Abstract

Purpose of Review

The purpose of this review was to examine the knowledge, attitudes and behaviours (KAB) related to dietary salt intake among adults in high-income countries.

Recent Findings

Overall (n = 24 studies across 12 countries), KAB related to dietary salt intake are low. While consumers are aware of the health implications of a high salt intake, fundamental knowledge regarding recommended dietary intake, primary food sources, and the relationship between salt and sodium is lacking. Salt added during cooking was more common than adding salt to food at the table. Many participants were confused by nutrition information panels, but food purchasing behaviours were positively influenced by front of package labelling.

Summary

Greater emphasis of individual KAB is required from future sodium reduction programmes with specific initiatives focusing on consumer education and awareness raising. By doing so, consumers will be adequately informed and empowered to make healthier food choices and reduce individual sodium intake.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of mortality and morbidity, with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) accounting for 17 million (48% of NCD deaths) [1]. Dietary sodium intake is a key determinant for increased blood pressure (BP) and CVD risk, and evidence suggests excess intake is associated with kidney disease and stomach cancers [2,3,4]. For the prevention of disease, the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that daily sodium intake should not exceed 2 g per day (the equivalent of 5 g of salt) [5]. However, most adults consume more than 10 g per day, almost double the recommended maximum intake [6].

Mortality related to NCDs is projected to increase 15% by 2020 to 44 million deaths [1]. Given the determinants for NCDs are largely modifiable, public health action is a priority. In 2013, the WHO and Member States made a global commitment to reduce population sodium intake by a relative 30% by 2025, with the aim of reducing premature mortality by 25% [7]. Since then, over 41 high-income countries globally have created national sodium reduction strategies [7, 8••, 9••, 10]. In the UK, the national salt reduction programme resulted in a 30–45% reduction in the sodium content of foods available to purchase in supermarkets since implementation in 2003 [11].

Because approximately 75% of dietary sodium in high-income countries comes from processed foods [8••, 12], sodium reduction initiatives have focused on the food industry reducing the sodium content of processed foods, voluntary and statutory regulations on nutrition information and front-of-package labelling, and taxation of foods high in sodium [4, 8••, 9••, 13, 14]. However, salt added at the table or during food preparation (discretionary salt) (~ 15% of dietary salt) is also important, and [8••, 12] reducing the global burden of disease requires action across all levels, from individual choice to policy [8••, 15]. Therefore, many sodium reduction programmes have taken a multifaceted approach combining the food industry interventions mentioned above with consumer awareness campaigns to promote individual level behaviour change [8••, 9••, 15].

Behaviour change is complex, and understanding the knowledge, attitudes and behaviours (KAB) related to dietary salt use is key [8••, 12]. Nutrition knowledge and attitudes together can influence consumers to change dietary behaviours [16, 17]. Measures for knowledge may be defined as declarative (the awareness of things and processes, i.e. ‘what is’), and procedural (the awareness of how to do things), with attitudes/beliefs being defined as the perceived link between two concepts [17]. Research assessing KAB related to dietary salt have measured consumers knowledge of dietary recommendations, food sources and diet-disease relationships; attitudes towards salt reduction, health concerns and individual intake; and behaviours related to salt use during cooking and at the table and food purchasing choices [8••, 18].

Assessing the KAB of a population is important to inform the direction of salt reduction programmes and awareness campaigns [8••]. Measures taken at baseline, prior to the implementation of a programme also provide the opportunity to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of an intervention. Our aim was to conduct a systematic review of the literature to assess the knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to dietary salt intake of adults in high-income countries.

Methods

This systematic review was based on the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration [19].

The following were the outcomes of interest for this review:

-

1.

Knowledge related to dietary salt intake

-

2.

Attitudes related to dietary salt intake

-

3.

Behaviours related to dietary salt intake

-

4.

Parental knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to dietary salt intake of children (under 18 years of age)

Inclusion Criteria

Studies included in this review met the following inclusion criteria: (1) published in English, (2) published between January 1950 and June 2018 inclusive, (3) reported quantitative data on at least one outcome of interest (as listed above), and (4) completed in a high income country as defined by the World Bank [20]. The following study designs were included: cross-sectional, longitudinal, and where available baseline data were provided, intervention studies. Included participants were healthy, adult participants (aged 18 years and older) of all backgrounds.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies where participants were recruited from foodservice/industry or hospital settings, or had been diagnosed with a chronic disease were excluded because of their likelihood of having greater knowledge, awareness and positive behaviours related to dietary sodium intake.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was carried out across the following four scientific databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL-Plus, Scopus and Google Scholar using the keywords: knowledge, awareness, perception, attitude, perspective, belief, behaviour, habit, practice, dietary salt, dietary sodium, discretionary salt, dietary intake and consumption. The initial search strategy for MEDLINE (Supplementary Information) was developed in consultation with a university subject librarian and amended as appropriate for the other databases.

Selection of Studies

Initial search results from electronic databases were exported to Mendeley reference management system for review by the first author. After removing duplicates, studies were screened for potential inclusion based on titles and abstracts. Where eligibility was uncertain, full texts were sought and reviewed. The second and third authors were consulted where further judgement regarding eligibility was required.

Data Extraction

Data extraction for included studies was completed by the first author and overseen by the second and third authors. The following information was extracted using a data collection form which was first piloted on a small selection of studies and revised accordingly: author, year, country, aim, study design, recruitment method, sample characteristics (sample size, proportion of female respondent’s age range) and outcomes.

Results

Description of Included Studies

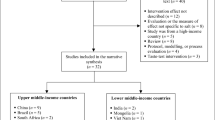

Of the 736 studies identified by initial search results, 203 were duplicates, and the remaining 533 were screened using titles and abstracts (Fig. 1). Of these, 486 were excluded based on their title and abstract and full texts of the remaining 47 studies were then reviewed. Twenty-one further papers were excluded because: KAB were not reported as outcomes of the review (n = 12), participants were recruited from the foodservice industry (n = 2), the manuscript reported an intervention study with no suitable baseline data (n = 3), and only qualitative outcomes were reported (n = 4). Twenty-four unique studies from 26 papers met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review, as summarised in Fig. 1.

Table 1 provides a summary of the 24 studies included in the review. Studies were conducted between 2001 and 2018 across 12 countries: eight from Australia [22, 25,26,27,28, 32, 41, 43], seven from the USA [24, 30, 33, 36, 38, 44, 45], two from Canada [21, 37], and one each from the Baltics [39], Barbados [29], Croatia [42], Greece [34], Ireland [40], New Zealand [46], South America [23], South Korea [31] and the UK [35]. All studies used a cross-sectional design. Participant recruitment methods included use of internet consumer panels (n = 10), random sampling via telephone listings (n = 4), electoral rolls (n = 1), door-to-door recruitment (n = 1), or national survey/population registers (n = 2), and convenience sampling via snowballing (n = 1), email advertisements (n = 1), mail consumer panel (n = 1), shopping centres (n = 2). One study [27] used multiple recruitment methods including an Internet consumer panel, social media advertising and convenience sampling at shopping centres. Study sample sizes ranged from 76 to 7845 and participants were aged 18 to over 65 years. In all studies, more than 50% of respondents were female (range 51–100%).

Studies used various measures for measuring KAB. Questions included were developed in consultation with experts in the field or adapted from other previously administered national health surveys such as the World Health Organisation/Pan American Health Organisation (WHO/PAHO) questionnaire on knowledge, attitudes and behaviour related to dietary salt intake, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Systems (NHANES), the Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, Australian Division of World Action on Salt and Health (AWASH) and Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH). Only one Australian study [41] reported using a validated questionnaire [18] to assess knowledge related to dietary sodium intake.

Seventeen studies reported on all three concepts, i.e. knowledge, attitudes and behaviours, four reported on knowledge and behaviours, three on knowledge and attitudes, one on attitudes only, and one on parental KAB. To assess KAB related to dietary salt intake, studies reported on outcomes in three ways: (1) by prevalence in the total study population (n = 18; summarised in Table 2); (2) by difference in prevalence between sub-groups based on sociodemographic and health characteristics (n = 12); and (3) associations between knowledge and attitudes on salt-specific behaviours (n = 2).

Knowledge Related to Dietary Salt Intake

Declarative Knowledge

Fifteen studies assessed participants’ knowledge of the recommended maximum daily intake for sodium [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29, 31, 34, 40, 43, 45, 46]. The proportion of participants who were able to correctly identify the recommended dietary intake for adults ranged from 4 to 54% (Table 1). Comparisons made between those who believed they were consuming the correct amount of sodium found they were in-fact consuming higher than the recommended intake of 2000 mg/day [29]. Those who believed the maximum daily intake recommendation was higher than the actual value were more likely to be consuming above or about the maximum amount [46].

The relationship between salt and sodium was also not well understood. This concept was assessed in seven studies [23, 25,26,27,28, 34, 35, 40, 46] across which, 56–89% were unable to identify the correct relationship, i.e. that salt contains sodium and that they are not the same. Sub-group analysis showed older participants [27, 34] and females [27] were less likely to understand the relationship between salt and sodium.

Sixteen studies reported on the relationship between excess sodium intake and NCDs [22,23,24,25, 27, 29,30,31,32, 34, 35, 39, 43,44,45,46]; specifically, participants were aware of the association between excess sodium intake and hypertension (79–97%) [22, 25, 27, 29, 32, 34, 35, 43, 44, 46], heart attack (12–88%) [22, 27, 43, 46] and stroke (72–77%) [22, 30, 43, 46]. Less well known was the associated risk between dietary salt and kidney disease (16–68%) [29, 43, 46], stomach cancer (8–26%) [29, 46] and osteoporosis (8–31%) [29, 35, 46]. However, one South Korean study [31] reported participants were highly aware of the relationship between sodium intake kidney disease (99%) and stomach cancer (98%). Increasing level of education, income and older age were positively associated with diet-disease knowledge [39, 41].

More than half of respondents in eight different studies measuring food sources of salt were able to correctly identify the primary source of dietary salt as processed/pre-packaged foods [22, 27, 37, 38, 40, 42, 44, 46]. In Canada, 90% of participants knew processed foods contributed the most salt to dietary intakes, though 50% were unable to recognise high-sodium foods such as processed cheese, hamburgers, canned vegetables or vegetable juice, bottle sauces and salad dressings as contributing food items [37].

Procedural Knowledge

Three studies presented participants with a series of nutrition information panels (NIPs) to assess procedural knowledge [24, 26, 33]. Forty-two percent of participants were able to successfully rank foods from high to low sodium content [26]. Twenty-one percent were able to identify foods with high sodium content [24], and 56% reported being able to monitor their sodium intake based on the information provided on food packages [33].

Attitudes Related to Dietary Salt Intake

Attitudes of adults related to dietary salt intake were reported in 20 studies. Indicators assessed participants’ concerns about sodium intake and health, taste preferences for salty foods, self-efficacy, willingness and perceived barriers to reducing salt intake, perceived responsibility for reducing population sodium intake, and agreement/disagreement with various food labelling and salt reduction initiatives.

Participants were generally concerned about the amount of salt in foods (44–89%) [21, 23, 25,26,27,28, 34, 37], and a high proportion (42–87%) agreed it was important to reduce the amount of salt in their diet [21, 32, 33, 37, 42]. Participants reported that they would be willing to use low salt/salt-free seasonings, reduce cooking with salt and reduce salty snacks [29, 46]. Reasons for reducing salt intake related to health concerns, wanting to improve overall health and recommendations by health professionals [21, 38, 45, 46]. Males, younger participants and higher socioeconomic participants were more likely to agree their health would improve by reducing dietary salt intake [27].

Taste preferences were reported in two studies [28, 35]; 31–39% agreed salt added to food makes it taste better. Misconceptions about salt, such as the belief that speciality salts (Himalayan salts, pink salt, etc.) were healthier than regular table salt (37%) [27] were more likely to translate to discretionary salt use [41].

Across six studies which asked participants who they believed was responsible for reducing population sodium intake, high levels of agreement were found for individuals being the most responsible (89%) [22, 27, 28, 45], followed by food industry (26–81%) [21, 22, 27, 36, 45], fast food chains (77%) and chefs (76%) [28, 36, 37, 45]. While less responsibility was specifically placed on government [22, 40], there was support for initiatives to reduce sodium through broad-based policies in school and workplace cafeterias, education interventions and salt taxes from participants in the USA [36, 45], Australia [27, 28] and Ireland [40]. Females, older participants, and those from higher socioeconomic groups were more likely to agree laws should be in place for limiting the amount of salt added to processed foods [27, 28, 45].

Participants reported confusion about how to read food labels to determine the amount of salt/sodium in a food product and how much sodium they should be consuming from these foods [32, 33] and suggested preference for food labels to contain information about salt and sodium, display nutrition information per serving rather than per 100 g/ml [34], and provide indicators for low, medium and high salt content [23]. At least 75% believed ‘reduced salt’ and ‘low salt’ claims would positively influence purchasing intent [30, 31].

Behaviours Related to Dietary Salt Intake

Behaviours related to dietary salt intake of adults were reported in almost all studies (n = 22). Indicators for behaviour included discretionary salt use, reported actions to reduce salt intake, and food purchasing behaviours. Discretionary salt use was reported by seven studies. Salt use at the table was less common (< 30%) [21, 25, 34] than salt added to food during preparation/cooking (24–80%) [21, 25, 29, 34, 39, 41, 44]. Older participants were less likely to report discretionary salt use [25, 39, 41].

The proportion of participants who reported to be actively reducing dietary salt ranged from 40 to 65% across eight studies [21, 23,24,25, 32, 38, 45, 46]. Those who believed sodium reduction was important were more likely to report taking action to reduce their salt intake [38]. Strategies to reduce intake included avoiding processed foods (> 44%), using low salt alternatives (34%), use of herbs and spices other than salt (29%), limiting amount of salt used, and requesting low salt alternatives when eating out (45%) [29, 32, 34, 38, 39, 46].

Nutrition information panels and other labelling on food packages were important to food purchasing behaviours as reported in 12 studies. Although < 60% of participants reported checking food labels while shopping [21, 23, 25, 30, 33, 34, 37, 38, 43, 45,46,47], the Australasian Heart Foundation Tick label, ‘low/reduced salt or sodium’ and ‘no salt/sodium’ food labels positively affected food purchases [21, 25, 33, 38, 43, 45, 46]. Use of food labels increased with age [25], and women were more likely to report using labels than men [33, 34].

Parental Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviours Related to Dietary Salt Intake

Only one study from Australia [28] (n = 837) specifically assessed parent/caregivers’ KAB related to dietary salt intake of children, and investigated whether reported salt-related knowledge or attitudes were related to salt-specific behaviours [28]. Parents were generally aware Australian children consume too much salt (73%) and agreed long-term excess salt intake during childhood may be harmful to children’s health (77%). Forty-six percent of parents/caregivers admitted adding salt to food prepared for children and 32% reported that their child or children added salt to their food at the table. Discretionary salt was less likely to be used where parents/caregivers held the belief that excess childhood intake may have harmful effects on children’s health, and where parents/caregivers reported it was important to them to limit the amount of salt their child or children consumed.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to assess the knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to dietary salt intake among adults in high-income countries. Twenty-four studies across 12 countries were included. Overall, included studies showed relatively low levels of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to dietary salt intake.

With respect to declarative knowledge, while most adults were aware of the association between excess salt/sodium intake and NCD risk (particularly hypertension and CVD), they were generally unaware of the dietary intake recommendations and the relationship between salt and sodium. Another finding of interest was that although participants were able to correctly identify processed foods as the leading contributor to dietary sodium, they were unable to recognise the ubiquity of sodium in the food supply, and associate foods commonly consumed on a daily basis such as bread, cereals, cheese, sauces and condiments, hamburgers as ‘processed foods’ [37, 42].

Procedural knowledge is considered more indicative of behaviours than declarative knowledge [17, 18]. Overall, participants lacked procedural knowledge to interpret NIP’s on food packages in order to identify high/low sodium content foods, or monitor their salt/sodium intake. Poor procedural knowledge could be explained by participants’ low declarative knowledge regarding dietary intake recommendations, and thus not having a standard reference with which to compare information provided on food labels. However, with regard to food purchasing behaviours, this review found that participants frequently referred to front of package labelling (FoP) on food products to make favourable purchasing decisions. Consistent with other research on food labelling, preferred food labels were those that were clear, concise and easy to understand such as ‘no salt’, ‘low salt’ or ‘reduced salt’ messages, or visual icons and ratings such as traffic lights which indicated high, medium and low sodium content [33, 48,49,50]. The recent introduction of the Health Star Rating [51] interpretive nutrition label in New Zealand and Australia, and Traffic Light Labelling [50] in the UK, and Canada’s proposal for mandatory FoP labelling to be applied to foods high in saturated fat and/or sugars and/or sodium [52] should continue to provide consumers with intuitive information to enable healthier food choices and reduce sodium intake.

While many participants in the studies included in this review believed their respective nations were consuming excessive amounts of salt, they also thought their own intake fell within appropriate ranges. There was agreement across all studies with participants reporting a high level of concern about the amount of salt in foods, and placing high importance on reducing dietary intake. Actions to reduce intake such as reducing salt during cooking, using other herbs and spices during cooking and avoiding salty snacks corresponded to the overall belief that responsibility to reduce salt intake lies with the individual (as opposed to government agencies, food manufacturers, and fast food chains) [22, 27, 28, 45].

Previous reviews on KAB related to dietary salt intake have been limited to summarising knowledge related to dietary salt/sodium intake [53], reviewing the tools used to measure KAB outcomes, and exploring gender differences in KAB outcomes [54]. In contrast to these previous studies, a strength of this review is that is it the first to report on all three concepts together, i.e. knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to dietary salt intake. Another strength of this review was the systematic search strategy itself. The search criteria included research completed from 1950 to June 2018, across four literature databases, thereby capturing a larger body of evidence compared with previous reviews, the first of which included studies from only one journal published between 2013 and 2017 [54] and second of which sourced literature from a two databases between 1990 and 2014 [53]. In addition, only studies from high-income countries were included, to enable findings to be summarised based on similar cultures and food supplies.

Nonetheless, a 2014 review by Sarmugam and colleagues which included studies from both high-income and developing countries found similar results to our review with respect to knowledge [53], i.e. participants were unable to identify the correct dietary recommendations, did not know the relationship between salt and sodium or the main food sources of these nutrients, and reported general confusion when interpreting ‘salt’ and ‘sodium’ information on food packaging.

The studies included in this review also had some limitations, meaning it is difficult to determine clear associations between knowledge and attitudes on specific salt-related behaviours or to generalise reported KAB across population sub-groups. First, a number of different tools were used by the studies to measure KAB. This suggests the need for a validated tool. However, as discussed by McKenzie et al. [54], it may be difficult to use the same validated tool to generalise results across different populations due to cultural and social influences on KAB [7, 54]. Second, the self-reported data across all studies raises the concern of social desirability bias, with the potential for consumers to provide responses perceived more socially accepted. Thirdly, as often acknowledged by included studies, findings have limited generalisability due to convenience sampling methods and risk of non-response bias and selection bias due to limited recruitment methods such as consumer panels, and only including those with internet access or landline telephones.

In summary, this review provides sodium reduction advocates and policymakers a concise summary of the current KAB related to dietary salt intake in adults in high-income countries. Several opportunities for improving future research are identified including use of representative samples (i.e., appropriately powered) to assess differences in KAB by sociodemographic sub-groups and assess associations between KAB. Sodium reduction programmes should ensure they incorporate assessment of KAB to monitor changes in KAB over time and ensure sodium reduction awareness campaigns are designed to be responsive to any improvements or changes.

Conclusions

This review identified consumers have low levels of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to dietary salt intake. Therefore, in order to reach the WHO 2025 sodium reduction target, future salt reduction programmes must continue to take a multi-level approach. Greater emphasis of individual KAB is required, and specific initiatives need to focus on educating consumers about the relationship between salt and sodium, recognising commonly consumed high-sodium foods, and label reading to accurately interpret sodium/salt information in food packaging. By doing so, consumers will be adequately informed and empowered to make healthier food choices and reduce individual sodium intake.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

World Health Organisation. Global status report on non-communicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010.

Deckers IAG, van den Brandt PA, van Engeland M, Soetekouw PMMB, Baldewijns MMLL, Goldbohm RA, et al. Long-term dietary sodium, potassium and fluid intake; exploring potential novel risk factors for renal cell cancer in the Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:797–801.

D’Elia L, Rossi G, Ippolito R, Cappuccio FP, Strazzullo P. Habitual salt intake and risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:489–98.

He FJ, Jenner KH, MacGregor GA. WASH-world action on salt and health. Kidney Int. 2010;78:745–53.

World Health Organisation. Guideline sodium intake for adults and children sodium intake for adults and children. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2012.

Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, Ezzati M, et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003733. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003733.

World Health Organisation. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable disease 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2013.

•• World Health Organisation. The SHAKE technical package for salt reduction. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016. Strategy for the design and implementation of sodium reduction programmes.

•• Trieu K, Neal B, Hawkes C, et al. Salt reduction initiatives around the world—a systematic review of progress towards the global target. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130247. Systematic review of the global progress of sodium reduction programmes.

Charlton KE, Langford K, Kaldor J. Innovative and collaborative strategies to reduce population-wide sodium intake. Curr Nutr Rep. 2015;4:279–89.

Charlton K, Webster J, Kowal P. To legislate or not to legislate? A comparison of the UK and South African approaches to the development and implementation of salt reduction programs. Nutrients. 2014;6:3672–95.

Brown IJ, Tzoulaki I, Candeias V, Elliott P. Salt intakes around the world: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:791–813.

Johnson C, Santos JA, McKenzie B, Thout SR, Trieu K, McLean R, et al. The science of salt: a regularly updated systematic review of the implementation of salt reduction interventions (September 2016–February 2017). J Clin Hypertens. 2017;19:928–38.

Webster JL, Dunford EK, Hawkes C, Neal BC. Salt reduction initiatives around the world. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1043–50.

World Health Organisation. WHO Creating an enabling environment for population-based salt reduction strategies: report of a joint technical meeting. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010.

Bettinghaus EP. Health promotion and the knowledge-attitude-behavior continuum. Prev Med. 1986;15:475–91.

Worsley A. Nutrition knowledge and food consumption: can nutrition knowledge change food behaviour? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2002;11:579–85.

Sarmugam R, Worsley A, Flood V. Development and validation of a salt knowledge questionnaire. Public Health Nutr. 2013;17:1061–8.

Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated march 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011.

The World Bank. New country classifications by income level: 2018–2019|the data blog. In: World Bank. 2018. http://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2018-2019. Accessed 13 Jul 2018.

Arcand JA, Mendoza J, Qi Y, Henson S, Lou W, L’Abbe MR. Results of a national survey examining Canadians’ concern, actions, barriers, and support for dietary sodium reduction interventions. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:628–31.

Charlton K, Yeatman H, Houweling F, Guenon S. Urinary sodium excretion, dietary sources of sodium intake and knowledge and practices around salt use in a group of healthy Australian women. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34:356–63.

Claro RM, Linders H, Ricardo CZ, Legetic B, Campbell NRC, Moreira Claro R, et al. Consumer attitudes, knowledge, and behavior related to salt consumption in sentinel countries of the Americas. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2012;32:265–73.

Dewey G, Wickramasekaran RN, Kuo T, Robles B. Does sodium knowledge affect dietary choices and health behaviors? Results from a survey of Los Angeles County residents. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017; https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.170117.

Grimes CA, Riddell LJ, Nowson CA. Consumer knowledge and attitudes to salt intake and labelled salt information. Appetite. 2009;53:189–94.

Grimes CA, Riddell L, Nowson CA. The use of table and cooking salt in a sample of Australian adults. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010;19:256–60.

Grimes CA, Kelley S-J, Stanley S, Bolam B, Webster J, Khokhar D, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to dietary salt among adults in the state of Victoria, Australia 2015. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:532.

Khokhar D, Nowson CA, Grimes CA. Knowledge and attitudes are related to selected salt-specific behaviours among Australian parents. Nutrients. 2018; https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10060720.

Harris R, Rose A, Unwin N. The Barbados national salt study: findings from a health of the nation sub-study 37; 2015.

Kim MK, Lopetcharat K, Gerard PD, Drake MA. Consumer awareness of salt and sodium reduction and sodium labeling. J Food Sci. 2012;77:S307–13.

Kim MK, Lee KG. Consumer awareness and interest toward sodium reduction trends in Korea. J Food Sci. 2014;79:S1416–23.

Land M-A, Webster J, Christoforou A, Johnson C, Trevena H, Hodgins F, et al. The association of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to salt with 24-hour urinary sodium excretion. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(47):47.

Levings JL, Maalouf J, Tong X, Cogswell ME. Reported use and perceived understanding of sodium information on US nutrition labels. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E48.

Marakis G, Tsigarida E, Mila S, Panagiotakos DB. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of greek adults towards salt consumption: a Hellenic food authority project. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1877–93.

Marshall S, Bower JA, Schröder MJA. Consumer understanding of UK salt intake advice. Br Food J. 2007;109:233–45.

Odom EC, Whittick C, Tong X, John KA, Cogswell ME. Changes in consumer attitudes toward broad-based and environment-specific sodium policies-SummerStyles 2012 and 2015. Nutrients. 2017;9:836.

Papadakis S, Pipe AL, Moroz IA, Reid RD, Blanchard CM, Cote DF, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to dietary sodium among 35- to 50-year-old Ontario residents. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:e164–9.

Patel D, Cogswell ME, John K, Creel S, Ayala C. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to sodium intake and reduction among adult consumers in the United States. Am J Health Promot. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.150102-QUAN-650.

Pomerleau J, McKee M, Robertson A, Kadziauskiene K, Abaravicius A, Bartkeviciute R, et al. Dietary beliefs in the Baltic republics. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:217–25.

Regan Á, Shan CL, Wall P, Mcconnon Á. Perspectives of the public on reducing population salt intake in Ireland. Public Health Nutr. 2015;19:1327–35.

Sarmugam R, Worsley A, Wang W. An examination of the mediating role of salt knowledge and beliefs on the relationship between socio-demographic factors and discretionary salt use: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(25):25.

Vitale K, Paradinović S, Durić J, Dika Ž, Jurić D, Luketić P, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice about salt intake in Croatian continental rural population. Agric Conspec Sci. 2012;77:151–6.

Webster JL, Li N, Dunford EK, Nowson CA, Neal BC. Consumer awareness and self-reported behaviours related to salt consumption in Australia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010;19:550–4.

Welsh EM, Perveen G, Clayton P, Hedberg R. Sodium reduction in communities Shawnee County survey 2011: methods and baseline key findings. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20:S9–15.

Wickramasekaran RN, Gase LN, Green G, Wood M, Kuo T. Consumer knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of sodium intake and reduction strategies in Los Angeles County: results of an Internet panel survey (2014-2015). Calif J Health Promot. 2016;14:35–44.

Wyllie A, Moore R, Brown R. Salt consumer survey. 2011.

Land M-A, Webster J, Christoforou A, Praveen D, Jeffery P, Chalmers J, et al. Salt intake assessed by 24 h urinary sodium excretion in a random and opportunistic sample in Australia. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e003720.

Wyness LA, Butriss JL, Stanner SA. Reducing the population’s sodium intake: the UK Food Standards Agency’s salt reduction programme. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:254–61.

McLean R, Hoek J. Sodium and nutrition labelling: a qualitative study exploring New Zealand consumers’ food purchasing behaviours. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1138–46.

FSA. Guide to creating a front of pack (FoP) nutrition label for pre-packed products sold through retail outlets. Food Stand Agency 27; 2013.

Ministry for Primary Industries. The health star rating (HSR) industry kit. 2015.

Government of Canada Food front-of-package nutrition symbol consumer consultation|healthy eating consultations. 2017. https://www.healthyeatingconsultations.ca/front-of-package. Accessed 9 Aug 2018.

Sarmugam R, Worsley A. Current levels of salt knowledge: a review of the literature. Nutrients. 2014;6:5534–59.

Mckenzie B, Santos JA, Trieu K, Thout SR, Johnson C, Arcand JA, et al. The science of salt: a focused review on salt-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviors, and gender differences. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20:850–66.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Neela Bhana, Jennifer Utter, and Helen Eyles declare they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cardiovascular Disease

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bhana, N., Utter, J. & Eyles, H. Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviours Related to Dietary Salt Intake in High-Income Countries: a Systematic Review. Curr Nutr Rep 7, 183–197 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-018-0239-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-018-0239-9