Summary

This chapter deals with some taxonomic and ecological aspects of picocyanobacteria (Pcy) single-cells, microcolonies and other colonial (CPcy), that are common in lakes throughout the world, and abundant across a wide spectrum of trophic conditions. We discussed phenotypic diversity of Pcy in conjunction with a genotypic approach in order to resolve whether a similar morphology also reflects a phylogenetic relationship. Microcolonies of different size (from 5 to 50 cells) constitute a gradient without a net separation from single-celled types and should be considered Pcy, as transition forms from single-cell to colonial morphotypes. The single-celled Pcy populations tend to be predominant in large, deep oligo-mesotrophic lakes, while the CPcy find optimal conditions in warmer, shallower and more nutrient rich lakes. The knowledge of Pcy diversity in pelagic and littoral zone habitats is a key to understand the dominance of certain genotypes in the water column and of their ubiquity. We devoted some paragraphs to analyse the factors (biotic and abiotic) which can influence the dynamics of the different Pcy forms and we have approached the study of their common ecology.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Cyanobacterial Bloom

- Oligotrophic Lake

- Dissolve Organic Phosphorus

- Deep Chlorophyll Maximum

- Synechococcus Strain

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

A phylogenomic study of the evolution of cyanobacterial traits shows that the earliest lineages were probably unicellular cells in terrestrial and/or freshwater environments (Sánchez-Baracaldo et al. 2005; Blank and Sánchez-Baracaldo 2010) rather than in the marine habitat as suggested by Honda et al. (1999). This discovery opens new prospects for the study of freshwater Pcy and provides an impetus for phylogenetic and ecological investigations to clarify the many uncertainties in the literature. One of the most striking differences between freshwater and marine Pcy lies in the extraordinary richness of morphotypes and the unresolved phylogeny of Pcy in lakes. However, despite marked phylogenetic differences, Pcy have a similar pattern in their absolute and relative importance in freshwater and marine systems along the trophic gradient (Bell and Kalff 2001).

This chapter discusses freshwater Pcy single-cells together with microcolonies and other colonial forms, that are common in lakes throughout the world (Hawley and Whitton 1991a) and abundant across a wide spectrum of trophic conditions. Though their abundance in meso-eutrophic lakes is often high enough to reduce transparency and cause water discolouration, they seldom create the blooms associated with larger colonial cyanobacteria. Although studies of the ecology of microcolonies and colonial forms are few, there have been sufficient studies within the past 25 year of Pcy in lakes and their role in food webs to warrant synthesis and further review (Stockner et al. 2000; Callieri 2008).

The picocyanobacteria exhibit two common morphologies: single cells (coccoid, rods) and colonies with diverse colonial morphology. We propose here to consider microcolonies as transitional forms from single cells to colonial morphotypes (Fig. 8.1). Under favourable conditions some Pcy can develop mucilage or a sheath and remain near to the mother cell forming a clump. Here we designate as picocyanobacteria (Pcy) the single cells (0.2–2.0 μm) which are the major component of the picophytoplankton community, and as colonial picocyanobacteria (CPcy) all species whose predominant morph is colonial and have single cells ranging from 0.5 to 3.0 μm. Microcolonies of different size (from 5 to 50 cells) constitute a gradient without a clear separation from the single-celled type and should be considered Pcy.

Until the past few decades most research on Pcy focused on the CPcy, because their colonies were easily seen by conventional microscopy, and their ubiquity in meso-eutrophic lakes of Northern Europe attracted the attention of early descriptive taxonomists (Lemmermann 1904; Naumann 1924; Skuja 1948). CPcy also seem to have received more thorough systematic descriptions, along with some comment on habitat preference and distribution (Komárek 1958, 1996; Cronberg 1991; Komárková-Legnerová and Cronberg 1994).

The emergence of Pcy as an important research topic for limnologists and oceanographers provides an opportunity to discuss to what extent this large and diverse group share a common ecology. The current challenge is to understand better the relationship between the diversity and ecology of Pcy, microcolonies and CPcy and their interaction with the environmental factors that allow the proliferation of the most competitive genotypes. The study of genome divergence, lateral gene transfer and genomic islands will provide new opportunities for a better understanding of niche adaptation (Dufresne et al. 2008; Scanlan et al. 2009 and Chap. 20). We conclude this review with a plea for limnologists to pay more attention to these organisms. Their extent and abundance in lakes may provide an important message about the changes likely to occur in pelagic community structure in the warmer world expected in the near future (Mann 1993; Stockner 1998).

2 Taxonomy and Phylogenetic Diversity

2.1 Single Cells and Microcolonies

Even more than for most prokaryotes the morphological features of Pcy are insufficiently distinct to provide a reliable basis for discriminating taxa (Staley 1997; Komárek et al. 2004). The criteria for the definition of genera of single-celled Pcy such as Cyanobium, Synechococcus and Cyanothece dianae/cedrorum-type (Komárek 1996) have been supplanted by molecular methods which focus on clade divergence in the phylogenetic tree rather than on morphological differences. The clade containing Pcy (Synechococcus/Prochlorococcus/Cyanobium sensu Sánchez-Baracaldo et al. 2005) is formed by coccoid and rod-shaped cells with a diameter <3 μm. Analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) of freshwater Synechococcus shows it is a polyphyletic genus and cannot be considered a natural taxon (Urbach et al. 1998; Robertson et al. 2001). In the phylogenetic tree the Antarctic strains represent a unique and highly adapted clade related only peripherally to Synechococcus sp. (Cluster 5.2, Marine Cluster B) (Vincent et al. 2000; Powell et al. 2005).

It has become increasingly clear that phenotypic diversity should be evaluated in conjunction with genotypic analysis in order to resolve whether a similar morphology also reflects a phylogenetic relationship (Wilmotte and Golubić 1991). Even though many genetically distinct Synechococcus strains have been found (Robertson et al. 2001), it is still helpful to classify Pcy into two cell types: the first with yellow autofluorescing phycoerythrin (PE-rich cells), and the second with red autofluorescing phycocyanin (PC-rich cells) as the major light-harvesting pigment (Fig. 8.2) (Wood et al. 1985; Ernst 1991). Phycoerythrin-rich strains have an absorption peak at ∼560 nm, and hence absorb green light effectively. Phycocyanin-rich strains have an absorption peak at ∼625 nm, and absorb orange-red light effectively (Callieri et al. 1996a ; Haverkamp et al. 2008).

Phylogenetic studies have mostly been performed using sequence data derived from 16S rDNA which is a conserved gene, but shows high pair-wise similarity in freshwater Pcy (Fig. 8.3, Crosbie et al. 2003a) and cannot resolve the actual genetic variation that accompanies their physiological diversity (Urbach et al. 1998). Less conserved genetic markers can offer a more detailed definition of the diversity of Pcy (Haverkamp et al. 2009). In particular the spacer between the 16S and 23S rDNA (ITS-1) exhibits a great deal of length and sequence variation and can be used to differentiate marine and freshwater Pcy ecotypes using fingerprinting techniques (T-RFLP, DGGE or ARISA) (Rocap et al. 2002; Becker et al. 2002; Ernst et al. 2003). In a glacial Andean lake system (Argentina) the ARISA showed habitat specificity of some Pcy OTU, emphasizing the microdiversity due to geographical barriers (Caravati et al. 2010). Similarly, the study of functional genes as, for example, those encoding for phycocyanin and phycoerythrin (cpcBA and cpeBA) can offer another perspective on the evolution of Pcy, grouping the strains on the basis of pigment composition (Haverkamp et al. 2008; Jasser et al. 2011). Indeed, it has been found that phylogenies based on phycobiliprotein rod gene components are not congruent with the 16S rRNA phylogeny whilst those based on the allophycocyanin core are congruent (Six et al. 2007; Haverkamp et al. 2009). This is explained by the presence of phycobilisome rod components within genomic islands that potentially allow their transfer between Synechococcus lineages (Six et al. 2007). A comparison of marine Synechococcus showed that their adaptation to different ecological niches can be related to the variable number of horizontally acquired genes located in highly variable genomic islands (Dufresne et al. 2008). Similar to what happens in Prochlorococcus (Coleman et al. 2006); it is likely that phages carrying host genes can mediate lateral gene transfer. This discovery opens new perspectives to the understanding of the local adaptation and the definition of species within the Synechococcus group.

The phylogenetic approach combined with RT-qPCR has been used to assess Pcy in both marine (Ahlgren et al. 2006) and freshwater community structure (Becker et al. 2000, 2007). Using small subunit (ssu) rDNA sequences from novel culture isolates together with environmental samples from the Baltic Sea and seven freshwater lakes, Sánchez-Baracaldo et al. (2008) showed that freshwater Pcy communities encompass much greater diversity than is found in marine systems. They hypothesised a more rapid speciation in lakes allowed by geographical barriers and noticed that most of the sequences from the Baltic Sea were related closely to freshwater lineages.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of SSU rDNA sequences from unicellular picocyanobacteria, (green circle: PC-rich, pink circle: PE-rich) (For details see Crosbie et al. 2003a, reproduced with permission)

To provide a more realistic phylogenetic tree of cyanobacteria Sánchez-Baracaldo et al. (2005) used a combination of different molecular sequence data instead of individual genes. Flanking a selection of morphological traits into the backbone cyanobacterial tree they showed that the ancestral cyanobacterium were a single cell and that filamentous/colonial forms appeared later in time. The presence of a well-defined sheath, associated with the colonial lifestyle, is a trait which has been lost and attained several times during evolution. In Arctic lakes the Pcy strains isolated appear to be closely related to Microcystis elabens (Vincent et al. 2000) now reclassified as a species of Aphanothece (Komárek and Anagnostidis 1999). Thus, it is tempting to suggest that microcolonies, which are frequently found in freshwater, may be considered transition forms from single cells to true colonial. In this sense the investigations done by Crosbie et al. (2003a) confirm the existence of single cell/single colony strains, with different degrees of aggregation, possibly belonging to the group H and group B subalpine cluster I.

2.2 Colonies

Most of the small pico-cell-sized CPcy belong to the chroococcal cyanobacteria. The cell size ranges between 0.5 and 3 μm in diameter and the cell form is generally spherical, ovoid or rodlike. The cells occur in colonies of different morphology and these colonial morphologies are often species specific, and can be used in discriminating species. The cells inside the CPcy colony can be loosely or densely packed, or can form pseudo-filaments or other net-like structures. In some species the cells are attached to mucilaginous stalks, which are centred in the middle of the colony (e.g. Cyanonephron, Snowella). In lakes where CPcy are common, there is usually a mixture of species each with distinctive colony structure, which are quite readily identifiable. CPcy are found throughout the entire spectrum of lake trophic conditions; however most tend to occur in more productive meso-eutrophic lakes. Some of the most common CPcy in fresh waters are species belonging to the genera Aphanocapsa, Aphanothece, Chroococcus, Coelosphaerium, Cyanobion, Cyanodictium, Merismopedia, Romeria, Snowella and Tetracercus (Table 8.1).

There are few records of the development of CPcy in nature or in culture and accordingly the available literature is sparse. The CPcy are only a small component in water blooms and are thus often overlooked and usually neglected. Due to their minute cell size, unfiltered samples must be taken from lakes, as the CPcy will otherwise pass through the meshes of normal plankton nets (mesh width 10–45 μm) and are lost. The colonies of CPcy are normally counted in sedimentation chambers under 400–1,000× magnification. The settling time of CPcy must be long; for example in a 5 cm long chamber the settling time should be about 4 days and nights and the sample must be well preserved in Lugol’s solution.

Bláha and Marsálek (1999) isolated seven strains of Pcy from water blooms in the Czech Republic and tested their ability to produce toxins. They found that two strains produced the hepatotoxin microcystin. As most all Pcy can readily pass through the filters in drinking water treatment plants, they cannot be neglected and as possible sources of toxins should be carefully monitored.

Several studies of cyanobacteria within Brazil’s drinking water reservoirs have been made and provide an overview of their current status (Domingos et al. 1999; Komárek et al. 2001; Sant’Anna et al. 2004; Furtado et al. 2009). As most of the reservoirs were dominated by cyanobacteria, it was important to assess for cyanobacterial toxicity. Cyanobacteria, including CPcy and Pcy were isolated and tested for algal toxins with HPLC and/or ELISA methods. Several cyanobacteria including CPcy were found to be toxic; for example Aphanocapsa cumulus from Caruaru Reservoirs, where several persons have died after having dialysis with drinking water from these reservoirs (Domingos et al. 1999). In Tabocas reservoir CPcy were also very frequent and strains were isolated, e.g. Aphanocapsa cumulus, Aphanothece stratus, and a new species Romeria carauru was recorded (Komárek et al. 2001). No toxin tests were made on these species, thus it was not confirmed whether these species were responsible for the Carauro (Komárek et al. 2001), but they likely were. The morphology of strains of A. stratus and Cyanobium-like Pcy were studied with TEM, and their morphologies were identical and they evidently belonged to the same species. During the life-cycle A. stratus lived in colonies in the benthos, but as single cells or microcolonies in the plankton (Komárek et al. 2001). Pairwise similarities 16S rDNA sequence of A. stratus, R. carauru and other related cyanobacterial strains were carried out, but further studies are needed to evaluate genotype resemblance.

Furtado et al. (2009) studied cyanobacteria in waste stabilization pond systems in Brazil and recorded several CPcy. Morphological identification and phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rDNA sequence were made on the isolated strains and a phylogenetic tree with related species was obtained. They noted that the strains Synchococcus CENA 108 and Merismopedia CENA 206 were both capable of producing microcystins at large population densities (>1 × 106 cells mL−1, Furtado et al. 2009).

3 A Common Ecology?

3.1 Single Cell and Microcolony Dynamics

Sufficient information is now available to define the different patterns of Pcy, single-cells and microcolonies, in lakes of different size, thermal regime and trophic state (Callieri 2008, 2010). In lakes of temperate regions maxima generally conform to a typical bimodal pattern, with a spring or early summer peak and a second peak during summer-autumn (Stockner et al. 2000). This is the case of most of the subalpine large lakes without ice-cover e.g. Lake Maggiore, Lake Constance, but also for Lake Stechlin, a deep oligo-mesotrophic lake in the Baltic Lake District where ice-cover occurs (Padisák et al. 2003). However looking at the long-term series of Pcy abundance in Lake Maggiore (Fig. 8.4) (Callieri and Piscia 2002), Lake Constance (Gaedke and Weisse 1998), and Lake Stechlin (Padisák et al. 2003) not all the years are clearly bimodal. The great interannual variability of Pcy dynamics is mainly related to differences in weather conditions which cause different spring mixing regimes and timing of water column stabilization (Weisse 1993). Studies in British Columbia’s temperate oligotrophic lakes have shown a clear trend in both magnitude and timing of Pcy seasonal maxima related to levels and duration of seasonal nutrient supplementation (Stockner and Shortreed 1988, 1994).

Large spring peaks are also common in eutrophic, hypereutrophic and dystrophic shallow lakes (Sime-Ngando 1995; Jasser 1997; Mózes et al. 2006). The seasonal patterns found in Danish lakes (Søndergaard 1991), Canadian lakes (Pick and Agbeti 1991), Lake Biwa, Japan (Maeda et al. 1992), English lakes (Hawley and Whitton 1991b; Sánchez-Baracaldo et al. 2008), Lake Mondsee, Austria (Crosbie et al. 2003c), Lakes Bourget and Geneva, France (Personnic et al. 2009a) all lack the spring peak, there being only a summer or autumn maximum. The lack of Pcy spring peak in these was probably due to weak stratification in March-April and hence relatively deep vertical mixing. This interpretation is strengthened by studies on Lake Baikal, where owing to winter ice cover and extended spring isothermal conditions, Pcy reach high abundance only in summer months and lack a spring peak (Belykh et al. 2006).

In Arctic and Antarctic lakes Pcy are widely distributed, despite the fact they are generally present in low abundance in the marine polar environment (Vincent 2000; Chap. 13). In continental Antarctica in meromictic saline Ace Lake Pcy reached concentrations one order of magnitude higher than in temperate lakes in summer – 8 × 106 cells mL−1 (Vincent 2000). In the Antarctic Peninsula in Lake Boeckella (Izaguirre et al. 2003) Pcy abundance was as high as 3.6 × 105 cells mL−1 and represented up to 80% of phytoplankton biomass (Allende and Izaguirre 2003). However very low Pcy concentrations (102–103 cells mL−1) were recorded in a set of shallow lakes and ponds in the Byers peninsula of maritime Antarctica (Toro et al. 2007). In contrast to all these, tropical lakes show high cell numbers (105–106 cell mL−1) throughout the season with higher early-spring peaks (Peštová et al. 2008) or summer peaks (Malinsky-Rushansky et al. 1995), depending upon the interactions of Pcy with other phytoplankton.

In Lake Maggiore the pronounced late summer peak of Pcy is composed by different morphotypes, including microcolonies (Passoni and Callieri 2000) (Fig. 8.5). Microcolonies are generally present throughout the euphotic zone, albeit in low abundance in all oligotrophic lakes, e.g. representing around 25% of the single-cell forms in Lake Maggiore (Passoni and Callieri 2000). The peak abundance of Pcy microcolonies appears in summer or autumn in a variety of freshwater systems (Fahnenstiel and Carrick 1992; Klut and Stockner 1991; Komárková 2002; Szelag-Wasielewska 2003; Crosbie et al. 2003c; Mózes et al. 2006; Ivanikova et al. 2007). Such a variety of morphotypes reflects a genotypic diversity among Pcy communities that accounts for the different Pcy patterns of morphotype composition observed in spring and summer assemblages (Callieri et al. 2007; Callieri et al. 2012: Fig. 8.6). Using RT-qPCR, a type of rapid succession of individual clades of Pcy illustrates the patchy structure of the Pcy community over quite small spatial/temporal scales (Sánchez-Baracaldo et al. 2008). At the same time the co-existence of genetically and physiologically diverse Synechococcus spp. found in the pelagic zone of Lake Constance indicates the possible niche partitioning exploited by the different strains (Postius and Ernst 1999; Ernst et al. 2003). In Lake Maggiore the vertical partitioning of Pcy OTUs down the water column was more evident during summer stratification (Callieri et al. 2012). In marine systems distinct Pcy lineages have also been shown to partition between waters having different environmental characteristics; a feature evident over large spatial scales (Fuller et al. 2006; Zwirglmaier et al. 2007, 2008). In the Sargasso Sea the community composition of Pcy varied during the season with the highest numbers of Synechococcus in spring and Prochlorococcus in summer and autumn (DuRand et al. 2001). We suggest that the new perspective of habitat-related distribution pattern of Synechococcus proposed for Lake Constance (Becker et al. 2007) and Lake Maggiore (Callieri et al. 2012) could be generalized to other aquatic systems as well.

Seasonal changes of single-cell picocyanobacteria, microcolonies and colonial coccoid cyanobacteria (mainly Aphanothece clathrata, A. cf. floccosa and Microcystis sp.) abundance in Lake Maggiore (from Passoni and Callieri 2000, modified)

Moreover, there is strong evidence that Pcy of the cyanobacterial evolutionary lineage VI sensu Honda et al. (1999) are not exclusively pelagic, but can also inhabit periphytic biofilm in the euphotic zone of temperate lakes (Becker et al. 2004). We should integrate our knowledge of Pcy diversity in pelagic and littoral zone habitats to better explain the dominance of certain genotypes in the water column, because the adaptability of these microorganisms may well be the key feature that accounts for their ubiquity (Becker et al. 2004).

Studies of the vertical distribution of populations of Pcy have provided important information about their response to changing physical and biological variables within the euphotic zone. Though Pcy cells are small and their settling rate negligible, their abundance and distribution within the water column can change rapidly with different thermal and light regimes, and to the presence of predators or viruses (Pernthaler et al. 1996; Mühling et al. 2005). Water column depth, which is often inversely related to the trophic state of the lake, is an important indicator of the presence of Pcy and/or of its abundance relative to larger species of phytoplankton. Deep, clear oligotrophic lakes typically support Pcy comprising mainly PE-rich cells; conversely in shallow, turbid lakes PC-rich cells prevail (Callieri and Stockner 2002). This disparity in the distribution of PE- and PC-rich cells is due to their characteristic spectral signature (Everroad and Wood 2006), which has been associated with particular underwater light quality (Hauschild et al. 1991; Vörös et al. 1998). In North Patagonian, in which blue light dominate the underwater light climate, Pérez et al. (2002) found that PE-rich cells typically dominate the Pcy forming a deep chlorophyll maxima (DCM) at the base of the euphotic zone (Callieri et al. 2007; Fig. 8.7). In Lake Baikal at offshore stations the Pcy are mainly PE-rich cells, whereas PC-rich cells are found at near-shore stations (Katano et al. 2005, 2008), suggesting the occurrence of water quality differences in various zones of the lake. Similar situations have been described for Lake Balaton where in the eastern basin PE-rich cells dominate, while in the western basin PC-rich cells are dominant (Mózes et al. 2006). It is the establishment of a pronounced thermocline at depth which likely favours the development of DCM, largely made up of Pcy which are suited both to low nutrient and light conditions (Modenutti and Balseiro 2002; Gervais et al. 1997; Camacho et al. 2003; Callieri et al. 2007). In Lake Tahoe Pcy dominated in the nutrient deficient upper water column during the stratified season, in a distinct vertical niche with respect to picoeukaryotes which peaked at the DCM (Winder 2009), similar to patterns found in the Oceans (Vázquez-Domínguez et al. 2008). The dynamics of DCM formed by Pcy is quite unstable and its duration is unpredictable, depending upon the strength of hydrodynamic field and biotic interactions. A good example is provided by Pcy communities in Lake Maggiore where DCM can appear, and also suddenly disappear, in just a few days (Fig. 8.8). Further, it has been shown that the interaction of different biotic and abiotic factors within the water column can affect Pcy vertical distribution patterns, with peaks of abundance in the lower metalimnion and upper hypolimnion of Lakes Huron and Michigan (Fahnenstiel and Carrick 1992); in Lake Stechlin (Padisák et al. 1998, 2003); in the metalimnion, beneath the steepest part of the thermocline, in Lake Constance and Lake Maggiore (Weisse and Schweizer 1991; Callieri and Pinolini 1995); in the metalimnion of Lake Baikal (Nagata et al. 1994); and in the epilimnion of Lake Biwa (Maeda et al. 1992), Lake Kinneret (Malinsky-Rushansky et al. 1995) and Lake Alchichica, Mexico (Peštová et al. 2008).

Vertical distribution of Pcy cells in the water column of six ultra-oligotrophic lakes of northern Patagonia, Argentina (Callieri et al. 2007, modified) PAR: Photosynthetically Active Radiation

Six vertical profiles of Pcy abundance, temperature and PAR in Lake Maggiore, during 30 days of summer stratification (C. Callieri and L. Oboti unpublished data). PAR shown in blue and temperature in red line; Pcy abundance shown with histograms: the black ones indicate the Pcy abundance at the depth of thermocline and the yellow ones the abundance at the other depths

3.2 Colony Dynamics

Although colonial picocyanobacteria (CPcy) are common in meso- to eutrophic lakes, there are few publications about their life-history and ecology. CPcy are “metaphyton” that often appear in the euphotic zone as plankton, but their origins are associated with the littoral and deeper benthos communities. They occur in most cyanobacterial blooms together with larger and more common cyanobacteria like Microcystis, Aphanizomenon and Anabaena. In most cases the CPcy only constitute a small percentage of the total colonial cyanobacteria biomass of the plankton; nevertheless CPcy species alone can also form heavy blooms (Cronberg 1999).

In Sweden monitoring programs for lake water quality started in the 1970s and in some cases continues today with a focus on phytoplankton and water chemistry. A classic case is Lake Trummen, in central south Sweden that was very eutrophic, but was restored to a lower production status in 1970 by dredging and removal of 0.5 m nutrient-rich sediment (Björk et al. 1972). After dredging lake water quality consistently improved and the cyanobacterial blooms diminished both in size and duration. In spring 1975 Lake Trummen was invaded by a large number of small bream and roach from nearby Lake Växjösjön and in consequence the predation of fish on zooplankton was extremely heavy. All cladocerans disappeared and a dense water bloom of the CPcy Cyanodictyon imperfectum (now called Cyanocatena imperfectum, Fig. 8.9), appeared reaching peak densities in September that constituted 95% of the total cyanobacterial bloom. The summer of 1975 was very warm and dry creating optimal conditions that likely contributed to the heavy CPcy bloom (Cronberg and Weibull 1981), some photos of which are shown in Fig. 8.10.

Lake Ringsjön, situated in central Scania, Sweden, consists of three basins and is one of the largest lakes in the region. The three basins have been monitored since 1982 and CPcy frequently occur in varying population densities (Fig. 8.11). In Lake Ringsjön dense algal blooms have been observed during the summer, and this lake, like Lake Trummen, also had a large population of small bream, roach and perch. During 2005–2009 Lake Ringsjön western basin was biomanipulated and small cyprinid fish were removed, which resulted in a slight reduction of phytoplankton biomass (Bergman et al. 1999). However, the CPcy increased in the beginning of the period suggesting that fish reduction in some way affected CPcy production. The cyanobacterial community was dominated by species of the genera Microcystis, Aphanizomenon, Anabaena and Woronichinia. CPcy consisted mostly of Aphanocapsa delicatissima, Aphanothece clathrata, A. minutissima and Cyanodictyon imperfectum (Cronberg 1999).

In the late 1990s park ponds in the city of Malmö, southern Sweden, were studied owing to outbreaks of heavy cyanobacterial blooms that sometimes caused large bird kills. These cyanobacterial blooms consisted of species of Microcystis, Aphanizomenon, Anabaena, Anabaenopsis, and sometimes also of CPcy in high densities. In 1995 a toxic bloom of Cyanobion bacillare appeared in the Large Slottspark Pond in Malmö and during July and August about 650 water fowl, mainly mallard ducks, died (Fig. 8.12). In late August water was analyzed for algal toxins and showed high concentrations of microcystin, about 86 μg L−1, and biopsies on several dead birds showed severe damage to the liver and kidney; injuries typical of the toxin microcystin (Cronberg, unpublished data). A few years later, in 2000, the Middle Öresund Pond in Malmö exhibited an algal bloom of another CPcy species, which was a “new” CPcy species to phycological science – Cyanodictyon balticum (Cronberg 2003). C. balticum appeared from June to October with maximal development in September (Fig. 8.13). During the bloom period, the zooplankton population was also monitored, and in August, when the zooplankton declined, the CPcy increased. As long as zooplankton were present C. balticum biomass was kept low, but increased substantially when zooplankton disappeared. Among zooplankters, the rotifers in particular seemed to feed preferentially on the CPcy.

C. balticum is a frequent phytoplankter in the Baltic Sea where several different CPcy species are common, and they are also common in lakes in the surrounding countries. They appear in shallow meso-, eutrophic- to hypertrophic lakes and ponds where they live as part of the metaphyton on the lake bottom; but as a result of wind and convective mixing they often become distributed in the pelagic zone and become part of the plankton community (Komárek et al. 2001). Meterological and hydrological conditions doubtless play an important role in the distribution of CPcy. The composition of the surrounding soil and ground water; the presence of anaerobic littoral sediments and attendant nutrient release; even at a slightly elevated salinity, each can either alone or collectively influence the physico-chemical conditions in littoral-benthic water, and create more optimal conditions for CPcy development.

As CPcy are sometimes major components of the pelagic phytoplankton community they are influenced not only by the available nutrients, but also by other planktonic organisms. The grazing by zooplankton and by heterotrophic flagellates may reduce the number of CPcy, and the presence of small fish may also influence the CPcy populations. Furthermore, some CPcy have the ability to produce toxins, so if CPcy colonies are disrupted during the treatment process for drinking water, potentially they can affect human health.

3.3 Single Cells Versus Microcolonies

There is a growing interest in the relationship between the status of Pcy microcolonies in a lake and the trophic state of that lake (Callieri 2010). It has been suggested that the abundance of microcolonies in temperate lakes in mid-summer, when nutrients are likely to be depleted may reflect more efficient nutrient recycling, with the colonies providing a self-sustaining microcosm that offers a competitive advantage over single cells (Klut and Stockner 1991). However, Crosbie et al. (2003c) considered this hypothesis unlikely for Pcy (Crosbie et al. 2003c) in view of results for colony-forming marine alga Phaeocystis, where the boundary layer can strongly limit nutrient diffusion into the colonies (Ploug et al. 1999). At low phosphorus concentrations the colonial forms grow slower than the single-cell forms (Veldhuis and Admiral 1987), presumably due to the lower cell-specific nutrient fluxes in colonies (Ploug et al. 1999). But in microcolonies, formed by 5–10 cells in one plane, the duplication should not be depressed as much as in a large, thick colony, where the diffusion of nutrients is impeded. In this case, exudates adsorbed to the cell surface can act as rich metabolite pools (Klut and Stockner 1991). Therefore, during the initial stage of their formation a microcolony can have a selective advantage in nutrient depleted ecosystems.

Crosbie et al. (2003c) observed an increase of microcolonies in nutrient-poor surface waters in Lake Mondsee and attributed their formation to the production of photosynthate-rich mucilage in Pcy single-cells that were actively photosynthesising organic carbon. As the leakage or excretion of photosynthate has been considered one protection mechanism against photochemical damage (Wood and van Valen 1990), it is likely to also consider the effect of irradiance (PAR and UVR), at near-surface depths, as a stressor promoting clumping of daughter cells during duplication (Fig. 8.14).

To better understand genus-specific microcolony formation one must consider the factors influencing cell aggregation, despite the many differences between microcolonies and aggregates. The results by Koblížek et al. (2000) suggest that in culture Synechococcus elongatus aggregates rapidly if exposed to blue light (30 min, 1,000 μmol photon m−2 s−1) owing to the effect of electron transfer downstream of PSI, with reactive oxygen radicals (ROS) probably triggering the aggregation. PSI therefore may have an important role in the first stages of microcolony formation in lakes. The influence of moderate UVR on microcolony formation was tested on PE- and PC-rich Synechococcus cultures (Callieri et al. 2011). Previous acclimation to low or moderate PAR influences the strain response, mainly due to carotenoid content in the cell. In general microcolony formation appears as a defence strategy of the low acclimated culture (Callieri et al. 2011).

As well as cell metabolism alterations caused by external factors such as light, other important structural changes of Pcy single-cells must be mentioned as a causative factor inducing microcolony formation. Aggregation is an ATP-independent process without any de novo protein synthesis (Koblížek et al. 2000), and this indicates that some structures responsible for the aggregation must be present on the cell surface before irradiation. For example, in selected strains with different genotypes isolated from Lake Constance; Ernst et al. (1996) found that they possess a surface S-layer composed of regularly ordered globular protein layers that would facilitate colony formation. Also, in grazing (by Ochromonas sp.) induced microcolonies of PC-rich Cyanobium sp., rigid tubes from 100 nm to 1 μm long (spinae) have been observed on the cell surface (Jezberová and Komárková 2007). To what extent the formation of microcolonies is due to the presence of specific Synechococcus or Cyanobium genotypes or is the result of a specific survival strategy (Ernst et al. 1999; Passoni and Callieri 2000) needs further clarification. Unicellular Microcystis aeruginosa Kützing, when exposed to Ochromonas sp. grazing, increased the diameter of the colonies and the extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) content (Yang and Kong 2012).

A fascinating hypothesis on microcolony formation is related to the observation by Postius and Böger (1998) that exo-polysaccharides exudated by Pcy as microzones for diazotrophic bacteria growth may affect microcolony formation. This finding opens new perspectives for the study of consortial, synergistic interactions that may be of critical importance to our understanding of colony formation in Pcy.

3.4 Growth Rate and Occurrence Along the Trophic Gradient

The processes of cell growth and division in all the photosynthetic organisms are as tightly coupled as photosynthesis and growth rate, and are light dependent (Kana and Glibert 1987a, b; Chisholm et al. 1986). In Pcy there is little difference between marine and freshwater strains of Synechococcus in both cell division and growth, with cell division reaching a maximum in the afternoon, triggering an increase in cell number that proceeds in the dark (Chisholm et al. 1986; Callieri et al. 1996 b; Jacquet et al. 2001). These light/dark cycles produce rhythmic cell divisions that are related to growth rate and photosynthetic activity and are driven by prevailing light conditions. Experimental laboratory evidence of the influence of light on growth rate is well documented by Fahnenstiel et al. (1991) for freshwater Synechococcus strains and by Campbell and Carpenter (1986a) for marine strains. These investigators have measured growth rates at light intensities up to 75 and 120 μmol photon m−2 s−1 that simulate natural irradiance levels. Kana and Glibert (1987b) have extended the light intensity limit up to 2,000 μmol m−2 s−1, demonstrating that growth rate becomes light saturated at 200 μmol m−2 s−1; however Synechococcus has a mechanism of photo-adaptation which permits cell growth and photosynthetic activity to continue at higher irradiances. Moser et al. (2009) have shown that growth rates of three Pcy strains of different pigment composition (PE-rich and PC-rich strains) and phylogenetic positions differed widely in response to light intensity and photo-acclimation (Fig. 8.15). Their results show that freshwater Pcy possess the ability of photo-adaptation, but the extent of photo-adaptation depends on the duration of photo-acclimation, and is strain-specific.

Growth rates of picocyanobacterial strains at 9 different irradiances after 2 months acclimation to 10 μmol photon m-2 s-1 (left) and 100 μmol photon m-2 s-1 (right). MW4C3 = PE-strain Group B; MW100C3 = PC-strain Group I; BO8801 = PC-strain Group A Cyanobium. The growth response at high light of the two PC-strains acclimated at 100 µmol photon m-2 s-1 shows the importance of ribotype cluster membership (From Moser et al. 2009)

Other environmental conditions such as nutrient concentration and temperature can affect cell specific growth rates. Growth rates of pico-phytoplankton in lakes along a trophic gradient ranged from 0.10 to 2.14 day−1 (Weisse 1993). In the oceans the in situ growth rate of Synechococcus was likely 0.7 day−1 (1 doublings/day) (Furnas and Crosbie 1999). Estimates of Pcy growth rates from Lakes Biwa and Baikal were 0.65 and 0.4 day−1, respectively (Nagata et al. 1994, 1996) and from Lake Kinneret ranged from 0.29 to 0.60 day−1 (Malinsky-Rushansky et al. 1995) all fall within published ranges. The maximum net growth rate of unicellular cyanobacteria in oligotrophic Lake Stechlin was 0.23 day−1 (Padisák et al. 1997) while in Lake Balaton it was 2.27 day−1 (Mastala et al. 1996). Based on studies of 48 lakes in Quebec, Ontario and New York State, Lavallée and Pick (2002) obtained a maximum growth rate of 1.93 day−1. Pcy growth in Lake Maggiore lies between 0.28 and 1.14 day−1 as net growth rate and 0.91–2.36 day−1 as potential growth rate measured using the frequency of dividing cells (FDC) method (Callieri et al. 1996 b).

One of the selective advantages of small cell size in low nutrient environments is that cells are less limited by molecular diffusion of nutrients because of their increase in surface area-to-volume ratio (Raven 1986; Chisholm 1992). The prokaryotic structure of the Pcy cell also gives them the lowest costs for maintenance metabolism, and this has been cited as the primary reason for their success in oligotrophic conditions (Weisse 1993).

The model outlined by Stockner (1991b) of an increase of picophytoplankton abundance and biomass and decrease of its relative importance with the increase of phosphorus concentration in lakes has been widely accepted and confirmed in marine and freshwater systems (Bell and Kalff 2001). Using the extensive freshwater database of Vörös et al. (1998), Callieri and Stockner (2002), and successively Callieri et al. (2007) enriched the dataset at the ultra-oligotrophic extreme, and confirmed a positive correlation between the numbers of Pcy and extant trophic conditions in a wide range of waterbodies. Moreover, the percent contribution of Pcy to the total phytoplankton biomass and production decreased with increasing lake trophic state.

Figure 8.16 provides a comparison of the results of Callieri et al. (2007) with those of Bell and Kalff (2001). The data for Pcy from ultra-oligotrophic pristine lakes in northern Patagonia (Argentina) cluster in the same position as those from marine systems, suggesting a common ecological response in the various environments, despite the phylogenetic differences of the organisms.

4 Factors Affecting Community Dynamics and Composition

4.1 Biotic Versus Abiotic Regulation

Debates about the relative importance of biotic regulation versus abiotic forcing in driving population fluctuations have been recurring over decades in all fields of ecology, and microbial ecology is no exception. In a study on different terrestrial and aquatic communities Houlahan et al. (2007) found that abiotic factors provide the primary forcing that drives temporal variability in species abundance. We know that the complex changeability of community structure is related to a spectrum of environmental variability through the interplay of intrinsic (basin morphometry, thermal stratification, wind mixing) and external factors (e.g. supply of nutrients) (Harris 1980). The exploitation of environmental variability by the Pcy community is the result of evolutionary mechanistic adaptation and the interrelation with other primary producers of larger size and with predators. Adaptation to a changing environment, with phasing of fluctuating events, can subject the community to dominance by the fittest and most adaptive available species. These concepts should be evaluated on the light of the new conceptual framework of community ecology, the meta-community, which considers the communities as shaped at different spatial scales (local and regional) (Wilson 1992; Leibold et al. 2004). Therefore in the debate on biotic versus abiotic regulation of community structure and dynamics we need to consider that local communities are not isolated but are linked by dispersal of multiple, potentially interactive, species (Logue and Lindström 2008).

4.2 Lake Morphometry and Thermal Regime

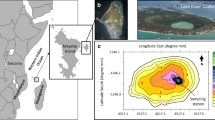

In order to interpret Pcy dynamics in freshwaters it is imperative to take into consideration the morphometric characteristics and thermal regime of a lake. The community composition of the Pcy can strongly depend on lake typology and morphogenesis. In a survey covering 45 lakes and ponds, Camacho et al. (2003) found that picocyanobacterial development was favoured by the stability of the vertical structure of the lake; that is by the inertial resistance to complete mixing owing to vertical density differences and to a long hydrological retention time. In lakes with relatively high water inflow and short retention time, Pcy are scarce. Far from this situation are deep lakes with a complex basin morphometry such as large sub-alpine lakes. In one of these lakes (Lake Maggiore) the Pcy population densities during summer stratification are high but with a pronounced North–south gradient due to a high retention time and peculiar characteristics along the lake axis (Fig. 8.17) (Bertoni et al. 2004). Lake Constance, with a different basin morphometry, has a less pronounced Pcy gradient (Weisse and Kenter 1991).

Map of the spatial heterogeneity of picocyanobacteria (Pcy) abundance in Lake Maggiore during spring. The northern basin of the lake contributes less total nitrogen and total phosphorus than the basin for the rest of the lake (Bertoni et al. 2004, modified)

Pcy composition and abundance vary conspicuously among shallow lakes, with a strong dependence on trophic condition (Stockner 1991a; Søndergaard 1991), altitude (Straškrabová et al. 1999b and cited references), oxidization-reduction conditions (Camacho et al. 2003) and the presence of dissolved humics (Drakare et al. 2003). It is therefore difficult to predict Pcy abundance in shallow lakes without considering the physical and chemical characteristics of the water. In a study of shallow humic lakes of the Boreal Forest Zone, Jasser and Arvola (2003) found Pcy to be light and temperature limited, whereas in humic Swedish lakes dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentration was the factor most influencing Pcy composition (Drakare et al. 2003).

Lake thermal structure influences Pcy abundance and dynamics of Pcy due to both the effect of temperature per se and mass movements of the water in response to density gradients. In general a temperature increase enhances the potential growth rate of phytoplankton, increasing the reaction rate of RUBISCO (Beardall and Raven 2004). Marine Synechococcus reacts promptly to the temperature increase in laboratory experiments (Fu et al. 2007), and in a 5-year study on Lake Balaton Pcy abundance was positively correlated to water temperature (Vörös et al. 2009). Nevertheless the influence of temperature on the abundance of Pcy in lakes is difficult to separate from the influence of seasonal and geographical location. The widespread assumption that temperature is the driving force for growth and development of microorganisms does not apply so clearly for Pcy in nature. Among diverse marine habitats Li (1998) found a direct relationship between Pcy mean annual abundance and temperatures below 14°C; above 14°C nitrate concentrations were very low and may therefore replace temperature as the most significant. At higher temperatures other factors can also become dominant and control Pcy growth. Weisse (1993) suggested the importance of temperature as triggering the onset of Pcy growth in marine and freshwaters, but not for regulating their population dynamics. In Lake Maggiore the maximum Pcy concentration occurs near the thermocline and at temperatures between 18°C and 20°C (Callieri and Piscia 2002) (Fig. 8.18). This provides an example of where temperature not only has a direct effect on the cell, but also helps to maintain a density gradient which hinders sedimentation (Callieri 2008). Vertical gradients of water density have a profound effect on the distribution and diversity of Pcy in the metalimnion, upper hypolimnion and mixolimnion.

Isotherm map of Lake Maggiore (Northern Italy), 0–50 m layer during 1998. The crosses indicate the highest values of picocyanobacteria abundance. Depths with 10 % of surface solar radiation are also given (thick line). Vertical bars indicate thermocline extension (From Callieri 2008)

4.3 Nutrients, Light Limitation and pH

The main difference between marine and freshwater Pcy is in the differential regulation of primary production by nitrogen, iron and phosphorus. In lakes, primarily phosphorus has been regarded as the limiting nutrient (Schindler 1977, 2006), whereas in the oligotrophic oceans nitrogen and iron are considered the ultimate nutrients limiting primary production (Tyrrell 1999). Nevertheless, in the Mediterranean Sea and in the North Pacific subtropical gyre, a climate-related shift from an N- to P-limited ecosystem over the past several decades has been observed (Moore et al. 2005), due to increased nitrogen fixation (Karl et al. 1997). Conversely, in ultra-oligotrophic lakes nitrogen deficiency, even more than phosphorus, can be the cause of the low productivity (Stockner et al. 2005; Diaz et al. 2007). Furthermore nutrient co-limitation can occur in oligotrophic systems (Mills et al. 2004), where more than one nutrient may effectively co-limit biomass production (Mackey et al. 2009). Thus, past assumptions about whether the N or P is the proximate or ultimate nutrient limiting the productivity of phytoplankton populations in marine and freshwater systems are re-opened to debate.

As regard Pcy we may infer from the Stockner model that as lakes or oceans become more nutrient depleted, i.e. oligotrophic, then the greater the importance and relative contribution of Pcy to total autotrophic biomass (Bell and Kalff 2001). The success of Synechococcus spp. in oligotrophic systems can also be explained by their high affinity for orthophosphate (Moutin et al. 2002) and their maximum cell specific P-uptake rates that are competitively superior to algae and other bacteria under a pulsed supply (Vadstein 2000). Actually it has been demonstrated that growth rates of marine Pcy, under limitation by NH +4 , PO 3−4 , Fe or light, are seldom completely stopped; moreover, cell quotas are low as can be expected for such small cells (Timmermans et al. 2005). Iron’s limited bioavailability makes it limiting despite its abundance. The siderophores are iron-chelating compounds produced by cyanobacteria (Murphy et al. 1976; Hopkinson and Morel 2009). Siderophore production can provide a competitive advantage to cyanobacteria over other algae during iron stress, and can alter the bioavailabity of iron to the aquatic community (Wilhelm 1995). Nevertheless it has been found that in diluted aqueous environment endogenous siderophore uptake is inefficient. In this type of environment, reductive Fe uptake is an effective strategy in the acquisition of organically bound iron (Kranzler et al. 2011). In laboratory studies Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus marine strains, under P-limited conditions, showed high C:P and N:P ratios thus producing new biomass with a bioelemental stoichiometry well in excess of the canonical Redfield ratio (Bertilsson et al. 2003; Heldal et al. 2003). These results allow us to envisage the potentially great importance of Pcy for enhancing carbon sequestration with the ensuing potential to change the structure and complexity of pelagic food webs (Bertilsson et al. 2003).

An alternative explanation for the relative success of Pcy to grow at low inorganic P concentrations is given by the ability of their cells to utilise, in addition to PO 3−4 , organic sources of phosphate. Under orthophosphate limitation, algae hydrolyse ambient organic phosphates using extracellular phosphatases and transport the orthophosphate into their cells (Jansson et al. 1988). Whitton et al. (1991) compared the growth of cyanobacterial strains in the presence of organic or inorganic phosphate, finding a similar growth rate. The extracellular phosphatase activity (APA) in several phytoplankton species has been demonstrated by the enzyme-labelled fluorescence (ELF) technique (Nedoma et al. 2003; Štrojsová et al. 2003). This technique permits both the quantification of the enzyme produced and the microscopic localization of the enzyme. Pcy can produce alkaline phosphatases under conditions of phosphate starvation (Simon 1987) but, up to now, none has been observed to show APA-activity using the ELF technique (A. Štrojsová, 2002 personal communication). The method detects only phosphomonoesterase, not phosphodiesterase, activity; therefore caution is needed in interpreting the significance of surface phosphatase activity (Whitton et al. 2005). A genetic study on marine strains has revealed inter-strain variability in the presence and/or absence of genes governing P-acquisition, scavenging and regulation (Moore et al. 2005). Such genetic variability will clearly influence the different physiological responses to low P concentrations of individual strains, e.g. the production of APA.

There are other alternative ways for Pcy to overcome P limitation. Two pathways are of interest: one has been discovered from the presence of genes necessary for phosphonate utilization in the genome of Pcy (Palenik et al. 2003; Ilikchyan et al. 2009). Phosphonates are refractory high-molecular-weight components of the dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP) pool. Marine and freshwater Pcy have the phnD gene, which is thought to encode a phosphonate-binding protein, and in a study induction of phnD expression in P-deficient media was demonstrated (Ilikchyan et al. 2009). This suggests that in P-limiting conditions Synechococcus is able to survive utilizing this refractory form of DOP, derived also from a common herbicide. The other alternative derives from the ability of marine cyanobacteria, and particularly Prochlorococcus, to substitute sulphate (SO 2−4 ) for PO 3−4 in lipids, thus minimising their phosphorus requirement by using a ‘sulphur-for-phosphorus’ strategy. The strategy of synthesizing a lipid that contains sulphur and sugar instead of phosphate could represent a fundamental biochemical adaptation of Pcy to dominate severely phosphorus-deficient environments (Van Mooy et al. 2006, 2009).

There is evidence that ammonium is the preferred form of nitrogen for Synechococcus in culture (Glibert and Ray 1990), but when ammonium is exhausted Synechococcus can take up nitrate, thanks to a regulatory mechanism that can induce expression of nitrate reductases (Bird and Wyman 2003). Also, under severe N-limitation Pcy can alternatively use the nitrogen reserve that exists in phycobiliproteins as amino acids storage molecules (Grossman et al. 1993). The success of Pcy under low light conditions is tightly coupled with competition for limiting nutrients. In this way, low-light adaptation in Synechococcus is probably of greatest ecological advantage when low-P conditions constrain the growth of all autotrophs (Wehr 1993). Thus the pulsed addition of P can have an interactive effect, because it increases the prevalence of larger algae that can alter the light climate, thereby increasing light limitation which will enhance the growth of Pcy.

Good evidence on the interplay between P, irradiance and primary production of Pcy and how it is mediated in the field is difficult to envisage, but some clues come from the comparison of six ultra-oligotrophic North Patagonian lakes and from the subalpine Lake Maggiore (Fig. 8.19) (Callieri et al. 2007). In the ultra-oligotrophic lakes Pcy production was inversely significantly correlated to PAR but not to P, indicating that in such extremely nutrient deplete ecosystems, low P concentrations were not the limiting resource driving Pcy production. One interpretation of these results is that high irradiance is photo-inhibiting Pcy production and hence is the key driving variable and not phosphorus concentration. Conversely, in the oligo-mesotrophic Lake Maggiore neither P nor light were not correlated to Pcy production. Similar finding are reported by Lavallée and Pick (2002) who found a lack of correlation between pico-phytoplankton growth rates and any form of dissolved phosphorus.

Multiple linear regression analysis of the Pcy primary production (PP) versus irradiance (PAR) and P (total dissolved PO4-P) in: (a) Lake Maggiore; (b) six north Patagonian lakes (Partly from Callieri et al. 2007, modified)

Light is an important factor in niche differentiation for Pcy. The response of Pcy to different light intensity has been studied both in laboratory experiments and in situ, and it has been shown that the optimum growth rate of Synechococcus occurs at low light intensities (Waterbury et al. 1986), notably at a quantum flux of 45 μmol photon m−2 s−1 where their highest growth has been observed (Morris and Glover 1981). These findings agree with field observations where the maximum peak abundance has been found deep in the Atlantic mixed layer (Glover et al. 1985), and in the DCM (deep chlorophyll maximum) of Lake Stechlin (Gervais et al. 1997) and of North Patagonian ultra-oligotrophic Andean lakes (Callieri et al. 2007). In lakes worldwide Pcy have been found at a variety of depths and light irradiance (Fahnenstiel and Carrick 1992; Nagata et al. 1994; Callieri and Pinolini 1995; Callieri and Piscia 2002), confirming the classification of Synechococcus as a euryphotic organism (Kana and Glibert 1987b). One explanation of Pcy tolerance and adaptation to high irradiance is the identification of a process that prevents photo-damage in open ocean Pcy by maintaining oxidized PSII reaction centres, channeling the electrons from PSI to oxygen through a specific oxidase (Mackey et al. 2008). Because of this process Pcy possess an efficient mechanism for dissipating PSII excitation energy, decreasing any potential photo-damage. Nevertheless the relative phylogenetic complexity of the Synechococcus and Cyanobium genera does not presently permit the simple discrimination of high light- and low light-adapted ecotypes, as has been attained for Prochlorococcus (Scanlan and West 2002; Ahlgren and Rocap 2006).

Synechococcus ecotypes exhibit differences in their accessory pigments that affect their adaptation to spectral light quality. It was found that in highly coloured (humic) lakes, non-phycoerythrin cells dominated numerically, while in clearer, oligotrophic hard-water lakes, phycoerythrin-rich cells were the most abundant (Pick 1991). The influence of underwater light quality on the selection of Pcy types having different pigment content has been studied in many aquatic systems, covering a wide spectrum of trophic states and underwater light quality (Vörös et al. 1998; Stomp et al. 2007). Vörös et al. (1998) found that the percentage of PE-rich cells in the total Pcy community increased with increasing values of the KRED/KGREEN ratio, while concurrently the total chlorophyll a concentration decreased and the waters became more transparent and less productive (Fig. 8.20). In laboratory experiments, it has been shown that Pcy grow better when they have a phycobiliprotein whose absorption spectrum is complementary to that of the available light (Callieri 1996) and subsequent experiments showed that PE-rich cells prevail in green light and PC-rich cells in red light but when grown together in white light, can co-exist, absorbing different parts of the light spectrum (Stomp et al. 2004). The importance of red light for phycocyanin and biomass production has been shown in laboratory experiments with a PC-rich Synechococcus strain (Takano et al. 1995), while blue and green wavelengths of light are used more efficiently than red of similar intensity by PE-rich Synechococcus (Glover et al. 1985).

Relative abundance of phycocyanin-rich cells (PC) and phycoerythrin-rich cells (PE) in different aquatic systems in relation to the underwater light climate expressed as the ratio between the extinction coefficient of red and green wavelengths (KRED/KGREEN). When the KRED/KGREEN ratio is >1 the extinction of red light is high and the dominant underwater light is green. Very low values of KRED/KGREEN ratio indicate a red dominant underwater radiation (Modified from Vörös et al. 1998)

The pigment composition of Pcy represents a characteristic spectral signature that can define individual strains, but closely related strains can have different pigment composition (Everroad and Wood 2006). In particular both pigment types have been found in several non-marine Pcy clusters (Crosbie et al. 2003b). A new clade, sister to Cyanobium, was reported from oceanic waters, based upon phylogenetic analysis of concatenated 16S rDNA and rpoC1 data sets (Everroad and Wood 2006). This large clade includes both PE-rich and PC-rich strains. Similarly, marine cluster B (MC-B) also contains PE-rich and PC-rich strains, and this cluster is polyphyletic, consisting of at least two different sub-clusters (Chen et al. 2006). The phylogeny derived from the cpcBA operon of the green PC pigment was better able to separate differently pigmented Pcy than 16S rRNA-ITS phylogeny (Haverkamp et al. 2008). The ecological implication of these findings is that Synechococcus from different lineages can occupy different niches; or alternatively, if the environment offers greater variability and more suitable niches, like in the Baltic Sea (Haverkamp et al. 2009) or in Lake Balaton (Mózes et al. 2006), they can coexist.

Laboratory experiments with freshwater strains from different phylogenetic groups acclimated at low and medium irradiance show that photosynthetic responses are strain-specific and sensitive to photo-acclimation (Callieri et al. 2005; Moser et al. 2009) (Fig. 8.21). PE-rich Pcy from Group B, subalpine cluster I (sensu Crosbie et al. 2003a, b), are more sensitive to photo-acclimation than PC-rich cells from Group I and from Group A, Cyanobium gracile cluster. Therefore ecophysiological differences seem to be more related to the pigment type. Nevertheless the extent of photo-adaptation is strain-specific and depends on the duration of the photo-acclimation (Moser et al. 2009).

Photosynthesis/Irradiance (P/E) curves of three Pcy strains: (a) PE-cells MW4C3 from the Group B, Subalpine cluster; (b) PC-cells MW100C3 from Group I; (c) PC-cells BO8801 from Group A, Cyanobium cluster. Dark symbols = medium light acclimation (100 μmol photon m−2 s−1); light symbols = low light acclimation (10 μmol photon m−2 s−1) (From Moser et al. 2009, modified)

Synechococcus strains are most often grown in a medium at a neutral pH (Stanier et al. 1971). Their preference for neutral or slightly alkaline conditions is also evident in their abundance and distribution patterns in freshwater ecosystems (Stockner 1991b). The trend towards Pcy disappearance with decreasing pH and their replacement by picoeukaryotes has been noted in three dystrophic Canadian lakes (Stockner and Shortreed 1991) and in several low pH, humic Danish lakes (Søndergaard 1991). Also in seven humic lakes situated in Lappland (Sweden) pH was among the abiotic variables most affecting pico-phytoplankton distribution and abundance (Drakare et al. 2003). The effect of lake acidification on the microbial community can be indirect by altering community structure and hence carbon flow to higher trophic levels, or direct by inducing physiological stress. In a study on a Swedish acidified lake before and after liming a non-edible CPcy, Merismopedia tenuissima, was the dominant in the late summer phytoplankton community in the naturally acidic lake, but the population was removed by liming (Bell and Tranvik 1993; Blomqvist 1996). Unfortunately the authors present no data on Pcy abundance in this lake. However, they suggest a likely allelopathic mechanism to explain the population dynamics of Merismopedia tenuissima (Blomqvist 1996; Vrede 1996). In Lake Paione Superiore, an acid sensitive lake above the tree line in the Italian Alps, Pcy populations are very low, and their contribution to microbial food webs appears to be negligible (Callieri and Bertoni 1999). In alpine lakes the effect of low pH and of photo-inhibition has been indicated as the major cause of low Pcy numbers found in those lakes (Straškrabová et al. 1999a). The presence of a shift from Pcy to net plankton has been described in mesocosm experiments (Havens and Heath 1991), and it has been noted that as pH declines the proportion of larger species tends to increase and become dominant (Schindler 1990). Nevertheless, to our knowledge no experimental studies of the influence of pH on Pcy strains have been done, so at this stage it is difficult to discuss ranges of pH tolerance by Pcy or physiological mechanisms of adaptation to low pH in lakes. The only possible generalisation at this stage is that Pcy and many CPcy are not common in lakes with a pH <6.0, and are seldom mentioned or included in studies on acidic lakes because they are probably in low abundance or absent.

4.4 Ultraviolet Radiation

There is considerable evidence that ultraviolet radiation (UVR) has a pronounced influence on aquatic organisms and on their community structure in both marine and freshwaters (Häder et al. 2007). Picoplankton are thought to be particularly vulnerable to UVR because: (1) their small size does not permit the intracellular production of sunscreen compounds (Garcia-Pichel 1994); (2) the small ‘package’ effect leads to higher pigment-specific absorption (Morel and Bricaud 1981) and (3) the distance between the cell surface and the nucleus (DNA) is shortened and the DNA damage induced by UV-B is increased. Thymine dimers like cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) are frequently built upon DNA lesions under UV-B radiation and have been recovered in marine phytoplankton (Buma et al. 1995) and Argentinean lakes (Helbling et al. 2006).

Although the higher vulnerability of picoplankton is predictable in theory, contrasting results have been obtained in field studies. Laurion and Vincent (1998) studying size-dependent photosynthesis in a sub-arctic lake have shown that cell size is not a good index of UVR sensitivity. Further, they indicated that Pcy are less sensitive to UVR fluxes and that genetic difference between taxa, more than size, are important in determining the tolerance to UVR; while other authors obtained evidence of an higher vulnerability of smaller algae to UVR (Kasai et al. 2001; Van Donk et al. 2001). A high Pcy sensitivity to UVR radiation in comparison to nano-phytoplankton was observed in the biological weighting functions (BWF) in a high altitude alpine lake by Callieri et al. (2001) (Fig. 8.22). A possible interpretation of these contrasting results is that small cells are likely more susceptible to DNA damage than large cells but they are able to acclimate faster, within hours (Helbling et al. 2001), and are more resistant to photosystem damage (Villafañe et al. 2003).

Biological weighting functions (mW m−2 nm−1)−1 for inhibition of photosynthesis for L. Cadagno picophytoplankton (blue line) and whole assemblage (red line) on 13 September 1999. Broken lines show estimated 95% confidence interval for individual coefficient estimates (From Callieri et al. 2001)

The spectral quality of the UVR exposure, its duration and photon flux density, strongly influences the effect on phytoplankton communities (Harrison and Smith 2009). The damaging power of radiation generally increases from PAR through UV-A into the UV-B wavebands, but this general pattern may still be questioned (Harrison and Smith 2009). There is evidence that many aquatic organisms react promptly to UV-B stress by producing protective substances such as mycosporine-like amino acid compounds (MAAs) (Sinha and Häder 2008), which have absorption maxima ranging from 310 to 359 nm (Carreto et al. 1990; Karentz et al. 1991). In particular cyanobacteria react in response to UV-A radiation by producing an extracellular yellow-brown pigment – scytonemin, that absorbs most strongly in the UV-A spectral region (315–400 nm) (Garcia-Pichel and Castenholz 1991; Dillon et al. 2002). The sunscreen capacities of MAAs and scytonemin are higher if they are present concurrently, and their production is considered an adaptive strategy of photo-protection against UVR irradiance (Garcia-Pichel and Castenholz 1993). Also it is recognized that the UV-B induced production of CPD is counterbalanced by repair mechanisms based on the production of enzymes known as photolyases (Jochem 2000).

Therefore aquatic microorganisms have numerous mechanisms of protection against UVR which influence their global community responses in nature. It has been recognized that many of the effects of solar UVR are caused by wavelengths in the UV-A range, which are not affected by changes in stratospheric ozone (Sommaruga 2009). The higher photo-inhibiting effect of UV-A than UV-B on different size fractions of phytoplankton has been described in several different lakes (Callieri et al. 2001, 2007; Villafañe et al. 1999) and in marine habitat as well (Villafañe et al. 2004; Sommaruga et al. 2005). Callieri et al. (2001) explain the negligible impact of UV-B on in situ phytoplankton production with the lower weighted irradiance brought about by the high Kd at short wavelengths and low incident flux, whereas with UV-A the weighted irradiance is higher due to a greater incident flux and lower Kd.

Mixing is an important factor affecting the degree of exposure to UVR. Vertical mixing transports the cells to depth where active repair takes place and subsequently re-exposes them to higher UVR, upon transport again to near surface depths. Species which form surface blooms, like colonial Microcystis aeruginosa, can also withstand high UVR, synthesizing carotenoids and MAAs (Liu et al. 2004). Toxin biosynthesis by M. aeruginosa may also be influenced by UVR, with the idea that microcystins present inside or outside the cell function as a metal ligands to reduce metal toxicity (Gouvea et al. 2008). The hypothesis that UVR and the bioavailability of trace metals can act as a trigger for microcystin production is fascinating, and would help to explain the selective advantage of cystin production by M. aeruginosa, but it is not yet proven. To explain the resistance of CPcy to UVR it is interesting to note that the colonial morphotype of Microcystis can synthesise substances such as D-galacturonic acid, which is the main component of the slime layer of Microcystis (Sommaruga et al. 2009), and which may hence provide a protective function. To better understand the formation of microcolonies (Callieri et al. 2011) used PE-rich and PC-rich Synechococcus strains of different ribotypes acclimated at moderate (ML) and low (LL) light, and exposed the strains to different levels of UVR under controlled conditions. PE-rich Synechococcus acclimated to LL had a low carotenoid/chlorophyll a (car/chl) ratio but responded faster to UVR treatment, producing the highest percentages of microcolonies (Fig. 8.23) and of cells in microcolonies. Conversely, the same strain acclimated to ML, with a higher car/chl ratio, did not aggregate significantly. These results suggest that microcolony formation by PE-rich Synechococcus is induced by UVR if carotenoid levels are low. PC-rich Synechococcus formed a very low percentage of microcolonies in both acclimations even with low car/chl ratio. It is likely that some Synechococcus strains react to UVR finding a refuge through a morphological adaptation, inclusive of slime layer protection, similar to that noted in Microcystis (Sommaruga et al. 2009). Therefore, in the equilibrium between single cells versus microcolonies or even larger colonial morphologies, the importance of solar radiation (UVR and PAR) should not be underestimated but considered together with other important factors like the nutrient status of the ecosystem and grazing.

Percentage of microcolony number on the sum of single-cell plus microcolony number. PE and PC-rich Synechococcus strains in the treatments (+UVR, +UVR50, -UVR, and control) at two acclimations (LL: 10 μmol m-2 s-1 and ML: 100 μmol m-2 s-1), during experiment times (6 days) (from Callieri et al. 2011, AEM)

4.5 Biotic Interactions

Grazing studies have been stimulated by several new methodologies. Rates of Pcy removal by grazers have been measured using five basic techniques: (1) metabolic inhibitors (Campbell and Carpenter 1986b); (2) diffusion chambers and the dilution technique (Landry and Hassett 1982); (3) fluorescent labelled particles (FLP) (Sherr et al. 1987); (4) direct cell counts (Waterbury et al. 1986) and (5) radioisotope-labelled prey (Iturriaga and Mitchell 1986). Some of these methods have been improved (Landry et al. 1995; Sherr and Sherr 1993) and others developed with the use of modern techniques, e.g. by combining FLP and flow cytometry for cell counting (Vázquez-Domínguez et al. 1999) or using a RNA stable isotope probing technique (Frias-Lopez et al. 2009). In the past various growth inhibitors were tested, including the eukaryote inhibitors colchicine and cycloheximide, which have been used to stop protozoan Pcy grazing activity (Campbell and Carpenter 1986b; Caron et al. 1991). Liu et al. (1995) used kanamycin as an effective growth inhibitor of Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus to estimate growth and grazing rates. Using this approach the mortality of Pcy in marine systems due to grazing has been estimated to range from 43% to 87% of growth rate in marine systems (Liu et al. 1995).

It is not surprising that the existence and continuing development of so many methodologies to measure grazing has produced such diverse and often contradictory results in the literature. For example Sherr et al. (1991) estimated that in Lake Kinneret ciliate carbon requirement could not be obtained only from a Pcy energy source, and they suggest that picoeukaryotic cells must be grazed as well to fulfil growth requirements. However, Šimek et al. (1996) show that some of the most common freshwater ciliate species can survive solely on a diet of Pcy. A tentative annual balance of energy flow in a deep oligotrophic lake estimated that between 83% and 97% of the carbon produced by Pcy is taken up by protozoa and channelled to metazooplankton (Callieri et al. 2002). Nevertheless, there are large losses of organic carbon through respiration during this transfer, along the trophic chain (Sherr et al. 1987). These discrepancies and contrasting results have enhanced the discussion to improve our understanding of the impact of different grazers (protozoans and metazooplankon) on Pcy and on energy transfer, along with this “trophic repackaging”.

Heterotrophic and mixotrophic nanoflagellates and small ciliates have been recognised as the most important grazers of Pcy (Stockner and Antia 1986; Bird and Kalff 1987; Weisse 1990; Christoffersen 1994; Šimek et al. 1995; Sanders et al. 2000). Among the ciliates (Fig. 8.24), oligotrich species and some scuticociliates, which are sometimes at the borderline between nano- and microplankton (<30 μm), can be important picoplanktivores in lakes (Šimek et al. 1995; Callieri et al. 2002). Šimek et al. (1996) have summarised three ecological categories of freshwater ciliates with different feeding strategies and a decreasing importance of pico-size prey in their diet. Among the most efficient suspension feeders there are some very active Pcy grazers, e.g. Vorticella aquadulcis (Fig. 8.25), Halteria grandinella, Cyclidium and Strobilidium hexachinetum. These protozoa are able to graze 560, 210, 80, 76 Pcy ciliate−1 h−1, respectively, with clearance rates highly variable among taxa, 11–3150 nL × cells × h−1 (Šimek et al. 1996). In a warm-monomictic saline lake in Mexico lower uptake rates by vorticellids and mixotrophic Euplotes have been measured, ranging from 16 to 227 Pcy ciliate−1 h−1 (Peštová et al. 2008), but the authors noted the importance of both groups as selective Pcy grazers. Large mixotrophic ciliates, common in ultra-oligotrophic south Andean lakes, are also recognised as preying upon Pcy (Modenutti et al. 2003; Balseiro et al. 2004).

Despite the importance of ciliate grazing on Pcy in some systems, it is generally recognized that among protozoa, both heterotrophic and mixotrophic nanoflagellates are responsible for 90% of the grazing of Pcy and bacteria; whereas ciliates accounted for only 10% (Pernthaler et al. 1996). A study on Lake Maggiore showed that heterotrophic nanoflagellates (HNF) ingested from 0.5 to 3 Pcy h−1, while ciliates ingested from 18 to 80 Pcy h−1 (Callieri et al. 2002). Nevertheless, at the community level, the grazing impact of HNF was one order of magnitude higher than that of ciliates (maxima: 8,000 Pcy mL−1 h−1 and 400 Pcy mL−1 h−1, respectively) (Callieri et al. 2002). In Lake Tanganika similar results were obtained with the higher impact of HNF (av: 8027 Pcy mL-1 h-1) than of ciliates (maxima: 1355 Pcy mL-1 h-1) on Pcy grazing in the dry season (Tarbe et al. 2011). Pernthaler et al. (1996) have emphasised the influence of community composition and taxa-specific clearance rates on the grazing impact on bacteria and Pcy. The size of the prey, its morphological characteristics and nutritional value have been indicated as important factors in the selection carried out by the predators (Šimek and Chrzanowski 1992; Jezberová and Komárková 2007; Shannon et al. 2007). In particular the involvement of the proteinaceous cell surface (S-layer) as grazing protection has also been suggested for freshwater Actinobacteria (Tarao et al. 2009). Morphological characteristics can therefore be considered as group-specific traits and can greatly influence the success of the group in an ecosystem (Tarao et al. 2009). Protozoa grazing and in particular nanoflagellates can influence the characteristics of bacterial and Pcy communities and lead to changes in their structural and taxonomic composition. A laboratory study with 37 Synechococcus strains showed clearly that prey selection discriminates at the strain-specific level (Zwirglmaier et al. 2009).

The selection of food as described for metazooplankton generally takes place during food capture and processing (Porter 1973). According to the theory of “selective digestion” prey selection takes place inside the food vacuoles (Boenigk et al. 2001). The fate of the prey is decided at the moment of digestion, with the possibility of very fast prey-excretion after the uptake. Knowledge of the mechanism of Pcy consumption and excretion/digestion is species-specific both for prey and predator. Boenigk et al. (2001) demonstrated that prey characteristics and predator satiation strongly influence the ingestion and digestion process, e.g. the digestion strategies of Cafeteria, Spumella and Ochromonas are different; with Pcy rapidly excreted while bacteria were directly digested in the food vacuoles. Amoebae can perform food selection in the food vacuole and excrete the toxic or unpalatable prey items similarly to nanoflagellates (Liu et al. 2006; Dillon and Parry 2009).

Ciliates and nanoflagellates can also serve as a trophic link between Pcy production and Daphnia production, thereby upgrading the nutritional value of Pcy as a food source by producing essential lipids such as sterols (Martin-Creuzburg et al. 2005; Martin-Creuzburg and Von Elert 2006; Bec et al. 2006). Among mesozooplankton, Daphnia has the capacity of feeding on a wide particle size range (1–50 μm), filtering Pcy as well (Gophen and Geller 1984; Stockner and Porter 1988) (Fig. 8.26). Together with Daphnia, several cladoceran genera, including Bosmina, Eubosmina and Ceriodaphnia, are able to ingest Pcy (Weisse 1993). Suspension-feeding cladocerans may have a direct grazing effect on Pcy and an indirect effect by regenerating nutrients (Carrillo et al. 1996; Balseiro et al. 1997). The recycling of excreted nutrients moves the nature of algal-bacterial interactions from one of competition to commensalism (Reche et al. 1997).