Abstract

The World Health Organization promotes salt reduction as a best-buy strategy to reduce chronic diseases, and member states have agreed to a 30 % reduction target in mean population salt intake by 2025. This systematic literature review identified a number of innovative population-level strategies, including promotion of a substitute for table salt, provision of a salt spoon to lower the amount used in home cooking and social marketing and consumer awareness campaigns on salt and health. In high-income nations, engagement with the food industry to encourage reformulation of processed foods—whether through voluntary or mandatory approaches—is key to salt reduction. Legislation of salt content in foods, although not widely adopted, can create concrete incentives and disincentives to meet targets and does not rely on individuals to change their behaviour. The important role of advocacy and lobbying to change the food supply is undisputed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Salt is a chemical compound made of sodium and chloride that has been an important part of human civilization for thousands of years. Salt’s ability to preserve food helped to eliminate the dependence on the seasonal availability of food and allowed transport of food over long distances, thus facilitating food trade. However, salt was difficult to obtain, and so, it was a highly valued trade item. The invention of refrigeration in 1876 meant that salt was no longer relied upon as a preservative, but its intake, nevertheless, continued to rise. Today, salt is ubiquitous in the food supply because it is a cheap condiment and food ingredient [1].

It is widely accepted that excess sodium, or dietary salt, intake causes blood pressure to rise and that salt consumption is a major determinant of population blood pressure levels [2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that high blood pressure is the third leading cause of disease worldwide [2]. High blood pressure or hypertension accounts for 62 % of strokes and 49 % of coronary heart disease (CHD), and the treatment of raised blood pressure is required to prevent these vascular events [3].

It has been estimated that half of all diseases caused by high blood pressure occur amongst individuals with blood pressure levels below 140/90 mmHg [2]. Such individuals are not typically considered to be at risk of blood pressure-related diseases and are not prescribed blood-pressure-lowering medications [2]. Because of this, an increasing number of countries around the world are adopting population-based salt reduction strategies [4•]. WHO promotes population-level salt reduction as a “best buy” to reduce chronic diseases (i.e. it is both effective and cost-effective) [5], and Member States have agreed to a target of 30 % reduction in mean population salt intake by 2025 [6].

Salt intakes, everywhere, are excessive. The most recent global estimates showed that, in 2010, mean salt intake was around 10 g per person per day [7, 8]. This is around twice the WHO-recommended target of less than 5 g of salt per person per day [9] that is required to reduce the risk of high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease [4•]. The East African Region had the lowest salt intake at just over 5 g of salt per person per day, while the Central East Asia Region had the highest at around 13 g [4•].

Different salt reduction approaches have been trialled, but their effectiveness has not been well described. Country-specific strategies are required to account for different cuisines and cultural practices. For example, in many low-to-middle-income countries, including China, a large proportion of salt intake comes from discretionary sources (salt added to foods at the table or during cooking). In those settings, the use of salt substitutes, accompanied with behavioural interventions, may be appropriate. On the other hand, in most high-income countries, including Australia, UK and USA, the majority of salt comes from processed foods. In those countries, reformulation is required to change the food supply, either through voluntary industry cooperation or through mandatory mechanisms [4•, 10]. Efforts of advocacy groups have contributed to the widespread uptake of salt reduction efforts around the globe. The World Action on Salt and Health (WASH) has members from 80 different countries who work to pressure multinational food companies to reduce the salt content of their products [11].

In the USA, it has been estimated that a regulatory intervention designed to reduce salt intake by 3 g/day would save 194,000 to 392,000 quality-adjusted life-years and $10 to 24 billion in health care costs annually and be more cost-effective than medications to lower BP in all persons with hypertension [12].

While there is little doubt that excessive intakes of salt are harmful to health, the question of whether very low intakes may also be detrimental has not been widely addressed. There is currently fierce debate regarding the optimal recommended intake for salt, as highlighted in recent commentaries on the topic [13, 14]. WHO recommends a maximum population-level target of 5 g per day (2000 mg Na) [9], and this is the value that 38 countries have adopted as their national targets [15••]. In the USA, the most recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on sodium recommendations [16] indicates that their earlier recommendation to lower population-level sodium intakes to below 2300 mg/day [17] is no longer supported by the evidence. Two population-based studies report that risk of both CVD and mortality follows U-shaped curves relative to sodium intake, with risk of mortality and CVD rising both as intakes drop below 3000 mg/day, and as they rise above 7000 mg/day [18, 19]. Similarly, analyses of other prospective datasets, with up to 15-year follow-up, have reported a nearly fourfold increase in cardiovascular mortality as sodium intake decreased from the highest tertile to the lowest and an approximate doubling of CVD events across the same decrease in intake [20]. Observational data is not as persuasive as experimental data in setting clinical and dietary guidelines [21], and the lack of intervention studies of sufficient duration that include hard endpoints (e.g. CVD, stroke, mortality) hampers efforts in this regard.

The Global Burden of Disease 2010 study [22] estimated the mean level of global sodium consumption to be 3950 mg (9.87-g salt) per day. Globally, 1.65 million annual deaths from cardiovascular causes were attributed to sodium intake above the reference level of 2000 mg (5-g salt) per day. These deaths accounted for nearly one of every ten deaths from cardiovascular causes, while four of every five deaths (84.3 %) occurred in low- and middle-income countries, and 40.4 % of attributed deaths were premature (before 70 years of age). Thus, regardless of existing controversy regarding the lower recommended level for salt intake, population intakes are excessive [4•], and thus, salt reduction strategies are essential to lower intakes of populations. In order to identify and evaluate possible options in this regard, a systematic literature review was conducted. The aim of the review was to identify innovative population-level salt reduction strategies that have been adopted around the world.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Articles published in peer-reviewed journals between January 2000 and March 2014 were included in this review. Eligible studies involved strategies or interventions aimed at a population level with the aim of reducing dietary salt intake. Articles addressing protocols for the implementation of a strategy were included, as well as dietary modelling to assess the potential impact of a strategy. Animal studies, reviews, studies not reported in English and studies with small sample sizes (n < 350) were excluded.

Search Strategy

Medline, Scopus, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library were searched using the following keywords: (sodium OR salt) AND (intake OR consumption) AND (reduction OR limit OR restrict) AND (strategies OR policy OR legislat* OR law OR regulat* OR policy OR ban) AND population.

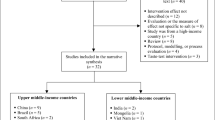

Results

Nine studies were included in the final review, as shown in Fig. 1. The details of each of these studies are summarized in Table 1, and their findings were discussed below, according to three broad topics: salt substitution, behaviour change and advocacy campaigns.

Salt Substitution

Four studies investigated the use of a salt substitute. Bernade-Ortiz et al. (2014) [23] devised a protocol for the implementation of a low-sodium, high-potassium salt substitute in the Tumbes community, Peru, to assess impact on blood pressure over 6 months. The intervention was planned to commence in March 2014, and the results are yet to be published. Li et al. (2007) [24] and Zhou et al. (2013) [25••] carried out double-blinded randomized controlled trials to determine the effects of a salt substitute on blood pressure in Chinese populations. Both studies used the same salt substitute (composed of 65 % sodium chloride, 25 % potassium chloride and 10 % magnesium sulphate). Systolic blood pressure in those with high blood pressure was reduced in both interventions over a 12-month period by a magnitude of 4–5.4 mmHg (Table 1). No change in diastolic blood pressure was observed. Fulgoni et al. (2014) [26] performed dietary modelling to identify the impact of using a salt substitute product, SODA-LO™, in the US food supply. Depending on age, gender and ethnicity, population sodium intake could potentially be reduced by 185 to 323 mg (0.46 to 0.8-g salt) per person per day, if the salt replacement was used to reduce the sodium content of 953 foods by a magnitude of 20–30 %. This represents a relatively small reduction in usual intake of between 6.3 and 8.4 %.

Behaviour Change

Three of the nine identified studies included strategies that encouraged behaviour change to reduce sodium intake at a population level. Land et al. (2014) [27] developed a community-based intervention to mobilize community advocacy efforts and reduce the salt intake of the entire population of Lithgow, a small country town west of Sydney, Australia (population 21,000). The multifaceted 12-month intervention comprised five components: (1) putting salt reduction on the agenda of all health professionals and the local government, (2) community mobilization, (3) advertising the need to reduce sodium intake, (4) education on the importance of reducing salt consumption and practical ways to achieve a reduction and (5) a salt substitute made available to members of the public at no cost. The outcomes of the intervention (i.e. change in 24-h urinary sodium excretion concentrations) have not yet been published. A subsample analysis related to this study reported no clear association between reported knowledge, attitudes and behaviours towards salt and actual salt consumption [28]. This suggests that health education interventions may be of limited efficacy and highlight the need to understand other factors that may prevent consumers from acting on their knowledge and attitudes when it comes to moderating their salt intake.

In contrast to high-income countries, most (76 %) dietary sodium in China is added during cooking [29]. In 2007–2008, the Chinese government sent Beijing citizens a “salt-restriction” spoon which held only 2 g of salt, as a strategy to encourage reduced salt use in cooking. The salt-restriction spoon was designed to help people calculate the amount of salt that they used and adjust measures accordingly to meet recommended targets. For example, a family with four members should eat no more than 24-g salt per day, equal to 12 spoons of salt, which translates into four spoons of salt per meal. However, many people chose not to use the spoon because they found it to be inconvenient and impractical [30], and a 2011 survey found that only 17 % of people were able to use the spoon correctly. Chen et al. (2007) [31••] conducted a randomized controlled trial to test an improved version of the spoon (larger diameter with a longer and curved handle) for its effect on cooking habits, actual salt intake and 24-h urinary sodium excretion over a 6-month period. The improved version of the salt restriction spoon, coupled with health education on the benefits of salt reduction, proved effective at reducing daily salt intake by 1.42 g per day, from 7.65 (SD 4.34) to 6.23 g (SD 3.66) per day.

In New Zealand, McLean et al. (2012) [32] examined how nutrition labels and nutrition claims could influence consumer behaviour at the point of purchase. The addition of a front-of-pack label increased individuals’ ability to distinguish between low- and high-sodium food products. Traffic light-style images (i.e. interpretative front-of-pack labelling) facilitated healthier choices, when compared to either the combination of percentage daily intake thumbnail images on the front-of-pack and mandatory nutrition information panel on the back-of-pack or to the nutrition information panel alone. This study suggests that front-of-pack labelling could be an effective public health intervention to help reduce population-wide sodium intake. However, this study asked consumers to indicate which labelled, fictitious product they would purchase if shopping for that product. Actual behaviours were not measured which is a weakness of the study and limits extrapolation to the real-life situation.

Advocacy Campaigns

Two of the nine studies evaluated advocacy campaigns. In 2007, the Australian Division of World Action on Salt and Health (AWASH) launched a campaign to encourage the Australian government to take action to reduce population salt intake. Webster et al. (2014) [33] evaluated the effectiveness of the campaign on government policy. The campaign was deemed to be successful because it generated intensive media coverage on salt reduction. Importantly, in March 2009, the Food and Health Dialogue initiative was established. The Dialogue brings together representatives from the federal health ministry, the food industry (including the quick service restaurants and supermarket sectors), nongovernmental organizations (National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Public Health Association of Australia), academia and the national food regulator (Food Standards Australia New Zealand). The Dialogue’s primary activity is action on food innovation, including a voluntary reformulation program across a range of commonly consumed foods. This program aims to reduce the sodium, saturated fat, added sugar and total energy content of processed foods across nominated categories, whilst increasing their fibre, wholegrain and fruit and vegetable content. Voluntary reformulation targets were set at levels that recognized technical and safety constraints. The Dialogue’s reformulation program was to be supported by consumer education activities around reducing and standardizing portion sizes and enabling healthier food choices. However, despite highly credible goals, an evaluation of the first 4 years of the Dialogue showed disappointing outcomes [34]. The public-private partnership model resulted in the establishment of targets for only 11 (8.9 %) of a total of 124 possible action areas for food reformulation and portion standardization. Further, none of these targets had been met in that time frame. There was also no evidence that any education programs had been implemented by the Dialogue. It has been suggested that the public-private partnership model proved inadequate as a mechanism by which to achieve food industry action [32].

In the UK, Shankar et al. (2013) evaluated the effectiveness of the Food Standards Agency’s (FSA) famous “Sid the Slug” campaign, launched in 2004 [35•]. The multimedia campaign aimed to raise awareness that salt was bad for health, based on the premise that salt kills slugs and can harm humans too [36]. Social marketing involved advertising billboards, television commercials and internet coverage. Evaluation after this first stage of the campaign revealed that within a year, the proportion of people who knew the dietary target for salt had increased from 3 to 34 % [35•]. The second stage of the FSA awareness campaign focused on behaviour change, including targeted TV advertisements and other materials with the slogan “Is your food full of it?,” encouraging consumers to check food labels and select products with the lowest salt content. Subsequent evaluation of the social marketing campaign has demonstrated an impressive impact in terms of reported changes in consumer behaviour [34].

In terms of impact evaluation, the campaign reported a reduction of about a gram of salt per person per day in 2008 [34]. By 2010, most processed foods available in supermarkets had salt levels that were 20–30 % [36, 37] lower than when the process commenced in 2003. The UK has since reported further reductions in salt intake, totalling around 15 %. This level of reduction is estimated to save approximately 8000 lives annually [38]. Even more recent work on the campaign’s outcome evaluation has demonstrated successful parallel reductions in blood pressure and stroke mortality [14]. While cause and effect cannot be demonstrated, these reductions are highly likely to be due to population-level reductions in salt intake [39, 40].

Discussion

Population-level salt reduction strategies have been widely adopted as a strategy to lower the burden of non communicable diseases (NCDs), particularly hypertension, heart disease and stroke. A systematic review on salt reduction initiatives that was published in the Journal of Hypertension in 2011 identified that 32 countries had salt reduction initiatives in place [10]. The majority of the activity was in Europe (n = 19 countries) and tended to be government-led (n = 26). At that time, most of these countries (n = 27) had set maximum population salt intake targets, ranging from 5 to 8 g/person per day. An update of the review [15••] demonstrated rapid uptake of salt reduction strategies. By 2015, the number of initiatives had more than doubled, to 75 countries, and had been extended to all regions, including Africa. The majority of programs are multifaceted and include industry engagement to reformulate products (n = 61), establishment of sodium content targets for foods (39), consumer education (71), front-of-pack labelling schemes (31), taxation on high-salt foods (3) and interventions in public institutions (54).

Twenty-nine countries have reported an impact in relation to one or more outcome measurements, whether on population salt consumption, salt levels in foods or consumer awareness. There has been a notable move towards legislation on permitted levels of salt in food categories (discussed further below), but these approaches have not yet been evaluated for impact. An exception is Finland, where the 36 % reduction in population salt intake is partially attributed to mandatory warning labels on high-salt foods that have been in place since 1993 and have led to major reformulation of foods [41, 42].

Our current review has identified existing novel and innovative population-level strategies. In high-income countries, dietary salt comes primarily from processed foods and cannot be easily replaced with a salt substitute. However, in low-to-middle-income countries where most dietary salt comes from food cooked in the home, large blood pressure reductions may be achievable with the use of a salt substitute. Although the salt substitutes cost about 50 % more than normal salt, they remain a low-cost commodity and an effective complement to drug therapy for blood pressure control [25••]. Salt substitution was found to be a feasible and successful dietary approach for reducing salt intake in Chinese populations [24, 25••], which could greatly help reduce the estimated 1 million rural Chinese suffering a stroke each year [24]. An ongoing large-scale trial will evaluate the combined effect of health education and access to a salt substitute [43] and, importantly, assess the cost-effectiveness of such a strategy for large parts of China. While replacement of table salt with salt substitutes involves individual behaviour changes, where promoted and subsidized by governments, it could also be considered a population-level strategy.

Little is known about the consumer acceptability of salt substitutes, despite this being a potential barrier that may adversely impact on the sustainability of programs that rely on the use of salt substitutes. An 8-week randomized controlled trial in South Africa that provided free-of-charge, salt-reduced variants of commonly consumed foods, including a commercial salt substitute, to hypertensive patients from disadvantaged backgrounds, reported that those in the intervention group expressed a dislike of the salt substitute [44]. Reports in the literature of partial replacement of salt in food products (mostly bread) have found that potassium-based alternatives are acceptable in terms of taste [45, 46]. However, the consumer acceptability—in terms of taste, price, storage and functionality—of salt substitutes used in cooking and at the table still needs to be determined in countries where this strategy is seriously been considered by governments as an approach to lower total salt intake.

In low-to-middle-income countries, public health campaigns are needed to encourage consumers to use less salt. A salt-restriction spoon that was provided by the Chinese government to Beijing citizens has proven effective at reducing salt used in cooking and resulted in lowered 24-h urinary sodium excretion [31••].

On the other hand, in high-income countries, around 80 % of salt intake can be attributed to salt added by the food industry. It is therefore essential to persuade the food industry to make gradual and sustained reductions in the amount of salt that they add to their food products [11, 23]. While this approach has been well described [15••, 47], there is still debate regarding the most effective way to engage the cooperation of the food industry. Advocacy activities by lobby groups, such as WASH, have been demonstrated to be key in this regard [33, 34], and the experiences of the UK provide the best example of an approach that has worked [4•, 33]. In Australia, a public-private partnership (the Food and Health Dialogue) was formed to encourage healthier reformulation of foods by the food industry. While the efforts of the Food and Health Dialogue have been criticized by some as being slow to result in outcomes [32], there are some reported successes with regard to meeting sodium reduction targets for the first three categories of food, namely breads, ready-to-eat breakfast cereals and processed meats [48]. Sodium levels of 1849 relevant packaged foods significantly declined between 2010 and 2013. The mean sodium level of bread products fell from 454 to 415 mg/100 g (9 % lower, p < 0.001), and the proportion reaching target rose from 42 to 67 % (p < 0.005). The mean sodium content of breakfast cereals also fell substantially, from 316 to 237 mg/100 g (25 % lower, p < 0.001), over the study period. The decline in mean sodium content of bacon/ham/cured meats was lower (8 %; p = 0.001), but the number of products meeting the sodium target increased from 28 to 47 %. Interestingly, declines in mean sodium content did not appreciably differ between companies that did and did not make public commitments to the targets. The evaluation highlighted two important findings. Firstly, for food categories with defined sodium targets, reasonable progress was made by the food industry. Secondly, the large disparities in the pace of sodium reduction between food manufacturers suggest a need for stronger enforcement mechanisms.

Advances in food technology offer promising alternatives to sodium chloride. SODA-LO Salt Microspheres is a salt reduction ingredient that converts standard salt crystals into free-flowing, hollow microspheres that still deliver the same salty taste by maximizing surface area. The use of this technology would moderately increase the price of a product, but the potential health benefits and reduced health care costs are estimated to vastly outweigh the cost of the technology [26]. So far, no countries have introduced legislation or policy regarding the use of such ingredients in place of sodium chloride in specific food products, but this may be an option in future where individual foods are major contributors to total salt intake. Cost-effectiveness studies are required in this regard, perhaps comparing with the impact of taxation of high-salt foods on salt intakes.

Social marketing techniques, combined with nutrition education including food-based dietary guidelines, have been used in a number of countries to assist consumers to make healthier food choices. The use of simple nutrition labels on food products supports the rapid decision-making that typically occurs in the supermarket environment. One observation study in the UK found that consumers spend an average of 29 s per product bought, and 31.8 % of consumers were noted not to have looked at the product in detail [32]. This suggests that consumers rely on habitual behaviours when choosing products, and even knowledgeable consumers may not use nutrition labels when time pressured [32]. Therefore, simple labels which place fewer demands on consumers’ numeracy and background knowledge, such as the traffic light system, have proven more likely to promote healthy food choices [32].

Given this paper’s focus on population-level strategies for dietary salt intake, it is also important to consider the potential contribution of laws and government regulations. While “regulation” is a broad term that may involve many different actors, “law” specifically relates to regulation by government. Law is now a well-established tool of public health [49], and its role in the prevention of diet-related NCDs is receiving increased attention at a global level [50, 51].

The power of legal and regulatory interventions lies in their ability to modify the “mass influences” on population health and the “underlying causes” of disease [52]. Unlike behaviour change and education-based interventions, which act on individuals, laws for the prevention of diet-related NCDs tend to act on corporate or institutional actors. Such laws might, for instance, limit junk food advertising or mandate the disclosure of nutritional information [53].

Laws mandating salt reduction in processed foods are now emerging as an alternative to voluntary or industry-led salt reduction. Thirteen national jurisdictions currently regulate salt in bread and a handful of other foods; e.g. Greece regulates the salt content of bread and processed tomato products [47]. In 2013, South Africa and Argentina became the first jurisdictions to introduce mandatory salt limits across a broad range of commonly consumed, high-salt foods [54]. In both jurisdictions, the laws are only just now being phased in (e.g. the first target date for South Africa is 30 June 2016), and so, no evaluation of the efficacy of these initiatives is available yet. Nevertheless, it is worth commenting on three key ways in which the use of law might, in future, add value to the interventions highlighted in our review.

Law Creates a Level Playing Field Across the Food Industry

Unlike voluntary industry measures, government regulations apply to all industry players. This can be particularly important for achieving a goal like food reformulation, which comes with an initial financial cost to industry. In the absence of a level playing field, “more enlightened and progressive companies” [55] may be penalized for taking on the commercial risk of reformulation. Evidence from Australia demonstrates uneven progress made by manufacturers in the absence of strong regulatory requirements [48]. While a level playing field is achievable without government regulation [56], this requires a high level of industry engagement and motivation and may not be appropriate in all settings. Particularly in low- and middle-income settings, or where the food industry is made up of disparate, smaller players, government regulation can help to ensure that companies who reduce salt in their products do not act alone.

Law Can Create Concrete Incentives and Disincentives to Meet Targets

While industry-led reformulation and labelling schemes often have laudable intentions, they have been criticized in both Australia and the UK for setting weak, unenforceable targets [32, 57]. By contrast, mandatory nutrition labelling is often argued to have a double effect: guiding consumers to make healthier choices, while encouraging companies to reformulate to achieve a better label [58]. Food labelling generally falls under the mandate of regulatory bodies that stipulate formatting and content requirements on food packaging. Currently, many countries mandate the back-of-pack nutrition information panel, but very few mandate front-of-pack or interpretative labelling. Instead, in many countries, the food industry has adopted voluntary front-of-pack labelling. An example of this is “Daily Intake Guide” thumbnail tabs, commonly used on breakfast cereal packaging, that expresses the contribution of a serve of the product to recommended daily nutrient targets (% DI for sodium, for example). This may confuse consumers, as the value is expressed as a proportion of the maximum recommended target and appears concurrently with the nutritional information panel [58]. As with product reformulation, implementation of effective front-of-pack labelling for sodium is likely to benefit from consistent government rules that ensure that all packaged products carry such labels.

Government involvement in setting and enforcing salt reduction goals can also have the advantage of responsiveness: starting from a self- or co-regulatory base, governments can introduce more stringent measures if the industry fails to meet its own targets and timelines [59].

Law Does Not Rely on Individuals to Change Their Behaviour

As highlighted above, in settings where high salt consumption is due to the salt content of processed foods, behaviour change interventions are unlikely to be appropriate. Salt in processed foods is analogous to Geoffrey Rose’s mass influences on population health, i.e. factors over which individuals have little control. Legal interventions can change the underlying conditions in which food choices are made, rather than relying on individuals’ motivation to change [60]. Measures such as taxation (as is being trialled in Hungary and Portugal) or import controls (as has been proposed in Pacific Island countries [61, 62]) on salty foods can help to reduce their availability and affordability. In time, this can also shift population taste preferences and consumption norms.

In conclusion, population-level salt reduction strategies have been widely adopted across the globe in an attempt to lower salt intakes and, thus, lower the burden of cardiovascular disease. The current review identified a number of novel and innovative approaches to salt reduction that include the introduction of a salt substitute in place of table salt in Chinese communities and the provision of a specially adapted salt spoon used for cooking in Beijing province. In high-income countries, engagement with the food industry to reformulate processed foods is the main goal. Signposting and front-of-pack labels enable consumers to make healthier food choices at the point of purchase—but this requires governmental-level support for implementation. Advances in food technology offer promising alternatives to sodium chloride, but cost may currently be prohibitive for widespread use in the food industry.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

He FJ, MacGregor GA. Reducing population salt intake worldwide: from evidence to implementation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;52(5):363–82.

Webster J et al. The development of a national salt reduction strategy for Australia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2009;18(3):303–9.

Strazzullo P, Cairella G, Campanozzi A, Carcea M, Galeone D, Galletti F, et al. Population based strategy for dietary salt intake reduction: Italian initiatives in the European framework. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;22(3):161–6.

Charlton K, Webster J, Kowal P. To legislate or not to legislate? A comparison of the UK and South African approaches to the development and implementation of salt reduction programs. Nutrients. 2014;6(9):3672–95. This paper compares the process of developing salt reduction strategies in the UK, the country that has made the most progress on salt reduction, and South Africa, the first country to pass legislation for salt levels in a range of processed foods. Valuable lessons for other countries are provided.

World Health Organization. From burden to “best buys”: reducing the economic impact of NCDs in low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2011.

World Health Organization. Follow-up to the political declaration of the high-level meeting of the general assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. Available online: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_R10-en.pdf. Accessed 22 June 2015. .

Asaria P, Chisholm D, Mathers C, Ezzati M, Beaglehole R. Chronic disease prevention: health effects and financial costs of strategies to reduce salt intake and control tobacco use. Lancet. 2007;2044–2053:370.

Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, Ezzati M, et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003733.

World Health Organization. Guideline: sodium intake for adults and children. Available online: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/sodium_intake_printversion.pdf. Accessed 22 June 2015.

Webster JL, Dunford EK, Hawkes C, Neal BC. Salt reduction initiatives around the world. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1043–50.

He FJ, Jenner KH, MacGregor GA. WASH—World Action on Salt and Health. Kidney Int. 2010;78(8):745–53.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, Moran A, Lightwood JM, Pletcher MJ, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:590–9.

Anderson CAM JR, Kris-Etherton PM, Miller EA. Commentary on making sense of the science of sodium. Nutr Today. 2015;50(2):66–71.

Heaney RP. Making sense of the science of sodium. Nutr Today. 2015;50(2):63–6.

Trieu K, Neal B, Hawkes C, Dunford E, Campbell N, Rodriguez-Fernandez R, et al. Salt reduction initiatives around the world—a systematic review of progress towards the global target. PLoS ONE 2015; 10(7). Very recent update of the situation of salt reduction strategies adopted by different countries globally.

Institute of Medicine. Sodium intake in populations: assessment of evidence. Washington: National Academies Press; 2013.

Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes: water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Washington: National Academies Press; 2004.

Thomas MC, Forsblom MJ, et al. The association between dietary sodium intake, ESRD, and all-cause mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:861–6.

O’Donnell MJ. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:612–23.

Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Kuznetsova T, Thijs L, European project on genes in hypertension (EPOGH) investigators, et al. Fatal and nonfatal outcomes, incidence of hypertension, and blood pressure changes in relation to urinary sodium excretion. JAMA. 2011;305:1777Y1785.

National Health and Medical Research Council. How to review the evidence: systematic identification and review of the scientific literature. Canberra: NHMRC; 2000.

Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Engell RE, et al. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2014;37(7):624–34.

Bernabe-Ortiz A, et al. Launching a salt substitute to reduce blood pressure at the population level: a cluster randomized stepped wedge trial in Peru. Trials 2014;15(1).

Li N et al. Salt substitution: a low-cost strategy for blood pressure control among rural Chinese. A randomized, controlled trial. J Hypertens. 2007;25(10):2011–8.

Zhou B et al. Long-term effects of salt substitution on blood pressure in a rural north Chinese population. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27(7):427–33. High-quality randomized controlled trial of relatively long duration (2 years) that shows benefit in both hypertensive and normotensive individuals.

Fulgoni VL et al. Sodium intake in US ethnic subgroups and potential impact of a new sodium reduction technology: NHANES dietary modeling. Nutr J. 2014;13:9.

Land MA et al. Protocol for the implementation and evaluation of a community-based intervention seeking to reduce dietary salt intake in Lithgow, Australia. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:7.

Land MA, Webster J, Christoforou A, Johnson C, Trevena H, Hodgins F, et al. The association of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to salt with 24-hour urinary sodium excretion. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):47. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-11-47.

Anderson CA, Appel LJ, Okuda N, Brown IJ, Chan Q, et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: the INTERMAP study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:736–45.

Wenlan D, Weiwei L, Min K, Yuzhong D, Huilai M, et al. Survey on the situation of salt-restriction-spoon using among urban residents in Beijing in 2011. Chin J Prev Med. 2011;10:952–3.

Chen J et al. Salt-restriction-spoon improved the salt intake among residents in China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e78963. A randomized controlled trial that demonstrated the effectiveness of a simple behavioural intervention on reduced salt intake, through changes in food preparation.

McLean R, Hoek J, Hedderley D. Effects of alternative label formats on choice of high- and low-sodium products in a New Zealand population sample. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(5):783–91.

Webster J. Drop the Salt! Assessing the impact of a public health advocacy strategy on Australian government policy on salt. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(1):212–8.

Elliott T, Trevena H, Sacks G, Dunford E, et al. A systematic interim assessment of the Australian government’s food and health dialogue. Med J Aust. 2014;200(2):92–5.

Shankar B, Brambila-Macias J, Traill B, Mazzocchi M, Capacci S. An evaluation of the UK Food Standards Agency’s salt campaign. Health Econ. 2013;22:243–50. One of the few rigorous evaluations of the UK salt reduction strategy that controls for potential influences of changes in food prices, income and education and demographic factors.

Wyness LA, Butriss JL, Stanner SA. Reducing the population’s sodium intake: the UK food standards agency’s salt reduction programme. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:254–61.

Smith-Spangler CM, Juusola JL, Enns EA, Owens DK, Garber AM. Population strategies to decrease sodium intake and the burden of cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:481–7.

Department of Health. Assessment of dietary sodium levels among adults (aged 19–64) in England (2011). Available online: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130402145952/http://transparency.dh.gov.uk/2012/06/21/sodium-levels-among-adults. Accessed 23 June 2015.

He FJ, Pombo-Rodrigues S, Macgregor GA. Salt reduction in England from 2003 to 2011: its relationship to blood pressure, stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004549. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004549.

He FJ, MacGregor GA. A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:363–84.

Pietinen P, Valsta L, Hirvonen T, Sinkko H. Labelling the salt content in foods: a useful tool in reducing sodium intake in Finland. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(4):335–40.

World Health Organization. Mapping salt reduction initiatives in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2013). [cited 2013 29 October]. Available: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/publications/2013/mapping-salt-reductioninitiatives-in-the-who-european-region.

Li N, Yan L, Niu W, Labarthe D, Feng X, Shi J, et al. A large-scale cluster randomized trial to determine the effects of community-based dietary sodium reduction- the China rural health initiative sodium reduction study. Am Heart J. 2013;166(5):815–22.

Charlton KE, Steyn K, Levitt NS, Peer N, Jonathan D, Gogela T, et al. A food-based dietary strategy lowers blood pressure in a low socio-economic setting: a randomised study in South Africa. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(12):1397–406.

Braschi A, Gill L, Naismith DJ. Partial substitution of sodium with potassium in white bread: feasibility and bioavailability. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2009;60(6):507–21.

Charlton KE, MacGregor E, Vorster NH, Levitt NS, Steyn K. Partial replacement of NaCl can be achieved with potassium, magnesium and calcium salts in brown bread. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2007;58(7):508–21.

Webster J et al. Target salt 2025: a global overview of national programs to encourage the food industry to reduce salt in foods. Nutrients. 2014;6(8):3274–87.

Trevena H, Neal B, Dunford E, Wu JH. An evaluation of the effects of the Australian food and health dialogue targets on the sodium content of bread, breakfast cereals and processed meats. Nutrients. 2014;6(9):3802–17.

Gostin LO. Public health law—power, duty, restraint. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2008.

Magnusson RS, Patterson D. The role of law and governance reform in the global response to non-communicable diseases. Glob Health. 2014;10:44.

Burris S, Anderson ED. Legal regulation of health-related behavior: a half-century of public health law research. Ann Rev Law Soc Sci. 2013;9:95–117.

Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14(1):32–8.

Brownell KD et al. Personal responsibility and obesity: a constructive approach to a controversial issue. Health Aff. 2010;29(3):378–86.

Regulations relating to the reduction of sodium in certain foodstuffs and related matters, Regulation No. R. 214 under the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act 1972 (South Africa), 20 March 2013; and Alimentos, Ley 26.905, Consumo de sodio: Valores Máximos, 13 November 2013.

Cappuccio FP et al. Policy options to reduce population salt intake. BMJ. 2011;343:4995.

He F, Brinsden H, MacGregor G. Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: a successful experiment in public health. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28(6):345–52.

Panjwani C, Caraher M. The public health responsibility deal: brokering a deal for public health, but on whose terms? Health Policy. 2014;114:163–73.

Blewett N et al. Labelling logic: review of food labelling law and policy. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2011.

Magnusson R, Reeve B. ‘Steering’ private regulation? A new strategy for reducing population salt intake in Australia. Sydney Law Rev. 2014;36(2):255–89.

Jewell J, Hawkes C, Allen K. Law and obesity prevention: addressing some key questions for the public health community. WCRF International; 2013.

Christoforou A, Snowdon W, Laesango N, Vatucawaqa S, Lamar D, Alam L, et al. Progress on salt reduction in the Pacific Islands: from strategies to action. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;24(5):503–9. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2014.11.023.

Webster J, Snowdon W, Moodie M, Viali S, Schultz J, Bell C. Cost-effectiveness of reducing salt intake in the Pacific Islands: protocol for a before and after intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:107–14.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Karen E. Charlton has received research support through grants from Pork CRC and Nutrafruit Pty Ltd, compensation from Pork CRC for serving as a programme submanager and from Nestlé for participation in a malnutrition advisory board and received a travel grant from Unilever South Africa to participate in the Salt Watch meeting in Johannesburg (2014).

Kelly Langford declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Jenny Kaldor declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cardiovascular Disease

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Charlton, K.E., Langford, K. & Kaldor, J. Innovative and Collaborative Strategies to Reduce Population-Wide Sodium Intake. Curr Nutr Rep 4, 279–289 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-015-0138-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-015-0138-2