Abstract

This chapter compares and contrasts factor investing and sector investing and then seeks a compromise by optimally exploiting the advantages of both styles. Our results show that sector investing is effective for reducing risk through diversification, while factor investing is better for capturing risk premia and so pushing up returns. This suggests that there is room for potentially fruitful combinations of the two styles. Presumably, by combining factors and sectors, investors would benefit both from the diversification potential of the former and the risk premia of the latter. The tests reveal that composite strategies are particularly attractive; they confirm that sector investing helps reduce risks during crisis periods, while factor investing can boost returns during quiet times.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Factor investing has recently become a huge success in asset allocation (Ang 2014). But its supposed superiority over other portfolio management techniques has yet to be proven. To fill that gap, we lay down a challenge to factor investing by organizing a contest pitting it against a well-established competitor, the classical industry-based approach to asset allocation (Sharpe 1992; Heston and Rouwenhorst 1994).Footnote 1 We compare the performance of factor-based and industry-based asset allocation strategies in the investment universe composed of US equities. We contrast the mean-variance performance of diversified portfolios made up of US industry sectors with diversified component portfolios of the five factors developed by Fama and French (2015). We duplicate all the trials for long-only portfolios (no short sales) and long-short ones (unlimited short sales accepted).Footnote 2 This duplication is a key aspect since factor-based asset management relies on short-selling and systematic portfolio rebalancing.

Our contest reveals no overall winner. In fact, we find superiority for each style depends on the specific time periods and investor restrictions. The alphas of factors with respect to the market inflate expected returns, while sectors reduce risks through high diversification potential. Factor investing tends to dominate when short sales are permitted. By contrast, when short-selling is excluded, industry-based allocation is preferable, especially for highly risk-averse investors. These results lead us to conjecture that factors and sectors could be complementary investing styles, and that combining them should help enhance financial performance, at least under some configurations of short-selling ability and/or risk preferences. Our empirical investigation suggests that composite portfolios made up of sectors and factors are particularly attractive under two types of circumstances. First, for long-only portfolios during non-crisis periods, a mixture of sectors and factors largely dominates both factor-only and industry-only investment styles. Second, unconstrained investors will find it best to combine sector and factor investments, especially during crisis periods. This chapter draws on the result that industry returns are difficult to explain using existing factors (Lewellen et al. 2010). It also confirms that industry portfolios can be used by investors facing portfolio restrictions (Bae et al. 2016). Further research is needed to investigate the optimal way to combine the different investing styles.

2 Data and Methods

Our investment universe is made up of US stocks listed on the NYSE, Amex, and Nasdaq, with a Centre for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) share code and positive book equity data over the period July 1963–December 2016. We use the risk factors proposed by Fama and French (1992, 2015) and Carhart (1997). All our data are retrieved from Kenneth French’s website.Footnote 3 They include (1) the size factor, Small Minus Big (SMB), which is the return on a portfolio of small stocks (bottom 30% in terms of market capitalization) minus that of a portfolio of big stocks (top 30% capitalization); (2) the value factor, High Minus Low (HML), equivalent to the return of a portfolio made of “value” stocks, that is, those with a high (top 30%) book-to-market ratio (book value of common equity divided by the market equity) minus that of a portfolio of “growth” stocks (bottom 30% book-to-market ratio); (3) the momentum factor, Winners Minus Losers (WML), which is the return of a portfolio of best-performing stocks (top 30%) minus that of a portfolio of worst-performing stocks (bottom 30%) over the previous year; (4) the profitability factor, Robust Minus Weak (RMW), the difference between the returns on diversified portfolios of stocks with robust and weak operating profitability (the ratio obtained from dividing annual revenues minus cost of goods sold and expenses by book equity); and (5) the investment factor, Conservative Minus Aggressive (CMA), the difference between the returns on diversified portfolios of low- and high-investment stocks. For each of these five long-short factors, we extract the long-leg and short-leg components. For example, from the SMB factor, we make two factor components: the first is made up of small stocks only, while the second is restricted to large stocks. Splitting similarly the five factors of Fama and French leaves us with ten factor components, which are (1) small, (2) big, (3) value, (4) growth, (5) robust profitability, (6) weak profitability, (7) conservative investment, (8) aggressive investment, (9) high momentum, and (10) low momentum. These components are considered as the elementary assets in optimal factor-based allocation.

As for sector investing, the dataset includes ten industry-based indices made up of U.S. stocks listed on the NYSE, Amex, and Nasdaq. Our sector-based portfolios are constructed from ten sectors: (1) non-durable consumer goods, (2) durable consumer goods, (3) manufacturing, (4) energy, (5) high tech, (6) telecom, (7) shops, (8) health, (9) utilities, and (10) others (mines, construction, building materials, transportation, hotels, entertainment, finance, etc.). Finally, we recorded the market index returns (value-weighted returns of all NYSE, Amex, or Nasdaq-listed US firms) and risk-free interest rates (one-month Treasury bill rate from Ibbotson Associates). To scrutinize the sensitivity of our results to market conditions, we used three different sample periods: (1) the full sample period; (2) the crisis period, which combines the recessions dated by the National Bureau of Economic Research with the bear-market periods identified by Forbes magazine; and (3) the non-crisis period.Footnote 4 They include the oil-shock-driven financial crises in the 1970s, the 1987 stock market crash, the 1998 Asian crisis, the 2000 e-crash, and the recent subprime crisis (see Table 11.1). We are dealing with discontinuous crisis and non-crisis sample periods, this has become standard practice in the empirical literature on financial crises (Goetzman et al. 2005).

The purpose of the contest is to examine the financial performance of factor and sector investing. In line with Ehling and Ramos (2006), we run tests on the mean-variance efficiency of the market portfolio in order to investigate the ability of factor-based and sector-based efficient frontiers to beat the market. The two tests we use for this are based on distances in the mean-variance plane. First, the test proposed by Basak et al. (2002) checks whether the horizontal distance between a portfolio and its same-return counterpart efficient portfolio is significantly positive. Second, the Brière et al. (2013) test is based on the vertical distance between a given portfolio and its same-return counterpart on the efficient frontier. The two tests offer complementary views on the mean-variance attractiveness of efficient portfolios.

3 Descriptive Statistics

Panel A in Table 11.2 provides the figures for all ten sectors and the market. The average annualized returns reveal that two sectors outperform all the others: non-durables (12.93%) and health (12.79%). The utilities, durables, and telecom sectors are the worst performers (10.01%, 10.23%, and 10.53%, respectively). The risk levels differ substantially across sectors. Volatilities range from 13.90% (utilities) to 22.26% (tech).Footnote 5 Skewness is negative for all but three sectors (durables, energy, health). Kurtosis is higher than 3.0 (between 4.10 and 7.80). The Sharpe ratios range from 0.45 (durables) to 0.85 (non-durables).

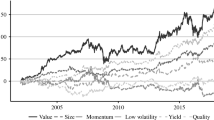

Panel B in Table 11.2 gives the corresponding information for our ten factor components. The annualized returns range from 8.32% (low momentum) to 15.23% (value). Volatilities lie between 15.02% (big) and 21.61% (low momentum). Skewness is negative for all factor components, except low momentum. The highest absolute value of skewness (0.62) corresponds to high momentum. This is consistent with the evidence reported by Daniel and Moskowitz (2016) and Barroso and Santa-Clara (2015) to the effect that, despite attractive Sharpe ratios, momentum strategies can lead to severe losses, making them unappealing for investors sensitive to extreme risks. Kurtosis ranges between 4.72 and 7.00. The Sharpe ratios range from 0.37 (low momentum) to 0.87 (high momentum), showing a slightly higher performance dispersion than for sectors. Six of the ten factor components generate significantly positive alphas. The five long legs of the Fama and French factors (small, value, robust profit, conservative investment, and high momentum) have positive alphas since they were built for that specific purpose. More surprisingly, the “big” factor also exhibits a significantly positive alpha.

Table 11.3 reports intra-group pairwise correlations, as well as correlations with the market, for sectors (Panel A) and factor components (Panel B), respectively. The average correlation computed for factor components (0.92) is much higher than for sectors (0.65). The high average correlation tends to indicate that diversification benefits will be harder to capture with factors than with sectors. However, correlations among sectors exhibit substantial heterogeneity. High correlations (above 0.80) are found for manufacturing, shops, and the last sector (“others”), which includes finance. In contrast, the correlations between the returns of utilities and durables, and between the returns of energy and tech are particularly low (0.42 and 0.45, respectively). The manufacturing sector is highly correlated with the market (0.94). Correlations between factor components are far more homogeneous, ranging from 0.74 (between low and high momentum) to 0.99 (between growth and aggressive investment). As expected, the highest correlation with the market is found for big stocks, which have the highest capitalization, and thus the largest share of the investment universe.

4 Contest

We consider six scenarios, which combine three sample periods (full sample period, crisis, non-crisis) with long-only and long-short portfolios. In each case, we determine two efficient frontiers, the first built from the ten sectors, the second from the ten factor components. Figure 11.1 shows the efficient frontiers and the market portfolio. For long-only investments, no frontier dominates any other. Figure 11.1a illustrates that the risk levels reached by sector-based portfolios are disconnected from those accessible with portfolios composed of factor components. This is because investors with high risk aversion will prefer diversified industry-based portfolios, whereas less risk-averse investors will prefer the opportunities based on factor components, which capture higher risk premia at the cost of higher levels of risk. Yet, a small portion of the factor-based frontier (expected return below 13%) is dominated by sector-based portfolios, meaning that investors holding these low-return portfolios made up of factor components are worse off than those holding sector-based portfolios. This dominance effect is stronger during crises (Fig. 11.1c), but it disappears during the non-crisis periods (Fig. 11.1e). For long-only portfolios, sector investing is a better strategy in troubled times, regardless of the investor’s level of risk aversion.

The picture is different for long-short portfolios, where factor components perform much better than their sector-based competitors. For the full sample (Fig. 11.1b), factor investing beats sector investing in every respect, since its efficient frontier sits uniformly above the other one. The same evidence applies to non-crisis periods (Fig. 11.1f) except for the far-left tail of the frontiers. The situation is more balanced for the crises (Fig. 11.1d), where the two frontiers intersect, so that sector investing looks particularly attractive to investors with high risk aversion, and portfolios composed of factor components are more suitable for their more risk-tolerant counterparts. The possibility of shorting allows investors to keep positive expected returns, which contrast with both the long-only frontiers and the market index during crises.

To test whether our style-based portfolios outperform the market, we use both the Basak et al. (2002) test, which computes the horizontal distance between the market portfolio and its same-return counterpart efficient portfolio, and the Brière et al. (2013) test, which exploits the vertical distance between the market portfolio and its same-variance counterpart efficient portfolio. In the few cases where the counterpart is inexistent (see Fig. 11.1), we use its closest proxy, located on the efficient frontier either on the left for the vertical test or upwards for the horizontal test. Table 11.4 reports the results. The winning style is such that it beats the market with the greatest distance, provided that this distance is significant at the 5% level. Table 11.4 presents the test results corresponding to the graphs in Fig. 11.1. They use geometric distances between the market portfolio and the efficient frontiers.

The results in Panel A (long-only portfolios) show that sector investing is the winner for all trials that are not draws. All three winners of horizontal-distance contests are sector-based. These findings confirm the visual impression from Fig. 11.1 that sector-based long-only optimal portfolios are less risky than their counterparts using factor components. Less expectedly, Panel B indicates that the same holds true for long-short portfolios in the full sample period and during crises. The result is reversed for non-crisis periods when factor investing manages to significantly mitigate market risk. When short sales are authorized, investing in factor components gives its full potential in enhancing expected returns and wins the three contests relying on the vertical distance. Overall, the winning style for long-only is sector investment and the winning style for long-short portfolios is factor investment. The left-hand side of Table 11.4 indicates that factors tend to enhance expected returns, while the right-hand side shows that sectors perform well in reducing portfolio volatility. Such a balanced overall outcome suggests that combining styles might generate attractive investment opportunities. The next section explores these innovative options.

5 Combination

The overwhelming success of factor investing has overshadowed other investment styles, especially from the perspective of investors who wish to benefit from diversification potential. The previous section of this chapter shows that sector investing is competitive in specific circumstances, including in the presence of long-only restrictions and high risk aversion. An additional advantage of sector investing stems from its quasi-passive structure, which is more cost-effective than factor investing (Novy-Marx and Velikov 2016). On the other hand, factor investing delivers significant risk premia and short positions help to hedge, at least partially, risks that investors wish to avoid. For all these reasons, we now explore portfolios that optimally combine sectors and factor components. The resulting efficient frontiers are presented in Fig. 11.2.

Does mixing the two styles improve on the winner of the previous contest? The answer to this question depends on the situation. Figures 11.2e and 11.2f reveal that the gain is modest, especially with respect to factor investing, in the non-crisis cases, regardless of whether short-selling is allowed. Figure 11.2c indicates that, in a long-only context, sectors alone can be sufficient to handle crises. By contrast, Fig. 11.2d suggests that combining sectors and factor components in long-short portfolios might be a smart strategy in order to prepare for financial crises and recessions. The full sample graphs deliver intermediate results. Figure 11.2a shows that the combination is especially valuable to investors with medium levels of risk aversion.

Table 11.3 shows that the optimally combined portfolios always beat the market index, both vertically (higher expected return for same volatility) and horizontally (lower volatility for same expected return) at the 1% level. In 10 out of 12 cases, the result derives from the winner’s performance in Table 11.2. In the case of long-short portfolios (Panel B), the distance obtained for mixed portfolios is always strictly larger than the one computed for the previous winner. These results suggest that investors aiming to beat the market are better off with combined portfolios than single-style ones. For long-only portfolios, the figures are less clear-cut. During crises, the optimally combined portfolios are made up of sectors only; factor components not only perform poorly, they fail to bring any diversification benefit. Yet, the full sample and non-crisis results suggest that combining the two styles leads to notable improvements in terms of increasing the distances from the market index.

Table 11.5 compares the test outcomes for the mixed portfolios with those of the winner of the previous contest presented in Table 11.2. First, significant scores are obtained under any circumstances, including for long-only portfolios during non-crisis periods where tests using the vertical distance show neither sector investing nor factor investing was able to beat the market on expected returns (see Table 11.4). The results from Panel B reveal that the added value from the inclusion of sectors into optimal portfolios originally made up of factor components comes from increasing the dominance scores with respect to the market expected returns. The figures suggest that the most spectacular impact takes place during crises: the vertical distance to the market expected return in crises passes from 0.0234 (or 0.28% per annum) for factor components alone to 0.0449 (or 0.59% per annum) for the “sector + factor” investing combination.

Table 11.6 presents the compositions of the “sector + factor” portfolios, which beat the market. It shows the fit between factor components and sectors. Over the full sample and the non-crisis periods, vertical long-only portfolios mainly include factor components, while horizontal long-only factors have a heavier loading on sectors. These results are consistent with the risk reduction associated with sector investment, as opposed to the return enhancement triggered by factor components. Our results also confirm the previous finding that factor components do not help in beating the market in long-only portfolios during crisis periods, both vertically (in order to achieve higher expected returns) and horizontally (to reach lower volatility). For the long-short portfolios reported in Panel B, both the vertical and the horizontal portfolios include unrealistically high short exposures. Even so, differences emerge between the loadings of sectors and the factor components. Both the long and the short exposures of factor components are impressive, but the net exposure (long + short) is always positive. By contrast, the net exposure of sectors is positive in non-crisis periods and negative during crises. The figures in Panel B confirm that all the efficient long-short portfolios (i.e. those that permit short-selling) have long and short exposures both to sectors and to factor components. In Panel A, by contrast, 50% of the portfolios include assets of one category only (see the detailed compositions in Appendix A).

6 Discussion and Conclusion

From a theoretical perspective, sector investing and factor investing rely on different logics. On the one hand, industrial sectors were originally built to diversify risks across economic activities. Risk reduction stemming from diversification is a benefit that is especially needed in crisis periods when volatility spikes. On the other hand, the advantage of factor components lies in being able to earn the risk premia they were built to deliver (Brière and Szafarz 2015). Our first results confirm that both styles keep their promises and produce the expected outcomes. Regarding the factor/sector contest, our findings suggest that factor investing performs better when short-selling is authorized. By contrast, sector investing outperforms its competitor when short sales are forbidden. Overall, factor investing is riskier than sector investing as a direct consequence of the obvious: capturing risk premia primarily means taking more risks (see the volatilities reported in Table 11.2). In addition, sector investing has superior diversification potential, and factors exhibit large and positive extreme correlations (Christoffersen and Langlois 2013).

Next, guided by the hope that combining the two styles would have a positive effect on the financial performance, we mixed them and then observed the mean-variance performance of the resulting portfolios. Our results show that the gain is especially visible for long-short portfolios, where the already good performance of factor investing is enhanced by including lower-risker sectors. The benefits are higher during crisis periods, suggesting that the diversification benefits brought by sectors play their part very well when needed. This favorable outcome in troubled times, however, fails when short sales are prohibited. For long-only portfolios, factors can still enhance returns by delivering alphas with respect to the market during quiet times, but they lose their attractive properties for hedging against crises. By showing that industry-based portfolios can help asset managers reduce factor-specific risks, this chapter offers a strategy to bypass short-sale restrictions in factor investing using industry-based portfolios. This is because several industries have negative loadings on factors (Chou et al. 2012), implying that a well-chosen combination of sectors could shrink the loadings on the factors. Thus, sector-based investment strategies could help long-only investors achieve better risk-return properties for their portfolios. Further research could assess in a general setting how efficiently industry-based portfolios hedge investor against performance losses associated with short-sale restrictions.

Notes

- 1.

The way individual stocks are grouped into industrial sectors raises specific issues (Vermorken et al. 2010).

- 2.

Brière and Szafarz (2017) examine intermediate situations such as the 130/30 and the case where only the market index can be shorted.

- 3.

- 4.

In Brière and Szafarz (2015), we consider crises and bear periods separately.

- 5.

In fact, t-tests fail to detect any significant differences among means, while some differences in variances are statistically significant.

References

Ang, A. (2014). Asset management—A systematic approach to factor investing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bae, J. W., Elkhami, R., & Simutin, M. (2016). The best of both worlds: Accessing emerging economies by investing in developed markets. SSRN Working Paper 264475.

Barroso, P., & Santa-Clara, P. (2015). Momentum has its moments. Journal of Financial Economics, 116(1), 111–120.

Basak, G., Jagannathan, R., & Sun, G. (2002). A direct test for the mean-variance efficiency of a portfolio. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 26(7–8), 1195–1215.

Brière, M., & Szafarz, A. (2015). Factor investing: Risk premia vs. diversification benefits. SSRN Working Paper 2615703.

Brière, M., & Szafarz, A. (2017). Factor investing: The rocky road from long-only to long-short. In E. Jurczenko (Ed.), Factor Investing. Elsevier, 25–45.

Brière, M., Drut, B., Mignon, V., Oosterlinck, K., & Szafarz, A. (2013). Is the market portfolio efficient? A new test of mean-variance efficiency when all assets are risky. Finance, 34(1), 7–41.

Carhart, M. M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. Journal of Finance, 52(1), 57–82.

Chou, P. H., Ho, P. H., & Ko, K. C. (2012). Do industries matter in explaining stock returns and asset-pricing anomalies? Journal of Banking and Finance, 36(2), 355–370.

Christoffersen, P., & Langlois, H. (2013). The joint dynamics of equity market factors. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 48(5), 1371–1404.

Daniel, K. D., & Moskowitz, T. J. (2016). Momentum crashes. Journal of Financial Economics, 122(2), 221–224.

Ehling, P., & Ramos, S. B. (2006). Geographic versus industry diversification: Constraints matter. Journal of Empirical Finance, 13, 396–416.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1992). The cross-section of expected stock returns. Journal of Finance, 47(2), 427–465.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2015). A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics, 116(1), 1–22.

Goetzmann, W. N., Li, L., & Rouwenhorst, K. G. (2005). Long-term global market correlations. Journal of Business, 78(1), 1–38.

Heston, S. L., & Rouwenhorst, K. G. (1994). Does industrial structure explain the benefits of international diversification? Journal of Financial Economics, 36(1), 3–27.

Lewellen, J., Nagel, S., & Shanken, J. (2010). A skeptical appraisal of asset pricing tests. Journal of Financial Economics, 96(2), 175–194.

Novy-Marx, R., & Velikov, M. (2016). A taxonomy of anomalies and their trading cost. Review of Financial Studies, 29(1), 104–147.

Sharpe, W. F. (1992). Asset allocation: Management style and performance measurement. Journal of Portfolio Management, 18(2), 7–19.

Vermorken, M., Szafarz, A., & Pirotte, H. (2010). Sector classification through non-Gaussian similarity. Applied Financial Economics, 20(11), 861–878.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Vafa Ahmadi, Alexander Attié, Narayan Bulusu, Eric Bouyé, Jacob Bjorheim, Tony Bulger, Joachim Coche, Melchior Dechelette, Pierre Collin-Dufresne, Arnaud Faller, Pascal Farahmand, Tom Fearnley, Nicolas Fragneau, Campbell Harvey, Antti Ilmanen, Jianjian Jin, Theo Kaitis, Yvan Lengwiler, Christian Lopez, Gabriel Petre, Bruce Phelps, Sudhir Rajkumar, Alejandro Reveiz, Francisco Rivadeneyra, Mihail Velikov, and the participants of the Sixth Joint BIS, World Bank, Bank of Canada Public Investors Conference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Brière, M., Szafarz, A. (2018). Factors and Sectors in Asset Allocation: Stronger Together?. In: Bulusu, N., Coche, J., Reveiz, A., Rivadeneyra, F., Sahakyan, V., Yanou, G. (eds) Advances in the Practice of Public Investment Management. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90245-6_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90245-6_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-90244-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-90245-6

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)