Abstract

Purpose of the Review

The goal of this review is to describe how a woman’s exposures and experiences lead to Black-white disparities in preterm.

Recent Findings

Studies in the last 10 years have increased knowledge in areas that may explain disparities, in particular social factors such as racism and stress, as well as how social factors at the neighborhood level may intersect with those at the individual level. The biologic pathways linking the social environment to disparities in preterm birth is also becoming better understood. Study designs and measures may need to adapt to effectively study disparities.

Summary

While there is much greater appreciation for the potential importance of the social environment across the life course, more research is needed on methods to best study these factors, particularly in measurement, as well as pathways linking these factors to preterm birth in Black women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Reducing racial and social disparities in key perinatal health outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight, and infant mortality have been national priorities in the USA for decades [1]. Despite efforts to understand the cause(s) of health disparities in infant outcomes, the gap between White and Black mothers/infants has increased [2, 3]. We will review research on how a woman’s exposures and experiences prenatally as well as across her life course are related to disparities in the key pregnancy outcome of preterm birth. We will also describe challenges to studying disparities in birth outcomes and suggest innovative approaches to its study. While the focus of this review will be on the increased risk of preterm birth for Black women in the USA, many of the issues discussed apply to other populations, including other minority groups in the USA and other developed countries, immigrants, and low socioeconomic position individuals.

Risk and Protective Factors Linked to Preterm Birth and Disparities

Research thus far on racial disparities in preterm birth (PTB) has generally focused on whether Black women are more likely to be exposed to risk factors or less likely to experience protective factors. In tandem, there has also been increased attention to the potential for effect modification where similar frequency of exposures by race could produce disparity due to synergy with other exposures. A range of factors have been identified as risk or protective factors that relate to PTB with some of these being particularly salient for Black women. These factors may operate at the individual as well as residential neighborhood level and interact across levels. We first discuss these factors as they relate to exposures and experiences during pregnancy. We then describe contemporary perinatal health frameworks that incorporate the life course and review what is known about these factors in terms of exposures and experiences across the life course and impact on PTB.

Prenatal Factors

Social factors at the individual level were long thought to explain racial disparities. Researchers often suggest that they have “controlled” for differences in socioeconomic status (SES) between Blacks and Whites by including income and education at the time of pregnancy into regression analyses [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11], but such work has generally failed to fully capture all relevant dimensions of SES [9, 12,13,14,15]. Moreover, the historic disenfranchisement of Blacks has produced socioeconomic differences today that are not often ameliorated in one or two generations. While Blacks may now have more opportunities (e.g., education to achieve better employment), the costs of those opportunities may be higher for Black individuals [16]. Related to this, there continues to be well-documented evidence of race influencing financing for homes and vehicles and insurance costs [17, 18]. Even among low-income Black women, while variability in meeting essential needs (e.g., housing, food) may be minimal, there may still be variability in resources for meeting non-essential needs (toys, personal care, restaurant meals). Misra et al. reported that the risk of PTB in a cohort of low-income Black women was doubled for women who lacked resources to meet non-essential needs, even after adjustment for psychosocial factors such as stress [19]. Inclusion of measures of SES beyond education and income may allow for a more complete assessment of SES differences between Blacks and Whites that may underlie disparities in perinatal outcomes [9, 20,21,22,23].

An examination of paternal effects may be particularly salient to consider with regard to persistent and substantial Black-white disparities in birth outcomes in the USA. Structural factors associated with socioeconomic position and discrimination suggest that the contribution and role of paternal factors may be different for Black families [24,25,26,27,28,29]. There may well be paternal risk factors that are relatively more frequent in Black families as well as paternal protective factors that can be identified. Furthermore, the maternal risks to which Black women are exposed may increase vulnerability to paternal factors. We have conceptualized a model to examine how fathers may relate to birth outcomes with a particular focus on Black families [30]. Multiple domains are pertinent to an examination of paternal factors in birth outcomes, including their intersection with maternal factors representing potential mediating and moderating pathways. Evidence is emerging that a range of paternal factors, such as fathers’ attitudes regarding the pregnancy, fathers’ behaviors during the prenatal period, and the relationship between fathers and mothers, may indirectly influence risk for adverse birth outcomes, with implications for potentially explaining racial disparities in this area [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Especially of interest, an evaluation of a program providing comprehensive prenatal services to Black and White adolescent fathers found that fathers’ participation was associated with higher birth weights, a narrowing of racial differences, and a stronger effect on birth weight for the Black infants [33].

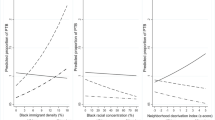

Social factors at the residential neighborhood level have been looked to as potentially important risk factors for racial disparities in adverse perinatal health outcomes, given the strikingly different neighborhoods in which Black and White women reside [56••, 57]. While some studies have demonstrated no associations between neighborhood factors and perinatal outcomes such as PTB, others have reported at least some of the neighborhood factors measured to be associated with selected perinatal outcomes [58,59,60,61,62]. Neighborhood factors linked with perinatal outcomes include unemployment [63,64,65,66,67], crime [65, 68,69,70,71,72,73,74], safety [75, 76], racial composition (%Black) [77,78,79], index of neighborhood deprivation or disadvantage (e.g., Townsend Index) [69, 78, 80,81,82,83], residential stability [70, 84, 85], median rent [78, 86], wealth or affluence [11, 65, 84], median income [87,88,89,90,91], poverty [77, 92, 93], social support [80, 94], and exchange/volunteerism [70, 95]. A meta-analysis found that high neighborhood disadvantage (administratively defined by US Census data) was associated with 27% higher PTB rates, and 11% higher low birth weight rates, compared to neighborhoods with low disadvantage. More recently, studies of perinatal outcomes have begun to utilize data from surveys of individual residents to self-assessments of neighborhood environment with multi-item scales [70, 75, 80]. Perceptions of neighborhood healthy food availability, walkability, safety, social cohesion, and social disorder have all been found to be associated with PTB [96•] as well as with maternal psychosocial factors such as chronic stress and depressive symptoms [73]. Evidence suggests that perceptions of neighborhood disorder and social cohesion are associated with increased inflammation and oxidative stress [97, 98], which may link between neighborhood context and adverse birth outcome in Black women. Future research which incorporates various types of neighborhood context measures [99], especially among Blacks [100], is warranted.

Psychosocial factors have received considerable attention over the past several decades with regard both to the etiology of perinatal outcomes like PTB as well as an explanation for Black-White disparities [101,102,103,104]. Psychosocial factors include racism-related stress as well as other forms of acute and chronic stress. Early work in this area focused on acute stressors; however, the evidence is mixed [105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112]. Later work expanded the conceptualization of stress in pregnancy to include measures of chronic stress [113]. This shift reflects, in part, critiques noting that chronic strain, not recent events, may be more relevant for poor and minority women and give credence for the integration of a life course perspective. In our past research, we have used a brief measure of stress in which the pregnancy is the recall period but the stress reported is likely the result of a mix of acute and chronic stressors. In two past studies of low-income Black women in Baltimore, we have found a significantly increased risk of preterm birth associated with elevated scores on this stress scale [104, 19]. The complex interactions are illustrated by our recent analysis of our LIFE cohort of Black women in the Detroit area; perceived stress and social support were both found to partially mediate the impact of neighborhood quality on depressive symptoms [73].

Interpersonal racism and discrimination can affect many aspects of life which may affect health, such as economic well-being and residential environment. Evidence linking interpersonal racism or racial discrimination to adverse perinatal outcomes is mixed with both null and adverse findings [114,115,116,117,118,119, 120•]. The heterogeneity may be due to differences in conceptualization and measurement [121, 120•, 115]. Minorities may experience interpersonal racism or racial discrimination through significant but acute or discrete, observable life events (e.g., being denied a loan); these are often called major experiences of discrimination [122, 121, 123]. They may also experience interpersonal racism or discrimination via subtle, innocuous degradations or put-downs, called microaggressions [124, 120•]. Stress from interpersonal racism or racial discrimination may be personal experiences or those experienced vicariously or collectively as a minority group [122, 125, 126]. The majority of studies examining the relationship between interpersonal racism or racial discrimination and perinatal outcomes have been focused on the impact of major experiences of discrimination [115, 120•]. Finally, racism cannot be studied separately, as there may be mediation and moderation of its impacts. Using data from the LIFE birth cohort of Black women in the Detroit region, we recently reported that the risk of PTB associated with perceived exposure to racism in the form of microaggressions was moderated by depressive symptoms [120•].

Behavioral factors were also long hypothesized to explain racial disparities in birth outcomes. Cigarette smoking, particularly heavy smoking, is an established risk factor for an increased risk of PTB [127]. However, while this appears to be a risk factor for all women, pregnant Black women smoke at lower rates than Whites [128]. Illicit drug use rates are slightly higher but similar for Blacks and Whites in the USA [129]. Even so, independent effects of drugs on the risk of PTB specifically (not fetal growth restriction) have not been consistently reported absent the potential confounding by cigarette smoking and other contextual factors in the environment [130, 131].

Obesity may be another factor relating to disparities in PTB; Black women are more likely to be obese than White women [132, 133]. While recent studies have reported increased risks of PTB among obese women [134,135,136], results overall have been inconsistent across various studies, obesity subtypes, and PTB outcomes [137]. This particular risk factor may best be examined as a trajectory across a woman’s life rather than a state at conception, particularly for Black women who are more likely to be born growth restricted than White women [138].

Physical activity has emerged recently as a possible protective factor for PTB relevant for all women. It may be especially important for Black women, in whom physical activity is infrequent before [139] and during pregnancy [140]. While evidence on physical activity and PTB has expanded considerably in the past three decades, most studies were comprised of White women [141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148] and reported a reduction in PTB risk [149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156, 144, 145] or a null effect [157, 141,142,143, 146, 147]. The few studies in large cohorts of Black women [158,159,160] suggest that increasing physical activity could contribute to a significant reduction in PTB among Black women. While the research is encouraging, a number of methodological issues (e.g., measures, threshold effects for timing, and intensity) need to be addressed to reach a more definitive result that can support development of physical activity interventions to reduce PTB. This is especially true of the research on Black women specifically, given the very small number of studies.

Life Course Factors

Epidemiologic research on a wide range of outcomes now examines how factors across the life course, either through accumulation or exposures during critical periods, impact later risk. Since the publishing of seminal papers in the early 2000s [161,162,163] that advocated for the integration of a life course perspective into maternal and child health research, scholarly work has expanded to include exposures in the year prior to conception [164, 165]. But intergenerational effects of events and experiences occurring along the maternal life span—starting in early childhood—on perinatal outcomes of women’s offspring remain less studied as are the mechanisms by which these life course factors evoke distal effects. The few extant intergenerational studies suggest that events and experiences occurring across a woman’s life course may have an effect on future perinatal outcomes [166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185], and these factors have not been fully evaluated in the literature seeking to explain racial differences [20, 181, 186,187,188,189]. Exposures and experiences beginning before the prenatal period include social factors and maternal adiposity.

Social Factors: Individual Level

Intergenerational studies suggest that the individual level social environment in infancy and childhood has an effect on future reproductive outcomes [166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175, 177]. As yet, studies have considered only birth weight outcomes and not preterm birth. Misra et al., using data which followed the children and grandchildren of women enrolled (1959–1965) in the Baltimore, MD site of the National Collaborative Perinatal Project, found women’s in utero exposure to smoke affected the birth weight of their offspring [190]. Maternal SES in childhood and adulthood also each made independent contributions to infant birth weight [191]. Using data from the Pregnancy Outcomes and Community Health Study (1998–2004), Slaughter et al. found that infants born to women whom moved upward in their socioeconomic position between childhood and adulthood had a reduced probability of being small-for-gestation when compared to infants born to women who stayed at the lower socioeconomic position across their life course [176]. Collins et al. also investigated the role of the father’s lifelong socioeconomic position and reported that it contributed substantially to the Black-white disparity in low birth weight [192•]. While the cohorts from these studies included White women, Black women were included in substantial numbers. More recently, our team examined SES trajectories among women in our LIFE birth cohort comprised only of Black women. Women who had upward mobility, compared to women whose trajectory remained at the lower static SES, had a reduced risk of their offspring being small-for-gestation [176].

Racism may also influence PTB through experiences that occur across a woman’s lifetime and before conception and not just through incidents occurring during her pregnancy. In our cohort of low-income Black women in Baltimore, lifetime racism scores above the median (more racism) were associated with an increased risk of preterm birth in three subgroups with the effect moderated by depressive symptoms and stress [19]. This is an important reminder that social and psychosocial factors may operate in a complex manner related to risk of PTB, particularly for Black women.

Social Factors: Neighborhood Level

Few studies have been published on the influence of residential neighborhood social environment across the maternal life course on risk for adverse birth outcomes generally or for Black families. Studies investigating neighborhood effects on perinatal health outcomes have been predominantly cross sectional in nature [56••, 193, 89, 194,195,196, 85, 197,198,199,200, 69]. While there have been exceptions—in the USA, these include the work of Collins and David [177, 179, 185, 201, 180] as well as Kramer [202]—such studies have relied on vital statistics to create their birth cohorts. While vital records allow for the construction of large cohorts for life course research and may increase generalizability, they have several limitations. Studies using vital statistic data are susceptible to inaccurate clinical information [203] and are limited in their ability to control for relevant sociodemographic confounders and to investigate mechanisms that connect residential neighborhood across the life course to perinatal outcomes, as vital statistics lack the “granular information” that can be collected through interviews, record abstraction, and biospecimen collection. Furthermore, cross-sectional ascertainment may not accurately reflect social environments at the neighborhood level since neighborhoods are shaped by economic, social, and political forces exerted over several decades [204•, 205, 206]. Static measures of the neighborhood environment are likely biased toward the null, because they cannot account for the potential indirect effects through time-varying characteristics of families, including structure, occupation, income, and marital status [207]. Hence, there remains a knowledge gap regarding the historical, life course, or cumulative impacts of maternal exposures to neighborhood social environment on perinatal health.

Pathways Linking Risk and Protective Factors to Birth Outcomes and Disparities

There has long been research on the final biologic pathways in the pathogenesis of PTB. There has, however, been little success in modifying these proximate triggers, once identified. While successful prevention requires knowledge of the more distal (prenatal and life course) determinants, the pathways between such factors and the final biologic triggers must also be studied. Research needs to consider not only how distal factors affect risk but also how downstream factors may mediate and/or moderate their impact.

Systemic inflammation during pregnancy is one of these downstream factors through which the distal determinants may impact birth outcomes. During pregnancy, the immune functions are regulated by a complex array of cytokines [208, 209]. Mid-pregnancy is a predominantly anti-inflammatory phase which contributes to the maintenance of pregnancy [209, 208, 210]. Toward the end of pregnancy, however, there is a switch from anti-inflammatory to pro-inflammatory pathways which stimulate uterine contractions resulting in cervical ripening, rupture of membranes, labor, and birth [209, 208, 211, 210]. Chronic stress, however, can activate these pro-inflammatory pathways earlier in pregnancy by an increase release of cortisol from the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Cortisol is potently anti-inflammatory, and normally, activation of the HPA axis counter-regulates immuno-inflammatory responses [211, 212]. However, during chronic stress, cortisol is less effective in regulating the inflammatory responses, and therefore, there may be a shift of the immune system into a pro-inflammatory state earlier than normal which can increase the risk of PTB [209, 211, 213, 208]. Findings from small studies suggest that pregnant women with higher levels of stress have higher levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines and lower levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines [213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222]. Studies have also found that women with PTB have higher levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines as early as the mid-pregnancy compared with women with term birth [223,224,225,226,227,228,229, 218, 230, 215, 231, 232, 217, 233,234,235,236,237,238]. Interestingly, Black pregnant women have higher hair cortisol [239], a novel biomarker of chronic stress [240, 241], and systemic inflammation [242, 243] than Whites, suggesting that they experience higher chronic stress. In one study, Black women with PTB had higher systemic inflammation than those with term births; such differences were not observed in Whites [229]. These findings support the hypothesis that chronic cumulative exposure to stress experienced by Black women may increase their systemic inflammation and ultimately risk for PTB. Indeed, we found that Black women who reported racial discrimination had higher serum levels of interleukin(IL)-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, compared with women who did not experience racial discrimination [244]. Thus, systemic inflammation is a potential pathway by which social factors increase the risk of negative birth outcomes.

Omics during pregnancy is a very new area of research with regard to the biologic pathways that underlie the pathogenesis of PTB. Publications on omics and PTB thus far have primarily considered the role of the maternal proteome [245] and microbiome [246]. The lipidome and metabolome have also begun to be investigated. Studies in proteomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics have generally been small, and replication of results continues to be a challenge [245]. The published literature on the lipidome and metabolome has not yet been sufficient to merit a review, but studies have begun to appear that suggest associations with PTB [247, 248]. Considerably more studies of the microbiome and PTB, particularly the vaginal microbiome, have been published in the past decade, but there is still little consensus and replication of results across studies.

There has been little attention to racial and ethnic heterogeneities and how omic factors may relate to PTB among Black women specifically or explain the racial disparity. Furthermore, few omic studies have included diverse samples with sizeable numbers of pregnant Black women to allow for race-specific analysis. While the 2016 report of Saade et al.’s proteomic study [249] included approximately 900 Black women within the cohort of 4509 pregnant women followed to delivery, the cohort was low risk (<5% rate of PTB), and none of the results were stratified on race. In recent work on the vaginal microbiome, we reported that a number of bacterial species were each associated with an increased risk of PTB in heterogeneous cohort than included approximately equal numbers of Black, Hispanic, and White women. Most strikingly, the racial/ethnic group modified nearly all of these associations with PTB, with the effect of specific taxa on risk as well as the prevalence of the taxa varying by racial/ethnic group [250].

Epigenetic factors are another potential pathway, defined as molecular modifications that alter gene activity but do not change the sequence of the gene [251]. DNA methylation and histone modifications, the two most studied types of epigenetic processes [252], have been shown to be responsive to early-life environmental exposures in various gene regions [253]. Epigenetics and its subjectivity to environmental influences during developmental stages of pregnancy hold the potential for the discovery of biomarkers to identify women at risk for adverse birth outcomes [254]. Several studies have discovered differences in DNA methylation in mothers experiencing PTB and maternal stress [255,256,257]. Finally, Salihu et al. (2016) [258] identified gene methylation sites that showed significant differences between Black and non-Black newborns. Studies in the causes and implications of epigenetic changes and differences are in their infancy, but they may well lead to the discovery of biomarkers or the ability to gauge intergenerational risks and significantly decrease negative birth outcomes.

Innovative Approaches to Study Design and Analytic Methods to Study Vulnerable and Marginalized Populations

We describe in this final section proposed innovative approaches to study design and measurement that are needed to advance research in this area.

Black-Only Study Design

While the “environment” for a woman certainly differs by race in the USA, variability of pregnancy outcomes and exposures within the subpopulation of Black women often goes unexamined when research focuses on Black-white comparisons. Understanding the causes of the disparity and identifying solutions requires studies which examine risk and protective factors within the population of Black women. While countless studies have reported on the disparity in adverse birth outcomes, most have relied on vital statistics or institutional databases. Studies which have engaged in primary collection of data on risk and protective factors have rarely included Black respondents in numbers sufficient for analyses to stratify on race. This is critical for the study of factors that may be unique to Black women, such as the experience of racism, or when the assessment of effect modification is an aim. We have repeatedly found evidence that effects of such factors are indeed complex and are modified and mediated by other factors [259, 104, 19, 120•, 122, 125, 126].

Beyond studying unique factors and interactions, we also argue that restriction is necessary to address the fundamental incommensurability of measures of social environmental exposures for Blacks and Whites [260]. As reviewed by Kaufman [260], adjusting for education is an insufficient control of socioeconomic differences because education does not produce the same material benefits for Blacks as for Whites with wealth and income inequities pervasive within educational strata. Incommensurate measures are liable to produce residual confounding. Furthermore, stratification and multiple regression techniques cannot accommodate the extreme confounding likely to occur for factors such as racism where the distribution of the variables may widely vary and therefore produce empty cells.

Finally, we turn to the literature on counterfactuals to understand the fundamental difficulty in employing White women as a comparison group. The adequacy of a comparison group rests upon its ability to yield an accurate estimate of the risk that would have been experienced by the exposed group in the absence of the exposure [261, 262]. Kaufman and colleagues articulate this problem with regard to a hypothetical study of gender and depression. “On the basis of the underlying counterfactual interpretation of this approach, the researcher would in fact be posing the query, ‘What would the risk of depression have been for this individual had she not been a woman?’ While an adequate explication of this argument requires substantially more detail, it suffices in this context to note that causal inference related to essential attributes, rather than modifiable states, raises insoluble problems…” [260]. Race is similarly problematic; in that, the pathways we propose to study have no plausible counterpart for women who are not Black. Morgenstern asks, “…do we want to compare the observed outcome risk in a Black population with what the risk would have been if everyone in this population would have been born White? …What variables or conditions would we want to hold constant to assess this contrast—the race of their parents or ancestors, their sociocultural heritage, their educational and occupational achievements or opportunities, their experience with discrimination or injustice…” [263].

Timing of Cohort Recruitment

Cohorts established prospectively often recruit from prenatal clinics which may lead to a bias toward women who have early and/or consistent prenatal care and whom have lower-risk profiles than women who are unable to be recruited due to multiple missed prenatal care appointments, late, interrupted, or sporadic care [264,265,266,267,268]. Investigators have consistently demonstrated that women who receive inadequate prenatal care are at increased risk for adverse perinatal outcomes [264,265,266,267,268]. While prenatal care may not be the causal factor influencing outcomes, it is a marker for risk in the population of pregnant women.

If these subgroups of women are systematically more likely to be excluded by this particular design, two problems may arise. First, the prevalence of the exposure and/or outcome may differ. Prior studies suggest that participants in a prospective cohort study of pregnancy are lower risk in terms of both exposures and rate of PTB. For example, in our Baltimore study (2000–2004) [120•], our postpartum recruited group included women with late or no prenatal care as well as women with care who we had been unable to reach prenatally. Women recruited postpartum had a higher PTB rate as well as being more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors. Findings from a large-scale carefully conducted prospective cohort study, known as the Pregnancy, Infection, and Nutrition (PIN) study, also demonstrate the potential problem with this design. PIN recruited women prenatally from clinical sites. PIN PTB rates were compared to rates from vital statistics for the corresponding population. For Whites, PIN participants were at similar risk for PTB. For Blacks, PIN participants experienced substantially lower PTB rates than area women [269]. The sample of women recruited with this design were at lower risk, which may have effects on both understanding etiology among higher-risk women as well as constraining predicted statistical power to detect effects of exposures.

Second, a prospective cohort design may result in bias such that the relation between exposure and disease is different for those who participate and those who would theoretically be eligible for the study but do not participate [262, 270]. Eligibility might be defined with respect to receipt of consistent prenatal care but ideally would relate only to pregnant women from the underlying population. Recent analyses of the PIN study again make the point that concern about heterogeneity in effect estimates may be warranted. While Black women in the community were nearly two times more likely to deliver preterm than White women, PTB rates were similar for Black and White women enrolled in PIN. Differences were even more pronounced for very PTB. The association (stratified by race) between maternal education and PTB also varied, with little effect of education on PTB among Black PIN participants but a protective effect among Black women in the area community [269].

The preference for prospective studies beginning earlier in pregnancy, often referred to as the gold standard, has not taken account of the limitations described here. This reliance has stemmed in part from the interest in developing prenatal biomarkers of risk that can be used to identify and then intervene with women prior to development of adverse birth outcomes. Certainly, studies recruiting women at birth cannot study biomarkers that could be used to screen women clinically. However, biologic measures collected at delivery can reflect exposures that occur prenatally. The placenta is a source of biologic data that provides a window on exposures beginning even early in pregnancy [271]. Another potential biomarker that can be collected postpartum and provide a measure from the prenatal period is hair cortisol. Hair cortisol is less subject to daily fluctuation than salivary cortisol and a novel biomarker of chronic stress [240, 241] that could capture exposures across the pregnancy.

Beyond Prenatal Care: Alternative Recruitment Sites

It is challenging to recruit pregnant women through prenatal care in such a manner that it results in an unbiased and generalizable sample. This is obviously critical for Black women who are less likely to receive adequate and timely prenatal care. We have undertaken one approach which recruits women at the point of delivery and collects data by interview and record abstraction. While new laboratory assessment methods may enable biologic measures to be collected postpartum that can reflect prenatal exposure, ideally, approaches are also needed to recruit pregnant women outside of prenatal care settings. One approach still linked to care seeking would be to screen and recruit during emergency department encounters. Even with the tremendous expansions of public insurance coverage and subsidies for care, women, particularly low-income and minority women, continue to seek care from emergency departments in large numbers.

Measurement to Assess Cumulative and Life Course Exposures

Attention is increasingly being given to the potential importance of cumulative and life course exposures that may relate to adverse birth outcomes and Black/White disparities to prospectively follow participants across their life span as well as intergenerationally requires time and resources that may not exist. Potentially external data, such as collected in surveys or vital record registration, could be used to provide data across the life course and across generations. Such an approach was taken by Collins et al. [192•] to examine the impact of maternal and paternal early social environment on birth outcomes of the next generation. Parental proxies may be an efficacious alternative to capturing a range of exposures occurring in the early childhood of individual’s life span. Yet, only a handful of life course perinatal epidemiologic studies have incorporated the use of proxy reporting by mothers of women (grandmother of the index child) to collect women’s early childhood exposures and outcomes [272,273,274,275,276]. In the LIFE cohort, we utilized both proxy- and self-reporting to ascertain information related to the social, psychosocial, and biomedical environment across the maternal life course [276, 275••]. Our validation study showed positive associations between LIFE women and their mother’s retrospective reports for the body weight, health, and socioeconomic position during LIFE women’s childhood [276]. We also considered residential environment derived from addresses and perceptions over the life course, comparing subjective to objective data [275••] and comparing reports from mothers and grandmothers (unpublished results). Longitudinal data could allow investigators to take into account the accumulation of exposures across neighborhoods, with a multiple membership model, or separating out the effect of different kinds of neighborhood exposures with a cross-classified model [277]. Our findings suggest that retrospective reports of individual and neighborhood environments may be a cost-effective, valid, and reliable method to examine how the social environment over the maternal life course may independently, cumulatively, and interactively impact perinatal outcomes.

Biologic measures may enable the integration of early and cumulative exposures. Telomere length has increasingly been examined as one such biomarker. Telomere attrition occurs with age but may be accelerated by chronic psychological stress [278,279,280]. Evidence has shown telomere shortening to be a predictor of health status and longevity [281, 282]. A recent study found that perceptions of neighborhood context was associated with shorter telomere length, even after controlling for individual level covariates, among Black women, but not men [283]. Epigenetic modifications, discussed briefly in our prior section on pathways, may also act as biomarkers of exposure to stressors across the life course [284]. Changes in DNA methylation across the life course and in response to acute stress have been documented [285]; however, the degree to which lifelong psychosocial stressors impact DNA methylation and pregnancy outcomes remains understudied.

Conclusion

While promising research is emerging, efforts to identify strategies to reduce risk require a better understanding of the problem and its causes. We need bold research that encompasses the complexity of women’s lives in the context of their family, community, and nation and her experiences and exposures are over her life course. Changes at the individual, community, and national level are needed to close the gap and eliminate disparities in PTB.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Guyer B, Freedman MA, Strobino DM, Sondik EJ. Annual summary of vital statistics: trends in the health of Americans during the 20th century. Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1307–17.

Mathews T, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(9):1–28.

Singh GK, van Dyck PC. Infant mortality in the United States, 1935–2007. M a CHB Health Resources and Services Administration (Ed) Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services. 2010.

Berkowitz GS. An epidemiological study of preterm delivery. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;113:81–92.

Fedrick J, Anderson ABM. Factors associated with spontaneous preterm birth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1976;83:342–50.

Lumley J. How important is social class a factor in preterm birth? Lancet. 1997;349:1040–1.

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75–84. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60074-4.

Culhane JF, Goldenberg RL, editors. Racial disparities in preterm birth. Seminars in perinatology; 2011: Elsevier.

Dennis EF, Webb DA, Lorch SA, Mathew L, Bloch JR, Culhane JF. Subjective social status and maternal health in a low income urban population. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(4):834–43.

Lorch SA, Enlow E. The role of social determinants in explaining racial/ethnic disparities in perinatal outcomes. Pediatr Res. 2016;79(1–2):141–7. doi:10.1038/pr.2015.199.

Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, Cubbin C, Braveman PA. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(3):263–72.

Collins JW, David RJ. The differential effect of traditional risk factors on infant birth weight among Blacks and Whites in Chicago. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:679–81.

Shiono PH, Klebanoff MA. Ethnic differences in preterm and very preterm delivery. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:1317–21.

Kaufman J, Cooper R, McGee D. Socioeconomic status and health in Blacks and Whites: the problem of residual confounding and the resiliency of race. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass). 1997;8(6):621.

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294(22):2879–88. doi:10.1001/jama.294.22.2879.

Shapiro T, Meschede T, Osoro S. The roots of the widening racial wealth gap: explaining the Black-white economic divide. Institute on Assets and Social Policy. 2013.

Squires GD. Capital and communities in Black and White: the intersections of race, class, and uneven development. New York, NY: State University of New York Press; 1994.

Ghent AC, Hernandez-Murillo R, Owyang MT. Differences in subprime loan pricing across races and neighborhoods. Reg Sci Urban Econ. 2014;48:199–215.

Misra D, Strobino D, Trabert B. Effects of social and psychosocial factors on risk of preterm birth in Black women. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2010;24(6):546–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01148.x.

Misra DP. Racial disparities in perinatal health: a multiple determinants perinatal framework with a lifespan approach. Harvard Health Policy Review. 2006;7(1):72–90.

Singh-Manoux A, Marmot MG, Adler NE. Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):855–61.

Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG. Subjective social status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(6):1321–33.

Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy. White women Health psychology. 2000;19(6):586.

Bowman P. Black fathers and the provider: role strain, informal coping resources, and life happiness. In: Boykin W, editor. Empirical research in Black psychology. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1985. p. 9–19.

Bowman P. The impact of economic marginality on African American husbands and fathers. In: McAdoo H, editor. Family ethnicity. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. p. 120–37.

Cochran D. African American fathers: a decade review of the literature. Fam Soc. 1997;78:340–51.

Nelson T. Low-income fathers. Annual Review of Sociology. 2004;30:427–51.

Testa M, Astone N, Krogh M, Neckerman K. Employment and marriage among inner-city fathers. In: Wilson W, editor. The ghetto underclass. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications Inc.; 1993. p. 96–108.

Wade J. African American fathers and sons: social, historical, and psychological considerations. Families in Society 1994;. 1994;75:561–70.

Misra DP, Caldwell C, Young Jr AA, Abelson S. Do fathers matter? Paternal contributions to birth outcomes and racial disparities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(2):99–100. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.11.031.

Abel EL, Kruger M, Burd L. Effects of maternal and paternal age on Caucasian and native American preterm births and birth weights. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19(1):49–54.

Astolfi P, De Pasquale A, Zonta LA. Paternal age and preterm birth in Italy, 1990 to 1998. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass ). 2006;17(2):218–21.

Barth R, Claycomb M, Loomis A. Services to adolescent fathers. Health Soc Work. 1988;13:277–87.

Basso O, Olsen J, Christensen K. Recurrence risk of congenital anomalies the impact of paternal social and environmental factors: a population based study in Denmark. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(6):598–604.

Chen X-K, Wen SW, Krewski D, Fleming N, Yang Q, Walker MC. Paternal age and adverse birth outcomes: teenager or 40+, who is at risk? Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2008;23(6):1290–6.

Comstock GW, Lundin FE. Paternal smoking and perinatal mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98:708–18.

Croen LA, Najjar DV, Fireman B, Grether JK. Maternal and paternal age and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2007;161(4):334–40.

Fursternberg F, Harris K. When and why fathers matter: impacts of father involvement on the children of adolescent mothers. In: Lerman R, Ooms T, editors. Young unwed fathers: Changing roles and emerging policies. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1993. p. 117–38.

Gaudino JJ, Jenkins B, Rochat R. No fathers’ names: a risk factor for infant mortality in the state of Georgia. USA Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:253–65.

Haug K, Irgens LM, Skjaerven R, Markestad T, Baste V, Schreuder P. Maternal smoking and birthweight: effect modification of period, maternal age and paternal smoking. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79(6):485–9.

Jaquet D, Swaminathan S, Alexander GR, Czernichow P, Collin D, Salihu HM, et al. Significant paternal contribution to the risk of small for gestational age. BJOG. 2005;112(2):153–9.

Lie RT, Wilcox AJ, Skjaerven R. Maternal and paternal influences on length of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(4):880–5.

Malaspina D, Harlap S, Fennig S, Heiman D, Nahon D, Feldman D, et al. Advancing paternal age and the risk of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(4):361–7.

Malaspina D, Reichenberg A, Weiser M, Fennig S, Davidson M, Harlap S, et al. Paternal age and intelligence: implications for age-related genomic changes in male germ cells. Psychiatr Genet. 2005;15(2):117–25.

Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM. The effect of paternal smoking on the birthweight of newborns whose mothers did not smoke. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1489–91.

Nahum GG, Stanislaw H. Relationship of paternal factors to birth weight. J Reprod Med. 2003;48(12):963–8.

Padilla Y, Reichman N. Low birth weight: do unwed fathers help? Child Youth Serv Rev. 2001;23:427–52.

Parker JD, Schoendorf KC. Influence of paternal characteristics on the risk of low birth weight. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:399–407.

Reichman NE, Teitler JO. Paternal age as a risk factor for low birthweight. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):862–6.

Savitz DA, Schwingl PJ, Keels MA. Influence of paternal age, smoking, and alcohol consumption on congenital anomalies. Teratology. 1991;44(4):429–40.

Shea KM, Little RE, Team AS. Is there an association between preconceptional paternal X-ray exposure and birth outcome. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:546–51.

Tough SC, Faber AJ, Svenson LW, Johnston DW. Is paternal age associated with an increased risk of low birthweight, preterm delivery, and multiple birth? Can J Public Health. 2003;94(2):88–92.

Wannamethee SG, Lawlor DA, Whincup PH, Walker M, Ebrahim S, Davey-Smith G. Birthweight of offspring and paternal insulin resistance and paternal diabetes in late adulthood: cross sectional survey. Diabetologia. 2004;47(1):12–8.

Young A, Holcomb P. Voices of young fathers: the partners for fragile families demonstration projects: the urban Institute’s Center on Labor, Human Services, and Population2007 June 2007.

Zhang J, Ratcliffe JM. Paternal smoking and birthweight in Shanghai. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:207–10.

•• Ncube CN, Enquobahrie DA, Albert SM, Herrick AL, Burke JG. Association of neighborhood context with offspring risk of preterm birth and low birthweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:156–64. The authors examined associations of neighborhood disadvantage with preterm birth and low birthweight and explored differences in relationships among racial groups. The review of the literature and meta-analyses support an association between neighborhood disadvantage and both PTB and LBW but associations may differ by race

Metcalfe A, Lail P, Ghali WA, Sauve RS. The association between neighbourhoods and adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of multi-level studies. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011;25(3):236–45.

Culhane JF, Elo IT. Neighborhood context and reproductive health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5 Suppl):S22–9.

Ellen IG, Mijanovich T, Dillman K-N. Neighborhood effects on health: exploring the links and assessing the evidence. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2001;23(3–4):391–408.

Rajaratnam J, Burke J, O’Campo P. Maternal and child health and neighborhood context: the selection and construction of area-level variables. Health & Place. 2006;12(4):547–56.

Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(2):111–22.

Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol Bull. 2000;126(2):309–37.

Ahern J, Pickett KE, Selvin S, Abrams B. Preterm birth among African American and White women: a multilevel analysis of socioeconomic characteristics and cigarette smoking. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(8):606–11.

Pickett KE, Ahern JE, Selvin S, Abrams B. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, maternal race and preterm delivery: a case-control study. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(6):410–8.

O’Campo P, Xue X, Wang MC, Caughy M. Neighborhood risk factors for low birthweight in Baltimore: a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(7):1113–8.

Grewal J, Carmichael SL, Song J, Shaw GM. Neural tube defects: an analysis of neighbourhood- and individual-level socio-economic characteristics. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23(2):116–24.

Luo Z-C, Wilkins R, Heaman M, Martens P, Smylie J, Hart L, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics, birth outcomes and infant mortality among first nations and non-first nations in Manitoba, Canada. The open women’s health journal. 2010;4:55.

Messer LC, Kaufman JS, Dole N, Herring A, Laraia BA. Violent crime exposure classification and adverse birth outcomes: a geographically-defined cohort study. Int J Health Geogr. 2006;5:22.

Messer LC, Kaufman JS, Dole N, Savitz DA, Laraia BA. Neighborhood crime, deprivation, and preterm birth. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(6):455–62.

Morenoff JD. Neighborhood mechanisms and the spatial dynamics of birth weight. Ajs. 2003;108(5):976–1017.

Zapata B, Rebolledo A, Atalah E, Newman B, King M. The influence of social and political violence on the risk of pregnancy complications. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:685–90.

Collins Jr JW, David RJ. Urban violence and African-American pregnancy outcome: an ecologic study. Ethn Dis. 1997;7(3):184–90.

Giurgescu C, Misra DP, Sealy-Jefferson S, Caldwell CH, Templin TN, Slaughter-Acey JC, et al. The impact of neighborhood quality, perceived stress, and social support on depressive symptoms during pregnancy in African American women. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:172–80.

Schempf A, Strobino D, O’Campo P. Neighborhood effects on birthweight: an exploration of psychosocial and behavioral pathways in Baltimore, 1995–1996. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(1):100–10.

Collins Jr JW, David RJ, Symons R, Handler A, Wall S, Andes S. African-American mothers’ perception of their residential environment, stressful life events, and very low birthweight. Epidemiology. 1998;9(3):286–9.

Bermúdez-Millán A, Damio G, Cruz J, D’Angelo K, Segura-Pérez S, Hromi-Fiedler A, et al. Stress and the social determinants of maternal health among Puerto Rican women: a CBPR approach. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(4):1315.

Grady SC. Racial disparities in low birthweight and the contribution of residential segregation: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(12):3013–29.

Roberts EM. Neighborhood social environments and the distribution of low birthweight in Chicago. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(4):597–603.

Herd D, Gruenewald P, Remer L, Guendelman S. Community level correlates of low birthweight among African American, Hispanic and White women in California. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(10):2251–60.

Buka SL, Brennan RT, Rich-Edwards JW, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhood support and the birth weight of urban infants. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(1):1–8.

Janghorbani M, Stenhouse E, Millward A, Jones RB. Neighborhood deprivation and preterm birth in Plymouth. UK J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19(2):85–91.

Collins Jr JW, Simon DM, Jackson TA, Drolet A. Advancing maternal age and infant birth weight among urban African Americans: the effect of neighborhood poverty. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):180–6.

Ma X, Fleischer NL, Liu J, Hardin JW, Zhao G, Liese AD. Neighborhood deprivation and preterm birth: an application of propensity score matching. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(2):120–5.

English PB, Kharrazi M, Davies S, Scalf R, Waller L, Neutra R. Changes in the spatial pattern of low birth weight in a Southern California county: the role of individual and neighborhood level factors. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(10):2073–88.

Janevic T, Stein CR, Savitz DA, Kaufman JS, Mason SM, Herring AH. Neighborhood deprivation and adverse birth outcomes among diverse ethnic groups. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(6):445–51.

Meng G, Thompson ME, Hall GB. Pathways of neighbourhood-level socio-economic determinants of adverse birth outcomes. Int J Health Geogr. 2013;12(1):1.

Luo ZC, Kierans WJ, Wilkins R, Liston RM, Mohamed J, Kramer MS. Disparities in birth outcomes by neighborhood income: temporal trends in rural and urban areas, British Columbia. Epidemiology. 2004;15(6):679–86.

Kaufman JS, Dole N, Savitz DA, Herring AH. Modeling community-level effects on preterm birth. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(5):377–84.

Farley TA, Mason K, Rice J, Habel JD, Scribner R, Cohen DA. The relationship between the neighbourhood environment and adverse birth outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20:188–200.

Geronimus AT. Black/White differences in the relationship of maternal age to birthweight: a population-based test of the weathering hypothesis. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42(4):589–97.

Shankardass K, O’Campo P, Dodds L, Fahey J, Joseph K, Morinis J, et al. Magnitude of income-related disparities in adverse perinatal outcomes. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014;14(1):96.

Rauh VA, Andrews HF, Garfinkel RS. The contribution of maternal age to racial disparities in birthweight: a multilevel perspective. [see comment]. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1815–24.

Young RL, Weinberg J, Vieira V, Aschengrau A, Webster TF. A multilevel non-hierarchical study of birth weight and socioeconomic status. Int J Health Geogr. 2010;9(1):1.

Nkansah-Amankra S, Dhawain A, Hussey JR, Luchok KJ. Maternal social support and neighborhood income inequality as predictors of low birth weight and preterm birth outcome disparities: analysis of South Carolina pregnancy risk assessment and monitoring system survey, 2000–2003. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(5):774–85.

Auger N, Park AL, Gamache P, Pampalon R, Daniel M. Weighing the contributions of material and social area deprivation to preterm birth. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(6):1032–7.

• Sealy-Jefferson S, Giurgescu C, Helmkamp L, Misra DP, Osypuk TL. Perceived physical and social residential environment and preterm delivery in African-American women. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(6):485–93. Perceptions of the residential environment may be associated with preterm delivery (PTD), though few studies exist. No significant associations between perceived residential environment and preterm birth were found overall but preterm birth rates of women with lower education were significantly affected by the perceived physical and social residential environment

Schulz AJ, Mentz G, Lachance L, Johnson J, Gaines C, Israel BA. Associations between socioeconomic status and allostatic load: effects of neighborhood poverty and tests of mediating pathways. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1706–14. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300412.

Nazmi A, Diez Roux A, Ranjit N, Seeman TE, Jenny NS. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of neighborhood characteristics with inflammatory markers: findings from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Health Place. 2010;16(6):1104–12. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.07.001.

Schootman M, Nelson EJ, Werner K, Shacham E, Elliott M, Ratnapradipa K, et al. Emerging technologies to measure neighborhood conditions in public health: implications for interventions and next steps. Int J Health Geogr. 2016;15(1):20. doi:10.1186/s12942-016-0050-z.

Sealy-Jefferson S, Messer L, Slaughter-Acey J, Misra DP. Inter-relationships between objective and subjective measures of the residential environment among urban African American women. Ann Epidemiol. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.12.003.

Hogue CJR, Hargraves MA. Preterm birth in the African-American community. Semin Perinatol. 1995;19:255–62.

Rich-Edwards J, Krieger N, Majzoub J, Zierler S, Lieberman E, Gillman M. Maternal experiences of racism and violence as predictors of preterm birth: rationale and study design. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15(Suppl 2):124–35.

McLean DE, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Wingo PA, Floyd RL. Psychosocial measurement: implications for study of preterm delivery in Black women. Am J Prev Med. 1993;9(6 suppl):39–81.

Misra D, O’Campo P, Strobino D. Testing a sociomedical model for preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15(2):110–22.

Copper R, Goldenberg R, Das A, et al. The preterm prediction study: maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1286–92.

Dole N, Savitz D, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz A, McMahon M, Buekens P. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:14–24.

Dunkel-Schetter C. Maternal stress and preterm delivery. Prenatal and Neonatal Medicine. 1998;3:39–42.

Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Sabroe S, et al. Psychological distress and preterm delivery. BMJ. 1993;307:234–9.

Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Secher NJ, Hatch MC, Sabroe S. Do stressful life events affect duration of gestation and risk of preterm delivery? Epidemiology. 1996;7:339–45.

Hoffman S, Hatch M. Stress social support and pregnancy outcome: a reassessment based on recent research. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1996;10:380–405.

Lobel M, Dunkel-Schetter C, Scrimshaw SCM. Prenatal maternal stress and prematurity: a prospective study of socioeconomically disadvantaged women. Health Psychol. 1992;11:32–40.

Norbeck J, Anderson N. Life stress, social support, and anxiety in mid- and late-pregnancy among low income women. Research in nursing & health. 1989;12:281–7.

Christian LM. Psychoneuroimmunology in pregnancy: immune pathways linking stress with maternal health, adverse birth outcomes, and fetal development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(1):350–61.

Acevedo-Garcia D, Rosenfeld LE, Hardy E, McArdle N, Osypuk TL. Future directions in research on institutional and interpersonal discrimination and children’s health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1754–63.

Giurgescu C, McFarlin BL, Lomax J, Craddock C, Albrecht A. Racial discrimination and the Black‐White gap in adverse birth outcomes: a review. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2011;56(4):362–70.

Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(1):14–24.

Dole N, Savitz DA, Siega-Riz AM, Hertz-Picciotto I, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Psychosocial factors and preterm birth among African American and White women in central North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1358–65.

Mustillo S, Krieger N, Gunderson EP, Sidney S, McCreath H, Kiefe CI. Self-reported experiences of racial discrimination and Black-White differences in preterm and low-birthweight deliveries: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2125–31.

Rankin KM, David RJ, Collins Jr JW. African American women’s exposure to interpersonal racial discrimination in public settings and preterm birth: the effect of coping behaviors. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(3):370.

• Slaughter-Acey JC, Sealy-Jefferson S, Helmkamp L, Caldwell CH, Osypuk TL, Platt RW, et al. Racism in the form of micro aggressions and the risk of preterm birth among Black women. Ann Epidemiol. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.10.005. This paper examined multiple dimensions of racism in the context of social and psychosocial factors. The results suggested that research on the intersection of racism and psychosocial factors such as depressive symptomology may provide additional insight into the complex and persistent racial disparities in birth outcomes

Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–8.

Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism‐related stress: implications for the well‐being of people of color. Am J Orthop. 2000;70(1):42–57.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status and health: complexities, ongoing challenges and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x.

Pierce C. Stress analogs of racism and sexism: terrorism, torture, and disaster. In: Willie C, Reiker P, Kramer B, Brown B, editors. Mental health, racism, and sexism. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press; 1995. p. 277–93.

Slaughter-Acey JC, Caldwell CH, Misra DP. The influence of personal and group racism on entry into prenatal care among-African American women. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(6):e381–e7.

Dominguez TP, Dunkel-Schetter C, Glynn LM, Hobel C, Sandman CA. Racial differences in birth outcomes: the role of general, pregnancy, and racism stress. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):194.

Shah N, Bracken M. A systematic review and meta analysis of prospective studies on the association between maternal cigarette smoking and preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(2):465–72.

Kahn RS, Certain L, Whitaker RC. A reexamination of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1801–8.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: summary of national findings. In: SAMSHA, editor. Rockville, MD 2014.

Schempf AH, Strobino DM. Illicit drug use and adverse birth outcomes: is it drugs or context? J Urban Health. 2008;85(6):858–73. doi:10.1007/s11524-008-9315-6.

Savitz DA, Murnane P. Behavioral influences on preterm birth: a review. Epidemiology. 2010;21(3):291–9. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d3ca63.

An R. Prevalence and trends of adult obesity in the US, 1999–2012. ISRN Obes. 2014;2014:185132. doi:10.1155/2014/185132.

Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Ananth CV. Trends in spontaneous and indicated preterm delivery among singleton gestations in the United States, 2005–2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1069–74. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000546.

Cnattingius S, Villamor E, Johansson S, Edstedt Bonamy AK, Persson M, Wikstrom AK, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2362–70. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.6295.

Salihu H, Mbah AK, Alio AP, Kornosky JL, Whiteman VE, Belogolovkin V, et al. Nulliparity and preterm birth in the era of obesity epidemic. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(12):1444–50. doi:10.3109/14767051003678044.

Khatibi A, Brantsaeter AL, Sengpiel V, Kacerovsky M, Magnus P, Morken NH, et al. Prepregnancy maternal body mass index and preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(3):212 e1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.002.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee opinion no. 549: obesity in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):213–7. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000425667.10377.60.

Martin J, Hamilton B, Osterman M, Curtin S, Matthews T. Births: final data for 2013. National Vital Statistics Report. 2015;64(1).

Whitt-Glover MC, Taylor WC, Heath GW, Macera CA. Self-reported physical activity among Blacks: estimates from National Surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(5):412–7. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.024.

Evenson KR, Wen F. Prevalence and correlates of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior among US pregnant women. Prev Med. 2011;53(1–2):39–43. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.04.014.

Barakat R, Pelaez M, Montejo R, Refoyo I, Coteron J. Exercise throughout pregnancy does not cause preterm delivery: a randomized, controlled trial. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(5):1012–7. doi:10.1123/jpah.2012-0344.

Currie LM, Woolcott CG, Fell DB, Armson BA, Dodds L. The association between physical activity and maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective cohort. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(8):1823–30. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1426-3.

Tinloy J, Chuang CH, Zhu J, Pauli J, Kraschnewski JL, Kjerulff KH. Exercise during pregnancy and risk of late preterm birth, cesarean delivery, and hospitalizations. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(1):e99–e104. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2013.11.003.

Owe KM, Nystad W, Skjaerven R, Stigum H, BØ K. Exercise during pregnancy and the gestational age distribution: a cohort study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(6):1067–74. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182442fc9.

Vamos CA, Flory S, Sun H, DeBate R, Bleck J, Thompson E, et al. Do physical activity patterns across the life course impact birth outcomes? Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(8):1775–82. doi:10.1007/s10995-015-1691-4.

Barakat R, Stirling JR, Lucia A. Does exercise training during pregnancy affect gestational age? A randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(8):674–8. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.047837.

Morgan KL, Rahman MA, Hill RA, Zhou SM, Bijlsma G, Khanom A et al. Physical activity and excess weight in pregnancy have independent and unique effects on delivery and perinatal outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4).

Jukic AMZ, Evenson KR, Daniels JL, Herring AH, Wilcox AJ, Hartmann KE. A prospective study of the association between vigorous physical activity during pregnancy and length of gestation and birthweight. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(5):1031–44. doi:10.1007/s10995-011-0831-8.

Domingues MR, Matijasevich A, Barros AJ. Physical activity and preterm birth: a literature review. Sports Med. 2009;39(11):961–75. doi:10.2165/11317900-000000000-00000.

Evenson KR, Savitz DA, Huston SL. Leisure-time physical activity among pregnant women in the US. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18(6):400–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00595.x.

Berkowitz GS, Kelsey JL, Holford TR, Berkowitz RL. Physical activity and the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. J Reprod Med. 1983;28(9):581–8.

Jukic AM, Evenson KR, Daniels JL, Herring AH, Wilcox AJ, Hartmann KE. A prospective study of the association between vigorous physical activity during pregnancy and length of gestation and birthweight. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(5):1031–44. doi:10.1007/s10995-011-0831-8.

Domingues MR, Barros AJ, Matijasevich A. Leisure time physical activity during pregnancy and preterm birth in Brazil. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;103(1):9–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.05.029.

Leiferman JA, Evenson KR. The effect of regular leisure physical activity on birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(1):59–64.

Hegaard HK, Hedegaard M, Damm P, Ottesen B, Petersson K, Henriksen TB. Leisure time physical activity is associated with a reduced risk of preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(2):180 e1–5. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.038.

Juhl M, Andersen PK, Olsen J, Madsen M, Jorgensen T, Nohr EA, et al. Physical exercise during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(7):859–66. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm364.

Nascimento SL, Surita FG, Cecatti JG. Physical exercise during pregnancy: a systematic review. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2012;24(6):387–94. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e328359f131.

Misra DP, Strobino DM, Stashinko EE, Nagey DA, Nanda J. Effects of physical activity on preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(7):628–35.

Orr ST, James SA, Garry J, Newton E. Exercise participation before and during pregnancy among low-income, urban, Black women: the Baltimore preterm birth study. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(4):909–13.

Sealy-Jefferson S Hegner K Helmkamp L Straughen J Misra De-. Linking non-traditional physical activity and preterm delivery in urban African American women. Women’s Health Issues. 2014 24(4) e389–9.

Lu M, Halfon N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: a life-course perspective. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7:13–30.

Misra D. Addressing racial disparities in perinatal health: application of a multiple determinants perinatal framework with a lifespan approach. Harvard Health Policy Review. 2006;7:72–90.

Misra D, Guyer B, Allston A. Integrated perinatal health framework: a multiple determinants model with a lifespan approach. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:65–75.

Anderson JE, Ebrahim S, Floyd L, Atrash H. Prevalence of risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes during pregnancy and the preconception period—United States, 2002–2004. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(1):101–6.

Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception. 2009;79(3):194–8.

Misra D, Astone N, Johnson C. Effect of maternal smoking on birth weight modified by parity and grandmaternal smoking: a three way interaction. Epidemiology. 2005;16:288–93.

Magnus P, Bakketeigh L, Skjaerven R. Correlations of birth weight and gestational age across generations. Ann Hum Biol. 1993;20:231–8.

Klebanoff M, Meirik O, Berendes H. Second-generation consequences of small-for-dates birth. Pediatrics. 1989;84:343–7.

Klebanoff M, Yip R. Influence of maternal birth weight on rate of fetal growth and duration of gestation. J Pediatr. 1987;111:287–92.

Klebanoff M, Graubard B, Kessel S, Berendes H. Low birth weight across generations. JAMA. 1984;252:2423–7.

Hackman E, Emanuel I, van Belle G, Daling J. Maternal birth weight and subsequent pregnancy outcomes. JAMA. 1983;250:2016–9.

Emanuel I, Filakti H, Alberman E, Evans S. Intergenerational studies of human birthweight from the 1958 birth cohort. II. Do parents who were twins have babies as heavy as those born to singletons? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:836–40.

Emanuel I, Filakti H, Alberman E, Evans S. Intergenerational studies of human birthweight from the 1958 birth cohort. I. Evidence for a multigenerational effect. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:67–74.

Conley D, Bennett N. Is biology destiny? Birth weight and life chances. Am Sociol Rev. 2000;65:458–67.

Alberman E, Emanuel I, Filakti H, Evans S. The contrasting effects of parental birthweight and gestational age on the birthweight of offspring. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1992;6:134–44.

Slaughter-Acey JC, Holzman C, Calloway D, Tian Y. Movin’ on up: socioeconomic mobility and the risk of delivering a small-for-gestational age infant. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(3):613–22. doi:10.1007/s10995-015-1860-5.

Collins J, Rankin K, David R. Downward economic mobility and preterm birth: an exploratory study of Chicago-born upper class White mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(7):1601–7. doi:10.1007/s10995-015-1670-9.

Collins Jr JW, David RJ, Simon DM, Prachand NG. Preterm birth among African American and White women with a lifelong residence in high-income Chicago neighborhoods: an exploratory study. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(1):113.

Collins Jr JW, Rankin KM, David RJ. African American women’s lifetime upward economic mobility and preterm birth: the effect of fetal programming. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):714–9.

Love C, David RJ, Rankin KM, Collins JW. Exploring weathering: effects of lifelong economic environment and maternal age on low birth weight, small for gestational age, and preterm birth in African-American and White women. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(2):127–34.

Colen CG. Addressing racial disparities in health using life course perspectives. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 2011;8(01):79–94.

Colen CG, Geronimus AT, Bound J, James SA. Maternal upward socioeconomic mobility and black-white disparities in infant birthweight. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(11):2032–9.

Gavin AR, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Maas C. The role of maternal early-life and later-life risk factors on offspring low birth weight: findings from a three-generational study. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(2):166–71.

Chapman DA, Gray G. Developing a maternally linked birth dataset to study the generational recurrence of low birthweight in Virginia. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(2):488–96.

Collins JW, Rankin KM, David RJ. Low birth weight across generations: the effect of economic environment. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(4):438–45.

Lu MC, Halfon N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: a life-course perspective. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(1):13–30.

Halfon N, Larson K, Lu M, Tullis E, Russ S. Lifecourse health development: past, present and future. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(2):344–65. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1346-2.

Lu MC. Improving maternal and child health across the life course: where do we go from here? Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(2):339–43. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1400-0.

Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Hogan V, Jones L, Wright K, Halfon N. Closing the Black-White gap in birth outcomes: a life-course approach. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(1 Suppl 2):S2. -62-76

Misra DP, Astone N, Lynch CD. Maternal smoking and birth weight: interaction with parity and mother’s own in utero exposure to smoking. Epidemiology. 2005;16(3):288–93.

Astone NM, Misra D, Lynch C. The effect of maternal socio‐economic status throughout the lifespan on infant birthweight. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21(4):310–8.

• Collins Jr JW, Rankin KM, David RJ. Paternal lifelong socioeconomic position and low birth weight rates: relevance to the African-American women’s birth outcome disadvantage. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(8):1759–66. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-1981-5. This paper used an innovative appoach with vital statistics data to study how paternal lifelong socioeconomic position relates to low birth weight (<2500 grams) by race and to racial disparity

Metcalfe A, Lail P, Ghali WA, Sauve RS. The association between neighbourhoods and adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of multi-level studies. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011;25(3):236–45. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01192.x.

Masho SW, Munn MS, Archer PW. Multilevel factors influencing preterm birth in an urban setting. Urban, planning and transport research. 2014;2(1):36–48.

Miranda ML, Messer LC, Kroeger GL. Associations between the quality of the residential built environment and pregnancy outcomes among women in North Carolina. 2012.

O’Campo P, Burke JG, Culhane J, Elo IT, Eyster J, Holzman C, et al. Neighborhood deprivation and preterm birth among non-Hispanic Black and White women in eight geographic areas in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(2):155–63.

Vinikoor-Imler L, Messer L, Evenson K, Laraia B. Neighborhood conditions are associated with maternal health behaviors and pregnancy outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(9):1302–11.

Ma X, Liu J, Hardin JW, Zhao G, Liese AD. Neighborhood food access and birth outcomes in South Carolina. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(1):187–95.

Masi CM, Hawkley LC, Piotrowski ZH, Pickett KE. Neighborhood economic disadvantage, violent crime, group density, and pregnancy outcomes in a diverse, urban population. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(12):2440–57.

Wallace M, Harville E, Theall K, Webber L, Chen W, Berenson G. Neighborhood poverty, allostatic load, and birth outcomes in African American and White women: findings from the Bogalusa heart study. Health & place. 2013;24:260–6.

David R, Rankin K, Lee K, Prachand N, Love C, Collins Jr J. The Illinois transgenerational birth file: life-course analysis of birth outcomes using vital records and census data over decades. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(1):121–32.

Kramer MR, Dunlop AL, Hogue CJ. Measuring women’s cumulative neighborhood deprivation exposure using longitudinally linked vital records: a method for life course MCH research. Matern Child Health J. 2013:1–10.

Schoendorf KC, Branum AM. The use of United States vital statistics in perinatal and obstetric research. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(4):911–5.

• Margerison-Zilko C, Cubbin C, Jun J, Marchi K, Fingar K, Braveman P. Beyond the cross-sectional: neighborhood poverty histories and preterm birth. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1174–80. doi:10.2105/ajph.2014.302441. Longitudinal poverty trajectories were derived from California data to separate the associations between cross sectional measures of poverty and longitudinal poverty measures.

Farley R, Danziger S, Holzer HJ. Detroit divided. Russell Sage Foundation; 2000.

Nyden PW, Edlynn E, Davis J. The differential impact of gentrification on communities in Chicago. Loyola University Chicago Center for Urban Research and Learning Chicago, IL; 2006.

Wodtke GT. Duration and timing of exposure to neighborhood poverty and the risk of adolescent parenthood. Demography. 2013;50(5):1765–88. doi:10.1007/s13524-013-0219-z.

Chatterjee P, Chiasson VL, Bounds KR, Mitchell BM. Regulation of the anti-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 during pregnancy. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5(MAY):1-.

Schminkey DL, Groer M. Imitating a stress response: a new hypothesis about the innate immune system’s role in pregnancy. Med Hypotheses. 2014;82(6):721–9.

Corwin EJ, Pajer K, Paul S, Lowe N, Weber M, McCarthy DO. Bidirectional psychoneuroimmune interactions in the early postpartum period influence risk of postpartum depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;49:86–93. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2015.04.012.

Giurgescu C, Engeland CG, Zenk SN, Kavanaugh K. Stress, inflammation and preterm birth in African American women. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2013;13(4):171–7. doi:10.1053/j.nainr.2013.09.004.

Benfield RD, Newton ER, Tanner CJ, Heitkemper MM. Cortisol as a biomarker of stress in term human labor: physiological and methodological issues. Biological Research for Nursing. 2014;16(1):64–71. doi:10.1177/1099800412471580.

Coussons-Read ME, Okun ML, Schmitt MP, Giese S. Prenatal stress alters cytokine levels in a manner that may endanger human pregnancy. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(4):625–31.

Coussons-Read ME, Okun ML, Nettles CD. Psychosocial stress increases inflammatory markers and alters cytokine production across pregnancy. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(3):343–50.

Coussons-Read ME, Lobel M, Carey JC, Kreither MO, D’Anna K, Argys L, et al. The occurrence of preterm delivery is linked to pregnancy-specific distress and elevated inflammatory markers across gestation. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(4):650–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.009.

Christian LM, Franco A, Glaser R, Iams JD. Depressive symptoms are associated with elevated serum proinflammatory cytokines among pregnant women. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(6):750–4. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.02.012.

Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Peters RM, Johnson DA, Templin TN. Association of depressive symptoms with inflammatory biomarkers among pregnant African-American women. J Reprod Immunol. 2012;94(2):202–9.

Fransson E, Dubicke A, Byström B, Ekman-Ordeberg G, Hjelmstedt A, Lekander M. Negative emotions and cytokines in maternal and cord serum at preterm birth. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;67(6):506–14.