Abstract

Non-Hispanic Black women remain at increased risk for adverse birth outcomes, yet Black immigrant women are at lower risk than their US-born counterparts. This study examines whether neighborhood context contributes to the nativity advantage in preterm birth (PTB, < 37 weeks) among Black women in California. A sample of live singleton births to non-Hispanic US-born (n = 83,169), African-born (n = 7151), and Caribbean-born (n = 943) Black women was drawn from 2007 to 2010 California birth records and geocoded to urban census tracts. We used 2010 American Community Survey data to measure tract-level Black immigrant density, Black racial concentration, and a neighborhood deprivation index. Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were estimated using log-binomial regression to assess whether neighborhood context partially explained nativity differences in PTB risk. Compared to US-born Black women, African-born Black women had lower PTB risk (RR = 0.65, 95%CI: 0.60–0.71). The difference in PTB risk between US- and Caribbean-born women did not reach statistical significance (RR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.71–1.05). The nativity advantage in PTB risk was robust to neighborhood social conditions and maternal factors for African-born women (RR = 0.59, 95%CI: 0.51–0.67). This study is one of few that considers area-level explanations of the nativity advantage among Black immigrants and makes a significant contribution by showing that the neighborhood context does not explain the nativity advantage in PTB among Black women in California. This could be due to many factors that should be examined in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite advancements in perinatal health care, significant racial disparities in birth outcomes remain. Non-Hispanic Black women exhibit higher preterm birth rates (PTB, < 37 weeks gestation) than non-Hispanic white women. In 2015, the PTB rate among non-Hispanic Black women was 13.4% compared to 8.9% among non-Hispanic white women.[1] However, compared to US-born Black women, Black immigrant women are at lower risk for adverse birth outcomes. For instance, in 2008, 9% of Black immigrant births were preterm compared to 12% of US-born Black births.[2] Among Black immigrants, the nativity advantage in birth outcomes varies by maternal birthplace: African-born women have better birth outcomes than Caribbean-born women, who then have better birth outcomes than US-born Black women.[2,3,4] To date, there is little consensus on the origins of the nativity advantage in Black birth outcomes. Although Black immigrant women have fewer medical and behavioral risk factors and better socioeconomic profiles, differences in these maternal factors do not entirely account for the nativity advantage in birth outcomes.[2, 5, 6]

Differences in neighborhood context may also contribute to the nativity advantage in birth outcomes. Research on neighborhood effects and nativity status in the Black population is limited, and to date, the findings are mixed. This is due in part to neighborhood context being operationalized differently, each measure capturing distinct domains of neighborhood social context. For instance, some studies find that residential segregation has a similar impact on the birth outcomes of US-born Black and Black immigrant women,[7,8,9] suggesting that similar to US-born Blacks, race remains a critical limiting factor in neighborhood options among Black immigrants.[10,11,12,13] Alternatively, studies of area-level socioeconomic conditions have shown that Black immigrant birth outcomes are not associated with area-level poverty, which may contribute to their advantage in birth outcomes.[14, 15] This parallels findings of some sociological studies, which have shown that Black immigrants maintain moderate social and spatial distances from US-born Blacks that may translate to more access to neighborhoods with better socioeconomic conditions.[12, 16].

Other studies examine the association between neighborhood racial/ethnic composition and birth outcomes by nativity status. In Minnesota, Baker and Hellerstedt found that Black racial concentration only increased PTB risk among US-born Black women.[9] In non-Black neighborhoods, Mason et al. found that increases in Hispanic density lowered PTB risk for Black immigrant women but was not associated with US-born Black PTB risk in New York City.[17] Vang and Elo reported that neighborhood minority diversity varied significantly among US-, African-, and Caribbean-born Black women in New Jersey. [18] In New York City, Mason and colleagues found that Black density and African density increased PTB risk among US-born Black and African-born Black women, respectively. However, they found no association between Caribbean-density and PTB risk among Caribbean-born Black women in New York City.[19] Interestingly, these patterns contradict the ethnic density hypothesis, which posits that residence among higher concentrations of co-ethnic peers affords immigrants more social support and resources to reduce stress and maintain overall health.[20, 21] This contradiction may be reflecting patterns of structural racism, where the benefits of residing among co-ethnics are limited by racial residential segregation that is unique to the US Black population.[22].

The studies outlined suggest that neighborhoods may contribute to nativity differences in Black birth outcomes depending on the neighborhood attribute under study. However, it is important to note that most of these studies focus on locales in the Northeast. Areas like New York City are a unique context where the Black population is much more likely to reside in predominantly Black neighborhoods, given the large concentration of the US Black population and the long history of racial residential segregation in the region.[23] For Black women, the association between birth outcomes and neighborhood conditions can differ in regions where racial segregation is less entrenched.[24] Thus, the patterns identified in New York City may not be generalizable to other locales. In Western states, where some studies have shown less Black-White segregation that is associated with higher minority socioeconomic position,[25] nativity differences in neighborhood context could be more pronounced if lower racial residential segregation levels result in more residential options and fewer instances of co-location among US- and foreign-born Blacks in highly segregated regions.

This study examines the association between neighborhood context and PTB risk among US-born, African-born, and Caribbean-born Black women residing in urban California census tracts. While nativity differences in neighborhood exposures may exist in several neighborhood domains, this study focuses on those most salient in the Black residential context. Following the ethnic enclave literature, the study examines the proportion of Black immigrant residents (Black immigrant co-ethnic density), which suggests that residence among co-ethnics increases social support and improves access to resources, especially among foreign-born. Additionally, the analysis includes measures of Black racial concentration, which offers a local neighborhood measure of systematic isolation among Black residents from other racial/ethnic groups, and neighborhood socioeconomic conditions (neighborhood deprivation) to capture the role of material disadvantage on birth outcomes. This study builds on existing literature by assessing neighborhood context’s contribution to the nativity advantage in PTB among Black women. The hypotheses were that: (1) Black immigrant co-ethnic density, Black racial concentration, and neighborhood deprivation would partially explain the nativity advantage; (2) and that the association between each neighborhood attribute and PTB risk would depend on maternal birthplace (i.e., USA, Africa, or the Caribbean).

Methods

Data Sources

This study utilized data from California birth records of all live and singleton births in California between January 2007 and December 31, 2010. The sample was restricted to births among women who self-identified as “Black only” as reported in the birth records (N = 113,360). Only successfully geocoded births (n = 105, 774, 93%) between gestational ages 22 and 44 weeks (n = 105, 189) were included in the sample.[26] The sample was limited to births to Black women (18 +) who reported their ethnicity as “Not Spanish/Latina/Hispanic” (n = 102,732) with a known country of birth (n = 98, 391) in the birth record. Women who reported their birthplace as Puerto Rico (n = 15) were treated as Hispanic and thus excluded. Births to women under the age of 18 were excluded as they accounted for less than 1% of foreign-born births (n = 26). Births to women born outside of the USA, an African country, or a non-Hispanic Caribbean country (n = 97,306) were excluded. These births were then linked to urban census tract data from the 2010 American Community Survey (ACS) using Geolytics software (Geolytics, Brunswick, NJ) (see Fig. 2 in the Appendix). After excluding births with missing neighborhood data (< 1%) and births with missing maternal information (< 6%), the final analytic sample included 91,264 births in 6340 urban census tracts. The data used for this study received approval from both the State Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (#13–06-1251) and the Institutional Review Board (HS# 2013–9716).

Preterm Birth

The outcome of interest is preterm birth, defined as a live singleton birth with a gestation of fewer than 37 weeks. Births were coded as a full-term birth if gestational age was greater than or equal to 37 weeks. Measurement of gestational age was based on obstetric estimates included in California birth records.

Neighborhood Attributes

To measure Black immigrant density, the tract-level proportion of foreign-born Blacks (per total tract population) was computed. Black immigrant density ranged from 0.02 to 18.2%, with a mean of 0.51% (SD = 1.02). Black immigrant density percentages were highly skewed; most tracts had less than 1% Black immigrants. Black racial concentration was measured as the proportion of Black residents (per total tract population) in each tract. Black racial concentration ranged from 0.4 to 87.2%, with a mean of 6.5% (SD = 9.9). Socioeconomic conditions were captured using a standardized neighborhood deprivation index developed by Messer et al. to account for multiple dimensions of material disadvantage.[27] Following the approach outlined by Messer et al., we conducted a principal component analysis to assess how each attribute (i.e., poverty, education, employment, housing, residential stability, and occupation) contributed to the sample variance. Item loading values from the first component were used to weight each attribute’s contribution to the deprivation index score.[27] Index scores were transformed into z-scores where lower z-scores represent tracts with less neighborhood deprivation, while higher z-scores represent more significant neighborhood deprivation. Neighborhood deprivation index scores in this sample ranged from − 2.4 to 5.3.

Maternal Birthplace

All analyses use maternal birthplace to assess nativity differences in preterm birth risk. Maternal birthplace is measured categorically (US-born, African-born, and Caribbean-born).

Maternal and Infant Covariates

Maternal and infant characteristics (hereafter maternal covariates) were included in all models to adjust for potential confounding in neighborhood and preterm birth risk associations. Maternal covariates included age (18–24, 25–34, 35 years or older), education (less than high school, high school graduate, greater than high school), MediCal (Medicaid) status (yes or no), parity (1 birth, 2–3 births, 4 + births), and prenatal care initiation (1st trimester vs. late/no care). Infant characteristics included infant sex (male vs. female).

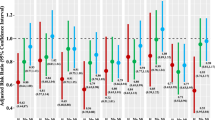

Statistical Analysis

To assess differences in neighborhood context and maternal and infant characteristics by maternal birthplace, the analyses include comparisons of maternal covariates and neighborhood attributes by maternal birthplace using Chi-square-tests and t-tests that compared African- and Caribbean-born to US-born Black women. Risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated using log-binomial regression with robust standard errors to adjust for clustering of births in census tracts. To test the first hypothesis, that Black immigrant co-ethnic density, Black racial concentration, and neighborhood deprivation partially explain nativity advantages in PTB risk, we estimated five models: model 1 estimates the crude risk of PTB for African- and Caribbean-born relative to US-born Black women. In model 2, maternal covariates were added to the previous crude model. In models 3–5, neighborhood Black immigrant concentration, Black racial concentration, and the deprivation index, respectively, were added individually to a model including maternal birthplace and covariates. To test the second hypothesis that the association between each neighborhood attribute and PTB risk depends on maternal birthplace, model 6 includes interaction terms maternal birthplace and each neighborhood attribute. Post-estimation Wald tests were used to examine the interaction terms’ overall significance and depict the predicted proportions of PTB by maternal birthplace for all neighborhood attributes (Fig. 1). All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 16.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

Table 1 compares the maternal and infant characteristics of US-born, African-born, and Caribbean-born Black women. Overall, there are significant differences in maternal and infant characteristics by maternal birthplace. Compared to US-born Black women, African-born Black women are older, have higher educational attainment, and are less likely to receive MediCal (43.5% vs. 54.4%). There were no significant differences in the proportion of male infants for US-born compared to African-born Black women. The PTB rate was significantly higher among US-born than African-born Black women (10.8% vs. 7.0%). Caribbean-born Black women are also older, more educated, and less likely to receive MediCal (36.7% vs. 54.6%) than US-born Black women. The PTB rate among Caribbean-born Black women was only marginally different from US-born Black women (10.8% vs. 9.3%). Table 2 describes the distributions of each neighborhood attribute by maternal birthplace. The results indicate some maternal birthplace differences in Black immigrant density, Black racial concentration, and neighborhood deprivation, although these differences were not large in magnitude. Compared to US-born Black women, African-born Black women resided in neighborhoods with a slightly higher Black immigrant density (1.1% vs. 0.86%), lower Black racial concentration (11.7% vs. 16.4%), and less neighborhood deprivation (− 0.45 vs. 0.03). Caribbean-born women tended to reside in neighborhoods with lower Black racial concentration (14.0% vs. 16.4%) and less neighborhood deprivation (− 0.3 vs. 0.03) than US-born Black women.

The risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals for models estimating PTB risk among African- and Caribbean-born relative to US-born Black women are presented in Table 3. Nativity status was associated with lower PTB risk among African-born relative to US-born Black women (model 1: RR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.60–0.71). PTB risk among Caribbean-born was 13% lower relative to US-born Black women; however, the results did not reach statistical significance (model 1: RR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.71–1.05). Adjusting for maternal and infant covariates did not attenuate the nativity advantage in PTB risk for African-born women (model 2: RR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.57–0.69). Adjusting for Black immigrant density (model 3), Black racial concentration (model 4), and neighborhood deprivation (model 5) did not attenuate the nativity advantage in PTB risk among African-born and Caribbean-born women. Black immigrant density (model 3; RR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.98–1.01) and Black racial concentration (model 4; RR = 1.00, 95% CI: 1.00–1.00) were not associated with PTB risk in this sample of Black women, net of maternal, and infant covariates. However, increases in neighborhood deprivation were associated with a 5% higher PTB risk net of maternal covariates (model 5; RR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.03–1.07). Model 6 includes interactions between maternal birthplace and each neighborhood attribute to assess whether the association between neighborhoods and PTB risk depends on maternal birthplace. Post-estimation Wald tests indicated significant differences in the association between PTB risk and Black immigrant density (Wald Chi-square statistic = 6.96, p < 0.05). Figure 1 shows that African-born and Caribbean PTB increased with greater Black immigrant density, while US-born Black PTB did not. There were no significant maternal birthplace interactions for Black racial concentration (Wald Chi-square statistic = 0.38, p = 0.83) or neighborhood deprivation (Wald Chi-square statistic = 3.78, p = 0.15), and adjustment for the interaction terms did not attenuate the nativity advantage in PTB risk.

Discussion

This paper examined nativity differences in preterm birth risk among non-Hispanic US-, African-, and Caribbean-born Black women living in urban California neighborhoods. There was a significant difference in preterm birth risk between US-born and African-born Black women, which was not explained by sociodemographic characteristics or health behaviors. However, the nativity difference in preterm birth risk between US- and Caribbean-born Black women did not reach statistical significance, which may stem from the limited sample of Caribbean-born Black women in this study. These findings are similar to studies that have identified nativity advantages in preterm birth and other adverse birth outcomes. [2, 8, 18, 19].

There was little support for the hypothesis that neighborhood conditions may partially explain Black nativity advantages in preterm birth risk in California. Similar to one other study on the contribution of neighborhood context to nativity advantages in Black birth outcomes in New Jersey, there was no evidence that neighborhoods partially explained the nativity advantage.[18] Related to the second hypothesis that neighborhood associations with PTB risk may differ by maternal birthplace, interaction results indicated that increases in Black immigrant density were associated with higher PTB rates among African- and Caribbean-born women, compared to US-born Black PTB rates (model 6). Similar patterns were observed in New York City, particularly in deprived urban neighborhoods.[19] Contrary to the immigrant enclave hypothesis, there was no evidence that Black immigrant density was associated with lower preterm birth risk among African- or Caribbean-born Black women. It is also important to note that Black immigrant density across all tracts was relatively low in this study, where low concentrations of foreign-born may actually reflect processes of social isolation and high concentrations of foreign-born may reflect robust and established ethnic enclaves with higher levels of social capital.[28, 29] Future studies should investigate typologies of Black immigrant neighborhoods to better contextualize their neighborhood exposures relative to settlement patterns and structural factors like residential segregation.[30].

Unlike other studies of neighborhoods and Black birth outcomes, Black racial concentration was not a significant predictor of preterm birth in this sample of Black women. As a proxy for racial residential segregation, Black racial concentration has been associated with worse birth outcomes among Black women. For instance, in both Minnesota and North Carolina, Black concentration was associated with increased preterm birth risk among Black women.[9, 31] This may indicate that Black racial concentration in California may not reflect the same mechanism to deleterious birth outcomes as the Black racial concentration in other regions.

Overall, the findings presented in this study suggest that the nativity advantage in preterm birth risk observed among foreign-born Black women is related to factors not observed in this study. For instance, the length of exposure to minority status, racism, and stress-inducing environments in the USA that leads to the accumulation of stress over Black women’s reproductive life course could also contribute to nativity differences in birth outcomes.[32, 33] Parker Dominguez et al. showed that self-reported racism was higher among US-born than foreign-born women; compared to US-born Black women, Caribbean-born women reported fewer experiences of personal racism over the life course and during pregnancy, and this difference was larger for US- and African-born women.[34] The trends described among Caribbean-born may stem from the earlier settlement of Caribbean immigrants in the USA compared to African immigrants whose migration to the USA is much more recent.[35] Longer settlement in the USA is likely capturing greater exposure to racialization and may explain why the trends in PTB nativity differences among Caribbean-born relative to US-born Black women in this study are smaller in magnitude relative to African-born Black women. Future research should examine the extent to which experiences of racism contribute to the nativity advantage in adverse birth outcomes among Black women, with particular attention to the social and physiological mechanisms that are impacted by interpersonal and structural racism.[36] Other unobserved factors that may explain the nativity advantage could stem from migrant selectivity. According to the migrant selection hypothesis, migrants are positively selected on factors related to both health and migration likelihood that result in migrants having a greater capacity to migrate relative to their home country counterparts.[37] These social and health factors may also underpin nativity advantages relative to US-born. However, additional research is needed to measure migrant selection and its contribution to the nativity advantages among Black women and their infants.

Although the study presents important contributions to the literature on the nativity advantages in birth outcomes among Black women, there are some limitations to consider. First, the findings are limited to urban census tracts in California, which may not be generalizable to rural tracts. Additionally, the data does not account for lifetime exposure to neighborhood conditions. Without measuring early-life neighborhood context, it is difficult to fully assess neighborhood context’s role in explaining the nativity advantage among Black women. Information on the length of residence in the USA in this sample is unavailable, which further limits the ability to fully capture the impact of neighborhood conditions on birth outcomes. Lastly, the data used in this analysis may not reflect current neighborhood trends in racial/ethnic concentration in California given the timing of the birth cohort used in the analysis. Despite these limitations, this study is the first to examine neighborhood conditions and the nativity advantage in Black birth outcomes in California by assessing the extent to which three salient neighborhood attributes contribute to the nativity advantage in Black preterm birth. The focus on the state of California offers an additional narrative on the birth outcomes of Black immigrants in the USA, a largely understudied subgroup.

References

Martin J, Hamilton B, Osterman M. Births: Final data for 2015. National vital statistics report. Natl Cent Heal Stat. 2017;66(1). https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/43595. Accessed March 20, 2019.

Elo IT, Vang Z, Culhane JF. Variation in Birth outcomes by mother’s country of birth among non-Hispanic black women in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(10):2371–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1477-0.

Hamilton TG, Hummer RA. Immigration and the health of U.S. black adults: does country of origin matter? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(10):1551–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.026.

Howard DL, Marshall SS, Kaufman JS, Savitz DA. Variations in low birth weight and preterm delivery among blacks in relation to ancestry and nativity: New York City, 1998–2002. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):e1399–405. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-0665.

Elo IT, Culhane JF. Variations in health and health behaviors by nativity among pregnant black women in Philadelphia. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2185. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.174755.

Almeida J, Mulready-Ward C, Bettegowda VR, Ahluwalia IB. Racial/ethnic and nativity differences in birth outcomes among mothers in New York City: the role of social ties and social support. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(1):90–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1238-5.

Margerison-Zilko C, Cubbin C, Jun J, Marchi K, Fingar K, Braveman P. Beyond the cross-sectional: neighborhood poverty histories and preterm birth. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1174–80. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302441.

Grady S, McLafferty S. Segregation, nativity, and health: reproductive health inequalities for immigrant and native-born black women in New York City. Urban Geogr. 2015;2007(28):377–97. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.28.4.377.

Baker AN, Hellerstedt WL. Residential racial concentration and birth outcomes by nativity: do neighbors matter? J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(801):172–80.

Waters MC. Black identities: West Indian Immigrant Dreams and American Realities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999.

Vang ZM. The limits of spatial assimilation for immigrants’ full integration. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2012;641(1):220–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716211432280.

Crowder K. Residential segregation of West Indians in the New York/New Jersey Metropolitan Area: the roles of race and ethnicity. Int Migr Rev. 1999;33(1):79–113. https://doi.org/10.2307/2547323.

Scopilliti M, Iceland J. Residential patterns of black immigrants and native-born blacks in the United States. Soc Sci Q. 2008;89(3):551–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2008.00547.x.

Janevic T, Stein CR, Savitz DA, Kaufman JS, Mason SM, Herring AH. Neighborhood deprivation and adverse birth outcomes among diverse ethnic groups. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:445–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.02.010.

Fang J, Madhavan S, Alderman MH. Low birth weight: race and maternal nativity–- impact of community income. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):e5–e5. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.103.1.e5.

Tesfai R. Double Minority status and neighborhoods: examining the primacy of race in black immigrants’ racial and socioeconomic segregation. City Community. 2019;18(2):509–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12384.

Mason SM, Kaufman JS, Daniels JL, Emch ME, Hogan VK, Savitz DA. Neighborhood ethnic density and preterm birth across seven ethnic groups in New York City. Heal Place. 2011;17(1):280–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.006.

Vang ZM, Elo IT. Exploring the health consequences of majority-minority neighborhoods: Minority diversity and birthweight among native-born and foreign-born blacks. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.013.

Mason SM, Kaufman JS, Emch ME, Hogan VK, Savitz DA. Ethnic density and preterm birth in African-, Caribbean-, and US-born non-Hispanic black populations in New York City. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(7):800–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq209.

Osypuk TL, Acevedo-Garcia D. Beyond individual neighborhoods: a geography of opportunity perspective for understanding racial/ethnic health disparities. Heal Place. 2010;16(6):1113–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.07.002.

Almeida J, Molnar BE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: Testing the concept of familism. Soc Sci Med. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.029.

Mehra R, Boyd LM, Ickovics JR. Racial residential segregation and adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017;191:237–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.018.

Iceland J, Sharp G, Timberlake JM. Sun Belt rising: regional population change and the decline in black residential segregation, 1970–2009. Demography. 2013;50(1):97–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0136-6.

Vinikoor LC, Kaufman JS, MacLehose RF, Laraia BA. Effects of racial density and income incongruity on pregnancy outcomes in less segregated communities. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(2):255–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.016.

Allen JP, Turner E. Black-White and Hispanic-White segregation in U.S. Counties. Prof Geogr. 2012;64(4):503–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2011.611426.

Alexander G, Himes J, Kaufman R, Mor J, Kogan M. A united states national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(2):163–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-x.

Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS, et al. The development of a standardized neighborhood deprivation index. J Urban Heal. 2006;83(6):1041–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-006-9094-x.

Becares L, Shaw R, Nazroo J, et al. Ethnic density effects on physical morbidity, mortality, and health behaviors: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):1–34. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300832.

Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Immigrant America: a portrait. 4th ed. Oakland, CA: University of California Press; 2014.

Walton E. Making sense of Asian American ethnic neighborhoods: a typology and application to health. Sociol Perspect. 2015;58(3):490–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121414568568.

Mason SM, Messer LC, Laraia BA, Mendola P. Segregation and preterm birth: the effects of neighborhood racial composition in North Carolina. Heal Place. 2009;15(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.007.

Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50068-7.

Hogue CJR, Bremner JD. Stress model for research into preterm delivery among black women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5 Suppl):S47-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.073.

Dominguez TP, Strong EF, Krieger N, Gillman MW, Rich-Edwards JW. Differences in the self-reported racism experiences of US-born and foreign-born Black pregnant women. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):258–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.022.

Kent M. Immigration and America’s Black population. Popul Bull. 2007;62(4):3–17.

Mendez DD, Hogan VK, Culhane JF. Institutional racism, neighborhood factors, stress, and preterm birth. Ethn Heal. 2014;19(5):479–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2013.846300.

Jasso G, Massey DS, Rosenzweig MR, Smith JP. Immigrant health: selectivity and acculturation. In: Anderson N, Bulatao R, Cohen B, eds. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. Washington, D.C.: The National Academic Press; 2004:227–266. https://doi.org/10.1920/wp.ifs.2004.0423

Acknowledgements

Dr. Blebu is supported by a University of California, San Francisco, Preterm Birth Initiative transdisciplinary post‐doctoral fellowship, funded by Marc and Lynne Benioff, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and a T32 training grant (1T32HD098057‐01) from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development entitled “Transdisciplinary Research Training to Reduce Disparities in Preterm Birth and Improve Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes.” I wish to thank Drs. Annie Ro and Tim A. Bruckner for access to the California data and guidance throughout this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blebu, B.E. Neighborhood Context and the Nativity Advantage in Preterm Birth among Black Women in California, USA. J Urban Health 98, 801–811 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00572-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00572-9