Abstract

Purpose

To estimate the feasibility and limitations of incomplete cytoreductive surgery and modern systemic chemotherapy in patients with synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer and to identify risk factors for death and factors associated with the patient prognosis.

Methods

Sixty-five consecutive patients underwent surgery for synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer at Hiroshima University, Japan between 1992 and 2012. The clinical, histological, and survival data were analyzed for independent risk factors and prognostic factors. The patients were retrospectively stratified into two groups according to the extent of surgery: complete cytoreductive surgery or incomplete cytoreductive surgery.

Results

The median survival times in the complete and incomplete cytoreductive surgery groups were 29.8 and 10.0 months, respectively. Receiving systemic chemotherapy alone was an independent risk factor for death in the incomplete cytoreductive surgery group (P < 0.001). Oxaliplatin and molecular-targeted drug (cetuximab or bevacizumab) therapies were also independent prognostic factors (P < 0.001), whereas irinotecan therapy was not a prognostic factor (P = 0.494).

Conclusion

Oxaliplatin and molecular-targeted drug therapies improved the overall survival in patients undergoing incomplete cytoreductive surgery. Future trials for patients with synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer should be undertaken, with patients stratified according to treatment with complete cytoreductive surgery or incomplete cytoreductive surgery with modern chemotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer (CRPC) is present in 5 % of patients at the first diagnosis of a primary colorectal tumor [1]. CRPC is considered to be a terminal condition [median survival time (MST): 5.2–12.6 months] [2–4], with patients treated with palliative intent, and surgery only recommended to palliate complications, such as intestinal obstruction [2, 3]. Recently, a randomized trial showed that patients with CRPC treated with cytoreductive surgery (CRS) plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) and systemic chemotherapy had a better prognosis than patients who received only systemic chemotherapy [4, 5].

However, this treatment has not been universally adopted for three main reasons. First, the target treatment group in that study was limited to patients with isolated and resectable peritoneal carcinomatosis, with no disease progression after 2–3 months of neoadjuvant chemotherapy [5]. Second, the treatment regimen was associated with a high rate of complications (23–53 %) [4, 6–8]. Third, the subdivisions of the patients with CRPC were limited; the only independent factor for predicting a cure in patients receiving complete CRS (CCRS) followed by intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy was a peritoneal cancer index (PCI) [9] ≤10 [10]. Despite these disadvantages, this novel systemic chemotherapy regimen also improved the overall survival (OS) in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in recent studies [11–14].

Data focused on the outcomes of surgical procedures for CRPC followed by systemic chemotherapy are limited [15, 16]. The specific aims of the present study were to determine the risk factors and outcomes of synchronous CRPC in colorectal cancer patients and to provide a comprehensive overview of the epidemiological, histopathological, and clinical features of two groups of patients; those who underwent CCRS and those who underwent incomplete CRS (ICCRS). Through a comprehensive data analysis, we have defined the risk and prognostic factors that are correlated with the CCRS and ICCRS groups, and provide new insight into synchronous CRPC that may refine the current treatment strategy.

Patients and methods

Historical cohort description

All patients with synchronous CRPC treated at Hiroshima University between September 1992 and December 2012 were included in this study. These patients were selected paraoperatively according to the following criteria: surgically and histologically proven synchronous CRPC, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status <2. Patients with metachronous CRPC, appendiceal carcinoma or peritoneal pseudomyxoma were excluded.

CCRS and ICCRS

All patients were considered to have undergone either curative or noncurative operations based on the preoperative abdominal computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging and/or positron emission tomography–CT results. The suitability of curative or noncurative surgery for each patient was based on a consensus reached at preoperative meetings.

The presence of peritoneal carcinomatosis was diagnosed at the time of the operation and was confirmed by a pathological analysis. All patients included in this study received a final diagnosis of CRPC at the time of the operation for colorectal cancer and underwent surgical intervention for CRPC.

Complete cytoreductive surgery was performed in all cases with a preoperative diagnosis of the possibility of a curative operation to remove all visible intraperitoneal tumor deposits (R0 resection, completeness of cytoreduction (CCR) score CCR0 [8]), the primary colorectal tumor (including D2 systemic mesenteric lymph node dissection) and other metastases (including liver, ovarian, or uterine metastases), except in cases with gross peritoneal or lung metastases. Patients with four or fewer liver metastases and with liver metastases not exceeding 5 cm underwent the resection of liver metastasis in addition to resection of the primary colorectal cancer and peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Incomplete cytoreductive surgery was performed in cases that were not eligible for CCRS due to the presence of unresectable extraperitoneal disease not amenable to R0 resection, as determined by consensus at the preoperative meetings.

Systemic chemotherapy

Decisions regarding chemotherapy regimens were made on an individual patient basis by medical oncologists. In the beginning of this study period, treatment with 5-fluorouracil and folic acid or irinotecan was the standard palliative treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer in Japan. From 2005 onward, oxaliplatin was incorporated into the standard palliative treatment regimen. Targeted therapies, such as bevacizumab and cetuximab, were gradually introduced in Japan in 2007, and have been added to the chemotherapy combination therapies ever since.

Postoperative follow-up

Patients who underwent surgery for CRPC had follow-up appointments every 3 months during the first 2 years, every 6 months over the next 3 years and yearly thereafter. A physical examination and serum carcinoembryonic antigen and/or carbohydrate antigen 19.9 measurements were performed, and systemic CT was performed at each visit. The follow-up data were recorded in a prospective database.

Statistical analysis

We studied both the baseline patient parameters [age, sex, primary tumor site, tumor (T) stage, lymph node (N) stage, tumor differentiation, evidence of microscopic venous and lymphatic vessel invasion, treatment (systemic chemotherapy and/or surgery) and the presence of extraperitoneal metastasis] and postoperative data [postoperative complications, early postoperative death (within 30 days of surgery) and deaths during the follow-up period and their causes].

The data were analyzed with the statistical software package SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 19, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The clinical and histological parameters of the two groups were compared using Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data, and with the Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Cox proportional hazard modeling (Cox regression) was used to determine the predictors for the assessment of risk factors or prognostic factors for patients with CRPC, CCRS, and ICCRS. The multivariate analysis used a backward, stepwise logistic regression model, including all variables with P < 0.1 in the univariate analysis. The results of the univariate and multivariate analyses are presented as odds ratios with 95 % confidence intervals. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared using the log-rank test.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between September 1992 and December 2012, 65 patients with synchronous CRPC underwent surgical intervention at our institution. The patient characteristics and clinical data are summarized in Table 1. The patient cohort consisted of 37 males and 28 females, with a median age of 64 years (range, 17–83 years). The 5-year OS rate and MST were 7.5 % and 11.9 months, respectively. Low-grade postoperative complications occurred in eight patients; seven patients experienced wound infections and one patient had ileus. There were no 30-day mortalities. The results of the univariate analysis are listed in Table 2. The univariate analysis indicated that pN > 2, ICCRS, the extent of metastatic disease, and no systemic chemotherapy were associated with a high risk of death, while a multivariate analysis found that pN > 2, ICCRS and no systemic chemotherapy were independent risk factors (Table 2).

CCRS and ICCRS patient groups

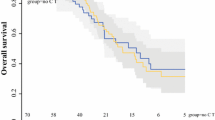

The 65 patients with synchronous CRPC were divided into two groups: a CCRS group and an ICCRS group. Significant differences were found between the CCRS and ICCRS groups with regard to the pT stage and extent of metastatic disease (P < 0.01). An analysis of survival determined that the 2- and 5-year OS rates and MST were significantly better in the CCRS group than in the ICCRS group (56.3, 22.5 %, and 29.8 months vs 22.7, 0 %, and 10.0 months, respectively; P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The median follow-up times in the CCRS and ICCRS groups were 29.8 and 8.9 months, respectively.

Risk and prognostic factors

A univariate analysis indicated that pN > 2 and the extent of metastatic disease were associated with a higher risk of death in the CCRS group (Table 3). A multivariate analysis of the CCRS group determined that pN > 2 was the only independent risk factor (hazard ratio, 15; 95 % confidence interval, 2.3–99.8; P = 0.005). A univariate analysis of the ICCRS group determined that systemic chemotherapy was the only prognostic factor. Treatment with new chemotherapeutic agents, such as oxaliplatin, cetuximab, and bevacizumab, was associated with a good prognosis (Table 3). An analysis of survival according to the use of systemic chemotherapy showed that the OS was significantly better in patients receiving oxaliplatin, cetuximab, or bevacizumab than in patients receiving no systemic chemotherapy (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer is frequently discovered unexpectedly during surgery for primary colorectal cancer, and CRPC is not detected preoperatively in 91 % of cases [17]. This presents a challenge to the operating surgeon with regard to choosing the appropriate treatment strategy. Patients with CRPC can by treated with CRS plus IP and systemic chemotherapy, which has been suggested to prolong survival. In a prospective, randomized trial of this treatment regimen, the MST was 22.3 months [4, 18], and varied between 33 and 61 months in recent retrospective comparative studies [5, 19].

Although some prospective studies on CRPC are available [4, 20–22], our study analyzed the possibilities and limitations of CCRS without IP and modern systemic chemotherapy (consisting of oxaliplatin, irinotecan, cetuximab, or bevacizumab). The MST for all patients with CRPC in this study was 11.9 months, which is similar to the MST of patients with CRPC described in other reports [20]. When patients were divided into CCRS and ICCRS groups, the MST of the CCRS group was 29.8 months, which was better than the 13–22 months for select patients receiving HIPEC with mitomycin C [4, 9, 23–25]. However, our study did not find good survival results for HIPEC with oxaliplatin (MST; 33–61 months) [5, 19]. In a univariate analysis of the CCRS group, systemic chemotherapy was not an independent prognostic factor (Table 3). We consider that this might have been due to two potential reasons. First, the effects of treatment with CCRS were extremely potent. Second, the number of patients in the CCRS group and the number of patients receiving modern systemic chemotherapy were too small to adequately analyze.

Franko et al. reported a pooled subgroup analysis of the North Central Cancer Treatment Group phase III trials N9741 and N9841. These trials determined that systemic chemotherapy with FOLFOX was superior to irinotecan-based treatment regimens, irrespective of the carcinomatosis status [22]. Kerscher et al. evaluated the impact of changing the treatment in 256 patients with CRPC according to the management of CRPC in each era. That study demonstrated a trend toward modern systemic chemotherapy improving the prognosis for patients with CRPC [26]. However, that trial did not consider the effects of CCRS. Our study showed that modern systemic chemotherapy improved the prognosis of patients who underwent ICCRS on the basis of their CRPC status. In this analysis, treatment with irinotecan was not an independent prognostic factor (Table 3). However, treatment with both oxaliplatin and irinotecan showed a tendency to be a prognostic factor. The lack of significance may be attributable to the limited number of patients included.

The major limitations of this study included a question on the confidence in the survival results, because this was a nonrandomized study. Our study was not randomized because it would have been unethical to actively choose ICCRS, and our treatment strategy was to perform a curative operation whenever possible to improve the prognosis of patients with CRPC. We also did not analyze IP treatment or the PCI [27, 28], because treatment with IP is not yet part of the standard treatment protocol at our institution. The risk of morbidity and mortality after CCRS and IP is highly dependent on the institution, and this procedure should be restricted to institutions with expertise in the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis [29, 30]. There are few institutions in Japan with such expertise; therefore, the standard treatment for CRPC is CCRS and ICCRS, and not IP treatment. The PCI was not analyzed in this study because other means of scoring the peritoneal carcinomatosis status based upon the distance from the primary tumor (P0, no peritoneal carcinomatosis; P1, near; P2, middle; and P3, far) are used in Japan. P1, P2, and P3 are approximately equivalent to a PCI of 1–9, 4–18, and 7–39, respectively. It is difficult to perfectly compare the Japanese scores with the PCI, but CCR0 is equivalent to P1. Thus, the treatment concept for IP and the scoring system for peritoneal carcinomatosis differed based on the nationality of the patients.

In conclusion, this study determined that patients undergoing CCRS had a significantly longer OS than those undergoing ICCRS. Oxaliplatin and molecular-targeted drug therapies improved the OS in patients undergoing ICCRS. CCRS plus modern systemic chemotherapy without IP treatment had a similar effect to CCRS plus IP and systemic chemotherapy, and future trials for CRS should consider stratifying patients according to the CRPC status.

References

Lemmens VE, Klaver YL, Verwaal VJ, Rutten HJ, Coebergh JW, de Hingh IH. Predictors and survival of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2717–25.

Koppe MJ, Boerman OC, Oyen WJ, Bleichrodt RP. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: incidence and current treatment strategies. Ann Surg. 2006;243:212–22.

Jayne DG, Fook S, Loi C, Seow-Choen F. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1545–50.

Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, van Sloothen GW, van Tinteren H, Boot H, et al. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3737–43.

Elias D, Lefevre JH, Chevalier J, Brouquet A, Marchal F, Classe JM, et al. Complete cytoreductive surgery plus intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia with oxaliplatin for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:681–5.

Teo MC, Tan GH, Tham CK, Lim C, Soo KC. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in Asian patients: 100 consecutive patients in a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2968–74.

Park IJ, Choi GS, Lim KH, Kang BM, Jun SH. Metastasis to the sigmoid or sigmoid mesenteric lymph nodes from rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2009;249:960–4.

Yan TD, Black D, Savady R, Sugarbaker PH. Systematic review on the efficacy of cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4011–9.

Glehen O, Kwiatkowski F, Sugarbaker PH, Elias D, Levine EA, De Simone M, et al. Cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: a multi-institutional study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3284–92.

Goéré D, Malka D, Tzanis D, Gava V, Boige V, Eveno C, et al. Is there a possibility of a cure in patients with colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis amenable to complete cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy? Ann Surg. 2013;257:1065–71.

Saltz LB, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2013–9.

Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–42.

de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M, Homerin M, Hmissi A, Cassidy J, et al. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2938–47.

Van Cutsem E, Köhne C-H, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang C-R, Makhson A, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1408–17.

Kobayashi H, Enomoto M, Higuchi T, Uetake H, Iida S, Ishikawa T, et al. Validation and clinical use of the Japanese classification of colorectal carcinomatosis: benefit of surgical cytoreduction even without hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Dig Surg. 2010;27:473–80.

Mulsow J, Merkel S, Agaimy A, Hohenberger W. Outcomes following surgery for colorectal cancer with synchronous peritoneal metastases. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1785–91.

Klaver YL, Lemmens VE, de Hingh IH. Outcome of surgery for colorectal cancer in the presence of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:734–41.

Verwaal V, Bruin S, Boot H, van Slooten G, van Tinteren H. 8-year follow-up of randomized trial: cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2426–32.

Franko J, Ibrahim Z, Gusani NJ, Holtzman MP, Bartlett DL, Zeh HJ 3rd. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion versus systemic chemotherapy alone for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer. 2010;116:3756–62.

Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O, Beaujard AC, Rivoire M, Baulieux J, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE 1 multicentric prospective study. Cancer. 2000;88:358–63.

Folprecht G, Köhne C-H, Lutz M. Systemic chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. In: Ceelen W, editor. Peritoneal carcinomatosis. US: Springer; 2007. p. 425–40.

Franko J, Shi Q, Goldman CD, Pockaj BA, Nelson GD, Goldberg RM, et al. Treatment of colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis with systemic chemotherapy: a pooled analysis of north central cancer treatment group phase III trials N9741 and N9841. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:263–7.

Shen P, Hawksworth J, Lovato J, Loggie BW, Geisinger KR, Fleming RA, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin C for peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonappendiceal colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:178–86.

Glehen O, Cotte E, Schreiber V, Sayag-Beaujard AC, Vignal J, Gilly FN. Intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia and attempted cytoreductive surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Br J Surg. 2004;91:747–54.

Pilati P, Mocellin S, Rossi CR, Foletto M, Campana L, Nitti D, et al. Cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal intraoperative chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis arising from colon adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:508–13.

Kerscher AG, Chua TC, Gasser M, Maeder U, Kunzmann V, Isbert C, et al. Impact of peritoneal carcinomatosis in the disease history of colorectal cancer management: a longitudinal experience of 2,406 patients over two decades. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1432–9.

Jacquet P, Jelinek JS, Steves MA, Sugarbaker PH. Evaluation of computed tomography in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer. 1993;72:1631–6.

Elias D, Blot F, El Otmany A, Antoun S, Lasser P, Boige V, et al. Curative treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis arising from colorectal cancer by complete resection and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92:71–6.

Elias D, Gilly F, Quenet F, Bereder JM, Sidéris L, Mansvelt B, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: a French multicentric study of 301 patients treated with cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:456–62.

Glehen O, Gilly FN, Boutitie F, Bereder JM, Quenet F, Sideris L, et al. Toward curative treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonovarian origin by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116:5608–18.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yasuhumi Saito, Hiroyuki Sawada, Naoki Tanimine, Masashi Miguchi, Hiroaki Niitu, Syouichirou Mukai, and Takuya Yano for the acquisition of data and database maintenance. We also extend special thanks to Minoru Hattori for statistical support.

Conflict of interest

Tomohiro Adachi and co-authors have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adachi, T., Hinoi, T., Egi, H. et al. Oxaliplatin and molecular-targeted drug therapies improved the overall survival in colorectal cancer patients with synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis undergoing incomplete cytoreductive surgery. Surg Today 45, 986–992 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-014-1017-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-014-1017-y