Abstract

Purpose

Obesity and overweight are significant risk factors for many serious diseases. Several studies have investigated the relationship between emotional regulation and overweight or obesity in people with eating disorders. Although a few studies have explored alexithymia in individuals with severe obesity without eating disorders, no attention has been paid to individuals with overweight and preclinical form of obesity. This study aims to assess whether overweight and obesity are related to emotional dysregulation and alexithymia.

Methods

The study involved 111 undergraduate students who had not been diagnosed with an eating disorder. The sample was divided into two groups according to their body mass index (BMI): normal weight (N = 55) and overweight (N = 56). All of them completed the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20), the Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), and the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2).

Results

Results showed higher levels of alexithymia, and specifically higher difficulty in identifying feelings and an externally oriented thought, in participants with overweight. Multiple correlation analysis highlighted the positive relations between some EDI-2 subscales and both alexithymia and emotional regulation scores. Linear regressions revealed a significant relationship between body BMI and both alexithymia and emotional regulation strategies.

Conclusions

The condition of overweight/obesity seems to be associated with higher emotional dysregulation compared to normal weight condition. It is essential to study this relationship because it could represent a risk factor for the worsening of problems related to overeating and excessive body weight. These findings suggest that an integrated approach aimed at considering the promotion of emotional regulation could contribute to the effectiveness of a program designed to reduce overweight and obesity.

Level of evidence

Level III: case-control analytic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Overweight and obesity, identified as an excess of body fat, are significant risk factors for several chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, hypertension, and some forms of cancer [1]. Therefore, these conditions represent a significant public health problem [1]. Obesity is a heterogeneous syndrome with a multifactorial etiology, characterized by an imbalance between assimilated and consumed calories [2]. This condition is often determined by specific behavioral attitudes towards food, which are related to individual differences [3]. The classification of overweight and obesity is conventionally based on body mass index (BMI), an index given by the ratio between weight and height of an individual (kg/m2), which provides an indirect estimate of body fat through a definition of anthropometric height/weight characteristics [4]. The World Health Organization [1] has identified a broad diffusion of obesity; in 2014, 13% of the world adult population appeared to be obese (15% of women, 11% of men), with an exponential increase in child obesity [1].

The condition of obesity has been often associated with eating disorders [5], particularly with binge eating disorder (BED) [6, 7], or other medical conditions (e.g., metabolic syndrome), but it may also occur in the absence of eating or other medical diseases.

The higher diffusion of overweight and obesity has drawn attention to different psychological aspects that can affect eating behavior and cause a BMI increase. Many studies suggested that unhealthy eating habits, including overeating, could be the result of an attempt to regulate negative feelings [8,9,10]. A failure of emotional regulation could lead to a breakdown in the autoregulation of other personal areas, including those linked to the control of eating behavior [11, 12].

Emotional regulation is a multidimensional construct, defined as the ability to regulate one’s own emotions, both positive and negative, diminishing their contents, attenuating, maintaining, or amplifying them [13]. When considering emotional regulation, we refer to all cognitive and behavioral processes that influence the intensity, duration, and expression of emotions. Main theoretical models tried to define the aspects of emotional regulation. Thayer and Lane [14] have advanced the Neurovisceral Integration Model. According to this model, autonomic, attentional, and affective systems are considered parts of a network that modulates and affects emotional responses. Gratz and Roemer [15] proposed a six-component model that could justify psychopathological symptomatology. This model integrates all the aspects that could influence the emotional response, and it also considers the involved physiological (e.g., arousal modulation) and cognitive (e.g., understanding of emotions) dimensions of emotions.

One of the most studied models on emotional regulation has been proposed by Gross [16], who considered two specific mechanisms involved in the emotion regulation process: cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Cognitive reappraisal consists of cognitive change focused on modifying the potential emotional condition, and it is antecedent to emotional expression. Reappraisal is defined as the redefinition of a potentially emotion-eliciting situation in non-emotional terms. Expressive suppression, which consists of emotional response modulation, is focused on emotional response. Suppression allows inhibiting of ongoing emotion-expressive behavior [17].

Several studies have indicated that the most adaptive mechanism is reappraisal [e.g., 13, 17] since it reduces the emotional impact of the experience rather than suppress its expression, leaving the emotional effect on the individual unaltered. For these reasons, several studies have investigated the relationship between emotional dysregulation and some psychological and physical diseases [17,18,19,20]. Some studies highlighted that a condition of hyperarousal, linked to emotional dysregulation and emotional distress [18, 21], appears to be a risk factor for cardiovascular and heart diseases. Other studies have shown that emotional dysregulation characterizes anxiety and mood disorders [17, 19, 22].

A crucial construct related to emotional dysregulation is alexithymia. Alexithymia is a transdiagnostic dimension that indicates a functional alteration of the subjective awareness of affective processing [23]. It is characterized by difficulties in identifying and describing feelings and an externally oriented cognitive style [24]. Although the research did not agree on identifying alexithymia as a risk factor for the onset of psychological or physical pathologies [25,26,27], alexithymia has been closely associated with a worse prognosis of various health diseases and represents a construct to consider in the study of health-related risk factors [28]. Alexithymia has also been linked to unhealthy food habits, and it has been observed in people with eating disorders [29].

When emotions are dysregulated, maladaptive behaviors can be adopted that allows people to eat in response to feelings [11, 30]. This principle is at the basis of the Emotionally Driven Eating Model [10, 31]. This theoretical model allows explaining inappropriate eating behaviors because it considers dysfunctional emotional and cognitive processing as causes of overeating [10, 31]. Accordingly, a deficit in the regulation of eating behavior can be justified by a failure in emotional regulation that can lead to overeating behavior [11]. In summary, people with emotional dysregulation would use eating behavior, as well as diet, to compensate for an inability to employ proper cognitive strategies to process successful or avoid or inhibit a negative emotional state. This aspect is considered by different studies that tried to identify the role of emotional regulation in eating behavior [11, 32].

Some researchers, trying to identify the emotional pattern related to overeating, have observed a relationship between overweight or obesity conditions and emotional dysregulation [30, 33,34,35] in the presence of a binge eating disorder, showing higher levels of alexithymia and emotional dysregulation in individuals affected by both obesity and binge eating disorder than individual with obesity but without a binge eating disorder [36, 37]. A few studies analyzed the relationship between emotional dysregulation and obesity when a pathological eating disorder is not present [12, 38,39,40,41].

Although higher levels of emotional dysregulation and alexithymia appear to characterize more people affected by eating disorders than healthy populations [42, 43], their role in individuals with high BMI without an eating disorder is an aspect poorly investigated and verified. Some investigations have identified more significant levels of emotional dysregulation and alexithymia in people with severe obesity compared to participants with normal weight [41, 44,45,46]. High levels of alexithymia seem to be associated with a low reduction of body weight after bariatric surgery [47]. Moreover, a self-perception as “obese” after bariatric surgery is strongly associated with higher levels of alexithymia and worst psychological conditions [48].

In particular, higher levels of externally oriented thinking [41], and difficulty in identifying and describing feelings [45, 48] were found in people with severe obesity. However, other studies did not confirm this relationship [33, 49]. These inconsistent results could be due to the absence of normal weight groups characterized by high or low alexithymia levels when the studies were aimed to assess the differences between alexithymic and non-alexithymic individuals affected by severe obesity [33, 49]. Usually, researchers have investigated alexithymia in heterogeneous groups of participants: people with severe obesity [45, 49], often included in a waiting list for bariatric surgery [39, 50,51,52], or patients affected by both obesity and BED [30]. Other studies have analyzed the differences between individuals with obesity and with or without BED [34] or have carried out mood manipulations to investigate their effects on eating behavior, according to the emotionally driven eating model [10]. However, no study has analyzed whether alexithymia and emotional dysregulation, particularly in the dimensions of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, affect people with a preclinical form of obesity (BMI between 25 and 29.9) or obesity class I (BMI between 30 and 34.9).

In conclusions, the results of the studies are heterogeneous and did not clarify the relationship between emotional regulation and excessive body weight.

This study aims to understand the relationship between emotional regulation and overweight better. To find an emotional dysregulation in the preclinical stages of obesity could be useful in the prevention programs aimed at weight control. Although a cross-sectional design does not allow evaluating the causal direction between these variables, confirming this relationship could be helpful to implement interventions on eating habits and maladaptive emotional aspects. Moreover, to analyze the differences between participants with normal weight and individuals with excessive body weight could be useful to identify the emotional pattern related to body weight.

According to the findings revealing a relationship between emotional dysregulation and dysfunctional eating behavior [53,54,55], and to results of previous studies on the relationship between alexithymia and severe obesity in participant without eating disorders [41, 45], this study is aimed to verify the presence of higher emotional dysregulation and alexithymia in subjects with overweight (pre obesity and obesity class I) without an eating disorder diagnosis. The following hypotheses have been tested: (1) in agreement with the emotional eating model [17], and to the findings revealing an emotional difficulty in people with obesity [56], we expected to observe higher levels of both emotional dysregulation and alexithymia in young adults with overweight, not diagnosed with eating disorders, compared to people with normal weight. (2) We also expect to record more preclinical symptoms of eating disorders in the absence of an ED diagnosis in young adults with overweight and obesity, compared to people with normal weight. Moreover, we hypothesized that these symptoms should be positively correlated with alexithymia and emotional dysregulation [33, 49]. (3) According to the emotional eating model [12], BMI, considered as an index of overeating behavior, should be predicted positively by both alexithymia and expressive suppression and negatively by cognitive reappraisal.

Materials and methods

Participants

One-hundred and eleven Italian undergraduate students (mean age 24.49 ± 2.96 years; 66 females and 45 males), recruited from Sapienza University of Rome, took part voluntarily in the study. The exclusion criteria were: the clinical history and the current presence of eating disorders or other psychopathological disorders like depression or anxiety or medical conditions (such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, etc.), and a condition of underweight (BMI lower than 18.5). A clinical interview evaluated exclusion criteria.

Participants were divided into two groups: a group with normal weight (NW), with 55 participants (37 females and 18 males; mean BMI = 21.5; SD = 0.59), and a group with overweight (OW), including 56 participants (29 females and 27 males; mean BMI = 29.4; SD = 4.29). The OW group included 42 participants affected by overweight (21 females and 21 males; mean BMI = 27.6; SD = 0.91) and 14 participants affected by obesity (8 females and 6 males; mean BMI = 35.5; SD = 4.52) (Table 1).

Apparatus

Weight and height were assessed in the laboratory. The participant was asked to stand on an Laica professional digital balance, calibrated in kg, to measure the weight. The height of the participant was measured using a wall-mounted anthropometer. BMI was obtained by dividing weight (in kg) by height (in m2). The WHO [57] indicates the following range of values: underweight (BMI lower than 18.5); normal weight (BMI between 18.5 and 24.9); Preobesity (BMI between 25.0 and 29.9); obesity class I (BMI between 30.0 and 34.9); obesity class II (BMI between 35.0 and 39.9); and obesity class III (BMI equal or higher than 40).

Instruments

Twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) [24, 58] The TAS-20 is the most widely used and validated self-reported measure of alexithymia. It includes 20 items, which are rated using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The questionnaire represents the last version of the TAS [24] and shows a three-factor structure consisting of (1) difficulty identifying feelings (DIF; e.g., item 1: “I’m often confused about the emotions I feel”), (2) difficulty describing feelings (DDF; e.g., item 3: “I can easily describe my feelings”), and (3) externally oriented thinking (EOT; e.g., item 20: “Looking for hidden meanings in movies or comedies distracts from the pleasure of watching them”). Previous studies defined these three factors as congruent with the alexithymia construct and its main characteristics [24, 58]. People are considered as non-alexithymic if their global score is below or equal to 51. A score ranging between 52 and 60 defines possible alexithymia. Finally, people showing a score equal to or higher than 61 are considered alexithymic. The Italian version of this questionnaire reported a Cronbach reliability coefficient of 0.75 [58].

Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) [59, 60] The ERQ is a self-reported questionnaire including ten items, rated using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). The ERQ allows assessment of one’s own emotional control following one of two different strategies considered in the emotional regulation model of Gross [16]: cognitive reappraisal, a form of cognitive change that involves modifying the emotional impact of a situation, or expressive suppression, a form of response modulation characterized by the inhibition of the response driven by the emotion. An example of item investigating cognitive reappraisal is “To feel better (e.g., happy/content/raised/good-tempered), I try to look at situations from a different perspective”; an example of item investigating expressive suppression is “I keep my feelings for myself”. This questionnaire reported a Cronbach reliability coefficient of 0.84 for the Cognitive Reappraisal and 0.72 for Suppression Expressive [60].

Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2) [61, 62] The EDI-2 is a self-reported questionnaire including 91 items, which are rated using a six-point Likert scale (1 = never; 6 = always). It consists of eleven subscales for the clinical evaluation of cognitive and behavioral dimensions linked to eating disorders. The EDI-2 is considered as a multidimensional screening test because it does not give an eating disorder diagnosis but shows the relevant characteristics of eating disorders. The subscales bulimia (x items), body dissatisfaction, and drive for thinness are the main screening subscales used to determine levels of eating disorders. The other subscales are ineffectiveness, perfectionism, interpersonal distrust, interoceptive awareness, maturity fears, asceticism, impulse regulation, and social insecurity. These scales are used to evaluate the respondent’s approach to food and how it affects psychological and personal dimensions. The Italian version of EDI-2 showed higher reliability considering clinical populations (α between 0.78 and 0.84), while moderate reliability was found in the non-clinical population (α between 0.38 and 0.88) [62].

Procedure

The Ethics Committee of the Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology (“Sapienza” University of Rome) approved the research, which was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration. All participants were volunteers and have signed informed consent forms. After a brief clinical interview, participants filled out the EDI-2, and then the weight and height were measured. Finally, the TAS-20 and the ERQ were administered.

Data analysis

To define the sample’s size for this study, a power analysis, a priori, was conducted using G*Power [63]. The power analysis was applied considering a partial eta of 0.07 (over the medium effect of 0.06 indicated by Field [64]), an α of 0.05 and a Power (1 − β) of 0.80. The program generated an effect size of 0.27 (medium effect > 0.25) and an average sample size of 108 participants for this study (i.e., at least 54 participants per group).

A non-significance of Levine’s Tests for heterogeneity (p > 0.10) and a normal distribution of data confirmed the assumptions for the use of parametric analyses.

To assess the differences between groups, one-way univariate (ANOVA) considered the groups (normal weight; overweight/obesity) as the independent variable, and the psychological dimensions of emotional regulation of the Gross’ model (cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression), alexithymia (the global TAS-20 score and its facets), and the EDI-2 subscales as dependent variables were carried out.

To analyze the relationship between cognitive and behavioral components related to eating behavior and emotional regulation, a correlation analysis (Pearson’s r) was conducted between the EDI-2 subscales and ERQ and TAS-20 subscales. To reduce the risk of a Type 1 error, a Bonferroni’s correction indicated a p value of 0.008 as acceptable (p value of 0.05 divided by the multiple comparisons of EDI-2 subscales with ERQ and TAS-20 subscales).

Two different standard multiple linear regression analyses, which considered both BMI as the dependent variable, have evaluated whether TAS-20 and ERQ scores predicted BMI. For the first regression, the ERQ subscales, and the Total Score of TAS-20 were entered as independent variables to show if the interaction of Cognitive Reappraisal, Expressive Suppression, and Alexithymia predicted the BMI variations. For the second regression, the scores of the TAS-20 scales, and ERQ scales were inserted as independent variables, to show if the interaction between the two dimensions of emotional regulation, difficulty in identifying feelings, difficulty in describing feelings and externally oriented thinking predicted the change in the BMI.

Statistical analysis was conducted using STATISTICA v10.0.

Results

Table 1 shows the means (± SD) of the scores obtained by the two groups on the questionnaires.

Alexithymia

The results showed a significant difference in the global score of the TAS-20 (F1,110 = 9.16; p = 0.003; pη2 = 0.10), which revealed higher scores in participants with overweight than in participants with normal weight. The ANOVAs on the scores of the TAS-20 subscales highlighted that difficulty identifying feelings (F1,109 = 8.85; p = 0.004, pη2 = 0.10) and externally oriented thinking (F1,109 = 7.05; p = 0.009; pη2 = 0.10) were significantly different (Fig. 1). Participants with overweight show higher scores than normal weight participants in both the subscales. Difficulty describing feelings was not significantly different between groups (F1,109 = 0.83; p = 0.36).

Emotional regulation

The ANOVA on the ERQ subscales did not show significant differences in both cognitive reappraisal (F1,109 = 1.49; p = 0.22) and expressive suppression (F1,109 = 3.30; p = 0.07; pη2 = 0.03), even though a higher expressive suppression in the OW group than in the NW group was present (Fig. 2).

Eating disorder symptomatology

The results of the EDI-2 questionnaire did not show pathological scores in the two groups [41, 42]. The one-way ANOVAs that considered the scores of each subscale of the EDI-2 show significant differences between groups in the subscales bulimia (F1,108 = 6.02; p = 0.01; pƞ2 = 0.05), body dissatisfaction (F1,108 = 13.12; p = 0.0004; pƞ2 = 0.11), perfectionism (F1,108 = 4.24; p = 0.04; pƞ2 = 0.04), maturity fears (F1,108 = 6.66; p = 0.01; pƞ2 = 0.07), asceticism (F1,108 = 7.21; p = 0.008; pƞ2 = 0.06), and impulse regulation (F1,108 = 6.72; p = 0.01; pƞ2 < 0.06). Specifically, the group with overweight showed higher scores than NW in all these subscales (Table 1). No differences were found in the drive for thinness (F1,108 = 1.74; p = 0.19), interoceptive awareness (F1,108 = 2.43; p = 0.12), social insecurity (F1,108 = 0.67; p = 0.41), ineffectiveness (F1,108 = 3.92; p = 0.06; pƞ2 = 0.04) and interpersonal distrust (F1,108 = 3.57; p = 0.06; pƞ2 = 0.03) subscales.

Correlations

The linear correlation analyses among the scores of the EDI-2, the TAS 20 and the ERQ subscales are shown in the Table 2. There were significantly positive correlations between the scores of some EDI-2 subscales and the dimensions of emotional regulation measured by the ERQ and the TAS-20. In particular, positive correlations were found between expressive suppression and the EDI-2 subscales bulimia (p = 0.007), asceticism (p = 0.0001) interpersonal distrust (p = 0.0001), ineffectiveness (p = 0.001), interoceptive awareness (p = 0.03), impulse regulation (p = 0.02). However, considering Bonferroni’s correction, only asceticism and interpersonal distrust can be considered significant. Negative correlations were found between cognitive reappraisal and the EDI-2 subscales body dissatisfaction (p = 0.02), ineffectiveness (p = 0.0001), interpersonal distrust (p = 0.03), maturity fears (p = 0.06), but only ineffectiveness was significant after Bonferroni’s correction. The Total Score of the TAS-20 was positively correlated with bulimia (p = 0.002), ineffectiveness (p = 0.0001), perfectionism (p = 0.002), interpersonal distrust (p = 0.0001), interoceptive awareness (p = 0.0001), maturity fears (p = 0.01), asceticism (p = 0.0001), impulse regulation (p = 0.0001); however, after Bonferroni’s correction, bulimia (p = 0.002), perfectionism (p = 0.002), and, maturity fear were no longer significant. Difficulty in identifying feelings showed positive correlations with the EDI-2 subscales bulimia (p = 0.0001), body dissatisfaction (p = 0.005), ineffectiveness (p = 0.0001), perfectionism (p = 0.001), interpersonal distrust (p = 0.0001), interoceptive awareness (p = 0.0001), maturity fears (p = 0.0001), asceticism (p = 0.0001), impulse regulation (p = 0.0001), but, after Bonferroni’s correction, body dissatisfaction and perfectionism did not result significant. Difficulty in describing feelings showed positive correlations with EDI-2 subscales ineffectiveness (p = 0.002), perfectionism (p = 0.001), interoceptive awareness (p = 0.001) and asceticism (p = 0.01); none of these correlations remained significant after Bonferroni’s correction. Externally oriented thinking showed a positive correlation with EDI-2 subscale interpersonal distrust (p = 0.0001).

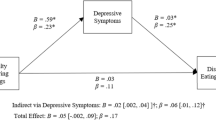

Regression models

The linear regression model that considered the total score of the TAS-20 and the scores in the two ERQ subscales as the independent variables, and BMI as the dependent variable, showed a significant effect (F3,106 = 5,10; p = 0.002; R2 = 0.12; Adjusted R2 = 0.10), but only the total score of the TAS-20 showed a significant beta effect (p = 0.05; Table 3).

The regression model that considered the score of TAS-20 subscales and ERQ subscales as the independent variables, and BMI as the dependent variable was significant (F5,104 = 3.54; p = 0.005; R2 = 0.15; Adjusted R2 = 0.10). Considering the single variables, only the externally oriented thinking showed a significant beta effect (p = 0.05; Table 4); while, the beta index of the expressive suppression (ERQ subscales) did not show effect (p = 0.07; Table 4).

Discussion

A high BMI reflects an increased risk of premature death and decreased quality of life [65]. For these reasons, analyzing the presence of risk factors or psychological characteristics associated with an increased BMI is an essential goal for the scientific community. The presence of higher levels of emotional dysregulation and alexithymia in people with eating disorders was confirmed by many studies [37, 66,67,68,69]. On the one hand, many patients with an eating disorder are categorized as alexithymic [70,71,72,73]. On the other hand, by considering alexithymia as a continue dimension, it has been shown that individuals with eating disorders presented higher alexithymia levels [53, 74, 75].

It is also well known that emotional dysregulation is often present in unhealthy eating behaviors [53, 54] and eating disorders, like anorexia [55, 76], bulimia [77] or BED [78]. Furthermore, the severity of an eating disorder is significantly related to the patient’s difficulty in emotional regulation [79]. To our knowledge, no studies have considered the presence of emotional dysregulation or alexithymia in preclinical form of obesity in the absence of an eating disorder diagnosis. Evaluating this relationship can be very suitable because emotional dysregulation is a transdiagnostic construct common to different psychopathologies. It could be useful to verify whether emotional dysregulation represents a risk factor for the loss of control of eating behavior, likewise emotionally driven eating in the binge eating disorder [80].

One of the aims of this study was to understand the relationship between some component of emotional regulation, as cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression of Gross’ model [16], alexithymia and overweight, trying to identify the differences between young adults with overweight and normal weight.

The findings of the current study suggest that overweight individuals show higher difficulty in the identification of their feelings compared to normal-weight people. Moreover, they seem to present a behavioral pattern aimed at focusing on life events in a concrete way, as expressed by the high scores in the externally oriented thinking [74]. The results concerning Difficulty in Identifying Feelings confirm the results of the studies on people with eating disorders [73, 76, 81]. Our findings also agree with the results revealed by individuals with severe obesity that showed a high difficulty identifying feeling [41, 46]. Nevertheless, our results contrast with those of other studies that did not observe a relationship between BMI and alexithymia [33, 46, 56]. It is interesting to note that although several studies have found a higher Difficulty in Describing Feelings in people with eating disorders [37, 73, 81, 82], we did not confirm this behavior in individuals with overweight. However, this result agrees with the conclusions of a recent systematic review that confirm higher levels of alexithymia and emotional dysregulation in individuals with obesity with or without BED, but no difficulty in describing feelings [56]. A possible explanation is that obesity could be characterized by a perception of being able to express emotions, even if these are not well identified [56]. Another interpretation refers to their ability to label their feelings, even when they are not precisely perceived [56].

The results concerning externally oriented thinking replicate the observations made in people with eating disorders [82] and severe obesity [41, 46]. Therefore, a common aspect of behavioral eating disorders and overweight/obesity could concern emotional regulation. In general, participants with overweight showed higher levels of alexithymia than normal-weight participants. It is interesting to note that this result was observed even though the prevalence of alexithymia was lower in the participants of the present study than in the general population [83]. We can conclude suggesting that alexithymic individuals, and specifically those characterized by a difficulty in identifying their emotional state, and an external-oriented thinking, tend to regulate their emotions through maladaptive overeating behaviors that allow to an increase in BMI.

Emotional regulation is fundamental for human adaptation and seems to be closely related to social functioning and subjective well-being [16]. It has been hypothesized [84] a correlation between alexithymia and both expressive suppression (positively) and cognitive reappraisal (negatively). Experimental studies confirm this relationship, showing higher expressive suppression in alexithymic than in non-alexithymic subjects [85]. In the present study, no significant differences between groups in cognitive reappraisal and suppressive expression have been observed, contrarily to the results of previous studies on people with problematic eating behaviors [9, 12, 79, 86], obesity [12], BED [9, 56], anorexia and bulimia [79, 86]. It could be interesting to note that the mean scores of expressive suppression were higher in the group with overweight than in the participants with normal weight. The differences between our findings and those of the other studies [9, 12, 79, 86] can be due to the preclinical characteristics of obesity and the absence of eating disorders in our sample. Further studies should analyze the role of cognitive and behavioral components of emotional regulation in the variation of BMI for supporting the view of emotional eating aimed at restoring the poor emotional control.

In conclusion, although there is a robust body of research that evidences specific deficits in identifying and describing feelings in clinical populations, this is the first study that analyzes emotional regulation and alexithymia in individuals with preclinical obesity. Nevertheless, the results of the present study were similar to those observed in people with severe obesity but without eating disorders [39, 45, 46].

The higher levels of alexithymia in individuals with overweight and without a clinical diagnosis of eating disorders confirm that eating habits are influenced by emotions [11, 38]. These results also seem to support the hypothesis suggesting that alterations in emotional regulation could contribute to unrestrained diet (binge eating) at the base of an increase in BMI [11], although further studies are necessary.

Another hypothesis of this study predicted higher preclinical symptoms of eating disorders in the participants with overweight. This prediction was confirmed. The results observed with the EDI-2, and specifically the correlations between preclinical symptoms of eating disorders and both emotional regulation and alexithymia, further prove previous findings [87] and also indicate a dysfunctional psychological profile in people with overweight. This problematical style could influence self-image and the approach to the external world [43]. According to previous results [33], our findings could provide interesting perspectives for analyzing the relationship between eating habits and emotional regulation, in the absence of eating disorders. In fact, the results show how emotional regulation is related to different cognitive and psychological aspects of the behavioral eating disorders profile, such that given by the EDI-2, in individuals with overweight.

Another aim of the study was to define the predictive role of alexithymia and emotional regulation strategies in the increase of BMI. The two linear regression models confirmed these relationships, but they are weak and explained only a low percentage of variance (about 15% of the BMI change in both linear regression models). However, the role of the single subscales was negligible (except for the externally oriented thinking). These results could suggest that only the interaction of multiple dimensions of emotional regulation, rather than a single aspect, could explain changes in BMI. This hypothesis agrees with recent results [40] that highlighted the role of the interaction among emotional dysregulation, anxiety, and depression in determining eating habits and emotional eating via negative affect or negative urgency.

The findings of this study further confirm the relationship between body mass index and many aspects of emotional regulation, but they did not allow us to establish a causal direction between the variables. For this aim, longitudinal studies are needed.

Conclusions

Although the scientific literature has investigated the relationship between emotional self-regulation and eating behavior [11], it is still unclear what emotional regulation strategies are adopted by individuals with inappropriate eating habits. This study adds a piece of knowledge on this topic, in particular, in people without a manifested eating disorder and who do not show severe obesity. The findings observed in the present study agree with those found in clinical populations with severe obesity or eating disorders and suggest that emotional regulation also affects eating behavior in the absence of these clinical conditions.

From our point of view, the results of this study could have two possible implications. On the one hand, emotional dysregulation could represent a risk factor associated with an increase in BMI [28] and a worse prognosis in overweight and obesity problems. Poor impulse control and attempts to self-regulate emotions through eating could worse incorrect food behaviors until severe obesity is reached, as highlighted by the studies on people with severe obesity and eating disorders [12, 29]. On the other hand, an excessive BMI, and all the social and personal implications it involves can produce an emotional dysregulation associated with attempts to self-regulation. This interpretation agrees with the results of studies that underlie the role of self-esteem in alexithymia and eating behavior [33]. To get to more robust conclusions, it is essential to investigate additional variables that could influence this relationship, such as mood, self-perception, and locus of control, which could play a role as moderator or mediator of this relationship [40, 48, 64].

The choice of the present study to focus on people without eating disorders could be functional in the perspective of eating disorder prevention. Our findings suggest that interventions aimed to promote emotional regulation [88] could be included in an integrated program to improve healthy eating habits and reduce BMI [89], as expressed in studies which considered severe obesity and programs of weight loss [36, 47]. The inclusion of emotional skills promotion training in programs focused on the acquisition of healthy eating habits and balanced consumption of nutrients could increase interventions efficacy and reduce drop-out, through a better understanding of the role that emotions play in daily life and by an indirect improvement of self-efficacy. This type of integrated treatment could be as successful as the Mindfulness-based intervention focused on mood and emotional factors related to obesity and emotional eating that allowed an increase in healthy eating behavior [90].

Understanding the emotional components that are linked to obesity could also be useful for designing interventions aimed at reducing compulsive eating behaviors or body weight. Furthermore, the improvement of emotional skills would ameliorate the individual approach to food that could create a more favorable outcome in bariatric surgery [52] and a reduction in the drop-out of diets aimed at reducing BMI, which is very frequently recorded in remission patients.

However, this study presents some limits. One of these limits is the reduced number of participants with obesity that did not allow considering this condition separately from preclinical obesity condition. A significant number of participants with obesity could show higher alexithymia values and worse emotional regulation strategies than overweight people. The possible presence of higher levels of emotional dysregulation in the participants with obesity compared to the participants with preclinical obesity could have emphasized the differences with the control group characterized by normal weight. However, a statistical analysis that considered only participants with preclinical obesity showed results similar to those reported in the present paper. Future studies should focus on analyzing the levels of emotional regulation in both preclinical and clinical obesity, and on trying to highlight possible commonalities and differences in this dimension.

Also, the different proportion of male and female in the two groups could have affected the results. Other studies have reported gender differences in the emotional regulation pattern in people with severe obesity [41], with higher externally oriented thinking in males and higher difficulty identifying feeling in females. Further, most of the previous studies have considered mainly females [12, 39, 49]. This limit should be exceeded in further studies focused on investigating gender differences.

Another limitation is the absence of a longitudinal assessment of the weight variations and emotional adjustment levels among the participants, essential to try to identify a causal direction of this relationship. Furthermore, it could be useful to consider obesity with and without binge eating disorder to evaluate similar and different patterns of emotional dysregulation in both, compared to individuals with overweight and normal weight.

Moreover, the lack of control of some demographic variables, as socio-economic level, and the decision to consider only undergraduate students could represent other limitations on the generalizability of results.

In conclusion, despite the limitations, this study confirms the presence of higher levels of alexithymia in individuals with overweight/obesity. The findings of the present study allow some intriguing suggestions. By considering the aspects related to incorrect eating behavior even in non-clinical populations, this study indicates the importance of evaluating the severity of emotional regulation and the component of emotional management that are involved in the weight increase.

References

WHO obesity and overweight (2016) http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases/obesity/data-and-statistics. Accessed 18 Nov 2018

Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, Schindler K, Busetto L, Micic D (2015) Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the study of obesity. European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obes facts 8(6):402–424

Ricca V, Mannucci E, Moretti S, Di Bernardo M, Zucchi T, Cabras PL, Rotella CM (2000) Screening for binge eating disorder in obese outpatients. Compr Psychiatry 41(2):111–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-440X(00)90143-3

Rothman KJ (2008) BMI-related errors in the measurement of obesity. Int J Obes 32(S3):S56. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.87

Hill AJ (2007) Obesity and eating disorders. Obes rev 8:151–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00335.x

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Pub, Philadelphia

Ramacciotti CE, Coli E, Passaglia C, Lacorte M, Pea E, Dell’Osso L (2000) Binge eating disorder: prevalence and psychopathological features in a clinical sample of obese people in Italy. Psychiat Res 94(2):131–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03353413

Stice E, Bearman SK (2001) Body-image and eating disturbances prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms in adolescent girls: a growth curve analysis. Dev Psychol 37(5):597. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.37.5.597

Svaldi J, Caffier D, Tuschen-Caffier B (2010) Emotion suppression but not reappraisal increases desire to binge in women with binge eating disorder. Psychother Psychosom 79(3):188–190. https://doi.org/10.1159/000296138

Gianini LM, White MA, Masheb RM (2013) Eating pathology, emotion regulation, and emotional overeating in obese adults with binge eating disorder. Eat Behav 14(3):309–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.05.008

Leehr EJ, Krohmer K, Schag K, Dresler T, Zipfel S, Giel KE (2015) Emotion regulation model in binge eating disorder and obesity—a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 49:125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.008

Zijlstra H, van Middendorp H, Devaere L, Larsen JK, van Ramshorst B, Geenen R (2012) Emotion processing and regulation in women with morbid obesity who apply for bariatric surgery. Psyc Health 27(12):1375–1387. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.600761

Gross JJ, Feldman Barrett L (2011) Emotion generation and emotion regulation: one or two depends on your point of view. Emot Rev 3(1):8–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073910380974

Thayer JF, Lane RD (2000) A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. J Affect Disord 61(3):201–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00338-4

Gratz KL, Roemer L (2004) Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 26(1):41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Gross JJ (1998) The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev Gen Psychol 2(3):271. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.25.3.394

Gross JJ (2002) Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 39(3):281–291. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0048577201393198

Denollet J, Rombouts H, Gillebert TC, Brutsaert DL, Sys SU, Stroobant N (1996) Personality as independent predictor of long-term mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Lancet 347(8999):417–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.25.3.394

Gross JJ, Levenson RW (1997) Hiding feelings: the acute effects of inhibiting positive and negative emotions. J Abnorm Psychol 106:95–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.106.1.95

Martin P (1998) The healing mind. Thomas Dunne Books, New York

Denollet J (2005) DS14: standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and type D personality. Psychosom Med 67(1):89–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000149256.81953.49

Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Fang A, Asnaani A (2012) Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression Anxiety 29(5):409–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21888

Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JD (1991) The alexithymia construct: a potential paradigm for psychosomatic medicine. Psychosomatics 32(2):153–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(91)72086-0

Bagby RM, Parker JD, Taylor GJ (1994) The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale—I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res 38(1):23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1

Kauhanen J, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD, Julkunen J, Salonen JT (1996) Alexithymia and risk of death in middle-aged men. J Psychosom Res 41(6):541–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00226-7

Kooiman CG, Bolk JH, Brand R, Trijsburg RW, Rooijmans HG (2000) Is alexithymia a risk factor for unexplained physical symptoms in general medical outpatients? Psychosom Med 62(6):768–778. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200011000-00005

Honkalampi K, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Lehto SM, Hintikka J, Haatainen K, Rissanen T, Viinamäki H (2010) Is alexithymia a risk factor for major depression, personality disorder, or alcohol use disorders? A prospective population-based study. J Psychosom Res 68(3):269–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.010

Kojima M (2012) Alexithymia as a prognostic risk factor for health problems: a brief review of epidemiological studies. BioPsychoSoc Med 6(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0759-6-21

Morie K, Ridout N (2018) Alexithymia and maladaptive regulatory behaviors in substance use disorders and eating disorders. In: Luminet O, Bagby R, Taylor G (eds) Alexithymia: advances in research, theory, and clinical practice. Cambridge University, Cambridge, pp 158–173. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108241595.012

Pinaquy S, Chabrol H, Simon C, Louvet JP, Barbe P (2003) Emotional eating, alexithymia, and binge-eating disorder in obese women. Obes Res 11(2):195–201. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2003.31

Ricca V, Castellini G, Sauro CL, Ravaldi C, Lapi F (2009) Correlations between binge eating and emotional eating in a sample of overweight subjects. Appetite 53(3):418–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2009.07.008

Nowakowski ME, McFarlane T, Cassin S (2013) Alexithymia and eating disorders: a critical review of the literature. J Eat Disord 1:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-2974-1-21

Sasai K, Tanaka K, Hishimoto A (2010) Alexithymia and its relationships with eating behavior, self-esteem, and body esteem in college women. Kobe J Med Sci 56(6):E231–E238

de Zwaan M, Bach M, Mitchell JE, Ackard D, Specker SM, Pyle RL, Pakesch G (1995) Alexithymia, obesity, and binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 17(2):135–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199503)17:2%3c135:AID-EAT2260170205%3e3.0.CO;2-7

Udo T, McKee SA, White MA, Masheb RM, Barnes RD, Grilo CM (2013) Sex differences in biopsychosocial correlates of binge eating disorder: a study of treatment-seeking obese adults in primary care setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 35(6):587–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.07.010

Carriere C, Michel G, Féart C, Pellay H, Onorato O, Barat P, Thibault H (2019) Relationships between emotional disorders, personality dimensions, and binge eating disorder in French obese adolescents. Arch Pediatr 26(3):138–144

Conti C, Di Francesco G, Lanzara R, Severo M, Fumagalli L, Guagnano MT, Porcelli P (2019) Alexithymia and binge eating in obese outpatients who are starting a weight-loss program: a structural equation analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2696

Jansen A, Vanreyten A, van Balveren T, Roefs A, Nederkoorn C, Havermans R (2008) Negative affect and cue-induced overeating in non-eating disordered obesity. Appetite 51(3):556–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.009

Fereidouni F, Atef-Vahid MK, Lavasani FF, Orak RJ, Klonsky ED, Pazooki A (2015) Are Iranian obese women candidate for bariatric surgery different cognitively, emotionally and behaviorally from their normal weight counterparts? Eat Weight Disord 20(3):397–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-014-0168-6

Pink AE, Lee M, Price M, Williams C (2019) A serial mediation model of the relationship between alexithymia and BMI: the role of negative affect, negative urgency and emotional eating. Appetite 133:270–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.11.014

Elfhag K, Lundh LG (2007) TAS-20 alexithymia in obesity, and its links to personality. Scand J Psychol 48(5):391–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00583.x

Behar R, Arancibia M (2014) Alexithymia in eating disorders. Advances in psychology research. Nova Science Publishers, New York, pp 81–108

Racine SE, Horvath SA (2018) Emotion dysregulation across the spectrum of pathological eating: comparisons among women with binge eating, overeating, and loss of control eating. Eat Disord 26(1):13–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2018.1418381

Baldaro B, Rossi N, Caterina R, Codispoti M, Balsamo A, Trombini G (2003) Deficit in the discrimination of nonverbal emotions in children with obesity and their mothers. Int J Obes 27(2):191. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.802228

Da Ros A, Vinai P, Gentile N, Forza G, Cardetti S (2011) Evaluation of alexithymia and depression in severe obese patients not affected by eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord 16(1):24–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03327517

Fukunishi I, Kaji N (1997) Externally oriented thinking of obese men and women. Psychol Rep 80(1):219–224. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.80.1.219-224

Paone E, Pierro L, Damico A, Aceto P, Campanle FC, Silecchia G, Lai C (2019) Alexithymia and weight loss in obese patients underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Eat Weight Disord 24(1):129–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0381-1

Perdue TO, Schreier A, Swanson M, Neil J, Carels R (2018) Majority of female bariatric patients retain an obese identity 18–30 months after surgery. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0601-3

Źak-Gołąb A, Tomalski R, Bąk-Sosnowska M, Holecki M, Kocełak P, Olszanecka-Glinianowicz M, Zahorska-Markiewicz B (2013) Alexithymia, depression, anxiety and binge eating in obese women. Eur Psychiatry 27(3):149–159. https://doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632013000300001

Legorreta G, Bull RH, Kiely MC (1988) Alexithymia and symbolic function in the obese. Psychother Psychosom 50(2):88–94. https://doi.org/10.1159/000288105

Clerici M, Albonetti S, Papa R, Penati G, Invernizzi G (1992) Alexithymia and obesity. Psychother Psychosom 57(3):88–93. https://doi.org/10.1159/000288580

Noli G, Cornicelli M, Marinari GM, Carlini F, Scopinaro N, Adami GF (2010) Alexithymia and eating behaviour in severely obese patients. J Hum Nutr Diet 23(6):616–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01079.x

Speranza M, Loas G, Wallier J, Corcos M (2007) Predictive value of alexithymia in patients with eating disorders: a 3-year prospective study. J Psychosom Res 63(4):365–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.03.008

Wagner A, Aizenstein H, Mazurkewicz L, Fudge J, Frank GK, Putnam K (2008) Altered insula response to taste stimuli in individuals recovered from restricting-type anorexia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology 33(3):513. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301443

Harrison A, Sullivan S, Tchanturia K, Treasure J (2010) Emotional functioning in eating disorders: attentional bias, emotion recognition and emotion regulation. Psychol Med 40(11):1887–1897. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710000036

Fernandes J, Ferreira-Santos F, Miller K, Torres S (2018) Emotional processing in obesity: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. Obes Rev 19(1):111–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12607

World Health Organization. Body mass index—BMI. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi. Accessed May 2019

Bressi C, Taylor G, Parker J, Bressi S, Brambilla V, Aguglia E (1996) Cross validation of the factor structure of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: an Italian multicenter study. J Psychosom Res 41(6):551–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00228-0

Gross JJ, John OP (2003) Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 85(2):348. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Balzarotti S, John OP, Gross JJ (2010) An Italian adaptation of the emotion regulation questionnaire. Eur J Psychol Assess 26(1):61–67. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000009

Garner DM (1991) Eating disorder inventory-2. Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Research, Inc, Odessa

Rizzardi M, Trombini E, Trombini G (1995) EDI-2 eating disorder inventory-2: manuale. O.S. Organizzazioni Speciali, Firenze

Erdfelder E, Faul F, Buchner A (1996) GPOWER: a general power analysis program. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 28:1–11. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03203630

Field A (2005) Discovering statistics using SPSS. Sage Publications, Thousand Oak

Korhonen PE, Seppälä T, Järvenpää S, Kautiainen H (2014) Body mass index and health-related quality of life in apparently healthy individuals. Qual Life Res 23(1):67–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0433-6

Carano A, De Berardis D, Gambi F, Di Paolo C, Campanella D, Pelusi L et al (2006) Alexithymia and body image in adult outpatients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 39(4):332–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20238

Carano A, Totaro E, De Berardis D, Mancini L, Faiella F, Pontalti I et al (2011) Correlazioni tra insoddisfazione corporea, alessitimia e dissociazione nei disturbi del comportamento alimentare. Giornale Italiano di Psicopatologia 17:174–182

Berger SS, Elliott C, Ranzenhofer LM, Shomaker LB, Hannallah L et al (2014) Interpersonal problem areas and alexithymia in adolescent girls with loss of control eating. Compr Psychiatry 55(1):170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.005

Eichen DM, Chen E, Boutelle KN, McCloskey MS (2017) Behavioral evidence of emotion dysregulation in binge eaters. Appetite 111:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.12.021

Jimerson DC, Wolfe BE, Franko DL, Covino NA, Sifneos PE (1994) Alexithymia ratings in bulimia nervosa: clinical correlates. Psychosom Med. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199403000-00002

Beales DL, Dolton R (2000) Eating disordered patients: personality, alexithymia, and implications for primary care. Br J Gen Pract 50(450):21–26

Zonnevijlle-Bendek MJS, Van Goozen SHN, Cohen-Ketteni PT, Van Elburg A, Van Engeland H (2002) Do adolescent anorexia nervosa patients have deficits in emotional functioning? Eur Child Adoles Psy 11(1):38–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007870200006

Eizaguirre AE, de Cabezon AOS, de Alda IO, Olariaga LJ, Juaniz M (2004) Alexithymia and its relationships with anxiety and depression in eating disorders. Pers Indiv Differ 36(2):321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00099-0

Bourke MP, Taylor GJ, Parker JD, Bagby RM (1992) Alexithymia in women with anorexia nervosa: a preliminary investigation. Br J Psychiatry 161(2):240–243. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.161.2.240

Taylor GJ, Parker JD, Bagby RM, Bourke MP (1996) Relationships between alexithymia and psychological characteristics associated with eating disorders. J Psychosom Res 41(6):561–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00224-3

Harrison A, Sullivan S, Tchanturia K, Treasure J (2009) Emotion recognition and regulation in anorexia nervosa. Clin Psychol Psychother 16(4):348–356. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.628

Perry RM, Hayaki J (2014) Gender differences in the role of alexithymia and emotional expressivity in disordered eating. Pers Indiv Differ 71:60–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.07.029

Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT (2001) A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 69(2):317. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.69.2.317

Svaldi J, Griepenstroh J, Tuschen-Caffier B, Ehring T (2012) Emotion regulation deficits in eating disorders: a marker of eating pathology or general psychopathology? Psychiatry Res 197(1):103–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.11.009

Frayn M, Sears CR, von Ranson KM (2016) A sad mood increases attention to unhealthy food images in women with food addiction. Appetite 100:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.008

De Panfilis C, Rabbaglio P, Rossi C, Zita G, Maggini C (2003) Body image disturbance, parental bonding and alexithymia in patients with eating disorders. Psychopathology 36(5):239–246. https://doi.org/10.1159/000073449

Montebarocci O, Codispoti M, Surcinelli P, Franzoni E, Baldaro B, Rossi N (2006) Alexithymia in female patients with eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord St 11(1):14–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03327739

Salminen JK, Saarijärvi S, Äärelä E, Toikka T, Kauhanen J (1999) Prevalence of alexithymia and its association with sociodemographic variables in the general population of Finland. J Psychosom Res 46(1):75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(98)00053-1

Laloyaux J, Fantini C, Lemaire M, Luminet O, Larøi F (2015) Evidence of contrasting patterns for suppression and reappraisal emotion regulation strategies in alexithymia. J Nerv Ment Dis 203(9):709–717. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005751

Swart M, Kortekaas R, Aleman A (2009) Dealing with feelings: characterization of trait alexithymia on emotion regulation strategies and cognitive-emotional processing. PLoS One 4(6):e5751. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005751

McLean CP, Miller NA, Hope DA (2007) Mediating social anxiety and disordered eating: the role of expressive suppression. Eat Disord 15(1):41–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260601044485

Quinton S, Wagner HL (2005) Alexithymia, ambivalence over emotional expression, and eating attitudes. Pers Indiv Differ 38(5):1163–1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.07.013

Mingarelli A, Casagrande M, Benevento M, Stella E, Germanò G, Solano L, Bertini M (2006) Promuovere la capacità di regolazione emozionale negli ipertesi: un’esperienza di psicosalutogenesi (Promoting the ability of emotion regulation in hypertensive patients: an experience of psychological health promotion). Psicologia della Salute 1:137–153

Moreno LA, Gonzalez-Gross M, Kersting M, Molnar D, De Henauw S et al (2008) Assessing, understanding and modifying nutritional status, eating habits and physical activity in European adolescents: the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Study. Public health Nutr 11(3):288–299. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980007000535

O’Reilly GA, Cook L, Spruijt-Metz D, Black DS (2014) Mindfulness-based interventions for obesity-related eating behaviours: a literature review. Obes Rev 15(6):453–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12156

Funding

This work has not supported by any grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology of the University of Rome “Sapienza” (approval number: 0000197) and with the Helsinki declaration.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of topical collection on Personality and eating and weight disorders.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Casagrande, M., Boncompagni, I., Forte, G. et al. Emotion and overeating behavior: effects of alexithymia and emotional regulation on overweight and obesity. Eat Weight Disord 25, 1333–1345 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00767-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00767-9