplaces was made after consulting social workers and participants enrolled in the individually tailored RTW intervention [13]. This may have influenced the study findings, as strategic sampling was not possible. Hence, due to unknown reasons for non-participation it is unclear whether our findings can be transferred to comparable work settings. Furthermore, the preliminary findings were discussed with the social worker involved; this helped contextualize the findings and gave insight into the possible implications of the RTW intervention on workplace factors.

The interviews were inspired by a semi-structured guide, which may have limited the variety of perspectives among the participants. However, as the interviews were individual we believe that the perspectives were less censored than if the participants were interviewed in focus-groups. Thus, the present study provided insight into employer and co-worker perspectives on the RTW process among employees undergoing cancer treatment, and highlighted challenges when initiating early RTW. Previous studies conducted within this field were in settings influenced by either insurance-based benefit systems or occupational health services [6, 9, 10]. Whereas the present study findings are influenced by a tax-financed benefit system, in which the employers’ responsibilities are limited. Despite the contextual differences our findings confirm existing knowledge.

Conclusions

Overall, cancer survivors’ RTW process was welcomed and encouraged at the workplace level. However, employer and co-worker experiences suggested that RTW initiation parallel with cancer treatment raised challenges at the workplace level when the RTW process was extended beyond the initial RTW plan; namely increased workload for co-workers and difficulties in balancing the needs of the employee undergoing cancer treatment and co-workers from the direct supervisors’ point of view. Mechanisms that support employees’ RTW without introducing strain on co-workers should be investigated in future research. Furthermore, support for employers in their RTW management responsibilities needs to be addressed in general and in particular in future RTW interventions.

References

Carlsen K, Dalton SO, Diderichsen F, Johansen C. Risk for unemployment of cancer survivors: a Danish cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1866–1874.

Carlsen K, Harling H, Pedersen J, Christensen KB, Osler M. The transition between work, sickness absence and pension in a cohort of Danish colorectal cancer survivors. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002259. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002259.

de Boer AGEM, Taskila T, Ojajärvi A, van Dijk FJH, Verbeek JHAM. Cancer survivors and unemployment. A meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA. 2009;301:753–762.

Loisel P, Anema JR. Handbook of work disability. In: Loisel P, Anema JR, editors. Prevention and management. Berlin: Springer; 2013.

Amir Z, Wynn P, Chan F, Strauser D, Whitaker S, Luker K. Return to work after cancer in the UK: attitudes and experiences of line managers. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:435–442.

Greidanus M, Boer A, Rijk A, Tiedtke C, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Frings-Dresen M, et al. Perceived employer-related barriers and facilitators for work participation of cancer survivors: a systematic review of employers’ and survivors’ perspectives. Psycho-Oncology. 2018;27:725–733.

Amir Z, Popa A, Tamminga S, Yagil D, Munir F, de Boer A. Employer’s management of employees affected by cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:681–684.

Escorpizo R, Finger ME, Glässel A, Gradinger F, Lückenkemper M, Cieza A. A review of functioning in vocational rehabilitation using The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21:134–146.

World Health Organization. World Report on Disability 2011. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; 2011.

Amir Z, Wynn P, Chan F, Strauser D, Whitaker S, Luker K. Return to work after cancer in the UK: attitudes and experiences of line managers. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:435–442.

Tiedtke C, de Rijk A, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Christiaens MR, Donceel P. Experiences and concerns about ‘returning to work’ for women breast cancer survivors: a literature review. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19:677–683.

Tiedtke CM, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Frings-Dresen MHW, De Boer AGEM, Greidanus MA, Tamminga SJ, Rijk AE. Employers’ experience of employees with cancer: trajectories of complex communication. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:562–577.

The Danish Benefit Act (Serviceloven) In: Retsinformation. https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/r0710.aspx?id=197036. Accessed 17 July 2018.

Petersen KS, Momsen AH, Stapelfeldt CM, Olsen P, Nielsen CV. Return-to-work intervention parallel with cancer treatment—providers’ experiences and challenges. Eur J Cancer Care. 2017;27:e12793. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014746.

Stapelfeldt CM, Labriola M, Jensen AB, Andersen NT, Momsen AH, Nielsen CV. Municipal return to work management in cancer survivors undergoing cancer treatment: a protocol on a controlled intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:720–731.

MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche RL, et al. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:257–269.

Tjulin A, MacEachen E, Stiwne EE, et al. The social interaction of return to work explored from co-workers experiences. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1979–1989.

Stergio-Kita M, Pritlove C, van Eerd D, Holness LD, Kirsh B, Duncan A, et al. The provision of workplace accomondations following cancer: survivor, provider and employer perspectives. J Cancer Patientship. 2016;10:489–504.

Schreier M. Qualitative content analysis in practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2012.

Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2014.

Hsiu-Fang H, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288.

Cresswell JW. Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2003.

Heerkens Y, Engels J, Kuiper C, Van der Guiden J, Oostendorp R. The use of ICF to describe work related factors influencing the health of employees. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;2(26):1060–1066.

Petersen KS, Labriola M, Nielsen CV, Ladekjær E. Work reintegration after long-term sick-leave: work conditions affecting co-workers ability to be supportive. A qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:1872–1883.

Mehnert A, de Boer A, Feuerstein M. Employment challenges for cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;1:2151–2159.

Lindbohm ML, Kuosma E, Taskila T, Hietanen P, Carlsen K, Gudbergsson S, et al. Cancer as the cause of changes in work situation (a NOCWO study). Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:805–812.

Kiasuwa RM, Otter R, Mortelmans K, Arbynn M, Van Oyen H, Bouland C, et al. Barriers and opportunities for return-to-work of cancer patients: time for action—rapid review and expert consultation. Syst Rev. 2016;24:35–45.

Murphy K, Nguyen V, Shin K, Sebastian-Deutch A, Frieden L. Health care professionals and the employment-related needs of cancer patients. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27:296–305.

Amir Z, Brocky J. Cancer patientship and employment: epidemiology. Occup Med (Lond). 2009;59:373–377.

Brown RF, Owens M, Bradley C. Employee to employer communication skills: balancing cancer treatment and employment. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:426–433.

Leijon O, Josephson M, Osterlund N. Sick-listing adherence: a register study of 1.4 million episodes of sickness benefit 2010-2013 in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2015;14:380–395.

Author Contributions

The data collection and analysis was independently carried out by KSP. All authors were engaged in designing the study, writing the manuscript, and discussing the findings. Furthermore, the authors and social workers were discussing the preliminary findings; this helped contextualize the findings and gave insight into the possible implications of the RTW intervention on workplace actors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and the funding bodies had no impact on the study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. The cancer survivor gave their consent to contact the direct supervisors and co-workers. Informed written consent was obtained from all persons who were interviewed and their anonymity was guaranteed. The study was registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency (Record No. 1.16-02-657-14).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Petersen, K.S., Momsen, A.H., Stapelfeldt, C.M. et al. Reintegrating Employees Undergoing Cancer Treatment into the Workplace: A Qualitative Study of Employer and Co-worker Perspectives. J Occup Rehabil 29, 764–772 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09838-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09838-1