Abstract

Multifactor funds, which offer risk factor diversification, have several appealing characteristics. They enable investing in factors, which has become a typical way to enhance a portfolio’s long-term risk-adjusted return; they provide exposure to more than one factor, which enables diversification; and they offer these benefits neatly packaged in one product. What’s not to like? Their performance. Although their track record is limited, the current evidence on multifactor funds targeting the US, global, international, and emerging markets shows that these products have largely failed to outperform market-wide, cap-weighted indexes, or low-cost ETFs that track them, in terms of return, risk-adjusted return, and downside protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diversifying the equity slice of a portfolio across companies, sectors, and countries has been widely accepted by academics and practitioners for a long time; diversifying across equity risk factors, on the other hand, has been proposed more recently. Similarly, investing in individual factors, such as style or size, has a long history; investing in a single product that aims to provide a diversified exposure to several factors, however, is a far more recent development. The ultimate goal of this article is to assess the performance of these products, usually referred to as multifactor funds.

There is an ongoing debate on the relative merits of diversifying portfolios either across asset classes or across risk factors. Although that debate is related to the main issue addressed in this article, the focus here is narrower, on just one asset class (stocks) and on the different ways to obtain diversification within that slice of the portfolio. Importantly, exposure to the whole stock market, with each individual stock weighed by its relative market cap, can be currently obtained through index funds or ETFs at a negligible cost. Hence, investing in only some of those stocks, or investing in all of them using weights unrelated to price, or both, has a high bar to clear; whether multifactor funds clear that bar is at the heart of the discussion in this article.

More precisely, the performance of multifactor funds is evaluated here relative to the performance of market-wide, cap-weighted indexes of the US, global, international, and emerging markets. Although these products have a relatively limited history, the evidence so far shows that multifactor funds have been largely a disappointment, particularly in the US. This conclusion does not change if the performance of these products is evaluated relative to market-wide, cap-weighted, investable ETFs rather than relative to non-investable indexes.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. “The issue” section provides a brief history of factor investing, as well as a brief introduction to multifactor funds; “The evidence” section discusses the evidence, based on a sample of over 50 multifactor funds, with more than half of them targeting the US market; and “The assessment” section provides an assessment. An appendix with tables concludes the article.

The issue

A very brief history of factors

A factor can be defined as the spread between the return on one set of securities, systematically and clearly defined, versus another (Asness 2016).Footnote 1 The market factor of the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), developed by Sharpe (1964), Lintner (1965), Mossin (1966), and Treynor (1962) is only the first of many other factors that were introduced over time. Ross (1976) proposed an alternative to the CAPM, the arbitrage pricing theory (APT), which argues that stock returns are determined not by one but by many factors, although the theory does not specify how many or which ones.

Basu (1977) and Banz (1981) are widely credited with being the seminal articles on the outperformance of value stocks over growth stocks and small caps over large caps. Following these pioneering insights, Fama and French (1993) added the style and size factors to the CAPM, thus giving birth to the three-factor model.Footnote 2 Asness et al (2015) provide a good overview of the literature on the style factor, and Alquist et al. (2018) do the same for the size factor.Footnote 3

Less discussed in the academic literature but enthusiastically embraced by asset management companies is the fact that, prior to Basu (1977) and Banz (1981), Haugen and Heins (1972, 1975) showed that low-volatility stocks outperform high-volatility stocks, a pattern that eventually became known as the volatility factor. Consistent with those findings, Clarke et al (2006) showed that minimum-variance portfolios have about three-fourths the volatility of the market portfolio, with the risk reduction not coming at the expense of lower returns; and Blitz and van Vliet (2007) showed that portfolios of low-volatility (high-volatility) stocks outperform (underperform) the market in terms or risk-adjusted return.

Jegadeesh and Titman (1993) showed that buying stocks that performed well in the recent past (winners) and selling stocks that performed poorly in the recent past (losers) leads to significant abnormal returns, a pattern that became known as the momentum factor. Carhart (1997) added the momentum factor to the Fama-French three-factor model, thus giving birth to the four-factor model.

Titman et al (2004) showed that there is a negative relationship between capital investment and returns, with companies that substantially increase capital investments obtaining lower returns over the subsequent five years; this pattern eventually became known as the investment factor. Novy-Marx (2013) showed that profitability, measured by the ratio of a company’s gross profit to assets, is positively related to stock returns and explains the latter just as well as the book-to-market ratio; this pattern eventually became known as the quality factor. Fama and French (2015) added the investment and quality factors to their three-factor model (albeit ignoring the momentum factor), thus giving birth to the five-factor model.

The proliferation of empirical regularities uncovered in multiple studies led Cochrane (2011) to refer to them as a ‘zoo’ of factors. The explanatory power of factors, on the other hand, led researchers to ask whether the standard way of diversifying portfolios, across asset classes, could be improved upon by diversifying portfolios across risk factors. Page and Taborsky (2011), for example, show that correlations across factors are lower than those across asset classes and argue that risk factor diversification is superior to asset class diversification.Footnote 4

Idzorek and Kowara (2013), however, formally show that neither approach can be inherently superior to the other. In fact, they argue that the presumed superiority of risk factor diversification over asset class diversification typically follows from an apples-to-oranges comparison; in an apples-to-apples comparison, they show that neither approach can outperform the other. They also argue that risk factor diversification is not a macro-consistent strategy, and that most institutional investors would be reluctant to implement the extreme leveraged positions implied by it.

Asness (2016) argues that not all factors are the result of data mining, and the excess return of those that are not should be expected to persist in future; among them he includes the style, size, momentum, and quality factors. He also cautions against trying to time these factors, suggesting instead to focus on those expected to deliver long-term outperformance, to access them in a cost-effective way, to diversify across them, and to maintain those exposures with little variance over time.

The proliferation and popularity of factors led Morningstar to think beyond their Morningstar Style Box introduced in the early 1990s, which splits funds into two dimensions, valuation (growth, core, and value) and market capitalization (large, medium, and small caps). Acknowledging the importance of other factors the company recently introduced the Morningstar Factor Profile, which adds five additional variables to the style box, so that funds are evaluated on the basis of their exposure to the style, size, quality, momentum, volatility, liquidity, and yield factors; see, for example, Johnson (2020).

Finally, note that weighting schemes and exposure to factors are related but different concepts.Footnote 5 In fact, the former can be used to obtain the latter. Consider, for example, a strategy that equally weights the 500 stocks in the S&P 500. Almost by definition, such strategy will expose investors to the size factor given that, relative to the market-cap-weighted S&P 500, it would reduce the weight of the largest companies and increase the weight of the smallest companies. In addition, the periodic rebalancing to equal weights would imply selling the companies whose price has (relatively) increased and buy those whose price has (relatively) decreased, thus exposing investors to the value factor.

Multifactor funds

It is currently widely accepted by both academics and practitioners that stock returns are driven by factors; that some factors have been more thoroughly tested and are more reliable than others; and that exposure to those factors can be expected to enhance long-term risk-adjusted returns. Perhaps for these reasons, cap-weighted funds of value and small-cap stocks have existed for many years; smart beta funds, however, are a more recent development.Footnote 6

To be sure, there is no consensus definition of smart beta in the industry. Some would claim that a cap-weighted fund of value stocks is a smart beta product, some others would disagree. Arnott (2014) argues that a smart beta strategy needs to break the link between the price of an asset and its weight in the portfolio, seeks to earn excess returns over a cap-weighted benchmark, and retains most of the positive attributes of passive indexing.

Multifactor funds are generally considered smart beta products. As such, they aim to provide investors with rules-based active management, charging lower fees than actively managed funds, albeit substantially higher fees than passively managed index funds or ETFs. They also aim to provide investors with a diversified exposure to well-known factors, such as style, size, quality, momentum, and volatility, which are the most widely accepted by academics and practitioners.

Because many products provide direct or indirect access to the style and size factors, the focus here is on those that provide broader diversification, with exposure to at least three factors. Additionally, the focus is on products that are explicitly marketed as multifactor funds, either by their labeling or by clearly highlighting a diversified exposure to factors in the product information. An example of the former is the iShares MSCI U.S. Multifactor ETF; an example of the latter is the Goldman Sachs ActiveBeta U.S. Large Cap Equity ETF, which “aims to acquire stocks based on four well-established attributes of performance: good value, strong momentum, high quality and low volatility.”Footnote 7

The evidence

Data

The sample consists of 56 multifactor funds that resulted from filtering the products available in this category. The screens applied selected products domiciled in the US and available to US investors; with at least three years of monthly data through March, 2022; with at least $10 million of net assets as of March, 2022; and as already mentioned, that offer exposure to at least three factors and are explicitly marketed as multifactor funds.

Exhibit A1 in the appendix lists alphabetically by product name all the funds in the sample, their ticker, net assets, expense ratio, and inception date. The average fund in the sample had net assets of $733 million (biased upward by GSLC’s assets of $13.7 billion, by far the largest in the sample) and an expense ratio of 33 basis points, both as of the end of March, 2022. More than half of the funds (32) target the US market; 2 target the global market; 13 target the international (global excluding US) market; and 9 target emerging markets. Of the 56 funds in the sample, 54 are structured as ETFs.

The funds in the sample with the oldest inception date are SPDR MSCI EAFE StrategicFactors ETF and SPDR MSCI Emerging Markets StrategicFactors ETF (Jun/4/2014) and that with the newest is BlackRock U.S. Equity Factor Rotation ETF (Mar/19/2019). The funds with the largest sample size have 93 observations (monthly returns) and that with the smallest has 36; the average fund in the sample has 66 observations. All returns are monthly, from the end of the first month of trading and through Mar/2022, and in dollars.

US multifactor funds: risk and return

Exhibit 1 focuses on the 32 multifactor funds that target the US market, with the S&P 500 as its benchmark (B). For the series of monthly returns available for each fund the exhibit shows the fund’s ticker, number of observations (T), mean compound return (MR), volatility (SD), risk-adjusted return (RAR), and risk-adjusted performance (RAP), the latter both in monthly and in annualized terms. The last three rows of the exhibit show averages across all funds (Avg), as well as across all the funds that outperformed (Avg-O) and underperformed (Avg-U) the S&P 500, based on the different variables considered in the exhibit.

Exhibit 1: US multifactor funds vs. S&P 500

This exhibit shows the ticker, number of observations (T), mean compound return (MR), volatility (SD), risk-adjusted return (RAR), and risk-adjusted performance (RAP) for US multifactor funds. The last three rows show averages across all the funds (Avg), as well as across all the funds that outperformed (Avg-O) and underperformed (Avg-U) the benchmark (B), which is the S&P 500. MR, SD, and RAR are monthly figures; all figures but T and RAR in %.

Ticker | T | MR | SD | RAR | RAP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Monthly | Annualized | ||||||||||

Fund | B | Fund | B | Fund | B | Fund | B | Fund | B | ||

AUSF | 43 | 0.83 | 1.19 | 5.95 | 5.16 | 0.170 | 0.256 | 0.88 | 1.32 | 11.1 | 17.1 |

DEUS | 76 | 0.94 | 1.19 | 4.59 | 4.20 | 0.228 | 0.304 | 0.96 | 1.28 | 12.1 | 16.4 |

DYNF | 36 | 1.13 | 1.45 | 5.00 | 5.06 | 0.251 | 0.313 | 1.27 | 1.58 | 16.3 | 20.7 |

FCTR | 44 | 1.19 | 1.24 | 6.03 | 5.11 | 0.227 | 0.267 | 1.16 | 1.37 | 14.8 | 17.7 |

FLQL | 59 | 1.13 | 1.25 | 4.32 | 4.56 | 0.283 | 0.297 | 1.29 | 1.35 | 16.6 | 17.5 |

FLQM | 59 | 1.08 | 1.25 | 5.00 | 4.56 | 0.241 | 0.297 | 1.10 | 1.35 | 14.0 | 17.5 |

FLQS | 59 | 0.71 | 1.25 | 5.35 | 4.56 | 0.161 | 0.297 | 0.73 | 1.35 | 9.2 | 17.5 |

FSMD | 37 | 0.99 | 1.47 | 5.94 | 4.99 | 0.198 | 0.319 | 0.99 | 1.59 | 12.5 | 20.9 |

GSLC | 78 | 1.19 | 1.27 | 4.14 | 4.22 | 0.307 | 0.321 | 1.30 | 1.36 | 16.7 | 17.5 |

GSSC | 57 | 0.85 | 1.26 | 5.30 | 4.63 | 0.188 | 0.294 | 0.87 | 1.36 | 11.0 | 17.6 |

JHML | 78 | 1.19 | 1.27 | 4.42 | 4.22 | 0.291 | 0.321 | 1.23 | 1.36 | 15.8 | 17.5 |

JHMM | 78 | 1.06 | 1.27 | 4.90 | 4.22 | 0.242 | 0.321 | 1.02 | 1.36 | 13.0 | 17.5 |

JHSC | 52 | 0.62 | 1.19 | 6.17 | 4.84 | 0.133 | 0.270 | 0.64 | 1.31 | 8.0 | 16.8 |

JPME | 70 | 1.02 | 1.26 | 4.73 | 4.24 | 0.239 | 0.319 | 1.01 | 1.35 | 12.9 | 17.5 |

JPSE | 64 | 0.95 | 1.29 | 5.74 | 4.39 | 0.195 | 0.316 | 0.86 | 1.39 | 10.8 | 18.0 |

JPUS | 78 | 1.08 | 1.27 | 4.35 | 4.22 | 0.270 | 0.321 | 1.14 | 1.36 | 14.6 | 17.5 |

LRGF | 83 | 0.86 | 1.10 | 4.26 | 4.21 | 0.223 | 0.283 | 0.94 | 1.19 | 11.9 | 15.2 |

MFUS | 54 | 1.04 | 1.24 | 4.62 | 4.76 | 0.248 | 0.285 | 1.18 | 1.36 | 15.1 | 17.6 |

OMFL | 52 | 1.32 | 1.19 | 5.32 | 4.84 | 0.274 | 0.270 | 1.33 | 1.31 | 17.1 | 16.8 |

OMFS | 52 | 0.86 | 1.19 | 6.58 | 4.84 | 0.163 | 0.270 | 0.79 | 1.31 | 9.9 | 16.8 |

OUSA | 80 | 0.91 | 1.12 | 3.90 | 4.27 | 0.252 | 0.285 | 1.08 | 1.22 | 13.7 | 15.6 |

OUSM | 63 | 0.69 | 1.28 | 5.15 | 4.42 | 0.161 | 0.311 | 0.71 | 1.38 | 8.9 | 17.8 |

PSC | 66 | 0.97 | 1.28 | 6.32 | 4.35 | 0.187 | 0.316 | 0.81 | 1.37 | 10.2 | 17.8 |

QLC | 78 | 1.03 | 1.27 | 4.38 | 4.22 | 0.258 | 0.321 | 1.09 | 1.36 | 13.9 | 17.5 |

QUS | 83 | 1.05 | 1.10 | 4.06 | 4.21 | 0.278 | 0.283 | 1.17 | 1.19 | 15.0 | 15.2 |

ROSC | 84 | 0.72 | 1.10 | 4.88 | 4.18 | 0.172 | 0.284 | 0.72 | 1.19 | 9.0 | 15.2 |

ROUS | 85 | 0.77 | 1.07 | 4.30 | 4.17 | 0.200 | 0.277 | 0.83 | 1.15 | 10.5 | 14.8 |

SMLF | 83 | 0.85 | 1.10 | 5.17 | 4.21 | 0.192 | 0.283 | 0.81 | 1.19 | 10.1 | 15.2 |

SQLV | 56 | 0.88 | 1.24 | 6.94 | 4.67 | 0.163 | 0.289 | 0.76 | 1.35 | 9.5 | 17.5 |

USMF | 57 | 1.00 | 1.26 | 4.56 | 4.63 | 0.243 | 0.294 | 1.13 | 1.36 | 14.4 | 17.6 |

VFMF | 49 | 0.76 | 1.20 | 5.59 | 4.89 | 0.165 | 0.270 | 0.81 | 1.32 | 10.2 | 17.1 |

VSMV | 57 | 1.08 | 1.26 | 4.02 | 4.63 | 0.289 | 0.294 | 1.34 | 1.36 | 17.3 | 17.6 |

Avg | 64 | 0.96 | 1.23 | 5.06 | 4.52 | 0.222 | 0.295 | 1.00 | 1.33 | 12.7 | 17.2 |

Avg-O | 1.32 | 1.19 | 5.32 | 4.84 | 0.274 | 0.270 | 1.33 | 1.31 | 17.1 | 16.8 | |

Avg-U | 0.95 | 1.23 | 5.05 | 4.51 | 0.220 | 0.296 | 0.99 | 1.33 | 12.5 | 17.2 | |

The MR columns of Exhibit 1 show that, as a group, multifactor funds underperformed the S&P 500 in terms of return, with the former returning 0.96% a month (12.2% annualized) and the latter 1.23% (15.8% annualized), for a substantial difference of 3.6% a year. Furthermore, the SD columns show that this underperformance came with higher risk, as evidenced by the monthly volatility of multifactor funds (5.06%, or 17.5% annualized) and that of the S&P 500 (4.52%, or 15.7% annualized), for an annual difference of 1.9%.

The exhibit also shows that only one of the 32 multifactor funds in the sample beat the S&P 500 in terms of return (OMFL), and it did so by 13 basis points (=1.32–1.19%) a month, or annualizing both figures and taking the difference, 1.8% a year. The other 31 multifactor funds underperformed the benchmark by 28 basis points (=0.95–1.23%) a month, or again annualizing both figures and taking the difference, 3.8% a year. In short, if the goal of multifactor funds is to enhance returns, they failed dramatically.

The RAR columns of Exhibit 1 show that assessing risk-adjusted returns instead of returns does not make multifactor funds look any better; as a group, these funds underperformed the S&P 500, as evidenced by a risk-adjusted return of 0.222 for the former and 0.295 for the latter.Footnote 8 Furthermore, it is again the case that only one of the 32 funds in the sample beat the S&P 500, and again the outperformer is OMFL. The risk-adjusted return of this fund (0.274) is less than 2% higher than that of the benchmark (0.270); on the other hand, as the last row of the exhibit shows, the RAR of the average underperforming fund (0.220) is nearly 26% lower than that of the benchmark (0.296). As was the case with returns, then, in terms of risk-adjusted returns only one of the 32 funds in the sample outperformed the S&P 500, and it did so by a far smaller margin than that of the rest of the funds that underperformed the benchmark.

Rather than testing for the statistical significance of the difference in risk-adjusted returns, the last four columns of Exhibit 1, and particularly the last two, which annualize the figures in the previous two columns, focus on economic significance. These four columns show a slight variation of the risk-adjusted performance metric introduced by Modigliani and Modigliani (1997), which converts risk-adjusted return figures, expressed in (unintuitive) return per unit of volatility, into risk-adjusted performance figures, which are more intuitively expressed in percent. More precisely, the risk-adjusted performance of fund i (RAPi) is given by

where RARi is the risk-adjusted return of fund i, obtained by dividing the fund’s arithmetic mean return by its volatility, and SDB is the volatility of the benchmark.Footnote 9

The last two columns of Exhibit 1 show that, as a group, multifactor funds underperformed the S&P 500 by 4.5% (=12.7–17.2%) a year on a risk-adjusted basis. Furthermore, the only fund in the sample that beat the benchmark (OMFL) did so by a risk-adjusted 0.3% (=17.1–16.8%) a year; the other 31 funds underperformed the benchmark by a risk-adjusted 4.7% (=12.5–17.2%) a year. Just as the magnitude of the outperformance seems small, that of the underperformance seems substantial. In short, US multifactor funds performed poorly relative to a market-wide, cap-weighted benchmark not just in terms of return but also in terms of risk-adjusted return.

US multifactor funds: other benchmarks

The previous assessment is based on the S&P 500 as a benchmark for the US market, which could be criticized on at least two grounds. First, it excludes a large number of stocks, tilting toward large-cap, growth-oriented companies; and second, like any benchmark, it excludes the cost of obtaining exposure to it. The first problem can be addressed by considering a broader benchmark, such as the Russell 3000; the second problem can be addressed by considering ETFs that aim to replicate the performance of the S&P 500 and the Russell 3000.

Exhibit 2 shows annualized RAPs for the 32 US multifactor funds in the sample relative to an ETF that tracks the performance of the S&P 500 (iShares Core S&P 500 ETF, IVV), the Russell 3000 index (R3000), and an ETF that tracks the performance of the Russell 3000 (iShares Russell 3000 ETF, IWV). The results for IVV are nearly identical to those discussed before for the S&P 500 as the benchmark, which should not be surprising given that IVV has a very low expense ratio (3 basis points); hence, replacing the non-investable S&P 500 by the investable IVV does not affect any of the conclusions already discussed.

Exhibit 2: US multifactor funds vs. other benchmarks

This exhibit shows the ticker and annualized RAP for 32 US multifactor funds and three different benchmarks: IVV, R3000, and IWV. The last two rows on the right half show averages across all the funds that outperformed (Avg-O) and underperformed (Avg-U) each benchmark. The benchmarks are specified in Exhibit A2 in the appendix. All figures in %.

Ticker | Fund | IVV | Fund | R3000 | Fund | IWV | Ticker | Fund | IVV | Fund | R3000 | Fund | IWV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

AUSF | 11.0 | 17.0 | 11.6 | 16.4 | 11.5 | 16.2 | MFUS | 15.0 | 17.5 | 15.7 | 17.0 | 15.6 | 16.8 |

DEUS | 12.1 | 16.4 | 12.6 | 16.1 | 12.6 | 15.9 | OMFL | 17.0 | 16.8 | 17.8 | 16.3 | 17.7 | 16.1 |

DYNF | 16.2 | 20.7 | 17.0 | 20.2 | 16.9 | 20.0 | OMFS | 9.8 | 16.8 | 10.3 | 16.3 | 10.2 | 16.1 |

FCTR | 14.7 | 17.6 | 15.5 | 17.1 | 15.4 | 16.9 | OUSA | 13.7 | 15.6 | 14.2 | 15.1 | 14.2 | 14.9 |

FLQL | 16.5 | 17.5 | 17.2 | 17.0 | 17.1 | 16.8 | OUSM | 8.9 | 17.8 | 9.3 | 17.3 | 9.2 | 17.1 |

FLQM | 13.9 | 17.5 | 14.6 | 17.0 | 14.4 | 16.8 | PSC | 10.1 | 17.7 | 10.6 | 17.4 | 10.5 | 17.2 |

FLQS | 9.1 | 17.5 | 9.5 | 17.0 | 9.5 | 16.8 | QLC | 13.8 | 17.5 | 14.4 | 17.1 | 14.4 | 16.9 |

FSMD | 12.4 | 20.8 | 13.0 | 20.2 | 12.9 | 20.0 | QUS | 14.9 | 15.2 | 15.5 | 14.8 | 15.5 | 14.6 |

GSLC | 16.7 | 17.5 | 17.4 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 16.9 | ROSC | 9.0 | 15.2 | 9.3 | 14.7 | 9.3 | 14.5 |

GSSC | 10.9 | 17.6 | 11.4 | 17.2 | 11.3 | 17.0 | ROUS | 10.5 | 14.7 | 10.9 | 14.3 | 10.8 | 14.1 |

JHML | 15.7 | 17.5 | 16.4 | 17.1 | 16.3 | 16.9 | SMLF | 10.1 | 15.2 | 10.5 | 14.8 | 10.4 | 14.6 |

JHMM | 12.9 | 17.5 | 13.5 | 17.1 | 13.4 | 16.9 | SQLV | 9.5 | 17.4 | 9.9 | 17.0 | 9.8 | 16.8 |

JHSC | 8.0 | 16.8 | 8.3 | 16.3 | 8.2 | 16.1 | USMF | 14.3 | 17.6 | 15.0 | 17.2 | 14.8 | 17.0 |

JPME | 12.8 | 17.5 | 13.4 | 17.2 | 13.3 | 17.0 | VFMF | 10.1 | 17.0 | 10.6 | 16.7 | 10.5 | 16.5 |

JPSE | 10.7 | 17.9 | 11.2 | 17.4 | 11.1 | 17.2 | VSMV | 17.2 | 17.6 | 18.0 | 17.2 | 17.8 | 17.0 |

JPUS | 14.5 | 17.5 | 15.2 | 17.1 | 15.1 | 16.9 | Avg-O | 17.0 | 16.8 | 17.2 | 16.5 | 17.1 | 16.3 |

LRGF | 11.8 | 15.2 | 12.3 | 14.8 | 12.3 | 14.6 | Avg-U | 12.5 | 17.2 | 12.5 | 16.8 | 12.4 | 16.6 |

The results are somewhat more encouraging when the Russell 3000, or an ETF that tracks it, is used for the assessment; in both cases, five of the 32 funds in the sample outperformed the benchmark (FLQL, GSLC, OMFL, QUS, and VSMV). And yet, as before, the magnitude of the differential performance is asymmetric; the five funds that delivered higher risk-adjusted return than the benchmark outperformed by a risk-adjusted 0.7–0.8% a year, whereas the remaining 27 funds that underperformed did so by 4.2–4.3% a year.Footnote 10

The fact that multifactor funds performed better when evaluated with respect to the Russell 3000 (or an ETF that tracks it) than they did with respect to the S&P 500 (or an ETF that tracks it) should not be surprising; over the sample period considered here, large/growth stocks, which the S&P 500 tilts toward, have considerably outperformed small/value stocks, which the Russell 3000 overweighs relative to the S&P 500.Footnote 11 That said, the performance of multifactor funds that target the US market has been mostly disappointing, in terms of both return and risk-adjusted return, particularly when evaluated with respect to the S&P 500, the market’s main benchmark.

US multifactor funds: downside protection

It is possible, albeit not entirely obvious from the funds’ marketing information, that multifactor funds do not really intend to outperform a broad benchmark in terms of return or risk-adjusted return; rather, they may offer risk factor diversification with the ultimate goal of mitigating the market’s downturns. Put differently, it is conceivable that their goal is to provide downside protection, particularly during severe downturns. To explore this possibility, Exhibit 4 reports the maximum drawdown (MD) over each fund’s sample period.

Exhibit 3: US multifactor funds: downside protection

This exhibit shows the maximum drawdown (MD) over the sample period for each of the 32 US multifactor funds in the sample. All figures in %.

Fund | MD | Fund | MD | Fund | MD | Fund | MD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

AUSF | − 31.6 | GSLC | − 19.2 | LRGF | − 22.9 | QUS | − 19.5 |

DEUS | − 27.3 | GSSC | − 26.5 | MFUS | − 23.9 | ROSC | − 34.0 |

DYNF | − 21.0 | JHML | − 22.2 | OMFL | − 21.9 | ROUS | − 22.1 |

FCTR | − 22.1 | JHMM | − 27.5 | OMFS | − 33.3 | SMLF | − 31.9 |

FLQL | − 20.8 | JHSC | − 32.0 | OUSA | − 20.2 | SQLV | − 40.5 |

FLQM | − 25.1 | JPME | − 29.1 | OUSM | − 28.7 | USMF | − 22.9 |

FLQS | − 31.7 | JPSE | − 33.6 | PSC | − 38.4 | VFMF | − 30.3 |

FSMD | − 29.3 | JPUS | − 26.0 | QLC | − 21.6 | VSMV | − 19.2 |

In most (but not all) cases, the drawdowns in the exhibit occurred during the Dec/2019–Mar/2020 period, coinciding with the global turmoil arising from the Covid-19 pandemic. The average drawdown across all the multifactor funds in the table was –26.8%; the S&P 500 and the Russell 3000, on the other hand, had drawdowns of –19.6% and –20.9% (almost respectively identical to those of the IVV and IWV ETFs), also during the Dec/2019–Mar/2020 period. In other words, far from mitigating the downside, multifactor funds fell, on average, 7.2% more than did the S&P 500, and 5.9% more than did the Russell 3000.

Of the 32 US multifactor funds in the sample, only three (GSLC, QUS, and VSMV) had marginally lower drawdowns, in absolute value, than the S&P 500’s 19.6%, dropping 19.2%, 19.5%, and 19.2; hence, these three funds had an average drawdown of − 19.3%, outperforming the S&P 500 by 0.3%. The other 29 funds had an average drawdown of − 27.5%, thus underperforming the S&P 500 by 7.9%. Furthermore, five funds (FLQL, GSLC, OUSA, QUS, and VSMV) had drawdowns slightly lower, again in absolute value, than the Russell 3000’s 20.9%, dropping − 20.8%, − 19.2%, − 20.2%, − 19.5%, and − 19.2%; thus, these five funds had an average drawdown of − 19.8%, outperforming the Russell 3000 by 1.1%. The other 27 funds had an average drawdown of − 28.1%, thus underperforming the Russell 3000 by 7.2%.

As was the case with return and risk-adjusted return, in terms of downside protection few multifactor funds outperformed the broad benchmarks, and they did so by a very small margin; the many more funds that underperformed the benchmarks, however, did so by a much larger margin. In short, if the goal of multifactor funds is to provide investors with downside protection, particularly during severe downturns, they also failed dramatically.

Robustness: other regions

Although multifactor funds are a relatively new development and their history is limited, the current available evidence is far from encouraging; in general, neither these products outperformed widely available, low-cost, market-wide US ETFs (or their underlying indexes) in terms of return or risk-adjusted return nor did they protect investors against severe downturns. Have multifactor funds that target other regions been more successful? Exhibit 4 aims to answer this question.

Exhibit 4: multifactor funds: other regions: returns and risk-adjusted performance

This exhibit shows the ticker, number of observations (T), annualized return (AR), and annualized risk-adjusted performance (RAP) for multifactor funds targeting global, international, and emerging markets, as well as benchmarks (indexes and ETFs) for all regions. The last two rows show averages across all the funds that outperformed (Avg-O) and underperformed (Avg-U) each benchmark. The benchmarks are specified in Exhibit A2 in the appendix. All figures but T in %.

Benchmark: Indexes | Benchmark: ETFs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

AR | RAP | AR | RAP | ||||||

Global | T | Fund | ACWI | Fund | ACWI | Fund | ACWI | Fund | ACWI |

ACWF | 82 | 7.8 | 10.0 | 8.7 | 11.2 | 7.8 | 9.6 | 8.5 | 10.7 |

FLQG | 69 | 11.1 | 13.1 | 13.1 | 14.3 | 11.1 | 12.6 | 12.9 | 13.7 |

International | Fund | ACWI ex-US | Fund | ACWI ex-US | Fund | ACWX | Fund | ACWX | |

DEEF | 76 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 8.6 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 7.7 |

DWMF | 43 | 3.2 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 7.6 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 6.8 |

FDEV | 37 | 5.9 | 8.0 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 8.5 |

FLQH | 69 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 12.3 | 9.8 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 12.0 | 8.9 |

GSIE | 76 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 7.9 | 7.7 |

INTF | 82 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 5.3 | 5.6 |

ISCF | 82 | 7.3 | 5.3 | 8.0 | 6.4 | 7.3 | 4.5 | 7.7 | 5.6 |

JHMD | 63 | 7.2 | 8.5 | 8.4 | 9.6 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 8.3 | 8.9 |

JPIN | 88 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 5.7 |

MFDX | 54 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 5.6 |

PQIN | 39 | 8.2 | 10.7 | 9.9 | 12.2 | 8.2 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 11.1 |

QEFA | 93 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 6.3 | 4.6 |

RODM | 85 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 5.7 |

Emerging | Fund | EMI | Fund | EMI | Fund | IEMG | Fund | IEMG | |

EMGF | 75 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 8.5 | 8.4 | 9.9 | 9.8 |

FDEM | 37 | 2.0 | 5.5 | 3.8 | 7.2 | 2.0 | 5.6 | 3.7 | 7.3 |

FLQE | 69 | 4.3 | 8.4 | 6.1 | 9.8 | 4.3 | 7.8 | 6.2 | 9.2 |

GEM | 78 | 7.1 | 8.6 | 8.8 | 10.0 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 8.7 | 9.5 |

JHEM | 41 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 10.1 | 9.7 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 10.2 | 9.7 |

JPEM | 86 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 4.2 | 5.0 | 5.7 | 6.4 |

MFEM | 54 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 5.8 | 5.1 |

QEMM | 93 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 4.9 |

ROAM | 85 | 1.5 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 6.3 | 1.5 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 5.9 |

Avg-O | 6.2 | 5.4 | 8.2 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 5.7 | 8.0 | 7.0 | |

Avg-U | 5.7 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 8.7 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 8.1 | |

The exhibit summarizes the annualized return (AR) and annualized risk-adjusted performance (RAP) of 24 multifactor funds, 2 that target the global market, 13 that target the international (global excluding US) market, and 9 that target emerging markets. The performance of each of these funds is evaluated with respect to a representative index, namely, the MSCI ACWI for global funds, the MSCI ACWI excluding US for international funds, and the MSCI EMI for emerging market funds. As before, performance is evaluated also with respect to investable ETFs, namely, ACWI for global funds, ACWX for international funds, and IEMG for emerging market funds. (See details of all benchmarks in Exhibit A2 in the appendix.)

As the top panel of the exhibit shows, the two global funds in the sample underperformed the benchmark indexes and ETFs in terms of both return and risk-adjusted return. The middle panel, in turn, shows that two of the 13 international funds outperformed the benchmark index in terms of return (ISCF and QEFA), and four did so in terms of risk-adjusted return (FLQH, ISCF, QEFA, and RODM); if the evaluation is based on an investable ETF as a benchmark instead, then six funds outperformed the benchmark in terms of both return and risk-adjusted return (FLQH, GSIE, ISCF, MFDX, QEFA, and RODM). Finally, the bottom panel shows that two out of nine emerging market funds outperformed the benchmark index in terms of return and risk-adjusted return (JHEM and MFEM), and three funds outperformed the benchmark ETF, also in terms of return and risk-adjusted return (EMGF, JHEM, and MFEM).

Importantly, the same asymmetry observed for US funds is observed for funds in global, international, and emerging markets. In other words, the few multifactor funds that outperform the broad benchmarks do so by a small margin, and the many more that underperform do so by a much larger margin. More precisely, considering all 24 funds in Exhibit 4, and focusing on indexes as benchmarks, the funds that outperformed did so by an annual difference of 0.8% (=6.2–5.4%) in terms of return and 1.0% (=8.2–7.2%) in terms of risk-adjusted performance, whereas those that underperformed did so by an annual difference of 1.6% (=5.7–7.3%) in terms of return and 1.5% (=7.2–8.7%) in terms of risk-adjusted performance. The results are very similar if ETFs, instead of indexes, are used as benchmarks.

Although multifactor funds seem to have been marginally more successful targeting markets other than the US, their overall performance in terms of return and risk-adjusted return is far from inspiring. Have they at least provided investors with downside protection, particularly during severe downturns? To answer this question, Exhibit 5 reports the maximum drawdown over the sample period of each multifactor fund in global, international, and emerging markets, as well as the maximum drawdown of all relevant benchmark indexes and ETFs.

Exhibit 5: Multifactor funds: other regions: downside protection

This exhibit shows the maximum drawdown over the sample period for each fund and benchmark. The benchmarks are specified in Exhibit A2 in the appendix. All figures in %.

International | Fund | ACWI ex-US | ACWX | Global | Fund | ACWI | ACWI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

DEEF | − 25.7 | − 23.5 | − 24.3 | ACWF | − 23.2 | − 21.3 | − 21.0 |

DWMF | − 18.2 | − 23.3 | − 23.3 | FLQG | − 20.6 | − 21.3 | − 21.0 |

FDEV | − 19.0 | − 23.3 | − 23.3 | ||||

FLQH | − 16.9 | − 23.5 | − 24.3 | Emerging | Fund | EMI | IEMG |

GSIE | − 23.5 | − 23.5 | − 24.3 | EMGF | − 31.2 | − 28.1 | − 30.1 |

INTF | − 29.3 | − 23.5 | − 24.3 | FDEM | − 24.5 | − 23.6 | − 24.7 |

ISCF | − 29.4 | − 23.5 | − 24.3 | FLQE | − 30.3 | − 28.1 | − 30.1 |

JHMD | − 25.1 | − 23.5 | − 24.3 | GEM | − 28.6 | − 28.1 | − 30.1 |

JPIN | − 26.0 | − 23.5 | − 24.3 | JHEM | − 25.8 | − 23.6 | − 24.7 |

MFDX | − 24.9 | − 23.5 | − 24.3 | JPEM | − 32.7 | − 28.1 | − 30.1 |

PQIN | − 23.2 | − 23.3 | − 23.3 | MFEM | − 33.9 | − 28.1 | − 30.1 |

QEFA | − 20.0 | − 23.5 | − 24.3 | QEMM | − 27.7 | − 29.4 | − 30.1 |

RODM | − 25.0 | − 23.5 | − 24.3 | ROAM | − 36.1 | − 28.1 | − 30.1 |

Considering all 24 funds in the exhibit, and focusing on indexes as benchmarks, the average drawdown of the seven funds that outperformed the benchmarks was − 20.8%, and that of the benchmarks was − 23.9%, for an average outperformance of 3.1%. On the other hand, the average drawdown of the 17 funds that underperformed the benchmarks was − 28.0%, and that of the benchmarks was − 25.0%, for an average underperformance of 3.0%. The results are slightly better for multifactor funds if ETFs, instead of indexes, are used as benchmarks.Footnote 12 Therefore, it does remain the case that more multifactor funds underperformed than outperformed the benchmarks, but in this case the asymmetry in the margin of gain or loss slightly favors the outperformers.

Further discussion

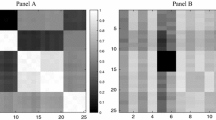

The results discussed in the previous four sections vary a little from one benchmark to another, and from the US to other markets, but the big picture seems rather clear: Multifactor funds have been largely a disappointment. All things considered, broadly diversified, low-cost index funds and ETFs, widely available to all investors, outperformed the more costly risk factor diversification provided by multifactor funds. Exhibit 6 considers all the funds and benchmarks in the sample and aims to summarize the main results discussed in this article.Footnote 13

Exhibit 6: All funds and benchmarks: summary

This exhibit shows the annualized return (AR), annualized volatility (SD), annualized risk-adjusted performance (RAP), and maximum drawdown (MD) across all the funds and benchmarks in the sample, including four benchmarks for the US (BUS). The benchmarks are specified in Exhibit A2 in the appendix. All figures in %.

AR | SD | RAP | MD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fund | B | Fund | B | Fund | B | Fund | B | |

BUS : S&P 500 | 9.4 | 11.9 | 16.3 | 15.6 | 10.4 | 13.3 | − 26.4 | − 21.8 |

BUS : R3000 | 9.4 | 11.6 | 16.3 | 16.0 | 10.7 | 13.0 | − 26.4 | − 22.5 |

BUS : IVV | 9.4 | 11.7 | 16.3 | 15.5 | 10.3 | 13.0 | − 26.4 | − 22.2 |

BUS : IWV | 9.4 | 11.2 | 16.3 | 15.8 | 10.5 | 12.7 | − 26.4 | − 22.9 |

Average | 9.4 | 11.6 | 16.3 | 15.7 | 10.5 | 13.0 | − 26.4 | − 22.3 |

Difference | − 2.2 | 0.6 | − 2.5 | − 4.0 | ||||

As the last two lines of the exhibit show, the average multifactor fund in the sample delivered an annualized return (AR) of 9.4%, 2.2% per year lower than that of the average benchmark considered (11.6%). Importantly, this difference in return cannot be fully, or even largely, attributed to the cost of multifactor funds, which at the end of March 2022, had an average expense ratio of 33 basis points. Nor can it be explained by differences in risk, at least if the latter is quantified with volatility; the annualized volatility (SD) of multifactor funds was 16.3% and that of the benchmarks was 15.7%, thus making these funds 0.6% per year riskier than the benchmarks.

Given that multifactor funds underperformed the benchmarks in terms of return, and they did so by exposing investors to a slightly higher volatility, they also underperformed the benchmarks in terms of risk-adjusted performance (RAP). In fact, they did so by a substantial 2.5% per year on a risk-adjusted basis, with RAPs of 10.5% for multifactor funds and 13.0% for the benchmarks. In addition, these funds did not provide investors with better downside protection; their average maximum drawdown (MD) was 26.4%, compared to an average drawdown for the benchmarks of 22.3%, for an underperformance of just over 4%.

Three questions were addressed simply by calculating correlation coefficients across all the funds in the sample. First, did older funds perform better? Second, did larger funds perform better? And third, did more costly funds perform better?Footnote 14 Only the first of these three questions has a positive answer. Although none of the correlations calculated are very large, and most of them are not statistically significant, the correlation coefficient between the number of observations and net return (0.30) and that between the number of observations and net risk-adjusted performance (0.28) both are significantly different from 0.Footnote 15

Finally, it is important to note that this inquiry focused on stocks funds and the most popular factors embedded in currently available financial products. For this reason, the results discussed are not necessarily relevant for strategies that combine asset classes, such as Bridgewater’s All Weather strategy (which holds similar risk exposures to assets that do well when, relative to expectations, growth or inflation rise or fall) or Fidelity’s Risk Parity Fund (which balances risk across four risk factors, namely, growth, inflation, real rates, and liquidity).Footnote 16

The assessment

Diversifying across companies, sectors, and countries has a very long history; diversifying across risk factors has been proposed more recently; and using multifactor funds that enable risk factor diversification by investing a single product is an even more recent development. For all the right (and perhaps obvious) reasons, investors have clearly and increasingly embraced market-wide, cap-weighted, low-cost diversification through index funds and ETFs. Such broad acceptance has raised the bar for products that offer a different type of diversification, more costly and typically based on weights independent from price. Although their short history precludes a definitive assessment, the evidence currently available suggests that multifactor funds have been largely a disappointment.

Multifactor funds that target the US market have largely underperformed market-wide, cap-weighted benchmarks in terms return and risk-adjusted return. Underperforming funds vastly outnumbered outperforming funds regardless of whether the S&P 500 or the Russell 3000 is used as a benchmark, and the same is the case if these indexes are replaced by investable ETFs that track them. In addition, in all these cases, there is an asymmetry in relative performance, with the margin of outperformance being far lower than that of underperformance. In other words, most multifactor funds underperformed the benchmarks and did so by a large margin, and the few that outperformed did so by a much smaller margin.

Multifactor funds that target the US market did not protect investors from severe downturns, either; in fact, their maximum drawdowns were far larger than those of the four benchmarks (two indexes and two ETFs) considered here. Furthermore, as was the case with return and risk-adjusted return, in terms of drawdowns the few funds than outperformed did so by a very small margin, and the many more that underperformed did so by a much larger margin.

Multifactor funds from global, international, and emerging markets, while still largely a disappointment, were somewhat more successful. Relative to US multifactor funds, the number of funds that outperformed in terms of return and risk-adjusted return was larger, and the difference between the margin of outperformance and underperformance was smaller. In terms of downside protection, there were still more underperforming funds than outperforming funds, but in this case the margin of outperformance was slightly higher than that of underperformance.

Regardless of the seemingly plausible idea underlying multifactor funds, and with the usual reservations that come with a limited track record, the prevailing evidence suggests a bearish assessment of these rather novel products. Both individual and institutional investors are likely to be better off, perhaps far better off, by diversifying the equity slice of their portfolios using widely available, market-wide, cap-weighted, low-cost index funds and ETFs.

Notes

A reviewer rightly points out that this is but one way of defining a factor; it is in fact admittedly general and other definitions are possible. Furthermore, as the reviewer suggests, it is indeed the case that there is no widely accepted methodology to estimate a return spread, although there does seem to be more agreement about estimating such spread over a ‘long’ investment horizon.

The outperformance of companies with low price relative to fundamentals over those with high price relative to fundamentals is referred to as both the style factor or the value factor.

That said, Arnott (2022) shows that the correlations across factors over the 2019-2021 period were relatively high (in excess of 0.70), with most of them in a relatively narrow (0.85–0.95) range.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for highlighting the need to clarify this distinction.

Estrada (2020) shows that making a portfolio more aggressive by introducing value and small-cap tilts yields a higher risk-adjusted performance than making the portfolio more aggressive by increasing the proportion of stocks in a two-asset portfolio of broadly diversified stocks and bonds.

An example of a fund providing indirect access to the style and size factors, but not marketed as a multifactor fund, is Invesco S&P 500 Equal Weight ETF (RSP). As the name of the fund suggests, it simply assigns equal weight to the components of the S&P 500, rebalancing quarterly. A three-factor regression for the period between this fund’s inception and Mar/2022 shows positive and (clearly) statistically significant exposures to both the style and the size factors.

Note that the mean return figures shown in the exhibit are geometric (or compound) mean monthly returns. However, the risk-adjusted return figures are obtained by dividing the arithmetic mean monthly return (not reported in the exhibit) by monthly volatility.

Modigliani and Modigliani (1997) argue that the RAP metric can be thought of as a way of ‘punishing’ (‘rewarding’) funds that are more (less) volatile than the benchmark by reducing (increasing) their observed return; the resulting figure is a return that accounts for the risk borne by the investor, expressed in percent. In addition, they emphasize that ranking funds with the RAP metric and with the Sharpe ratio leads to identical results.

As the last two rows of the right half of the exhibit show, the five funds that outperformed delivered a risk-adjusted performance of 17.2%, 0.7% higher than that of the Russell 3000 (16.5%); and 17.1%, 0.8% higher than IWV (16.3%). Those that underperformed, on the other hand, delivered a risk-adjusted performance of 12.5%, 4.3% lower than the Russell 3000 (16.8%); and 12.4%, 4.2% lower than IWV (16.6%).

In fact, over the Mar/2015-Mar/2022 period, the longest available for a US multifactor fund in the sample, the Morningstar Large Growth index returned 15.2% annualized (with 16.8% volatility), handsomely beating the 7.7% annualized return of the Morningstar Small Value index (with 21.6% volatility).

In this case, the exhibit shows that 10 funds outperformed the benchmarks and did so, on average, by 2.7% (–22.2% versus –24.9%); and 14 funds underperformed the benchmarks, and did so, on average, by 2.3% (–28.5% versus –26.2%).

Note that there are four lines in the table, two for US indexes as benchmarks and two for US ETFs as benchmarks. The rest of the (global, international, and emerging markets) funds are paired with their respective indexes to calculate the averages in the first two lines, and with their respective ETFs to calculate the averages in the next two lines.

For the first question, the age of a fund is measured with the number of observations of the fund in the sample. For the second question, the size of a fund is measured with the net assets of the fund at the end of March, 2022. And for the third question, the cost of a fund is measured with the expense ratio of the fund at the end of March, 2022.

These figures are based on the S&P 500 as the benchmark for the US market; for the Russell 3000 both correlations are slightly lower but still statistically significant. Net return (risk-adjusted performance) is defined as the return (risk-adjusted performance) of a fund minus that of the benchmark.

On this issue see the recent article by Kelliher et al. (2022), which discusses an approach to constructing a multi-asset portfolio balancing its risk exposure to growth, inflation, real rates, and liquidity.

References

Alquist, R., R. Israel, and T. Moskowitz. 2018. Fact, Fiction, and the Size Effect. Journal of Portfolio Management 45(1): 34–61.

Arnott, A. 2022. Does It Pay to Diversify by Factor? Morningstar, April 4, 2022. (Available at https://www.morningstar.com/articles/1087381/does-it-pay-to-diversify-by-factor.)

Arnott, R. 2014. What ‘Smart Beta’ Means to Us. Research Affiliates Fundamentals (August): 1–5.

Arnott, R., J. Hsu, and P. Moore. 2005. Fundamental Indexation. Financial Analysts Journal 61(2): 83–99.

Asness, C. 2016. The Siren Song of Factor Timing aka ‘Smart Beta Timing’ aka ‘Style Timing’. Journal of Portfolio Management 42(5): 1–6.

Asness, C., A. Frazzini, R. Israel, and T. Moskowitz. 2015. Fact, Fiction, and Value Investing. Journal of Portfolio Management 42(1): 34–52.

Banz, R. 1981. The Relationship Between Return and Market Value of Common Stocks. Journal of Financial Economics 9(1): 3–18.

Basu, S. 1977. The Investment Performance of Common Stocks in Relation to Their Price-Earnings Ratios: A Test of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. Journal of Finance 32(3): 663–682.

Blitz, D., and P. van Vliet. 2007. The Volatility Effect. Journal of Portfolio Management 34(1): 102–113.

Carhart, M. 1997. On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance. Journal of Finance 52(1): 57–82.

Clarke, R., H. de Silva, and S. Thorley. 2006. Minimum-Variance Portfolios in the U.S. Equity Market. Journal of Portfolio Management 33(1): 10–24.

Cochrane, J. 2011. Presidential Address: Discount Rates. Journal of Finance 66(4): 1047–1108.

Estrada, J. 2008. Fundamental Indexation and International Diversification. Journal of Portfolio Management 34(3): 93–109.

Estrada, J. 2020. Factor Tilts and Asset Allocation. Journal of Investment Consulting 20(1): 30–39.

Fama, E., and K. French. 1993. Common Risk Factors in the Returns of Stocks and Bonds. Journal of Financial Economics 33(1): 3–56.

Fama, E., and K. French. 2015. A Five-Factor Asset Pricing Model. Journal of Financial Economics 116(1): 1–22.

Haugen, R., and J. Heins. 1972. On the Evidence Supporting the Existence of Risk Premiums in the Capital Markets. Wisconsin Working Paper 4-75-20 (December).

Haugen, R., and J. Heins. 1975. Risk and the Rate of Return on Financial Assets: Some Old Wine in New Bottles. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 10(5): 775–784.

Hsu, J., and C. Campollo. 2006. New Frontiers in Index Investing. An Examination of Fundamental Indexation. Journal of Indexes (Jan/Feb): 32-58.

Idzorek, T., and M. Kowara. 2013. Factor-Based Asset Allocation vs. Asset-Class-Based Asset Allocation. Financial Analysts Journal 69(3): 19–29.

Jegadeesh, N., and S. Titman. 1993. Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency. Journal of Finance 48(1): 65–91.

Johnson, B. 2020. The Morningstar Factor Profile: A New Way to Better Understand Funds. Morningstar. October 8, 2020. (Available at https://www.morningstar.com/articles/1003817/the-morningstar-factor-profile-a-new-way-to-better-understand-funds).

Kelliher, C., A. Hazrachoudhury, and B. Irving. 2022. A Novel Approach to Risk Parity: Diversification across Risk Factors and Market Regimes. Journal of Portfolio Management 48(4): 73–90.

Lintner, J. 1965. The Valuation of Risk Assets and the Selection of Risky Investments in Stock Portfolios and Capital Budgets. Review of Economics and Statistics 47(1): 13–37.

Modigliani, F., and L. Modigliani. 1997. Risk-Adjusted Performance. Journal of Portfolio Management 23(2): 45–54.

Mossin, J. 1966. Equilibrium in a Capital Asset Market. Econometrica 34(4): 768–783.

Novy-Marx, R. 2013. The Other Side of Value: Good Growth and the Gross Profitability Premium. Journal of Financial Economics 108(1): 1–28.

Page, S., and M. Taborsky. 2011. The Myth of Diversification: Risk Factors versus Asset Classes. Journal of Portfolio Management 37(4): 1–2.

Ross, S. 1976. The Arbitrage Theory of Capital Asset Pricing. Journal of Economic Theory 13(3): 341–360.

Sharpe, W. 1964. Capital Asset Prices: A Theory of Market Equilibrium under Conditions of Risk. Journal of Finance 19(3): 425–442.

Titman, S., J. Wei, and F. Xie. 2004. Capital investments and stock returns. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 39(4): 677–700.

Treynor, J. 1962. Toward a Theory of Market Value of Risky Assets. Unpublished manuscript.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Mark Kritzman, Jack Rader, Larry Swedroe, and Arthur Thompson for their comments. Ignacio Talento provided valuable research assistance. The views expressed below and any errors that may remain are entirely my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Exhibit A1: multifactor funds

This exhibit shows the multifactor funds in the sample ordered alphabetically by their name, as well as their ticker, net assets (NA, in millions) and expense ratio (ER, in %) on Mar/31/2022, and inception date.

Fund | Ticker | NA | ER | Inception |

|---|---|---|---|---|

BlackRock U.S. Equity Factor Rotation ETF | DYNF | 90.0 | 0.30 | 3/19/2019 |

Fidelity Emerging Markets Multifactor ETF | FDEM | 24.5 | 0.45 | 2/26/2019 |

Fidelity International Multifactor ETF | FDEV | 16.4 | 0.39 | 2/26/2019 |

Fidelity Small-Mid Multifactor ETF | FSMD | 71.9 | 0.29 | 2/26/2019 |

First Trust Lunt U.S. Factor Rotation ETF | FCTR | 526.9 | 0.65 | 7/25/2018 |

FlexShares US Quality Large Cap Index Fund | QLC | 149.7 | 0.32 | 9/23/2015 |

Franklin LibertyQ Emerging Markets ETF | FLQE | 17.0 | 0.45 | 6/1/2016 |

Franklin LibertyQ Global Equity ETF | FLQG | 16.0 | 0.35 | 6/1/2016 |

Franklin LibertyQ International Equity Hedged ETF | FLQH | 17.2 | 0.40 | 6/1/2016 |

Franklin LibertyQ U.S. Equity ETF | FLQL | 966.7 | 0.15 | 4/26/2017 |

Franklin LibertyQ U.S. Mid Cap Equity ETF | FLQM | 62.9 | 0.30 | 4/26/2017 |

Franklin LibertyQ U.S. Small Cap Equity ETF | FLQS | 16.3 | 0.35 | 4/26/2017 |

Global X Adaptive U.S. Factor ETF | AUSF | 178.9 | 0.27 | 8/24/2018 |

Goldman Sachs ActiveBeta Emerging Markets Equity ETF | GEM | 1227.5 | 0.45 | 9/25/2015 |

Goldman Sachs ActiveBeta International Equity ETF | GSIE | 3190.2 | 0.25 | 11/6/2015 |

Goldman Sachs ActiveBeta U.S. Large Cap Equity ETF | GSLC | 13,662.0 | 0.09 | 9/17/2015 |

Goldman Sachs ActiveBeta U.S. Small Cap Equity ETF | GSSC | 461.5 | 0.20 | 6/28/2017 |

Hartford Multifactor Developed Markets (ex-US) ETF | RODM | 1716.4 | 0.29 | 2/25/2015 |

Hartford Multifactor Emerging Markets ETF | ROAM | 42.3 | 0.44 | 2/25/2015 |

Hartford Multifactor Small Cap ETF | ROSC | 28.8 | 0.34 | 3/23/2015 |

Hartford Multifactor U.S. Equity ETF | ROUS | 325.1 | 0.19 | 2/25/2015 |

Invesco Russell 1000 Dynamic Multifactor ETF | OMFL | 1849.2 | 0.29 | 11/8/2017 |

Invesco Russell 2000 Dynamic Multifactor ETF | OMFS | 168.4 | 0.39 | 11/8/2017 |

iShares MSCI Emerging Markets Multifactor ETF | EMGF | 891.6 | 0.45 | 12/8/2015 |

iShares MSCI Global Multifactor ETF | ACWF | 132.9 | 0.35 | 4/28/2015 |

iShares MSCI Intl Multifactor ETF | INTF | 896.2 | 0.15 | 4/28/2015 |

iShares MSCI Intl Small-Cap Multifactor ETF | ISCF | 199.1 | 0.40 | 4/28/2015 |

iShares MSCI USA Multifactor ETF | LRGF | 1237.9 | 0.08 | 4/28/2015 |

iShares MSCI USA Small-Cap Multifactor ETF | SMLF | 1031.9 | 0.30 | 4/28/2015 |

John Hancock Multifactor Developed International ETF | JHMD | 514.0 | 0.39 | 12/15/2016 |

John Hancock Multifactor Emerging Markets ETF | JHEM | 697.2 | 0.49 | 9/27/2018 |

John Hancock Multifactor Large Cap ETF | JHML | 849.0 | 0.29 | 9/28/2015 |

John Hancock Multifactor Mid Cap ETF | JHMM | 2566.5 | 0.41 | 9/28/2015 |

John Hancock Multifactor Small Cap ETF | JHSC | 413.4 | 0.42 | 11/8/2017 |

JPMorgan Diversified Return Emerging Markets Equity ETF | JPEM | 173.0 | 0.44 | 1/7/2015 |

JPMorgan Diversified Return International Equity ETF | JPIN | 814.4 | 0.37 | 11/5/2014 |

JPMorgan Diversified Return U.S. Equity ETF | JPUS | 605.6 | 0.18 | 9/29/2015 |

JPMorgan Diversified Return U.S. Mid Cap Equity ETF | JPME | 242.9 | 0.24 | 5/11/2016 |

JPMorgan Diversified Return U.S. Small Cap Equity ETF | JPSE | 205.9 | 0.29 | 11/15/2016 |

Legg Mason Small-Cap Quality Value ETF | SQLV | 19.3 | 0.61 | 7/12/2017 |

O’Shares U.S. Quality Dividend ETF | OUSA | 827.0 | 0.48 | 7/14/2015 |

O’Shares U.S. Small Cap Quality Dividend ETF | OUSM | 161.8 | 0.48 | 12/30/2016 |

PGIM Quant Solutions Strategic Alpha International Equity ETF | PQIN | 37.2 | 0.29 | 12/4/2018 |

Principal U.S. Small-Cap Multi-Factor ETF | PSC | 771.1 | 0.38 | 9/21/2016 |

RAFI Dynamic Multi-Factor Emerging Markets Equity ETF | MFEM | 82.7 | 0.51 | 8/31/2017 |

RAFI Dynamic Multi-Factor International Equity ETF | MFDX | 91.2 | 0.39 | 8/31/2017 |

RAFI Dynamic Multi-Factor U.S. Equity ETF | MFUS | 91.5 | 0.29 | 8/31/2017 |

SPDR MSCI EAFE StrategicFactors ETF | QEFA | 855.5 | 0.30 | 6/4/2014 |

SPDR MSCI Emerging Markets StrategicFactors ETF | QEMM | 74.5 | 0.30 | 6/4/2014 |

SPDR MSCI USA StrategicFactors ETF | QUS | 952.7 | 0.15 | 4/15/2015 |

Vanguard U.S. Multifactor ETF | VFMF | 154.8 | 0.18 | 2/13/2018 |

VictoryShares US Multi-Factor Minimum Volatility ETF | VSMV | 160.0 | 0.35 | 6/22/2017 |

WisdomTree International Multifactor Fund | DWMF | 32.9 | 0.38 | 8/10/2018 |

WisdomTree U.S. Multifactor Fund | USMF | 223.9 | 0.28 | 6/29/2017 |

Xtrackers FTSE Developed ex-US Multifactor ETF | DEEF | 78.0 | 0.24 | 11/23/2015 |

Xtrackers Russell US Multifactor ETF | DEUS | 164.2 | 0.17 | 11/23/2015 |

Exhibit A2: Benchmarks

This exhibit shows, for all the regions considered, the name of all the indexes and ETFs used as benchmarks, the abbreviation used for the former and ticker of the latter, and expense ratio of all ETFs on Mar/2022.

Panel A: Indexes Used as Benchmarks | ||

|---|---|---|

Region | Index | Abbreviation |

USA | Standard & Poor’s 500 | S&P 500 |

USA | Russell 3000 | R3000 |

Global | MSCI All Country World Index | ACWI |

International | MSCI All Country World Index excluding USA | ACWI ex-US |

Emerging | MSCI Emerging Markets Index | EMI |

Panel B: ETFs Used as Benchmarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Region | ETF | Ticker | Expense ratio (%) |

USA | iShares Core S&P 500 ETF | IVV | 0.03 |

USA | iShares Russell 3000 ETF | IWV | 0.20 |

Global | iShares MSCI ACWI ETF | ACWI | 0.32 |

International | iShares MSCI ACWI ex-US ETF | ACWX | 0.32 |

Emerging | iShares Core MSCI Emerging Markets ETF | IEMG | 0.09 |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Estrada, J. Multifactor funds: an early (bearish) assessment. J Asset Manag 24, 299–311 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-023-00314-3

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-023-00314-3