Abstract

Introduction

Coroners inquire into sudden, unexpected, or unnatural deaths. We have previously established 99 cases (100 deaths) in England and Wales in which medicines or part of the medication process or both were mentioned in coroners’ ‘Regulation 28 Reports to Prevent Future Deaths’ (coroners’ reports).

Objective

We wished to see what responses were made by National Health Service (NHS) organizations and others to these 99 coroners’ reports.

Methods

Where possible, we identified the party or parties to whom these reports were addressed (names were occasionally redacted). We then sought responses, either from the UK judiciary website or by making requests to the addressee directly or, for NHS and government entities, under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. Responses were analysed by theme to indicate the steps taken to prevent future deaths.

Results

We were able to analyse one or more responses to 69/99 cases from 106 organizations. We analysed 201 separate actions proposed or taken to address the 160 concerns expressed by coroners. Staff education or training was the most common form of action taken (44/201). Some organisations made changes in process (24/201) or policy (17/201), and some felt existing policies were sufficient to address some concerns (22/201).

Conclusions

Coroners’ concerns are often of national importance but are not currently shared nationally. Only a minority of responses to coroners’ reports concerning medicines are in the public domain. Processes for auditing responses and assessing their effectiveness are opaque. Few of the responses appear to provide robust and generally applicable ways to prevent future deaths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Coroners raise important concerns in attempts to prevent future deaths. |

The concerns are often directed locally, even if the responses are relevant more widely. |

Public access to the responses is often limited. |

1 Introduction

Deaths from adverse drug reactions, medication errors, and the non-medicinal use of drugs are important. Although the mortality from adverse drug reactions associated with hospital admission is low in absolute terms [1], one recent Spanish study attributed 7% of all deaths in hospital wholly or partly to medicines [2], and another suggested that as many as 18% of deaths in hospital may have been related to medicines [3]. The true figures, including deaths in the community, are not well established. Deaths from medicines are therefore a significant problem, and methods to prevent them are important if patients are to be protected.

In England and Wales, coroners investigate suspicious deaths, including deaths in custody, and make determinations of fact, which include the cause of death. Since 2009, coroners must make reports to relevant parties outlining concerns and requiring a response explaining how the concerns will be addressed. These reports are made under regulation 28 of the Coroners (Investigations) Regulations 2013 and are known as Reports to Prevent Future Deaths (henceforth referred to in the text as coroners’ reports). Coroners’ reports are published on the website of the UK judiciary [4]. Responses are required within 56 days. Some responses, but not all, are subsequently posted on the UK judiciary website. “The Chief Coroner has discretion over what is posted; and there may also be administrative delays” [4].

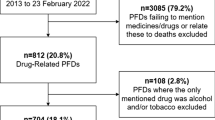

We have previously reported findings in a consecutive series of 500 coroners’ reports posted from 24 April 2015 to 7 September 2016 [5]. Of these, 99 expressed concerns about medicines or part of the medication process or both. The cases are listed in Table 1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM). Interest in these problems has increased in the last two decades: PubMed listed 176 citations under ‘medication error’ in 1997, 636 in 2007, and 1114 in 2017 [6]. We considered that fatal events were most likely to prompt action to increase medication safety. We wished to see what responses were made by NHS organizations and others to these 99 coroners’ reports.

2 Methods

We identified the addressees named in the 99 coroners’ reports from our initial study. Where the addressee’s response was posted on the UK judiciary website [4], it was downloaded for analysis. Where the response was not published and where the addressee was identifiable, we wrote to the individual or organization concerned asking for a copy; for NHS and other public organizations, this was framed in the form of a Freedom of Information (FoI) Act 2000 request. We tracked the fate of such requests and analysed responses when we successfully obtained information.

A first letter was sent in August 2017 and a follow-up letter about 3 months later. We considered all information submitted to us up to 1 February 2018, that is, approximately 6 months after the first approach. Two researchers (REF and TJA) separately categorised all responses. Disagreements were resolved by discussion; where necessary, a third researcher (ARC) mediated.

We examined the extent to which the responses appeared to address the concerns raised by the coroner. We also considered the extent to which the responses were (1) of general interest and (2) generally disseminated, since errors in healthcare are recognized to be important and lessons easily forgotten [7].

3 Results

The concerns expressed by coroners and previously set out [5] are summarized in Table 1.

Table 2 shows the organizations that received coroners’ reports for the 99 cases (100 deaths) we studied. Some organizations, such as hospitals, received more than one coroner’s report and are represented more than once. The Care Quality Commission (CQC) received eight different coroners’ reports, the most of any organization. A coroner’s report referred to a single inquest but could raise more than one matter of concern.

We identified 91 public organizations and 22 private organizations that were sent one or more coroners’ reports. The number of individual reports requiring a response are shown in Table 2. One coroner’s report omitted the name of the addressee but was accompanied by a response from a hospital trust (case 2015-0195). This was included in the figure for those required to respond and for those whose responses were posted online.

We identified 125 organizations that were sent a coroners’ report but whose responses had not been published online at the start of our study. In addition, we found that one response from the Department of Health (case 2015-0289), of the 34 responses already published, was uninformative but referred to an unpublished response from the National Medical Director of NHS England. We therefore requested information on the 126 required responses that were not in the public domain. We also requested information from a further 30 entities named in coroners’ reports but not required to respond. These entities included NHS England, the CQC, and NHS trusts that had been sent copies of reports but were not required to respond.

Table 3 summarizes the number of requests and responses, and details are provided in Table 2 in the ESM.

The responses of 44 organizations (28% cases) to coroners’ reports were posted on the UK judiciary website by the completion of the study [4]. We were able to analyse at least one response regarding 69/99 (70%) of the cases.

Coroners’ reports specify that an answer is to be returned within 56 days. There were 53 coroners’ reports that gave relevant dates. For these 53 reports, the median time for a coroner to issue a report was 240 (range 73–1027) days after the date of death. The median time it took addressee organizations to respond to the coroner’s report was 53 (range 8–311) days.

The responses we analysed described 201 separate actions proposed or undertaken. These included staff education or training (44/201), change in processes (24/201) and altered policies (17/201). In some cases (22/201), organizations felt existing policies were sufficient (Table 4).

3.1 Illustrative Cases

3.1.1 Case 2016-0096

This case concerned an interaction between warfarin and miconazole oral gel (to treat the patient’s oral thrush) that proved fatal. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issued advice to all relevant healthcare professionals; this message was reiterated by the General Dental Council. The Welsh government issued a patient safety notice to all NHS organizations and independent contractor providers in Wales. The interaction warning was added to postgraduate educational material for dentists and pharmacists in Wales.

3.1.2 Case 2016-0143

A woman with malnutrition taking paracetamol reported abdominal discomfort. Her liver function became abnormal and, despite acetylcysteine treatment, her condition deteriorated and she died. The cause of death was given as 1a. Respiratory failure, 1b. Pulmonary oedema, 1c. Severe multifactorial malnutrition, 2. Acute pyelonephritis, electrolyte imbalance, anaemia, and immune deficiency. The coroner was concerned that “the dose [of paracetamol] administered was the standard adult one” but that she weighed less than 50 kg. The trust responded by citing the British National Formulary, which gave no indication that dose adjustment was needed, and the MHRA, which had stated that body weight alone was not considered a risk for paracetamol toxicity, although malnutrition was. The trust proposed to inform its prescribers of the possible need for dose reduction.

3.1.3 Case 2015-0414

A patient with a mechanical mitral valve was advised to avoid pregnancy but fell pregnant. Termination was planned for 8 weeks’ gestation. The patient was admitted to hospital with respiratory distress. The coroner found that “the medical cause of death was multi-organ failure due to acute thrombosis of mechanical mitral valve in the first trimester of pregnancy…” and that inadequate doses of enoxaparin contributed to fatal thrombosis of the valve. The coroner expressed concern that pregnant women with mechanical valves may be at risk from insufficient antithrombotic therapy with enoxaparin and insufficient review of their anti-factor Xa activity. The coroner was also concerned that clinicians without specialist cardio-obstetric knowledge across the region failed to appreciate the risks of a mechanical heart valve in a pregnant patient. The British Cardiovascular Society received the coroner’s report and responded by organising educational material and workshops on the theme of pregnancy and mechanical heart valves for its members.

3.1.4 Case 2015-0273

An elderly care home patient with emphysema contracted bronchopneumonia. His general practitioner (GP) prescribed antibiotics, which were administered. However, his regular medication (aspirin, senna, doxycycline, and omeprazole) was not given. The coroner concluded that “death was due to bronchopneumonia as a result of emphysema, and that the omission of medicines did not cause or contribute to the patient’s death, but the risk of such an omission causing death in other circumstances [was] clear”. The care home response was to establish better communication channels with GPs in the area and obtain patient care summaries from the GP to ensure all medications are accurately managed. It has introduced medication reviews for patients and regularly updates patient care plans. The care home also reported that it now communicates with GP practices after patients are discharged from hospital to ensure any change in care or medication is implemented.

3.1.5 Case 2015-0423

The patient was discharged from hospital after a fall. He was supposed to receive 4 weeks of prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin according to hospital policy and was discharged to a care home with 4 weeks’ supply. However, documents on discharge said 3 weeks. The care home administered treatment for 3 weeks. The discrepancy between the actual supply of medication and duration in the letter was not queried, leading to sub-optimal treatment contributing to the patient’s death. The cause of death was certified as “1a. Pulmonary embolus; 1b. Deep venous thrombosis; 1c. Fractured right neck of femur; 2. Sub-optimal deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis”. The response of the care home was not published, and they did not respond to our request for information. The hospital, a second addressee, did carry out a review following the death of this patient and took action intended to reduce the risk of this type of error.

3.1.6 Cases 2015-0463 and 2016-0014

Two cases concern fentanyl patches. In the first case, a woman with severe chronic pain had been treated with fentanyl patches for 4 years. The night before she died, her uncle had applied a patch that had been inadvertently damaged when he removed it from packaging. The coroner expressed concern to the manufacturer that there were no warnings regarding the dangers of damaged patches. The manufacturer’s response was not available to us. In the second case, a woman receiving fentanyl patches as part of terminal care was told by a palliative care nurse to remove old patches by soaking in the bath; she had a hot bath and died, probably as a result of the rapid heat-induced release of remaining fentanyl from the ‘spent’ patch. The coroner expressed concerns to the palliative care organization, the general practice, and the manufacturer about these inadvertent overdoses. The manufacturer contacted the MHRA, who issued a warning of the potential dangers from the rapid release of fentanyl if patches are heated.

3.1.7 Case 2015-0229

A patient with renal disease died from codeine poisoning. The drug was prescribed at the request of a locum consultant, but neither he nor the junior doctor who wrote the prescription was aware of the relevant trust guidelines. The trust responded that it had carried out detailed investigations and found no evidence to suggest lack of knowledge or failure of locum staff. Nonetheless, the trust decided that codeine should no longer be available for routine prescription by general surgeons.

3.1.8 Case 2015-0170

A patient died as a result of post-traumatic epilepsy. He was prescribed sodium valproate but was not collecting his prescriptions. His GP saw him several times, but his medication was not discussed. The coroner raised concerns that general practice did not have any systems in place to monitor uncollected prescriptions. The general practice responded that it had updated its systems to alert doctors to outstanding prescriptions.

3.1.9 Case 2015-0377

A baby died shortly after birth following a long and complicated labour. The coroner was concerned that registrars had delayed the administration of oxytocin, indicated on clinical grounds (meconium-stained liquor and infrequent contractions at late stage of labour). The coroner also raised concerns with regard to the hospital’s incident review process, which did not inform or involve those responsible, and thereby missed the opportunity for the organization and the doctors to learn from the case. The organization responded that they had subsequently shared learning from this case via staff communications and amended their review process.

4 Discussion

Coroners expressed concerns about many medication errors and directed their reports to a wide range of institutions, including prisons, hospitals, care homes, government agencies or departments, and pharmaceutical firms. In assessing the responses to these concerns, we found fewer than one-third of responses had been published on the UK judiciary website. No clear indications were given of what process was involved in deciding whether responses were published or any indication of the timeframe in which responses would be published.

We requested from those who had received a coroner’s report any unpublished responses, using FoI legislation [8] with public bodies. “A safety culture encourages greater transparency around errors and harm, which in turn allows for open discussions to better understand what happened—and how to prevent recurrence of the event—as well as disclosure to patients” [9]. There have been long-standing calls for openness in the NHS [10], and openness in the NHS is government policy [11]. Nonetheless, many organizations, including public bodies, were slow to respond to our requests and resisted releasing information. In the case of public bodies, this was despite repeated requests under the FoI Act. This lack of transparency hampered our study and limits the potential value of coroners’ reports.

Public health physicians in Melbourne, where all responses are published, were critical of the “opacity of many response letters” [12]. Only 125 of 282 responses to coroners’ recommendations (44%) stated explicitly whether action had been taken or was intended.

We were unable to find any published appraisal process to show whether coroners had received responses to their reports and whether the actions outlined in responses were appropriate.

Despite these deficiencies in the communication of medication risks and solutions, the coroners’ reports prompted actions that would otherwise probably not have been taken. Our illustrative cases show this but also show that there may be local problems, and local solutions, that would be more useful if they were disseminated more widely. In some cases, national bodies addressed directly (cases 2016-0096, 2015-0414) or advised by others (case 2016-0014) issued warnings. In other cases, local solutions were proposed to problems of communication (case 2015-0273), monitoring (2015-0170), and timeliness of drug administration (2015-0377) that would have been of national relevance (Table 5). Sometimes, as when codeine was banned from surgical wards to prevent prescription of the drug to patients with renal impairment (case 2015-0229), proposed solutions failed to tackle the underlying general problem that drugs are sometimes prescribed to patients in whom they are contraindicated.

There have been several high-profile examples of the tardy recognition of unsafe practice in the NHS preventing lessons from being learnt quickly and so putting further lives at risk. The independent report into deaths at the Gosport War Memorial Hospital found that poor prescribing and use of opiates led to a substantial number of premature patient deaths [13]. The inquiry found that the coroner had not reported under ‘Rule 43 of the Coroners Rules 1984: action to prevent the recurrence of similar deaths,’ which preceded regulation 28 of the Coroners (Investigations) Regulations 2013 and Reports to Prevent Future Deaths. Concerns about issuing such reports arise from the perception they are punitive in nature. Coroners’ reports may be more likely to contribute towards patient safety if they are directed to the relevant national organizations as well as to local addressees but only if they are seen as an effort to achieve improvement. It is therefore important that concerns in such reports are framed constructively and are overtly conducive to patient safety.

In other jurisdictions, coroners can make direct recommendations rather than simply express concerns and invite recommendations [14].

For example, “In New Zealand coroners have a duty to identify any lessons learned from the deaths referred to them that might help prevent such deaths in the future” [15]. For closed cases, these recommendations are published online in a searchable database [16]. A study in New Zealand retrospectively reviewed 1644 recommendations sent to one or more of 309 recipients regarding 607 coronial enquiries [17]. Of the 607 inquests, deaths caused by exposure to or poisoning by noxious substances accounted for 42, and complications of medical and surgical care for 58. Many recommendations were addressed to the Ministry of Health or “all District Health Boards”, and very few were sent to individuals.

An Australian study reviewed 30 medication-related deaths in residential care for the elderly. The authors identified the cases from the Australian National Coronial Information System over 14 years [18]. The medicines most often implicated were opioids and psychiatric medicines, alone or together. In four cases, medicines were administered to the wrong patient. Coroners made recommendations, for example, regarding education and training. However, they did so in just three cases.

It is not currently possible to tell whether coroners’ reports save lives. Coroners are responsible for inquiring into all manner of deaths, of which deaths related to healthcare are only a part. Nor is it the place of healthcare professionals to suggest to coroners how they should operate. From the perspective of the NHS, and healthcare generally, the concerns that coroners express often bring systems failures and errors of general importance into the open. If coroners’ reports were routinely addressed to the relevant national body (for example, NHS Improvement, the CQC, or the MHRA), that would allow higher-level regulatory expertise to assess and act on any system-wide issues identified. Important information to prevent future deaths would be available to the whole NHS and lessons less easily forgotten.

5 Conclusion

Medicines feature in a substantial number of coroners’ reports to prevent future deaths. The concerns expressed in the reports vary widely. The coroners’ reports are often addressed locally when they are of national importance, in contrast to other places such as New Zealand, where most reports are widely disseminated. In spite of pleas for openness and recognition of lessons from error improving patient safety, responses are often unpublished, and many organisations are reluctant to share their responses. There appears to be no system for auditing concerns and responses to them. So, it is difficult to know whether—with regards to medicines—the coronial system prevents future death. Only a minority of the responses that we analysed appear to provide robust and generally applicable ways to prevent future deaths.

References

Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329:15–9.

Montané E, Arellano AL, Sanz Y, Roca J, Farré M. Drug-related deaths in hospital inpatients: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018 Mar;84(3):542–52.

Pardo Cabello AJ, Del Pozo Gavilán E, Gómez Jiménez FJ, Mota Rodríguez C, de Luna Del Castillo J, Puche Cañas E. Drug-related mortality among inpatients: a retrospective observational study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(6):731–6.

United Kingdom Courts and Tribunals Judiciary. https://www.judiciary.uk/related-offices-and-bodies/office-chief-coroner/pfd-reports/. Accessed 29 Aug 2018.

Ferner RE, Easton C, Cox AR. Deaths from medicines: a systematic analysis of coroners’ reports to prevent future deaths. Drug Saf. 2018;41(1):103–10.

Anonymous. Pubmed Time-line. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=medication+error. Accessed 03 Sep 2018.

Donaldson L. An organisation with a memory. Clin Med (Lond). 2002;2(5):452–7.

Anonymous. What is the Freedom of Information Act? Information Commissioner’s Office. https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-freedom-of-information/what-is-the-foi-act/. Accessed 10 July 2018.

Gandhi TK, Berwick DM, Shojania KG. Patient safety at the crossroads. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1829–30.

Berwick DM, Enthoven A, Bunker JP. Quality management in the NHS: the doctor’s role. BMJ. 1992;304(6821):235–9.

Hunt J. NHS: learning from mistakes, 9th March 2016. Hansard 2016;607(Column 295). http://bit.ly/2NBxFOq. Accessed 3 Sep 2018.

Sutherland G, Kemp C, Studdert DM. Mandatory responses to public health and safety recommendations issued by coroners. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2016;40:451–60.

Gosport Independent Panel. The inquests, chapter 8. In: Gosport War Memorial Hospital. The Report of the Gosport Independent Panel. https://www.gosportpanel.independent.gov.uk. Accessed 8 July 2018.

Coroners Court of Victoria. State government of Victoria. Death investigation process; 2017. http://www.coronerscourt.vic.gov.au/resources/1e321087-60c8-4c56-beb3-63d29d263c81/coronial+processes.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2018

Introduction to Recommendations recap. A summary of coronial recommendations and comments made between 1 July 2017 and 31 December 2017. https://coronialservices.justice.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/issue-14-recommendations-recap2.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2018.

Coronial Services of New Zealand. Findings and recommendations. https://coronialservices.justice.govt.nz/findings-and-recommendations/. Accessed 29 Aug 2018.

Moore J. Coroners’ recommendations about healthcare-related deaths as a potential tool for improving patient safety and quality of care. New Zealand Med J 2014;127 (1398). http://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/read-the-journal/all-issues/2010-2019/2014/vol-127-no.-1398/6212. Accessed 03 Sep 2018.

Jokanovic N, Ferrah N, Lovell JJ, et al. A review of coronial investigations into medication-related deaths in Australian residential aged care. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.06.007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The West Midlands Centre for Adverse Drug Reactions receives funding from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

Conflict of interest

Robin Ferner has provided medicolegal reports for coroners and others. Tohfa Ahmad, Zainab Babatunde and Anthony R. Cox have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this study.

Ethical approval

This study was an analysis of publicly available data. No approval was sought.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferner, R.E., Ahmad, T., Babatunde, Z. et al. Preventing Future Deaths from Medicines: Responses to Coroners’ Concerns in England and Wales. Drug Saf 42, 445–451 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-018-0738-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-018-0738-z