Abstract

The incidence of proximal early gastric cancer (EGC) is increasing, and while laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy (LPG) has been performed as a surgical option, it is not yet the standard treatment, because there is no established common reconstruction method following proximal gastrectomy (PG). We reviewed the English-language literature to clarify the current status and problems associated with LPG in treating proximal EGC. This procedure is considered indicated for EGC located in the upper third of the stomach with clinical T1N0, but not when it can be treated endoscopically. No operative mortality or conversion to open surgery was reported in our review, suggesting that this procedure is technically feasible. The most frequent postoperative complication involved problems with anastomoses, possibly caused by the technical complexity of the reconstruction. Although various reconstruction methods following open PG (OPG) and LPG have been reported, there is no standard reconstruction method. Well-designed multicenter, randomized, controlled, prospective trials to evaluate the various reconstruction methods are necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The incidence of proximal early gastric cancer (EGC) is increasing, especially in Japan and Korea, because of advances in diagnostic procedures and mass screening programs [1–3]. To treat proximal EGC, proximal gastrectomy (PG) has been widely accepted in Asian countries, because it offers the same oncological survival as total gastrectomy (TG) [4], but leaves the patient with better ability to eat [5–7]. Conversely, in Western countries, TG has been performed routinely for proximal EGC and for advanced cardio-esophageal cancer [4]. Thus, whether PG or TG is the better choice for the treatment of proximal EGC remains controversial.

Since laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) for EGC localized in a distal portion of the stomach was first performed by Kitano et al. in 1991 in Japan [8], laparoscopic procedures for EGC have gained acceptance because of their advantages over conventional open surgery, including less invasiveness and pain, earlier recovery, and better cosmetic results [9–12]. As laparoscopic techniques have progressed, the indications for laparoscopic gastrectomy have expanded to the treatment of proximal EGC and distal advanced gastric cancer [10, 13–15]. Interestingly, several new types of laparoscopic PG (LPG) and TG have been developed for the treatment of proximal EGC, but LPG is not yet universally accepted [9, 11].

We review the reports published in the English-language literature on LPG for proximal EGC to clarify the current status of this procedure and its problems from the viewpoints of technical feasibility and postoperative patient quality of life (QOL), including factors, such as dietary habits and nutritional status.

Transition from open PG to laparoscopic PG

Open PG (OPG) has been widely performed for proximal EGC to improve the patient’s ability to eat after gastrectomy, especially in Japan [16, 17]. However, the evaluation of OPG has been controversial, especially in terms of its indications, extent of lymph node dissection, and best reconstruction methods to use.

The Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2010 (version 3) approved OPG for the treatment of proximal EGC. The indication for OPG is proximal EGC with T1N0 [18]. These guidelines also recommend that the volume of remnant stomach should be more than half the size of the stomach after OPG to ensure eating is not compromised greatly after gastrectomy. Thus, the important points relating to the indications for OPG are not only tumor size, but also the volume of the remnant stomach.

In terms of the extent of lymph node dissection, the above guidelines recommend D1 (LN stations 1, 2, 3a, 4sa, 4sb, and 7) or D1+ (D1 + 8a, 9, and 11p) lymph node dissection for proximal EGC. Dissection of the D1 or D1+ lymph nodes is selected according to the cancer depth, size, and histology of the EGC. It remains debatable whether the vagus nerve is dissected during dissection of the nos. 1 and 3a lymph nodes in OPG.

The method of reconstruction used after OPG is one of the most important issues and remains a concern, because the type of reconstruction contributes largely to the better ability to eat after OPG. There are three representative methods of reconstruction after OPG: esophagogastrostomy (EG) (Fig. 1a), jejunal interposition (JI) (Fig. 1b), and double-tract reconstruction (DTR) (Fig. 1c). Several new reconstruction methods after OPG, such as Kamikawa’s esophagogastric anastomosis procedure in Japan, have recently been developed to prevent reflux after OPG for EGC [19]. However, a standard reconstruction method has not yet been established.

In 1999, Kitano et al. transformed OPG to a laparoscopic procedure with minimal invasiveness [20]. Presently, several laparoscopic surgeons have developed a number of new LPG procedures based on experience gained from OPG and laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. For LPG to be accepted worldwide, it is necessary to investigate the present status of LPG and to clarify the technical and oncological problems associated with the procedure.

Present status of LPG in Japan

The incidence of EGC in Asian countries, especially Japan and Korea, is higher than that in Western countries. This has led to the development of minimally invasive treatments, including endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and laparoscopic surgery in Japan. A national survey conducted by the Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery (JSES) revealed that about 2800 patients with gastric cancer underwent LPG during the period from 1994 to 2013 (Fig. 2) [22]. In 2013, LPG accounted for approximately 4.6 % (n = 425) of all laparoscopic operations for gastric cancer in Japan, and the number of LPGs performed (n = 353) was greater than that of OPG. Thus, although sufficient clinical evidence of the superiority of laparoscopic surgery for proximal EGC over that of open surgery has yet to be established, LPG has evolved with certainty in Japan.

from [17] with permission

Laparoscopic surgery for gastric cancer. LATG laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy, LAPG laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy, LADG laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy, LWR laparoscopic wedge resection, IGMR intragastric mucosal resection

Indications for LPG (Table 1)

In the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2010 (version 3), OPG is classified as modified surgery for the treatment of proximal EGC for which endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or ESD is not indicated because of the risk of lymph node metastasis (n1) or technical difficulty.

Although the indication for LPG is considered to be the same as that for OPG, the following two important evaluations before surgery are necessary before LPG can be chosen. First, it is important to evaluate tumor location preoperatively to ensure the volume of remnant stomach represents more than half the full size of stomach after PG. Takeuchi et al. reported that the indication for LPG is EGC with a tumor diameter of less than 4 cm in the upper third of the stomach (Table 1) [23]. Ahn et al. reported that when the tumor size was relatively large, the volume of remnant stomach was too small to perform EG and to gain some functional benefit from LPG, and in such cases, they performed laparoscopy-assisted TG [24]. Kim et al. reported that the oral margin of all lesions undergoing LPG should be located within less than 3–4 cm from the esophagogastric junction [25]. When performing LPG, the tumor location is important to ensure that there is sufficient volume of remnant stomach.

Second, the preoperative evaluation of the risk of lymph node metastasis is also important. According to a previous retrospective report, the incidence of lymph node metastasis for EGC in the upper third of the stomach is not high [26], and the frequency of lymph node metastasis is very low at lymph node station nos. 3b, 4d, 5, 6, or 12 in patients with proximal mucosal or submucosal cancer [27–30]. The Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2010 (version 3) recommends D1 (LN stations 1, 2, 3a, 4sa, 4sb, and 7) or D1+ (D1 + 8a, 9, and 11p) LN dissection for proximal EGC. Takeuchi et al. analyzed the location of identified sentinel nodes in all 37 patients who underwent LPG [23]. They did not identify sentinel nodes at station nos. 5, 6, 10, or 11d in patients who had cT1N0M0 gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach diagnosed preoperatively. Based on these data, D1 or D1+ lymph node dissection is thought to be adequate in LPG for proximal EGC [31]. Therefore, the appropriate indication for LPG is considered to be EGC in the upper third of the stomach, securing sufficient volume of remnant stomach, a clinical TNM stage of T1N0 (stage IA), and no indication for EMR or ESD because of technical difficulty. The Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines drawn up by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association also proposed that clinical stage T1N0 can be an indication for PG. According to the JSES survey on the indications for LPG, LPG was indicated for 29 % of mucosal cancers, 31 % of submucosal cancers within 500 μm, 35 % of submucosal cancers over 500 μm, and only 8 % of invasion through the muscularis propria [22].

Reconstruction methods after LPG (Table 2)

The reconstruction method used after OPG is crucial for preventing the two major complications of this operation: gastroesophageal reflux and anastomotic stenosis. The three most popular reconstruction methods used after OPG are EG, JI, and DTR (Table 2). The EG procedure is considered a simple reconstruction method, because it requires only one anastomosis; however, this method is associated with a potential increase in postoperative reflux esophagitis, and anastomotic stenosis. The JI procedure has been shown to prevent severe gastroesophageal reflux; however, it requires three anastomoses, making it technically complex. In addition, abdominal fullness and discomfort can occur postoperatively in patients undergoing JI because of delayed emptying caused by the disruption of food passage in the interposed segment. Thus, numerous methods of reconstruction after OPG have been developed [32], with attempts made to apply them to LPG. Ultimately, reconstruction after LPG is still associated with difficulty and immaturity, and a convenient and reliable method needs to be developed.

LPG with EG reconstruction has been performed using a circular or linear stapler with the addition of an anti-reflux system. Aihara et al. reported that LPG with gastric tube reconstruction using a circular stapler was simple and safe, but the incidence of anastomotic stenosis was much higher (35 %) than in other reports [33]. Yasuda et al. reported a modified EG reconstruction with a reliable His angle created by placing a gastric tube in LPG [34]. This procedure had advantages over the JI technique because of its simplicity and low incidence of gastroesophageal reflux. Hiki et al. reported that they performed esophageal-to-anterior gastric wall anastomosis using a laparoscopic double-stapling technique without the need to apply a purse-string suture [35]. Recently, the circular stapler was used with the OrVil™ (Coviden, Mansfield, MA, USA) system for EG in laparoscopic surgery. The OrVil™ system was developed for transoral delivery of the anvil head. Takeuchi et al. [23] performed esophagogastric anastomosis using the OrVil™ system in LPG and reported easy and secure anastomotic reconstruction. Jung et al. [36] and Hirahara et al. [37] applied these procedures to esophagojejunostomy during LPG. EG reconstruction using a linear stapler in LPG was first reported by Uyama et al. [38] and described as a simpler and more convenient method [39, 40]. Okabe et al. reported performing LPG with a hand-sewn esophagogastric anastomosis using a knifeless linear stapler in ten patients [41].

Although various methods of JI reconstruction after LPG have been developed, this method has not yet gained acceptance because of its technical complexities and its requirement for a greater number of anastomoses. Moreover, the mean surgical time is longer than for other procedures. Uyama et al. first reported performing complete LPG with JI reconstruction in four patients, and the mean operative time was long (614 min) [42]. However, Kinoshita et al. subsequently reported that their median operation time for LPG with JI reconstruction was 233 min, although it was still longer than that for open surgery (201 min) [21]. Ahn et al. found that LPG with DTR for proximal EGC had a lower incidence of postoperative reflux symptoms (4.6 %) among 43 patients [43]. Nomura et al. studied functional outcomes affected by the reconstruction technique following LPG and prospectively compared them after the DTR and JI reconstruction methods [44]. They noted that the DTR method might be considered suitable for patients with impaired glucose tolerance.

Some other reconstruction methods after LPG have been designed especially to prevent esophageal reflux. Sakuramoto et al. wrapped the residual stomach around two-thirds of the circumference of the esophagus, similar to a Toupet fundoplication, achieving a low incidence of postoperative clinical symptoms, such as heart burn (15 %) [39]. Kim et al. reported performing laparoscopic cardia-preserving PG for EGC located more than 4 cm below the esophagogastric junction [45]. Kim et al. reported lower esophageal sphincter-preserving LPG in patients with EGC [25]. Although these studies had only a small number of patients, the procedures described were considered to be technically feasible and safe.

Simple and safe reconstruction methods following LPG must be developed to adequately prevent gastroesophageal reflux and anastomotic stenosis.

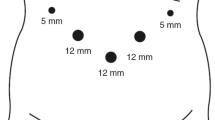

Technical feasibility of LPG (Table 2)

The technical feasibility of LPG is evaluated in terms of operative findings, such as the operation time and blood loss, and intra- and postoperative complications [46].

In nine reports pertaining to the outcome of LPG, the mean operation time for LPG ranged from 180 to 330 min (Table 2), and the mean blood loss ranged from 20 to 236 ml. Only one retrospective study has compared the operative findings of LPG with those of OPG [21]. In that study, the operation time was about 30 min longer for LPG than for OPG, but the blood loss with LPG was much less than that with OPG (20 vs. 242 ml). LPG is associated with longer operation times and less blood loss than OPG, just as LADG is. There have been three studies comparing the operative findings of LPG with those of laparoscopic TG [24, 40, 47]. Two of these studies found that LPG had shorter operative times and lower estimated blood loss than laparoscopic TG [24, 47].

The safety of LPG is evaluated in terms of mortality and morbidity. According to the JSES survey, the rate of conversion from a laparoscopic procedure to an open procedure in PG was only 1.5 %. The incidences of intraoperative and postoperative complications associated with LPG were 1.4 and 19.7 %, respectively. The most common postoperative complication was anastomotic stenosis (6.5 %) [22]. No operative mortality or conversion to open surgery found in our review (Table 2). The rate of postoperative early complications associated with LPG ranged from 7 to 35 %. There was no significant difference in the incidence of postoperative early complications between LPG and OPG or laparoscopic TG. Kinoshita et al. compared the short-term surgical variables and outcomes between LPG with JI reconstruction vs. OPG with JI reconstruction [21]. They found no differences in safety or curability between the two groups, but the laparoscopic group had significantly less postoperative pain than the open group. These results suggest that LPG is safe for patients with proximal EGC. After LPG, the most common postoperative early complications relate to anastomotic problems, such as stenosis and leakage. This high incidence may be a reflection of the technical complexity of the reconstruction.

Patient QOL after LPG (Table 3)

Some patients who undergo OPG may suffer heartburn or abdominal fullness caused by gastroesophageal reflux or gastric stasis [48–51]. These symptoms could lead to poor patient QOL after surgery and are thought to be caused by the following several disorders of the remnant stomach after OPG.

-

1.

Loss of gastric peristalsis caused by resection of the autonomic nerve systems and the pacemaker, which is responsible for the peristalsis generated by the gastric smooth muscles.

-

2.

Loss of the anti-reflux system, such as the lower esophageal sphincter.

-

3.

Functional imbalance between the food reservoir capacity and discharge capacity in the remnant stomach.

Patient QOL after LPG is evaluated in terms of postoperative late complications and loss of body weight. According to our review, the most common postoperative late complications were anastomotic stenosis and reflux esophagitis (Table 3). Several reconstruction methods after LPG have been developed to prevent anastomotic stenosis and reflux esophagitis.

The frequency of anastomotic stenosis after LPG ranged from 0 to 35 %, averaging about 13 % in ten studies. It is commonly considered that the rate of anastomotic stenosis is higher in patients who undergo reconstruction using a circular stapler than in those who undergo reconstruction using a linear stapler. None of the reports we reviewed documented this complication (Table 3). However, both Hosogi et al. [52] and Aihara et al. [33] reported high rates of anastomotic stenosis, of 20 and 35 %, respectively, for LPG followed by gastric tube reconstruction using a circular stapler. These results indicate that LPG followed by gastric tube reconstruction with a circular stapler might be associated with anastomotic stenosis after surgery.

Another common postoperative complication after LPG is reflux esophagitis. The severity and frequency of reflux esophagitis appear to be related to the reconstruction method used rather than to the type of resection performed [53]. Various reconstruction methods for the anti-reflux system, such as the narrow gastric tube procedure, the Toupet-like fundoplication procedure, and esophagojejunostomy, have been developed. According to the previous reports on reflux esophagitis after OPG, the symptoms were not associated with endoscopic findings [50, 54, 55]. In our review, the frequency of both reflux esophagitis symptoms and endoscopic findings after LPG ranged from 0 to 32 % and 0 to 29 %, respectively (Table 3). In seven of these ten studies, the endoscopic findings of reflux esophagitis were associated with the symptoms of reflux esophagitis. The high frequency of symptoms or endoscopic findings of reflux esophagitis were associated with esophagogastrectomy with gastric tube reconstruction. However, Ichikawa et al. reported no symptoms related to reflux esophagitis in EG using a circular stapler in LPG via a left abdominal incision [56]. They demonstrated through a manometric study that the lower esophageal sphincter was preserved for a length of 4 cm from the esophagogastric junction. In their comparison of LPG with laparoscopic TG, Ahn et al. reported that the incidence of reflux symptoms was significantly higher in the LPG group (32 %) than in the laparoscopic TG group (3.7 %) [24]. However, they could not conclude that LPG was a good alternative to laparoscopic TG. Other studies found no difference in the incidence of reflux symptoms after surgery between LPG and laparoscopic TG [40].

Patient QOL after gastrectomy is mainly affected by loss of body weight; thought to be strong indicator of nutritional status [43]. There are many causes of weight loss after gastrectomy, including loss of appetite, insubstantial oral intake, alternation of intestinal flora, and increased peristalsis and diarrhea [57, 58]. We reviewed a few reports of the effects of LPG on body weight loss, which stated that the mean percent body weight loss after LPG was about 10 % of the preoperative weight. Ahn et al. reported that the mean weight loss at 6 months after LPG with the DTR procedure was 5.9 %, whereas that after TG was 16 % [43]. No other reports compared body weight loss after LPG with that after laparoscopic TG.

In Japan, OPG is recognized as a function-preserving procedure for the treatment of EGC located in the upper third of the stomach. Pyloric function, which prevents gastric stasis and duodenogastric reflux, is preserved even after OPG and may be affected by the preservation of the autonomic nerve system. Ahn et al. [43] and Ichikawa et al. [56] reported that the hepatic and pyloric branches of the vagus nerves were routinely preserved in LPG without pyloroplasty. Kinoshita et al. reported that the vagus nerves were preserved on a case-by-case basis in LPG without pyloroplasty [21]. The role that complete or incomplete preservation of the autonomic nerve system plays in pyloric function in PG is still unclear, and there are very few clinical reports on pyloric function of the remnant stomach after LPG. Ahn et al. reported performing a routine gastric emptying scan to evaluate gastric stasis and duodenogastric reflux and found that gastric emptying was delayed to some extent, and the rate of food residue was 48.9 % in postoperative endoscopy [43]. We need to establish the best reconstruction method following LPG, from the viewpoint of preserving the function of the remnant stomach. Further detailed investigations, such as a health-related QOL questionnaire, analysis of gastric remnant peristalsis, and pre- and postoperative 24-h pH monitoring, are necessary.

Conclusion

LPG has developed consistently as a minimally invasive surgical option for EGC located in the upper third of the stomach. Various reconstruction methods following LPG have been developed, and these procedures appear to be oncologically and technically feasible. However, the optimal reconstruction method after LPG is still under debate from the viewpoints of improved the function of the remnant stomach, the nutritional state of the patient, and QOL after surgery. Well-designed multicenter, randomized, controlled, prospective trials are necessary to establish a standard reconstruction method after LPG.

References

Ahn HS, Lee HJ, Yoo MW, Jeong SH, Park DJ, Kim HH, et al. Changes in clinicopathological features and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer over a 20-year period. Br J Surg. 2011;98:255–60.

Jeong O, Park Y-K. Clinicopathological features and surgical treatment of gastric cancer in South Korea: the results of 2009 nationwide survey on surgically treated gastric cancer patients. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11:69–77.

Sano T, Hollowood K. Early gastric cancer: diagnosis and less invasive treatments. Scand J Surg. 2006;95:249–55.

Wen L, Chen XZ, Wu B, Chen XL, Wang L, Yang K, et al. Total vs. proximal gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:633–40.

Adachi Y, Inoue T, Hagino Y, Shiraishi N, Shimoda K, Kitano S. Surgical results of proximal gastrectomy for early-stage gastric cancer: jejunal interposition and gastric tube reconstruction. Gastric Cancer. 1999;2:40–5.

Takeshita K, Saito N, Saeki I, Honda T, Tani M, Kando F, et al. Proximal gastrectomy and jejunal pouch interposition for the treatment of early cancer in the upper third of the stomach: surgical techniques and evaluation of postoperative function. Surgery. 1997;121:278–86.

Kameyama J, Ishida H, Yasaku Y, Suzuki A, Kuzu H, Tsukamoto M. Proximal gastrectomy reconstructed by interposition of a jejunal pouch. Surgical technique. Eur J Surg. 1993;159:491–3.

Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146–8.

Tanimura S, Higashino M, Fukunaga Y, Takemura M, Tanaka Y, Fujiwara Y, et al. Laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: experience with more than 600 cases. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1177–81.

Shiraishi N, Yasuda K, Kitano S. Laparoscopic gastrectomy with lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:167–76.

Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N, Japanese Laparoscopic Surgery Study Group. A multi-center study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245:68–72.

Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, et al. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248:721–7.

Cai J, Wei D, Gao CF, Zhang CS, Zhang H, Zhao T. A prospective randomized study comparing open versus laparoscopy-assisted D2 radical gastrectomy in advanced gastric cancer. Dig Surg. 2011;28:331–7.

Hu Y, Ying M, Huang C, Wei H, Jiang Z, Peng X, et al. Oncologic outcomes of laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a large-scale multicenter retrospective cohort study from China. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2048–56.

Fang C, Hua J, Li J, Zhen J, Wang F, Zhao Q, et al. Comparison of long-term results between laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy and open gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2014;208:391–6.

Harrison LE, Karpeh MS, Brennan MF. Total gastrectomy is not necessary for proximal gastric cancer. Surgery. 1998;123:127–30.

Katai H, Sano T, Fukagawa T, Shinohara H, Sasako M. Prospective study of proximal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Br J Surg. 2003;90:850–3.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–23.

Kamikawa Y, Kobayashi T, Kamiyama, Satomoto K. A new procedure of esophagogastrostomy to prevent reflux following proximal gastrectomy. Shoukakigeka. 2001;24:1053–60 (in Japanese).

Kitano S, Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Suematsu T, Bando T. Laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy for early gastric carcinomas. Surg Today. 1999;29:389–91.

Kinoshita T, Gotohda N, Kato Y, Takahashi S, Konishi M, Kinoshita T. Laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for gastric cancer in the proximal third of the stomach: a retrospective comparison with open surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:146–53.

Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery. Nationwide survey on endoscopic surgery in Japan. J Jpn Soc Endosc Surg. 2014;5:535–40 (in Japanese).

Takeuchi H, Oyama T, Kamiya S, Nakamura R, Takahashi T, Wada N, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy with sentinel node mapping for early gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2011;35:2463–71.

Ahn SH, Lee JH, do Park J, Kim HH. Comparative study of clinical outcomes between laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy (LAPG) and laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) for proximal gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:282–9.

Kim DJ, Lee JH, Kim W. Lower esophageal sphincter-preserving laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy in patients with early gastric cancer: a method for the prevention of reflux esophagitis. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:440–4.

Kurihara N, Kubota T, Otani Y, Ohgami M, Kumai K, Sugiura H, et al. Lymph node metastasis of early gastric cancer with submucosal invasion. Br J Surg. 1998;85:835–9.

Kwon SJ. Prognostic impact of splenectomy on gastric cancer: results of the Korean Gastric Cancer Study Group. World J Surg. 1997;21:837–44.

Kitamura K, Yamaguchi T, Nishida S, Yamamoto K, Ichikawa D, Okamoto K, et al. The operative indications for proximal gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Surg Today. 1997;27:993–8.

Monig SP, Collet PH, Baldus SE, Schmackpfeffer K, Schroder W, Thiele J, et al. Splenectomy in proximal gastric cancer: frequency of lymph node metastasis to the splenic hilus. J Surg Oncol. 2001;76:89–92.

Shin SH, Jung H, Choi SH, An JY, Choi MG, Noh JH, et al. Clinical significance of splenic hilar lymph node metastasis in proximal gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1304–9.

Sano T, Aiko T. New Japanese classifications and treatment guidelines for gastric cancer: revision concepts and major revised points. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:97–100.

Nakamura M, Yamaue H. Reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy for gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach: a review of the literature published from 2000 to 2014. Surg Today. 2016;46:517–27.

Aihara R, Mochiki E, Ohno T, Yanai M, Toyomasu Y, Ogata K, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy with gastric tube reconstruction for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2343–8.

Yasuda A, Yasuda T, Imamoto H, Kato H, Nishiki K, Iwama M, et al. A newly modified esophagogastrostomy with a reliable angle of His by placing a gastric tube in the lower mediastinum in laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2014 (Epub ahead of print).

Hiki N, Fukunaga T, Yamaguchi T, Nunobe S, Tokunaga M, Ohyama S, et al. Laparoscopic esophagogastric circular stapled anastomosis: a modified technique to protect the esophagus. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:181–6.

Jung YJ, Kim DJ, Lee JH, Kim W. Safety of intracorporeal circular stapling esophagojejunostomy using trans-orally inserted anvil (OrVil) following laparoscopic total or proximal gastrectomy—comparison with extracorporeal anastomosis. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:209.

Hirahara N, Monma H, Shimojo Y, Matsubara T, Hyakudomi R, Yano S, et al. Reconstruction of the esophagojejunostomy by double stapling method using EEA OrVil in laparoscopic total gastrectomy and proximal gastrectomy. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:55.

Uyama I, Sugioka A, Matsui H, Fujita J, Komori Y, Hatakawa Y, et al. Laparoscopic side-to-side esophagogastrostomy using a linear stapler after proximal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:98–102.

Sakuramoto S, Yamashita K, Kikuchi S, Futawatari N, Katada N, Moriya H, et al. Clinical experience of laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy with toupet-like partial fundoplication in early gastric cancer for preventing reflux esophagitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:344–51.

Tsujimoto H, Uyama I, Yaguchi Y, Kumano I, Takahata R, Matsumoto Y, et al. Outcome of overlap anastomosis using a linear stapler after laparoscopic total and proximal gastrectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:833–40.

Okabe H, Obama K, Tanaka E, Tsunoda S, Akagami M, Sakai Y. Laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with a hand-sewn esophago-gastric anastomosis using a knifeless endoscopic linear stapler. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:268–74.

Uyama I, Sugioka A, Fujita J, Komori Y, Matsui H, Hasumi A. Completely laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition and lymphadenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:114–9.

Ahn SH, Jung do H, Son SY, Lee CM, Park do J, Kim HH. Laparoscopic double-tract proximal gastrectomy for proximal early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:562–70.

Nomura E, Lee SW, Kawai M, Yamazaki M, Nabeshima K, Nakamura K, et al. Functional outcomes by reconstruction technique following laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: double tract versus jejunal interposition. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:20.

Kim J, Kim S, Min YD. Consideration of cardia preserving proximal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer of upper body for prevention of gastroesophageal reflux disease and stenosis of anastomosis site. J Gastric Cancer. 2012;12:187–93.

Katayama H, Kurokawa Y, Nakamura K, Ito H, Kanemitsu Y, Masuda N, et al. Extended Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Japan Clinical Oncology Group postoperative complications criteria. Surg Today. 2016;46:668–85.

Tanimura S, Higashino M, Fukunaga Y, Kishida S, Ogata A, Fujiwara Y, et al. Laparoscopic gastrectomy with regional lymph node dissection for upper gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2007;94:204–7.

An JY, Youn HG, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Kim S. The difficult choice between total and proximal gastrectomy in proximal early gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2008;196:587–91.

Yoo CH, Sohn BH, Han WK, Pae WK. Long-term results of proximal and total gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma of the upper third of the stomach. Cancer Res Treat. 2004;36:50–5.

Katai H, Morita S, Saka M, Taniguchi H, Fukagawa T. Long-term outcome after proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for suspected early cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Br J Surg. 2010;97:558–62.

An JY, Youn HG, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Kim S. The difficult choice between total and proximal gastrectomy in proximal early gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2008;196:587–91.

Hosogi H, Yoshimura F, Yamaura T, Satoh S, Uyama I, Kanaya S. Esophagogastric tube reconstruction with stapled pseudo-fornix in laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy: a novel technique proposed for Siewert type II tumors. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2014;399:517–23.

Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Kitano S, Kakisako K, Inomata M, Yasuda K. Clinical outcome of proximal versus total gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2002;26:1150–4.

Shiraishi N, Hirose R, Morimoto A, Kawano K, Adachi Y, Kitano S. Gastric tube reconstruction prevented esophageal reflux after proximal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:78–9.

Iwata T, Kurita N, Ikemoto T, Nishioka M, Andoh T, Shimada M. Evaluation of reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy: prospective comparative study of jejunal interposition and jejunal pouch interposition. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:301–3.

Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Okamoto K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Esophagogastrostomy using a circular stapler in laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy with an incision in the left abdomen. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:57–62.

Braga M, Zuliani W, Foppa L, Di Carlo V, Cristallo M. Food intake and nutritional status after total gastrectomy: results of a nutritional follow-up. Br J Surg. 1988;75:477–80.

Bergh C, Sjostedt S, Hellers G, Zandian M, Sodersten P. Meal size, satiety and cholecystokinin in gastrectomized humans. Physiol Behav. 2003;78:143–7.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Noriko Ando for kindly drawing detailed figures of the surgical procedures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ueda, Y., Shiroshita, H., Etoh, T. et al. Laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Surg Today 47, 538–547 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-016-1401-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-016-1401-x