Abstract

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative disease which is expected to become one of the leading causes of disability by the next years. This work aims to assess if balneotherapy and spa therapy can significantly improve Quality of Life (QoL) of patients with knee OA. Medline via PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and PEDro were systematically searched for articles about trials involving patients with knee OA and measuring the effects of balneotherapy and spa therapy on study participants’ QoL with validated scales. A qualitative and quantitative syntheses were performed. Seventeen studies were considered eligible and included in the systematic review. Fourteen trials reported significant improvements in at least one QoL item after treatment. Ten studies were included in quantitative synthesis. When comparing balneological interventions with standard treatment, results favored the former in terms of long-term overall QoL [ES = − 1.03 (95% CI − 1.66 to − 0.40)]. When comparing balneological interventions with sham interventions, results favored the former in terms of long-term pain improvement [ES = − 0.38 (95% CI − 0.74 to − 0.02)], while no significant difference was found when considering social function [ES = − 0.16 (95% CI − 0.52 to 0.19)]. In conclusion, even though limitations must be considered, evidence shows that BT and spa therapy can significantly improve QoL of patients with knee OA. Moreover, reduction of drug consumption and improvement of algofunctional indexes may be other beneficial effects. Further investigation is needed because of limited available data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most frequent musculoskeletal disorder and its prevalence will likely increase in the next 20 years due to the growing rates of obesity and longevity [1]. Osteoarthritis of the knee, the most common localization of OA, is the major cause of disability worldwide [2, 3]. Chronic pain and functional impairment with difficulty to perform daily living activities can cause a marked reduction in Quality of Life (QoL) [4]. Patients with knee OA can lose about 1.9 quality-adjusted-life years (QALY), like patients with metastatic breast cancer or cardiovascular diseases [5].

Current treatment of OA includes non-pharmacological (education, exercise, diet if necessary, and lifestyle changes) and pharmacological treatments, such as acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), selective COX-2 inhibitors, opioids, duloxetine and topical drugs [6, 7].

Balneotherapy (BT) is one of the most common non-pharmacological treatment for OA patients, with a beneficial effect on pain, stiffness, function and a favorable economic profile [8,9,10,11]. Balneotherapy indicates the use of thermal mineral waters, mud/peloid packs, natural gases (CO2, iodine, sulfur, radon, etc.) or hay baths for preventive, therapeutic, and rehabilitative purposes. Balneotherapy is often confused with Hydrotherapy (HT) or spa therapy. However, HT is the use of normal tap water for therapeutic purposes, while spa therapy indicates a complex intervention at a spa resort employing a number of different treatment modalities, including HT and BT, often combined with massage, exercise, physical therapy or rehabilitation [12, 13].

Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses mostly studied the efficacy of BT or spa therapy on pain and function in patients with knee OA [8,9,10,11]. In a systematic review by Harzy et al. data from nine (9) trials involving 493 patients were qualitatively assessed and results supported the efficacy of BT with thermal mineral water in improving pain and functional capacity of patients with knee OA for 24 weeks without any serious adverse event associated with balneological interventions [8]. In two other reviews on the topic, health benefits of BT with thermal mineral water and mud packs were reported to last even longer, up to 9 months after treatment, highlighting its usefulness in the treatment of a chronic condition like knee OA [9, 14]. An interesting meta-analysis of eight (8) trials about the effects of BT on symptomatology and function of patients with knee OA was performed by Matsumoto et al., underscoring a significant improvement in WOMAC pain, stiffness and physical function scores among patients treated with BT over controls [10]. Although these results highlight the importance of balneological interventions in improving the health status of patients with knee OA, the actual impact of BT and spa therapy on QoL has been less investigated.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to explore the possible effect of different BT treatments (thermal mineral baths and/or mud/peloid packs, or hay baths) and spa therapy on QoL in patients with knee OA. To better interpret results of meta-analyses about the impact of BT and spa therapy on QoL, variations of drug consumption within included trials are also evaluated. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the impact of BT and spa therapy on QoL of patients with knee OA.

Methods

The PRISMA statement was followed for this systematic review and meta-analysis [15]. Since there is no definite consensus about specific differences between QoL and Health-Related Quality of Life (HQoL), only the broader term QoL is used in the present work.

Trial selection criteria

Only randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) involving patients with knee OA diagnosed according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria were included [16]. There were no restrictions in terms of the type of clinical setting.

Trials with unspecified randomization and allocation concealment of study participants or with a non-random component in the sequence generation process were considered eligible to minimize publication bias and maximize retrievable evidence about the topic. These aspects were further considered for selection bias assessment.

Only studies in which intervention comprised thermal mineral water immersion, hay baths or mud/peloid pack applications were included. Trials were excluded when normal tap water was used to treat participants or when no clear information about water and mud/peloid composition or their source was provided.

All eligible trials were included regardless of the type of intervention administered to the comparison group.

Studies were included only if QoL was assessed with at least one of the following validated scales: the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS/AIMS2), the Disease Repercussion Profile (DRP), the EuroQoL (EQ-5D), the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP), the Patient Generated Index (PGI), the Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB), the RAQoL, the Short Form-36 (SF-36), the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP), the SIP-RA, the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Instruments (WHOQoL, WHOQoL-100, WHOQoL-Bref) [17], or the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) [18].

WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) and LAI (Lequesne’s Algofunctional Index for Knee) indexes were purposely excluded from the systematic review and meta-analysis to avoid pooling together data from algofunctional indexes and data from QoL scales, which specifically describe the impact of the disease on the patient’s QoL. However, data about WOMAC and LAI indexes from included trials were extracted and qualitatively analyzed (Supplementary Material A).

Studies were excluded from quantitative synthesis when essential data were missing or unclear; when no data were provided for selected follow-up period (2–3 months after treatment); when it was not possible to pool extracted data, or when comparison group was different from standard therapy or sham therapy. Observational studies were excluded. Manuscripts written in languages different from English were excluded.

Trial sources

Medline via PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database) were searched by two investigators independently (M.A., D.D.) for articles about trials involving patients with knee OA and studying the effects of thermal mineral baths, mud/peloid therapy, hay baths and spa therapy on participants’ QoL. All mentioned databases were screened up to December 2017.

Search

The following search strategies were used:

-

PubMed/Medline: “((knee[Title/Abstract] AND (osteoarthr* [Title/Abstract] OR arthritis[Title/Abstract] OR arthrosis[Title/Abstract] OR arthropathy[Title/Abstract])) OR gonarthr*[Title/Abstract]) AND (balneotherapy[Title/Abstract] OR hydrotherapy[Title/Abstract] OR fangotherapy[Title/Abstract] OR spa[Title/Abstract] OR mud[Title/abstract] OR peloid[Title/Abstract] OR thermal water[Title/Abstract] OR hay bath*[Title/Abstract])”.

-

Scopus: “TITLE-ABS-KEY ((((knee AND (osteoarthr* OR arthritis OR arthrosis OR arthropathy)) OR gonarthr*) AND (spa OR hydrotherapy OR balneotherapy OR mud OR fangotherapy OR peloid OR “thermal water” OR “hay bath*”))) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”))”.

-

Web of Science: “TOPIC: (((knee AND (osteoarthr* OR arthritis OR arthrosis OR arthropathy)) OR gonarthr*) AND (spa OR hydrotherapy OR balneotherapy OR mud OR fagotherapy OR peloid OR “thermal water” OR “hay bath*”)). Refined by: DOCUMENT TYPES: (ARTICLE) AND LANGUAGES: (ENGLISH)”.

-

Cochrane library: “knee osteoarthritis” AND “balneotherapy” in Title, Abstract, Keywords. In addition, the following terms were searched to retrieve all possible relevant articles: “balneotherapy”, “spa hydrotherapy”, “mud therapy”, “peloid therapy”, “fangotherapy”, “hay bath*”. Results of this additional search were pre-screened to assess their relevance and make sure they included a measurement of quality of life in patients with knee OA.

-

PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database): “Advance search with Therapy: hydrotherapy, balneotherapy; Body part: lower leg or knee; Method: clinical trial”.

Study selection and data collection process

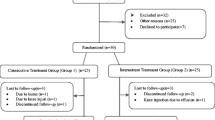

Details about the selection process of studies eligible for this review were summarized in a flowchart (Fig. 1). Results were screened and selected by two investigators independently (M.A., D.D.). In case of disagreement, items were discussed until consensus was reached. Extracted data are summarized in tables, grouped according to the type of control, as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

When data were only reported graphically, they were extracted from graphs with a plot digitizer. Data about QoL of one study [26] were collected from another article reporting a detailed analysis of data from the same trial [11].

When sample means and standard deviations were not available, they were estimated from sample medians and interquartile ranges with validated statistical tools [37, 38].

Data items

Collected data from included articles were the following ones: number of study participants, instruments used to measure QoL, number of therapy sessions, characteristics of intervention, report of significant (p < 0.05) differences in QoL items after treatment, namely, pre–post significant variations in intervention and comparison groups, significant differences between intervention and comparison groups after treatment, characteristics of standard treatment administered to all patients, use of a diary recording type and quantity of consumed drugs, other drugs taken by patients, relevant patients’ comorbidities at baseline, significant variations in drug consumption during study and follow-up periods.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The risk of bias for each included study was independently assessed by two investigators (M.A., D.D.) following the criteria of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for trials. Disagreements were discussed with the third investigator (A.F.) until consensus was reached. Performance bias was not considered a key domain, because thermal mineral baths, mud/peloid packs, hay baths and spa therapy require the patients’ participation and direct involvement. Detection bias was considered low when questionnaires were delivered by a blind researcher and unclear when self-completed by patients or when the method of administration was not indicated. Studies were considered at high risk of bias when there was a high risk of bias in at least one key domain or unclear risk of bias in at least two key domains. Studies were considered at unclear risk of bias if only one key domain had an unclear risk of bias. If all the key domains had a low risk of bias, the risk of bias of the entire study was reported to be low too.

Summary measures

Standardized mean difference (Hedges’ g) was used as a measure of effect size in the quantitative synthesis.

Synthesis of results

Results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 and discussed to obtain a qualitative synthesis.

The software used to perform the meta-analyses was “Review Manager” (RevMan, version 5.3).

Included studies were heterogeneous in terms of comparison group types. Pre–post effect size analysis was excluded due to possible biased outcomes [39]. On the basis of available data and considering methodological issues and the aim of this work, it was decided to perform three meta-analyses. The first meta-analysis (Fig. 2) summarized the effects of thermal mineral baths, mud/peloid therapy and spa therapy in adjunct to standard treatment compared to standard treatment only on overall QoL on a long-term (measured at a 2–3-month follow-up visit). The second and third meta-analyses (Figs. 3, 4) summarized the effects of thermal mineral baths, mud/peloid therapy, and spa therapy compared to sham therapy (tap water immersion or hot packs) on pain as a QoL item and on social function on a long-term (measured at a 2–3-month follow-up visit), respectively. These two items were selected, since they represent a physical and a psychosocial component of individual QoL. This decision was also made, because the studies that used sham therapy in the comparison group were heterogeneous in terms of adopted QoL scales; therefore, to achieve homogeneity among extracted data, only comparable items of the various adopted QoL scales were considered (applying linear transformations when required).

Forest plot of the first meta-analysis pooling data from studies investigating the effects of balneological interventions in adjunct to standard treatment compared to standard treatment alone on overall QoL on a long-term (measured at a 2–3-month follow-up visit). Caption: three subgroups are described, each of them characterized by a different type of balneological intervention (balneotherapy, phytobalneotherapy, spa therapy with mud/peloid packs). In each subgroup, studies are listed according to the first author’s surname. Means and standard deviations are reported in columns and a random-effect model was adopted to better estimate subgroup and overall size effects

Forest plot of the second meta-analysis pooling data from studies investigating the effects of balneological interventions with thermal mineral water or mud/peloid packs compared to sham therapy (tap water immersion or hot packs) on pain as a QoL item on a long-term (measured at a 2–3-month follow-up visit). Caption: two subgroups are described, each of them characterized by a different type of balneological intervention. In each subgroup, studies are listed according to the first author’s surname. Means and standard deviations are reported in columns and a random-effect model was adopted to better estimate subgroup and overall size effects

Forest plot of the third meta-analysis pooling data from studies investigating the effects of balneological interventions with thermal mineral water or mud/peloid packs compared to sham therapy (tap water immersion or hot packs) on social function as a QoL item on a long term (measured at a 2–3-month follow-up visit). Caption: two subgroups are described, each of them characterized by a different type of balneological intervention. In each subgroup, studies are listed according to the first author’s surname. Means and standard deviations are reported in columns and a random-effect model was adopted to better estimate subgroup and overall size effects

Studies included in the first meta-analysis adopted scales like HAQ, AIMS, EQ-5D, and SF-36, while studies included in the other meta-analyses employed item-specific scales such as NHP and SF-36. Evidence shows that a strong correlation exists among the above-mentioned QoL scales [40,41,42,43,44], so it can be assumed that, when one of them variates, the others report a proportional linear change. However, high heterogeneity among scales was present, since some scales associate improvement of QoL to positive variations with high values indicating good QoL, while others to negative variations with high values indicating poor QoL. Moreover, specific scale elements which assess social QoL are measured with an item which oppositely changes in response to the same variation. For example, in the SF-36 an improvement of social QoL is reported as an improvement of social function, while in the NHP it is described as a reduction of social isolation. To overcome this heterogeneity and allow a possible comparison, in the first meta-analysis (Fig. 2) sample data were normalized to a 0–3 range with high numbers indicating poor QoL, as it happens for the HAQ. In the other two meta-analyses (Figs. 3, 4), sample data were normalized to a 0–100 range with high numbers indicating poor QoL, as it happens for the NHP. Social function was adopted as an item to measure social QoL so that the higher is social QoL the better is social function and the lower the score. Therefore, data from different scales were normalized with appropriate scale factors to obtain comparable means, and standard deviations were converted accordingly with validated methods [45]. After that, means were linearly shifted to align them with no additional changes for standard deviations, since linear shifts imply no modifications of measures of dispersion and variability.

Considering high heterogeneity of included studies, a random-effect model was adopted to better estimate subgroup and overall size effects. I2 was used as a measure of consistency.

Risk of bias across studies

When possible, funnel plots were used to visually assess potential publication bias (Supplementary Material B).

Additional analyses

In each meta-analysis, data were pooled in subgroups according to intervention type and an overall effect size was calculated.

Results

After full-text assessment, seventeen (17) articles were considered eligible for qualitative synthesis. Main data of included studies are summarized in Table 1. Efficacy of thermal mineral baths, mud/peloid packs and spa therapy to significantly influence the patients’ QoL was compared with the efficacy of standard treatment [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], HT (tap water immersion) [29,30,31], and sham mud/peloid therapy (hot packs) [32,33,34,35]. Standard treatment was defined as a combination of pharmacological and physical interventions mainly characterized by a drug-based approach implying the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), other analgesics and/or chondroprotective agents. One study compared spa therapy (including mud/peloid packs) administered consecutively with the same regimen administered intermittently [36]. Fourteen (14) studies showed significant changes in at least one QoL item after the treatment in the intervention group [20, 22, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. In two studies variations were not statistically significant [21, 23] and in one study this information was not reported [24].

For some of included studies which displayed significant improvements in QoL [20, 22, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], it was possible to extract data about single QoL items, suggesting that scores describing both physical (such as pain and mobility) and psychosocial (such as vitality, social function or emotional role) aspects of QoL ameliorated in the intervention group (further details are reported in Table 1). In two studies even sleep, evaluated as a QoL item, was reported to improve after treatment in balneological intervention groups [31, 32].

Although WOMAC and LAI indexes were not considered for the systematic review and meta-analysis, in Supplementary Material A significant improvements and variations in WOMAC and LAI indexes in patients studied in included trials are reported.

Table 2 summarizes data about significant variations in drug consumption during the study and the follow-up periods, and characteristics of standard treatment administered to patients of included trials. Ten (10) studies [20,21,22, 24,25,26,27,28, 32, 35] reported data about variations in drug consumption, and eight (8) [20,21,22, 24,25,26,27,28] of them reported significant reductions (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 or p < 0.001) of drug consumption in the intervention group compared to control group. Eight (8) studies [20,21,22, 24,25,26,27, 35] reported significant reductions (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 or p < 0.001) of drug consumption within intervention group compared to baseline during the course of the study. Table 2 also describes characteristics of standard treatment administered to patients, reports if during the study it was kept a diary to record type and quantity of used drugs, and indicates the number of patients taking other medicines or with relevant comorbidities at baseline.

The overall risk of bias of all included trials is reported in Table 1, whereas further details are provided in Table 3. Overall risk of bias was described as low for two studies [20, 21], unclear for six studies [22, 25, 26, 29, 35, 36], high for nine studies [20, 23, 24, 27, 30,31,32,33,34].

Ten (10) studies were included in quantitative syntheses [20, 21, 23, 25,26,27,28, 31, 33, 34].

Seven (7) studies were included in the first meta-analysis (Fig. 2) whose results (overall effect size of − 1.03 with 95% CI − 1.66 to − 0.40) showed that balneological interventions in adjunct to standard treatment are significantly more effective than standard treatment alone in improving QoL in patients with knee OA [20, 21, 23, 25,26,27,28].

Three (3) studies were included in the second and third meta-analyses (Figs. 3, 4), in which effects on pain and social function of real balneological interventions (thermal mineral baths or mud/peloid packs) were compared with effects of sham interventions (tap water immersion or hot packs) [31, 33, 34]. Results favored real balneological interventions when considering improvement of pain as a QoL item (overall effect size of − 0.38 with 95% CI − 0.74 to − 0.02), while for social function no evidence in favor of one intervention over the other was reported (overall effect size of − 0.16 with 95% CI − 0.52 to 0.19).

High heterogeneity was reported in the first meta-analysis (Fig. 2) with I2 = 93%, while a value of I2 = 0% was reported for the second and third meta-analyses (Figs. 3, 4). Asymmetry in the funnel plot (Supplementary Material B), feasible only with studies included in the first meta-analysis, suggested a potential risk of publication bias with a possible over-representation of trials with low precision and with results in favor of BT and spa therapy.

Discussion

The impact of knee OA on individual QoL is comparable to that one experienced by patients with other chronic conditions such as cardiovascular or pulmonary diseases [3, 4]. BT represents a common complementary therapy in the management of OA with beneficial effects on pain, stiffness, and function, as reported by recent systematic reviews [10, 14]. Evidence from observational studies indicates that BT and spa therapy may be also effective in improving QoL of patients with knee OA [46,47,48].

Table 1 shows that overall evidence from included trials favors BT and spa therapy when considering significant changes in QoL in a pre–post treatment assessment. Three studies reported no information [24] or no significant changes in the intervention group after treatment [21, 23]. However, significant differences were described in two of them when comparing intervention group with comparison group after treatment [21, 24]. In one study [23], significant changes in QoL were reported neither in the intervention group after treatment, nor when intervention group was compared with control group after treatment. Despite that this study is the included trial with the highest number of participants, and is an important reference in the field, it reported a considerable attrition rate and employed a combination of hot mineral baths, mud/peloid packs, hydro-massage, manual therapy, and exercise, so it didn’t allow to precisely estimate to what extent each single intervention interfered with the others when considering QoL outcomes.

When investigating the effects of balneological interventions on knee OA, it is important to consider pharmacological treatments taken by patients and whether studied interventions can determine significant variations in drug consumption. Data from Table 2 show that, although from a qualitative point of view, balneological interventions can reduce drug consumption and this is important, especially considering the toxicity of NSAIDs, as well as their cost [20]. This aspect needs to be taken into account when interpreting results of meta-analyses on QoL.

Another aspect to consider is that, among included trials in which WOMAC and/or LAI indexes were assessed, significant improvements in these algofunctional scales were reported after intervention in patients treated with BT or spa therapy underscoring the importance of these balneological interventions in directly influencing also the patient’s health and functional status.

Results of quantitative analysis favored balneological interventions in adjunct to standard treatment compared to standard treatment alone when evaluating effects on a long-term overall QoL of patients with knee OA. Findings also show that real balneological interventions (hot mineral baths or mud/peloid packs) were significantly better than sham balneological interventions (tap water immersion or hot packs) in improving pain as a QoL item. This difference was probably due to specific (hydromineral and crenotherapeutic) mechanisms of action of thermal mineral waters and therapeutic muds/peloids with their chemo-physical properties, which can modulate endocrinological changes responsible for inflammation and pain reduction [25]. On the other hand, social function did not appear to be influenced by the treatment per se, maybe because, regardless of the type of intervention (real or sham), patients were asked for a short period to regularly go to a spa center, where they could relax, socialize with other people and where they were carefully assessed by dedicated physicians. Both real and sham balneological interventions may enhance self-perception of well-being and social function, possibly thanks to common placebo effects, which are mainly the rituality itself of an intervention, the treatment context and the patient–clinician relationship [49, 50]. Moreover, detailed medical interviews are reported to be beneficial for patients even in terms of psychosocial QoL, compliance, and satisfaction [51], and consist, in fact, of a true intervention in terms of rituality.

Limitations

Included studies were heterogeneous in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics of patients (age, sex, disease severity and duration, obesity and other comorbidities), comparison group type, association of balneological interventions with non-balneological treatments (exercises, massage, physical therapy, etc.), and scales used to measure the participants’ QoL, as shown in Table 1. To pool data from different trials, it was, therefore, necessary to use approximations which were considered acceptable because of scarce data about the topic and because of the nature of analyzed outcomes. Trials were conducted in different countries and, even though questionnaires were translated in the participants’ native language, social and cultural differences may have played a role in determining the patients’ perceived and reported QoL. Moreover, the the overall risk of bias of included studies tended to be high. Although potential publication bias has to be considered, it is to acknowledge that scarce evidence exists about the topic and most studies involved a limited number of participants. Funnel plot test has been performed only for the first meta-analysis with a small number of included studies. Furthermore, funnel plots have to be interpreted with caution, because even if they are widely used, it is not completely clear whether they are accurate tools to predict publication bias [52].

Conclusions

In conclusion, even though limitations of included studies must be taken into account, evidence shows that BT and spa therapy can significantly improve QoL of patients with knee OA. Moreover, BT and spa therapy may have a role in the reduction of drug consumption and improvement of algofunctional indexes among patients with knee OA. More trials with a higher number of patients and different types of balneological interventions are needed to better determine their effects on QoL. Furthermore, it is relevant to evaluate to what extent different chemical and physical properties of waters and muds/peloids may influence results. Further investigation is needed to better understand which QoL items are more likely to ameliorate in response to balneological treatments.

References

Zhang Y, Jordan JM (2010) Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med 26(3):355–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.001

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R et al (2012) Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380(9859):2197–2223. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4

Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D et al (2014) The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 73:1323–1330. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763

Hunter DJ, Schofield D, Callander E (2014) The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 10:437–441. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2014.44

Losina E, Walensky RP, Reichmann WM et al (2011) Impact of obesity and knee osteoarthritis on morbidity and mortality in older americans. Ann Intern Med 154:217–226. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00001

Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT et al (2012) American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res 64:465–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21596

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC et al (2014) OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartil 22:363–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003

Harzy T, Ghani N, Akasbi N, Bono W, Nejjari C (2009) Short- and long term therapeutic effects of thermal mineral waters in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rheumatol 28:501–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-009-1114-2

Tenti S, Cheleschi S, Galeazzi M, Fioravanti A (2015) Spa therapy: can be a valid option for treating knee osteoarthritis? Int J Biometeorol 59:1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-014-0913-6

Matsumoto H, Hagino H, Hayashi K, Ideno Y, Wada T, Ogata T, Akai M, Seichi A, Iwaya T (2017) The effect of balneotherapy on pain relief, stiffness, and physical function in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol 36:1839–1847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3592-y

Ciani O, Pascarelli NA, Giannitti C, Galeazzi M, Meregaglia M, Fattore G, Fioravanti A (2017) Mud-bath therapy in addition to usual care in bilateral knee osteoarthritis: an economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res 69:966–972. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23116

Gutenbrunner C, Bender T, Cantista P, Karagülle Z (2010) A proposal for a worldwide definition of health resort medicine, balneology, medical hydrology and climatology. Int J Biometeorol 54:495–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-010-0321-5

Fioravanti A, Karagülle M, Bender T, Karagülle MZ (2017) Balneotherapy in osteoarthritis: facts, fiction and gaps in knowledge. Eur J Integr Med 9:148–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2017.01.001

Forestier R, Erol Forestier F, Francon A (2016) Spa therapy and knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 59:216–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2016.01.010

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D et al (1986) Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum 29:1039–1049. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780290816

Carr A (2003) Adult measures of Quality of Life: The Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS/AIMS2), Disease Repercussion Profile (DRP), EuroQoL, Nottingham Health Profile (NHP), Patient Generated Index (PGI), Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB), RAQoL, Short Form-36 (SF-36), Sickness Impact Profile (SIP), SIP-RA, and World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Instruments (WHOQoL, WHOQoL-100, WHOQoL-Bref). Arthritis Care Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.11414

Bruce B, Fries JF (2003) The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-20

Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Blackmore H, Kitas GD (2011) Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Rheumatol Int 31(11):1409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-1999-3

Fioravanti A, Giannitti C, Bellisai B, Iacoponi F, Galeazzi M (2012) Efficacy of balneotherapy on pain, function and quality of life in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Int J Biometeorol 56(4):583–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-011-0447-0

Fioravanti A, Bellisai B, Iacoponi F, Manica P, Galeazzi M (2011) Phytothermotherapy in osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Altern Complement Med 17(5):407–412. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2010.0294

Antúnez LE, Puértolas BC, Burgos BI, Payán JMP, Piles STT (2013) Effects of mud therapy on perceived pain and quality of life related to health in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Reumatología Clínica (English Edition) 9(3):156–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reumae.2013.03.001

Forestier R, Desfour H, Tessier JM, Françon A, Foote AM, Genty C, Rolland C, Roques CF, Bosson JL (2009) Spa therapy in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis, a large randomised multicentre trial. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2009.113209

Nguyen M, Revel M, Dougados M (1997) Prolonged effects of 3 week therapy in a spa resort on lumbar spine, knee and hip osteoarthritis: follow-up after 6 months. A randomized controlled trial. Br J Rheumatol 36(1):77–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/36.1.77

Fioravanti A, Iacoponi F, Bellisai B, Cantarini L, Galeazzi M (2010) Short-and long-term effects of spa therapy in knee osteoarthritis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 89(2):125–132. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181c1eb81

Fioravanti A, Bacaro G, Giannitti C, Tenti S, Cheleschi S, Guidelli GM, Pascarelli NA, Galeazzi M (2015) One-year follow-up of mud-bath therapy in patients with bilateral knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, single-blind controlled trial. Int J Biometeorol 59(9):1333–1343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-014-0943-0

Cantarini L, Leo G, Giannitti C, Cevenini G, Barberini P, Fioravanti A (2006) Therapeutic effect of spa therapy and short wave therapy in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, single blind, controlled trial. Rheumatol Int 27(6):523–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-006-0266-5

Branco M, Rêgo NN, Silva PH, Archanjo IE, Ribeiro MC, Trevisani VF (2016) Bath thermal waters in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 52(4):422–430

Kulisch A, Benkö A, Bergmann A et al (2014) Evaluation of the effect of Lake Hévíz thermal mineral water in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled, single-blind, follow-up study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 50:373–381

Sherman G, Zeller L, Avriel A, Friger M, Harari M, Sukenik S (2009) Intermittent balneotherapy at the Dead Sea area for patients with knee osteoarthritis. Isr Med Assoc J 11(2):88

Yurtkuran M, Yurtkuran M, Alp A, Nasırcılar A, Bingöl Ü, Altan L, Sarpdere G (2006) Balneotherapy and tap water therapy in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int 27(1):19–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-006-0158-8

Evcik D, Kavuncu V, Yeter A, Yigit İ (2007) The efficacy of balneotherapy and mud-pack therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Jt Bone Spine 74(1):60–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.03.009

Güngen G, Ardic F, Fιndıkoğlu G, Rota S (2012) The effect of mud pack therapy on serum YKL-40 and hsCRP levels in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int 32(5):1235–1244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-010-1727-4

Sarsan A, Akkaya N, Özgen M, Yildiz N, Atalay NS, Ardic F (2012) Comparing the efficacy of mature mud pack and hot pack treatments for knee osteoarthritis. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 25(3):193–199. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-2012-0327

Tefner IK, Gaál R, Koroknai A, Ráthonyi A, Gáti T, Monduk P, Kiss E, Kovács C, Bálint G, Bender T (2013) The effect of Neydharting mud-pack therapy on knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, controlled, double-blind follow-up pilot study. Rheumatol Int 33(10):2569–2576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-013-2776-2

Özkuk K, Gürdal H, Karagülle M, Barut Y, Eröksüz R, Karagülle MZ (2017) Balneological outpatient treatment for patients with knee osteoarthritis; an effective non-drug therapy option in daily routine? Int J Biometeorol 61(4):719–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-016-1250-8

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T (2014) Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 14(1):135. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T (2016) Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280216669183

Cuijpers P, Weitz E, Cristea IA, Twisk J (2017) Pre-post effect sizes should be avoided in meta-analyses. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 26(4):364–368. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000809

Taccari E, Spadaro A, Rinaldi T, Riccieri V, Sensi F (1998) Comparison of the Health Assessment Questionnaire and Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Revue du rhumatisme (English Ed) 65(12), 751–758

Kvien TK, Kaasa S, Smedstad LM (1998) Performance of the Norwegian SF-36 Health Survey in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. II. A comparison of the SF-36 with disease-specific measures. J Clin Epidemiol 51(11):1077–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00099-7

Söderman P, Malchau H (2000) Validity and reliability of Swedish WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index: a self-administered disease-specific questionnaire (WOMAC) versus generic instruments (SF-36 and NHP). Acta Orthop Scand 71(1):39–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016470052943874

Salaffi F, Leardini G, Canesi B, Mannoni A, Fioravanti A, Caporali R, Lapadula G, Punzi L (2003) Gonarthrosis and Quality Of Life Assessment (GOQOLA) Reliability and validity of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index in Italian patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartil 11:551–560

Gignac MA, Cao X, Mcalpine J, Badley EM (2011) Measures of disability: Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2 (AIMS2), Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2-Short Form (AIMS2-SF), The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Long-Term Disability (LTD) Questionnaire, EQ-5D, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHODASII), Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI), and Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument-Abbreviated Version (LLFDI-Abbreviated). Arthritis Care Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20640

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR (2009) Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley, Chichester

Gaál J, Varga J, Szekanecz Z, Kurko J, Ficzere A, Bodolay E, Bender T (2008) Balneotherapy in elderly patients: effect on pain from degenerative knee and spine conditions and on quality of life. Isr Med Assoc J 10(5):365

Yilmaz B, Goktepe AS, Alaca R, Mohur H, Kayar AH (2004) Comparison of a generic and a disease specific quality of life scale to assess a comprehensive spa therapy program for knee osteoarthritis. Jt Bone Spine 71(6):563–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2003.09.008

Guillemin F, Virion JM, Escudier P, de Talancé N, Weryha G (2001) Effect on osteoarthritis of spa therapy at Bourbonne-les-Bains. Jt Bone Spine 68(6):499–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1297-319X(01)00314-1

Benedetti F, Pollo A, Lopiano L, Lanotte M, Vighetti S, Rainero I (2003) Conscious expectation and unconscious conditioning in analgesic, motor, and hormonal placebo/nocebo responses. J Neurosci 23(10):4315–4323

Miller FG, Kaptchuk TJ (2008) The power of context: reconceptualizing the placebo effect. J R Soc Med 101(5):222–225. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2008.070466

Goold SD, Lipkin M (1999) The doctor–patient relationship. J Gen Intern Med 14(S1):26–33. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00267.x

Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Schmid CH, Olkin I (2006) Evidence based medicine: the case of the misleading funnel plot. Br Med J 333(7568):597. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.333.7568.597

Funding

The authors received no funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design of the work: MA, DD, and AF. Data collection: MA and DD. Data analysis and interpretation: MA, DD, and AF. Drafting the article: MA, DD, and AF. Critical revision of the article: MA, DD, and AF. Final approval of the version to be published: MA, DD, and AF.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Antonelli Michele, Donelli Davide, and Fioravanti Antonella declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Disclaimer

No part of the manuscript was copied from elsewhere. This manuscript has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Antonelli, M., Donelli, D. & Fioravanti, A. Effects of balneotherapy and spa therapy on quality of life of patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int 38, 1807–1824 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-018-4081-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-018-4081-6