Abstract

Background

Multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD) is characterized by a systemic lymphoproliferative disorder affecting systemic lymph nodes. Cerebrovascular involvements have rarely been reported, and to our knowledge, cerebral angiitis causing subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in patients with Multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD) has not been previously described.

Case presentation

We identified two cases of MCD with SAH who were receiving immunosuppressive therapy with low dose prednisolone. Both patients presented with sudden-onset headache and were diagnosed with cortical SAH in the sulci by a computed tomography scan. Digital subtraction angiography showed segmental stenosis in the peripheral area of the middle cerebral artery. In both cases, cerebral angiitis causing SAH induced by a systemic inflammatory condition and elevated levels of interleukin (IL) -6 were suspected and resolved over a period of several months.

Conclusion

Our cases highlight the clinical diversity of the potential causes of cerebral angiitis and expand the association of MCD and cortical SAH; however, cortical SAH patients have a more favorable outcome than aneurysmal SAH patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Castleman’s disease (CD) was initially described by Benjamin Castleman et al. in 1956 as a disease with solitary hyperplastic mediastinal lymph nodes containing small, hyalinized follicles and a marked interfollicular vascular proliferation [1]. CD is caused by infection of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Such viral infections cause B cells in the lymph nodes to excessively release interleukin (IL) -6 or similar polypeptides and cause several autoimmune clinical symptoms [2]. CD is classified into two subgroups, unicentric Castleman’s disease (UCD) and multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD). UCD usually affects one lymph node area and the patients are often asymptomatic. In contrast, MCD affects systemic lymph nodes and the patients present various symptoms, such as hyperthermia, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, pulmonary disorders, edema, and ascites. MCD also may be associated with a variety of malignant diseases, such as Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, POEMS syndrome: polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endoclinopathy, monoclonal proteinemia and skin changes [2]. About the vascular involvements of MCD, temporal arteritis [3] and some cases of coronary and lower limb vascular involvements have been described. In general, it is unusual that the patients of MCD will present neurological symptoms, and intracranial involvements of the MCD have been rarely reported in the literature to date [4]. An association of MCD with some types of intracranial tumors, such as chordoid meningioma and clear cell meningioma, has been reported in some cases [5]. The pathogenesis of MCD in cases with such intracranial tumors remains unclear, but a complex cytokine network, including IL-6, IL-1β and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), may contribute to the growth of the tumor [6]. Although there are some reports of cerebrovascular involvements in patients with MCD, all of the presented cases had ischemic stroke caused by cerebral angiitis secondary to a systemic inflammatory condition, as indicated by excessive serum levels of IL-6 [7, 8]. To our knowledge, no reports are currently available about cerebral angiitis causing subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in patients with MCD. Here, we describe two rare cases of MCD associated with cerebral angiitis leading to SAH.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 57-year-old woman was admitted to a nearby hospital because of respiratory discomfort due to exercise, where a laboratory examination showed high levels of serum gamma globulin. She was then referred to our hospital for further examination. On admission, her physical examination showed a swelling of the lymph nodes of the mediastinum and axillary fossa. Laboratory examination showed anemia (hemoglobin: 3.9 g/dl), hypoalubuminemia (1.5 g/dl), hypergammaglobulinemia (IgG: 8140 mg/dl, normal: 870–1700 mg/dl, IgA: 851 mg/dl, normal: 110–410 mg/dl, IgM: 297 mg/dl, normal: 46–260 mg/dl) and an elevation of serum levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) (9.8 mg/dl). The serum IL-6 level was 43.5 pg/ml (normal < 4.0 pg/ml). An HIV viral examination was negative. HHV-8 examination was undone. A chest X-ray showed a reticular shadow of bilateral lung fields. Histopathological examination by transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) to lung lesions showed plasmacystic proliferation. The histopathological findings led to her to be diagnosed as MCD, and we started to administrate prednisolone orally (50 mg/day). Thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy (including anticoagulant-induced) was not identified based on the laboratory findings, and any other infection or autoimmune disorder was excluded. Three months after admission to our hospital, she suddenly felt a strong headache. She was alert and presented no apparent neurological deficit. The level of immunoglobulins and other laboratory findings were similar to those recorded previously. Her blood pressure was 148/88 mmHg, and her other vital signs were within normal range. A head computed tomography (CT) scan showed cortical SAH along the left frontal sulci (Fig. 1a). Further evaluation by fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the distribution of SAH and a hyperintense signal in the cortical-subcortical regions of the right parietal lobe (Fig. 1b). The corresponding diffusion-weighted images (not shown) were normal. We performed digital subtraction angiography (DSA) emergently to search for the source of bleeding. We could not find vascular abnormalities, but we did find segmental stenosis and delayed flow of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) (Fig. 1c). We diagnosed that the stenosis due to angiitis caused both SAH and ischemic change, and we performed antihypertensive therapy by infusion of a calcium-channel blocker. The follow-up DSA obtained after ten days from onset showed newly segmental stenosis of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and progression of the stenosis of the MCA (Fig. 1d). Angiography of the bilateral renal artery in the same examination also showed stenosis of the peripheral renal artery (not shown). These results indicated that systemic angiitis associated with MCD might have occurred, and we continued prednisolone therapy (decreased to 22.5 mg/day). Fortunately, she did not present neurological focal deficit including high function disorder, and her headache became weakened day by day. SAH completely disappeared and no de novo stenosis of intracranial artery in the other portion by 1 month, as determined by MRI, and no other event was recognized during an 8-year follow-up period.

Neuroimaging findings of Case 1. a CT scan of the head shows a cortical subarachnoid hemorrhage along the left frontal sulci (arrow heads). b FLAIR sequence of the MRI shows the distribution of a subarachnoid hemorrhage (arrow heads) and hyperintense signal in the cortical-subcortical regions of the right parietal lobe (arrow). c Lateral view of the left internal carotid angiogram shows stenosis in the area of the peripheral middle cerebral artery. d Lateral view of the left internal carotid angiogram obtained ten days after onset shows diffuse segmental stenosis in the area of both the anterior and middle cerebral artery

Case 2

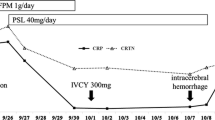

A 59-year-old woman found a rash on her abdomen 20 years ago. At 51 years of age, she was diagnosed with anemia and hypergammaglobulinemia at an annual health checkup. For further examination, she was admitted to a general hospital near her home. There, a physical examination did not find swelling of lymph nodes or any other abnormal findings. A laboratory examination found anemia (hemoglobin: 9.1 g/dl), hypoalubuminemia (2.1 g/dl), hypergammaglobulinemia (IgG: 6627 mg/dl, IgA: 798 mg/dl, IgM: 765 mg/dl) and an elevation of serum levels of CRP (9.8 mg/dl) and the serum IL-6 level (131 pg/ml). HIV viral examination was negative. HHV-8 examination was undone. Past examinations showed that she had neither thrombocytopenia nor coagulopathy. A chest and abdominal CT scan showed an interstitial shadow at the bilateral lung fields and mild splenomegaly. Biopsy of the lesion showed the proliferation of plasmacyte around vessels within true skin. She was diagnosed with MCD at 57 years old and started oral prednisolone (20 mg/day). At 58 years of age, she was introduced to our hospital because she moved to a home and continued prednisolone therapy. The condition of the disease was relatively stable, but the long-term administration of prednisolone was expected to risk systematic complications. We started to infuse tocilizumab, a humanized anti-human IL-6 receptor antibody, and decreased the dose of prednisolone to 12.5 mg/day. One day, she was admitted to the emergency room of our hospital complaining of sudden-on-set headache, and she was alert and presented no apparent neurological deficit. Her blood pressure was relatively high (180/90 mmHg), and other laboratory findings, including the level of immunoglobulin E, were almost within normal ranges. Head CT showed subtle cortical SAH along the right parietal sulci (Fig. 2a). FLAIR images showed the distribution of cortical SAH in right parietal sulci (Fig. 2b). The emergent right internal cerebral angiography, late arterial phase, showed stenosis and post-stenotic delayed opacification in the area of the peripheral middle cerebral artery; this perfusion area corresponded to the location of SAH (Fig. 2c). The follow-up DSA after one week after onset showed the disappearance of both stenosis and disturbed perfusion (Fig. 2d), and her headache got better and also the focal deficit was not presented. After 1-year from the discharge, cortical SAH was completely disappeared and no other vascular lesion was detected by the follow-up MRI, and no other event was recognized in the follow-up period.

Neuroimaging findings of Case 2. a CT scan of the head shows a subtle cortical subarachnoid hemorrhage along the right parietal sulci (arrow heads). b FLAIR sequence of the MRI shows the distribution of a subarachnoid hemorrhage (arrow heads). c Lateral magnified view of the right internal carotid angiogram, late arterial phase, shows a stenosis (arrow) and post-stenotic delayed opacification in the area of peripheral middle cerebral artery. d Lateral magnified view of the right internal carotid angiogram obtained one week after onset shows a disappearance of stenotic findings and normal perfusion (arrow)

Discussion

Only in some cases in MCD, the cerebrovascular involvements of ischemic stroke due to cerebral angiitis have been reported, especially in the cases of MCD with POEMS syndrome [7, 8]. Rössler M et al. reported on a case of young female with POEMS syndrome presented recurrent ischemic stroke due to cerebral vasculitis. In this case, DSA showed the segmental stenosis of proximal ACA [9]. Garcia T et al. described two cases of POEMS syndrome and MCD accompanied with recurrent ischemic stroke, in which DSA showed diffuse non-atherosclerotic segmental stenosis of the intracranial arteries. They hypothesized that the stenosis might be induced by the overproduction of cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-1β and VEGF in MCD, however they concluded the pathogenesis remained unclear [10]. Among these inflammatory biomarkers, IL-6 is well known to play an important role in acute inflammatory response triggered by cerebral ischemia, and an elevated blood IL-6 concentration is associated with poor outcome after stroke [11]. Moreover, a higher level of serum IL-6 is also associated with an increased risk of recurrent vascular events after stroke [9]. Despite these conclusive findings in both acute and chronic phases that clearly indicate an important role of IL-6 in stroke patients, these associations are not fully understood. According to these reports, elevated levels of IL-6 might be a major causal factor in the occurrence of cerebral angiitis in our patients with MCD and a lasting chronic over-expression of IL-6. Further research is required to substantiate the role of these biomarkers and to determine whether any of them may serve as a prognostic factor or therapeutic target to prevent cerebral angiitis in MCD.

On the other hand, there is no report of hemorrhagic stroke due to cerebral angiitis in patients with MCD. In our two cases of MCD accompanied with SAH, it is pathognomonic that both cases presented with cortical SAH isolated along sulci, and both cases are accompanied with the segmental stenosis of peripheral intracranial arteries. The stenosis in these cases may be due to angiitis and SAH induced by the vulnerability of the arterial wall. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the angiographic findings of angiitis appeared not only in intracranial arteries but also in bilateral renal arteries in case 1. As previously reported, the prognosis of patients with cortical SAH carried a favorable outcome than that of aneurysmal SAH [12]. Despite the presence of severe vasoconstriction, ischemic stroke, and cortical SAH, our case also experienced a favorable outcome, so a noninvasive imaging work-up, such as CT angiography or MR angiogram, should be introduced after an initial DSA does not identify any other underlying etiology.

Because there is no conclusive test that can be used to diagnosis cerebral angiitis, it is crucial to exclude the many other conditions that can mimic the symptoms of cerebral angiitis. First, patients with clinical and imaging features, such as severe headache, variable neurological deficits, and reversible arterial abnormalities (dilatations and stenosis), can be separately recognized as the reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS). Approximately one-third of patients with RCVS develop ischemic stroke, lobar hemorrhage, or convexal SAH. RCVS-related SAH likely results from dynamic caliber changes affecting cortical surface vessels, and it is also usually restricted to 1 to 2 sulcal spaces [13]. In our cases, reversible imaging findings were compatible with RCVS; however, we believe that the systemic inflammatory condition (i.e., MCD) possibly explained the reversible vasoconstriction. Second, the stenosis of intracranial arteries may be the ultra-early vasospasm that occurred immediately after SAH. Qurehi AI et al. reported in their study that 13 % of patients had evidence of ultra-early vasospasm (within the first 48 h), and the vasospasms were mild (vessel narrowing of 25–50 %) in 78 % of these patients [14]. Although immediate vasospasm of cortical SAH has been suspected, coexistence with these has never been reported in the literature. A possible explanation of this was that a small amount of extravascular blood of the cortical SAH has less local effect on cerebral arteries compared to aneurysmal one. Third, the long-term administration of glucocorticoid may also introduce the atherosclerotic stenosis of intracranial arteries. In such a case, the stenosis should not be segmental but widespread to all intracranial arteries, and we believe that it is difficult for the stenosis to recovery angiographically in such a short period. Moreover, the symptoms present relative slowly, not drastically. At present, we require additional careful considerations that distinguish RCVS or other possible causes from these systemic conditions until further studies can be performed.

Conclusions

We identified two cases of MCD who presented with sudden-onset headache and were diagnosed with cortical SAH. In both cases, cerebral angiitis causing SAH induced by a systemic inflammatory condition due to MCD. Our cases highlight the clinical diversity of the potential causes of cerebral angiitis and expand the association of MCD and cortical SAH.

Ethics and consent to participate

The authors declare that ethics approval was not required for this case report.

Consent for publication

In case 1, written informed consent for publication of this case report and any accompanying images was obtained from the patient’s family because she had passed away. In case 2, written informed consent was also obtained from the patient. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Abbreviations

- ACA:

-

anterior cerebral artery

- CD:

-

Castleman’s disease

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- DSA:

-

digital subtraction angiography

- FLAIR:

-

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- HHV-8:

-

human herpesvirus 8

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- IL-6:

-

interleukin-6

- MCA:

-

middle cerebral artery

- MCD:

-

multicentric Castleman’s disease

- POEMS:

-

polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endoclinopathy, monoclonal proteinemia and skin changes

- RCVS:

-

reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome

- SAH:

-

subarachnoid hemorrhage

- TBLB:

-

transbronchial lung biopsy

- UCD:

-

unicentric Castleman’s disease

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Castleman B, Iverson L, Menendez VP. Localized mediastinal lymphnode hyperplasia resembling thymoma. Cancer. 1956;9(4):822–30.

El-Osta HE, Kurzrock R. Castleman’s disease: from basic mechanisms to molecular therapeutics. Oncologist. 2011;16(4):497–511. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0212.

Lenner P, Lundgren E. Giant lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman’s disease) associated with temporal arteritis. Scand J Haematol. 1981;27(4):263–6.

Casper C. The aetiology and management of Castleman disease at 50 years: translating pathophysiology to patient care. Br J Haematol. 2005;129(1):3–17.

Kepes JJ, Chen WY, Connors MH, Vogel FS. “Chordoid” meningeal tumors in young individuals with peritumoral lymphoplasmacellular infiltrates causing systemic manifestations of the Castleman syndrome. A report of seven cases. Cancer. 1988;62(2):391–406.

Arima T, Natsume A, Hatano H, Nakahara N, Fujita M, Ishii D, et al. Intraventricular chordoid meningioma presenting with Castleman disease due to overproduction of interleukin-6. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(4):733–7.

Garcia T, Dafer R, Hocker S, Schneck M, Barton K, Biller J. Recurrent strokes in two patients with POEMS syndrome and Castleman’s disease. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;16(6):278–84.

Dupont SA, Dispenzieri A, Mauermann ML, Rabinstein AA, Brown Jr RD. Cerebral infarction in POEMS syndrome: incidence, risk factors, and imaging characteristics. Neurology. 2009;73(16):1308–12. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd136b.

Rössler M, Kiessling B, Klotz JM, Langohr HD. Recurrent cerebral ischemias due to cerebral vasculitis within the framework of incomplete POEMS syndrome with Castleman disease. Nervenarzt. 2004;75(8):790–4.

Bustamante A, Sobrino T, Giralt D, García-Berrocoso T, Llombart V, Ugarriza I, et al. Prognostic value of blood interleukin-6 in the prediction of functional outcome after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroimmunol. 2014;274(1–2):215–24. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.07.015.

Whiteley W, Jackson C, Lewis S, Lowe G, Rumley A, Sandercock P, et al. Association of circulating inflammatory markers with recurrent vascular events after stroke: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2011;42(1):10–6. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.588954.

Refai D, Botros JA, Strom RG, Derdeyn CP, Sharma A, Zipfel GJ. Spontaneous isolated convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage: presentation, radiological findings, differential diagnosis, and clinical course. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(6):1034–41. doi:10.3171/JNS.2008.109.12.1034.

Muehlschlegel S, Kursun O, Topcuoglu MA, Fok J, Singhal AB. Differentiating reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome with subarachnoid hemorrhage from other causes of subarachnoid hemorrhage. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(10):1254–60.

Qureshi AI, Sung GY, Suri MA, Straw RN, Guterman LR, Hopkins LN. Prognostic value and determinants of ultraearly angiographic vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(5):967–73.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for useful advice and suggestions from Dr. Hiroki Kawano, Dr. Yasuhiro Funada, and Dr. Yoshio Katayama. They also thank their patients and his families for participating in this study.

Funding

The authors declare that they obtained no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EK had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: AF, EK. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All of the authors. Drafting of the manuscript: JT. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All of the authors. Study supervision: AF, EK. All authors have read and approve of the final version of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, J., Fujita, A., Hosoda, K. et al. Cerebral angiitis associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage in Castleman’s disease: report of two cases. BMC Neurol 16, 60 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0585-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0585-4