Abstract

Spa therapy and short wave therapy are two of the most commonly used non-pharmacological approaches for osteoarthritis. The aim of this study was to assess their efficacy in comparison to conventional therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee in a single blind, randomized, controlled trial. Seventy-four outpatients were enrolled; 30 patients were treated with a combination of daily local mud packs and arsenical ferruginous mineral bath water from the thermal resort of Levico Terme (Trento, Italy) for 3 weeks; 24 patients were treated with short wave therapy for the same period and 20 patients continued regular, routine ambulatory care. Patients were assessed at baseline, upon completion of the 3-week treatment period, and 12 weeks later. Spa therapy and short wave therapy both demonstrated effective symptomatic treatment in osteoarthritis of the knee at the end of the treatment, but only the spa therapy was shown to have efficacy persistent over time. Our study demonstrated the superiority of arsenical ferruginous spa therapy compared to short wave therapy in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee, probably in relationship to the specific effects of the minerals in this water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common rheumatic disease in developed countries [1].

Conservative treatment of OA is mainly based on symptomatic drugs, such as analgesic or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); adverse events are not rare, especially in older patients [2].

These motives often induce recourse to other complementary or alternative therapies [3].

Spa therapy is one of the most commonly used non-pharmacological approaches for OA. The efficacy of spa treatments in rheumatic diseases has been bolstered by ancient tradition, but in spite of their long history and popularity, only a few randomized, controlled trials on the use of these therapies in patients with rheumatic diseases have been conducted [4–11].

The mechanisms of action of mud packs and baths are not completely known, and it is difficult to distinguish the efficacy of the thermal method from the benefits that could be derived from a stay in the spa environment [12].

For this reason, spa treatments are still being discussed and their role in modern medicine is still not clear [13].

Short wave therapy is another non-pharmacological treatment that is often used in the treatment of OA, but its efficacy has still not been clearly documented [14, 15].

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of spa therapy and of short wave therapy, in comparison to conventional therapy, in patients with OA of the knee in a single-blind controlled randomized study.

Materials and methods

Seventy-four outpatients with primary OA of the knee and fulfilling the ACR criteria [16] of both sex, aged between 46 and 84 years, were included in the study. All patients had been symptomatic for at least 12 months before inclusion in the study. Radiological staging was carried out using the Kellgren method [17]; patients with a radiological score of I–III were included in the study (Table 1).

Exclusion criteria were severe co-morbidity of heart, lung, liver, cerebrum, thyroid gland or kidney, acute illness, juvenile diabetes, varices, systemic blood diseases, neoplasms, pacemaker, pregnancy or nursing. Patients were also excluded that had thermal treatments or a cycle of short wave therapy, joint lavage, arthroscopy or treatment with hyaluronic acid during the past 6 months or that had been treated with intra-articular corticosteroids during the past 3 months, as well as all patients that had been treated with chondroprotective agents less than 6 months before the study.

All patients underwent general medical evaluation and rheumatologic examination by the same physician before of the start of the study.

At the screening visit, blood samples were taken for erithrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), c-reactive protein (CRP), electrolytes, creatinine and complete blood count evaluation and a urinalysis were carried out.

All the demographic, anamnestic and clinical data were collected on an identical questionnaire.

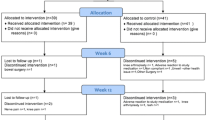

After confirming fulfilment of the screening criteria defined above and, after written informed consent, patients were randomly allocated to three groups: group I (30 patients) was treated with a combination of daily local mud packs and arsenical ferruginous mineral bath water; group II (24 patients) was treated with short wave therapy and group III (20 patients) (control group) continued regular routine ambulatory care.

All selected patients came to the area adjoining the thermal spa at Levico and continued to live at home and to carry out their daily routines.

Group I patients were treated daily at the thermal spa at Levico Terme (Trento, Italy), during the 2002–2003 season with a combination of mud packs applied on both knees for 20 min at an initial temperature of 45°C and with arsenical ferruginous mineral bath water at 38°C for 15 min for a total of 15 applications carried out over a period of 3 weeks according to standardized schedules [7]. The mineral water of Levico is characterized by an elevated content of Iron (Fe++, 1,751 mg/L) and of Arsenic (H2AsO3, 12 mg/L); for therapeutic use, it is diluted with tap water in a proportion of 1:2.

Group II patients were treated on both knees with applications of short wave diathermy using the SIMENS Ultraterm 642 E. Each patient received 10 treatments of 15 min, three times a week over a period of 3 weeks, according to the standardized schedules [14].

It was recommended to patients in all three groups that they should continue their usual, already established pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments, with the single exception of analgesic drugs (500 mg acetaminophen tablets) and NSAIDs (150 mg Diclofenac tablets, 20 mg Piroxicam tablets, 750 mg Naproxen tablets) were to be consumed freely and noted daily in a diary.

Each patient was examined, after basal screening, three consecutive times; immediately after the beginning of thermal or short wave therapy (T0), after 3 weeks (T1), and 12 weeks after the beginning of the study (T2).

All patients were examined and assessed by the same rheumatologist at the University center who was blind to the mode of treatment.

Clinical assessments at each examination included:

-

Spontaneous pain on a 0–100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) with zero for the absence of pain.

-

The Lequesne Index of severity of knee OA [18].

-

Quality of life recorded by the Arthritis impact measurement scale (AIMS1) [19, 20].

-

NSAIDs and analgesic intake reported in a daily diary given to each patient. The analgesic consumption score was calculated by the sum of tablet intake in each group. The NSAIDs consumption score was expressed as mg equivalence of diclofenac, according to a previously validated and published scale [21].

-

The overall assessment of efficacy by the patients was expressed as excellent, good, slight and nil.

For the whole period of the study, it was recommended that the patients should not modify their therapeutic program (for drug treatments as well as physio-kinesitherapy) except for the occurrence of adverse events. In particular, we recommended that they should not have corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid infiltrations, arthroscopic surgery or joint lavage, and that they should not begin treatment with new chondroprotective agents. The only exception was, of course, the consumption of NSAIDs and analgesics. All adverse events, whether spontaneously reported by the patients or observed by the physician at the thermal spa or by the physician who controlled the short wave therapy sessions, were reported on a diary card, noting the severity and the possible correlations with the treatments. The diary card was given to us at the end of the study, and serious adverse events were to be immediately reported to the Rheumatology Unit of the University of Siena and the patient was to be excluded from the study.

The study protocol followed the Principles of the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Siena.

Statistical analysis

The test for the profile of sex and radiological status and the Student’s t test for age, weight, height and the duration of disease were used to evaluate the homogeneity of the three groups in basal conditions.

Multivariate analysis of variance for repeated measures (MANOVA) was performed to compare the VAS, Lequesne’s index, the AIMS1 score, and daily NSAIDs and analgesic intake at each assessment period and between the groups. Bonferroni’s correction was applied to multiple testing.

The x2-test was used for comparison of the percentages of patients’ opinions and of adverse effects.

Results

Baseline comparison of the three groups showed no statistically significant differences in patient characteristics (Table 1).

Objective examinations and the clinical data obtained at the basal visit showed the presence of some pathologies associated with gonarthrosis. In particular, in the group treated with spa therapy two patients were carriers of prostatic hypertrophy, six presented arterious hypertension that was controlled well with anti-hypertensive drugs, four patients were carriers of scars at gastric ulcer sites, three had non-insulin dependent diabetes controlled with oral antidiabetic agents and one patient was affected with psoriasis. In the group treated with short wave therapy, two patients were affected with arterious hypertension and two with non-insulin dependent diabetes that was well compensated with therapy, one had a gastric ulcer and two had cardiopathy in hemodynamic compensation. In the control group, six patients presented arterious hypertension, well controlled with pharmacological treatment, three patients had non-insulin dependent diabetes and one had a gastric ulcer.

All of the patients selected completed the study.

At the end of the treatment, we observed a significant reduction (P < 0.01) in spontaneous pain at the end of the cycle (3 weeks) for the groups treated with spa therapy and with short wave diathermy, whereas a significant worsening (P < 0.01) was noted in the control group (Fig. 1). After 12 weeks, group I showed a further improvement compared to basal values (P < 0.01), while group II showed a statistically significant worsening compared to basal values (P < 0.01). The control group demonstrated a progressive and significant worsening in VAS (Fig. 1).

Spontaneous pain on a 0–100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS). **P < 0.01 versus basal time, *P < 0.05 versus basal time, oo P < 0.01 C versus SPA and SW. T0 beginning of the study. T1 3 weeks after the beginning of the study. T2 12 weeks after the beginning of the study. SPA group treated with spa therapy, SW group treated with short wave therapy, C control group

At the examination after 3 weeks of treatment, a comparison of the two groups undergoing treatment did not show significant differences, yet there was a significant difference between the control group and those undergoing treatment (P < 0.01); at the examination after 12 weeks of treatment there was a statistically significant difference between the group undergoing spa therapy and the other two groups (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1).

Figure 2 shows the Lequesne’s index score for gonarthrosis, from which a significant decrease (P < 0.01) emerged after 3 weeks for each of the treated groups compared to the control group. This result was maintained 12 weeks later only for the group undergoing spa therapy.

Lequesne’s index score of severity of knee OA. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, oo P < 0.01 C versus SPA o P < 0.05 C versus SW, oo P < 0.01 C versus SPA and SW. T0 beginning of the study. T1 3 weeks after the beginning of the study. T2 12 weeks after the beginning of the study. SPA: group treated with spa therapy, SW group treated with short wave therapy, C control group

Figure 3 shows the movement of the scores of the self-administrated questionnaire AIMS1. There was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.01) between groups I and II at basal conditions, with a worse score for group II. At the end of the treatment, there was a significant improvement (P < 0.01) in groups I and II which was maintained after 12 weeks only for group I.

Arthritis impact measurement scale score (AIMS1). **P < 0.01, oo P < 0.01 C versus SPA, SW and C versus SPA, o P < 0.05 SW versus SPA. T0 beginning of the study. T1 3 weeks after the beginning of the study. T2 12 weeks after the beginning of the study. SPA group treated with spa therapy, SW group treated with short wave therapy, C control group

Regarding the use of symptomatic drugs, there was a marked reduction at the end of the treatment cycle, both in the groups of patients undergoing spa therapy and short wave therapy. This decrease lasted 12 weeks only for the first group, while in group II we observed a significant resumption in the consumption of drugs. In the control group there was a progressive increase in the consumption of symptomatic drugs at 3 weeks, with a fundamental stabilization after 12 weeks (Fig. 4a, b).

a Acetaminophen daily consumption (tablets) over time at entry, after 3 and 12 weeks in SPA, SW and C groups. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, oo P < 0.01 C versus SPA and SW, C and SW versus SPA. T0 beginning of the study. T1 3 weeks after the beginning of the study. T2 12 weeks after the beginning of the study. SPA group treated with spa therapy, SW group treated with short wave therapy, C control group. b NSAIDs daily consumption (score) over time at entry, after 3 and 12 weeks in SPA, SW and C groups. **P < 0.01 versus basal time, *P < 0.05 versus basal time, oo P < 0.01 C versus SPA and SW, C and SW versus SPA. T0 beginning of the study. T1 3 weeks after the beginning of the study. T2 12 weeks after the beginning of the study. SPA group treated with spa therapy, SW group treated with short wave therapy, C control group

Regarding the satisfaction of the patients with the clinical efficacy of treatments at the end of the study, a good-excellent opinion was obtained from 95.8% of the patients treated with spa therapy, from 40% of the group undergoing short wave therapy and from 37.40% of the control group (P < 0.01).

Regarding clinical tolerability, none of the 24 patients treated with short wave therapy mentioned side effects connected to the treatments. In the group treated with spa therapy, 9 patients presented side effects due to treatments but these were of light intensity and they did not interrupt the therapy. In the control group, 4 patients presented prevalently gastrointestinal side effects, probably correlated to the higher recourse to symptomatic drugs compared to patients in the other two treated groups; in particular, 3 patients presented epigastralgia, and one of these complained of gastric pyrosis.

Discussion

This study confirms previous data [4, 6, 7, 10, 11] suggesting a symptomatic effect of spa therapy in the treatment of knee OA.

The efficacy of spa therapy was significant in all of the assessed variables (VAS, Lequesne’s index, AIMS1, symptomatic drugs consumption, patient’s opinion), both at examinations at the end of therapy and at the 12 week follow-up.

In patients treated with short wave therapy, a significant benefit was evident immediately after the end of treatment, but at the 12 week follow-up examination there was a worsening in functional and pain symptoms, in agreement with that demonstrated by other authors [14].

A gradual worsening was evident in the control group (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

The reduction in the consumption of symptomatic drugs (analgesics and NSAIDs) shown in the group treated with spa therapy appeared to be particularly important, also after the 12 week follow-up. In the group treated with short wave therapy, the reduction in the consumption of symptomatic drugs was significant only at the examination at the end of treatment; the control group showed an increase in recourse to analgesics and NSAIDs at the 3 week examination and a stabilization at the 12 week follow-up (Fig. 4a, b).

The savings in the consumption of symptomatic drugs induced by spa therapy is particularly important, considering the toxicity of NSAIDs [2], particularly in the elderly and the cost of their use is often associated with gastro-protective therapies.

Verhagen et al. [13] emphasized the importance of quality of life indexes as outcome measurements in spa studies. Although there have been a number of spa studies on knee OA [4, 6, 7, 10, 11], few of them used any type of quality of life assessment [7, 22, 23].

In this study, we used the AIMS1, a validated disease-specific scale of quality of life (19) for OA of the knee, in the Italian language [20].

The reduction in the AIMS1 score, persistent over time, in the group treated with arsenical- ferruginous spa therapy (Fig. 3) is an evident demonstration of the efficacy of this therapy on the various aspects which characterize OA.

The mechanisms by which spa therapy improves the symptoms of OA are not fully understood [12]. The effects of balneotherapy and of the application of mud packs are, in part, relative to temperature. Muscle tone, joint mobility and pain intensity may be influenced by thermal stimuli [12].

Furthermore, mud baths induced a neuroendocrine reaction causing an increase in serum levels of opioid peptides, such as endorphins and enkephalins, which may explain the analgesic effects of spa therapy [24]. It was recently demonstrated that thermal mud pack therapy induces, in patients with OA, a reduction in circulation levels of Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), Leukotriene B4 [25], tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) [26, 27] and metalloproteinases-3 (MMP-3) [28], as well as increases in antioxidant defence [29].

Many other non-specific factors may also contribute to the effects observed after spa therapy, including changes of environment, pleasant scenery and the absence of work duties [12, 13]. In our study, however, in order eliminate these factors, all of the patients were residents of the area near the thermal spa and they continued their work activities without modifying their life styles.

Another aspect that often contributes to amplifying the effect of spa therapy is the frequent association of physio-kinesitherapy. These treatments were excluded from the protocol of this study if they had not already begun and were not already established.

The therapeutic effect of short wave therapy is based on mechanical energy. However, there have been only few controlled trials evaluating short wave diathermy in the treatment of knee OA [14, 15]. Moreover, this therapy is conditioned by a power placebo effect due to the presence of the machine and of the therapist applying the treatment.

Finally, tolerability seemed to be excellent for short wave therapy and good for spa therapy, with light and transitory side effects.

Our study aimed to verify the efficacy of two therapeutic modalities utilized according to classic treatment models for [7, 14]: spa therapy and short wave therapy. Spa therapy demonstrated an efficacy persistent over time, probably in relationship to its mechanism of action, not only due to temperature, but also to the specific effects of its mineral content.

On the contrary, short wave therapy demonstrated only a short-term symptomatic efficacy.

In conclusion, our study highlighted the superiority of arsenical ferruginous spa therapy compared to short wave therapy, and it confirmed the symptomatic efficacy of spa therapy, already shown by other authors, in the treatment of gonarthrosis.

Further studies are necessary on large case histories with different types of mineral waters and with long-term follow-ups in order to verify the real persistence over time of the therapeutic efficacy of spa therapy.

References

Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al (1998) Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in US. Arthritis Rheum 41:778–799

Garcia Rodriguez LA, Hernandez-Diaz S (2001) The risk of upper gastrointestinal complications associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, acetaminophen, and combination of these agents. Arthritis Res 3:98–101

Perlman AI, Eisenberg DM, Panush RS (1999) Talking with patients about alternative and complementary medicine. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 25:815–822

Szucs L, Ratko I, Lesko T, Szoor I, Genti G, Balint G (1989) Double-blind trial on the effectiveness of the Puspokladany thermal water on arthrosis of the knee joints. J R Soc Health 109:7–9

Sukenik S, Buskila D, Neumann L, Kleiner-Baumgarten A, Zimlichman S, Horowitz J (1990) Sulphur baths and mud pack treatment for rheumatoid arthritis at the dead sea area. Ann Rheum Dis 49:99–102

Wigler I, Elkayam O, Paran D, Yaron M (1995) Spa therapy for gonarthrosis: a prospective study. Rheumatol Int 15:65–68

Nguyen M, Revel M, Dougados M (1997) Prolonged effects of 3 week therapy in a spa resort on lumbar spine, knee and hip osteoarthritis: follow-up after 6 months. A randomized controlled trial. Br J Rheumatol 36:77–81

Neumann L, Sukenik S, Bolotin A et al (2001) The effect of balneotherapy at the dead sea on the quality of life of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 20:15–19

vanTubergen A, Landewe R, van der Heijde D et al (2001) Combined spa-exercise therapy is effective in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 45:430–438

Flusser D, Abu-Shakra M, Friger M (2002) Therapy with mud compresses for knee osteoarthritis: comparison of natural mud preparation with mineral depleted mud. J Clin Rheumatol 8:197–203

Kovacs I, Bender T (2002) The therapeutic effects of Cserkeszolo thermal water in osteoarthritis of the knee: a double blind, controlled, follow-up study. Rheumatol Int 21:218–221

Sukenik S, Flusser D, Abu-Shakra M (1999) The role of spa therapy in various rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 25:883–897

Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, Kessels AG, Boers M, Knipschild PG. Balneotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD000518

Moffet JA, Richardson PH, Frost H, Osborn A (1996) A placebo controlled double blind trial to evaluate the effectiveness of pulsed short wave therapy for osteoarthritic hip and knee pain. Pain 67:121–127

Shields N, Gormley J, O’Hare N (2002) Short wave diathermy: current clinical and safety practices. Physiother Res Int 7:191–202

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al (1986) Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee diagnostic and therapeutic criteria committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum 29:1039–1049

Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS (1957) Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 16:494–502

Lequesne MG, Mery C, Samson M, Gerard P (1987) Indexes of severity for osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Validation-value in comparison with other assessment tests. Scand J Rheumatol [Suppl 65]:85–89

Meenan RF, Gertman PM, Mason JH (1980) Measuring health status in arthritis. The arthritis impact measurement scales. Arthritis Rheum 23:146–152

Salaffi F, Cavalieri F, Nolli M, Ferraccioli G (1991) Analysis of disability in knee osteoarthritis. Relationship with age and psychological variables but not with the radiographic score. J Rheumatol 18:1581–1586

Dougados M, Nguyen M, Listrat V, Amor B (1989) Score d’ équivalence des AINS (abstract 1134). Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic 56:251

Guillemin F, Virion JM, Escudier P, De Talance N, Weryha G (2001) Effect on osteoarthritis of spa therapy at Bourbonne-les-Bains. Joint Bone Spine 68:499–503

Fioravanti A, Bisogno S, Nerucci F, Cicero MR, Locunsolo S, Marcolongo R (2000) Evaluation of the efficacy and tolerance of radioactive fangotherapy in gonarthrosis. Comparative study versus short wave therapy. Minerva Med 91:291–298

Cozzi F, Lazzarin P, Todesco S, Cima L (1995) Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation in healthy subjects undergoing mud-bath applications. Arthritis Rheum 38:724–726

Bellometti S, Galzigna L (1998) Serum levels of a prostaglandin and a leukotriene after thermal mud pack therapy. J Investig Med 46:140–145

Bellometti S, Cecchettin M, Galzigna L (1997) Mud pack therapy in osteoarthrosis. Changes in serum levels of chondrocyte markers. Clin Chim Acta 268:101–106

Bellometti S, Galzigna L, Richelmi P, Gregotti C, Berté F (2002) Both serum receptors of tumor necrosis factor are influenced by mud pack treatment in osteoarthrotic patients. Int J Tissue React 24:57–64

Bellometti S, Richelmi P, Tassoni T, Berté F (2005) Production of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in osteoarthritic patients undergoing mud bath therapy. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 25:77–94

Bellometti S, Cecchettin M, Lalli A, Galzigna L (1996) Mud pack treatment increases serum antioxidant defenses in osteoarthrosic patients. Biomed Pharmacother 50:37

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Colleen Connell for her assistance with the translation of the text.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cantarini, L., Leo, G., Giannitti, C. et al. Therapeutic effect of spa therapy and short wave therapy in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, single blind, controlled trial. Rheumatol Int 27, 523–529 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-006-0266-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-006-0266-5